JFK was not just resisting war escalation.

He was resisting the creation of a global systems technocracy.

Building the Technocratic Infrastructure

The Rise of Systems Theory and Input-Output Governance

The intellectual origins of modern systems governance trace back to Alexander Bogdanov’s Tektology (1912), a visionary but often overlooked framework for universal organisational science. Bogdanov’s ambition was to model all complex systems—biological, social, political—using a unifying set of principles, foreshadowing the cybernetic thinking that would later dominate mid-twentieth century governance models. In the decades that followed, the RAND Corporation weaponised systems analysis during the Cold War, applying it to logistics, force structure, and strategic planning. RAND’s techniques formalised a method for managing uncertainty and complexity not through human intuition, but through input-output modelling and algorithmic optimisation.

This approach found a natural early laboratory in the corporate world. Ford Motor Company, under Robert McNamara, became a proving ground for the application of rational systems management, where cost-benefit metrics and output forecasting displaced traditional industrial judgment. When McNamara transitioned to the Pentagon in 1961 as Secretary of Defense, he carried these doctrines with him, imposing the Planning-Programming-Budgeting System (PPBS) across the Department of Defense. In doing so, he initiated the first major experiment in governing a vast political institution not through leadership or negotiation, but through the managerial logic of systems theory.

The Intelligence Front: Amory, Schlesinger, and the Subverted ‘Freedom’ Movement

While systems theory took hold in military and industrial circles, parallel moves were underway within the political and intelligence establishment. Robert Amory Jr., Deputy Director of Intelligence at the CIA, spearheaded efforts to embed long-range systems planning within the Agency’s analytical division, shifting its orientation from traditional human intelligence towards predictive modelling and management science. At the same time, Arthur Schlesinger Jr., Kennedy’s close advisor and court historian, championed a technocratic ‘Third Way’ — a project to blend socialist planning methods with liberal democratic rhetoric, masking the gradual drift towards managerial collectivism.

These intellectual currents found their institutional outlets in seemingly benign initiatives. The World Congress for Freedom and Democracy, publicly promoted as a celebration of liberal values, in practice served to redefine ‘freedom’ itself in terms compatible with a technocratic order, subordinating sovereignty to systems coordination. Domestically, the proposed Freedom Academy sought to reshape American civic culture by inculcating loyalty not to constitutional government, but to a system-managed interpretation of ‘democracy’ aligned with long-range planning principles. Together, these efforts formed an ideological vanguard for the coming systems revolution.

The Push for a National Information Center

In 1963, congressional hearings were convened to discuss H.R. 1946, a bill proposing the creation of a National Research Data Processing and Information Retrieval Center. Ostensibly framed as a response to the growing challenges of scientific information management, the project aimed to centralise the collection, indexing, and retrieval of research data under federal supervision, setting the groundwork for a nationalised system of knowledge control.

Among the key testimonies was that of Dr. Derek de Solla Price, who outlined a vision of scientific coordination on an unprecedented scale. Price’s proposals, while couched in the language of efficiency and progress, pointed clearly towards a future in which the flow of scientific information would be regulated, indexed, and prioritised by central authorities — a decisive move towards embedding scientific activity within the machinery of government-led systems management.

Kennedy’s Resistance to Total Systems Control

Kennedy’s Growing Skepticism

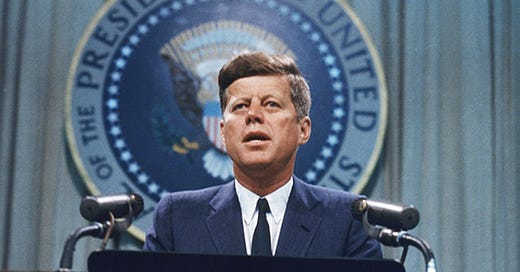

Following the debacle at the Bay of Pigs and the harrowing brinkmanship of the Cuban Missile Crisis, John F. Kennedy internalised a profound lesson: that pure rational-technical decision-making, detached from human judgment and political nuance, could lead not to mastery but to catastrophe. Far from embracing the systems management ethos gaining ground within his own administration, Kennedy grew increasingly sceptical of models, algorithms, and managerial abstractions that failed to account for the unpredictable realities of human affairs.

This scepticism translated into a deliberate emphasis on political leadership grounded in persuasion, negotiation, and moral responsibility, rather than reliance on technocratic tools. When proposals such as the National Research Data Processing and Information Retrieval Center emerged, promising centralised scientific information management, Kennedy approached them with marked caution. He resisted the impulse to consolidate control over knowledge flows, instinctively recognising that centralisation, however rationalised, risked creating new bureaucracies beyond democratic accountability.

Intelligence Wars: Purging the Systems Faction

By 1962–63, Kennedy’s growing distrust of the technocratic faction inside his own intelligence services had crystallised. He moved to dismiss Robert Amory Jr., who had been embedding systems theory and long-range planning into the CIA’s analytical operations. Far from a routine personnel change, Kennedy’s decision was followed by the extraordinary step of authorising the bugging of Amory’s home telephone — a clear indication that the president perceived a deeper threat emanating from within the intelligence bureaucracy. Amory was not merely an analyst; he represented a broader attempt to shift the CIA’s orientation away from traditional espionage and towards predictive, systematised governance.

This conflict brought Kennedy into direct confrontation with Arthur Schlesinger Jr., who sought to shield Amory and protect the broader technocratic network operating through the White House and beyond. Schlesinger’s own proposed CIA reforms were revealing: he advocated for a structural division into operational, administrative, and research branches, with the administrative arm’s decisions subject to State Department approval. Such a framework, far from increasing democratic oversight, risked entrenching a permanent bureaucratic layer—a proto–deep state—beyond effective presidential control. Kennedy’s instinctive resistance to these moves underscores his deeper wariness of ceding sovereignty to systems-managed governance masked by bureaucratic reform.

Motive, Means, Opportunity

Motive — Why Kennedy Had to Go

By 1963, Kennedy had become a significant impediment to the full-scale rollout of the systems-governance model taking root within the American state. He resisted the extension of the Planning-Programming-Budgeting System (PPBS) beyond the Department of Defense, wary of applying mechanical, input-output methodologies to the complexity of civilian governance. His cautious stance towards the proposed National Information Center further demonstrated his reluctance to allow scientific and technical information flows to fall under centralised federal control, a move that would have placed enormous discretionary power in the hands of unelected managers and analysts.

Beyond these domestic considerations, Kennedy’s broader political instincts also ran counter to the emergent technocratic project. He resisted efforts to impose systems-theory frameworks upon social and economic policy, and showed no appetite for the kind of environmental modelling that would later underpin global governance initiatives. His approval of NSAM 263, authorising the drawdown of American forces in Vietnam, posed an even more direct threat: by stepping back from a systems-managed Cold War confrontation, Kennedy disrupted the strategic architecture that systems theorists were preparing to manage on a global scale. His political survival thus became a major obstacle to the full maturation of the managerial technocracy.

Means — Who Was Positioned

The infrastructure for a rapid technocratic consolidation was already in place by the time of Kennedy’s final year. Robert McNamara’s team at the Pentagon, along with McGeorge Bundy and Walt Rostow at the National Security Council, had embedded systems management doctrines deep within the machinery of American governance. Within the intelligence community, key CIA insiders sympathetic to systems theory had begun laying the groundwork for a shift away from traditional espionage towards predictive, model-driven strategic planning. The administrative elite was already primed to escalate the transition the moment political resistance weakened.

Beyond Washington, wider intellectual networks linked through RAND Corporation, Harvard University, and allied foundations stood ready to drive the systems project forward. Figures like Amory and Schlesinger, operating at the intersection of intelligence, academia, and international advocacy, were not merely proposing domestic reform but pushing a broader transnational redefinition of governance itself. Their goal was to soften traditional sovereignty and replace it with a technocratic internationalism—a world managed through rational indicators, scientific metrics, and data modelling, rather than through the unpredictable will of populations and elected leaders.

Opportunity — Dallas and the Administrative Turn

The assassination of John F. Kennedy on 22 November 1963 removed the final human obstacle standing in the way of full technocratic consolidation. In the immediate aftermath, the expansion of systems-driven governance accelerated with extraordinary speed, as if long-prepared plans were simply waiting for the political clearance to proceed. The first civilian drafts for the Planning-Programming-Budgeting System (PPBS) began circulating within federal agencies between late 1963 and early 1964, marking the start of a radical shift from political discretion to input-output managerialism across the civilian government.

Simultaneously, President Lyndon Johnson issued executive orders granting the Federal Reserve unprecedented access to private financial flow data, an essential foundation for high-resolution economic modelling and control. Preparations also quietly commenced for the regional environmental surveillance programmes that would soon evolve into global monitoring frameworks under NATO, UNEP, and SCOPE. In the space of mere months, the cautious, politically-driven governance model that Kennedy had preserved gave way to the unrestrained rollout of systems management across economic, environmental, and social domains.

Aftermath — Systems Consolidation

The PPBS Takeover and National Data Coordination

By 1965, under Lyndon Johnson’s administration, the systems management revolution reached full civilian rollout. LBJ ordered the expansion of the Planning-Programming-Budgeting System (PPBS) beyond the Department of Defense, applying it across virtually every branch of federal government. What had begun as a technocratic tool for military logistics was now imposed upon civilian governance, embedding cost-benefit analysis, target-based metrics, and programmatic modelling into the core processes of policymaking.

Input-output analysis, originally devised to optimise industrial production and military resource allocation, rapidly spread beyond economics into new, highly sensitive domains. Health, education, welfare, environmental management, and urban planning were all restructured around the language and logic of systems theory. The ambition was no longer simply to manage budgets or projects, but to model and govern the entire complex fabric of social life through scientific measurement, predictive indicators, and managerial intervention.

Environmental Systems and the Technocratic Wedge

By 1969, the systems management framework had begun to extend beyond national borders into the environmental sphere. Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s pivotal memorandum to the White House that year explicitly described global environmental monitoring as a ‘natural’ task for NATO — signalling that environmental data collection and regulation were now to be treated as matters of international security and governance. Environmental management, once seen as a domestic concern, was reframed as a transnational systems problem requiring global coordination and surveillance.

This shift rapidly bore institutional fruit. The early 1970s witnessed the creation of major coordinating bodies such as the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), NATO’s Committee on the Challenges of Modern Society (CCMS), and the Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE). These organisations pioneered the use of global indicators — environmental metrics and targets — as tools for monitoring, regulating, and ultimately managing national policies. Environmental treaties increasingly ceased to be mere diplomatic agreements and became instruments of systems control, binding sovereign governments to targets derived from technocratic modelling rather than democratic negotiation.

Systems Convergence: May 23, 1972

The diplomatic thaw between the United States and the Soviet Union under Richard Nixon and Alexei Kosygin opened the door to a new, more subtle form of convergence: the integration of systems governance across ideological lines. The groundwork had already been laid years earlier. In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson ordered the full civilian rollout of the Planning-Programming-Budgeting System (PPBS) across federal agencies, embedding input-output systems management into domestic governance. That same year, Kosygin launched sweeping Soviet economic reforms based on remarkably similar cybernetic principles — an astonishing parallel between Cold War adversaries. NSAM 345, issued in 1966, further signalled a strange, abrupt shift: the United States formally called for ‘forward-looking cooperation’ with the Eastern bloc, a phrase that baffled contemporary observers but perfectly aligned with the quiet systems convergence already underway.

By 23 May 1972, the process reached public fruition when Nixon and Kosygin signed the U.S.–Soviet Agreement on Environmental Cooperation. Although framed modestly, this pact established the formal exchange of environmental data, surveillance technologies, and scientific models across the Iron Curtain. Out of this agreement emerged the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), founded later that year. IIASA rapidly became the core hub for global-scale input-output modelling — covering energy, environment, demographics, and urbanisation — supplying the technical infrastructure for planetary management systems. Beneath the visible détente, a deeper systems-based unification was taking shape: a governance architecture founded not on politics, but on predictive modelling, target indicators, and technocratic necessity.

World Management via Systems Theory

World3, Limits to Growth, and Global Modeling

The publication of the Club of Rome’s Limits to Growth in 1972 marked a decisive inflection point in the ascent of planetary governance through systems modelling. Commissioned by industrialists and technocratic elites, the report employed complex computer simulations to predict the collapse of global civilisation under the pressure of unchecked economic and population growth. Although presented as objective science, Limits to Growth in reality served to frame global challenges in a manner that could only be addressed through technocratic intervention — subtly shifting the conversation away from political negotiation and towards model-driven necessity.

Input-output analysis, once confined to national economies, was now extended to planetary scales. The global economy, energy production, demographic trends, land use, and resource extraction were all subsumed into comprehensive models that claimed predictive power over humanity’s future. In doing so, the Club of Rome provided a blueprint for transnational governance, one where key decisions about the environment, population, and development would increasingly be dictated by system models rather than by democratic processes. Through Limits to Growth, systems theory moved decisively from military and industrial applications into the realm of global social control.

The Global Financial-Environmental Regime

The creation of the Global Environment Facility (GEF) in 1991 provided the financial infrastructure necessary to operationalise planetary systems management. Established under the auspices of the World Bank and linked directly to United Nations initiatives, the GEF was designed to fund large-scale environmental interventions, tying resource flows to compliance with technocratic environmental models. Through the GEF, supranational institutions acquired the means to steer national policies by attaching conditions to financial support, effectively circumventing traditional democratic processes.

The conventions that emerged in parallel — the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) — were both deeply rooted in input-output environmental regulation. They translated ecological processes into measurable indicators and targets, embedding national governance within a framework of continuous surveillance, reporting, and corrective intervention. What appeared as a cooperative international effort to protect the environment was, in practice, the consolidation of a global systems regime — one where nation-states became administrative units within an overarching managerial structure governed by predictive modelling and technocratic enforcement.

Technocratic Systems Today

By the early twenty-first century, the principles of systems governance had evolved into even more sophisticated forms of control. The rise of digital twins — live, real-time simulations of cities, regions, and even entire ecosystems — allowed for the continuous monitoring and predictive management of land use, resource consumption, and human activity. Algorithmic governance, once a theoretical ambition, became an operational reality, with decisions increasingly shaped not by political debate but by predictive analytics and behavioural nudging derived from vast streams of live data.

Social media platforms such as Twitter emerged as critical nodes within this new architecture, functioning as soft systems clearinghouses for the management of mass perception. By monitoring conversations, identifying emergent narratives, and algorithmically amplifying or suppressing particular viewpoints, these platforms enabled real-time steering of public sentiment within tightly controlled parameters. What was once the messy, unpredictable realm of public discourse was quietly transformed into a managed information environment — a live laboratory for social modelling and behavioural adjustment under the guise of open communication.

Conclusion: The Last Stand of Human Politics

The assassination of John F. Kennedy was not merely a rupture in American political life; it marked a civilisational pivot. His removal cleared the path for the quiet replacement of human political governance with the rise of full-spectrum systems management. What followed was not a spontaneous evolution, but the calculated implementation of input–output logic across the economic, environmental, and social realms — a transition from persuasion to programming, from leadership to modelling, from sovereignty to system.

Kennedy had grasped, perhaps uniquely among postwar leaders, the dangers inherent in trusting rational-technical management over the irreducible uncertainties of human judgment. His scepticism towards the National Information Center, his resistance to the civilian expansion of PPBS, his caution over environmental systems control, and his attempt to prevent the CIA’s full technocratic capture all pointed to a deeper political instinct: that the machinery of systems theory, if unchecked, would erode democratic life itself. His death removed the final moral and political brake on the wholesale conversion of governance into a science of managed populations and predictive compliance.

In the decades that followed, the architecture was built in plain sight. Systems management moved from military logistics into education, health, finance, environment, and public discourse. Global treaties disguised as environmental protections embedded nations within supranational indicator regimes. Financial facilities such as the GEF tied money to modelled compliance, while social media emerged as laboratories for the real-time management of mass sentiment. Step by step, the world was reformatted not around the messy realities of human freedom, but around the clean lines of data models and feedback loops.

Unless consciously and deliberately challenged, the systems trajectory inaugurated by Kennedy’s removal will not merely continue — it will culminate in planetary algorithmic management, a form of governance where human sovereignty is reduced to marginalia within a machine-run civilisation. The dream of rational control will have displaced the very essence of politics: judgment, responsibility, and the unpredictable assertion of human will. Kennedy’s ghost haunts this future, a reminder that another course was once possible — and that it may yet be again, if we have the courage to resist the machine.

Richard DeSocio in his book Clash of Dynasties squarely blames Nelson Rockefeller for the assassination of JFK. Donald Gibson in Battling Wall Street showes that Kennedy came into conflict with every single member of the Rockefeller's: David, Nelson, Laurence and J.D. Rockefeller III.

This all ties in with your hypothesis.

Technocracy must be viewed and realised by people that this technocratic future is a major threat to humanity and individual freedom or sovereignty.