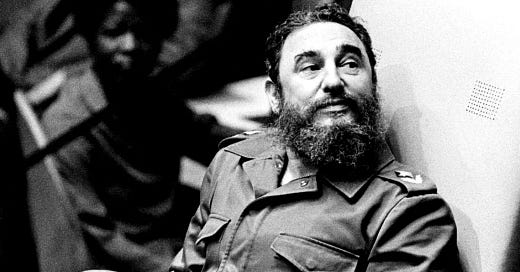

Launched on April 17, 1961, the Bay of Pigs invasion was a failed attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro’s communist regime in Cuba. The operation’s failure became an early embarrassment for President John F. Kennedy, prompting a swift restructuring of the intelligence community. This shake-up led to the forced resignations of CIA Director Allen Dulles, Deputy Director Charles Cabell, and Deputy Director for Plans Richard Bissell—the top tier of the Agency.

Yet a fourth casualty of this purge often flies under the radar.

This is a continuation of To Ourselves Be True, focusing on internal discussions around the creation of a World Congress for Freedom and Democracy—with Robert Amory Jr. in a leading role. Both he and Arthur Schlesinger Jr. backed the initiative, which in practice laid the groundwork for a structure that mirrored key principles of communism. It represented, in effect, a ‘Third Way’: a deliberate synthesis of communist and capitalist systems.

But there’s an issue—not only was Amory described as a personal friend of Kennedy, he was also allegedly unaware of the Bay of Pigs operation, according to both mainstream reporting and Arthur Schlesinger Jr. himself. Yet, as is often the case, a closer look at the details tells a very different story.

In late April 1962, Kennedy commissioned the Taylor Committee to investigate exactly what had transpired. The CIA withheld the report for years, with a second release attempt coming in 1984—still heavily redacted1. Yet even so, Chapter 6 leaves little doubt:

Recent declassification of the Executive Sessions of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee revealed that Amory certainly knew about the invasion plan by 11 January 1961 when he accompanied DCI Dulles to Dulles's off the record briefing of the Committee.

And around the same time:

Also in late January 1961 at the request of Director Dulles, Kent's Office of National Estimates prepared an internal memorandurn on ‘Probable International Reactions to Certain Possible US Courses of Action against the Castro Regime’. One of those courses of US action was to "provide active support of varying degrees of magnitude and overtness, to an attempt by Cuban opposition elements, internal and in exile, to overthrow Castro." As with both DDS White and DDI Amory, Kent was a participant in the DCIls morning meetings; …

There’s no ambiguity here—Amory knew.

The full release of the Taylor Report came in 20162. And volume 3 adds another key detail3:

… the Director of Central Intelligence also was required to make a presentation before the CIA Subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee on 6 January of 1961… Mr. Dulles discussed the radio effort and paramilitary effort in some detail, indicating the numbers of Cubans being trained and the supply efforts and the bases.

And as for Amory—and Schlesinger:

Because of the subsequent charges which would be made by historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. and others writing on the Bay of Pigs, it is important to emphasize that among other CIA personnel attending this briefing was Robert Amory, Jr., the Deputy Director for Intelligence, who, according to Schlesinger and some of the later ‘experts’, was supposed to be in almost total ignorance of any planning for an operation such as took place at the Bay of Pigs.

Amory knew. And Schlesinger lied.

Amory also held a notably conciliatory stance toward the Soviet Union. In 1959, he predicted that the Soviets would ultimately back down over Berlin4. A year later, in 1960, he stated that no major changes were expected within the CIA5. Then in 1961, conservative radio broadcaster Fulton Lewis Jr.—best known for being among the first to expose Julius and Ethel Rosenberg as Soviet spies, later confirmed by the Venona papers—publicly labeled Amory a hyper-liberal. He also revealed that Amory had donated to the legal defense fund of convicted Soviet spy Alger Hiss6.

In the previous post, we covered two core documents: Proposal for the Creation of a World Congress (22 August 1961) and A Declaration of Principles (3 October 1961). But there’s a third—linked to the Paris conference referenced in Amory’s report dated 22 January 19627.

This third document anticipates political and ideological challenges the initiative might face. It explicitly ties the Congress to Walter Lippmann’s Public Philosophy and frames the World Congress for Freedom and Democracy as a public-private enterprise. Crucially, it is to be funded by governments—with no strings attached—on the grounds that ‘otherwise foundations might not want to contribute’. Complete independence is emphasized, lest ‘the communists play upon the suspicion of government control’.

The document is steeped in familiar collectivist language, though it makes an effort to deflect concerns that the Congress could become a ‘state within a state’ or violate the Logan Act. And next, it includes terms which should be familiar:

Nationalist or isolationist elements might denounce the cosmopolitanism, the ‘One World’ tendency of the institution.

The Congress was envisioned as a ‘mixed effort’ designed to counter the ‘dualistic organization of the communist challenge’. Or as the document puts it:

Our proposal is for the creation of a sort of quintessence, an intepeneration of constituted, and free civic organisation on a world scale without resort to that basic element of Communist dynamics, the dictatorship of a revolutionary elite.

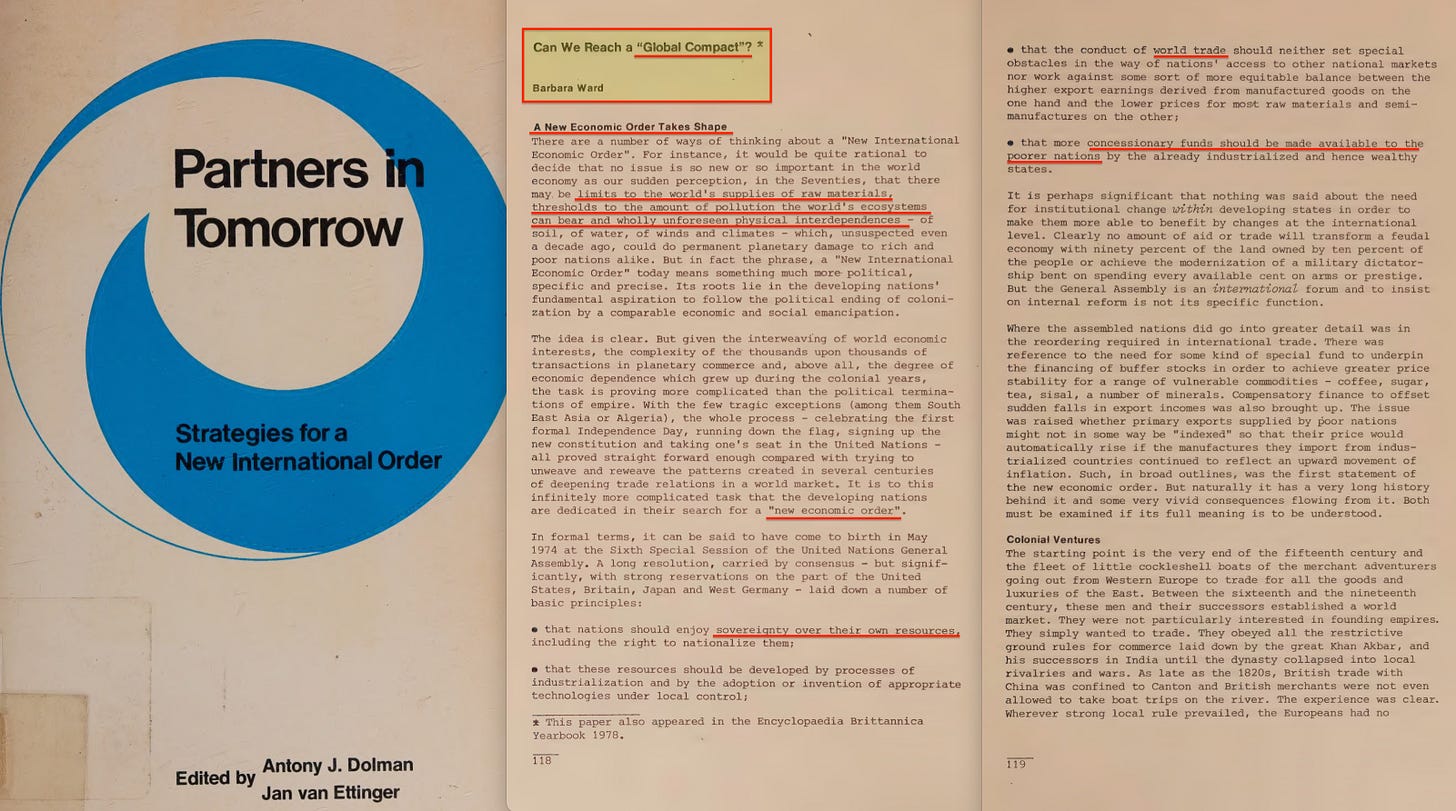

This model of civic participation would later accelerate through the IFDA’s Third System project in the 1970s8—an initiative Maurice Strong directly supported. It was through this effort that the Partners of Tomorrow document first called for a “Global Compact,” with the idea championed by Barbara Ward, best known for her Spaceship Earth vision.

Incidentally, the IFDA9 was also the first to use the term sustainable development. While the 1987 Brundtland Report is commonly credited in the public sphere, the 1980 World Conservation Strategy by the IUCN actually predates it. However, internal IFDA documents had already referenced sustainable development as early as 197910—marking the true origin of the term within policy circles.

Either way, the vision of a ‘free civic organisation on a world scale‘ ultimately materialised as what we now call Civil Society Organisations (CSOs). Today, these entities through Trisectoral Networks play a central role in driving decision-making processes at the United Nations.

Here’s another example from 197911.

The document further specifies that the Congress should ‘exclude only the anti-Democratic extremes’—which, as noted in the first post, did not include scientists from behind the Iron Curtain. It then goes even further, advocating participation from:

The answer is that the World Congress would bid for the participation of political parties on the same basis as that of states, …

Political parties. And as for any claims of avoiding elitist structures:

As we have indicated, the succeess of this endeavor would depend on the ability of the Congress to combine universality of principle with particularity of action. It would have to create a new kind of international career service, a body of dedicated men, patterned, one might say on the exemplar of Dag Hammarskjold, who are citizens both of their native countries and of the world.

In other words, the World Congress would rely on a specially educated, quasi-civil service class to administer the project—a textbook definition of elitism, dressed in internationalist language.

As noted in the first post, while the Congress claims to uphold Western ideals, the issues it chooses to address tell a different story. The document makes clear:

If the Congress is not to become a factory for pious platitudes, it will have to address itself squarely to burning, explosive issues, such as apartheid, expropriation or nationalization of property, and political self-determination.

And when specific examples are given, their focus gravitates—almost magnetically—toward Western nations:

Criticism of governments which are seeking an evolutionary, rather than a revolutionary solution to such problems - for example, the United States with regard to Negroes…

This, incidentally, is exactly how Jeffrey Sachs frames his arguments.

The ideological bias is clear. And the language soon becomes even more familiar:

By its close contact with all public and private entities significantly concerned with matters of freedom and Democracy the staff should perform the function of a catalyst. Without fear or subjection to pressure, it should seek to bring together opposing parties, lobbies, interest groups and even officials of State in constructive clash of views, and to create its own methods of synthesizing their dialectic.

The World Congress... bringing together public and private entities, lobbies, and interest groups? That’s civil society—non-governmental organizations—in all but name.

Then follows the predictable nod to Walter Lippmann:

The word ‘ideology’ has been avoided in the Proposal and the Declaration, with preference to ‘theory’ or ‘doctrine’, where these are in question, and such terms as Walter Lippmann's ‘Public Philosophy’

Followed swiftly by the philosophical sleight of hand:

… there can be no Orwellian ‘newspeak’ in the lexicon of the Congress… It will not do to say that our Democracy is true Democracy because our Freedom is true Freedom. We must establish absolute categories of judgment which can be applied to every concrete instance.

Which, of course, directly echoes Lippmann’s own call for a new public philosophy grounded in fixed moral categories.

Then comes the collectivist kernel—thinly veiled in the language of democratic education:

We have sought to meet this problem squarely in affirming that education is prerequisite to the attainment of true Freedom. A literate, and, as the Communists say, a ‘conscious’ electorate alone can exercise civic functions in the spirit of respect for the worth of the individual and resolve the dialectic of his personal conflict with the interests of the collective, the community and the state.

At this point, the ideological convergence is undeniable. This is collectivism, plain and simple. The language, the goals, the dialectic—it’s all there.

Education opens the gates to material progress, and permits the orderly construction of the fabric of economic well-being, without which, as the Greeks discovered, Man is not free but enslaved.

No, really.

I could carry on with more examples, but is there a point?

We have sketched in the Declaration a concept of the ‘nature of the era’, dynamic in essence and optimistic in tone. There is abundant evidence that the Free World is reaching out for such a concept, and will grasp it if it is presented in credible terms. Leaders and led, intellectuals and simple workers, daily express in a thousand ways the craving for positive beliefs and programs of action…

And then the key question:

Can the theme of ‘Revolution’ be woven into the program of the Congress?

The message, it seems, must be crafted simply—so even the ‘simple worker’ can understand the need for a heightened tempo of evolution.

Well then. How about this12?

Working Men of All Countries, Unite!

Once again, the nationalist is cast as the boogeyman—the regressive force standing in the way of World Federalism. Without such integration, we’re warned, we’re left with ‘a world order of atomistic nations’.

To that end, the document states:

We have suggested in the Proposal that the Congress cannot at least at the outset, espouse existing federalist causes. It can, however, address itself promptly to the study of them, and to the encouragement of a rational effort to move forward into the age where regional groupings, far broader than existing territorial sovereignties, will inevitably take shape.

Make no mistake—they are calling for World Federation13. And such a drive does not align with individualism or sovereign self-determination, which tends to reject the very premise of, the very descriptive term that is ‘atomistic nations’.

What follows is the predictable demonisation of anything that stands outside the internationalist consensus.

To communists, up is down, and slavery is freedom:

… authoritarian and restricted systems to possess advantages of order, discipline and stability, whereas Democracy often detertorates into demagogy, mob rule or civil strife - ‘stasis’…

It’s shameless. The reason such ‘order’ exists, of course, is the brutal suppression of dissent under authoritarian regimes. But that detail is conveniently ignored. Instead, the document continues:

These tendencies may even be accentuated in modern times with the spread of mass media of communication, readily subverted to totalitarian purposes... Even where elections were technically ‘free’, they often have been rigged and manipulated.

Thus, the argument is: democracy is inherently untrustworthy because it can be subverted. Therefore, a democracy that’s already been subverted is preferable, because it cannot be further corrupted.

And the conclusion?

The concept of a ‘guided democracy’ is not necessarily a mere facade for personal tyranny, but may correspond to the needs of political evolution in an intermediate stage.

This is a thinly veiled call for International Government—precisely what the Fabian Society and Leonard Woolf outlined in 1916. What they termed International Government, the World Congress now rebrands as Economic Democracy..

The remainder of the document largely echoes the themes already discussed in the first post—except for one final, major topic of concern:

Can the ‘population explosion’ be checked in time to realize the ‘fullness of the Earth?’

Malthusianism, in short.

The document then offers a qualified admission:

… the earth can nurture and sustain far more people than now inhabit it. Over a period of time, this proposition is certainly true, but not necessarily in the short run.

And on that basis, it calls for:

prudent curtailment of man's fertility… committing a life to this planet is a social responsibility

This aligns closely with the Rockefeller Foundation’s simultaneous push for population control14—an agenda they had been advancing for decades15. The call goes beyond access to contraception or support for planned parenthood; it enters the realm of ethics, with population planning framed as a moral imperative:

Has the Free World the moral strength to meet the challenge of Communism? Through its dedicated opposition to all the forces which work against the dignity of man the Congress could become an arbiter in matters of public morality.

Before closing, the document reiterates the need for a public-private partnership—driven by civil society organizations working toward a collective vision of the common good.

Amory promoted this vision—of that, there can be no doubt. His involvement is clearly evidenced by two internal memos dated November 17 and November 20, 196116. Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. was fully aligned with the initiative as well. And, as we’ve already seen, Schlesinger later misrepresented Amory’s knowledge of the Bay of Pigs invasion—deliberately so.

Robert Amory’s final day at the CIA was April 15, 1962. The very next day, Deputy Director Marshall Carter formally rejected his appeal regarding the World Congress for Freedom and Democracy. That timing appears strategic. By issuing the rejection after Amory’s termination, it effectively foreclosed any possibility of further appeal.

Likewise, Arthur Schlesinger’s false claims about Amory’s ignorance of the Bay of Pigs operation seem equally calculated. With the rest of the CIA’s senior leadership removed, Amory had been the last figure positioned to push the World Congress initiative forward. His removal closed the door on that effort—at least temporarily.

As for the oft-repeated claims of friendship between Kennedy and Amory, one document puts those to rest. A Department of Justice memo dated February 11, 1963, offers a very different picture. It reveals that Amory was suspected of passing information to Yugoslav intelligence. The matter was brought directly to President Kennedy—who, notably, took personal interest and authorized technical surveillance of Amory’s private residence17.

John F. Kennedy had Amory’s home bugged, in short.

The memo goes further:

Amory has been a controversial figure. The Director has stated we should be circumspect in dealing with him. His interpretation of world communism has been questioned by a responsible army official.

And:

He allegedly advocated admission of Red China to United Nations, discontinuance of CIA covert operations and opined that the cold war policies of noncommunist countries prevented Soviets from being reasonable.

Not to mention his recommendation for the creation of a World Congress—an initiative whose structural and ideological design closely echoed the aims of the Comintern.

And that’s where a secondary issue arises—one that’s easy to overlook. If Kennedy truly took a personal interest in Amory’s case, it’s hard to imagine that Amory’s policy initiatives and internal memos wouldn’t have come under close scrutiny. And once reviewed, the proposal for a World Congress—so clearly aligned with collectivist, even Comintern-style ideals—would almost certainly have raised red flags.

In that sense, Amory’s termination didn’t just remove a dissident voice. It effectively killed Plan A. Because even if the Congress had gone ahead, it would have faced immediate and ongoing oversight—by the FBI, by the DOJ, by the press. The initiative could no longer move forward in the shadows.

Robert Amory also fully defended the CIA’s use of dummy foundations to funnel funding to preferred organisations18. When Barry Goldwater later exposed that some of these funds had gone on to finance socialist causes19, Amory argued that the real issue wasn’t the funding itself—but the fact that it had been exposed. That stance, of course, isn’t surprising given his broader record of appeasement—not only toward the Soviet Union, but also toward Communist China, which he had advocated admitting to the United Nations early on20.

The internal memo, despite its ‘devil’s advocate’ framing, reads less like a critique and more like a blueprint. It outlines a mechanism structurally indistinguishable from Lenin’s New Economic Policy—the very model it claims to resist. A private-public hybrid, funded by states but shielded from oversight, administered by an international elite specifically trained for the role, and structured to serve as a moral and ideological regulator at the global level. This was not simply a diplomatic forum; it was conceived as a civilisational engine—reordering norms, wealth flows, and public philosophy while bypassing traditional democratic accountability.

Its language is unmistakable. Terms like ‘dialectic’, ‘restitution’, and ‘guided democracy’ signal a clear philosophical convergence with Marxist systems theory. The Congress is tasked with synthesising opposing political forces, resolving the individual’s conflict with the collective, and shaping a new civic consciousness—one that aligns disturbingly well with the internal mechanisms of communist governance. Even the proposal’s approach to education, morality, and population policy borrows directly from central planning logic, couching collectivist ideals in Western liberal vocabulary. It envisions a permanent apparatus—’a universal lobby’—to coordinate global governance through overlapping institutions, lobbies, and elite-managed conflict resolution.

Amory, for his part, not only endorsed but helped construct this framework. His memos in November 1961 show his deep investment in the project’s philosophical and institutional foundations. Schlesinger’s later denial of his involvement in Bay of Pigs planning appears, in hindsight, as strategic obfuscation—shielding Amory from association with an operational failure so that he could continue pushing forward the Congress initiative while the rest of the CIA leadership was purged. But Kennedy’s personal surveillance order suggests that the White House was already aware that this wasn’t just about foreign policy—it was about ideology.

Amory’s final appeal to move the World Congress forward was met with calculated silence—until April 16, 1962, the very day he officially departed the CIA. Only then did Deputy Director Marshall Carter respond with a formal rejection. The timing ensured Amory had no avenue to challenge the decision—his voice was removed, and with it, Plan A was buried. But the underlying agenda did not vanish. What followed was a pivot to Plan B—a more diffuse, indirect strategy centered on NGO-driven civil society as the vehicle for global governance. Yet there was a problem: Kennedy.

By early 1963, JFK had grown deeply suspicious. On February 11, he personally requested that the FBI place Amory under surveillance—suggesting he had not only seen through the façade but also understood the deeper implications. And that posed a fatal obstacle. If Kennedy had already dismantled the World Congress pipeline and was now targeting its ideological architect, no Third System initiative—let alone a broader civil society capture—would be safe under his administration.

For Plan B to proceed, Kennedy had to go. This wasn’t just about institutional adaptation; it was about regime change.

The vision that had been mapped out—civil society as a parallel governance system, operated through supranational networks and insulated from electoral accountability—could not advance while JFK remained in power.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The price of freedom is eternal vigilance. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.