Alexander Bogdanov

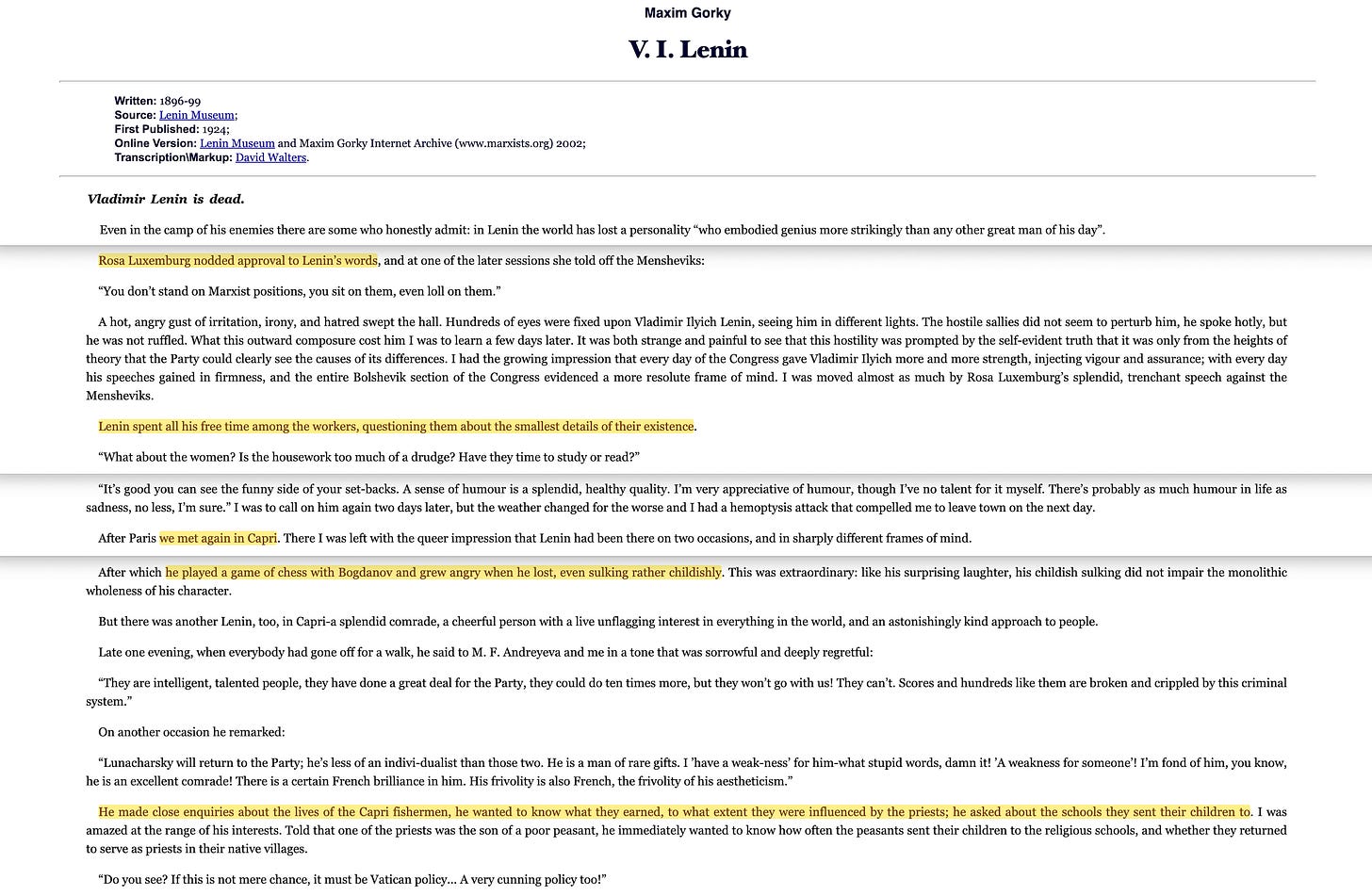

He may well have been the brightest mind to ever grace this earth. In due course, he could well become the most influential, too. And yet, chances are you never even heard of him. And here he is, playing White, facing off against Vladimir Lenin in a game of chess.

A match he - prophetically - won.

The third figure in the picture is Maxim Gorky, who later recounted that this game was played in Capri, Italy, in 1908. And while Gorky noted Lenin's habit of inquiring with the common man about his troubles, he further revealed that1 -

‘… he played a game of chess with Bogdanov and grew angry when he lost, even sulking rather childishly. This was extraordinary: like his surprising laughter, his childish sulking did not impair the monolithic wholeness of his character‘

But during that same trip, Lenin also ‘talked about the anarchy of production under the capitalist system‘, in which context he suggested to Bogdanov -

‘You ought to write a novel for the workers about how the capitalist predators have ravaged the Earth, squandering all its oil, iron, timber, and coal‘

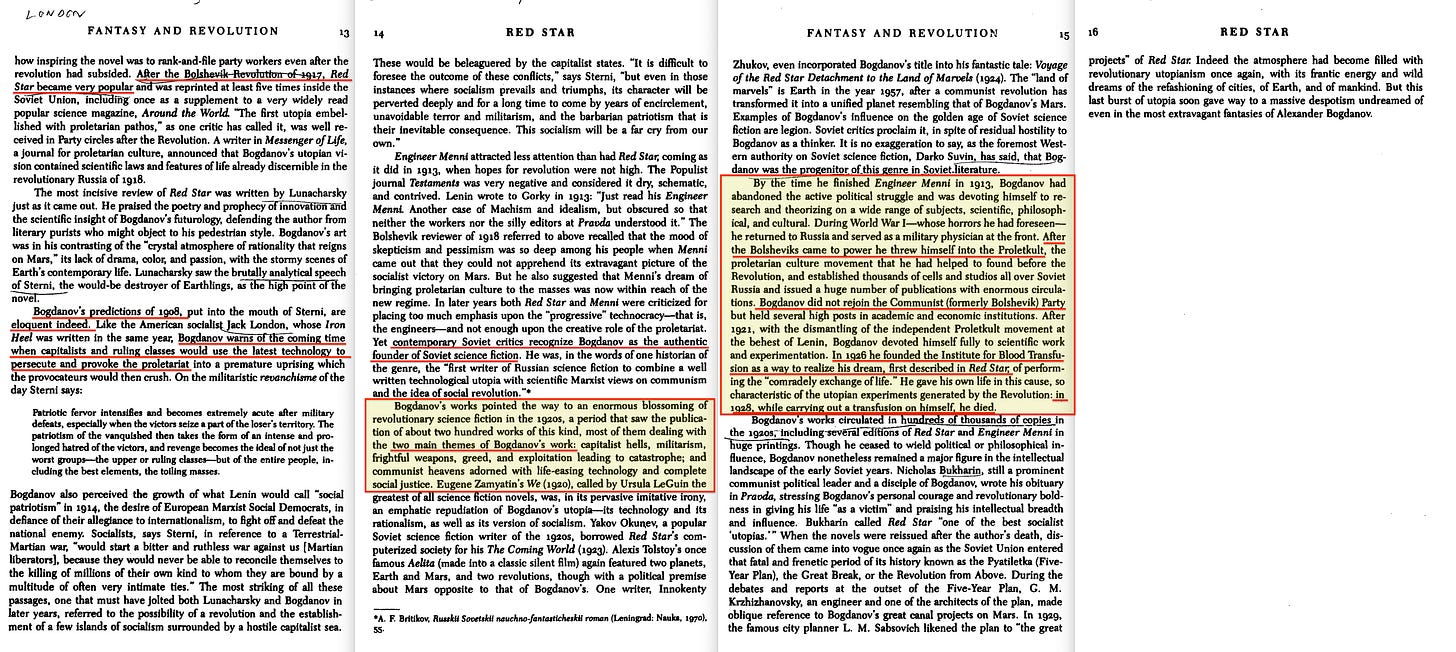

It all appears… so strangely prophetic, but this really is just the beginning. And in 1908 - the same year as the chess game - Bogdanov authored a novel that would lay the foundation for the Soviet science fiction genre ‘Red Star - The First Bolshevik Revolution’2.

The novel itself lies beyond the scope of this post, but the introduction deserves attention, as Richard Stites notes the Martians in Bogdanov’s novel state -

‘… in order to wage the struggle we must know that future‘

And that is an interesting, even telling inclusion, but Stites goes on to detail the dual nature of his desired revolution -

‘… the kind of society that could emerge on Earth after the dual victory of the scientic-technical revolution and the social revolution…‘

… before providing us a brief history of the Bolshevik and Menshevik parties, both of which rose from the Social Democratic Party, a political party comprising of… Russian Marxists.

Social Democrats, you say?

Stites continues by describing Bogdanov’s belief that ‘Marx needed an update’, one rooted in the application of science and organisation, and to this end Bodanov set himself the ambitious goal of creating a super-science bridging the two - an endeavour, ultimately giving rise to Tektology, the precursor of General Systems Theory, Cybernetics, and Systems Thinking as we know it today.

The novel portrays Mars as the perfect socialist society, a world without peasants, nationalities, states, or politics. Here, ‘everyone is a worker who produces according to capacity and consumes according to desire‘. It further introduces a ‘death ray’, later elaborated upon in a subsequent chapter -

‘The superior technology of the Martians win mean that the Earthlings cannot win this struggle, but the militant spirit of the Earthlings will guarantee an indefinite and costly war. The only way to avoid this ordeal, said Sterni, is to wipe them out in advance with death rays, and then use the riches of Earth to build a more humane socialism on Mars.‘

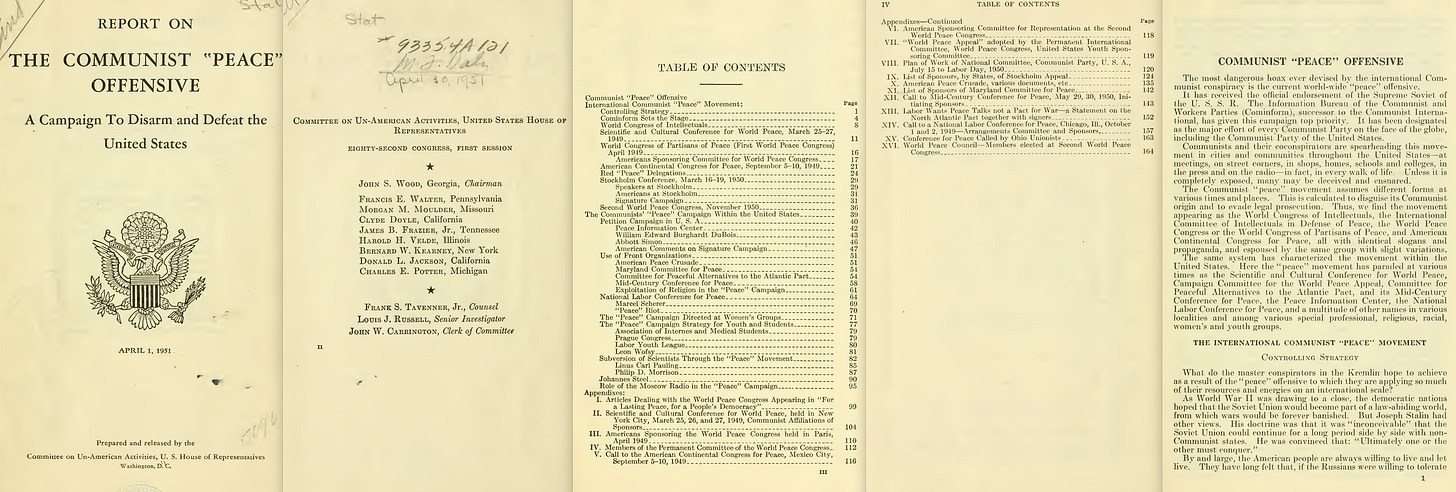

… an ideology almost exactly in line with that discussed by the Committee on Un-American Activities in 19513.

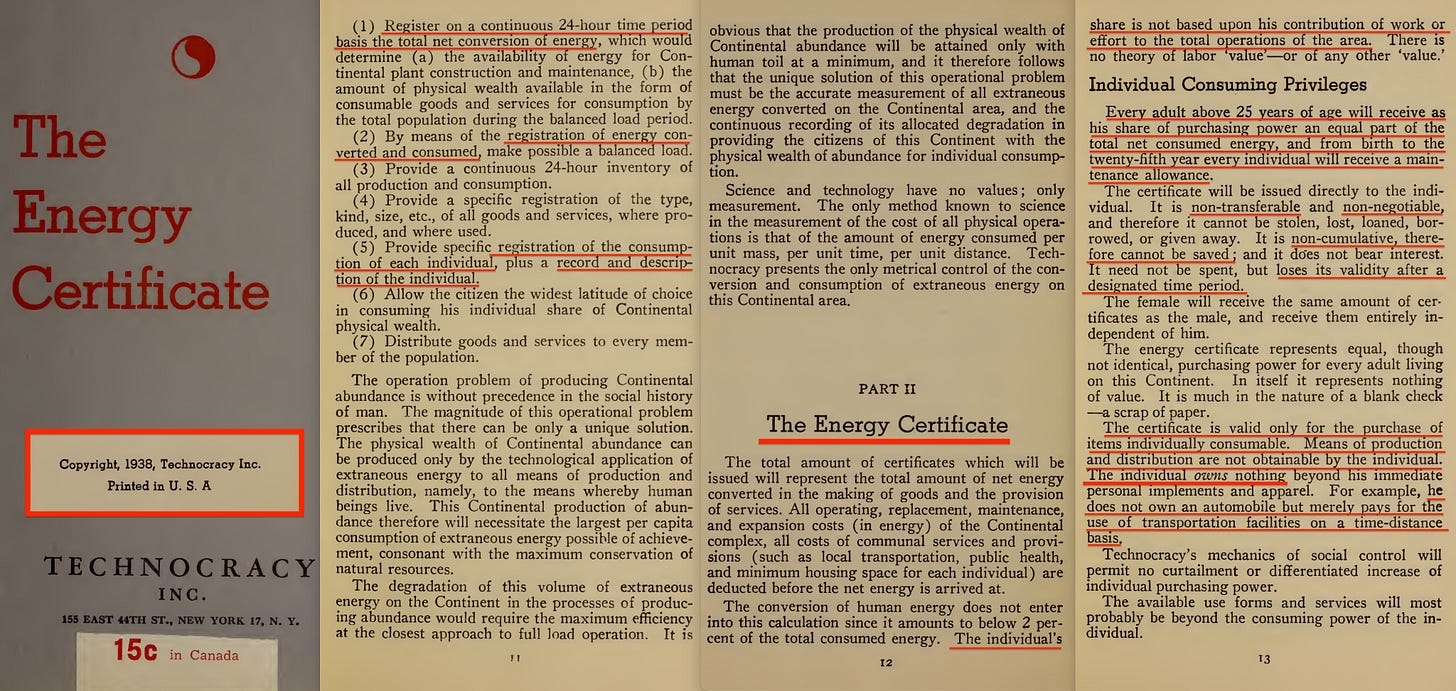

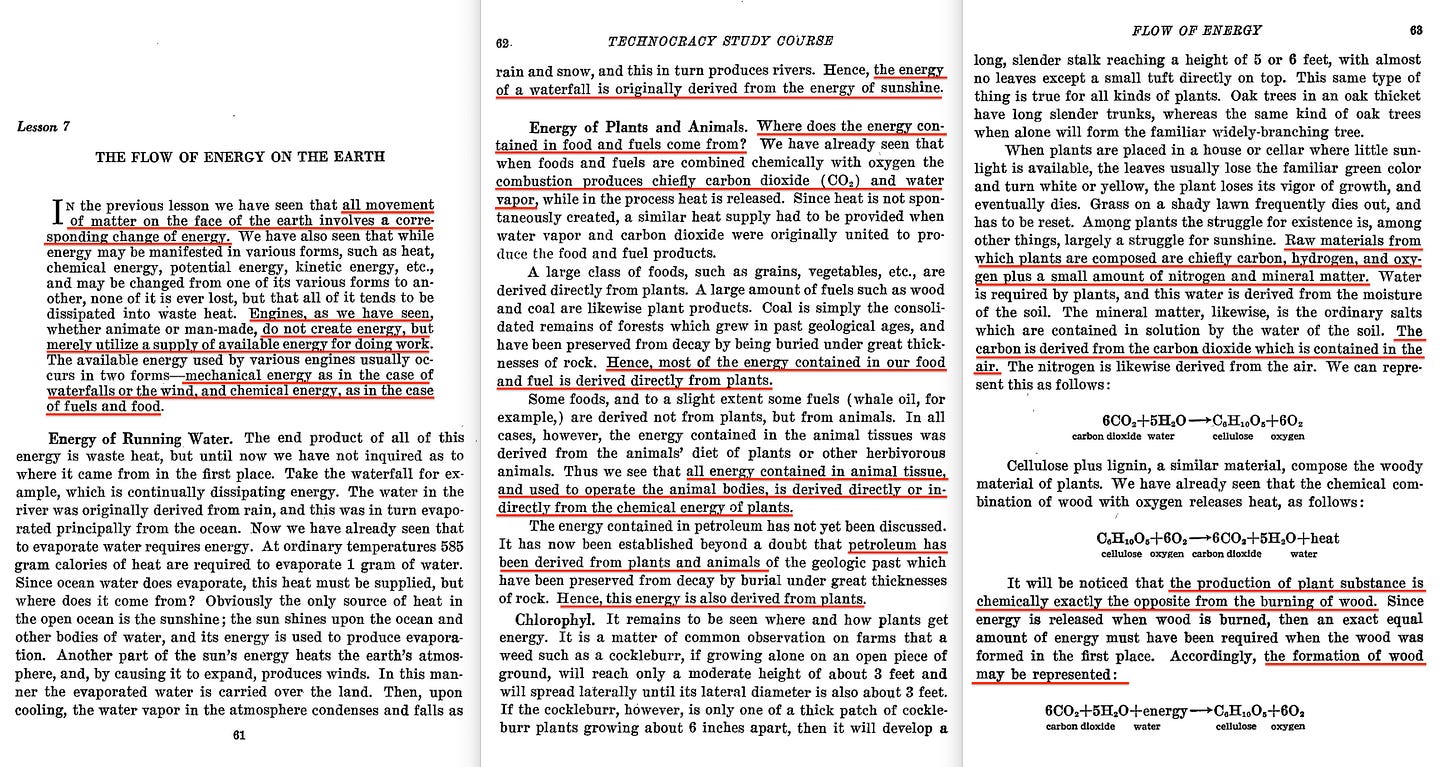

The book goes on to describe a technocratic system of production, where everything is fully automated by machines, and all related data meticulously monitored - a somewhat prescient inclusion, given how closely this vision aligns with the objectives of the Technocracy Inc movement emerging decades later (1936), though Technocracy Inc would go on to apply these principles in context of energy4 management5 to the extent of detailing the bi-directional nature of the carbon cycle; carbon emission through the burning of wood, and carbon sequestration through the growing of trees - a chemical process which, in contemporary terms, anticipates discussions at the Earth Summit in Rio, 1992. And notably, this study course was written by MK Hubbert who later introduced the concept of ‘peak oil’6 to the public in 1956.

Next, Stites describes the novel's utopian, collectivist vision, where everyone serves ‘a common will’, and no-one is above the rest. And this harmony is maintained through the ‘comradely exchange of life’, symbolised by blood transfusions - a concept that, in real life, claimed Bogdanov’s own life in 19287.

The narrative then provides more historical context, revealing that Bogdanov opposed sexual liberation, viewing socialism as inherently tied to aspirations of high moral behavior. It also notes that, following the failed 1905 revolution, Bogdanov and his fellow revolutionaries left for Europe, hence their stay Capri.

But Bogdanov lost the internal Bolshevik power struggle to Lenin, prompting his retirement from politics, and he thus decided to ‘devote his time exclusively to the organizational science and proletarian culture.‘

And those focal points are crucial, because while we need to seek for an answer to the latter, the former is explained through Tektology, and -

‘Bogdanov's answer… is the creation of a unified science of organization that will link all the sciences, currently fragmented, to the processes of labor and life‘

Empiriomonism, essentially.

And Bogdanov really was rather the visionary -

‘… predictions of 1908… Bogdanov warns of the coming time when capitalists and ruling classes would use the latest technology to persecute and provoke the proletariat into a premature uprising which the provocateurs would then crush‘

… because we presently live in a world of ‘cultural energy’, where the ruling classes continuously set us up against one another, not least visible in Ireland through the setting aside of voter concern and inviting migrants at breakneck pace, leading to said minor uprisings, easily struck down.

And as for the founding of the Soviet Science Fiction genre -

‘… two main themes of Bogdanov's work: capitalist hells, militarism, frightful weapons, greed, and exploitation leading to catastrophe; and communist heavens adorned with life-easing technology and complete social justice‘

… this similarly appears close to contemporary settings. And with mention of Bogdanov getting involved with proletatian culture (and Lenin striking down said) the paper completes.

Consequently, we have his efforts relating to Tektology on one side, and Proletkult on the other. And let’s begin with the former, as this is a frequently covered topic on this substack.

Simona Poustilnik’s paper, ‘Alexsandr Bogdanov’s Tektology: A Science of Reconstruction‘8 details that Tektology is meant as a universal science of organisation, leading to a better world and humankind, but that it further serves as a precursor of not only Bertanalffy’s General Systems Theory, but also Norbert Weiner’s Cybernetics.

And Bogdanov’s Tektology was meant to facilitate the Marxist revolution without a violent class struggle -

‘Russian Marxism had seen the revolution and class struggle as the way towards achieving a new social order. Bogdanov had an opposite vision; the idea of struggle did not fit in with Bogdanov’s organizational and harmonic vision of the world. Tektology was an “allhuman science” for the gathering together of man and of the world, to produce a scientifically organized collective by stage of self-organization without class struggle‘

… and to this end -

‘… science played a primary role in Bogdanov’s conception of scientifically organized humankind… Science would be available to everyone and the human collective would be able to control it.‘

… but why should science be available to everyone? Well, the answer here - quite simply - is yet another example of his extreme levels of intelligence -

‘Bogdanov’s answer was Tektology as the “socialism of science”… Bogdanov formulated the task of changing “a fractured man” into “integral man” when knowledge would be the property not of an élite, but of all members of the collective. It was the hope of replacing the existing necessity of collective belief by the collective possession of knowledge that motivated Bogdanov in his path towards Tektology‘

Bogdanov wanted the principles of Tektology to be embedded in science as a universal framework. And once science became accessibly to everyone, it would serve as the foundation of collective understanding and organisation, and would thus eliminate the need for a collective belief system such as ideology or religion, because the unifying principles of Tektology - as delivered through science - would provide a rational, shared basis for societal cohesion and progress. Scientific Socialism.

And as for the cultural aspect -

‘In Bogdanov’s own words, Tektology was an “all-human science” – an instrument for the organization of humankind into “single intelligent human organism” and the purpose of the Proletkult was to open the path towards socialism by serving as an enabling institution for cultural self-organization and the mastering of Tektology‘

Tektology serves as the framework, enabling the creation of the ‘human super-organism’, while proletkult functions as the cultural and educational movement, designed to guide people towards this collectivist vision.

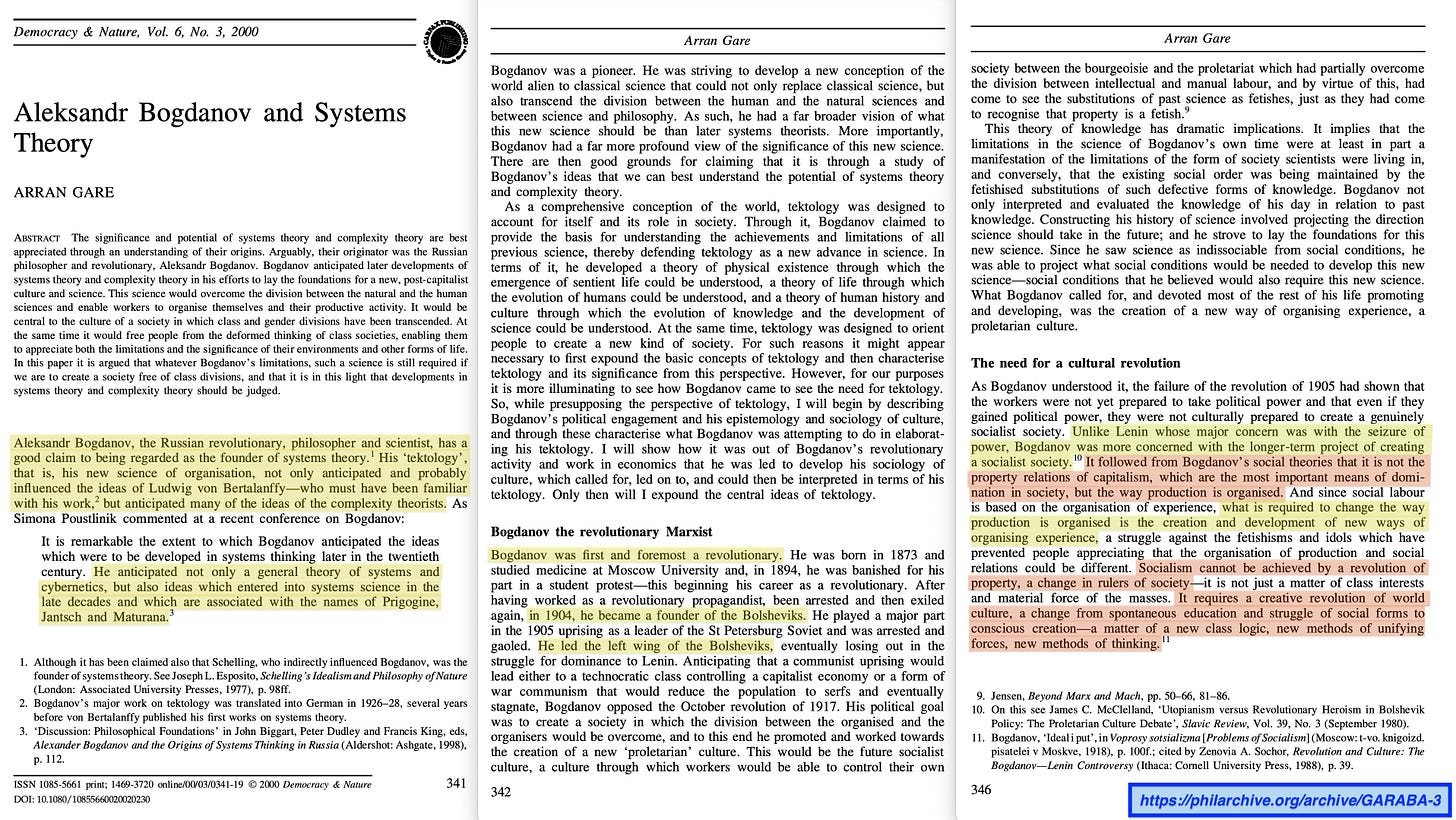

Allan Gare’s paper from 2000, ‘Aleksandr Bogdanov and Systems Theory‘ is more detailed in this regard. First, we find agreement related to Systems Science in general, but further that Bogdanov was the genuine revolutionary, as -

‘Unlike Lenin whose major concern was with the seizure of power, Bogdanov was more concerned with the longer-term project of creating a socialist society‘

To this extent, Bogdanov realised that -

‘… it is not the property relations of capitalism, which are the most important means of domi- nation in society, but the way production is organised’

The elite of society does not comprise the owners of capital as Marx had established, but rather those who organise production -

’… what is required to change the way production is organised is the creation and development of new ways of organising experience… Socialism cannot be achieved by a revolution of property, a change in rulers of society—it is not just a matter of class interests and material force of the masses. It requires a creative revolution of world culture, a change from spontaneous education and struggle of social forms to conscious creation—a matter of a new class logic, new methods of unifying forces, new methods of thinking.‘

Consequently, Bogdanov proposed a change in mindset to facilitate this transition, and this would come about through the development of a new culture rather than merely transferring private property rights to a new set of owners, a solution he regarded as insufficient for achieving long-term societal transformation.

Now, hold on to your hat, because unlike Marx, Bogdanov didn’t see just materialism being a battleground but rather -

‘Apart from property relations and the organisation of production, all social relationships based on domination and subordination, whether these be based on sex, race, class, nationality or possession of technical knowledge, are sources of conflict which must be criticised and overcome by the proletariat.‘

… absolutely every sphere of human experience imaginable -

‘Bogdanov also paid attention to male–female relationships as problematic, as needing to be transformed by the proletariat. Consequently, a genuine revolution is not something that could be achieved by one gigantic act of will in which power is seized, but is a transformative process involving many levels‘

… even to the point of causing strife among the genders. And to aid this objective, Bogdanov argued that -

‘Art, literature, philosophy and science were all accorded importance by Bogdanov as ideological labour, their object being a transformation of the way people organise their experience to achieve a common understanding of the world. In opposition to orthodox Marxists, Bogdanov argued: ‘Art … is a most powerful weapon for the organization of collective forces and, in a class society, of class forces’.‘

Consequently, art is a primary tool to facilitate the transition, but -

‘According to Bogdanov, science would be the most important component of the new culture because it bridges the gap between ideological and technological knowledge. Recent developments in science, themselves manifestations of the change in work and work relations, were seen to be already portents of the new socialist society‘

… science was the overriding tool leading society there.

A discussion follows which outlines Bogdanov’s view on circulatory energy flows as a substitution for labour, before Gare discusses more recent ‘holistic’ framework developments -

‘Since Bogdanov, other historians of science have examined the close relationship between ideas upheld as scientic and socio-economic and gender relations. Joseph Needham and Margaret Jacobs have shown the ideological function of mechanistic thinking in the emergence of capitalism in the seventeenth century‘

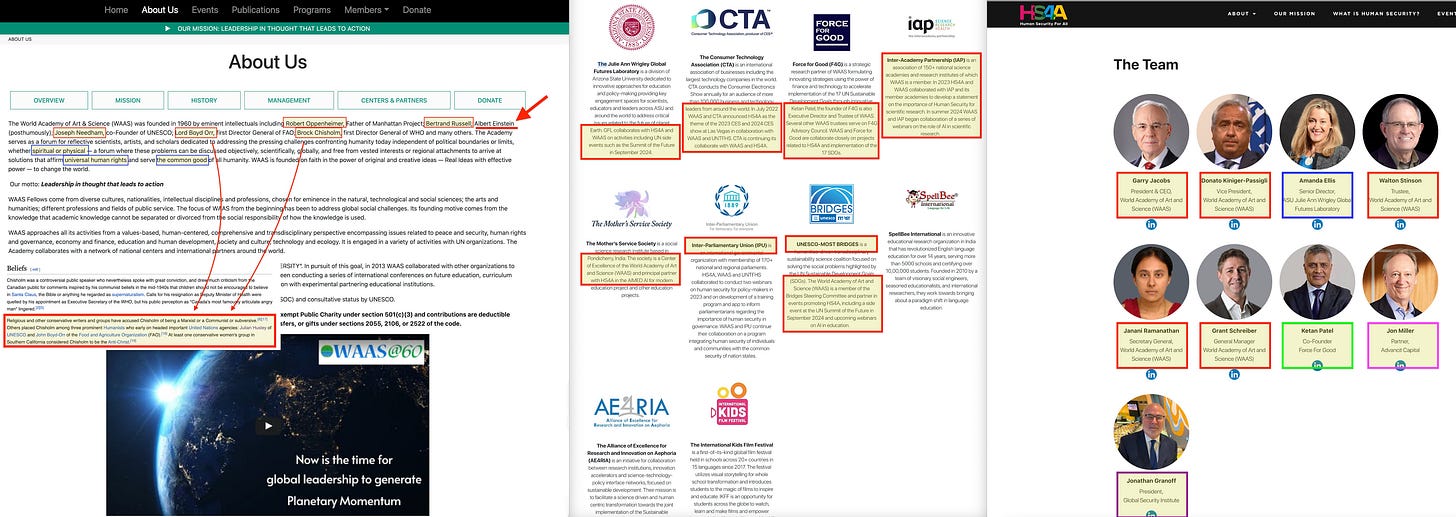

Joseph Needham was not only a Marxist co-founder of UNESCO9, but he further co-founded The World Academy of Arts and Science in 196010… along with Einstein11 and other leading hardcore socialists… where the WAAS in more contemporary settings is connected to the initiative of ‘Human Security 4 All’12.

Oh, but there’s more -

‘Feminists and environmentalists such as Evelyn Fox Keller and Carolyn Merchant have exposed the biases produced by oppressive gender relations in favour of scientic theories that facilitate the domination and control of nature and people. Other social theorists, notably Lukacs, Gramsci (who was probably influenced at least indirectly by Bogdanov) and members of the Frankfurt Institute have argued for the central importance of consciousness and culture in preventing or facilitating the creation of a new society‘

… though I’m not sure there’s much more to comment on. Bogdanov identified not only materialism but EVERY strata of society as a potential battleground, leading to the progressive transition to Marxist Socialism, with Joseph Needham, feminists and even the Frankfurt School operating in his wake.

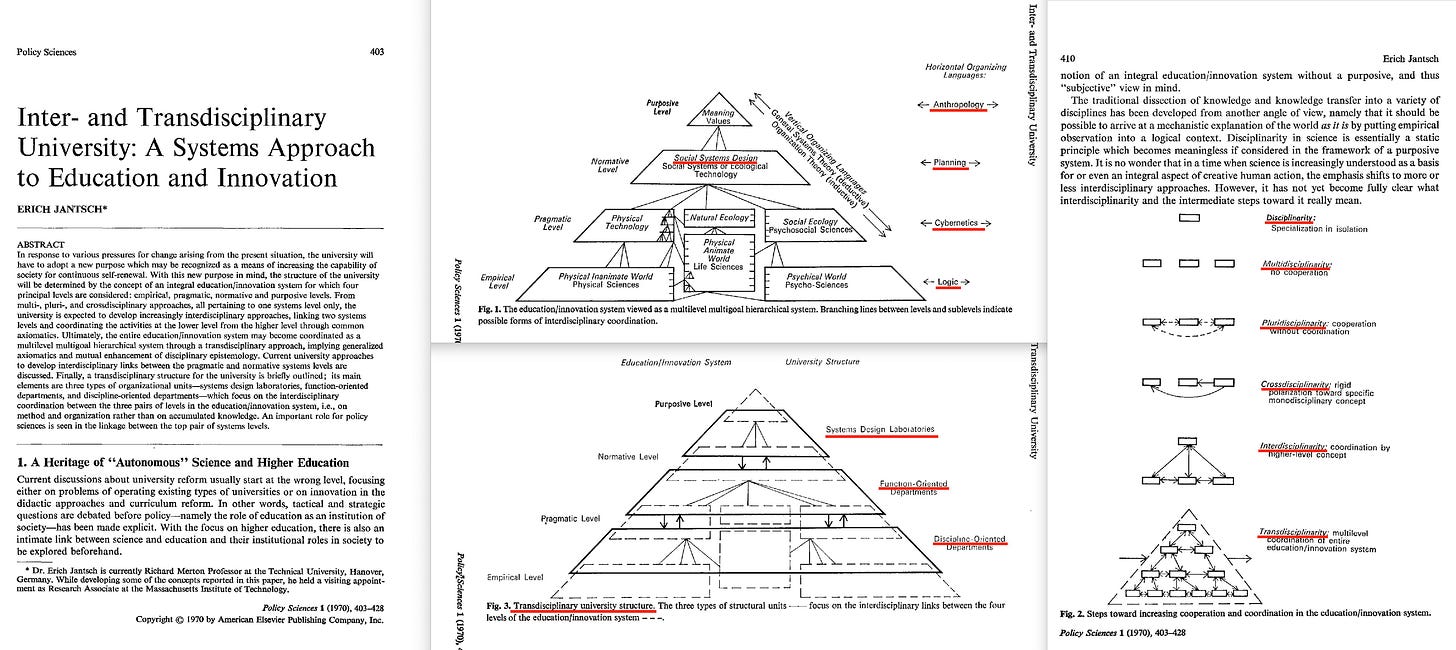

Thus, in brief, Tektology is a universal organisation science that bridges natural and social sciences, serving as a precursor to contemporary General Systems Theory, widely credited to Ludwig von Bertalanffy and Kenneth Boulding. And while the former described the world as a system of natural network topology, the latter structured it hierarchically, with each layer of organisational complexity resting upon the previous - culinating in life, human beings, social organisations, and, ultimately, transcendental systems featuring at the very top of this hierarchy.

And in 1970, Erich Jantsch integrated General Systems Theory with the Great Chain of Being, creating a four-level Inter- and Transdisciplinary University System Approach13 comprising the empirical (natural sciences), pragmatic (social science), normative (standards, codes, ethics), and the purposive (goals, objectives). And this hierarchical structure is centric to… really rather a lot going on at present.

But while General Systems Theory conceptually describes a hierarchical model, organising all matters relating to the geo- and biosphere, it does not describe flow in this system. And to this end, Bogdanov also devised Input-Output Analysis, though Wasily Leontief is typically credited with this invention. And IO analysis involves monitoring the system (generating surveillance data), which when combined with General Systems Theory modelling can then be used to forward predict flows. And in contemporary terms, this concept is known as dynamic systems modelling, described in a more popular term as… The Digital Twin.

Probably the easiest way to visualize this is through global supply chains, or the circulation of blood in your body. The arteries represent the system itself (as described through General Systems Theory), but these do not quantify flow. By monitoring flow through surveillance, the next step involves measuring circulatory feedback effects which can then be analysed and ultimately manipulated using principles from Norbert Weiner’s Cybernetics.

And there are two types of systems of interest - open systems, where no outer boundary exist, and closed systems, inclusive of boundaries - much like blood circulating your body, eventually returns to your heart. However, when we consider a closed system on a global scale… it just so happens that a such concept was popularised in the 1960s through Adlai Stephenson, Barbara Ward, Buckminster Fuller and Kenneth Boulding, through the idea of Spaceship Earth.

Planet Earth is not technically a closed system as it receives substantial inputs from especially the sun via sunlight, but in terms of natural resource management, it’s typically considered functionally closed, as no significant quantities of material are added (or removed). And this closed system - and the monitoring of specific, contextural resources - then take us to the next concept of the Circular Economy - which describes the monitoring of material flows in short supply (or even emission permits in the case of carbon-backed CBDCs, envisioned as ‘energy certificates’ by Technocracy Inc i 1936). But in context of Spaceship Earth, where IO analysis relies on continuously monitoring flows and stocks of material… this naturally creates a demand for global surveillance.

This ultimately leads to total control over the system, achieved through a process of Adaptive Management - a continuous, objective-seeking process that iteratively adjusts strategies based on feedback and forwards prediction through the Digital Twins. A process ultimately destined to become fully automated with time.

And this vision exactly… was remarkably described by Bogdanov long ago. Today, Adaptive Management systems are ubiquitous, embedded in everything from environmental policies to business operations, urban planning, and even digital platforms shaping the world around us - all in ways that closely aligns with Bogdanov's astonish foresight.

Adaptive Management is even used in context of Pandemic Planning.

And these conceptual systems form the foundational structure upon which the future geosphere management system (the Ecosystem Approach) rests, but we further have a parallel biosphere management system (the One Health Approach) seeking to integrate human, animal, and envirionment health. And thee two management systems then merge through Planetary Health, enabling a conceptual, comprehensive strategy for the real-time maintenance - and monitoring - of Planet Earth.

In other words - the Ecosystem Approach pertains to the geosphere, while One Health addresses the biosphere. And should we extend this framework to include the level above the biosphere - conceptually titled the noosphere by Vernadsky and Teilhard de Chardin - we arrive at Zev Naveh’s Total Human Ecosystem, encompassing all interconnected layers of Earth influenced by humanity.

The noosphere represents the collective sphere of human thought, a core component of which is… culture. And with that in mind, let’s return to Bogdanov.

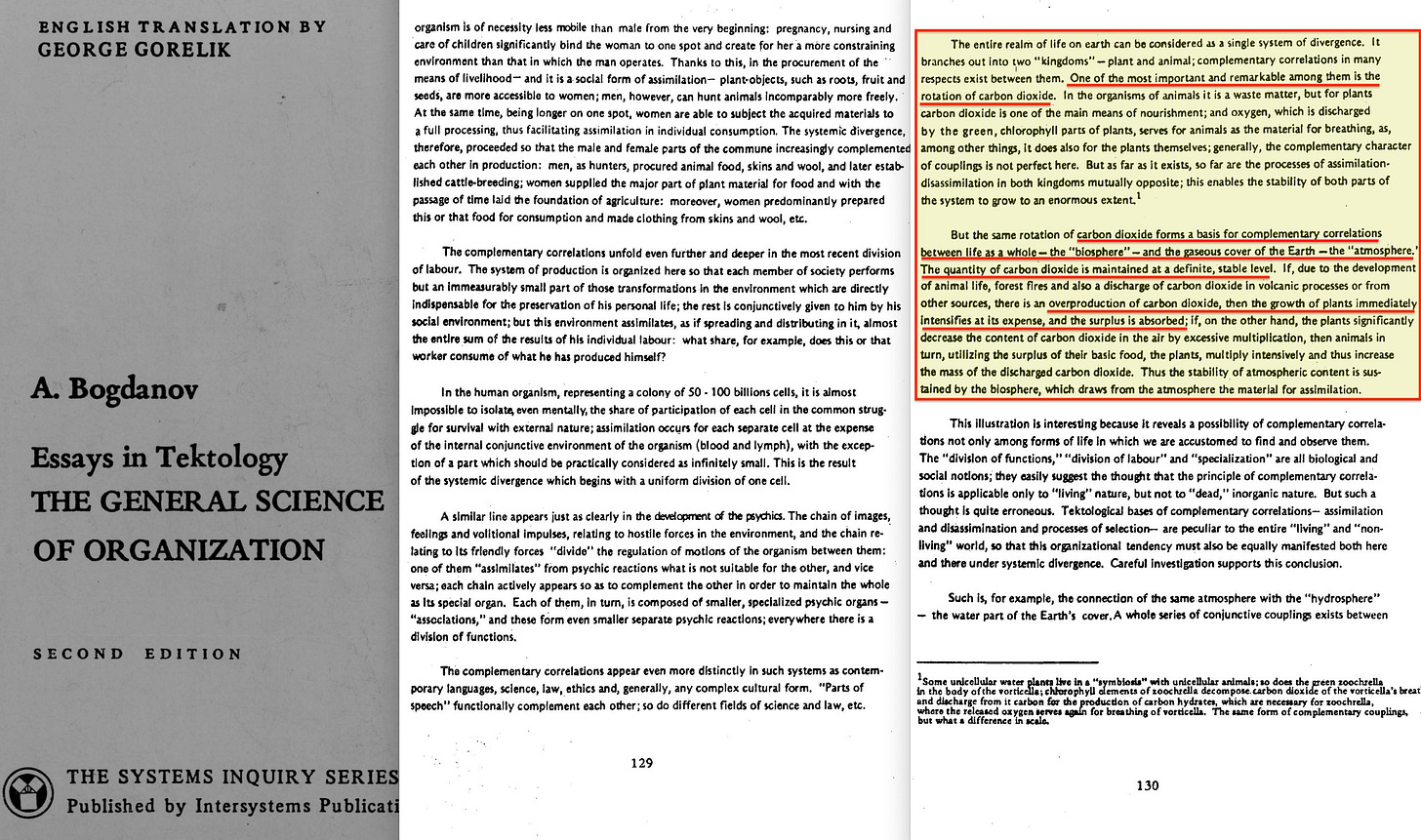

Bogdanov was a breathtaking genius. Of that there can be absolutely no doubt. Oh, you want another example? Well, how about the Gaia Hypothesis, which Milan Zeleny states Bogdanov formulated quite clearly.

But unlike the IPCC (and various other contemporary climate alarmists), Bogdanov amusingly realised that nature would absorb excess production of co2 through faster plant growth. Of course, when this did actually materialise, the information was that inconvenient to the narrative that NASA removed14 it off their website15.

Consequently, Bogdanov is responsible for -

Tektology; a universal organisational science which synthesises natural and social science, which serves as precursor to General Systems Theory modelling.

Input-Output Analysis; this deals with the circulatory flow in models outlined through principles of Tektology

Cybernetics; realising that closed systems would necessarily lead to feedback mechanisms, and as these can be monitored and ultimately utilised for sakes of control, these leads to principles aligned with those of Norberg Weiner.

Collective belief systems; with second-order principles relating to science now fused into the various disciplines, there is no longer a need for collective belief.

Culture; the way to direct society (and hence future society itself) would be through the manipulation of culture, where a primary focus would be on the science itself, using arts as a media for the communication of said.

Gaia Hypothesis; scaling of a closed system in context of carbon dioxide would eventually lead to a self-sustaining system on a planetary scale.

And he finally projected that future society would be fully automated, and ultimately structured much along the lines of what Technocracy Inc proposed… several decades down the line.

Progressively, science, arts, and politics were integrated through principles of Tektology - as outlined by Fabian Tompsett in 201616. And take away politics and you’re left with the World Academy of Arts and Science, or add philosophy and you have the Collegium International whose focus upon its founding in 1969 centred around General Systems Theory and Cybernetics17, seeking to apply science in the field of politics.

But while the Collegium International had not yet grasped the conceptual bridge between science and politics in 1969, by 2002 this path was well established - through ethics18… and the emergence of a world citizenry… human dignity.. responsibility towards future generations… reciprocity toward our fellow human beings… and an ethical quality to the democratic model.

In fact, in the 2002 call they even named themselves the…

INTERNATIONAL ETHICAL, POLITICAL AND SCIENTIFIC COLLEGIUM

Their 2003 ‘Declaration of Interdependence’19 followed, and besides calls for ‘democracy on a global scale’, ‘world public assets’, ‘indicators for sustainable development’ (normalised surveillance data), and ‘universalism of values’ (ethics), their list of first signatories included a great many notable systems thinkers, including -

Jürgen Habermas, whose theory of communicative action integrates systemic structures in social, cultural, and political contexts

Edgar Morin, one of the most prominent figures in systems theory, who emphasised ‘complex thought’ to understand interconnections across disciplines

Henri Atlan, a pioneer in self-organization and complexity science, foundational to systems theory applications in biology and beyond

Joseph Stiglitz, whose global economic frameworks incorporate systemic feedback mechanisms and interdependencies

Wolfgang Sachs, who applied systems thinking to the ecological, social, and economic dimensions of sustainability

Amartya Sen, whose ‘capabilities approach’ incorporates systemic thinking to holistically address societal progress

… and then there’s Michel Rocard, who not only co-founded the Collegium International, but also played a pivotal role in contemporary bioethics, originating in France, 1989.

In a more contemporary setting (2022), Örsan Senalp and Gerald Midgley’s paper ‘Alexander Bogdanov and the question of unity: An emerging research agenda‘20 goes that step further, calling for -

‘With our proposed research agenda, we argue that the exclusion of the first systematic work, the moment of emergence for the systems paradigm in the modern world, has constituted a serious boundary problem—especially for the efforts to unify the systems paradigm, as well as science. As in the general systemology project offered by Rousseau et al. (2018), or Mobus and Kalton's (2015) framework, systems scientists and systems thinkers continue to search for the universal first principle (or in Mobus and Kalton's case, 12 new principles) as well as a conceptual and methodological framework that could apply to the study of all reality, thereby allowing us to unite the fragmented paradigm of systems.‘

… further integration of principles of Tektology into all branches of science… an objective, EXPLICITLY envisioned by Bogdanov.

I personally always took Scientific Socialism as ‘Socialism via principles of Science’, as in, pure numbers, equations, and statistics in alignment with scientific monism. I never realised that it can be taken as a form of second-order Marxism, where principles and methodologies derived from Marxist theory are embedded into scientific, systemic, and institutional structures rather than being taught explicitly.

And this integration is particularly evident in fields like sociology through critical theory, economics through dependency theory, and systems theory in general. And common to this integration is an emphasis on systemic analysis, class relations, and societal contradiction - all without explicit Marxist labelling.

And all these fields, integrating said principles currently consider a comprehensive integration of the principles of Tektology, making the ‘skeleton of science’ consistent throughout. And that raises a final question… what about culture?

We previously saw how ‘Art, literature, philosophy and science‘ in short relates to the primacy of science, filtering through primarily arts. But there was no mention of the related centrality of education in this endeavour. And that’s where metacognition enters the frame, which relates to thinking about thinking and awareness and control of one’s own thought processes.

Or you can just go right ahead and relate it to ‘Systems Thinking 2.0’21. After all, the United States Army currently integrate just that22. Yes, really - we have arrived at the stage where even people themselves are considered ripe for subtle programming.

While Social-Emotional Learning relates to ‘what’, Systems Thinking 2.023 (DSRP; Distinctions, Systems, Relationships, and Perspectives) relates to ‘how’ - and both topics then relate to metacognitition - the field of thinking about thinking.

Cognitive systems science.

Yes, even cognitive sciences are now being targeted by the integration of principles relating to Systems Theory, and thus - Tektology.

One of the most astonishing things about the ICSU (ISC) is that they practically inserted themselves as the ‘S’ in UNESCO on their first day of operation24 back in 1946. And the individual responsible for just that was none other but Viktor Kovda.

And when the ICSU launched SCOPE in 1968-9, it was with Viktor Kovda in a senior position. And that in itself… is fairly damning. Why exactly did David Rockefeller travel to Moscow in 1964?

The ICSU voted to merge with the ISSC in 2017, thus fusing natural science with social science… thus aligning conceptually with General Systems Theory… which through C West Churchman’s ‘Systems Approach’ in 1968 further fused with… Ethics. In fact, Churchman’s approach went pretty close to the definition of Good Governance itself, which is established upon a foundation of… Ethics.

And Erich Jantsch’s 1970 paper (covered above) on the Inter- and Transdisciplinary University System Approach conceptually fused Churchman’s systems-driven approach with principles of Good Governance, emphasising adaptability and accountability. And this framework was founded on a hierarchical structure conceptually aligned with the Great Chain of Being, where the empirical (natural sciences; matter) were junior to the pragmatic (social sciences, organisation; soul), and with the normative sciences (ethics, codes, standards, codes; nous) above; ultimately all presided over by the purposive (goal, objective; the one).

And this hierarchical structure enables the setting of a purposive objective (ie, planetary health), derived normative ethics and standards (planetary ethics), which will then be converted into codified law and thus organisational legislation for sakes of… well, control of the people through weaponised ethics. And this is all currently taking place, per Gordon Brown, 2020.

As soon as the ink was dry on its establishment, the ICSU practically became the ‘S’ in UNESCO 1946, with Julian Huxley leaving to establish the IUCN in 1948. And in 1960, the World Academy of Arts and Sciences was launched by a number of convinced socialists - including UNESCO co-founder Joseph Needham - while the Collegium International saw its initial establishment only 9 years later.

And while the ICSU over the years has been trusted to fabricate the best scientific consensus available (at times through committees like SCOPE, who penned the early reports on the Global Environment Monitoring System), UNESCO integrated this science into education and culture, while the WAAS build the case for - amongst others -environmental science, and thus the IUCN in general.

And as the call for ‘ethics’ grew louder in the wake of the collapse of Enron, thus driving a call for business ethics, the Anthrax attacks driving a call for bioethics, and 9/11 driving a call for bioethics, the Collegium International returned in 2002, having solved the tricky issue of synthesising science with politics - through ethics.

And ethics serve as a foundational component of Bogdanov’s culture.

The silent influence of Alexander Bogdanov is absolutely undeniable. Not only did he through Tektology and IO Analysis create the foundation leading to the establishment of General Systems Theory and Cybernetics, which in turn facilitated the development of Global Surveillance Systems and the Digital Twin, both set in an environment of Adaptive Management, but his emphasis on the aspects of science and culture mirrors the pipeline introduced through ICSU and UNESCO, where the ‘best scientific consensus available’ leads straight to your kids’ curriculum, through the dissemination of said ‘science’ through education and culture.

And while we see progressive calls to integrate second-order Marxist principles into every strata of science materialise, one can’t help but wonder which other incredibly subversive contraptions he would have come up with, had it not been for that blood transfusion on that fateful day in 1928.

And in conclusion, let me link a few25 final26 documents27…..