Arthur Schlesinger Jr. is often remembered as Kennedy’s court historian, but he also played a strategic role in covert planning. As early as 1961, he was advancing frameworks for supranational governance built on stakeholder management and tripartite coordination. Drafts by CIA operative Dana B. Durand1 confirm a model in which civil society, state actors, and intelligence intermediaries shaped policy — not through elections, but by expert consensus.

This is a continuation of yesterday’s substack post.

The trajectory is documented, not least by Stan Draenos, in whose book on Andreas Papandreou2 he details not only the ‘International Study Group on Freedom and Democracy’ being the brainchild of Schlesinger, but he further details Dana Durand harbouring left-wing tendencies — comparable to that of Amory and Schlesinger. And that’s of interest, because it was Durand who penned the material on the ‘World Congress for Freedom and Democracy’ pushed by CIA DD/I, Robert Amory, Jr.

Naturally, this is all framed around being ‘anti-communist’, but technically, ‘ethical socialists’ such as the Fabian Society too are ‘anti-communist’ — not because they disagree with the end objective, but rather the route to get there.

Schlesinger’s efforts were not isolated. He worked with a transatlantic intellectual network that included ‘social democrats’ and other socialists across Europe3. He conversed with people involved in drafting the federalist Ventotene Manifesto4, and his presence at international conferences was mirrored by contemporaries like Roger Hilsman (a Rockefeller Fellow56). These were not random friendships; they formed an ideological bedrock for a new kind of internationalism — one that rejected Westphalian sovereignty in favour of managed interdependence, guided by ‘expert panels’ controlled by the technocratic elite. The 1961 proposal for the World Congress — framed around civic engagement and anti-communist unity — was in fact a cover for reframing liberal democracy itself, replacing representative politics with issue-specific governance led by NGOs, backed by foundation funding, and promoted by compliant mainstream media programming.

Anthony Carew’s 1993 book on Walter Reuther7 — the civil rights activist who transformed the UAW into a progressive, internationalist labour organisation — corroborates Stan Draenos’s account while furnishing deeper insight into the American operational side. Carew reveals that the World Congress initiative was not an isolated proposal but one node in a broader transatlantic agenda involving Reuther, Arthur Schlesinger Jr., Hubert Humphrey, and Altiero Spinelli. The goal was to forge a new political alignment uniting liberals and the non-communist left across national boundaries. The idea was advanced through groups like the International Study Group on Freedom and Democracy, a structural prototype for post-democratic governance, wherein unions, NGOs, and civil society would coordinate policy outside of electoral legitimacy. Carew further notes that the entire framework rested on a now-commonplace assumption among American elites: that the differences between capitalism and social democracy were dissolving.

Piero S. Graglia8 sheds further light on the affair, offering an Italian perspective on Altiero Spinelli and — beyond detailing the oh-so-predictable foundation funding — adds clarifying detail about the Il Mulino group, which we saw elsewhere in relation to Schlesinger. It confirms Schlesinger’s attendance at the April 25, 1961 Bologna meeting, where the idea of a ‘democratic international’ was discussed, that would unite democratic actors from across the Western world under a structure resembling what we in contemporary terminology call stakeholder governance.

Graglia notes that Spinelli, during his early 1960s U.S. trip, met not only with Schlesinger but also with Henry Kissinger, Dean Rusk, Walter Rostow, and other key figures linked to American foreign policy and intelligence. The initiative was supported by foundation-connected networks such as the Ford Foundation, 20th Century Fund, and the Carnegie Endowment, and its advance was aided by a ‘massive lobbying campaign’ involving letters to high-level U.S. officials — including staff at the State Department and CIA-linked interlocutors like Dana Durand.

The ‘World Congress’ proposal was meant to receive full White House support in January 1962 — around the time the CIA was cleaning house, with Amory leaving only months later. Spinelli — with help from the Il Mulino group — had coordinated efforts to present the initiative as a ‘democratic international’ aligned with American Cold War objectives. Dana Durand prepared a draft declaration titled Freedom and Democracy: A Declaration of Principles, and submitted a proposal intended to elicit direct backing from the Kennedy administration. Durand’s memo to Allen Dulles dated October 3, 1961, supports this, and further evidence indicates that the CIA’s deputy director of intelligence formally acknowledged the plan in January 1962, noting the agency’s interest in potential long-term benefits to both the U.S. and the ‘Free World’. The initiative was not aimed at deepening democratic representation per se, but at reconfiguring it — away from electoral sovereignty and toward stakeholder-based governance coordinated through elite transnational networks.

However, by late 1961, the political-institutional dimension of the project had already begun to disintegrate. Internal tensions and questions about Spinelli’s authority over the process stalled momentum. Nonetheless, the Ford Foundation proceeded to back a related initiative: the International Affairs Institute (IAI), which formally emerged from the ashes of the earlier effort under the acronym IRPDI. The CIA, according to internal memoranda, considered the entire process part of a broader political orientation and influence strategy, calibrated to replace national sovereignty with transnational consensus.

Of further note, the December 1961 meeting also included Edgar Morin whose later involvement with the Groupes des Dix — a group focused on exploring the connection between science and politics through the lens of General Systems Theory and Cybernetics — eventually developed into the Collegium International in 20029.

Incidentally, the medium through which the Collegium International later found a bridge between science and politics was ethics.

Finally, the essay includes an important detail:

… it is not difficult to notice then that Hirschman’s main theory, the theory of unbalanced growth aimed precisely at developing countries, overlaps with the attempts to renew the democratic idea carried forward at the beginning of the 1960s by the Mulino group and Spinelli.

… it’s probably worth investigating these two characters.

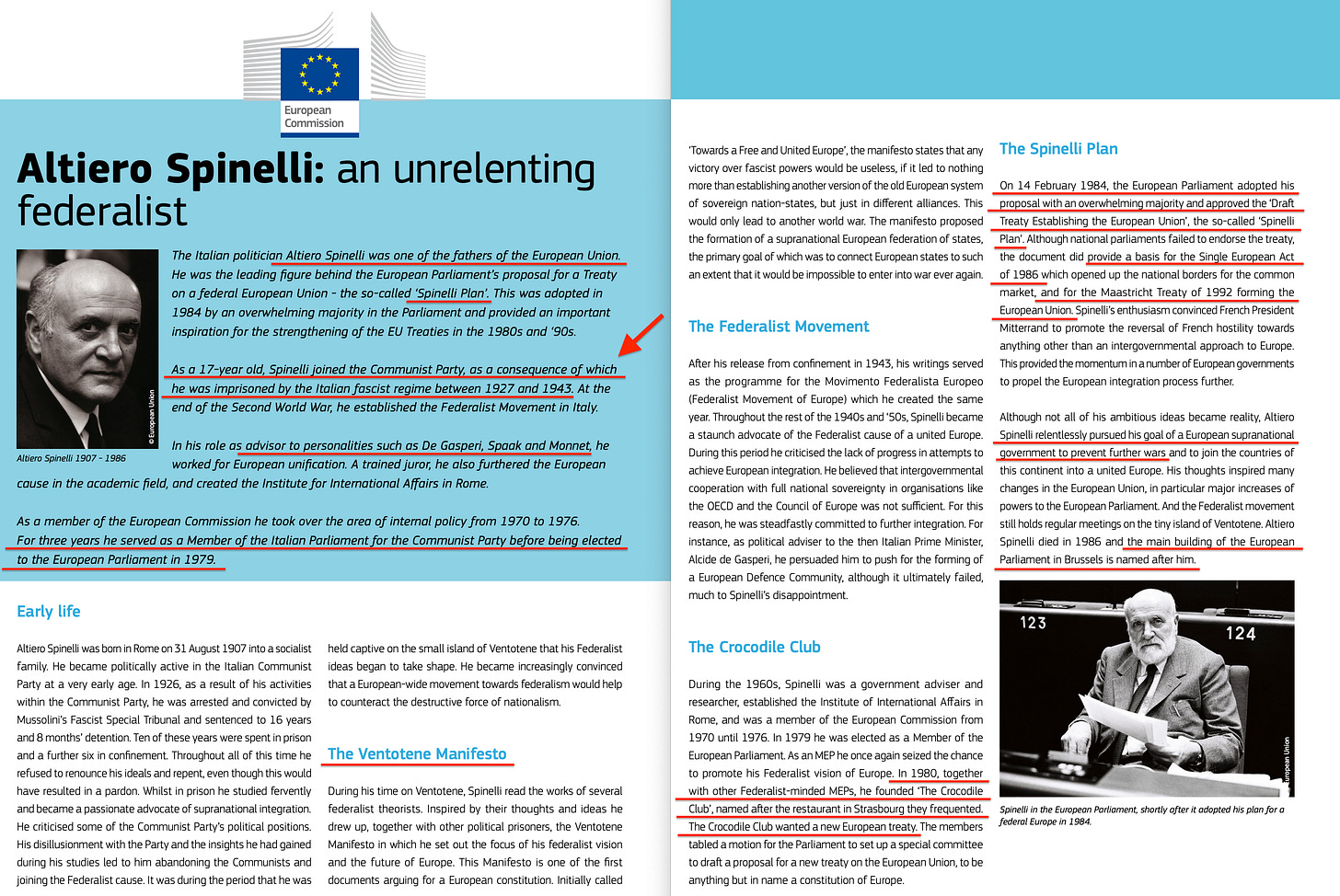

Momentarily setting aside Hirschman, here’s Spinelli10:

The Italian politician Altiero Spinelli was one of the fathers of the European Union. He was the leading figure behind the European Parliament’s proposal for a Treaty on a federal European Union - the so-called ‘Spinelli Plan’. This was adopted in 1984 by an overwhelming majority in the Parliament and provided an important inspiration for the strengthening of the EU Treaties in the 1980s and ‘90s.

Spinelli came up with the ideas leading to the Maastricht Treaty aka the European Union. And what else can be said about him?

As a 17-year old, Spinelli joined the Communist Party, as a consequence of which he was imprisoned by the Italian fascist regime between 1927 and 1943. At the end of the Second World War, he established the Federalist Movement in Italy.

He was a full-blown communist in his earlier life. But at least that was only during his youth, right?

As a member of the European Commission he took over the area of internal policy from 1970 to 1976. For three years he served as a Member of the Italian Parliament for the Communist Party before being elected to the European Parliament in 1979

Wait, no — he was a member of the Italian communist party, immediately prior to him entering the European Parliament in 1979!

As for Hirschman, his Theory of Unbalanced Growth11 relates to a strategy of prioritising third world investment with a few selected, key enterprises. This, then, logically creates a cushy job for some ‘expert’ to determine which enterprises are worthy (while his foundation buddies are given a heads-up ahead of time no doubt).

Consequently, Schlesinger’s ideological orientation — with contemporaries like Fulton Lewis Jr12 labelling him a ‘hyper-liberal’ — was not merely progressive in the domestic sense, but in the geopolitically utopian. He saw democratic legitimacy not as a product of consent, but as something to be globally engineered through institutions aligned with universal moral goals — though you can call it social justice if you prefer. His defence of Robert Amory Jr. after the Bay of Pigs was an attempt to preserve the emerging foundation of this vision, as Amory wasn’t only instrumental in systems-based intelligence but further through his internal promotion of the World Congress inself. Together, their work aimed to fuse intelligence, academia, and civil society organisations into a seamless global architecture — a vision decades later fully realised through the United Nations and specifically, with the Sustainable Development Goals stating what exactly the ‘common good’ truly meant from an ‘ethical’ perspective.

This context also explains Schlesinger’s tolerance of CIA manipulation of civil society. Schlesinger didn’t consider it a betrayal of liberalism, but rather a useful mechanism to establish his definition thereof. The CIA was slowly being positioned as the steward of ‘democratic values’ via controlled civil society organisations. Schlesinger's writings — particularly his post-Kennedy works — reveal a consistent thread: democracy needed to be saved — from itself. The ‘freedom’ he sought to protect was not constitutional, but an ethical freedom to be enforced by experts such as those promoting the SDGs — and certainly not those of democratic representatives.

Thus, the World Congress for Freedom and Democracy was less of an outlier, but rather an early prototype of the global frameworks that would emerge decades later under the banners of multistakeholderism, sustainable development, and ‘Good Governance’. That the proposal was co-authored by a CIA operative —Dana Durand — only confirms what Schlesinger’s intellectual trajectory had long suggested: the project of postwar liberalism hid a covert drive to lay the groundwork for a post-democratic international order, led not by nations but by networks funded by large foundations. And Karl Mundt’s Freedom Academy — a manipulative effort to mirror Soviet intelligence infrastructure within the United States — is further evidence of these consistent attempts to subversively manipulate Western nations.

By the mid-1970s, the covert architecture brewing within the U.S. national security apparatus had fully materialised. A pivotal moment came in January 1968 during a confidential Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) seminar on intelligence and foreign policy13. There, former CIA Deputy Director Richard Bissell openly outlined a dual model of covert operation: intelligence collection and covert action. But it was his eight-point framework for political intervention — including the covert financing of parties, labor unions, media, and paramilitary operations — that revealed just how deeply strategic manipulation had been formalised within elite circles, all under the guise of foreign policy analysis.

The minutes of this meeting (CFR, January 8, 1968)14 confirm that the CFR had by then become more than a policy forum: it was operating as a de facto node of long-range covert governance, playing the same structural role in the U.S. that the RIIA fulfilled in Britain. Rather than merely analysing global events, the CFR actively participated in shaping tomorrow, coordinating with intelligence elites such as Allen Dulles and Robert Amory Jr. As Marchetti and Marks detail in The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence, Bissell felt free to speak openly because the CFR audience was drawn from a trusted network of financiers, academics, and media figures — a cultivated constituency. That the meeting’s topic was considered ‘especially sensitive’ further underscores the CFR’s role as a strategic interface: where covert planning was not only discussed, but aligned, endorsed, and prepared for operationalisation through bodies like the Forty Committee, COMIREX, and global surveillance infrastructures.

The Council on Foreign Relations book titled Continuing the Inquiry15 even admits as much is true, with additional detail relating to its early days:

The scholars of the Inquiry, returning from Paris, saw an opportunity. The American Institute of International Affairs envisioned at the Hotel Majestic could provide diplomatic experience, expertise, and high-level contacts but no funds. The men of law and banking, by contrast, could tap untold resources of finance but sorely needed an injection of intellectual substance, dynamism, and contacts—whether to promote business expansion, world peace, or, indeed, both. This was the synergy that produced the modern Council and promoted its unique utility for decades to come: academic and government expertise meeting practical business interests, and, in the process, helping conceptual thinkers to test whether they stood on “rock or quicksand.”

What’s truly remarkable about this book is that is says the quiet part out loud:

Lionel Curtis, a leading light in London’s Chatham House, had written that “right public opinion was mainly produced by a small number of people in real contact with the facts, who had thought out the issues involved.”

In ways, it’s almost staggering to be confronted with this level of honesty. Would they admit as much unless they thought of themselves as anything but untouchable?

The Council on Foreign Relations functioned at the core of the public institution-building of the early Cold War, but only behind the scenes. As a forum providing intellectual stimulation and energy, it enabled well-placed members to convey cutting-edge thinking to the public—but without portraying the Council as the font from which the ideas rose.

The book is chock full of admissions. The only question is where the CFR fits in.

Well, an obvious point of entry is through the CIA. Not merely because of the memberships of Allan Dulles16, Richard Bissell and Robert Amory, Jr1718; three of the four members of the top brass ousted by JFK post-Bay of Pigs. No, because the CFR in fact recruited19 members20 from21 within22 the CIA itself, who even nominated agents for memberships.

In fact, if you pay particular attention, you might even find a memo speaking of Allen Dulles — the very top boss of the CIA — being nominated for a CFR Director role23.

Allen Dulles was even aware of an early version of the subversive ‘Freedom Academy’, and pointed towards the likes of the Council on Foreign Relations as vanguards of democracy24 — while we also find that Kissinger book was forwarded to Dulles25, and that… Kennedy was not a member, though he had written articles for their flagship magazine, Foreign Policy, before establishing26:

THE LAST FOUR American secretaries of state have been council members—Dean Rusk, Christian Herter, the late John Foster Dulles, and Dean Acheson.

Taking it the other way around, no fewer than five of the council's present directors also have top posts in Washington, and a sixth is slated for one.

In the infamous words of Inspector Cluseau, It's so obvious the Council on Foreign Relations that it could not possibly be the CFR27.

But instead, let’s have a look at what would have been Amory’s gig: COMIREX — the Committee on Imagery Requirements and Exploitation — folded under the Deputy Director for Intelligence (DD/I), from where it coordinated satellite intelligence28 from the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) and the National Photographic Interpretation Center2930 (NPIC), providing continuous analysis of expressly the sort outlined as highly valuable by The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence.

Quite the marvellous character to have on board the CFR.

And the Forty Committee — the covert governance node approving political subversion, NGO collaboration, and paramilitary intervention — was headed by fellow CFR member, Henry Kissinger. But they were not functioning alone, with the 1975 Commission on the Organization of the Government for the Conduct of Foreign Policy31, backed by Nelson Rockefeller, openly proposing that the Forty Committee be institutionalised within the State Department and tightly coupled with civil society organisations. The report endorses the fusion of covert operations with public-private coordination under democratic pretext — making clear that civil society actors, universities, and foundations were fellow stakeholders of the future agenda.

The prior Rockefeller-led Commission on Critical Choices for Americans32 (1973–74) had ideologically prepared for this fusion, framing population trends, environmental governance, and ‘global interdependence’ as challenges calling for predictive, systems-based management. And this convergence — COMIREX data flowing through the DD/I to private think tanks, operational plans refined in CFR working groups, and missions executed with ‘non-state’ cultural, media, or academic involvement — created a seamless covert-state apparatus. The 1975 Rockefeller Report33 makes this explicit: universities and NGOs were ideological comrades in terms of foreign policy.

And because key actors — Amory, Schlesinger, Bissell, and others — were deeply embedded in both intelligence and CFR structures, the distinction between planner, administrator and operator all but evaporated. The CFR, leveraging its access to intelligence product and policy actors, emerged not just as an advisory body, but as the institutional interface where surveillance, covert action, and global planning were synthesized.

What thus emerged was a new model of governance: long-range strategic objectives defined through elite networks; intelligence routed through COMIREX and the DD/I; policy rubberstamped by the Kissinger-led Forty Committee; and operational execution by the CIA, partially outsourced to a network of NGOs and corporations — with foundation funding. This system — while presented as democratic — was in practice a tightly integrated, technocratic apparatus, which through its operating front of the CIA operated globally, and post-democratically.

This structural fusion found its ideological and administrative consolidation through Nelson Rockefeller, who regularly functioned as a coordinating architect — positioned at the nexus of civil society, state planning, and covert strategy. And documents from the CIA archives reveal Rockefeller’s coordination with figures like Colby and Kissinger3435 to mitigate the public36 fallout37 from38 the Church and Pike commissions. Rather than sever ties with civil society fronts, Rockefeller legitimised these as instruments of strategic operations, while his various roles — from steward of philanthropic capital to Vice President — allowed him to synchronise the levers of soft power with the architecture of strategic planning taking place within the Council on Foreign Relations.

Thus, the post-democratic architecture was not merely born of operational necessity or ideological alignment. It was engineered — through commissions, reforms, and consensus manufacturing — to displace popular sovereignty with managerial control. The CFR and Rockefeller spheres did not oppose intelligence overreach; they engineered, approved and redirected it, embedding surveillance and planning into the very fabric of international civil society.

In 1976, George HW Bush rose to the top position of the CIA39, before becoming Vice President under Ronald Reagan40 — who was nearly assassinated shortly into his presidency41. Though the attempt ultimately failed, it perhaps tempered Reagan’s policies just a touch.

Of course, this was the same George HW Bush who, as US Representative to the United Nations in 1973, penned the foreword to Phyllis Tilson Piotrow’s World Population Crisis42.

Bush then went on to become President of the United States in 198843, serving only a single term before Clinton and Gore were elected. But though his time in office lasted just four years, he was the first president to publicly speak of the New World Order44, while the Clinton-Gore administration went full throttle in implementing the agenda. Not only did they align with Blair’s vision of a ‘Third Way’, but they also carried out the early work leading to the first long-form version of the Ecosystem Approach under a Gore-established task force. Clinton then announced sweeping global infectious disease surveillance under the DoD-GEIS label in 1996, and by 1998 was speaking of ‘information terrorism’45 — an initiative echoed by Russia46, which eventually evolved through claims of misinformation and led to ‘ethical’ censorship — particularly through UNESCO and the Broadband Commission, culminating with the Global Digital Compact in 2021.

Bush’s son, ‘Dubya’, came to power in the much-contested 2000 election versus Gore, where the fate of the presidency was ultimately decided by the infamous hanging chads47 — with the decision eventually called in favour of the Republican. His presidency saw Anthrax letters48 leading to a surge in biosecurity initiatives and a national health security agenda, eventually channelled into pandemic planning — which, incidentally, began in 1976 at a conference in Rougemont at the exact same time as the Fort Dix Swine Flu episode allegedly kicked off. But Dubya also presided over 9/11 itself which led to global surveillance legitimised via the Patriot Act, and the collapse of Enron, which ushered in Business Ethics, ultimately leading to current, progressive deployment of EGS and CSR.

As for Bush Senior, he was reportedly linked to the CIA within a week of Kennedy’s assassination49, whose administration included three Rockefeller men in its inner circle5051, including even the Vice President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, serving as Under Secretary of the Treasury for Monetary Affairs. Yet, Kennedy52, post-Bay of Pigs, called for an investigation of the CIA53 — and the rest is history.

Finally, as for Rockefeller himself, he was not shy of associating with the world’s most notorious dictators. While David Rockefeller travelled to Moscow in 1964, John D. Rockefeller III went to meet the Romanian dictator Ceaușescu in 197554.

Incidentally, Robert Amory Jr. briefed President Kennedy on Israel’s nuclear program in early 196355, following CIA surveillance of the Dimona site5657, where construction had begun in 1959. While Amory played a role in early intelligence assessments, his successor, Ray Cline, would later oversee related developments through COMIREX. This topic, however, warrants separate treatment.

By the early 1970s, the structural consolidation of covert power had already been exposed by Colonel L. Fletcher Prouty, whose 1973 book The Secret Team58 offered a rare, first-hand account of how the U.S. intelligence apparatus had quietly displaced the mechanisms of democratic control. Prouty, having served as Chief of Special Operations for the Joint Chiefs of Staff, revealed how the CIA — far from being merely a collector of intelligence — had become the logistical and operational nerve center for a global network of influence. He argued that a hidden managerial elite, operating through a fusion of military, corporate, and intelligence assets, had effectively assumed the reins of governance.

What Prouty described was not a conspiracy in the theatrical sense, but a structural shift — an inversion of authority wherein policy was no longer generated by constitutional deliberation. Legal frameworks gave way to operational prerogatives; public debate was supplanted by private consensus. The intelligence community no longer served the state — it was the state, or more precisely, the vector through which an unaccountable class could act with impunity and without constraint. As Prouty put it, covert operations had become ‘the principal vehicle of foreign policy’, with public diplomacy reduced to façade.

The assassination of John F. Kennedy, in his account, marked not simply the end of a presidency, but the unshackling of a suppressed agenda. What followed was not chaos, but coordination: a silent alignment of institutional actors — military, intelligence, and civil society — whose interests converged around continuity, control, and the projection of power beyond borders. The apparatus that had been constrained under Kennedy was swiftly normalised under Johnson and formalised through instruments like the Forty Committee, the expansion of PPBS, and the rise of predictive governance.

But where Prouty’s diagnosis ended in the early 1970s, the structure he described continued to evolve — away from clandestine sabotage and toward institutionalised management. What began as covert operations justified by Cold War urgency matured into long-range planning systems governed by global surveillance, digital twins, metrics, and algorithmically predicted forecasts. And the same logic that once mobilised coups and proxy wars now shapes environmental indicators, ESG compliance, and stakeholder governance.

But even as early as 1964, The Invisible Government59 by David Wise and Thomas B. Ross outlined the infrastructure that was being quietly normalised after JFK’s death. The book describes how foreign policy decisions, covert operations, and even civil society engagement increasingly migrated into a shadow architecture — one that included the CIA, the NSC’s Special Group (54/12), private foundations, and unaccountable committees. While the authors never considered this a deliberate replacement for democratic governance, their account makes clear that by the early 1960s, a fully functional parallel authority structure already existed — operating outside congressional oversight and public visibility, but perfectly suited to expand the systems Kennedy began to challenge.

This shadow framework aligned seamlessly with the post-1963 trajectory detailed above: the expansion of PPBS under LBJ, the institutionalisation of COMIREX, the creation of the Forty Committee, and the integration of civil society into strategic planning — The Invisible Government serves as confirmation that the architecture for cybernetic governance had already taken form before Dallas. But for it to flourish, it required the removal of the one man who increasingly opposed its logic. In that light, JFK’s assassination did not merely mark a political transition; it signified the unlocking of an engineered potential, designed to convert democratic legitimacy into managerial consensus through satellite surveillance processed into indicators.

Finally, Zbigniew Brzezinski’s book, Between Two Ages (1970), offers the most explicit discussion of what had, by the late 1960s, already begun to operationally materialise. While Schlesinger, Amory, and Bissell helped build the machinery, Brzezinski provided its ideological manual, calling for a transition from industrial democracy to a ‘technetronic society’, governed not through the traditional political pipeline, but by systems analysis, forecasting, and elite-managed consensus, arguing that technological integration would soon render traditional nation-states obsolete, replaced by a new structure built on global interdependence, soft coordination, and ‘anticipatory’ governance.

Brzezinski’s further proposed institutional reforms that would blur distinctions between public and private, eliminate the legal-political boundaries of national sovereignty, and integrate science, media, education, and civil society into a single feedback system — all in service of managing global priorities deemed too ‘complex’ for democratic participation. He framed this as rational humanism, but in practice it was cybernetic managerialism cloaked in morality. And far from remaining speculative, these ideas took institutional form just three years later, when Brzezinski co-founded the Trilateral Commission alongside David Rockefeller in 1973.

The Trilateral Commission embodied every principle outlined by Brzezinski. It created a supranational forum linking North America, Western Europe, and Japan — the very alliance he described as necessary for transitioning toward global management. But its purpose was not just dialogue; it was policy harmonisation through consensus manufacturing, with civil society actors, academics, and media elites included explicitly to shape public discourse. The Commission’s founding papers reflected Brzezinski’s earlier blueprint: planetary humanism, economic interdependence, and the construction of institutional mechanisms to engineer the ‘common good’ outside the bounds of electoral legitimacy — which in 2020 were eventually turned into calls for ‘inclusive capitalism’.

In this context, the events following JFK’s assassination — the expansion of PPBS, the rise of COMIREX, the Forty Committee, and the Rockefeller-coordinated civil society capture — can be seen as the progressive construction of the managerial system Brzezinski would later state had already come into being. His book merely described the trajectory inaugurated in Dallas.

In other words — it’s hard to move in any direction from here without cleanly fitting into a story already told. All the pieces fit together perfectly. But, yet, this is still just a touch off clinched. So let’s return to the one substantial inflection point in the transition of power from JFK to LBJ — the one which might well explain why JFK had to go. And to make the case, let’s return to 1961 and McNamara’s implementation of PPBS within the Department of Defense.

Because this, after all, went on to become a global enterprise.

To be concluded.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The price of freedom is eternal vigilance. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.