Science and Ethics

‘Science is concerned with what a man (or, a thing) must do, ethics with what he thinks he should do. Until the contrary is proved, therefore, we must suppose ethics to be derivable from science.‘ —JBS Haldane.

I have noticed that posts on the topic of ethics don’t tend to be particularly popular. And though I understand that it doesn’t appear to be a terribly exciting topic, the reality is that it’s quite possibly the most important of them all. And that’s no exaggeration, as my colossal, combined synthesis places ethics squarely at the centre of everything.

Ethics turns science into an imperative. It acts as a guiding force. It is used to subtly programme moral values into collective society through education, culture, media, and even religion. And it also serves as the conduit for legislation.

This, in turn, makes it incredibly dangerous because it is a well-trodden path. Hitler, Stalin, Mussolini, Pol Pot—all fused ethics with legislation, with disastrous results.

In yesterday’s article on Science and World Order, we saw how the collective British scientific leadership in 1941 overwhelmingly supported Marxist socialism, with central planning as the key objective. And to prove that this wasn’t a coincidence, here’s J.G. Crowther1, one of the primary contributors.

Of other pivotal figures contributing to that report, we have JBS Haldane2…

… Joseph Needham3…

… and JD Bernal4 - all of whom were outright Marxists. When I call someone a Marxist, it’s because I typically have a damn good reason to do so. And the link to CP Snow is of further interest, as it was he who launched the ‘Two Cultures’ spat.

Yet another figure involved in the 1941 event was Julian Huxley, co-founder of the IUCN (along with many other institutions, including UNESCO). And while you’d be hard-pressed to find direct evidence of this particular Fabian Socialist being an outright Marxist, he might as well have been. Furthermore, he was a key member of the Fabian Society inspired Political and Economic Planning5 Committee, alongside WWF co-founder Max Nicholson.

Yet another organisation co-founded by Julian Huxley was the International Humanist and Ethical Union, now known as Humanists International. Their present webpage is quite explicit about its purpose—this is about scientific rationality and the ethics derived from it. The British counterpart, in its early days, was run by a certain Susan6 Stebbing7.

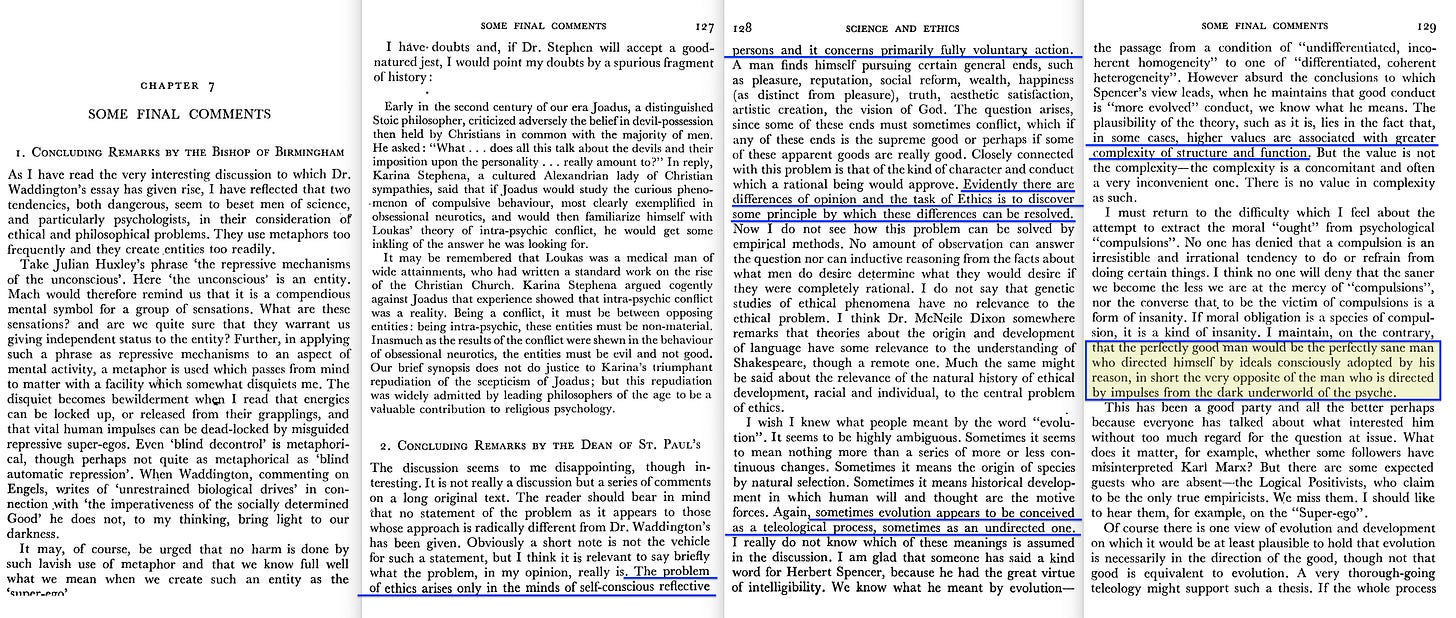

And Stebbing, along with Haldane, Needham, Bernal, and Huxley, all contributed to today’s report from 1942, titled Science and Ethics. In fact, I took the liberty of underscoring Marxists, socialists, Fabians, and environmentalists in said report, and… well, apart from clergymen who have to stay impartial, it’s pretty conclusive. This follow-up — further contributed to by Miriam Rothschild, who was also present at the founding of Huxley’s IUCN — was yet another hard-left production, featuring a line-up strikingly similar to Science and World Order.

And the purpose of said report?

‘… to find an intellectual basis for ethics…‘

But, as said, the topic of ethics doesn’t tend to be the most popular. But as I don’t typically go by popularity alone — especially when a topic is of critical importance — I persisted. But rather than linking later on, let me include just some (there are more) of these posts here, so you can scroll past them in one go instead of encountering them separately. And all of these, fundamentally, place global ethics at the very centre of what is happening today.

With all of that said, let’s get on with the show, starting with the most clear-cut paper of the lot—J.D. Bernal’s A Marxist Critique. And he begins by defining objective Good as the Direction of Evolution. And that is… simply remarkable, as it completely aligns with Darwin’s bulldog, T.H. Huxley, who, in an 1893 lecture titled ‘Evolution and Ethics’8, spoke of humanity taking control from nature and guiding evolution, but also with Teilhard, who said much the same. In fact, Teilhard’s most famous book, ‘The Phenomenon of Man’ even featured a foreword by TH’s grandson - Julian Huxley9.

Either way, Bernal continues by stating that we know where we’ve been, and we know our present state — but the future presents somewhat more of a difficulty. And the issue of the past was not so much the Church itself, but that the Church was embedded within the scientists themselves. Ergo, they had to separate themselves from religious morality and adhere to Marxist philosophy.

But fundamental to all of this is the dual nature of fact and value. And while this division is still considered sharp, the relationship between science and ethics is seen as definite, yet limited. However, while scientific knowledge provides precisely the means necessary to achieve things deemed good, science itself does not determine what can be considered good.

A new and unified conception of ethics can only emerge if we abandon religious morality (and learn to embrace Marxism). This should fundamentally relate to ethical standards derived from present-day experience and scientific discovery, projected in the direction of evolution. Any appeal to external standards of ethics is nothing short of intellectually empty.

Bernal further explains that ethics isn’t something separate from life—it’s something people absorb from birth, shaped by family, school, and society. The ethics people follow today still carry pieces of older systems, built for past societies and economies. But just because old ideas about ethics fade doesn’t mean people will lose their sense of right and wrong. And that’s a positive, as ethics becomes even more important as the world becomes more connected.

Science, he argues, doesn’t exist to decide what is ‘absolutely good’ or to serve religious ideas about eternal values. Instead, its role is to study and understand society as it changes, helping people act in ways that work best for everyone — somewhat reminiscent of collectivism. He further considers the giving of more control over their environment to people was the first big contribution of science to society. But now, things are at a turning point. Social structures have become so powerful that conflicts are starting to undo progress, even threatening people’s survival. The only way to prevent disaster is to understand how societies and economies work—and that, Bernal insists, is now science’s job, especially one for the social sciences.

He points to the Soviet Union as proof that theory and practice must go together. This, he says, is where ethics truly changes. It isn’t some separate thing, floating above real life. It isn’t about chasing an idea of ‘the Good’. Instead, it’s about fully understanding the world and actively working to change it. Yet, ethics will always have a personal element, because each person’s role depends on their knowledge and experiences.

According to Bernal, the world is in the middle of a massive transition. A new society is forming inside the old one. When it takes over, it will bring new ethics along with it. Some old values will disappear, while others will grow stronger. Ideas about fairness—social, economic, and political—will become the most important, and in place of self-interest and strict loyalty to family, society will value responsibility and cooperation. The idea of absolute values, like unchanging moral truths, will be considered just as false as the idea that knowledge can exist without experience. Ethics, as something created by human society, will always evolve.

Ergo, what Bernal outlines here is that the direction of evolution should be guided through ethics—essentially the same argument presented by T.H. Huxley in 1893.

The first paper in the report to which everyone is responding is titled The Relations between Science and Ethics… but it’s not particularly interesting and is mainly included here for sakes of completeness. The most important argument on the first few pages is probably this:

‘In the first place, ethics appears among psycho-analytical phenomena as the consciously formulated part of a much larger system of compulsions and prohibitions.‘

And this explores whether ethical beliefs come from outside influences—implanted into individuals independently of their experience—or whether they develop through personal interaction with the material world. Because rather than being fixed rules imposed from above, ethics could instead be shaped by how people engage with their surroundings.

However, the argument goes even further. Ethics, at this stage, is seen as a set of rules necessary for society to function. In this sense, ethics serves a primarily conservative role—it exists to maintain order and ensure stability rather than to challenge or reshape the structure of society.

Waddington then contrasts the two views on ethics and evolution. T.H. Huxley argued that ethical progress requires resisting nature’s brutal survival mechanisms, rather than imitating or avoiding them. He saw the natural world as governed by a gladiatorial theory of existence, where the strongest dominate through ruthless self-assertion. But Waddington, however, defines ethical principles as psychological compulsions shaped by society. Since societies develop in particular directions, the ethical values that emerge are those that support this movement. In this sense, ethics aligns with the process of social evolution rather than opposing it.

On a broader scale, he argues that what is considered ‘good’ is simply what has been effective—what has shaped evolution itself. This leads to his conclusion that science plays a direct role in ethics. Since ethics is grounded in real-world facts, science can reveal the nature and direction of evolution, helping society understand the consequences of different actions and guiding ethical decisions accordingly.

Consequently, what Waddington here argues is that science can be used to guide ethical principles.

Next follows Julian Huxley, who discusses how science can lead to new ethical approaches, particularly in areas like public health. Scientific understanding has introduced moral duties related to hygiene, disease prevention, and social responsibility in controlling infections—duties that were not previously recognised.

He argues that ethical development involves moving away from rigid, absolute moral rules and instead adapting them based on reason and experience. Over time, categorical imperatives lose their strictness, and their focus shifts to align with new knowledge and societal needs.

Huxley acknowledges Waddington’s observation that ethical systems vary greatly between societies, often contradicting one another. This pattern is also seen in the evolution of cultures, suggesting that ethics is not fixed but continually reshaped by external influences. He ultimately supports Waddington’s view that ethical systems act as essential social mechanisms.

Ethics emerges from the interaction between individuals and the changing world, shaped by social conditions while also influencing those conditions in return.

This leads J.B.S. Haldane to suggest that a deeper understanding of Marxist literature could have given Waddington more insight into the connection between unconscious motivation and ethics. He points out that Engels had already emphasized unconscious motivation before Freud, highlighting the role of underlying social and historical forces in shaping human behavior.

Haldane then connects this to T.H. Huxley’s argument in Evolution and Ethics, interpreting it through a dialectical lens. He explains that the cosmic process, which led to human evolution, ultimately negates itself by giving rise to ethics. In other words, the very forces that shaped human survival now create moral systems that counteract the harsh logic of natural selection. This creates a dilemma: if ethics prevents the elimination of the weak, how does human evolution continue?

Haldane then argues that science and ethics are fundamentally connected. Science deals with what must be done, while ethics concerns what people believe they should do. Since ethical beliefs are shaped by human understanding of the world, and science provides the most reliable understanding, ethics must ultimately be derived from science—unless proven otherwise.

He further claims that science has always achieved universal agreement at different levels of analysis. Unlike past ethical systems, which have varied widely across cultures and failed to create universal moral principles, science consistently establishes shared truths. Because of this, he asserts that science must serve as the foundation for future ethics, providing a universal system that humanity has so far been unable to achieve.

Ie, what Haldane is actually suggesting here is the creation of a Universal Moral Framework — essentially, a global ethic — from the pursuit of scientific reason.

Joseph Needham follows, arguing that human cooperation and social solidarity are direct products of evolution. He refers to Henry Drummond, who claimed that evolution’s ultimate goal was love and the good life—a statement dismissed as ‘grotesque’ by his biographer. However, Needham defends this idea, suggesting that if human social structures are a result of evolution, then concepts like love and ethical behavior must also be part of that process.

He aligns this view with Waddington’s argument that evolution itself provides a criterion for defining ‘the good’. In this framework, what is considered good is simply what strengthens social cohesion among highly organized beings like humans.

Taking this further, Needham draws a parallel between human relationships and fundamental physical forces. He suggests that the bonds of love and camaraderie in society function similarly to the forces that hold particles together at molecular and even subatomic levels. From this perspective, ethical principles are not abstract ideals but natural extensions of the evolutionary process.

Ultimately, he concludes that the concept of ‘the good’ does not exist in nature at lower levels of complexity. It only emerges when evolution reaches the human stage, reinforcing the idea that morality is deeply tied to social and biological development.

Next follows a back-and-forth, which can broadly be summarised as such -

Science provides the means to achieve a goal but does not determine what goals should be pursued. This highlights a fundamental challenge in ethics—deciding what ends are truly desirable.

Ethics, by its nature, is forward-looking. It is concerned with shaping the future rather than being bound by past traditions or inherited moral frameworks.

Ie, it’s evolutionary. Evolutionary Ethics. Thus, we’re back with TH Huxley in 1893.

And through the conclusion, we find that evolution is sometimes viewed as having a purposeful direction, while at other times, it is seen as random and undirected. Ie, semi-teleological evolutionary ethics.

And further it is claimed that a truly good person would not be guided by unconscious impulses but by reason and consciously chosen ideals. Thus, rational self-direction, rather than instinctive or subconscious drives, defines true moral character.

Ie, a good person is a rational person, guided by a Universal Moral Framework.

And just as a healthy body functions smoothly to sustain life, a good person is one whose actions not only support their own well-being but also contribute to the strength and stability of their social group. Ethical behavior is not just about personal morality—it plays a crucial role in ensuring that societies remain functional, cooperative, and capable of progress.

And this connection between science and ethics was further a topic of discussion at the 1940 symposium of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, reflecting the growing recognition that moral systems must be examined through a rational and empirical lens.

Ultimately, the survival of individuals, groups, and even entire species depends on their ability to adapt and live harmoniously with one another and with their environment. The more effectively people adjust to social and ecological realities, the greater their chances of long-term success. Ethics, in this sense, is not merely an abstract concept—it is an essential mechanism for ensuring cooperation, resilience, and continued human progress.

Consequently, ethics is not just a set of abstract principles—it functions as a mechanism that enables human society to function and evolve. By establishing moral systems, humanity has been able to organise itself, ensuring cooperation and stability while also providing the motivation for further evolutionary progress. Ethical frameworks are not separate from the evolutionary process; rather, they have actively shaped it, guiding the development of human civilization.

And because ethics has played such a crucial role in human evolution, it becomes possible to define a universal ethical system—one that has already proven effective in directing human progress. Instead of relying on subjective interpretations or cultural traditions, this system can be deduced from the very nature of the evolutionary changes it has produced. In other words, the ethical principles that have consistently contributed to humanity’s survival and advancement form the foundation of an ethics applicable to all of mankind.

And science, as the discipline concerned with uncovering truths about the world, is in a unique position to contribute to ethics. Since ethical systems emerge from observable patterns in human behavior and social structures, science can help identify the trajectory of human evolution and assess the consequences of different ethical choices. Rather than treating ethics as a subjective or purely philosophical matter, science provides a method for analyzing and refining moral systems based on their impact on human progress.

This perspective carries serious implications. If ethical systems are understood as key variables in human evolution, then harmful or destructive moral frameworks can be compared to deleterious genetic mutations—damaging the social organism rather than supporting its survival. Just as biological evolution selects against harmful traits, a rational approach to ethics would involve recognizing and discarding moral systems that hinder human development, encourage conflict, or obstruct societal progress.

Thus, by framing ethics within the context of scientific analysis and evolutionary direction, humanity can move beyond outdated moral traditions and towards an adaptive ethical system—one that is rooted in reason, effectiveness, and long-term survival.

Ethics can further be understood on multiple levels—individual, communal, and civilizational. While personal morality governs individual choices and social ethics shape interactions within communities, macro-ethics operates on a much larger scale. It is concerned with the values that guide the progress of humanity as a whole, shaping the long-term direction of civilization.

This broader ethical framework is not about isolated moral decisions but rather about structuring society in a way that promotes the survival, advancement, and flourishing of the human species. It includes questions of governance, scientific responsibility, environmental stewardship, technological development, and even the moral imperatives that drive human evolution itself. In this sense, macro-ethics serves as the foundation for decisions that affect entire generations, cultures, and the future trajectory of human civilization.

By focusing on macro-ethics, the discussion moves beyond individual moral dilemmas and cultural traditions, instead seeking universal ethical principles that can guide humanity toward sustainable progress, an approach particularly relevant in an era where global challenges require collective action and long-term strategic thinking.

Ultimately, the study of macro-ethics is about more than just understanding past ethical frameworks; it is about shaping a forward-looking ethical system that aligns with scientific progress, social cohesion, and the continued evolution of human society. It is the ethical foundation upon which the future of civilization must be built.

In short, TH Huxley’s 1893 lecture was remarkably accurate. Evolutionary Ethics can, and should, be used as a teleological force. So with that in mind, let’s step to 1938, and an article titled ‘Science and Ethics‘, published in Nature, penned by Dr. Edwin Grant Conklin10, which goes on to state that the relationship between science and ethics is often framed as a question of compatibility—can science inform morality, or should ethics remain separate from empirical knowledge? But the argument put forth insists that ethics must evolve alongside science if human progress is to be truly meaningful. A purely mechanistic view of the universe, in which human actions are dictated solely by biology or environment, strips individuals of moral responsibility and the ability to choose between alternatives. Instead, ethics must be seen as a rational, evolving process—one that is not dictated by natural selection but shaped by intelligence, reason, and social cooperation. And that yet again places T.H. Huxley’s Romanes Address (1893) as central to this discussion, as he directly opposed the idea that humanity should passively follow nature’s brutal laws of survival, instead arguing that true ethical progress comes not from imitating the cosmic process, nor from escaping it, but from actively combating it. Nature’s method—what he called the gladiatorial theory of existence—favours the strong and ruthlessly eliminates the weak. In contrast, ethical societies do the opposite: they protect the vulnerable, foster cooperation, and prioritize mutual aid over selfish domination. This rejection of raw Darwinism in ethics highlights the essential human struggle—not to surrender to nature’s harsh rules but to overcome them through conscious effort.

Ethics, like intelligence, has evolved over time. Just as human reasoning has advanced beyond instinct, so too has morality developed from primitive tribal rules to complex social systems. This suggests that ethical evolution is not merely a passive reaction to external pressures but an active force that helps shape the world. Ethical progress depends on our ability to recognise that freedom is more than just acting on impulse—it is the capacity to make deliberate moral choices based on reason and reflection. Without this, ethics would simply be another predetermined mechanism of survival, rather than a guiding principle for conscious evolution.

And so, by challenging the deterministic view that ethics is merely an extension of natural selection, this argument reaffirms the role of human agency. Science may provide the tools to understand the world, but only ethics can decide how those tools should be used. If ethics is to have meaning, it must remain firmly rooted in human choice, responsibility, and the ongoing struggle to shape a more just and cooperative society.

Progress is often measured by technological advancements and accumulated knowledge, yet true civilization is not just about external achievements—it also depends on the development of human nature itself. While science has developed with remarkable speed, human ethics, moral character, and social responsibility have lagged behind. Many capacities within individuals remain underdeveloped simply because the right conditions to bring them forth have not yet been provided. If human improvement is to keep pace with scientific progress, then education—particularly ethical education—must be at the center of societal advancement.

Among all the forces shaping civilization, ethical education stands out as the most promising path to social progress. It is more than just teaching moral values; it is about fostering a shared sense of responsibility, cooperation, and purpose across different classes, races, and nations. Without a common foundation in ethics, knowledge alone cannot ensure a better society. Though science may provide tools for improvement, without ethical direction those tools could be misused or fail to create meaningful change.

True human progress is not simply about discovering new scientific principles or refining technological capabilities—it is about improving the intellectual, physical, and moral character of individuals. Any effort to better society must focus on enhancing the capabilities people already possess, rather than relying on speculative advancements in genetics, social engineering, or other experimental solutions. Science has already given humanity the knowledge needed to build a rational, ethical world—what remains is the task of applying it.

Science, at its core, is an engine for discovering truth—but ethical progress requires more than truth alone. Societies must learn how to apply knowledge for the benefit of all mankind, and this requires a system of shared ethical principles rooted in rational thought. The ultimate goal is not just scientific advancement, but a world where moral reasoning and courageous decision-making guide human affairs.

Yet, as powerful as science is, it cannot stand alone in shaping the future. Science and religion must work together—not as opposing forces, but as complementary ones. And Conklin then continues, outlining ethics as an influencer of every field of human existence, and even work at a much faster pace than eugenics itself.

Ergo, what Conklin here describes is from science, ethics are derived in the form of a teleological universal moral framework, where scientific insights inform ethical directives aimed at shaping human behavior and governance. However, for this to result in a truly universal moral framework, the perspective applied must be a subjective, collective interpretation of the scientific data, as raw empirical facts do not inherently prescribe moral imperatives. What emerges, then, is a universal moral framework synthesized from data but perceived through a collectivist, subjective experience, where institutions, cultural paradigms, and ideological structures dictate its application. This is evident in Edwin Grant Conklin’s Science and Ethics, where he describes how ethics has evolved alongside human intelligence and social structures, progressing from primitive survival instincts to more complex moral ideals such as justice and cooperation. His assertion that ethics has expanded from tribal to national and international levels mirrors the process of collective interpretation shaping ethical standards on a global scale.

And this all aligns closely with Bogdanov’s empiriomonism, which asserts that knowledge—including scientific knowledge—is not purely objective but is constructed through collective, functional interpretation. Bogdanov maintained that truth is not an absolute reflection of reality but a product of coordinated human activity, meaning that ethics, like science, is shaped by social organisation rather than discovered independently.

And this in turn reinforces the hierarchical structuring of ethics as an adaptive, teleological mechanism, where those who control the collective interpretation of scientific data ultimately define the ethical trajectory of governance and society… taking us ultimately to the Omega Point.

Over the past months, we have examined how ethics has been systematically developed as a mechanism of control across multiple domains—business, religion, and global governance. No longer just a philosophical or moral guide, ethics has been weaponised, shaping legislation, governance structures, and cultural norms.

But these ethics are ultimately the result of interpreted scientific data, filtered through a collective yet subjective perspective—aligning with Bogdanov’s Empiriomonism, where knowledge and reality are shaped by social experience and ideological framing rather than objective absolutes.

And Hermann Cohen’s Infinite Judgment, as promoted through the Institute of Noahide Code, presents a framework in which ethics is not merely advisory but eventually codified into law. This aligns with not only authoritarian states of the past, but furher the objectives of UNESCO and WAAS, which work to embed these ethical principles into cultural narratives, effectively transforming them into a mechanism for moral encoding at the societal level.

Cohen himself openly suggested using religion as a tool to achieve this goal, reinforcing the idea that ethics can be engineered and imposed rather than organically developed. And all of this aligns entirely with Bogdanov’s Proletkult, where culture becomes a vehicle for ideological transformation, shaping collective consciousness to serve a predetermined social order.

And Bogdanov’s Proletkult, in turn, functions as a mechanism to steer humanity as a collective—the human super-organism—structured through Bogdanov’s Tektology, which applies systems theory to social organization, treating society as a self-organizing, adaptive structure directed toward a unified evolutionary trajectory.

But beyond theoretical structures, we have further observed how ethics is actively being used to justify censorship, framing restrictions on speech and information as moral imperatives. Ethics is not only positioned as the foundation of ‘good governance’ but also as a justification for expanding state control under the guise of security and public interest. Even 9/11, a pivotal event in modern geopolitics, was framed through the lens of security ethics, where ethical justifications have been invoked to reshape surveillance, policy, and governance on a global scale.

And this expansion of macro-ethics logically leads to a hierarchical ethics system, as envisaged by Ken Wilber and others—alternatively framed as Moral Foundations Theory by Jonathan Haidt—where ‘cosmic ethics’ ultimately reigns supreme, with ‘planetary ethics’ and ‘humanitarian ethics’ typically occupying the next levels in the hierarchy.

And this all reveals a clear pattern—ethics is no longer simply about defining right and wrong in an abstract sense. It has become a system of control and compliance. When engineered from the top down, ethics ceases to be a guiding principle for individual or societal moral reasoning and instead becomes a directive instrument, designed to shape behavior, justify authority, and reinforce power structures.

And ethics also serves as a crucial component in Alexander Bogdanov’s conceptualizations. First, as an output of Empiriomonism, where knowledge is shaped by collective perception, which then feeds into Proletkult, ultimately guiding the human super-organism, as defined through Tektology.

What this ultimately reveals is that Alexander Bogdanov, in short, created a hyper-manipulative tool of global control—a self-sustaining system where ethics is engineered to shape collective consciousness, steering humanity in a predetermined direction. And at this stage, the critical component in this pipeline should be patently clear. And it is this very system that is now being actively implemented through organizations like the Collegium International, IUCN, WAAS, and UNESCO.

And while the 1941 conference, titled Science and World Order, chiefly outlined the aims, Science and Ethics (1942) detailed the means—the ethical framework through which those objectives could be justified, implemented, and enforced.

And with that said, it’s time to draw a line under ethics. If these many articles do not prove my case, I fail to see how anything ever could.

Science provides the tools, knowledge, and means to achieve outcomes—but it does not answer the fundamental question: ‘why?’ It can explain processes, predict outcomes, and offer solutions, yet it remains silent on what should ultimately be pursued. However, when science is transformed into an ethical imperative, it gains direction, defining not just what can be done, but what must be done.

By projecting this science-derived ethic into the future, it becomes more than just a framework for understanding—it evolves into a directive force, actively shaping the course of human development and evolution. Through Conscious Evolution, guided by reason and scientific principles, humanity can take control of its own progress, steering its future with intention rather than leaving it to chance—exactly as T.H. Huxley proposed in 1893.

And that even logically explains the roles of Teilhard, Barbara Marx Hubbard, and others in the equation—by framing Conscious Evolution as the next stage of human development, where science, ethics, and spirituality merge into a directed evolutionary process, ultimately leading to the Omega Point. Their work envisions a future where ethics is no longer a passive moral guide but an active force steering human progress, aligning with the broader agenda of shaping world affairs via…