The World Conservation Bank

1977 saw the inaugural World Wilderness Conference1 take place in Johannesburg, South Africa. An interesting choice of location, really, given this being a year of political turmoil, not helped by contemporary partner of former World Bank Director and Club of Rome president, Mamphela Ramphele, was beaten to death by state security.

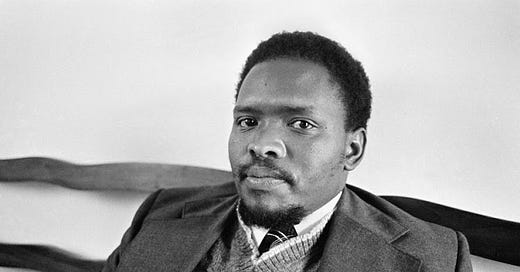

Steve Biko2.

And yes - that really was Mamphela’s former partner - with whom, she had two children… back in the days, where they together both were apartheid activists. And yes - she really was the Club of Rome president up until very recently. Of course, the Club of Rome3 site now describes her as a ‘change agent’, which given that CoR role appears a tad… worrying, really.

But this story isn’t about Mamphela. Or even Biko. In fact, the individual probably closest associated with this particular story is Michael Sweatman. But trouble is - he appears really rather camera shy, given that he’s… pretty hard to track down on an individual level. He did however significantly contribute to the 1987 World Wilderness Congress4, previously covered over here -

In fact, first he’s dragged in by William Burley of the World Resource Institute. Of course, the WRI was setup by James Gustave Speth, who’s frankly as implicated as can be, but let’s set that aside for the time being. Burley challenges the notion that creating (UNESCO Biosphere) reserves are enough. No, those who are in charge of ‘making the real land-use decisions’ are not doing quite enough, besides, all of this needs ramping up on a global scale, and somehow conservation needs linking up with development. Further, he doesn’t actually see a need for land acquisition, because land leases should suffice (which form a part of those Landscape Approach blended finance deals created by the Global Environment Facility).

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The price of freedom is eternal vigilance. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.