D(eception)-Day

We’ve discussed this treaty before — but that’s no reason to let it go. If anything, the issue is so pivotal it demands constant repetition — if only to compensate for the total media blackout that has surrounded it for decades.

Because in hindsight, it becomes increasingly clear that a single dotted-line didn’t just alter policy — it catastrophically undermined the West. And that dotted line was signed by Richard Nixon in Moscow, on the 23rd of May, 1972.

This wasn’t a simple case of infiltration or internal collapse — though elements of both exist. The reality was of far more insidious character. By gradually shifting the global narrative away from East–West antagonism and toward the spectre of environmental catastrophe, the distinction between socialism and capitalism could, over time, be rendered irrelevant. In its place emerged a technocratic regime — one that used global surveillance, modelling, and apocalyptic predictions to herd both populations and global politicians in the same direction. The result: a global policy-setting apparatus operating above national parliaments and civil services, all under the banner of the so-called ‘common good’ and the well-being of the global citizen. And the disaster forecasts came in thick and fast, courtesy of the ICSU, IIASA, and IPCC — your favourite unelected technocrats, operating entirely beyond both reproach and democratic accountability.

And this, incidentally, was Egle Rindzevičiūtė’s core argument in her The Power of Systems1 — that Cold War ideological rivalry was gradually displaced by a shared reliance on systems analysis and cybernetic planning, particularly through institutions like IIASA. In this new paradigm, politics gave way to technocratic problem-solving, and the distinction between socialism and capitalism was quietly neutralised — replaced by a common administrative language through which governance could be harmonised without ideological confrontation.

But what’s more remarkable is that precisely this strategy was later affirmed — almost verbatim — by Mikhail Gorbachev in a speech delivered in 1987.

But that’s not the end of it. In 1975, the Belgrade Charter2 was introduced — a declaration calling for the integration of environmental education into school curricula worldwide. Its 1976 follow-up at the North American Regional Seminar went even further, advocating the use of mass media to promote ‘alternate lifestyles’ as part of a broader cultural shift3.

The only problem? There was no coherent science underpinning any of it. Global temperature trends showed no consistent pattern, and even the key institutions involved — along with leading figures like Bert Bolin — openly admitted they didn’t yet understand the climate system nor the carbon cycle. In other words, they were constructing the machinery for mass indoctrination before they’d even settled on the message. Which means, in plain terms, there was precisely a 0% chance this was ever grounded in legitimate science.

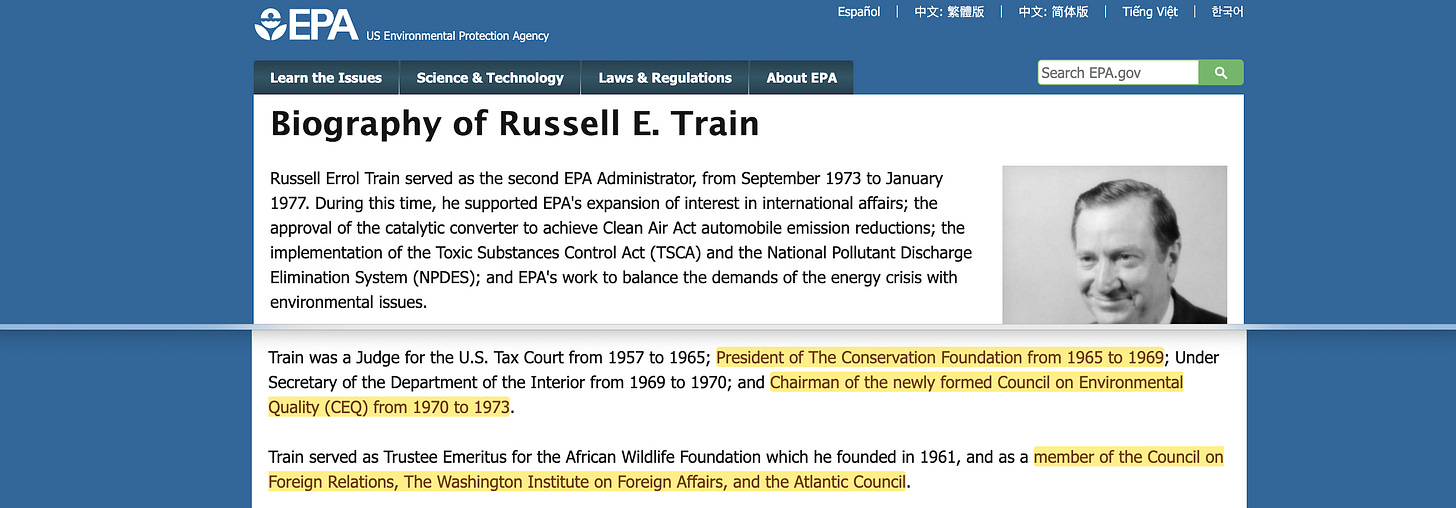

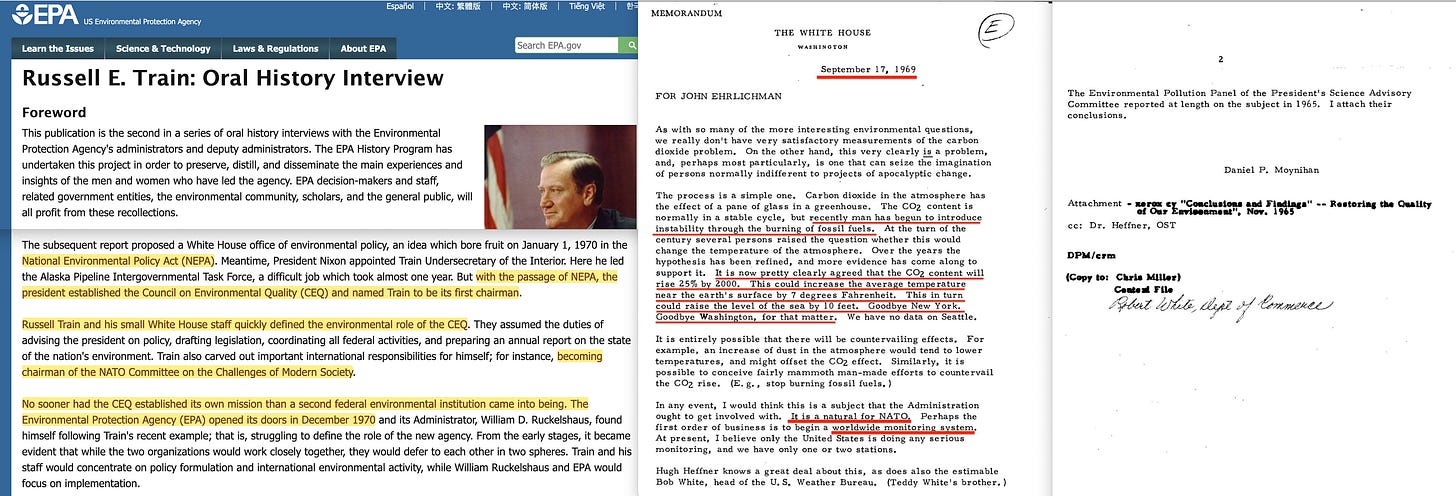

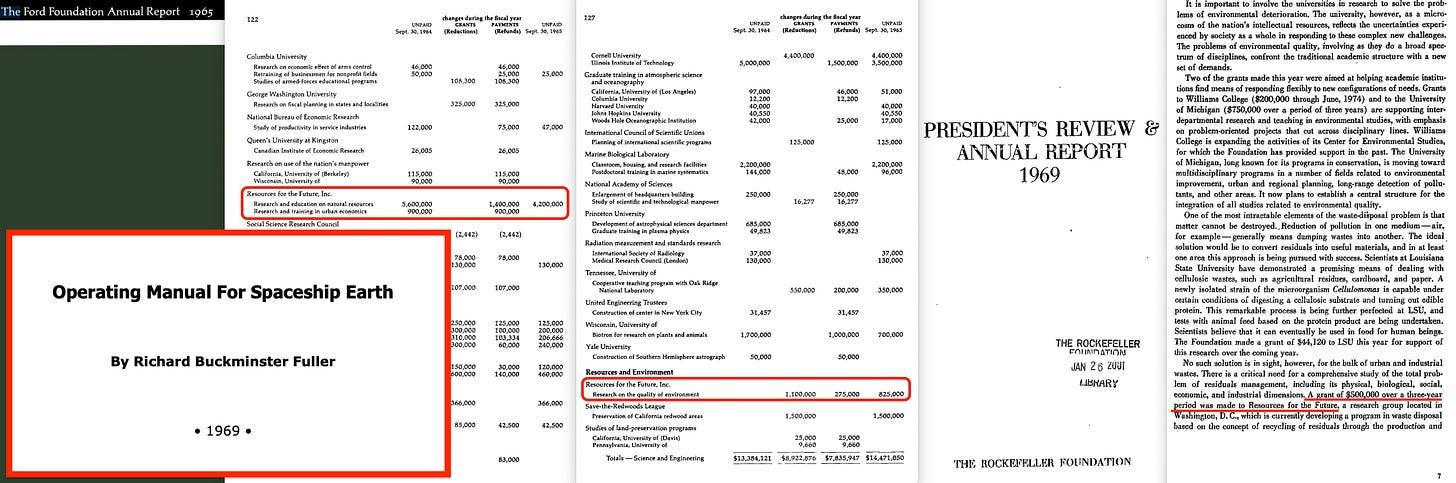

At the time of the treaty, the Environmental Protection Agency4 (EPA) had existed for just eighteen months, and the Council on Environmental Quality5 (CEQ) had been established only a year prior — both direct outgrowths of the National Environmental Policy Act6 (NEPA), launched almost immediately after Nixon took office. These institutions were stacked with Rockefeller Foundation alumni and veterans of the Conservation Foundation — itself almost entirely funded by Rockefeller. And with Henry Kissinger7, Russell E. Train8, and Lynton K. Caldwell9 in central roles10, the CEQ and EPA took a step that — viewed objectively — appears almost indistinguishable from treason.

At the height of the Cold War — with the Soviet Union still publicly committed to defeating liberal capitalism — the United States agreed to bind itself structurally to its ideological adversary. Not through arms, but through environmental cooperation — a domain where critical data would be filtered through opaque processes and technocratic institutions built precisely for this purpose. And not merely for investigative purposes, but for legal and administrative alignment — the joint development of policy between the two superpowers.

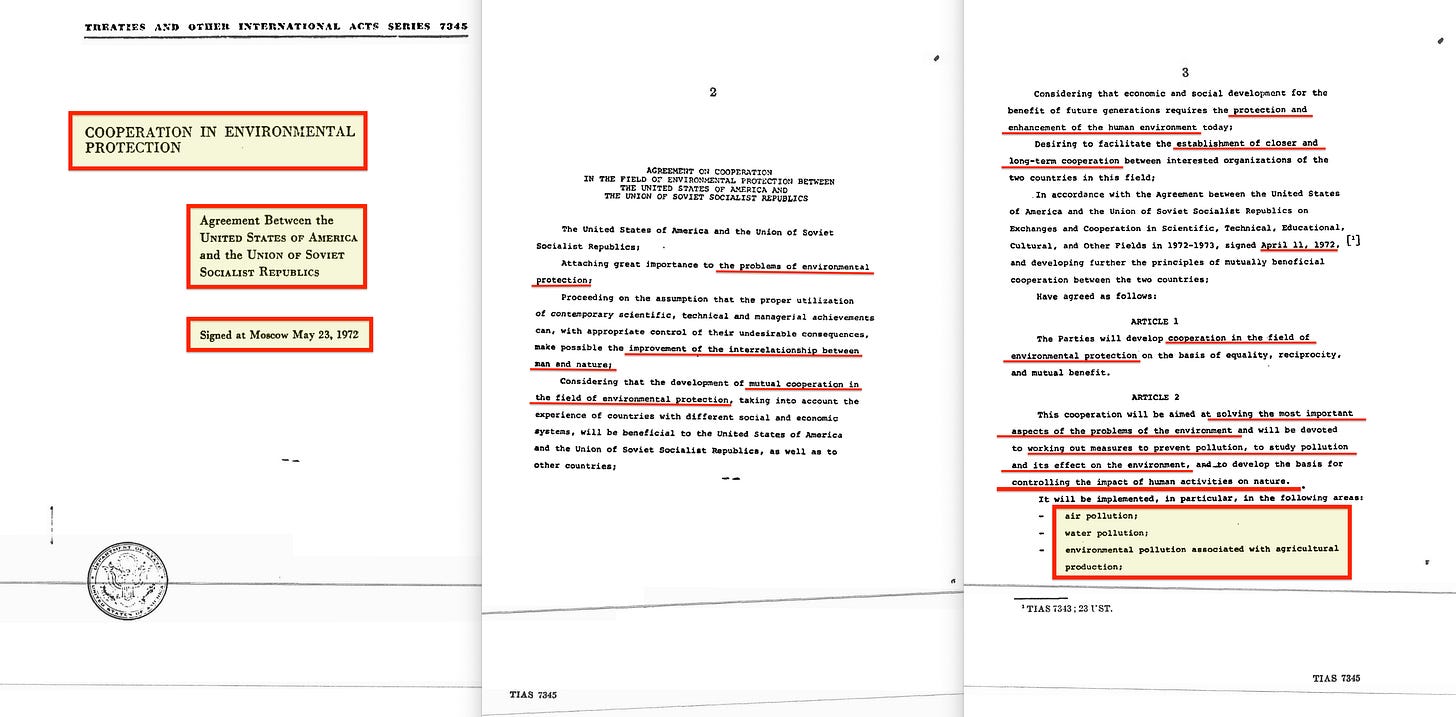

The Agreement Between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on Cooperation in Environmental Protection11, signed in Moscow on 23 May 1972, laid the foundation for East–West convergence — not through diplomacy, but through bureaucratic alignment. It established a Joint Committee to coordinate, approve, and assign duties across agencies in both nations — an unelected, binational body operating above sovereign constitutional structures. Leading the American delegation was none other but Russell E. Train, a man closely affiliated with the Rockefeller-funded Conservation Foundation.

This was the key document in the prior post, Discovery.

In very brief:

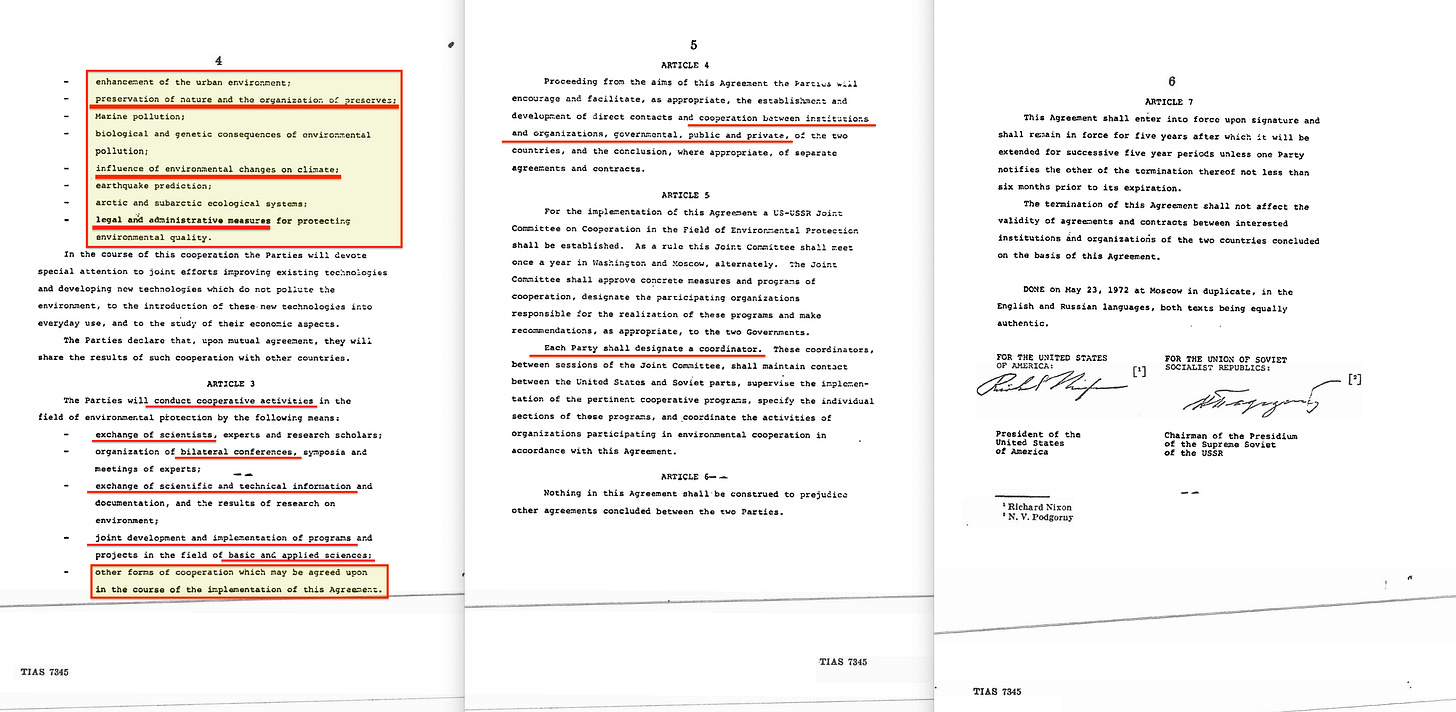

What Moscow agreed to - per 1972 treaty - was to perform ‘joint development and implementation in the fields of basic and applied sciences‘ for sakes of ‘controlling the impact of human activities on nature‘ through the development of ‘legal and administrative measures for protecting environmental quality‘.

In short: the adoption of shared environmental policy. And never mind the ideological divide.

But Train was also in a conflicted position12. At the same time he was leading negotiations on behalf of the U.S. with the Soviet Union, he also held a senior role within NATO’s Committee on the Challenges of Modern Society13 (CCMS). And the CCMS, by no coincidence, had a very specific mandate during this exact period: to design and implement a mechanism for global environmental monitoring. This objective was spelled out explicitly in the Moynihan Memo of September 17, 196914 — a classified directive that called on NATO to spearhead the development of worldwide ecological surveillance infrastructure.

In other words, while Train was tasked with engineering East–West convergence through U.S.–Soviet cooperation, he was simultaneously embedded in a Western defence bloc planning the global environmental apparatus that would serve as the foundation for that very convergence.

And this should have been known to Moscow. In fact, there is zero possibility it wasn’t — because of Viktor Kovda. Kovda wasn’t merely a Soviet soil scientist; he was the USSR’s key liaison for international scientific coordination. He played a central role in securing ICSU’s early involvement with UNESCO, helped launch the foundational structure of SCOPE, and by 1973 had become its president. And it was SCOPE — the very institution Maurice Strong commissioned in 1971 — that produced the blueprint for global environmental monitoring which would evolve into GEMS. In other words: the Soviets were fully aware that environmental cooperation meant policy harmonisation, legal convergence, and the gradual restructuring of governance — all while NATO built global satellite surveillance infrastructure under the guise of environmental stewardship, per the Moynihan Memo. And they also knew that the man overseeing that NATO project was the very same man negotiating the May 23, 1972 treaty — Russell E. Train.

And yet, they still moved forward with it.

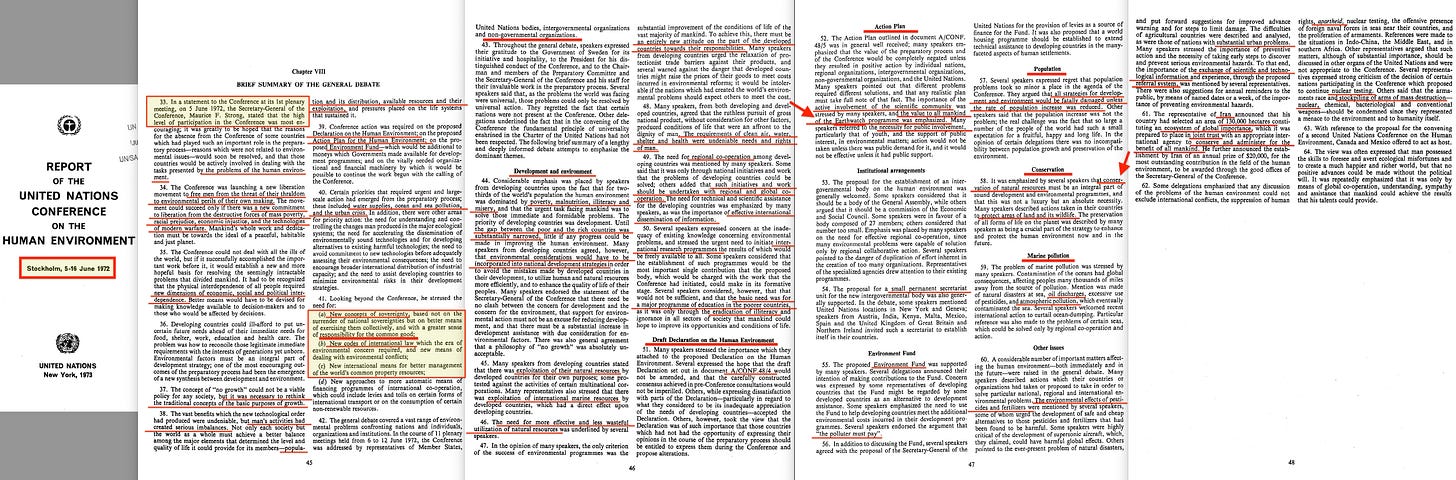

Weeks after that fateful action by Nixon, the 1972 Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment15 formalised the global agenda. Maurice Strong16 — Secretary-General of the Conference17 and Rockefeller’s environmental18 point man19 — was the one who shepherded the process into the open. From this event emerged UNEP: the United Nations Environment Programme20, tasked with coordinating and enforcing environmental governance on a global scale.

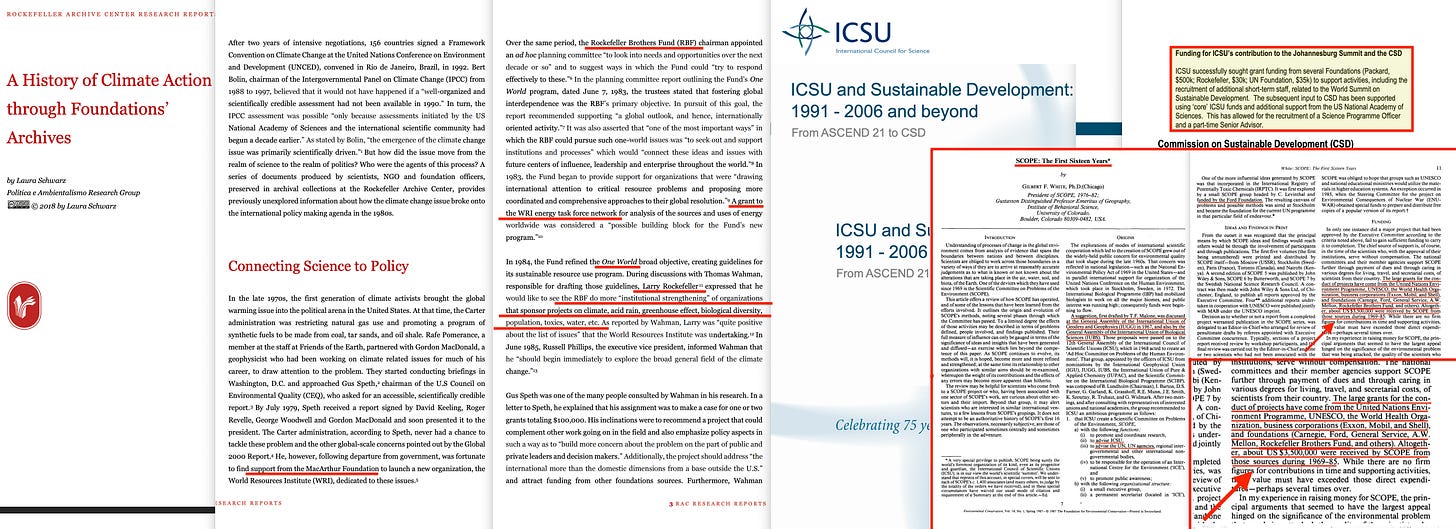

But well before Stockholm convened, Strong had already laid the groundwork. In the lead-up, he commissioned a report from the Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE), established in 1969 by the International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU). This same committee — with Viktor Kovda involved from the outset — would go on to coordinate many of the technocratic institutions that followed, including early research into the global carbon cycle and the foundational frameworks for anthropogenic climate change theory.

The first SCOPE report, commissioned by Maurice Strong in 1971, was soon followed by an action plan to implement the Global Environment Monitoring System (GEMS) — a global surveillance infrastructure designed to capture and process environmental data across borders under the guise of planetary stewardship. That same year, the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) was founded as a joint U.S.–Soviet modelling hub, tasked with integrating that data into long-term socio-economic planning. Over time, IIASA became the central node for processing the surveillance streams generated by GEMS.

Consequently, environmental science primarily came through research carried out by foundation21 funded22 ICSU and SCOPE23, surveillance through GEMS, and modelling through IIASA — with each feeding into a unified output stream that enabled prediction, planning, and joint policymaking between the world’s superpowers. The technocratic pipeline was in place long before anyone realised what was happening — aided, of course, by a mainstream media that utterly failed in its most basic duty.

But since we last walked through this timeline, further documents have emerged — and they clinch the point beyond all reasonable doubt. The consequences of the May 23, 1972 agreement are not speculative; they are plainly visible in the international bureaucracies, environmental treaties, surveillance mechanisms, and legal norms that govern society today. These developments were rolled out gradually, almost imperceptibly, while the public remained distracted by whatever topics the mainstream media deemed important. The treaty itself quietly spawned an entire web of follow-up agreements — none of which were subjected to democratic debate, publicly identified as derivatives, or treated with anything close to the gravity they deserved.

Because this cooperation in environmental protection was not merely the planned beginning of a new world order — it was the planned end of Western liberalism itself. And yet, through thick Aesopian framing, it was presented as its very safeguard by a media establishment that had absolutely no interest in covering it appropriately.

Richard Nixon was widely considered a staunch Republican. Yet many of the foundational environmental policy measures came into being under his leadership. It began with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), signed into law on January 1, 1970. This legislation led to the creation of the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), which quickly became central to early policy development and administrative oversight. It also served as an advisory body to Nixon — who, later that same year, established the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

The EPA was granted the authority not only to implement and enforce policy but, in some cases, to draft it outright — all without direct congressional oversight. In effect, the agency was empowered to legislate within its own domain.

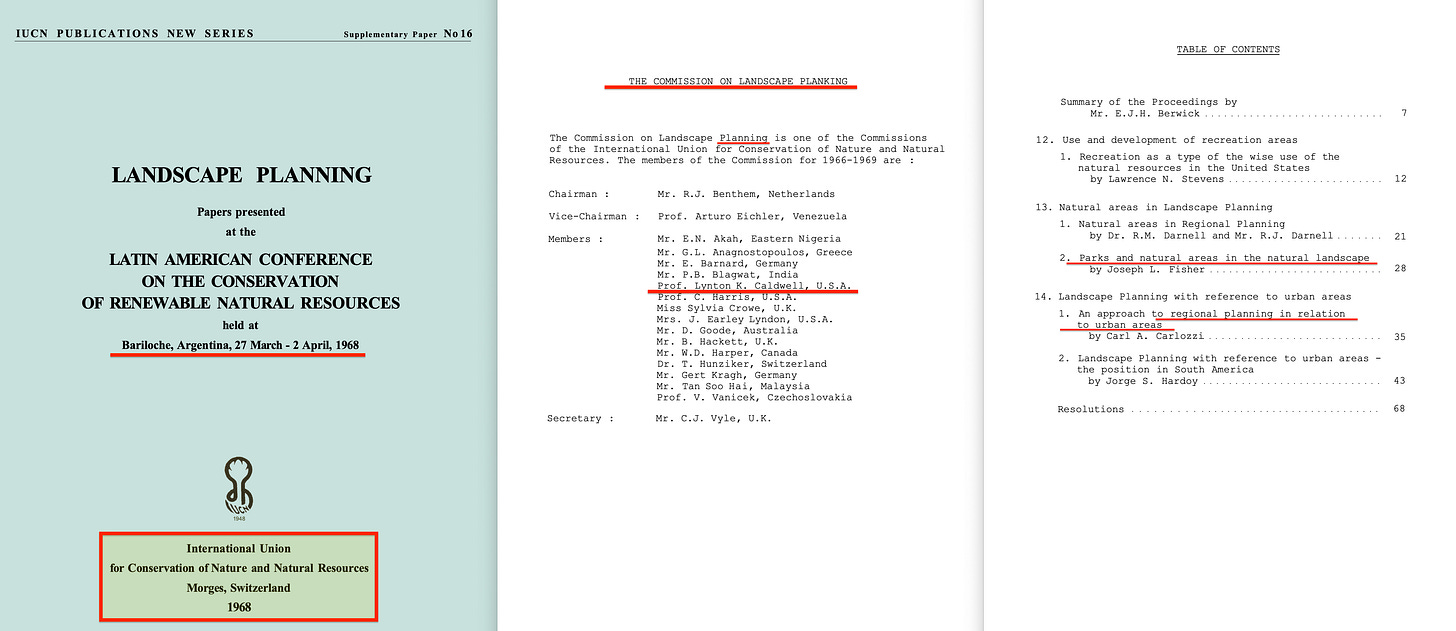

A key figure in all of this was Lynton K. Caldwell, the principal architect behind NEPA24. What is less widely acknowledged, however, is that Caldwell was simultaneously serving on the IUCN's Landscape Planning Committee25. In other words — the very man who drafted the pivotal environmental legislation for the United States was, at the same time, collaborating with a global NGO to shape the blueprint for future Integrated Landscape Management.

Put plainly: a senior figure within an international NGO — one which today calls for 50% of the world’s land and sea to be set aside as ecological reserves2627 — also penned the American legislation that would ultimately become the mechanism for just such a land grab.

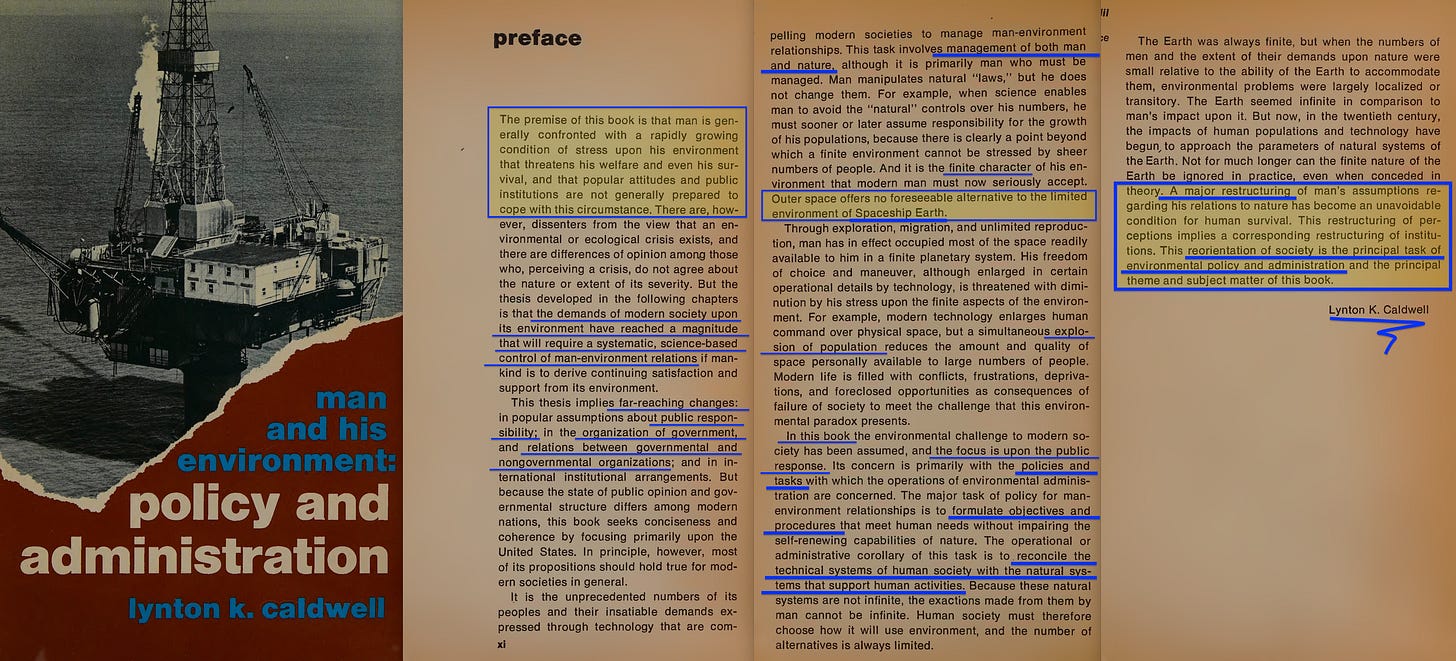

And in 1975, Lynton published a book titled Man and His Environment28, which set the tone early in the preface:

The premise of this book is that man is generally confronted with a rapidly growing condition of stress upon his environment that threatens his welfare and even his survival, and that popular attitudes and public institutions are not generally prepared to cope with this circumstance

But — conveniently — Caldwell already had the solution lined up:

… the demands of modern society upon its environment have reached a magnitude that will require a systematic, science-based control of man-environment relations if mankind is to derive continuing satisfaction and support from its environment.

And what, exactly, is required to achieve the systematic management of man’s environment? Of this, he’s quite clear:

This thesis implies far-reaching changes: in popular assumptions about public responsibility; in the organization of government, and relations between governmental and nongovernmental organizations; and in international institutional arrangements.

In plain terms: a total restructuring of society. Not just perceptions, but institutions. Not just national, but international.

It is the unprecedented numbers of its peoples and their insatiable demands expressed through technology that are compelling modern societies to manage man-environment relationships. This task involves management of both man and nature, although it is primarily man who must be managed.

However... that doesn't appear to gel with capitalism or the individualistic ethos of the West. Yet, as Caldwell puts it, there is quite simply no alternative:

Outer space offers no foreseeable alternative to the limited environment of Spaceship Earth

Excellent. We have now firmly established that this all ties back to the Spaceship Earth narrative — which, in short, portrays the planet as a closed-system General Systems Theory model.

The major task of policy for man-environment relationships is to formulate objectives and procedures that meet human needs without impairing the self-renewing capabilities of nature. The operational or administrative corollary of this task is to reconcile the technical systems of human society with the natural systems that support human activities.

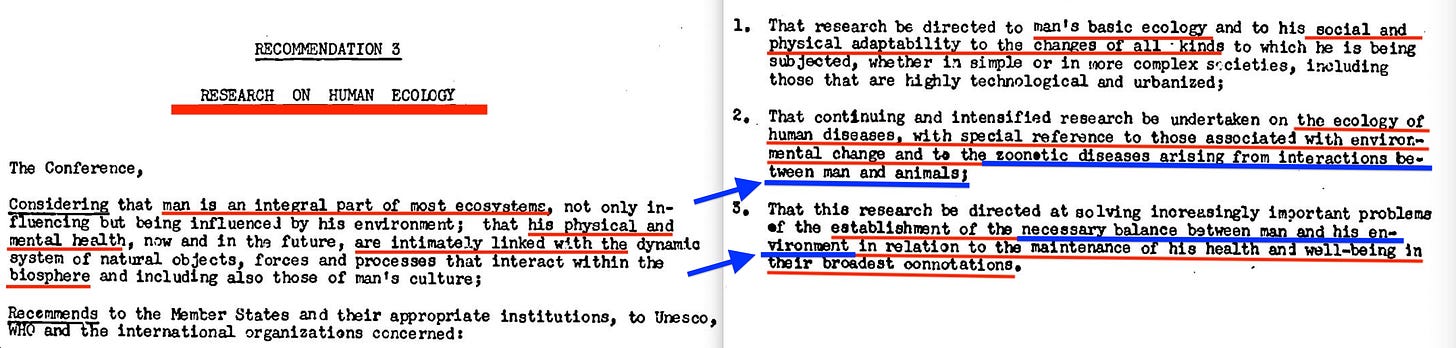

And he further adds that the real task is the creation of objectives and procedures — in other words, policy — that will balance humanity with nature. The same concept outlined through recommendation 3 in the 1968 UNESCO Biosphere Conference.

Also make sure to check out 3.2 which explicitly drags in zoonotic disease.

Not for much longer can the finite nature of the Earth be ignored in practice, even when conceded in theory. A major restructuring of man’s assumptions regarding his relations to nature has become an unavoidable condition for human survival. This restructuring of perceptions implies a corresponding restructuring of institutions. This reorientation of society is the principal task of environmental policy and administration and the principal theme and subject matter of this book.

… and we’re not even out of the preface!

The entire book is effectively an ode to planetary management — an idea first laid out in the January 1969 issue of the UNESCO Courier, which presented a clear blueprint for global environmental governance29. Rather than dissect every section of Man and His Environment, we’ll focus on the most telling passages. Because while the book presents itself as a sober call for planetary stewardship, it is in fact a foundational text for systemic population control, behavioural conditioning, and resource regulation — all dressed in the language of science.

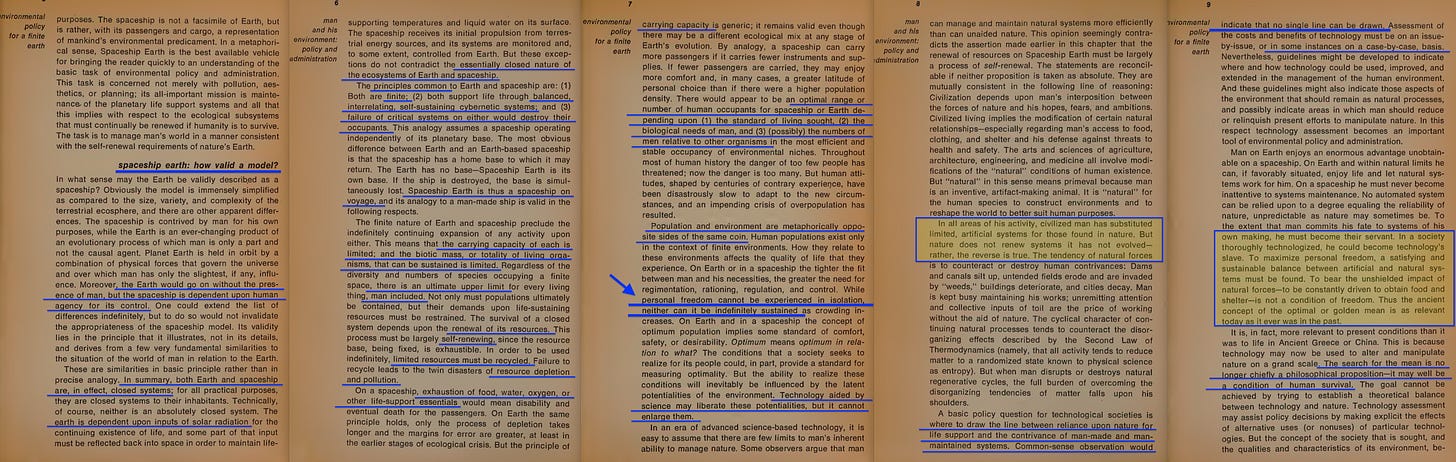

Early on, the text considers the legitimacy of the ‘Spaceship Earth’ metaphor, concluding that both Earth and a spaceship must be understood as closed systems — self-contained, with finite resources, and reliant on internal recycling to survive the journey. The Earth could easily continue without humans — but the spaceship cannot. Therefore, human agency becomes essential to maintaining ecological balance. From here, the logic of the circular economy is born: a system where material inputs must be endlessly recycled to prevent collapse, and where resource use must be tightly rationed to avoid exceeding the planet’s carrying capacity.

Crucially, managing this closed-loop economy requires Input–Output Analysis — a systems modelling tool that maps the flow of materials and energy through economic processes. But to function globally, such analysis demands something else: comprehensive, planetary-scale surveillance.

But Caldwell doesn’t stop at resource management — he explicitly argues that human freedom cannot be sustained indefinitely within a closed system. It further frames man and environment as opposite sides of a coin: liberty, if unchecked, leads to ecological disaster. And while technology may appear to enhance life-support systems, the authors caution that the opportunities it creates remain constant — a direct swipe at the myth of infinite innovation. In short, mankind doesn’t improve nature — it simply stresses it further, and that is inherently unsustainable.

This leads to the book’s central dilemma: where does one draw the line between man-made solutions and natural limits? The proposed answer is revealing — decisions must be made on a ‘case-by-case’ basis by experts, who will assess when and where technology may be allowed. In other words, technocratic mediation becomes the solution. An unelected class of institutional gatekeepers — Plato’s modern-day Philosopher-Kings30 — is called upon to decide what constitutes legitimate use. It’s a convenient mechanism for those who seek to govern through permanent exception.

Ultimately, it all converges on the question of the Aristotelian Golden Mean — a sustainable midpoint between personal liberty and planetary boundaries. But in this context, the ‘mean’ is no longer a matter of philosophical reflection or moral virtue. It is reframed as a condition of survival. And in the hands of systems theorists and global planners, it becomes a pretext for regulating every aspect of human existence — from energy consumption to reproductive behaviour — all justified in the name of maintaining ecological balance. This is no longer ethics in the classical sense. It is the moral architecture of a closed system — rationalised, administered, and ready to be enforced. And this, quite simply, is a requirement — or so we’re told — lest we all burn in a lake of fire.

Again.

In the context of the Spaceship Earth metaphor, Buckminster Fuller’s famous call for an ‘Operating Manual’ is cited31 — though Caldwell immediately cautions that writing such a manual doesn’t imply we’ll be capable of using it, highlighting the gap between conceptual awareness and practical implementation. A 1969 attitude survey by Resources for the Future — itself flush with foundation32 funding33 — revealed a general lack of concern among leaders regarding environmental responsibility, reinforcing the point that the concept was nowhere near ready for deployment.

While individuals may acquire the label of ‘good citizen’ by aligning with objectives, real transformation demands something far deeper. As Kenneth Boulding warned, shifting from an open-system economy to a closed-system Spaceship Earth model requires a wholesale change in worldview — comprising not just economics, but also logic, education, ethics, and, crucially, politics. Caldwell conclude that without such sweeping changes, the environmental agenda will rarely ‘get to the root of the problem’, and instead remain locked in superficial fixes.

What is urgently called for, Caldwell argues, is:

… the development of a credible, operational ideology, or coherent set of principles, is a prerequisite for a polity of finite Earth and for a truly effective management of modern man's environmental problems.

This, in turn, demands that science not only be called upon to provide insight — but be elevated as the basis for a new kind of politics. A probabilistic ‘science-based politics’ that is problem-oriented rather than interest-driven, and explicitly redefines the relationship between private and public interests. Man, in this schema, must adapt to the finite parameters of Spaceship Earth — as determined by science and technology — with politics repurposed as the guiding mechanism of compliance.

Several organisations are already well-positioned for this transition. The AAAS, which helped launch the Society for the Advancement of General Systems Theory in the 1950s; the ICSU, with its global scientific networks; and the IUCN — founded by Julian Huxley — which, in 1956, notably changed its name to the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources34. This shift not only echoed the language of planetary stewardship embedded in the Spaceship Earth metaphor, but also broadly aligned with Caldwell’s ideological framework.

Ultimately, this approach calls for the fusion of science, ethics, and political behaviour — and in yet another of history’s extraordinary coincidences, this same ambition was pursued in 1969 by the Groupes des Dix35, a cybernetics- and systems-theory collective associated with Edgar Morin. Though the group eventually faded from view, its core objective — the synthesis of science and politics — was later resurrected through the Collegium International in 2002, whose mission mirrors that same formula, now channelled explicitly through a world ethic36.

We’ll skip the remainder of Man and His Environment: Policy and Administration by Lynton K. Caldwell, as it essentially elaborates and operationalises the exact worldview already outlined above:

Spaceship Earth as a governing metaphor

The need for a new science-based politics

The fusion of science, ethics, and political behaviour

A shift from interest-based to problem-oriented policy

And a call for systems-level transformation of institutions, economics, and law to align with environmental limits.

Each subsequent chapter expands on how these ideas should function administratively — including legal reform (via NEPA), institutional inadequacies, the role of international agencies (UN, ICSU, IUCN), and the importance of a scientifically literate bureaucracy.

Caldwell also contributed elsewhere — for example, an essay titled The Coming Polity of Spaceship Earth, largely reiterating the same theme. He draws in Adlai Stevenson’s 1965 United Nations speech37, likely the first intentional invocation of the Spaceship Earth metaphor in a contemporary context. The chapter expands on the political dimension, arguing that the science-based politics of the future must be grounded in environmental science. It reaffirms the central role of the ICSU, and asserts that humanity must reform its behaviour to counteract its own destructive tendencies — the same message repeated since the 1968 UNESCO Biosphere Conference. Finally, Caldwell calls for the ‘collective efforts of many intelligent participants and followers’ — which, on the surface, reads too close to collectivism for comfort.

In essay 26, the message take a significantly darker turn, with man described explicitly as a planetary disease — a species so destructive that it now threatens its own extinction. But the core struggle is not one of capitalism versus communism, but of planetary survival. The true battle is not ideological in the traditional sense; it is between those who embody environmental stewardship and those deemed pathogens — individuals or institutions standing in the way of biospheric order.

In essence, the text frames those acting in personal or decentralised capacity as the core threat — for only in a centrally controlled, top-down society could a so-called planetary doctor act to ‘treat’ the crisis. And who exactly are the pathogens? The military, corporations, industrialists, and those acting in individual capacity — all are implicated. McHarg even goes so far as to label those not in alignment with the prevailing ecological ideology as ‘loathsome’, ‘beyond salvation’, and ‘filthy’ — language disturbingly resonant with Nazi-era dehumanisation tactics.

As for the author in question, Ian McHarg38, he ‘… was one of the most influential persons in the environmental movement who brought environmental concerns into broad public awareness and ecological planning methods into the mainstream of landscape architecture, city planning and public policy‘.

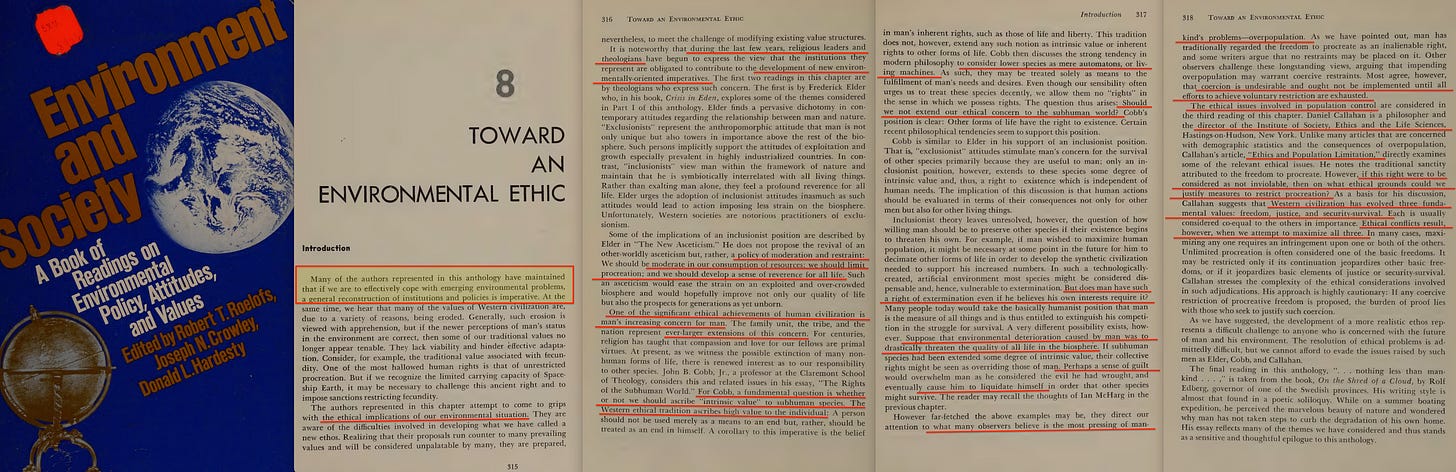

The following Chapter 8, Toward an Environmental Ethic, prefigures the very framework later institutionalised through the Earth Charter in 2000 — a document heavily influenced by Maurice Strong and Rockefeller-aligned networks.

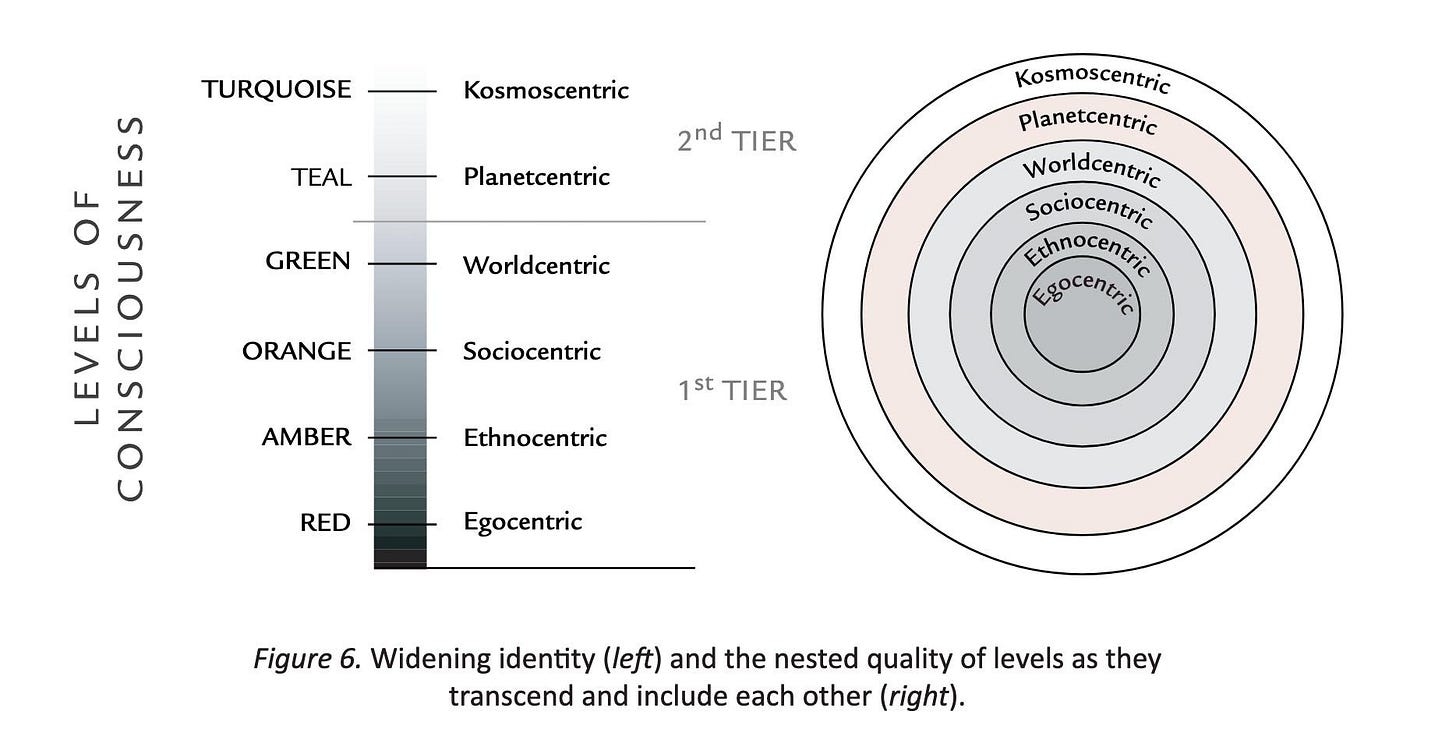

The chapter emphasises the need to live ethically within the planet’s carrying capacity, but it goes further — proposing a moral expansion that begins with concern for one’s family, tribe, and nation, and extends outward. It frames this as one of the ‘significant ethical achievements’ of civilisation — a concept in full alignment with Ken Wilber’s notion of expanding identity from the egocentric to the ethnocentric and eventually to the worldcentric, and beyond39.

But it then raises a deeply unsettling question:

Should we not extend our ethical concern to the subhuman world?

This is the core of the argument — the suggestion that the biosphere itself, and the collective rights of non-human species, could morally override those of human beings. The authors speculate that environmental destruction may one day prompt humanity to ‘liquidate itself’ out of guilt, so that other species may survive.

Further, it openly discusses population control, calling unrestricted procreation ‘one of the basic freedoms’, but one that may need to be restricted if it conflicts with justice or ‘security-survival’. And while it admits that coercion should be a last resort, the mere fact that coercion is floated at all reveals the underlying logic of top-down control.

Ultimately, this ideology is antithetical to classical Western values — which prioritise individual human liberty — and replaces them with a framework where humans are a managerial class within a planetary system, accountable not to God or reason, but to biospheric constraints.

The agenda running through the 1974 anthology Environment and Society: A Book of Readings is nothing short of revolutionary. Ian L. McHarg’s contribution, Man: Planetary Disease, lays it bare — humanity is framed not as a flawed steward, but as a disease. The solution is not eradication but top-down management. That theme runs throughout the volume, most clearly in Lynton K. Caldwell’s call for the wholesale restructuring of public institutions, cultural values, and governance systems to bring them into alignment with the emerging paradigm of environmental administration rooted in systems theory.

The Spaceship Earth metaphor dominates, portraying the planet as a closed system requiring oversight, regulation, and behavioural steering. In Part 8, Toward an Environmental Ethic, the moral framework is formalised: individual liberty must yield to planetary necessity. This isn’t theoretical musing — the contributors include key actors from the United Nations, global NGOs, and national regulatory bodies. They weren’t merely theorising — they were operationalising.

What emerges is scientific socialism cloaked in ecological concern. Central planning, behavioural conditioning, and administrative convergence are framed not as ideological choices but as unavoidable necessities. Democracy is peripheral at best. The synthesis of ethics, ecology, and administration reflects the total systems vision of Alexander Bogdanov: consensus science as epistemic control (empiriomonism), population reconditioning (proletkult), and institutional integration through Tektology — his precursor to general systems theory. The resurrection of this framework — mapped to carbon accounting, planetary modelling, and ‘managed sustainability’ — completes a loop that began with UNESCO in 1968 and ends in the quiet normalisation of a closed-world technocratic regime.

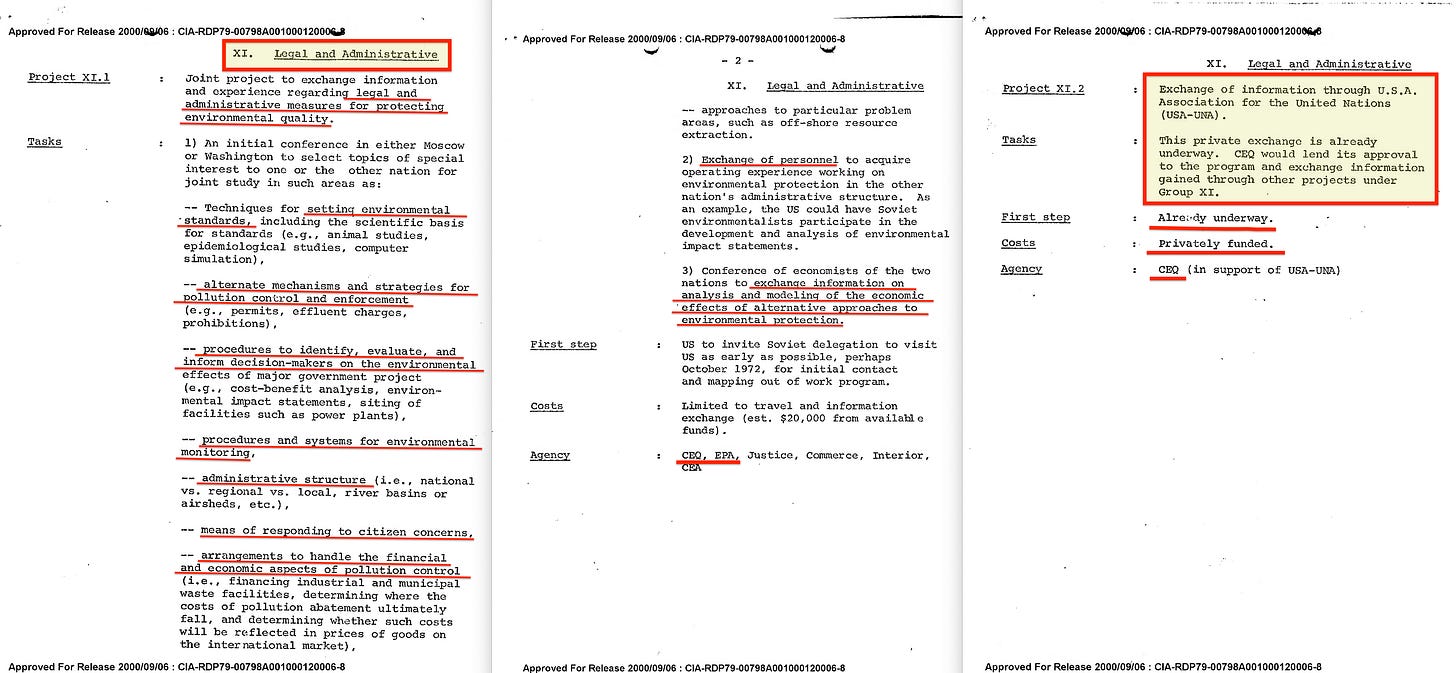

The US-USSR cooperation triggered a cascade of meetings and conferences, with the early sessions focused on building a shared foundation between the two new partners — including alignment on standards, instrumentation, measurement techniques, and modelling frameworks, all of which were also touched upon at the 1968 UNESCO Biosphere Conrerence. At first glance, the initial documents40 may seem procedural, but their legal and administrative content reveals ambitions far beyond technical harmonisation.

Beyond establishing scientific benchmarks and pollution enforcement mechanisms, the agreement sets out a far-reaching framework: administrative structures for joint governance, public consultation protocols, financial models for allocating pollution mitigation costs, and formal procedures to assess environmental impacts of infrastructure projects — closely resembling the Environmental Impact Statements introduced under NEPA in 196941, now foundational to regulatory42 oversight43.

Personnel exchange was another key feature, alongside joint modelling of the economic implications of various environmental strategies. Most notably, the documents indicate that the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) was already coordinating with the United Nations Association (UNA) — outside formal public oversight. Though framed as intergovernmental cooperation, this amounted to a privately funded, bureaucratically managed exchange — raising serious questions about the quiet role of private influence in environmental governance.

From the White House’s perspective, environmental cooperation with the USSR was presented not just as a diplomatic success, but as a pillar of Nixon’s broader détente strategy44. Though far less publicly emphasised than arms control such as the SALT Agreement of 197245, these environmental agreements were deeply embedded within the broader suite of bilateral ‘understandings’ forged during Nixon and Brezhnev’s meetings. While nuclear weapons treaties made the headlines, it was agreements like the U.S.–USSR Environmental Protection Agreement that quietly built the connective tissue of an emerging, converging administrative architecture.

In June 1973, Nixon and Brezhnev held high-profile meetings that produced treaties on nuclear war prevention, space cooperation, and peaceful uses of atomic energy. But nestled among these headline-grabbers was a web of scientific and bureaucratic frameworks — managed by figures like Russell Train and Yuri Izrael — aimed at legal harmonisation, data standardisation, and policy integration in environmental affairs. These weren’t symbolic gestures; they were institutional rehearsals for a post-ideological model of governance.

Most striking is how little public scrutiny this convergence received. The documents emphasise coordination, technical exchange, and ongoing bilateral meetings — but behind the briefings was a deeper ambition: to normalise U.S.–Soviet administrative alignment under the politically neutral banner of environmental stewardship. In that sense, the Nixon–Brezhnev summit was less a clash of systems than a handshake between planners. While Americans believed their government was holding the line against communism, it was quietly embedding Soviet-style long-term planning into the heart of environmental policy. Nixon’s environmental diplomacy was not a sideshow to détente — it was a gateway to the technocratic convergence that would outlive the Cold War itself.

While the 1972 Agreement laid the foundation, it was the bureaucratic machinery set in motion in 1973 that truly operationalized convergence. A July memo46 following the visit of Soviet environmental coordinator Yuri Izrael reveals just how structural this cooperation had become. Hosted by the CEQ and EPA, the visit focused not only on scientific exchange but on aligning technical standards, launching joint expeditions, scheduling symposia, and even coordinating public messaging through exhibitions. Most revealing was the Soviet proposal for a joint project on the economic aspects of pollution—embedding environmental metrics directly into economic planning, a hallmark of Soviet technocracy and a bridge to its Western counterpart.

Equally significant was the push for long-term reciprocity and fiscal parity in personnel exchanges—not for symbolic parity, but for budgeting and institutional symmetry. Izrael pressed for formalization of the ‘receiving side pays’ principle, embedding budgetary equivalence into a growing bilateral bureaucracy. As the memo shows, projects were subdivided, budgets negotiated, agendas synchronized, and field visits aligned—from permafrost zones to pulp plants. These were not isolated collaborations—they were the scaffolding of a shared operational model. Ideology was quietly subordinated to method.

Where the reports become more substantial is in the technical documents produced following each committee meeting47. These go beyond general cooperation and begin to codify specific areas of focus — particularly theoretical and experimental approaches to pollutant dispersion. The modelling dimension was made feasible by the late 1972 establishment of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), which became a central node for cross-border environmental simulations. Early work focused on sulphur compounds, which followed on from rising concerns around acid rain and ocean acidification — narratives largely driven by proprietary computational models, many of which were routed through or validated by IIASA.

One subtopic of note was transportation-related air pollution control. This extended naturally into the realm of vehicle emissions, and by implication, urban planning, traffic regulation, and long-term infrastructure modelling — each of which enabled deeper integration between environmental metrics and policy.

Water pollution soon followed48, with an emphasis on field studies across major river basins — particularly the Delaware and Ohio in the U.S., and the Seversky Donets in the USSR. But as with earlier efforts, the real focus was methodological: improving water planning frameworks and harmonising enforcement procedures. These technical exchanges were, in practice, vehicles for regulatory convergence.

Attention also shifted to lakes and estuaries, with the stated aim of developing predictive models for pollution levels based on population dynamics, hydrological conditions, and seasonal variation. The goal was a systems-level understanding of aquatic ecosystems — necessary groundwork for global monitoring and control.

By this stage, the ecological effects of pollutants were flagged as a central issue, with a symposium on whole-ecosystem impacts scheduled for 1974. Even agriculture entered the discussion — particularly through insect population studies — marking a shift toward managing biological variables within the same integrated environmental governance framework.

Further cooperation expanded into urban environmental management, with working groups focusing on pollution tied to poor planning, sewage systems, and waste disposal. The effort was framed as a technical exercise but carried long-term implications for how cities would be regulated under international environmental norms.

One of the more significant — and arguably controversial — topics soon emerged: the preservation of nature and the organisation of ecological reserves. Though mentioned only briefly in the original 1972 agreement, this area rapidly became central. At the same time, UNESCO launched its Man and the Biosphere Programme (MAB)49, laying the foundation for what would later become a global network of Biosphere Reserves50 and World Heritage Sites51 — mechanisms with deep regulatory reach under a banner of conservation.

On the U.S. side, CEQ’s Lee Talbot led the charge, coordinating a whole range of working groups. These included wild fauna and flora (with subgroups for endangered species management and preserve organisation), extreme ecosystems (from northern to arid zones), and even marine mammals as a standalone category.

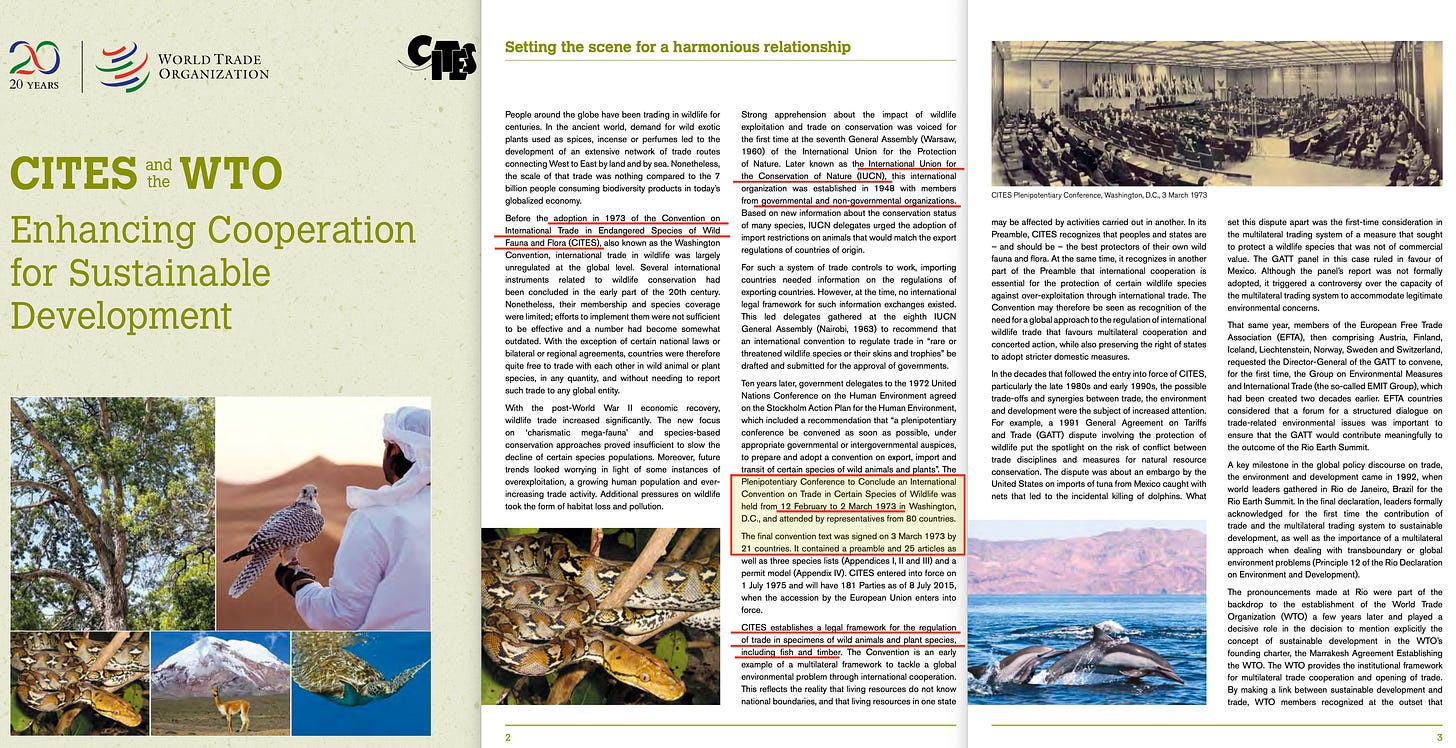

And it was here that the cooperation turned from technical coordination to binding law. In January 1973, U.S. and Soviet specialists convened in Washington to lay the groundwork for an international treaty on trade in endangered species. The outcome was the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES)52, which still governs global wildlife trade today — its roots, curiously, buried not in public debate but in the bureaucratic aftermath of a Cold War environmental treaty.

While the IUCN’s work in this area had been underway for some time, developments elsewhere followed a slightly different trajectory:

Also at the October meeting considerable progress was made towards a biletaral Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Birds, with the possibility of expanding the convention’s coverage to other species and to endangered habitats.

This may seem like a narrower topic, but it laid the groundwork for something much larger. The resulting treaty — the 1976 Conservation of Migratory Birds and Their Environment53 — served as the primary precursor to the 1979 Bonn Convention, which would eventually form the backbone of international frameworks for species and habitat protection under transboundary governance54.

And this, in turn, served as an ideological precursor to the U.S. Strategy Conference on Biological Diversity, held in November 198155 — itself a stepping stone toward the Convention on Biological Diversity, formally adopted at the 1992 Rio Earth Summit. The 1981 conference expanded upon the targeted approach of the 1976 Convention on Migratory Birds by broadening the focus to biological diversity more generally, emphasising the need for international cooperation in protecting species and ecosystems.

Next came the issue of marine pollution, primarily relating to oil spills and similar incidents — with the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill56 still fresh in the public’s memory and undoubtedly influencing the urgency of the discussions.

But in classic technocratic fashion, the definition of ‘marine pollution’ quickly expanded far beyond its traditional shipping-related context. A second working group emerged — focused not on marine activity per se, but on pollution tied to land-based and offshore oil operations. This broadened the term into a catch-all for industrial and resource extraction impacts, embedding oil infrastructure management directly into environmental cooperation.

According to the October 7, 1973, working group report signed in Moscow, the scope of ‘marine pollution’ now included sand control during drilling, oil spill response, personnel training, corrosion protection, blowout prevention, and pipeline monitoring. Wastewater treatment, oil transport, and even regulatory practices for offshore development were absorbed into the environmental agenda.

The reclassification didn’t stop there: the group moved to include environmental safeguards for onshore oil field development — significantly stretching the definition of ‘marine pollution’ while simultaneously legitimising industrial oversight as environmental protection.

The section on the ‘biological and genetic consequences of environmental pollution’ similarly saw a sharp expansion in scope. What began as a discussion of pollutants was transformed into a sweeping mandate for ‘comprehensive environmental management of an identified region’. Explicit attention was given to ‘interactions between man and his environment’, with emphasis on municipal, industrial, and agricultural activity. This wasn’t mere mission creep…

… it was the establishment of a framework with the capacity to justify intervention in nearly every domain of human life.

Under this heading, biological impacts ballooned into categories such as mutagenesis, radiation exposure, epidemiology, and environmental health science. Sampling environmental toxins was no longer enough — joint teams now aimed to monitor populations for cell-level damage from pollution. The shift toward global bio-surveillance was unmistakable.

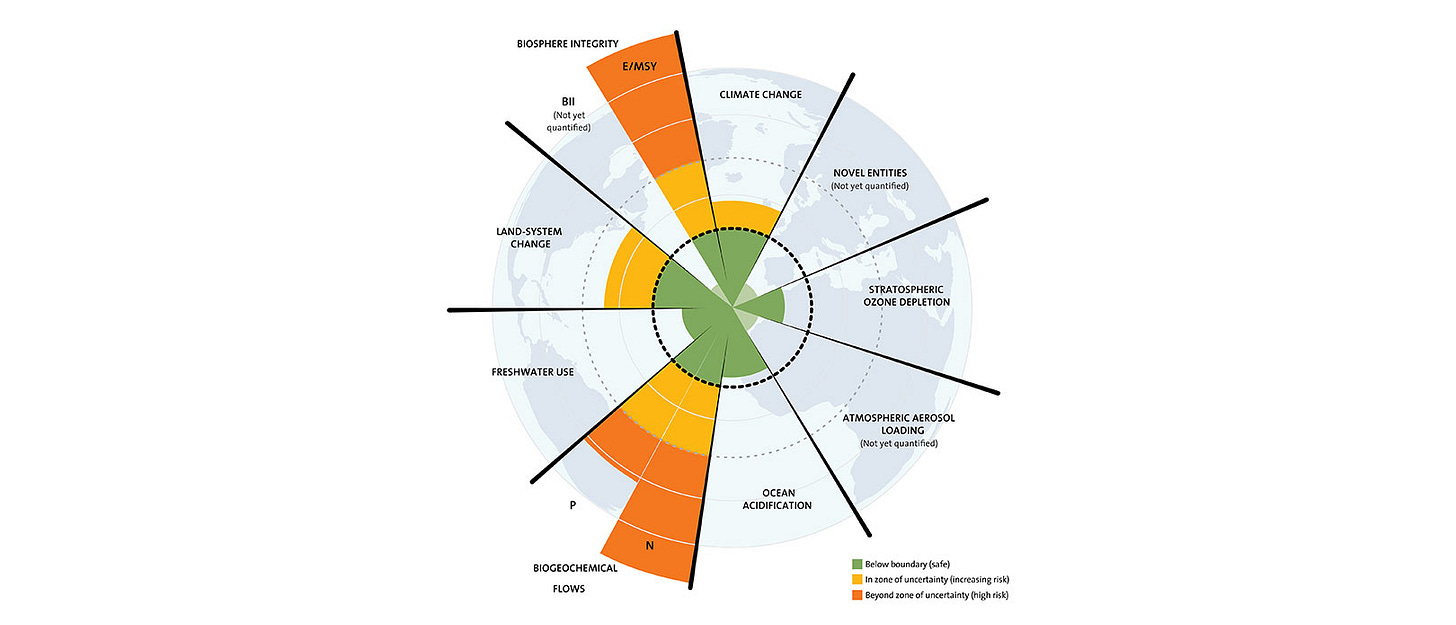

Climate change, too, was pulled into this widening agenda. What started as a limited study of atmospheric effects evolved into a call for a global monitoring network for trace air pollutants. The working group launched early climate modelling efforts and proposed a historical climate database. Terms like ‘boundary conditions’ were used — a precursor to today’s Planetary Boundaries framework. To ensure data continuity, all stations and equipment were to be harmonised through intercalibration — the first steps toward globally integrated environmental surveillance.

Finally, even earthquake prediction was absorbed into the program, repackaged as seismic activity monitoring, with a call for expanded computational modelling of seismic risk. The scope was widened further to include tsunami forecasting, through the integration of U.S. and Soviet early warning systems — signalling that by this stage, environmental cooperation had grown into a full-spectrum surveillance and modelling architecture, stretching from atmosphere to biosphere to lithosphere.

Arctic and subarctic ecosystems were also slated for integration — though, true to form, they weren’t treated as standalone priorities, but instead absorbed into other segments of the programme. The approach was not one of isolation, but of embedding environmental control across all geographies, reinforcing the logic of total systemic integration.

And finally came the legal and administrative measures, arguably the most consequential. These included an explicit focus on:

The working group agrees upon the major areas for future study, as follows: (1) Questions of developing legislation… (6) exchange of information on legal measures and mechanisms and the system of legal responsibility in the area of environmental protection, including specific inividual components of the agreement (e.g. land use, water law).

What this amounted to was nothing less than a synthesis of environmental legislation between two ideologically opposed superpowers — one capitalist, the other socialist — under the banner of ‘cooperation’. To facilitate this harmonisation, a structured exchange of legal experts was proposed, explicitly involving Russell E. Train on the American side and Academician Fedorov on the Soviet side.

This was no minor bureaucratic detail. Fedorov’s keynote at the 1979 First World Climate Conference opened with a pointed criticism: the United States lacked a clear national objective. In agreement was Ervin László, the same man who, just two years earlier, had published Goals for Mankind through the Club of Rome57 — a text that explicitly called for the redirection of global society through long-term planning, systems analysis, and coordinated technocratic oversight.

The implication was unmistakable: without a unifying, technocratically-defined purpose, the United States — and Western liberalism more broadly — was unfit for the kind of top-down, systemic governance that this new international order demanded.

And overseeing this entire process? The document bears the unmistakable signature of Henry Kissinger — a man who, in this context, didn’t merely negotiate with the Soviets, but brokered the quiet convergence of Soviet-led socialism and American-led capitalism, all under the guise of environmental stewardship.

What the May 23, 1972 U.S.–USSR Agreement on Environmental Protection ultimately represented was not cooperation — it was strategic convergence masquerading as science. Behind the language of clean air, wildlife, and climate modelling lay a sprawling apparatus of policy alignment, legal harmonisation, and administrative integration. The agreement expanded into dozens of subfields — from air and water pollution to migratory species, onshore oil development, genetic surveillance, and even earthquake prediction. Each category functioned as a gateway — pulling U.S. institutions into joint standard-setting, shared databases, parallel legislation, and mutual enforcement regimes. This wasn’t diplomacy. It was quiet annexation — of structure, of method, of sovereignty.

And for the American voter, it was a fundamental betrayal. The Cold War had always been framed as a battle between two opposing systems: individual liberty and centralised control. But this agreement didn’t merge them — it rendered their difference irrelevant. By embedding Soviet-style planning into Western environmental policy — and by using that apparatus to justify increasingly centralised governance — the agreement embraced and extended the democratic model until it became functionally indistinguishable from its supposed opposite. No vote was cast. No debate was held. And yet, through metrics, modelling, and managed sustainability, the United States began aligning itself to a globalist administrative order — not through conquest, but through consensus engineered behind closed doors.

That signature sealed not just a treaty — it marked the quiet erosion of the very model it claimed to protect. It was carried out through surveillance data gathered by the NRO and other intelligence-linked networks, research produced by the International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU), and the modelling work of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) — later applied directly in the context of climate forecasting through the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). All of this rose in tandem with the development of UNEP’s Global Environment Monitoring System (GEMS) — a programme which, by 1984 according to the IUCN, had expanded to include 30 separate datastreams, and which by 1985 had established a global surveillance database via UNEP GEMS/GRID. Among the earliest streams were GEMS/AIR and GEMS/WATER, with epidemiology already integrated as a core focus by 1974.

Environmental monitoring had quietly become human monitoring — and with it, the infrastructure for technocratic global governance began to harden into place.

When the invite-only, ICSU-arranged First World Climate Conference convened in 1979, the emphasis wasn’t on validating the science — which is telling, given that even Bert Bolin, one of its leading figures, had openly admitted in 1976 that beyond CO₂ being plant food, they knew very little. By 1978, an IIASA working group had quietly conceded that they understood less about the global carbon cycle than they had believed a decade earlier — especially given the near-total absence of data on the oceanic cycle, the system’s largest component by far.

Instead, the conference’s focus was entirely policy-driven — centred on agriculture, oceans, atmospheric systems, and institutional coordination. These priorities closely mirrored the working group agenda formalised through the 1972 U.S.–USSR environmental agreement. Despite the lack of reliable data and erratic temperature trends, alarmist projections dominated the narrative. But by this point, the real machinery had already been constructed: satellite surveillance, global data infrastructure, and the bureaucratic frameworks to manage it. By the time of the Second World Climate Conference, the agenda had escalated again, with an explicit push for satellite-based surveillance and full GIS integration — revealing that the concern was never solely about climate.

It was always about control.

A declassified 1974 CIA memorandum58 further reveals that early U.S.–Soviet cooperation in the area of water resource planning — a designated subfield of the 1972 environmental agreement — was far less about scientific collaboration and far more about Soviet access to U.S. technology and systems design. The Soviets, it noted, were actively seeking an ‘automated total water resource program similar to that in the US’, placing particular emphasis on drainage, salinity control, river basin diversion, and computerised planning models.

Though U.S. officials downplayed any loss of sensitive information, the memo quietly admits that Soviet counterparts were gaining valuable insights not just through scientific exchanges, but through exposure to the entire architecture of American environmental systems management. In short, the partnership served as a strategic window into how the U.S. governed complex ecological and resource systems — with long-term implications for convergence at the operational level.

By 1974, it had become clear that the U.S.–USSR Environmental Protection Agreement was never simply about ‘cooperation’ — it was about constructing a post-ideological governance model. A series of CIA-monitored technical exchanges59 reveals a stunning breadth of integration, covering everything from stack gas modelling and river basin planning to desulphurisation, bio-monitoring, and even vehicle emissions control. What emerged wasn’t just alignment on environmental standards, but the consolidation of a shared administrative grammar — a language of technocratic coordination that quietly superseded the Cold War binary.

The East and West weren’t merging ideologies; they were rendering them obsolete under the weight of an all-encompassing systems architecture.

Across dozens of project areas — including air, water, agriculture, energy, and urban development — the agreement served as a gateway for harmonising everything from instrumentation to enforcement mechanisms. U.S. expertise flowed into Soviet industrial infrastructure, while Soviet models influenced U.S. regional planning strategies. Scientific exchange was the visible layer, but embedded underneath was the creation of shared feedback loops, coordinated modelling systems, and legal harmonisation. The agreement facilitated parallel structures across institutions, bringing into sync two opposing administrative regimes.

This convergence was not ideological — it was procedural. Under the guise of environmental stewardship, the two powers laid the groundwork for a managerial global order. Even sensitive domains like mutagenesis, toxicology, and atmospheric modelling were folded into the agreement’s purview. Data streams became the universal translator, with surveillance, standardisation, and modelling as the tools for governing both nature and man. And as CIA analysts quietly observed, Soviet planners were especially keen to replicate the U.S. system’s automated environmental planning machinery — including the very structure of NEPA-style environmental impact assessments.

And an internal CIA document60 functions as a meta-overview of all existing U.S.–Soviet bilateral agreements up to that point. Its tone is clinical, but the sheer breadth of domains it covers — from environmental protection to agriculture, medical research, and energy — illustrates the extent to which the bilateral framework had already matured into a systemic convergence platform by the early 1980s. What’s particularly notable is that environmental protection is listed as one of the pillars, alongside industrial and technological cooperation. This classification implies that environmental agreements weren’t just symbolic or soft-diplomacy measures — they were part of the core operational structure of Soviet-American détente. The environment was not a side issue, but a vector of integration.

Lynton K. Caldwell, architect of NEPA and pioneer of systems-based environmental governance, laid the foundation with Man and His Environment, which reframed ecological issues as matters of administrative logic and scientific control. His work introduced a model of environmentalism not as advocacy or conservation, but as a framework for societal reorganisation — with bureaucracies, legal structures, and education systems tasked with systematically managing human–environment relations. This ideological base was radicalised further in the 1974 anthology Environment and Society, where Caldwell returned alongside contributors like Ian McHarg to openly propose cultural reprogramming under the guise of ‘values realignment’. The volume pushed Spaceship Earth thinking, Proletkult-style ethics, and systems theory as a moral imperative — framing population control and behavioural conditioning as scientific necessities. People like Maurice Strong and institutions such as ICSU and SCOPE helped propagate these ideas globally, embedding them in UN policy frameworks through UNESCO, UNEP, and IUCN, all backed by Rockefeller and Ford Foundation funding and media alignment.

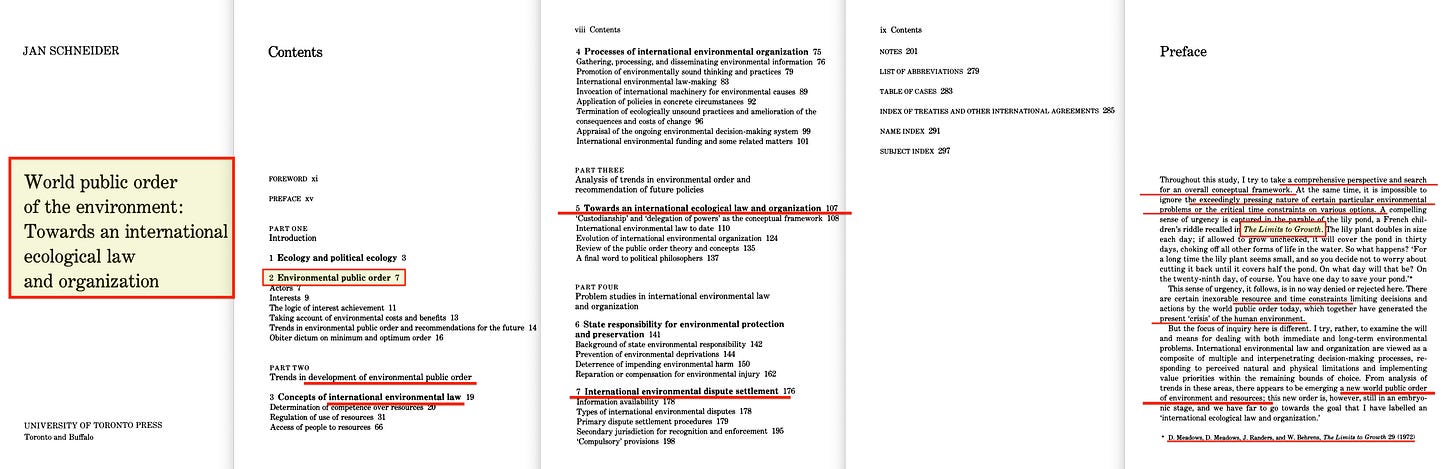

The administrative mechanism followed soon after. With Nixon’s 1972 signature — orchestrated by Henry Kissinger and carried out by Russell E. Train — U.S.–Soviet environmental cooperation launched a real-world convergence project that rapidly expanded into joint modelling via IIASA, global surveillance through UNEP’s GEMS and GRID systems, and legal harmonisation confirmed in CIA and State Department documents. The machinery was no longer speculative: sub-agreements on migratory birds, Arctic ecosystems, and endangered species enforcement (like CITES) provided concrete examples. Jan Schneider’s World Public Order of the Environment (1979) codified this into a legal theory of environmental global governance.

Crucially, as GEMS incorporated epidemiological data streams into its expanding global monitoring framework, parallel developments in U.S. domestic health planning emerged. The alleged 1976 Swine Flu episode — itself marked by media panic and policy overreach — catalysed the creation of the first formal pandemic response plan in 1978. This mirrored the same systems logic: anticipatory modelling, centralised coordination, and administrative pretext for behavioural control. Environmental surveillance and public health were converging under a unified architecture of pre-emptive governance. And this initiative soon spread across the Atlantic.

And a final 1972 White House memorandum61 reveals just how carefully controlled this process was. Henry Kissinger explicitly instructed Russell E. Train to initiate exploratory environmental talks with Soviet officials — but under strict conditions: ‘There should be no public announcement or discussion of your exploratory talks with the Soviets’. Far from transparent diplomacy, this was a tightly choreographed operation across the Departments of State, Defense, Commerce, and Interior — with full presidential oversight and zero democratic input. Environmental cooperation was the storefront; beneath it lay the architecture for post-ideological governance, constructed quietly, system by system.

And as soon as that dotted line was signed, it was drowned out by the noise made by the SALT Agreements, and the 1972 Stockholm Conference.

By 1979, the global surveillance and modelling infrastructure — envisioned in SCOPE’s early reports and physically implemented through GEMS and IIASA — had reached operational maturity. That year’s invite-only World Climate Conference, convened by the WMO in collaboration with UNEP and ICSU, marked a pivotal narrative shift: it was not a validation of science, but a declaration of urgency. Despite open acknowledgements from figures such as Bert Bolin that climate science remained incomplete, the conference projected climate risk as an imminent global threat — one demanding coordinated international action, predictive modelling, and long-term socio-political planning.

In essence, the surveillance framework was in place, the data streams were live, and now, the call to action had arrived. The groundwork of SCOPE had established the structure; GEMS was building the apparatus; and the World Climate Conference supplied the political imperative to activate it.

It was against this backdrop that Jan Schneider’s World Public Order of the Environment62 (1979) emerged — not as abstract theory, but as the definitive legal and philosophical articulation of what the U.S.–Soviet environmental convergence had already set in motion. Published the same year, Schneider’s work offered a comprehensive blueprint for transforming environmental cooperation into a binding supranational legal regime. Far from hypothetical, it laid bare the mechanisms through which environmental law could — and should — replace national sovereignty with global governance. In Schneider’s view, ecological degradation was not merely a scientific issue, but a justification for reconfiguring the entire structure of governance.

At the heart of his thesis lies the concept of public order — a phrase historically reserved for justifying wartime intervention or international sanctions, now repurposed for ecological administration. Environmental law, he argued, should not be an extension of state policy, but its governing framework — shaped by systems analysis, enforced through treaties, and legitimised via scientific consensus. Governance would no longer derive from democratic will, but from the imperative of planetary management.

What’s particularly remarkable is Schneider’s repeated emphasis on U.S.–Soviet cooperation as the prototype for this new global order. Their shared working groups, harmonised legislation, and joint modelling efforts were not anomalies — they were the early form of a new administrative paradigm, in essence enabled by the 1972 treaty. The instruments of convergence were already in play: IIASA for modelling, GEMS for surveillance, UNESCO for policy alignment, and environmental law as the binding mechanism. Schneider’s book did not anticipate the system — it merely retold the story of what had been quietly built beneath the surface.

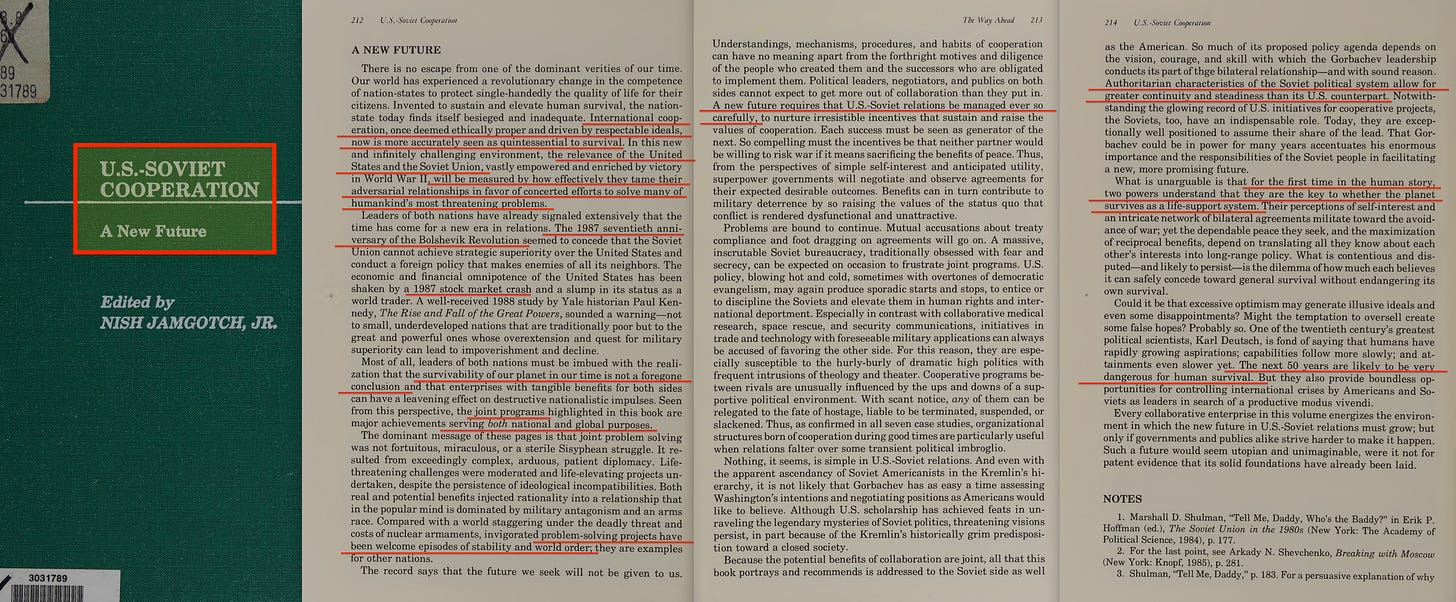

A decade later, the implications of Schneider’s vision were no longer confined to academic theory. U.S.–Soviet Cooperation: A New Future63, published in 1989, provides a retrospective—which at times appears almost celebratory—account of how these ideas had been carried into practice. Nish does not ask whether convergence should occur; he assumes it already has, and focuses instead on how to deepen and expand it. Environmental cooperation is framed not as soft diplomacy, but as a hardened, institutionalised mechanism through which the two former superpowers had begun to synchronise their policies, procedures, and long-term planning objectives.

What’s striking throughout the book is how much of the original 1972 framework had already matured. Contributors discuss the joint development of regional planning models, unified environmental metrics, and standardised monitoring techniques. Education, health, and agricultural policy are all shown to have been drawn into the same integrated structure. Surveillance data is treated as a shared resource. Modelling outputs are cross-validated between institutions. International exhibitions and public education campaigns are harmonised to ensure alignment in messaging. The convergence was no longer covert—it had simply become the administrative baseline.

At times, the tone borders on triumphant. The very logic that underpinned Schneider’s 1979 legal framework is now treated as common sense: that sovereignty must yield to science, that environmental risks justify administrative override, and that technocratic planning offers the only viable solution to global complexity. What was once a controversial proposition—that global environmental administration could supersede political ideology—had, by 1989, become policy mainstream.

U.S.–Soviet Cooperation: A New Future marked the final handoff: from covert coordination, to explicit legal framing, to full institutional adoption.

The circle was complete.

In the broader context — much like the 1968 UNESCO Biosphere Conference corresponded with the 1992 Rio Earth Summit — these two volumes function as historical bookends: World Public Order of the Environment provides the legal rationale, and U.S.–Soviet Cooperation confirms its institutional realisation. Together, they document the transition from treaty to technocracy, from Cold War opposition to procedural unity, and from democratic accountability to administrative consensus. Far from isolated artefacts, these books reveal that the systems constructed in the shadows of the 1972 agreement were not only real — they were meant to endure.

If Schneider and the U.S.–Soviet institutional apparatus established the machinery, then Mikhail Gorbachev’s 1987 speech, To Feel Responsible for the World’s Destiny64, offered an ideological green light. Delivered during the 70th anniversary of the October Revolution, the address did more than just echo the logic of environmental convergence — it resurrected the framework of Lenin’s New Economic Policy (NEP), repurposed for global governance. Gorbachev argued that socialism — and by extension, the administrative methods honed under the NEP — was the only system capable of managing modern planetary crises. The Cold War binary, he insisted, had to give way to a unified planetary consciousness, driven by shared ecological threats, technological interdependence, and the imperative of ‘a new way of thinking’.

The structural parallel is striking. Lenin’s NEP introduced a mixed-economy model in which private enterprise operated under overarching state-defined objectives — with the Communist Party deciding the ‘common good’. Gorbachev’s perestroika mirrored this logic, but updated it for the global stage: rather than the Party, it would now be civil society organisations (CSOs), international NGOs, and multilateral institutions that would define the public interest. This aligns precisely with the governance model later formalised in Agenda 21, where policy direction is guided not by democratic mandate, but by multi-stakeholder consensus between governments, corporations, and CSOs — a public–private fusion replicating the NEP's architecture under new branding.

Gorbachev’s additional remark — that glasnost and perestroika would eliminate the perceived Soviet threat — effectively removed the last obstacle to global administrative integration. With the ideological clash resolved, environmentalism became the neutral justification for governance realignment. He even framed militarism as a diversion from ecological responsibility, proposing that arms budgets be redirected toward planetary stewardship. His declaration that ‘we are all in the same boat’ was no casual metaphor. It was a coded affirmation of the very convergence model being implemented — one where sovereignty would yield to supranational planning, and the ‘common good’ would be defined not by citizens, but by the institutions appointed to speak on their behalf, with institutions such as the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) — in the context of ‘planetary stewardship’ — having already positioned itself as a global moral and administrative authority over nature and, by logical extension, humanity.

This model — in which supranational institutions defined and administered the ‘common good’, first outlined by Leonard S. Woolf in the 1916 Fabian Society report International Government — was no longer speculative. By the late 1980s, it had been legitimised rhetorically by Gorbachev and operationalised institutionally by actors across both East and West. The next logical step was not deeper integration — it was monetisation.

To fully capitalise on the institutional architecture laid out during the 1970s and 1980s — particularly through the U.S.–USSR environmental convergence framework — the Rio Earth Summit in 1992 marked a decisive transition from blueprint to balance sheet. While Rio is often remembered for launching the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), what often goes overlooked is how these frameworks were swiftly backed by financial instruments designed to commodify the new system of environmental governance.

Enter UNCTAD — the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development — which, in the same year as the Rio Summit, released the first of two reports titled Combating Global Warming. This report, followed by a 1994 companion volume, established the financial logic behind global environmental policy. Together, these documents constructed the market architecture necessary to monetise carbon emissions, define emission entitlements, and develop protocols for carbon sequestration through land-use controls — all of which mapped precisely onto the legal and institutional frameworks built by the decades of prior treaties, modelling systems, and surveillance infrastructure.

Where Rio laid the normative groundwork and created the institutional bodies (UNFCCC and CBD), UNCTAD operationalised their economic function. The transformation was now complete: from ideology to administration, from administration to enforcement, and from enforcement to financialisation. Carbon, biodiversity, and ecosystem services had become assets. And behind the façade of environmental concern stood a decades-long strategy to reorganise global governance through technocratic convergence — now bankable, tradable, and enforceable. The Global Environment Facility (GEF) was expressly created for this purpose, originally proposed at the Fourth World Wilderness Congress in 1987 under the working title of a ‘World Conservation Bank’.

In retrospect, the 1972 U.S.–USSR Agreement on Environmental Protection did not merely initiate environmental cooperation — it quietly orchestrated the convergence of two seemingly opposed ideological systems into a single, supranational technocratic regime. While the world remained occupied by Cold War posturing and the staged collapse of the Iron Curtain, a far more consequential transformation was unfolding in the background: the procedural fusion of socialism and capitalism under the neutral banner of planetary stewardship.

This was not an ideological surrender, nor a triumph of one side over the other. It was the construction of an entirely new administrative paradigm — one that subordinated both ideologies to systems governance, environmental metrics, and bureaucratic consensus. From shared modelling infrastructure at IIASA to harmonised legal structures and surveillance systems, the architecture of global governance was laid without a shred of public debate or democratic mandate.

The treaty’s legacy was not a treaty at all. It was the deceptive operationalisation of a world order in which sovereignty was replaced by politicised science, policymaking was outsourced to planners, and governance became the exclusive domain of those who claimed to speak for ‘the planet’. The Cold War did not end in victory — it ended in synthesis. And through this quiet convergence, the foundational institutions of liberal democracy were reprogrammed to serve an entirely different logic:

Technocratic, planetary management.

I want to thank the writers who compile and share this information. It's overwhelming, but I try to stay up with it. I have felt for most of my life that the control mechanism has been trying to take over EVERYTHING for their purposes and I resist by sharing what I can with the few that will listen. May you all live long and prosper!

This is fantastic research it goes right in line with my research and my book The Sleeper Agent: The Rise of Lyme Disease, Chronic Illness, and the Great Imitator Antigens of Biological Warfare. All of these 1972 agreements were a betrayal to America and putting us in enemy hands. A lot of people dismiss my book for bringing up Russia and the Soviet Union but they were very important players in this whole UN and globalization agenda. In 1954 we allowed Albert Sabin of the US Public Health System to team up with a hardcore Stalinist bioweaponeer from the USSR named M. P. Chumakov to create the oral polio vaccine, and Chumakov also worked to some degree with Jonas Salk, and of course both vaccines were contaminated with the cancer virus SV40. Then fast forward to today I showed how M. P. Chumakov's son Konstantin Chumakov landed a position leading vaccine safety and review at the FDA and approved the COVID-19 vaccine! Anyway, this was a great article thank you for this amazing work!