Black Tuesday

The Wall Street Crash of 19291 began on October 24th with Black Thursday, a day marked by significant market turmoil. However, on October 29th—Black Tuesday—the markets fully crashed, setting the stage for the ensuing depression.

Coinciding with these events, negotiations that would eventually lead to the creation of the BIS reached a pivotal moment. On that same Black Tuesday, JP Morgan himself sent a notable cable, an act that helped shape the future of global finance.

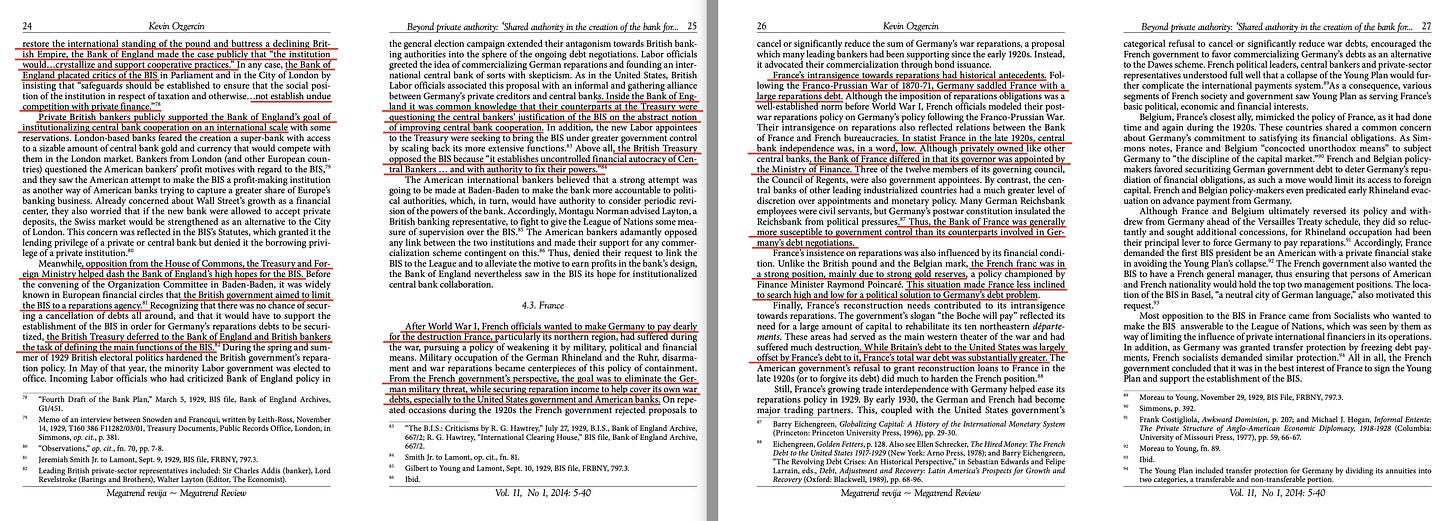

It's a brilliant strategy—if you can engineer it—because it kept long-term global finance planning out of the headlines. In that context, let’s begin with Kevin Ozgercin’s paper2 titled Beyond Private Authority: Shared Authority in the Creation of the Bank for International Settlements. We skip the first pages which set the stage.

It opens by discussing the influence of the private sector during the negotiations, which led to the concept of ‘shared authority’ in the context of German WWI reparations. These were its initial purpose, but central bankers soon considered alternative objectives.

… would lead us to expect that the BIS’s establishment was ultimately explainable from a cost-benefit analysis from the point of view of governments, with private-sector involvement and actions simply being factored in as a cost or benefit from the government actors’ point of view. The evidence shows this approach to be inadequate. By introducing ‘shared authority’ as a concept, it is possible not only to explain why governments complied with private bankers’ normative appeals to take leadership roles in creating the BIS, but also why they believed doing so was right and legitimate.

We're then treated to a brief history of international financial collaboration, which initially operated through private actors such as Rothschild and Morgan, before the Versailles Treaty emerged as a watershed moment in international relations.

Then follows a historical outline which includes the role of the 1922 Genoa Conference, which not only endorsed the gold exchange system but also called for economising the physical movement of gold—the very mechanism that Julius Wolf had outlined in 1892.

But the central bankers also called for a system to adjust imbalances between surplus and deficit countries, along with other mechanisms that eventually emerged at Bretton Woods in 1944, an event which lead to the establishment of the IMF and the World Bank (the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development).

Germany struggled with crippling wartime debts, and if the previous reperations agreement imposed upon Germany at Versailles would ultimately fail, it could well lead to trouble for not only leading creditor banks but also for the victorious nations. But Germany defaulted on its payments in 1923, prompting France and Belgium to occupy the Ruhr district in retaliation. This period was marked by hyperinflation3, which ultimately ended with the introduction of a new German currency, preceding the Dawes Plan of 1924 that primarily deferred the reparation bill. However, as part of that plan, the German government agreed to restructure its central bank under Allied supervision.

While the Dawes Plan initially appeared to work, by the late 1920s progress stalled, leading to calls for renegotiations (via the Young Committee), the securitisation of German debts (packaging these into bonds for market trading), ultimately to lead to a call for an institution, managing German war reparations—the Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

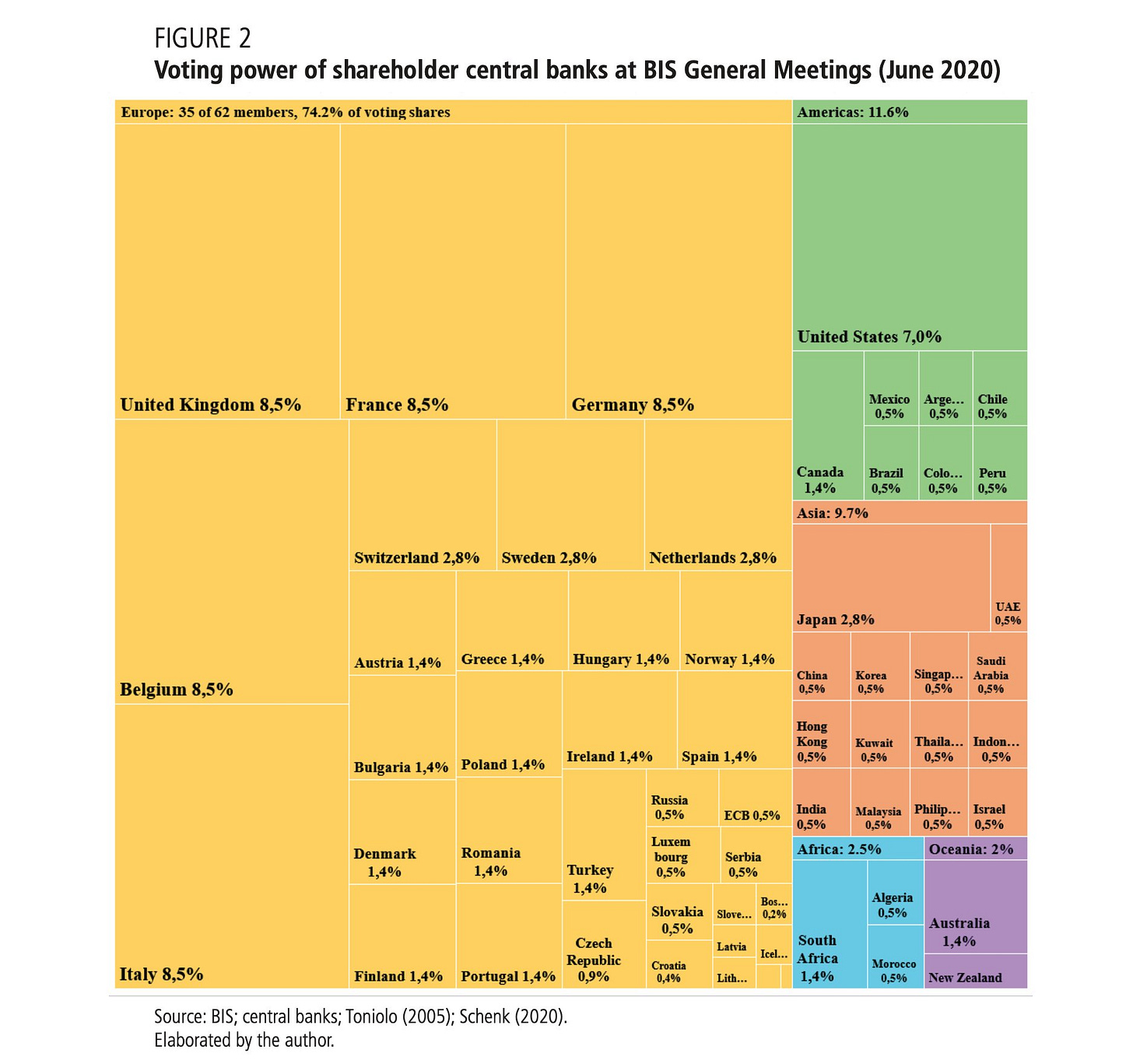

And this is where it becomes interesting: at the time, the seven primary central banks—those of England, Germany, Belgium, France, Italy, the United States, and Japan—were governed in very different ways. In particular, the American and British central banks enjoyed far greater independence than especially the Bank of France. These differences led to divergent views on what the BIS should ultimately become.

Central bankers quickly turned the call into one for the creation of a more substantial institution—a central bank of central banks—while governments remained more muted, favoring a bank strictly focused on handling reparations.

And while you’ve likely heard of the French refusal to renegotiate German wartime debts, you may not be aware of a key reason why—according to Keynes:

If Germany were to pay the whole amount of the reparations due from her under the Dawes scheme, and if the Allies were to use these proceeds to pay what they in their turn owe to the United States under the latest settlements, it would mean that about two-thirds of the proceeds of German reparations would have to be handed on to the United States.

The victorious sides of the First World War were, in fact, as financially strained as Germany and depended on German war reparations to repay their own debts. This dynamic was immediately reiterated throughout subsequent negotiations.

European governments also amassed an enormous amount of private debt during the war,

Under these circumstances, governments became more pliable, leading to broad, if begrudging, support for the BIS. In this regard, the United Kingdom and the United States—both relatively stronger among the warring nations and boasting higher levels of central bank independence—found themselves in an advantageous position.

And American interests wanted the BIS to become an outright, profit-making enterprise.

In fact, their stance was that strong that:

… they were infuriated by the fact that “the chief preoccupation of [their] colleagues seemed to be with a Bank as a Reparations Agency.” The American bankers had grand visions for the BIS, including its ascendance to a position as the leading player in the international bullion market.

Jackson Reynolds, the American banker who served as the lead negotiator in 1929, convened the other central bankers, all of whom aligned with his view on the matter. The BIS was intended to become a for-profit enterprise, although Charles Addis of the Bank of England commented:

… the BIS probably would never have been proposed for establishment “if the reparations settlement had not provided the specific occasion for it.”

In the United Kingdom, however, the debate split between the central bank and the Treasury. The Treasury insisted that the BIS focus solely on German reparations, while the Bank of England, under mounting monetary uncertainty and pressure on the Pound, seized the opportunity to outline a broader mandate for the BIS—albeit in abstract, Aesopian terms.

And as pressure on the Pound mounted, private actors and foreign central banks stepped in to buy British Pounds, effectively countering dwindling gold reserves and thus helping to stabilise the currency—a somewhat fortunate coincidence for the Bank of England, as it transpired.

But the British government was not entirely in agreement. Initially, it wanted the BIS to serve solely as a reparations agency. However, given the circumstances and the realisation that securitizing German reparations was necessary, the Treasury ultimately handed control of the decision to the banking establishment. Nonetheless, suspicions persisted within the Treasury, and the Bank of England was keenly aware of the implications.

France, however, did not face issues related to dwindling gold reserves, but its fiscal position was significantly worse. In retaliation for the excessive wartime reparations imposed by Germany on France in 1871, the French sought revenge. However, with a central bank that was substantially less independent—similar to the position of Belgian central bank—both nations, like Britain, favored the securitization of German reparations. This led to the conclusion that establishing the BIS was ultimately in the French government’s interests.

The Germans, however, suggested using reparations as reserves—a proposal with which the French disagreed. Eventually, Hjalmar Schacht withdrew German support, arguing that the BIS was fundamentally structured against Germany's interests. One argument at the time was that the BIS had little purpose as a center for gold clearing; ultimately, the consensus was that there was no need for the BIS. But immediately before the Young Plan was fully negotiated in 1929, Germany began to experience major fluctuations in its foreign currency reserves—especially during the Paris Conference—leading the German government to believe it was at the mercy of its creditors, which compelled it to sign the agreement.

Yet another fortunate coincidence, it appears.

In March, 1929, JP Morgan cabled Washington:

The great importance of the bank from the American point of view consists…in three things: it secures the color of commercialization [sic] to the German debt....It takes the handling of debts out of political hands and transfers them to the ordinary machinery of finance....it organizes the credit forces of the world for the collection of the debts from Germany in substitution of political and military forces, and therefore makes them much more certain of being paid

However, the securitisation of the German reparations relied heavily upon American investors, which led Morgan to cable Jackson Reynolds:

It is to us i.e. you and J. P. Morgan & Co. that the European Central Banks will look to establish the American participation in the Bank for International Settlements. That being the case it seems to me it would be advantageous for us to agree on what must in substance be the powers and duties of the Bank to enable us to interest the American financial community. The requirement would be in my mind about as follows: (1) the Bank must be a real bank with power to handle its funds either capital or deposits in any manner that the Directors may consider in the interest of the institution; (2) it should be a bank for Central Banks and its accounts should be only with those Banks; (3) when it desires to act in any market through other agents than a Central Bank then it should be only with the approval of the Central Bank of the country involved; (4) its statutes should specifically provide powers to receive the German annuities and to deal with them as directed by the Governments interested; (6) it must not be under Government control except through the heads of the Central Banks; (7) the statutes of the Bank should be so drawn as to leave ample powers to formulate rules and regulations for the convenient conduct of the Bank

And it’s at this stage you realise that this cable was telegraphed on the exact day of Black Tuesday.

Yet another remarkable coincidence, it appears.

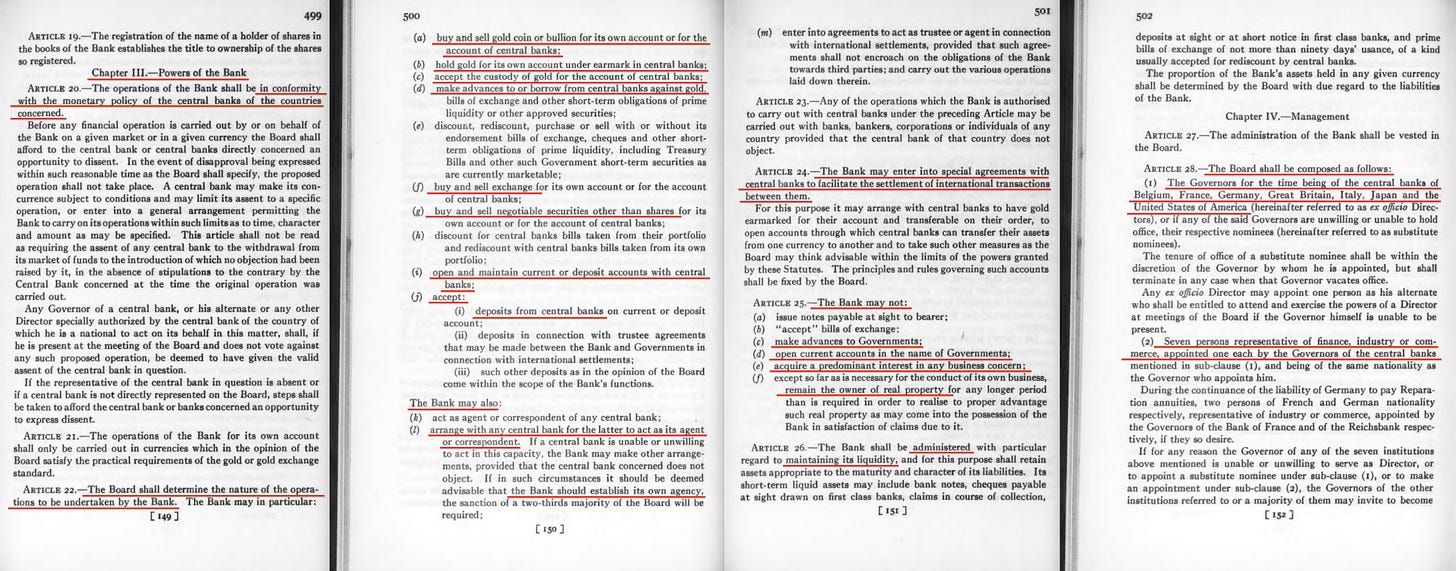

The final revelation in this regard relates to the composition of the board of directors. Each of the seven central banks not only had a seat but also the power to appoint a representative from finance or industry, in addition to the nine representatives—primarily from other member central banks. Consequently, the first board comprised central bankers alongside private industry representatives, establishing a true public–private partnership out of central bank partnerships with governments.

Summary of the above:

Following the First World War, Germany’s war reparations were primarily paid to other European nations, which in turn used these funds to repay their own wartime debts—with the majority of the money ultimately flowing to the United States. Consequently, if Germany had defaulted on its payments, it could have triggered a domino effect, leading other nations to follow suit. This possibility partly explains why the Treaty of Versailles was so onerous. But further, the French attitude was particularly hardened, reflecting a desire for similarly harsh punishment as a response to the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–714 which imposed a such on France.

And though the Dawes Plan in 1924—which primarily relied on debt referrals, but further called for Germany central bank reorganisation under Allied supervision—had temporarily stabilized the German economy, a large part of overall investment was in fact private, aimed at generating a return. As the stock boom accelerated in the late 1920s, this capital left Germany, once again threatening its economy. This dynamic placed American private bankers in a strong position, as a pullback of investment could have caused not just a reversal of fortunes for Germany, but for the rest of the creditor nations as well.

And most European nations were keenly aware that to alleviate this issue, the securitisation of German debts was necessary—which created a call for the establishment of the BIS. This further strengthened the American case, as it would be primarily American investors purchasing these securitised German bonds. Those American interests wanted the BIS to become more than just a bank handling German reparations, but rather a central bank for central banks. Although some of their requests—such as the call for an international currency, which later came to pass through the IMF5—were dismissed, they largely succeeded, and the BIS ultimately became a for-profit enterprise.

The United States and the United Kingdom emerged from the First World War in relatively strengthened positions, with both nations’ central banks enjoying high levels of operational freedom. However, as the United Kingdom began to experience substantial pressure on the pound in the days leading up to pivotal negotiations, the government—despite objecting to a BIS mandate that extended beyond reparations—relied on foreign central banks and private investors to support sterling. Consequently, the Bank of England was empowered to commit to a broader mandate for the BIS, a development which suited American interests. On Black Tuesday, as markets crashed, JP Morgan cabled the American contingent negotiating the Young Plan that the BIS should become a central bank for central banks—free from government control—and that its mandate should be drawn broadly enough to later allow it to formulate its own rules and regulations for conducting business.

Upon its founding, the BIS adopted a structure that more closely resembled a for-profit enterprise than a bank solely focused on reparations. Additionally, the board’s composition is noteworthy: it included 7 directors representing the leading central banks, 7 appointees from private enterprise, and 9 further directors—almost exclusively appointees of other member central banks. This arrangement, within the context of government cooperation, effectively granted the BIS a cooperative, quasi-guild character, mirroring the approach suggested by Julius Wolf in 1892, who through the same book also outlined the gold clearing mechanism that the BIS later adopted.

And though the original mixed board structure—the 7‑7‑9 format—was effectively phased out following the Second World War, this only occurred after Bretton Woods, a conference that transferred key mandates, leaving the BIS to specialize in international clearing, with the gold‑backed dollar serving as the backbone of the international currency system.

And this system remained in place until the late 1960s, when France increased its demand for dollar-to-gold conversions, eventually prompting Nixon to close the gold window in 19716 as part of his… interestingly named ‘New Economic Policy’.

And you’ll find that the Hague Agreement7 of January 20, 1930 makes no mention of a broader mandate for the BIS; all details exclusively relate to its function in handling German reparation payments.

Consequently, the Bank for International Settlements never explicitly received as broad a mandate as was later claimed8. Instead, it was primarily the efforts of American and British interests that led to the system we see today. The framework established during these negotiations allowed the BIS to gradually expand its mandate as it saw fit—all driven by the backdrop of crashing financial markets.

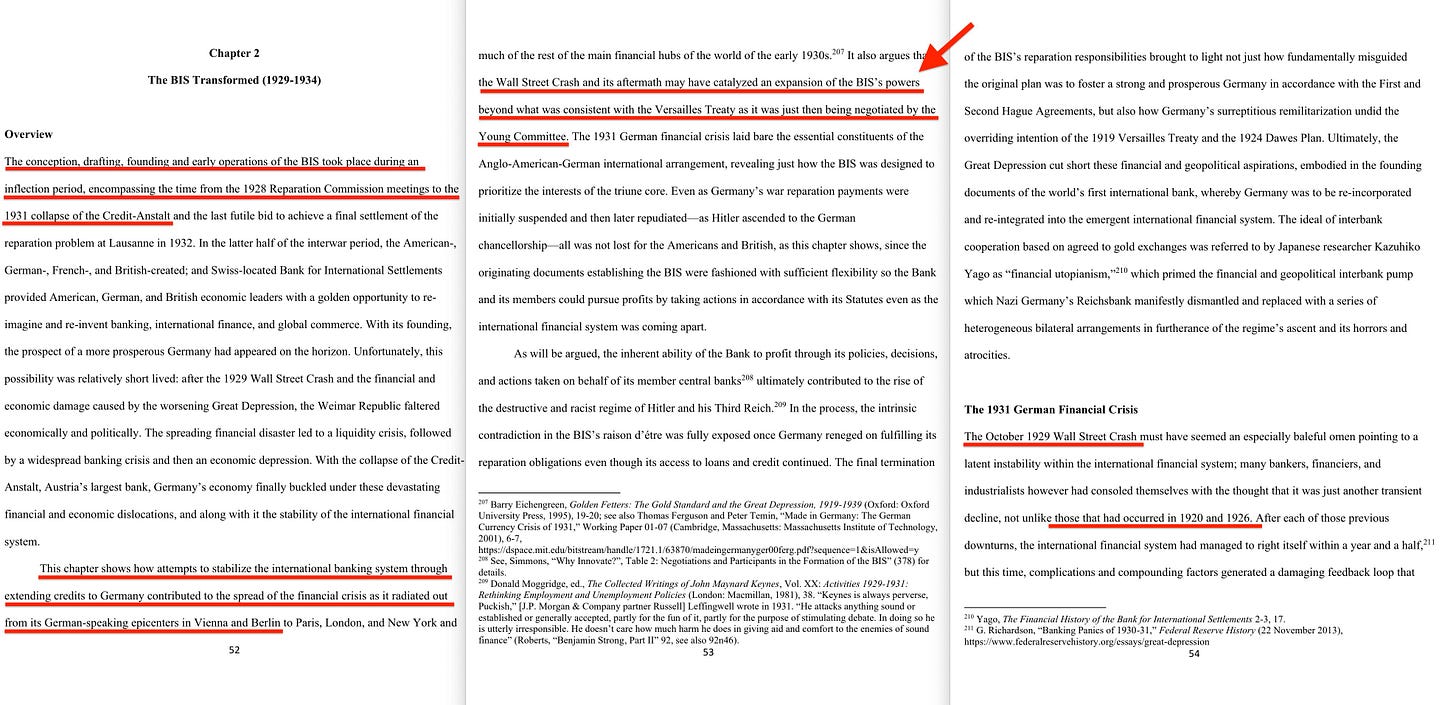

… the Wall Street Crash and its aftermath may have catalyzed an expansion of the BIS’s powers beyond what was consistent with the Versailles Treaty as it was just then being negotiated by the Young Committee

The Banca d’Italia—the Italian central bank—adds further detail to this story9, providing a full list of committee members, a group dominated by banks and large corporations with only a few representatives of the public. In essence, democratic oversight was practically nonexistent. No wonder the central banks got exactly what they wished.

We also see further details reinforcing this narrative, including the central role played by the British and American representatives. They not only chaired all three sub-committees, but also had the Bank of England’s representative, Charles Addis, entrusted with drafting the text:

In this plan 'it is obviously desirable that this institution should be sufficiently broad to permit its activities to extend beyond the field of Germany's obligations, and to provide facilities for international settlements in general

In fact, it sheds further light on the reparations aspect:

This initial American pian of March 1929…; the administration of the payments would be entrusted to a body independent of governments, with central banks merely contributing capital, while management would be vested in representatives of industry and finance.

German reparation taxpayer funds are thus funneled into central banks, which allocate the money to financial institutions of their choosing.

The reparations debt, including even the part represented by deliveries in kind, would be converted into marketable securities by means of an operation that would replace a small number of official creditors (governments) by a host of private holders in a relationship protected from the vicissitudes of relations between states and backed by long-established and exacting commercial ethics.

And this allowed the big banks to profit by floating securitized German reparations and selling them to primarily American private investors.

Ethically.

The Bretton Woods System was established in 194410, at the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference held in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. It’s key features included:

Fixed Exchange Rates: Currencies were pegged to the U.S. dollar, in turn convertible to gold at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce.

International Monetary Fund (IMF): Created to monitor exchange rates and lend reserve currencies to nations with balance of payments deficits.

World Bank (The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development): Established to provide financial and technical assistance to developing countries

And at this very conference, the Bank for International Settlements faced heavy scrutiny for its role in facilitating Nazi Germany’s atrocities. However, when the BIS faced the prospect of closure during these negotiations, Keynes stepped in and vigorously fought to preserve the institution11. A revised mandate ensured its continued existence, and with the loss of both the currency mandate and the role of administering German reparations, the BIS was essentially redefined. It became primarily a forum for central bankers and a clearinghouse for gold-backed USD transactions—which, in turn, backed other leading currencies.

In other words, with the USD acting as an intermediary, the BIS essentially evolved into exactly the institution that Julius Wolf envisioned in 1892.

During the event, Keynes also proposed the idea of an international currency—the bancor12, later introduced in a more limited capacity by the IMF as the Special Drawing Right13—the very concept rejected during BIS negotiations 15 years earlier.

Consequently, central bankers essentially achieved all their objectives, though with powers distributed across several institutions rather than a single one.

The founding of the Bank for International Settlements14 marked the dawn of a new international monetary framework. However, there's a slight issue: the foundational texts the BIS makes available were amended over time. To fully understand the BIS's initial mandate, we need to locate and examine the original statutes.

A first step in our investigation leads us to the October 1930 issue of The Bankers Magazine15, which reveals that Germany’s problems were considered almost unsolvable—and it also raises issues regarding the BIS's mandate:

As the statutes of the Bank for International Settlements determine the scope of that institution only very vaguely, it is often credited with schemes and transactions which are obviously outside its scope as conceived by its authors. Needless to say, reports to that effect prove mostly without foundation.

But there's no need to worry—because as the magazine makes clear, rumors of transactions outside their mandate at this stage are mostly unfounded.

Mostly.

The full statute can be found in the September 1930 issue of International Conciliation16. It begins by clarifying that the seven leading central banks collectively hold a 55% controlling stake in the BIS17. Every expansion of capital allows these controlling banks to maintain their dominant position. In short—those seven banks will never lose their grip on the world’s central bank of central banks unless they choose to do so on their own.

Chapter 3 outlines the powers of the bank, and beyond its emphasis on gold clearing, it makes clear that the issue of German reparations is hardly more than a sidenote for the BIS. The original mandate of the BIS—as established by the Hague Agreement in January 1930—was limited to administering the functions necessary under the New Plan for settling German war reparations. However, once the BIS was established, the community of central bankers expanded its role, effectively disregarding its initial mandate.

Consequently, it was the central bankers themselves who took it upon themselves to broaden their original mandate.

The 1931 BIS annual report18 further demonstrates that not only did the bank implement the gold clearance mechanism outlined by Wolf in 1892, but it also makes clear that the American-driven inclusion of a for-profit motive was endorsed—evidenced by the bank’s high profitability in its first year.

But one question still goes begging—why gold?

Because the gold standard in those days provided a common framework for monetary discipline, credibility, and stability, it created a shared conduit that established commonality among currencies and facilitated the creation of the BIS. Had it not been for this standard, the negotiations leading to the BIS would likely have been so complex that the initiative would have been aborted.

In other words, the gold standard wasn’t just a background detail—it was a key ingredient that underpinned the entire architecture of international monetary cooperation at the time. Without that common anchor, the establishment of the BIS would have been virtually impossible.

The gold standard enabled the founding of the Bank for International Settlements, a bank that strayed far from its original mandate to become the central bank for central banks, exactly as private interests had aimed for during its negotiations.

But almost immediately upon its founding, key central banks severed the gold anchor.