In 1906, Arthur Penty published a report on Guild Socialism, proposing that industries be run by worker-owned guilds in the public interest, with public–private cooperation serving a shared objective. In 1914, however, GDH Cole subtly revised the concept — granting experts and civil organisations (such as labour unions) the authority to define that 'common good' at a national, rather than local, level. In practice, Cole’s vision relied on a layer of national planners or committees to determine policy for all.

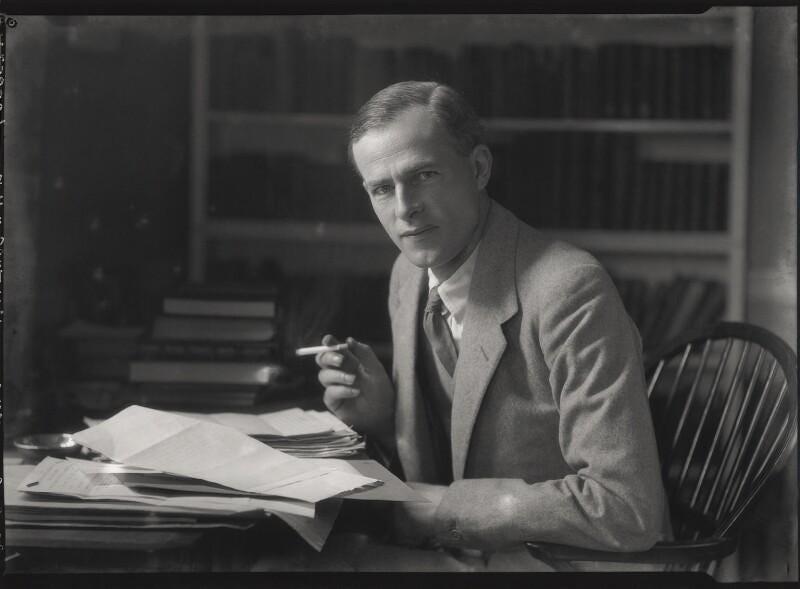

And it was this version that Leonard S. Woolf further expanded in 1916, when the Fabian Society published his report International Government — a document that would go on to serve as the blueprint for the League of Nations.

This is a summary of the recent Substack posts linked below.

Building on these Fabian ideas, Leonard Woolf (Virginia Woolf’s husband) took GDH Cole’s vision global through International Government, arguing that the world needed a permanent international authority. Woolf proposed a network of international agencies — comprised of experts and appointees, not elected representatives — that would set rules across borders for trade, labour, and peace. He insisted these bodies would protect the ‘common welfare’ of humanity, or in other words — policy decisions would be managed above the level of any one nation’s voters — not by a single world dictator, but by many unelected committees coordinating policy worldwide.

And this vision would come to pass through open borders and tariff-free trade, as such arrangements — by necessity — erode cross-border differences in economic legislation. Policies of this kind are, in contemporary terms, often described as neoliberalism — the kind that suddenly gained widespread popularity in the 1990s.

Woolf’s blueprint quickly influenced post–World War I planners. In 1919, at Versailles, Alfred Zimmern and other liberal internationalists wove these ideas into the League of Nations — the first attempt at world government, at least on paper — with powers to settle disputes and oversee mandates. Alongside its creation came new international bodies such as the International Labour Office (ILO) and the International Research Council (later to become the ICSU); two organisations operating entirely outside national oversight, yet quietly siphoning powers away from sovereign states — precisely as Woolf proposed in 1916.

Voting in the League Assembly was indirect — each country represented by its diplomats, not its citizens — and much of the League’s work was carried out by committees of experts (such as the ILO and the IRC) and its secretariat. Though sold as a ‘law of nations’ for peace, it relied on top-down rulemaking and soft agreements — not popular consent.

At the same time, a different hybrid model emerged in communist Russia. Lenin’s New Economic Policy (NEP) of 1921 marked a pragmatic retreat from war communism, reintroducing markets and small-scale private trade — but always under the watchful eye of the Communist Party. Factories and key resources were nationalised, while farmers and merchants were permitted to operate privately — so long as they adhered to party plans and kept their profits modest. The NEP thus revealed an early model for fusing state control with private enterprise under communism — a model that would quietly resurface in new forms internationally after World War II.

The United Nations, founded in 1945, was built on the same underlying logic. The UN Charter explicitly invites ‘social and economic’ groups to advise the world body, and by the 1950s and 60s, this was formalised through a system of ‘consultative status’ for international NGOs — allowing organisations like the Red Cross, trade unions, and business associations to attend conferences and influence official reports. Other bodies, such as IIAS, ICSU, and the IUCN, were granted more direct access, often through quasi-fusions facilitated by UNESCO.

Suddenly, international summits on health, labour, development, and human rights included not only diplomats, but also private foundation fronts and advocacy organisations — an arrangement that effectively merged public policy with private interest through third parties purporting to represent a societal objective. The rhetoric focused on inclusion and expertise — but in reality, unelected NGOs were now helping to draft key documents.

In other words, another NEP-style fusion was unfolding — but this time mediated by Civil Society Organisations rather than the Communist Party, and all under the veneer of Western democracy.

By the 1970s, the model evolved to explicitly include a ‘third sector’. Analysts began describing the world as composed of three primary interest groups: the public sector (elected politicians representing labour), the private sector (enterprise representing capital), and Civil Society Organisations — a category encompassing NGOs, community groups, church networks, and foundation fronts — officially cast as mediators between states and markets. These entities were framed as giving people a voice without the need to overthrow governments or disrupt economies. It was sold as a harmonious solution: let citizens around the world form non-profits and NGOs, and involve them in solving global problems, they said. On the surface, it sounded reasonable, and it looked like decentralisation and democracy in action.

In practice, however, this Third System was often little more than a veneer. Many of these NGOs and CSOs were either formed or heavily funded by international foundations, governments, or multinational corporations. These would join UN committees or summits as ‘stakeholders’, supposedly providing a form of grassroots input — but in reality, they typically supported the same ideas worked out behind closed doors by their elite funders. Policies on trade, health, and the environment were largely pre-agreed in bureaucratic meetings, with civil society organisations employed to feign grassroots support. These NGOs helped frame top-down, expert-driven plans as if they were the result of popular participation, thus recasting centralised, technocratic planning as grassroots campaigning.

In the 1990s, the concept of blended governance gained traction in politics. Tony Blair in Britain and others championed a ‘Third Way’ — a supposed cooperation between market and state actors, where official policy was executed through networks of government agencies, QUANGOs, businesses, charities, and community groups, all working together ‘for the common good’. Schools, hospitals, and urban redevelopment projects were touted as being organised not just by Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) representing the common man, but also by public officials and private enterprise.

However, when CSOs are funded by the same corporate interests they claim to counterbalance, the result is the sidelining of elected politicians. As policy is shaped within trilateral boards, electoral accountability erodes — citizens have no vote over corporate or NGO board members. Decisions once subject to public oversight — budgets, priorities, reforms — are increasingly made behind closed doors, in private conferences and advisory panels, and not at the ballot box.

In short, the Third Way extended the old Fabian model proposed by Woolf: it masqueraded as pragmatic partnership, but in reality, it embedded decision-making in an unelected consensus.

But the UN itself took this model even further. In 1997, Kofi Annan initiated a series of institutional reforms, culminating in 1998 with the granting of General Consultative Status to NGOs — effectively giving them access to all parts of the UN system. Then, in 2000, Wolfgang Reinicke formalised this structure through Critical Choices, in which he urged the UN to rely on ‘global public policy networks’ — trisectoral networks; alliances officially linking states, businesses, and NGOs to address global issues ranging from the environment to labour, all under the banner of the ‘common good’.

In practice, this meant the UN outsourced legislative initiative to international NGOs, many of which had the power to ‘place items on the agenda’. Organisations like the IUCN, World Wildlife Fund, Amnesty International, and major trade associations gained direct access to the drafting of UN agreements — including those related to human rights, development, environmental regulation, and trade. As a result, policy was increasingly shaped not by elected representatives, but by NGOs operating entirely outside the bounds of democratic accountability.

But these developments have deeper roots. Leonard S. Woolf’s vision of international expert rule echoes Eduard Bernstein’s evolutionary socialism from 1899 — a Fabian-style revision of Marxism that proposed socialism could advance not through revolution, but through gradual reform and democratic institutions. Bernstein accepted much of capitalism but sought to domesticate it through legislation and cooperative management in service of the common good.

Bernstein, in turn, adapted the core of this vision from Julius Wolf, who in 1892 outlined a public–private trade framework centred on an international gold-clearing facility — a concept later institutionalised with the founding of the Bank for International Settlements in 1930. Wolf envisioned a mechanism for mediating cooperation between labour and capital on a global scale; Bernstein extended this with a moral veneer, embedding it within a cooperative ethos; and Woolf translated it into the political sphere of international governance, which Alfred Zimmern helped implement through the League of Nations in 1919.

Thus, the intellectual genealogy traces back to Julius Wolf’s ideas. It was his proposals on cooperation and international finance that led to Bernstein’s revisionist Marxist model, which in turn found voice in Woolf’s blueprint for global governance integrated within the League of Nations, and eventually in the United Nations today.

Step by step, voters have watched their influence drain upward — yet no one has explained how, or why. First it was guilds answering to local councils through Penty, then national planners through Cole, followed by states deferring to League bureaucrats through Woolf, and now even governments and NGOs take direction from international networks shaped by figures like Wolfgang Reinicke. Each stage was justified with the same reassuring language: decentralisation, inclusion, participation, consensus — and above all, the common good.

But in practice, these promises concealed a central truth: real power has consistently shifted upward to unelected bodies. Instead of clear laws passed by parliaments, we are given ‘soft law’ — guidelines, recommendations, and standards drafted by regional committees. Instead of ballots, we’re left with ‘inclusive stakeholder consultations’ and ‘participatory partnerships’, where someone you’ve never heard of decides who is allowed to have their voice heard.

In the end, claims of decentralisation turn out to be the exact opposite — a cover for the entrenchment of a global managerial class. Beneath slogans of compassion and care, policy is increasingly managed by experts. The average citizen scarcely notices when decisions migrate from their city council to a UN task force or an NGO consortium — because no one ever tells him that it’s happened. It’s as though the people gradually outsourced their votes to technocrats — without ever being given a vote on the matter.

Each new reform boasts of including ‘voices from the ground’, but those voices are often preselected — foundations chosen to represent entrenched interests. Little by little, elections matter less, while the man in the nice suit on TV tells you how important it is to protect our democracy.

And none of this happened through a single dramatic coup, but through countless conferences, networks, and policies developed off-stage.

At every turn, this was sold as giving the people a voice — while the Civil Society Organisations involved were hand-picked by representatives of the very foundations that funded them, and certainly not in pursuit of the common good of the people. Far from empowering the masses, these organisations functioned as conduits for elite agendas, ensuring that those who paid the bills retained control. The promised ‘participation’ was merely a veneer — a stage-managed performance in which only selected voices were allowed to speak, while real decisions increasingly shifted into the hands of unelected, unaccountable technocrats and corporate interests.

There’s no harm in public labour and private capital cooperating in the public interest. But that objective should be defined democratically — at the ballot box — and certainly not by foundations masquerading as Civil Society Organisations or international NGOs, claiming to act for the common good.