The Third System

With the operational aspects detailed through the post on D(eception)-Day, let’s now take a look at the administrative arrangements. And, look—it’s the same model, again. It’s the public-private-partnership, working for the common good.

The only question is—who defines the common good?

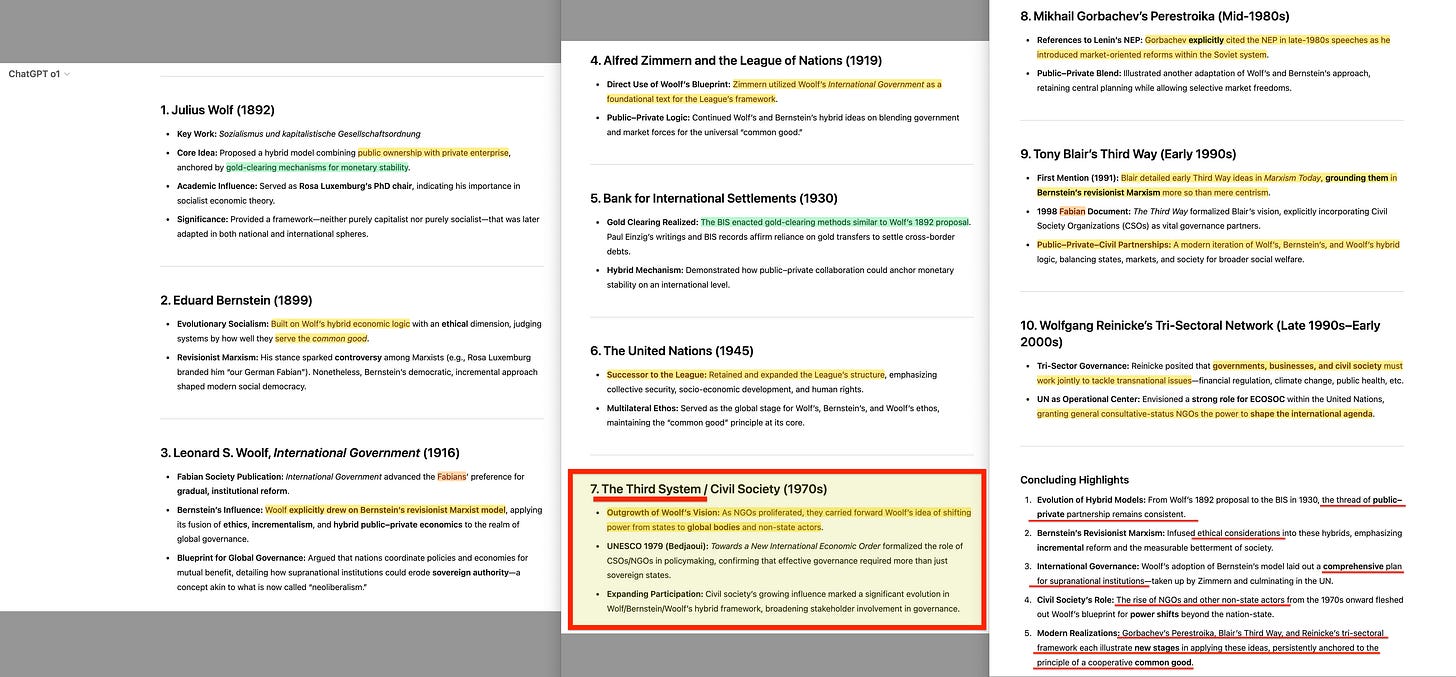

It’s always the same model. Always. Wolfgang Reinicke called it the Trisectoral Network when he implemented it at the United Nations in 2000. Tony Blair’s Third Way followed the same principle in 1998. Glasnost and Perestroika in 1985? Same model. Lenin’s New Economic Policy in 1921? Same again—as with Deng Xiaoping’s reforms in 1978. Same model, same structure, same mechanism. Leonard S. Woolf laid it out through the Fabian Society’s International Government in 1916, which became the blueprint for the League of Nations in 1919—the same institutional architecture later repurposed for the founding of the United Nations. Step further back, and you’ll find Woolf was inspired by Eduard Bernstein’s 1899 work, which itself drew from Julius Wolf’s 1892 publication.

It is always the same model.

So why another post on this topic—especially if we’ve already discussed it, repeatedly?

Simple: the timeline is broken in two. We’ve mostly covered the period from Julius Wolf to the founding of the United Nations, and then again from Gorbachev to Reinicke. This article connects those two timelines—and even better, it does so by explicitly slotting in the Club of Rome, Systems Analysis, environmental narratives, the propaganda emphasis… In fact, of all the pieces of the puzzle, this one appears to tie together a remarkable number of threads. But before we dive into the primary documents, let’s have o1 briefly outline how this model evolved.

Let’s begin with the clincher—the absolutely undeniable.

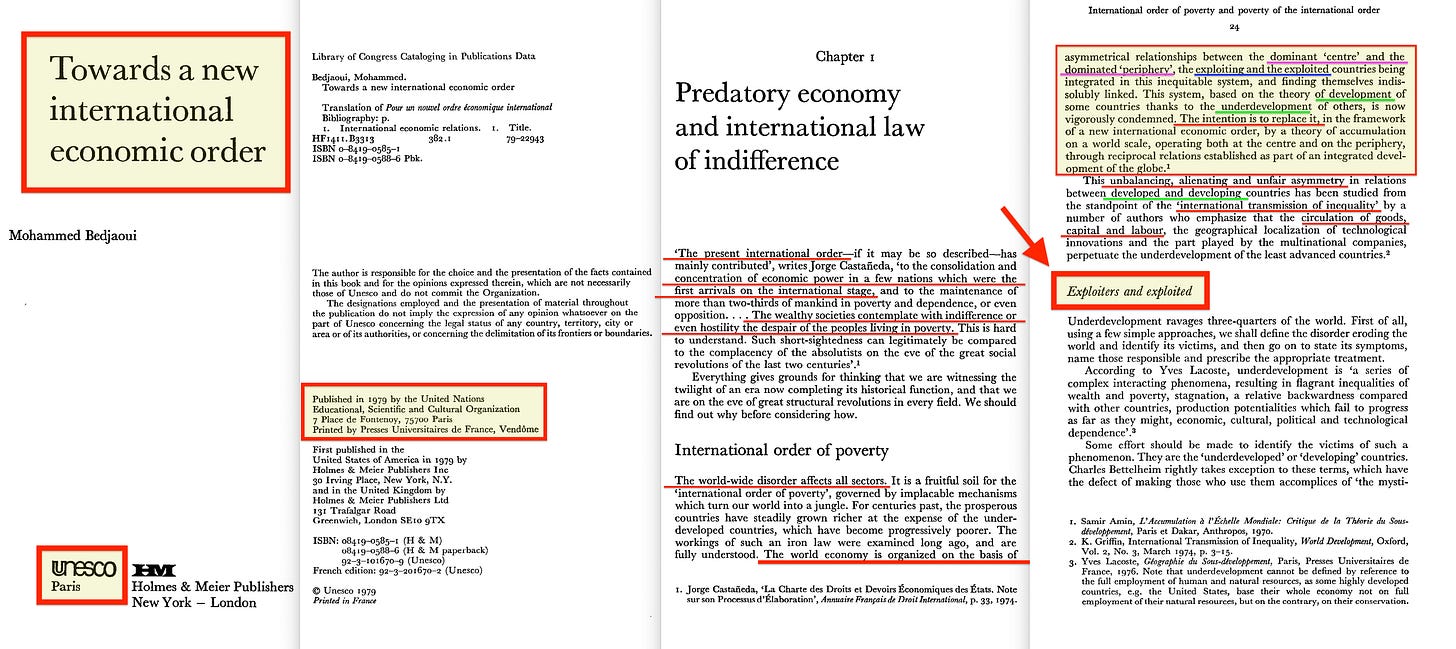

Towards a New International Economic Order by Mohammed Bedjaoui, published by UNESCO in 1979, wastes no time establishing the framework: exploiter versus exploited1.

There’s little point dwelling on the first chapter. It’s pure Frankfurt School Critical Theory trash—oppressor versus oppressed2—repeated relentlessly, line after line.

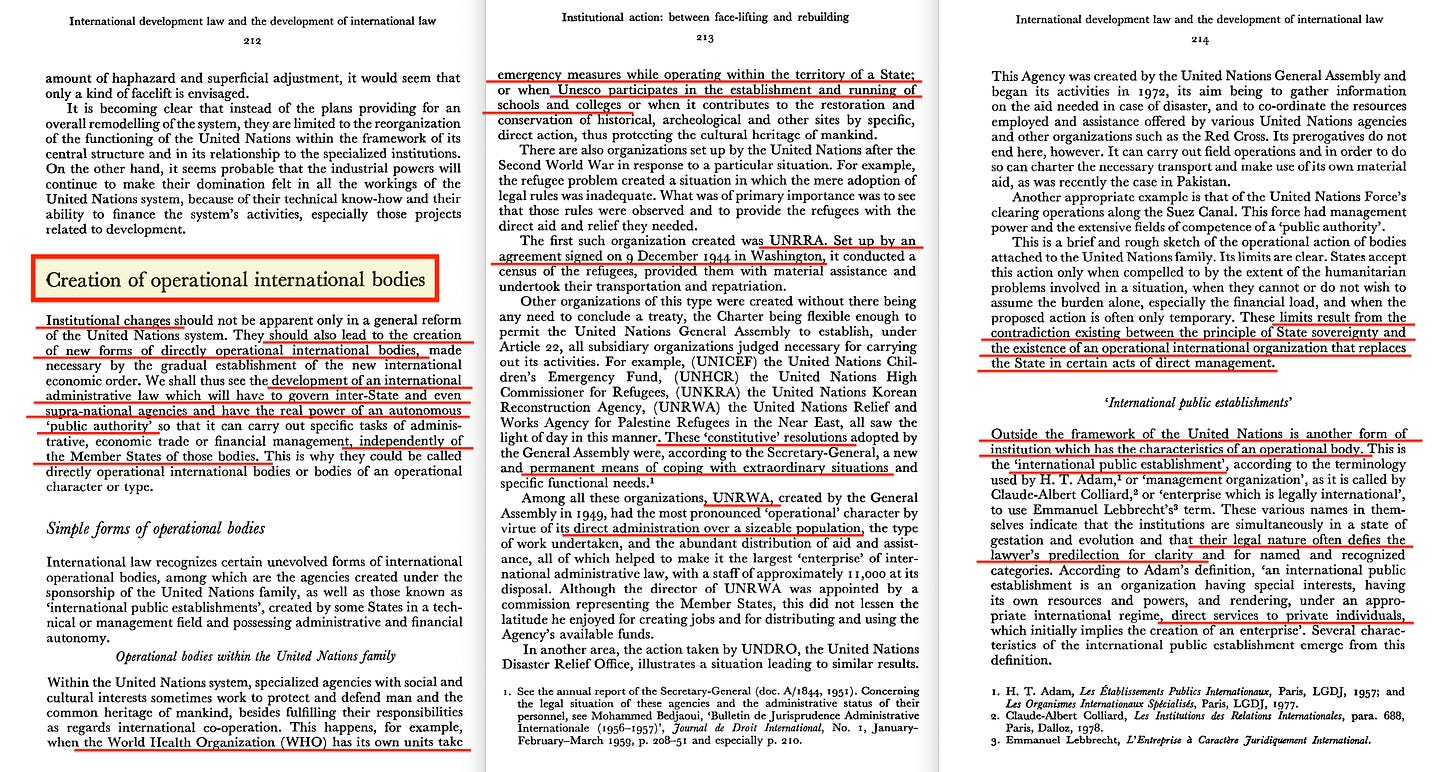

Instead, let’s zip ahead to page 212—’Creation of Operational International Bodies’.

This section lays out how reforming the United Nations system should lead to the creation of new, directly operational international bodies. And in case you don’t speak Aesopian, allow me to translate:

‘Directly operational’ means these bodies would have the legal authority to act on their own—independent of sovereign states. And because they’re international, there’s no democratic accountability involved.

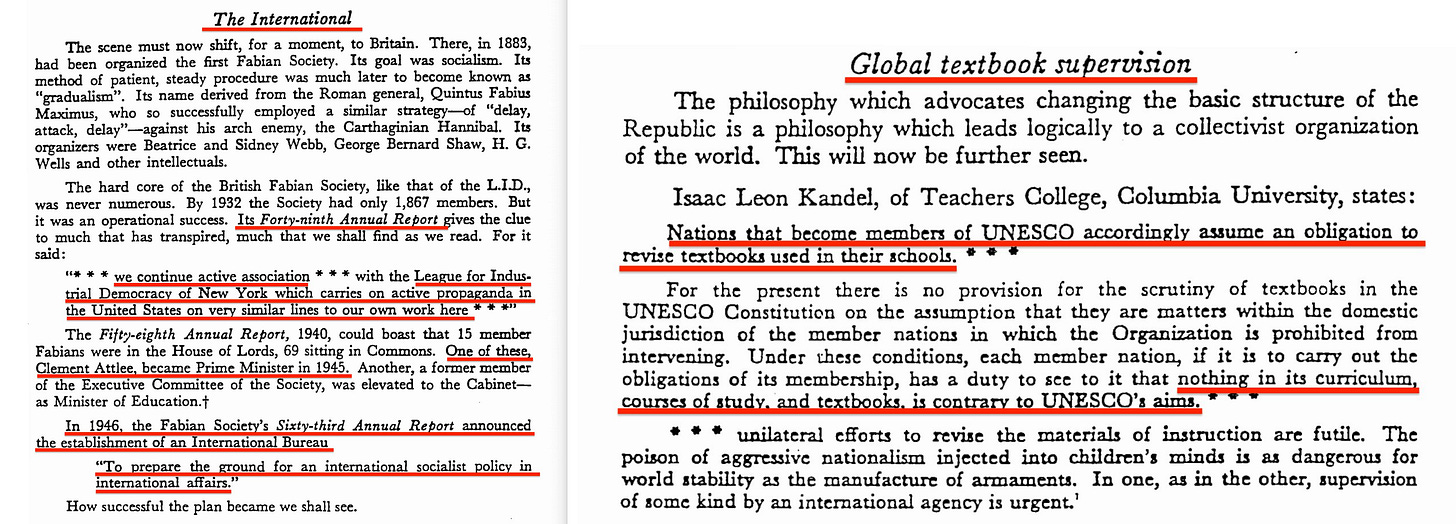

A few examples are given. UNESCO, for instance, retains the right to modify the educational material of member nations3, while the WHO... you catch the drift.

Either way, the issue is that these organisations—with a range of other examples given—are typically limited to acting under specific conditions: alleged health emergencies, for instance, or when explicitly called upon.

However, outside the formal United Nations framework, a new type of organisation is introduced—one that even lawyers struggle to define with clarity: the international public establishment. This model operates differently. It provides services directly to the people, effectively bypassing state authority altogether.

Obligatory joke follows—what do you call 500 international public establishment lawyers at the bottom of the sea? A good start.

But we soon learn that 500 is far too low a number.

Let’s begin by setting the stage:

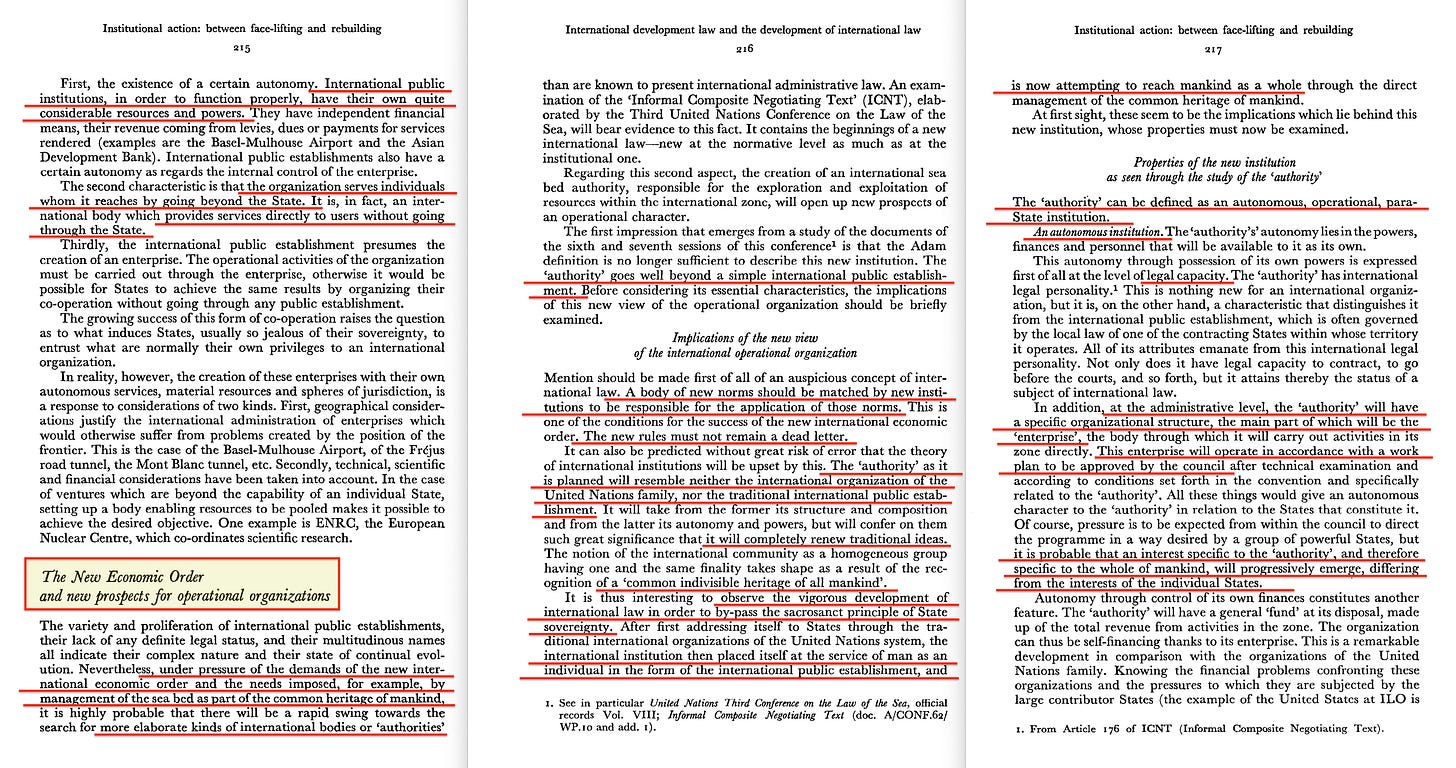

Mention should be made first of all of an auspicious concept of international law. A body of new norms should be matched by new institutions to be responsible for the application of those norms. This is one of the conditions for the success of the new international economic order. The new rules must not remain a dead letter.

See? What they’re seeking is new norms, matched by new institutions—created specifically to draft new norms and ensure their application. But it gets better:

It can also be predicted without great risk of error that the theory of international institutions will be upset by this. The ‘authority’ as it is planned will resemble neither the international organization of the United Nations family, nor the traditional international public establishment.

Wait—so it won’t resemble either?

It will take from the former its structure and composition and from the latter its autonomy and powers, but will confer on them such great significance that it will completely renew traditional ideas. The notion of the international community as a homogeneous group having one and the same finality takes shape as a result of the recognition of a ‘common indivisible heritage of all mankind’.

Ah, there it is. It will resemble an NGO—but one claiming to deliver services directly to the people, bypassing the nation-state entirely. And this, we are assured, will usher in utopia. But for those who still think this isn’t ironclad:

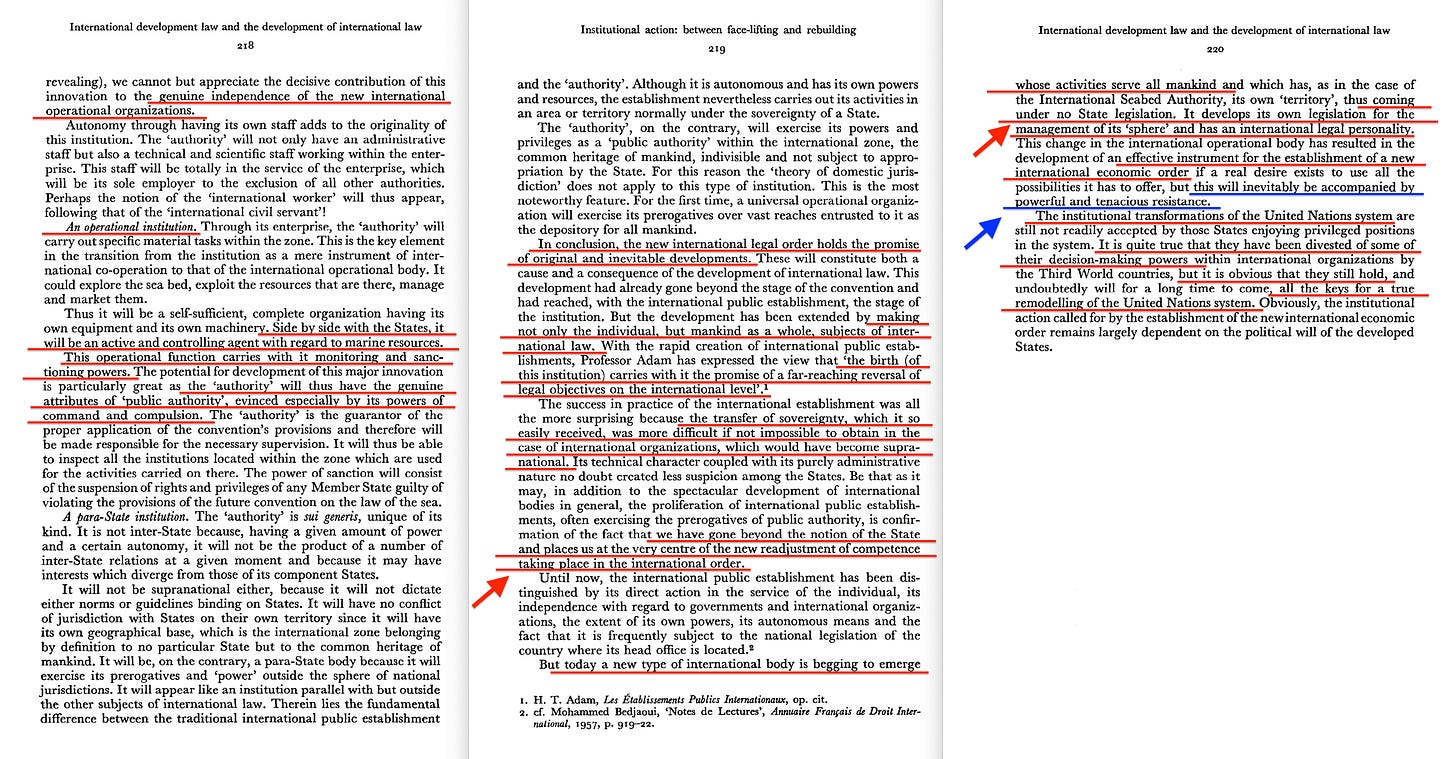

It is thus interesting to observe the vigorous development of international law in order to by-pass the sacrosanct principle of State sovereignty. After first addressing itself to States through the traditional international organizations of the United Nations system, the international institution then placed itself at the service of man as an individual in the form of the international public establishment, and is now attempting to reach mankind as a whole through the direct management of the common heritage of mankind,

Aww, how kind. Altruistic, even. They’re intentionally circumventing national sovereign rights—to protect us, of course.

And then we’re treated to a somewhat familiar pattern:

In addition, at the administrative level, the ‘authority’ will have a specific organizational structure, the main part of which will be the ‘enterprise’, the body through which it will carry out activities in its zone directly. This enterprise will operate in accordance with a work plan to be approved by the council after technical examination and according to conditions set forth in the convention and specifically related to the ‘authority’.

We discussed this principle just the other day. What’s described here is the exact same administrative–operational split that Arthur Schlesinger under Kennedy in 1961 introduced in the context of the CIA—with the State Department being handed administrative control.

And finally—just to make absolutely sure you understand they’re doing all of this for your benefit:

… an interest specific to the ‘authority’, and therefore specific to the whole of mankind, will progressively emerge, differing from the interests of the individual States.

In other words—nation-state sovereignty goes bye-bye.

Anyway, to ensure utopia, these organisations must, quite simply, be completely independent of member states. Sure, states can subscribe—but really, all that does is secure them a front-row seat to the raping and pillaging of whichever nations they happen to dislike—such as their own, given enough time.

Anyway, I’m sure my cynicism is dialled up way too high here:

This operational function carries with it monitoring and sanctioning powers. The potential for development of this major innovation is particularly great as the ‘authority’ will thus have the genuine attributes of ‘public authority’, evinced especially by its powers of command and compulsion.

Then again, perhaps not—especially as these bodies even appear to have the right to run surveillance. And on a global scale, and in the context of the mid-70s that becomes… well, GEMS?

Either way, let’s wrap up this document—because how could it possibly get worse but an organisation outside democratic capacity, which runs surveillance, writes legislation, and enforces it—globally?

But today a new type of international body is begging to emerge whose activities serve all mankind and which has, as in the case of the International Seabed Authority, its own ‘territory’, thus coming under no State legislation. It develops its own legislation for the management of its ‘sphere’ and has an international legal personality. This change in the international operational body has resulted in the development of an effective instrument for the establishment of a new international economic order if a real desire exists to use all the possibilities it has to offer, but this will inevitably be accompanied by powerful and tenacious resistance.

Ah right—by casually acknowledging that people might be less than thrilled about this blatant subversion of sovereignty.

There are a number of documents that go critically underreported—and two of these, in particular, essentially function as a pair. It’s a strategy we see repeatedly: the first presents the conceptual idea, the second delivers the practical implementation. This is a framework the United Nations itself frequently employs.

Take the UNFCCC, for instance—where the 1992 agreement is, at its core, a vague and wishy-washy declaration about climate. The real ‘bite’ didn’t arrive until the Kyoto Protocol in 1997. And while the 2009 Copenhagen Accord is often labelled a failure, it certainly wasn’t—and the 2015 Paris Agreement drove that point home.

The tactic is obvious: anyone objecting to the latter is immediately pointed back to the former. The retort? ‘You should have spoken up earlier.’

Soft law first. Then hard. It’s a pattern—one you’ll see repeated not just in climate frameworks, but across the entire UN system.

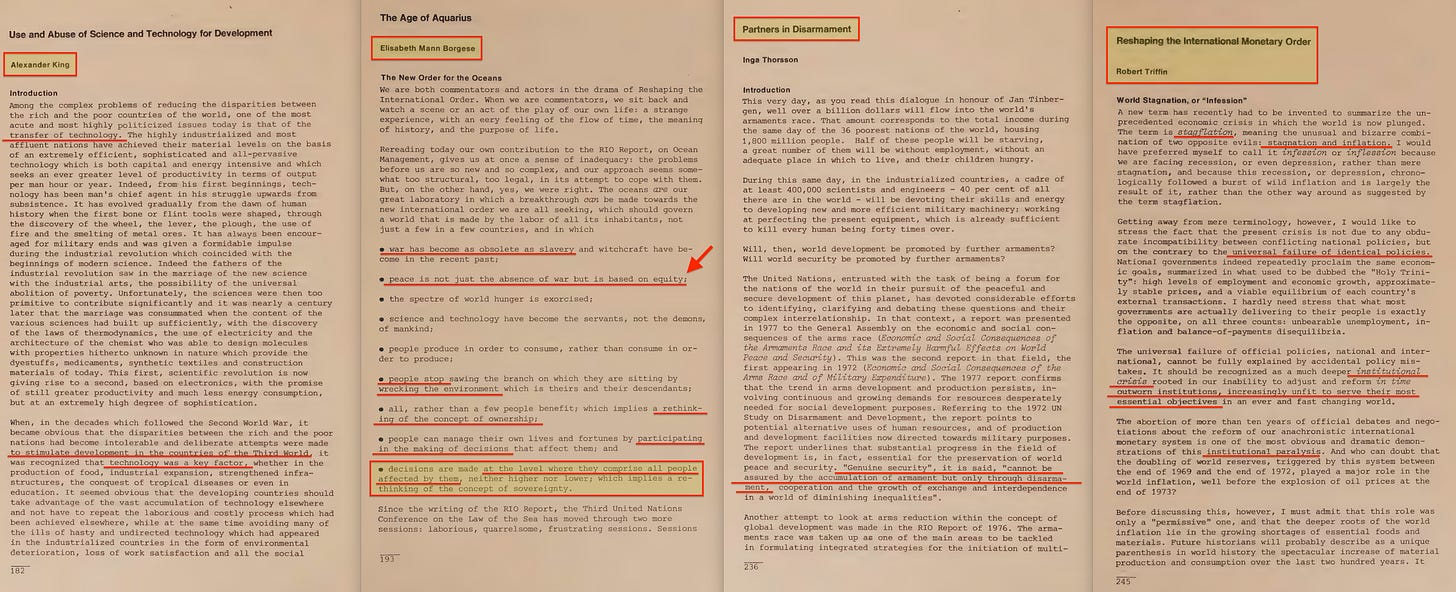

As for the first of the two documents, here is Reshaping the International Order4, published by the Club of Rome in 1976, with the associated conferences having begun in 1974.

We skip straight to Chapter 7. Sure, we could dissect the earlier chapters line by line, but let’s just point out that the word ‘environment’ appears 167 times throughout the book—so there’s no real ambiguity about the context. And if that’s still not enough, Chapter 3 leaves no doubt about the Club of Rome’s 'green' ideological foundation.

But Chapter 7 is where things get especially revealing, because it outlines the structural changes being proposed:

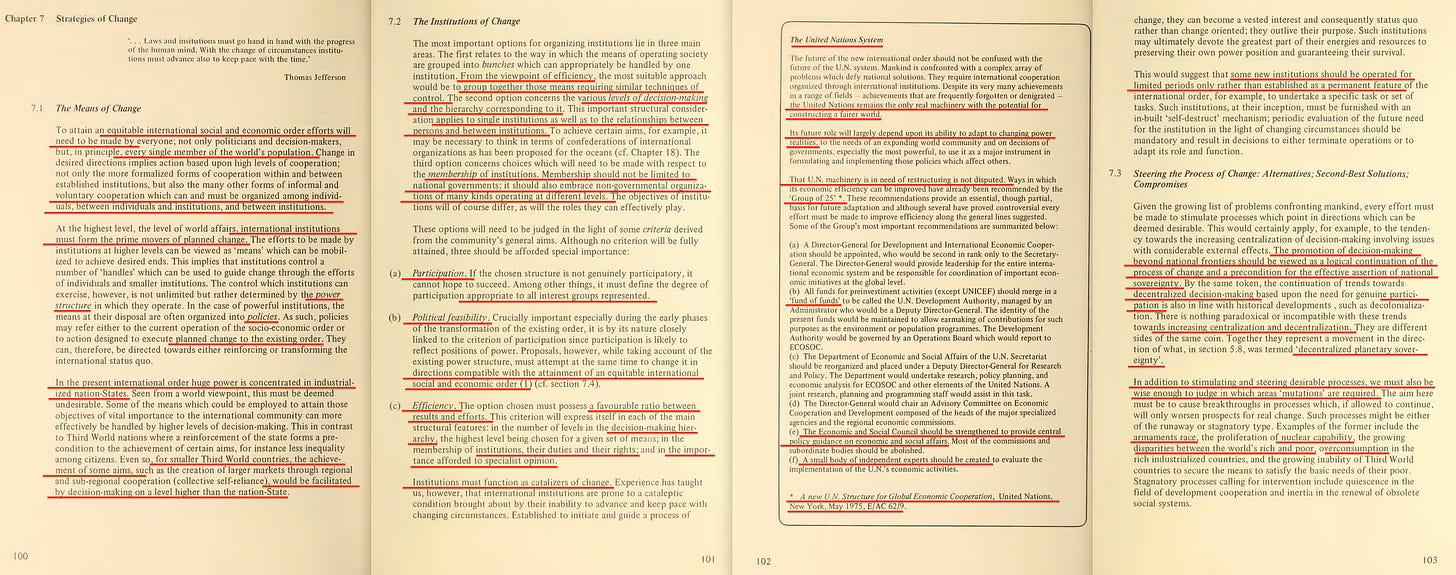

To attain an equitable international social and economic order efforts will need to be made by everyone; not only politicians and decision-makers, but, in principle, every single member of the world's population. Change in desired directions implies action based upon high levels of cooperation; not only the more formalized forms of cooperation within and between established institutions, but also the many other forms of informal and voluntary cooperation which can and must be organized among individuals, between individuals and institutions, and between institutions.

It’s a roundabout way of saying it—but here’s the kicker:

At the highest level, the level of world affairs, international institutions must form the prime movers of planned change. The efforts to be made by institutions at higher levels can be viewed as 'means' which can be mobilized to achieve desired ends.

Wait—what ‘planned change’ exactly are we talking about?

In the present international order huge power is concentrated in industrialized nation-States. Seen from a world viewpoint, this must be deemed undesirable

Ah. Of course. The undermining of national sovereignty. That’s exactly what sprang to my mind too. But don’t worry—they’ve even got strategies for that:

The most important options for organizing institutions lie in three main areas. The first relates to the way in which the means of operating society are grouped into bunches which can appropriately be handled by one institution. From the viewpoint of efficiency, the most suitable approach would be to group together those means requiring similar techniques of control.

Translation: merge organisations. Why have 20 institutions when one will do? Sure, there are a hundred reasons not to—but from their perspective, one will do just fine. After all, it’s far easier to ignore the tedious proles wholesale when you’ve only got one organisation to pretend is listening.

The second option concerns the various levels of decision-making and the hierarchy corresponding to it. This important structural consideration applies to single institutions as well as to the relationships between persons and between institutions. To achieve certain aims, for example, it may be necessary to think in terms of confederations of international organizations as has been proposed for the oceans (cf. Chapter 18).

This sounds an awful lot like subsidiarity in action—decisions delegated just far enough, with anything ‘global’ centralised by default. But in fairness, it’s insufficiently specific at this stage to make a definite ruling.

It could also refer to institutional capacity. Think of the IUCN: it has a full hierarchy of national and regional bodies, effectively forming a quasi-parallel global system allegedly for planetary stewardship.

The third option concerns choices which will need to be made with respect to the membership of institutions. Membership should not be limited to national governments; it should also embrace non-governmental organizations of many kinds operating at different levels. The objectives of institutions will of course differ, as will the roles they can effectively play.

Again—that really does sound like the IUCN.

But options will need to be judged in the light of some criteria derived from the community's general aims:

Participation… appropriate to all interest groups represented.

Political feasibility… while taking account of the existing power structure, must attempt at the same time to change it in directions compatible with the attainment of an equitable international social and economic order.

Efficiency… will express itself in each of the main structural features: in the number of levels in the decision-making hierarchy, the highest level being chosen for a given set of means; in the membership of institutions, their duties and their rights; and in the importance afforded to specialist opinion.

It’s an incredibly long-winded way of saying something very simple. But before we get to what that is, here’s a nice Aesopian fairytale:

The promotion of decision-making beyond national frontiers should be viewed as a logical continuation of the process of change and a precondition for the effective assertion of national sovereignty. By the same token, the continuation of trends towards decentralized decision-making based upon the need for genuine participation is also in line with historical developments, such as decolonialization. There is nothing paradoxical or incompatible with these trends towards increasing centralization and decentralization. They are different sides of the same coin.

During the Brexit referendum, the media was full of talk about ‘pooled sovereignty’5. I can’t tell you how much time I wasted debating this with the pious. I have absolutely no interest in having influence over parking meter legislation in Bulgaria. But by ‘pooling’ our ‘sovereignty’ with Bulgaria, some resident there effectively gained influence over the internal affairs of the UK.

That’s not asserting sovereignty. That’s just wordplay—used by manipulative social scientists.

As for this increase in both centralisation and decentralisation—it all makes perfect sense in the context of subsidiarity. You get local autonomy over which day your bins are collected, while centralised global bodies manage the ‘global commons’—and with that, the imposition of carbon taxation levies… on your bin collection.

And as for what they actually want control over?

In addition to stimulating and steering desirable processes, we must also be wise enough to judge in which areas 'mutations' are required.

That’s right. Even the mutations—the fundamental changes—must be determined top-down. So if you're a nationalist, perhaps you should be banned from elections. If your nationalistic views challenge the framework, maybe the EU bureaucrats should simply refuse to acknowledge your concerns—regardless of whether you're in the majority in your own nation.

Because if planetary sovereignty is the goal, then national sovereignty is just an outdated obstacle—and consequently, your ‘mutation’ should be wisely ignored.

And now, back to the classic practice of saying something—without ever actually spelling it out:

… deterministic blueprints of long range change must be avoided: preoccupation with these may actually jeopardize rather than enhance the prospects for redirecting the process of social evolution. We must of necessity restrict ourselves to a number of guiding principles which can serve as a basis for steering change in desired directions

Translation: We know exactly where we want to go—we’re just not going to admit it in explicit terms, because then you could hold us to account. No, better to keep in vague, because it can then adapt as our objectives evolve. And as for the power structure:

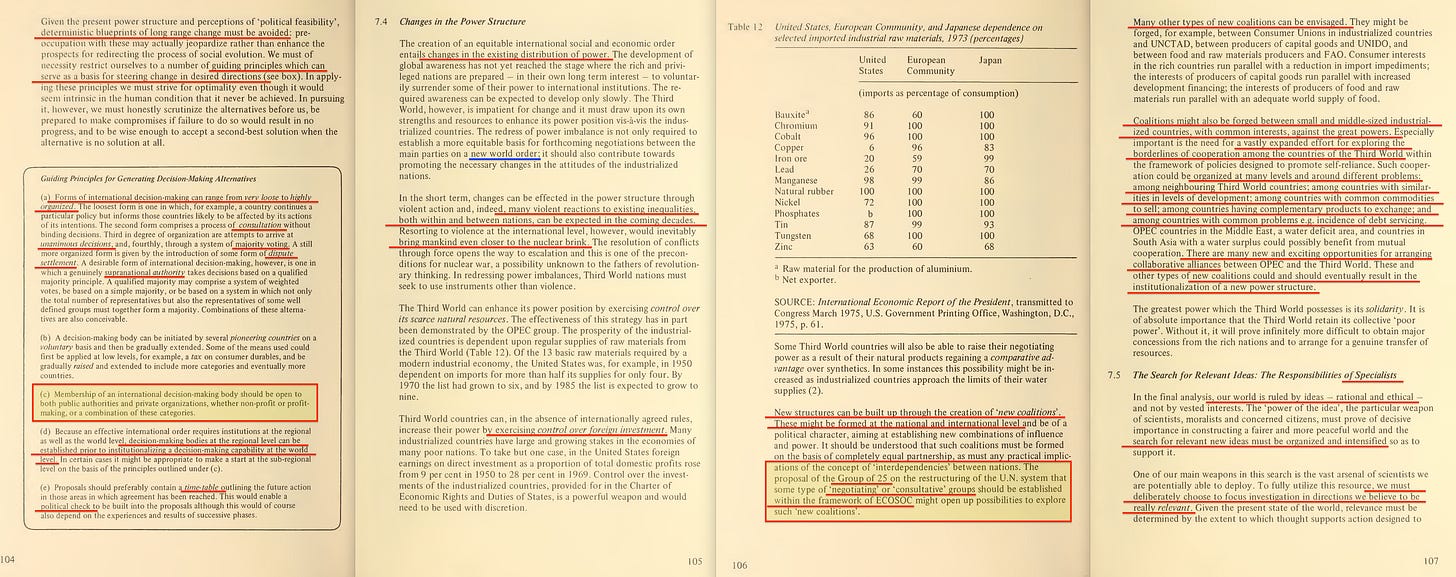

The creation of an equitable international social and economic order entails changes in the existing distribution of power. The development of global awareness has not yet reached the stage where the rich and privileged nations are prepared — in their own long term interest — to voluntarily surrender some of their power to international institutions

In other words: the West should, in effect, voluntarily sabotage itself—because apparently, this is in its own long-term interest.

But how exactly do we generate popular enthusiasm for this enlightened act of voluntary, self-interested self-destruction?

The redress of power imbalance is not only required to establish a more equitable basis for forthcoming negotiations between the main parties on a new world order; it should also contribute towards promoting the necessary changes in the attitudes of the industrialized nations.

Right—by blasting the West with relentless propaganda. And if that doesn’t work?

In the short term, changes can be effected in the power structure through violent action and, indeed, many violent reactions to existing inequalities, both within and between nations, can be expected in the coming decades. Resorting to violence at the international level, however, would inevitably bring mankind even closer to the nuclear brink.

Ah, yes. Through balanced and moderate threats of Nuclear Armageddon. Cool story, bro. The fear-mongering is dialled up to 11—just like when David Cameron warned of World War III if we dared reject the hyper-corrupt6 European bureaucracy7.

What follows is more rhetorical foreplay: hinting at the obvious without ever admitting it outright. Though occasionally, a few lines stand out:

The proposal of the Group of 25 on the restructuring of the U.N. system that some type of 'negotiating' or 'consultative' groups should be established within the framework of ECOSOC might open up possibilities to explore such 'new coalitions'.

This feels like some cosmic object, forever spiralling toward the event horizon—yet somehow never quite falling in. The obfuscation is ridiculous by this point. It’s painfully obvious what they’re inching toward.

Then comes the repetition: the same idea, rephrased a dozen different ways. But eventually, we arrive at something slightly more revealing:

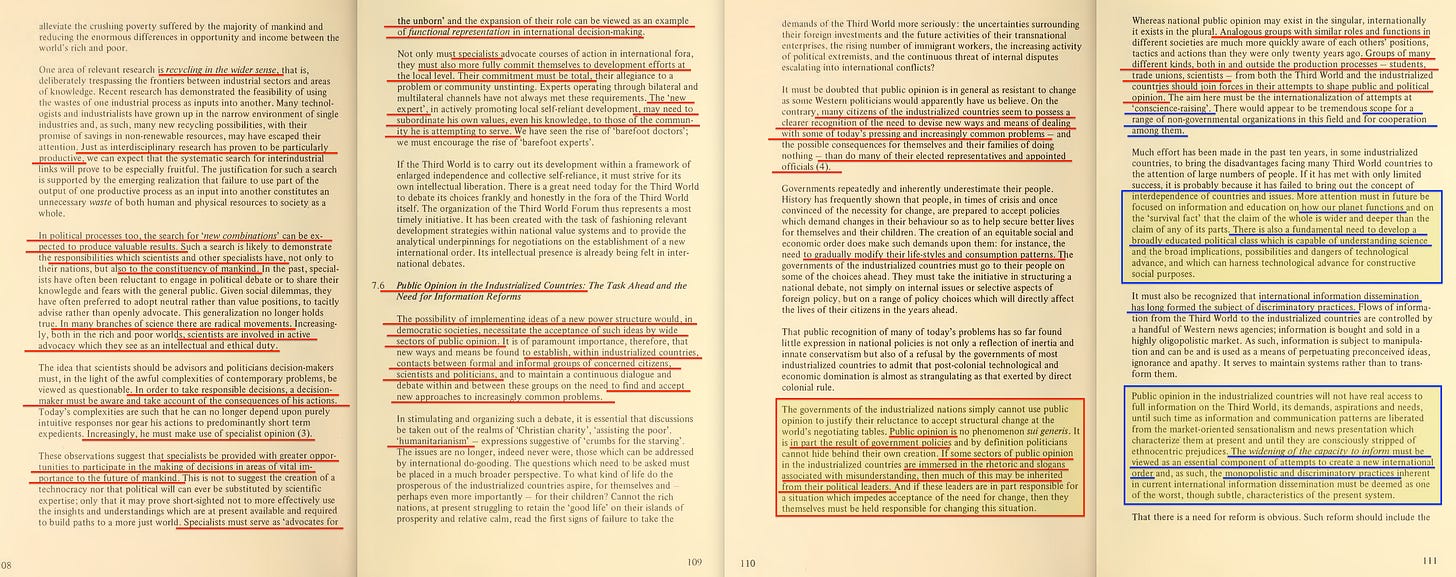

The Search for Relevant Ideas: The Responsibilities of Specialists… our world is ruled by ideas rational and ethical… the search for relevant new ideas must be organized and intensified… To fully utilize this resource, we must deliberately choose to focus investigation in directions we believe to be really relevant. Given the present state of the world, relevance must be determined by the extent to which thought supports action designed to alleviate the crushing poverty suffered by the majority of mankind and reducing the enormous differences in opportunity and income between the world's rich and poor.

So there it is. We must utilise—even direct—science and ethics to serve ‘the common good’. But of course, they decide what’s relevant. They determine the acceptable ideas.

Ideas not considered ‘mutated’.

Next comes a string of stories about material recycling and supply chain reuse—the sort that collapses under even the most basic cost analysis, which, consequently, is never provided

These so-called ‘new solutions’—which are usually neither new, nor actual solutions to the problems claimed—are said to apply to science, especially interdisciplinary research, which we’re told has been particularly productive. Not for you, of course. But the same principle, they claim, can be applied to politics—where, naturally, flirting with centralised power seems like a brilliant idea… if you’re an authoritarian in hiding.

As for scientists themselves? They should ‘acknowledge their responsibilities’. But not just that—they should also be radicals, engaged in ‘active advocacy’ (which, judging by contemporary experience, loosely translates to hurling bricks at police with complete impunity)—unless, of course, their ideas are ‘mutations’. In that case, they must remain silent out of ‘ethical duty’, all of which of course is completely coherent.

You see, scientists must take ‘responsible’ decisions—just as politicians must. So it’s very important that no one pushes ideas not officially sanctioned. Instead, ‘specialist opinion’ must prevail. The kind of ‘specialist opinion’ that definitively declared Covid-19 originated in a bat cave—no questions asked, or social media will permaban your account in a ‘strengthened democracy’ kind of way, faster than Fauci can put on a scientifically proven, common sense second mask8.

Therefore, specialists should be given more opportunities to participate in the democratic debate—which, of course, means they are completely shielded from democratic accountability. Just like the IPCC, IIASA, and ICSU—despite producing little more than politically expedient, targeted pseudoscience dressed up as objectively truthful ‘settled science’ that you’re not allowed to question. This, of course, bears all the hallmarks of quality science—namely, that you must trust it implicitly9. And certainly never challenge it... even as it changes weekly.

And naturally, we must push emotional triggers—invoking ‘future generations’ as cover—while quietly burying those same generations under mountains of public-sector debt from which they will never escape.

To ensure complete ideological incoherence, these same specialists must also ‘commit at the local level’, and may even need to subordinate their own values—because apparently, it makes perfect sense for a ‘specialist’ to bow down to public pressure in the name of science. And in the event you didn’t pick up on my dripping sarcasm, let’s continue through their brilliant satire:

Public opinion must be engineered—democratically, of course—because unpopular opinions tend to be, why, unpopular. And this problem should certainly not be solved through public debate, which could lead to the idea being dismissed entirely. No, far better to engage in subversive opinion-shaping via a continuous stream of carefully crafted lies broadcast on television.

This, they assure us, will help us correct our thinking. We’ll abandon our mutated thoughts and finally embrace the ‘truth’ of whatever deeply unpopular policy our technocratic overlords are so ‘democratically’ attempting to push through—in the process sabotaging our own societies, of course. To protect us.

And to that end, we are reminded:

… many citizens of the industrialized countries seem to possess a clearer recognition of the need to devise new ways and means of dealing with some of today's pressing and increasingly common problems — and the possible consequences for themselves and their families of doing nothing — than do many of their elected representatives and appointed officials…

Ah yes, we’re back to George Soros hiring Purpose Campaign to hurl bricks at police with this mob justice leading to the toppling of statues outside the democratic process—all in the name of ‘public awareness’. But at least it’s for our own good:

The creation of an equitable social and economic order does make such demands upon them: for instance, the need to gradually modify their life-styles and consumption patterns.

And never you mind the rest of the world building coal plants at breakneck speed10.

But as for the public opinion, well, see that’s actually the responsibility of the politician as well:

Public opinion is no phenomenon sui generis. It is in part the result of government policies and by definition politicians cannot hide behind their own creation. If some sectors of public opinion in the industrialized countries are immersed in the rhetoric and slogans associated with misunderstanding, then much of this may be inherited from their political leaders.

That’s right—politicians, they’re coming for you—unless you agree to blast your own populace with Soviet-style rhetoric and fearmongering about an environmental crisis, supported by nothing short of fraudulent data.

Ah, but here’s the trick: if we simply reframe the most controversial parts, all becomes well:

The aim here must be the internationalization of attempts at 'conscience-raising'. There would appear to be tremendous scope for a range of non-governmental organizations in this field and for cooperation among them.

… because then we can draft the NGOs to… er, protect us. But as for those politicians—not only must they be threatened with legal action should they fail to blast their own voters with lies, but perhaps they should be laced with lies themselves:

More attention must in future be focused on information and education on how our planet functions and on the 'survival fact' that the claim of the whole is wider and deeper than the claim of any of its parts. There is also a fundamental need to develop a broadly educated political class which is capable of understanding science and the broad implications, possibilities and dangers of technological advance, and which can harness technological advance for constructive social purposes.

Yes, they should also—in the worst Soviet-style manner—be ‘educated’ to hold the ‘right’ opinion. And that opinion, of course, must align with whatever the ‘specialists’ say—except when the specialist is ethically obligated to stay silent because he must instead subordinate his values.

And to this end, the delivery of information must also be reformed, because the current system quite simply is racist colonialist homophobic sexist discriminary.

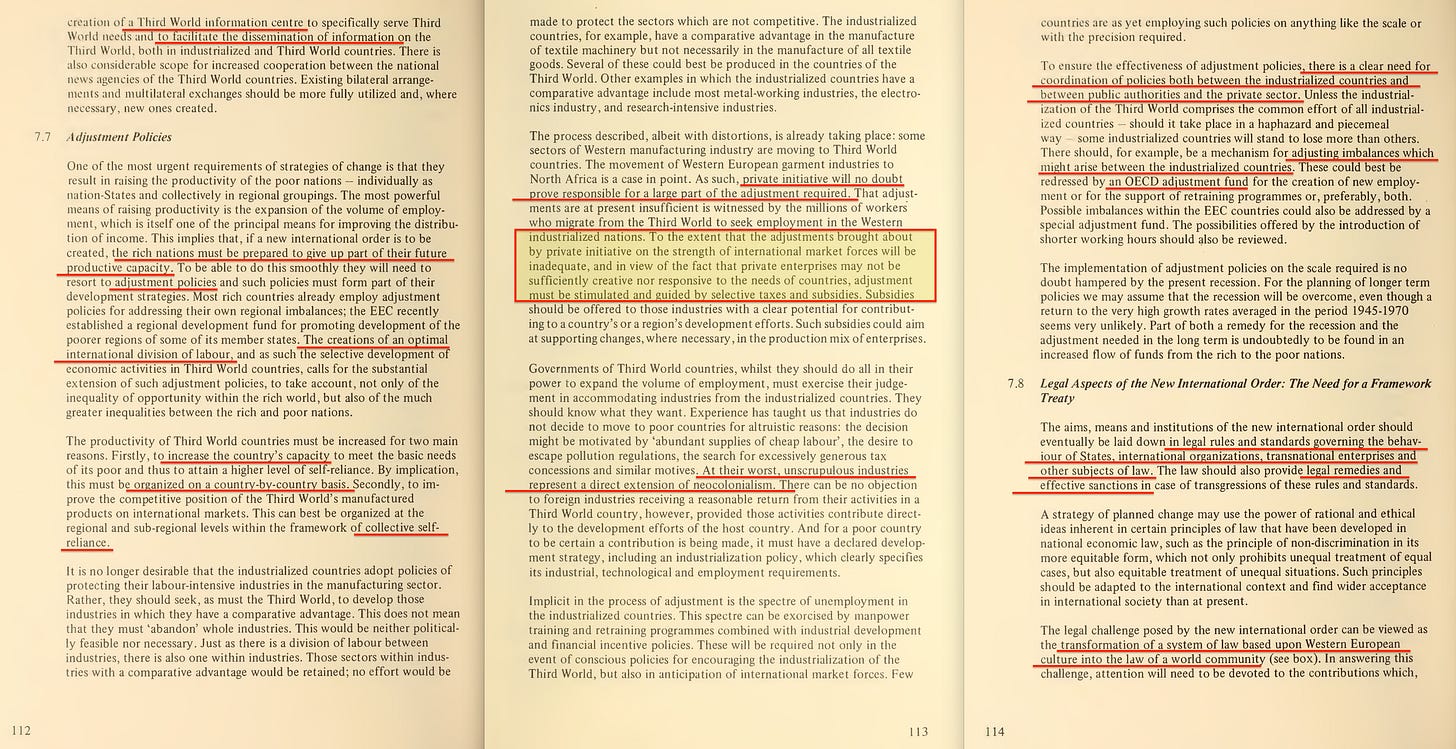

The document continues by insisting that we in the West must yield, and accept the need for ‘adjustment policies’—apparently because the Vikings of Scandinavia once invaded their neighbours, yet have since done little else but war amongst themselves in the most awful, colonial fashion imaginable. And so—naturally—reparations are in order, given the terrible hardship caused by said Scandinavians, suffered by people in… dice roll… Sierra Leone.

Meanwhile, third world nations are encouraged to ‘live within their means’ through a model of collective self-reliance—which is, of course, just as absurd a term as pooled sovereignty. But hey, why stop now?

Anyway, we skip past a few more layers of absurdity and arrive at this:

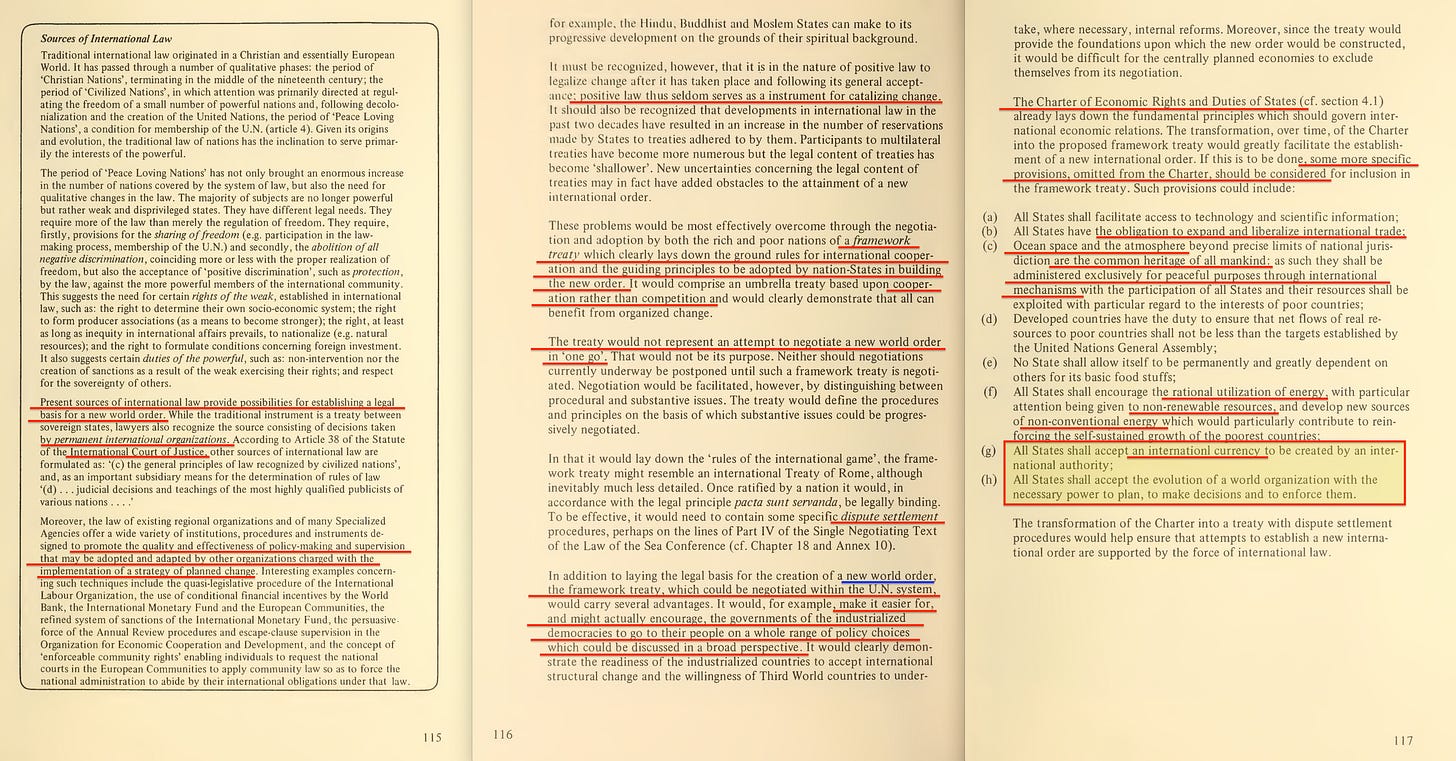

The aims, means and institutions of the new international order should eventually be laid down in legal rules and standards governing the behaviour of States, international organizations, transnational enterprises and other subjects of law. The law should also provide legal remedies and effective sanctions in case of transgressions of these rules and standards.

I’ve lost track of the number of self-contradictions and outright lies crammed into this chapter. The proposed ‘standards’ are, of course, meant to be flexible—which is a polite way of saying they are nothing more than vague guidance, easily rewritten as needed. Likely on the advice of those same ‘specialists’ who are meant to guide politicians—unless, of course, they choose to be ethical and responsible, in which case they must subordinate their own values to public pressure.

Enough of this ridiculous nonsense.

They are Scientific Socialists who wish to be held accountable to no one—while holding you accountable for everything. They intend to seize power through a barrage of carefully engineered lies, and if a politician dares resist this totalitarian doctrine, they’ll be ‘educated’ into compliance.

In the worst, most Soviet sense of the word.

The final few pages maintain the same impeccable standard of… pathological dishonesty. Suddenly, the new world order is rebranded as a framework for cooperation. And, in the spirit of that cooperation, it should—rather conveniently—include a dispute settlement mechanism, to be negotiated under the auspices of the United Nations.

Because nothing says ‘cooperation’ quite like a top-down enforcement structure.

Then we’re treated to a few ‘suggested additions’ to the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States:

All States have the obligation to expand and liberalize international trade;

Expressly as Leonard S. Woolf suggested in International Government—because liberalised trade leads to the breakdown of borders. And:

Ocean space and the atmosphere beyond precise limits of national jurisdiction are the common heritage of all mankind: as such they shall be administered exclusively for peaceful purposes through international mechanisms with the participation of all States and their resources shall be exploited with particular regard to the interests of poor countries;

Which—translated—means global carbon and water markets, monetised under international oversight.

And in terms of energy:

All States shall encourage the rational utilization of energy, with particular attention being given to non-renewable resources, and develop new sources of non-conventional energy which would particularly contribute to reinforcing the self-sustained growth of the poorest countries;

Ah yes, crime-ridden poor nations—those same ones meant to rely on ‘collective self-reliance’—should be handed unreliable technology, especially of the sort which doesn’t work at nighttime. And now, the real punchline:

All States shall accept an international currency to be created by an international authority;

We should what now?

All States shall accept the evolution of a world organization with the necessary power to plan, to make decisions and to enforce them.

Right. So we’re back to communism—complete with a single world bank, a monopoly on credit, and total top-down control.

And all in the name of equity, of course.

In the event it wasn’t quite clear—the above report reads like the equivalent of a Christmas letter to Santa, written by complete authoritarian psychopaths. It’s conceptual, hypothetical, a fanciful wishlist—one that desperately needs translating by people who are, frankly, just better at hiding their mental illness.

Unfortunately, the translators had taken the… year… off—so the practical guide was, by and large, written by the same people. Partners in Tomorrow11 (1978) is the follow-up. And this time, let’s begin with the topic they so absurdly danced around last time, somehow managing to orbit the event horizon without ever falling in.

The Third System.

It begins by outlining just how wonderful this system will be:

… should be seen as an opportunity for widening the discussion through the deliberate participation of individuals, institutions and social forces outside the formal United Nations system.

Naturally, the fact that none of these participants are democratically elected doesn’t matter in the slightest—because democracy, we’re told, will eventually be ‘strengthened’ to fit this new mould:

… the functioning of the United Nations system and to establish a new system of world economic relations based on equality and common interest of all countries".

Of course, what this ‘common interest’ actually is won’t be voted on. But don’t worry—they’re not particularly concerned about that:

Indeed, there is no reason to leave exclusively to governments and intergovernmental machineries the elaboration of the strategy for the future. Societies in their diversity are too rich in values and aspirations to allow governments and organizations, even when democratically established, to represent them fully.

He even explicitly states this won’t be democratic—though naturally, it’s phrased upside-down: you’re not democratically represented, even if your representative is democratically elected.

That, in essence, is what the Third System is all about—a democracy more democratic than democracy itself, by allowing people who don’t represent you to help represent you, thus delivering more democracy… than democracy itself.

Naturally, this calls for the participation of researchers and social organisations. The former, of course, align with those same ‘specialists’ whose advice must be subordinated to those without specialist training. The latter refers to the very subject the first book danced around so absurdly:

The Civil Society Organisations.

And they, of course, should define the needs toward which national development must be directed. That development, we’re told, must be self-reliant—but naturally, in an international capacity. Pooled self-reliance, if you will.

It’s just such terrible Aesopian phrasing. Honestly, I’m offended. I expect more from the technocrats. This is just an insult to my intelligence.

And what’s amazing—yet, sadly predictable—is that Marc Nerfin then spends the next four pages waffling about all the things the system is not. Clearly, this is because he has no intention of exploring the finer details of the public–private–CSO arrangement. Instead, he wastes page after page lamenting the terrible—just terrible—oppressor-versus-oppressed outcomes resulting from the lingering colonial power structures of today. These, he insists, must be urgently reformed so that CSOs can begin managing global affairs—thereby establishing a system capable of enabling worse abuses than anything colonialism ever achieved.

And since the public–private–CSO partnership can broadly be understood as public labour, private capital, and CSO-defined common good, the framework is loosely projected onto the global North–South divide. In this setup, the North provides capital, the South provides labour, and the common good determines which parts of Mozambique… dice roll… Poland supposedly devastated in the past.

The final four pages continue the trend—an attempt to drown out the signal in a flood of buzzwords and empty rhetoric. But buried near the end, in a section highlighted in blue, there’s actually something worth noting:

Finally, the NIEO does require a new structure for negotiation and cooperation. Whatever the recent decisions on the restructuring of the development sectors of the United Nations system, they are likely to fall short of what is required, especially if the timehorizon is the 80s and beyond. Much remains to be done to understand the functioning of the United Nations system, to streamline its functions and organizations, and to formulate alternatives covering the entire system (i.e. not only the General Assembly organs and the specialized agencies but also the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund).

Because when it comes to allocating capital in the name of restoring biodiversity—capital that is then promptly monetised through GEF blended finance schemes—the Bretton Woods institutions are, of course, central. The IMF and World Bank aren’t just ‘included’ in this vision. They are integral to ensuring the machinery functions—quietly coordinating the transfer of wealth under the pretext of saving the planet.

The North–South debate is covered in more detail in arguably the most boring chapter of the lot. But I can’t help dragging it in—explicitly because it’s penned by none other than Barbara ‘Spaceship Earth’ Ward. Yes, the same Barbara Ward who co-authored Only One Earth12 with Rockefeller’s René Dubos13 in 1972, before joining the Conservation Foundation in 1976—whose impeccably detailed 1980 report on monetising air is, frankly, rather telling.

Either way, the proposed solution is North–South collaboration through a ‘Global Compact’—a name that would resurface formally in the year 2000.

And while I could comment on some of the more questionable aspects of her historical… revisionism—for the sake of brevity, let’s skip past that.

She further details how the vacuum left by colonial powers was commonly filled by international corporations—but conveniently fails to point out that this shift logically transfers responsibility to the corporation, not the nation as a whole. But then, that’s rather convenient for someone working—by extension—for Rockefeller.

We also get a chapter on Decision-making for the New International Economic Order—which, logically, should be packed with detail on the public–private–CSO structure.

But no.

It opens, predictably, with the usual flood of buzzwords we’ve come to know and love—but does, in a roundabout way, touch on principles like subsidiarity, participation, cosmopolitanism, and a casual mention of a global planning system.

What’s truly telling, though, is how little space is actually spent explaining how the system works. Instead, the pages are padded with vacuous jargon and standard issue divisive Frankfurt School Critical Theory rhetoric.

Suggestions to issues that aren’t really issues are helpfully added—each one, unsurprisingly, pointing toward the desired structure. And yet, we have to skip all the way to the very final page of the chapter before anything of real substance is finally admitted:

Towards a New Global Compact Really successful negotiation of the NIEO must involve not only governments, but also the other actors. All should know what they are expected to do.

And while they admit it’s ‘not easy to state how this should be done’—without falling into the very traps the essay critiques—they still offer a telling example:

It is not easy to state how this should be done, without making the sort of errors critized in this essay. The work of the U.N. Commission on Transnational Corporations is an example of how private companies can constructively cooperate in and with a U.N. intergovernmental body. Non-governmental organizations of all kinds are supporting U.N. efforts in various directions. The U.N. global conferences have been accompanied by successful private fora.

There it is—the quiet admission: the inclusion of NGOs and private corporations in the realm of public affairs.

Public-Private-CSO partnerships.

Public Labour-Private Capital-CSO Common Good.

The report also includes an early gem titled Global Planning or Chaos, which kindly reminds us that the challenge isn’t just a North–South divide—but also East–West. And, naturally, the East must be included in our glorious future of global planning. In this context, the Trilateral Commission14 also gets a nod—because nothing says representative governance quite like a roundtable of unaccountable elites planning the future of the planet.

And though this top-down authoritarian fever dream sounds utopian—because it is utopian—we’re told the only alternative is chaos. Possibly nuclear armageddon.

And since the Communist nations are definitely going to catch up with the West by 1990 (which of course totally happened), the capitalist nations might as well accept the inevitable and embrace the new world order—full of lollipops, pantomime horses, and a central world institution with the authority to plan, decide—and enforce.

Just in case you had any doubts, the chapter reminds us in no uncertain terms:

The real choice is between a world authority and the laws of the market. And by now everybody knows that the laws of the market systematically work in favor of the rich industrial nations. Sooner or later, a world authority will become a must.

So go on, capitalist nations.

Disarm yourselves immediately.

And accept your lord and saviour, Joseph Stalin.

Finally, let’s zip through two Club of Rome seniors.

Alexander King calls for tech transfers—the kind that typically make middlemen fabulously wealthy.

Elisabeth Mann Borgese, meanwhile, suggests we redefine peace as equity, stop destroying the environment (naturally), rethink the concept of ownership (surely leaning toward Lenin’s ideals), and embrace a participatory democracy where only pre-approved specialists—those who subordinated their own views—are permitted to participate. All major decisions, of course, should be made at the global level, in a similarly democratically accountable fashion—i.e., by specialists selected for their alignment with the agenda.

Then comes the obligatory chapter on the UN’s favourite recurring theme: disarmament. And finally, the inventor of the Triffin dilemma15 chimes in with a plea to reform our ‘outworn institutions’—which, he claims, are ‘increasingly unfit’ to serve the needs of the… emerging technocratic order?

And with that said, I sincerely hope I never have to open that God-awful report again.

I could admittedly have simmered those two reports down. But I intentionally didn’t—because I wanted to be absolutely certain I didn’t miss any critical detail regarding what the objective really was here. And there’s not much doubt.

The primary introduction through the second report was the concept of The Third System. It isn’t mentioned even once in the first report. Sure, you could argue it hadn’t yet been formalised under that name—but that’s a bit odd, given how obsessively they covered the same ground, over and over. At times, it felt like a compact disc with a scratch, getting stuck replaying the same second in an endless loop the very second you lie comfortably in the bathtub.

The former defined the concept. The latter defined its practical implementation.

And all of it ties back to the public–private–CSO partnership, where North and South are fused through a captured civil society layer—controlled quietly by ulterior interests. I could’ve spent more time delving into the environmental aspect, sure—but I honestly don’t see the point. These two reports focus almost entirely on the administrative side of the operation. The environmental components, previously outlined, are simply the operational arm of the same machinery.

In short—planetary stewardship is the justification for public–private–CSO rule—for the common good.

Consequently, environmentalism becomes the operational pretext, requiring a captured Civil Society layer to administer it.

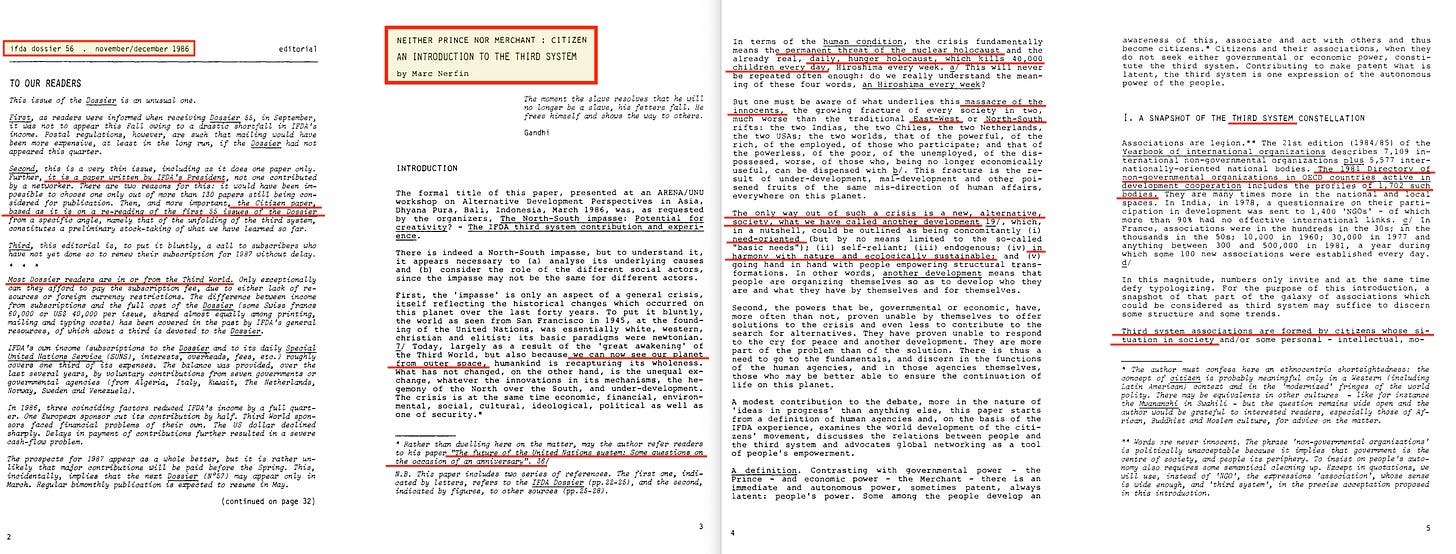

But—you might interject—we haven’t actually had a proper definition of The Third System. And that’s a fair point. So here it is: the special issue of IFDA Dossier No. 5616, where Marc Nerfin himself lays it out in considerable detail.

But first—for those unfamiliar with the IFDA, let’s just say it was an organisation devoted to ‘alternative development’ of the distinctly progressive kind—complete with Maurice Strong on the roster17.

As for Marc Nerfin’s essay… honestly, I see no reason to cover it in depth. It’s allegedly about the environment. It’s about ‘sustainable development’. It’s about East–West, North–South, the looming threat of nuclear holocaust—and, of course:

It’s about NGOs riding in to save us all from these carefully manufactured horrors.

To solve all these alleged problems, people must join up—and their associations must participate in decision-making (provided, of course, their ideology isn’t ‘mutated’).

These Civil Society Organisations come in all shapes and sizes. They operate at local, regional, national, and global levels—or even simultaneously at multiple levels (if you’re the IUCN, certainly). They are specifically created to address specific problems—thus becoming common goods. Through this structure, we are told, the New International Economic Order18 can finally be realised—or perhaps even that same federalist world so eagerly propagated by the leading communists of the 1960s19... such as the Club of Rome’s Elisabeth Mann Borgese, who co-authored the 1947 draft.

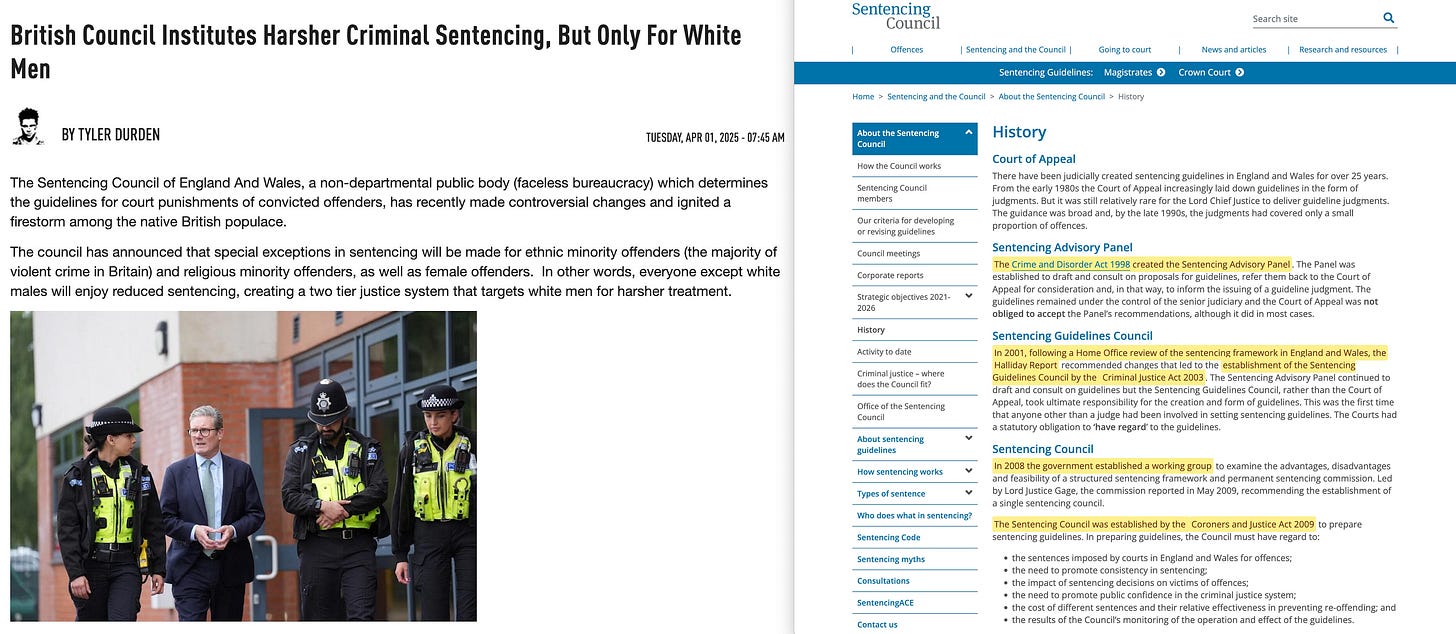

Naturally, this all requires strong female participation—because, as we are informed, everything men touch turns to ruin. Especially if those men happen to be white and heterosexual, crimes for which Keir’s Fabian government think you should be punished20—though Gordon Brown’s government in 2009 at least had the common courtesy of abstracting into a QUANGO21, lest Labour be forced to accept responsibility for this act of blatant racism. Any objections to these self-evident facts, of course, mark you as a colonial, homophobic racist. And so on.

As for accountability and enforcement, we’re assured these principles will apply—though in practice, that enforcement will most certainly not be bidirectional.

Next, Marc tells us that the term The Third System was first coined between 1978 and 1980—which is interesting in itself, considering Marc Nerfin had already titled a full chapter titled as such in those exact words in Partners in Tomorrow covered above, complete with a foreword dated… February, 1978.

From there, the piece meanders into a historical narrative of questionable legitimacy, tosses in a dose of Critical Theory’s oppressor-versus-oppressed framing, and drags in medieval guild systems—those same systems that led to bloodshed and mass oppression (though, curiously, Nerfin doesn’t find room to mention that part).

Then—for good measure—he starts parading around a few politically convenient remarks about the mainstream media—which, of course, conveniently doesn’t fit into the Third System model he promotes. Never mind the fact that this media is supposed to engage explicitly in behaviour that would, by any definition, be considered state-sponsored psychological manipulation—sorry, public engagement for planetary consciousness. My mistake.

Besides, all of this circles around the sacred tenets of social justice—and thus, you’re not allowed to speak up. Doing so would endanger our democracy, or worse, threaten the democratic participation of minorities, no doubt.

Either way, we must keep a keen eye on those citizens who are not naturally good—those who might fall prey to manipulation. Though not our manipulation, of course. Ours is for the common good, and thus conveniently satisfies both the surveillance and moral superiority clauses in one go.

Look—I can’t do this anymore. The lies are just… continuously… breathtaking.

No, really. Here’s the next one:

The third system does not seek governmental or economic power. On the contrary, its function is to help people to asser their own autonomous power.

It’s such epic bullshit, one has to wonder just how many Rockefeller-funded social scientists it took to wordsmith that contemptible horse manure into existence. But then again, I just cannot let this next one slide either:

… the oneness of humankind and its planet. The risk of nuclear holocaust and the cojonction of under-development and maldevelopment also make us one. Environment and health hazards underline out interdependence.

Naturally, it then proceeds to recommend a full restructuring of the United Nations—this time in line with the federalist movement of the 1960s. You know, the one teeming with communists, including Einstein. And to really sell the idea? They draft in none other but James P Grant22—yet another Rockefeller-funded ‘specialist’—to help package it for public consumption.

Finally, the essay ends with a full-blown buzzword bonanza—similar to those iPhone games where explosions go off every five seconds to entertain people whose dopamine receptors have long since been fried. Years of dragging pointless blocks across a tiny screen, just to feel something—anything—in a life otherwise drained of all meaning… and, apparently, some public policy documents are being written the same way.

Holy shit, I somehow made it through that epic trash. Well done, me.

Hey, you got the summary—I had to actually read, comprehend, and highlight this steaming pile of ideological garbage, connecting these reports ideologically, each one crafted to sell you on a vision tailor-made for conspiring commies in conference lanyards.

So let’s finish off with an outline of what came next.

The G77 were essentially presented with an ultimatum: accept this one-sided deal, or lose development aid. They accepted—of course they did—regardless of the fact that what they were signing onto was a breathtaking geopolitical garbage patch. Then followed the concept of Good Governance which through the World Bank demanded civil service reform in 1992, and through the UNDP electoral reform in 1997—or else development aid would be cut off. Ethically, you see.

With the Third World wrapped up, the Second World came next. And on November 4th, 1987, Mikhail Gorbachev delivered a speech that changed everything—outlining a strategy to defuse the fear of the Soviet threat, thus enabling the synthesis of East and West… through environmentalism.

And that is fully sourced.

And as Tony Blair submitted his essay to Marxism Today in 1991—promoting a worldview virtually indistinguishable from that of revisionist Marxist Eduard Bernstein—the Iron Curtain conveniently fell. The Soviet Union allegedly collapsed, paving the way for the long-planned synthesis of the capitalist West and communist East—exactly as Gorbachev had outlined back in 1987.

The Third World had fallen victim to this model of quiet exploitation. The Second World followed. Only the First World remained.

A First World now drowning in social science applications of Frankfurt School Critical Theory—with men being set up versus women, black vs white, straight vs gay and so forth—each designed to insert a mediating entity between two allegedly conflicting forces. A mediating entity which—not coincidentally—aligns perfectly with the core model at play.

A strategy first outlined by Alexander Bogdanov, as it happens.

And with Blair’s Third Way pushed through the Fabian Society, Wolfgang Reinicke’s Trisectoral Networks soon followed—building directly on Kofi Annan’s 1997 UN structural reform, itself drafted by none other than Maurice Strong.

The whole world was to be controlled in feudal fashion through principles of subsidiarity—and a model first laid down in detail by Eduard Bernstein in 1899, three years before Lenin and Alexander Bogdanov founded the Bolshevik Party. Bernstein, influenced by the economic theories of Julius Wolf, sought to merge socialism with international institutionalism—replacing revolutionary upheaval with technocratic administration. His revisionist model was later advanced by British Fabians such as Leonard S. Woolf, and echoed by internationalist thinkers like Alfred Zimmern, who helped shape the structural framework that gave rise to the League of Nations and, eventually, the United Nations.

Julius Wolf, for his part, had outlined in 1892 a system of gold-backed credit clearances between states—a global financial mechanism that effectively turned international trade into centralized accounting. This concept was later embedded in the architecture of the Bank for International Settlements at its founding in 1930. Together, Bernstein’s governance framework and Wolf’s monetary infrastructure formed the dual engines of a global system—capable of administering the planet through supranational rule, justified in modern times by the IUCN’s doctrine of planetary stewardship.

And this parallel structure—controlled by ECOSOC-registered NGOs with General Consultative Status and the Bank for International Settlements—was to be advanced through Proletkult-style propaganda, aligned with Frankfurt School Critical Theory, both designed to facilitate the same mechanism:

A governance model fundamentally centered on a mediating entity—unelected, unaccountable, and operating under the mask of moral legitimacy. Not democratic. Not representative. And never, ultimately, accountable.

For the common good.

![WHO Pandemic Agreement [April, 2024]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!HHbL!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb69c8066-0498-4924-af63-1344abb2ec85_1206x612.png)