The Trilateral Commission

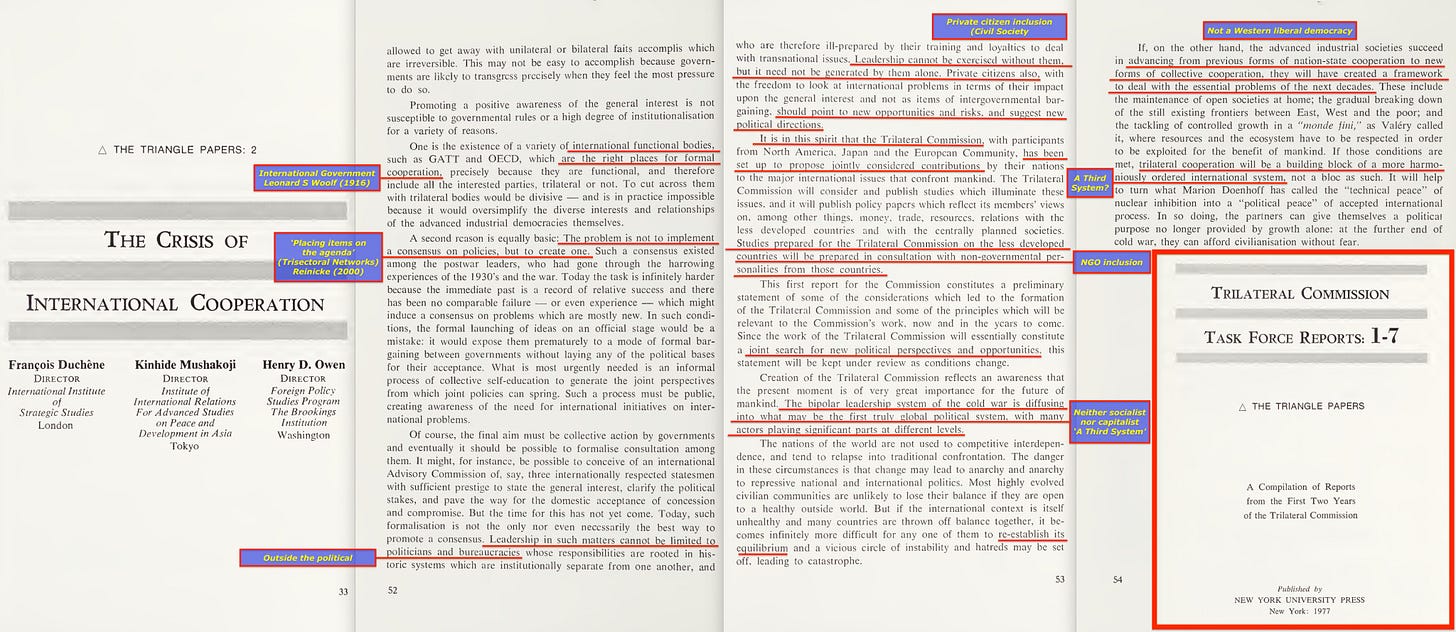

In 1973, the Trilateral Commission was launched as a forum which, in effect, laid the groundwork for Wolfgang Reinicke’s later Trisectoral Networks: Public–Private–CSO partnerships for 'the common good', where the CSO (NGO) defines the 'common good'—and legitimate democracy has little, if any, say.

But—true to form—it had to be rolled out by stealth. And that’s where the New International Economic Order enters the stage, with IFDA’s Third System following only a few years later.

We’ve returned to this topic time and again. It’s always the same model. Always.

Public labour — private capital — with a third party defining the ‘common good’.

The model originates with Eduard Bernstein (1899), who expanded upon Julius Wolf’s earlier framework from 1892. Bernstein essentially introduced the idea of the common good as a mediating force between state and capital—an addition that transformed Wolf’s original public-private partnership into a vehicle for managerial governance. Wolf’s model itself was grounded in a gold clearance mechanism that would later be absorbed by the Bank for International Settlements in 1930.

Leonard S. Woolf, drawing on both Bernstein and Wolf, applied this logic to international affairs in his Fabian Society report International Government (1916). There, he proposed that supranational organisations—enabled by what we now call neoliberalism—would gradually absorb national sovereignty. This transfer of power, he argued, would emerge naturally from open borders and tariff-free trade, as these mechanisms slowly force harmonisation of cross-border policy.

In 1921, Lenin implemented the same model domestically, placing the Communist Party in the role of the third actor—the body defining the common good. However, according to Anatoliy Golitsyn, Khrushchev later revived and adapted this model for long-term global strategy in the late 1950s. And when Mikhail Gorbachev rose to power in 1985, his perestroika followed that same script. Golitsyn’s Perestroika Deception suggested this was the final stage of Khrushchev’s long-game, and that claim gains credibility when we consider Gorbachev’s pivotal 1987 speech—one that subtly signalled the shift from the Cold War threat to a new global narrative: environmentalism as the unifying cause, and the alleged collapse of the Soviet threat.

Tony Blair outlined the same system in 1991, though he stopped short of specifying who should define the ‘common good’. That omission was addressed later—in 1998—with The Third Way, a pamphlet published by the Fabian Society, echoing Leonard Woolf’s earlier model. But the groundwork had already been laid in Blair’s 1994 pamphlet Socialism (also Fabian-published), which directly revived Eduard Bernstein’s 1899 principles. Together, these writings paved a clear path toward what would soon be branded as Moral / Inclusive Capitalism1—a framework that emerged just ahead of the launch of the Sustainable Development Goals.

The United Nations, too, adopted this same model—placing Civil Society Organisations in the role of agenda-setters. Most recently, this was formalised through Wolfgang Reinicke’s Trisectoral Networks (2000), an initiative incubated by the World Commission on Dams (1997–2000). But the lineage stretches further back—through Our Global Neighbourhood (1995), and before that, the 1992 Rio Earth Summit, where the widely misunderstood soft law document Agenda 21 was born. What few recognised at the time was that the entire document quietly operationalised this very same public–private–CSO structure at the heart of global governance.

This marked a subtle but critical evolution of the Brundtland Commission’s 1987 report, Our Common Future—a document that reframed the world as a single interdependent system, ready to be managed through systems theory. This opened the door to conceptual frameworks like Spaceship Earth, One Health, Ecosystem Health, and The Total Human Ecosystem. It also laid the groundwork for the Circular Economy—a model that, by design, requires continuous global surveillance as raw data input for its emerging Digital Twin infrastructure, grounded in General Systems Theory.

But the UN’s embrace of this model goes back even further. In the late 1970s, the Maurice Strong–backed IFDA formalised it as the Third System—with Civil Society Organisations (NGOs) occupying the role of the third party. This system emerged shortly after the New International Economic Order and was quietly implemented across G77 nations—the so-called Third World—under the condition of continued development aid. Reject the public–private–CSO model, and the aid would be cut. For many struggling nations, this wasn’t a choice—it was coercion in soft law form.

The Third System was a strategic triumph. It realised, in practice, the full model Leonard S. Woolf proposed in 1916—this time through the dual perspective of environment and development. But to implement a such system on a global scale, the proper institutional machinery had to exist. That’s where the United Nations comes in—a body which, in more ways than one, was nothing short of a continuation of the League of Nations.

The League, co-founded by Alfred Zimmern—who also co-founded not only the Royal Institute of International Affairs (Chatham House) but also helped design the administrative skeleton of future UNESCO through the IIIC/ICIC split—directly borrowed from Woolf’s International Government. The blueprint was clear: siphon authority away from sovereign states and concentrate it in specialised international organisations, each focused on a particular sphere of the so-called common good.

One key sphere targeted early on was science. Alongside the founding of the League of Nations in 1919 came the establishment of the International Labour Office—to represent workers—and the International Research Council (IRC), which was tasked with steering the League’s scientific agenda.

But by 1931, the IRC was dissolved and replaced by the International Council for Scientific Unions (ICSU)—an entity entirely removed from government oversight. Unsurprisingly, foundation funding followed close behind.

Under ICSU’s expanding umbrella, a network of subcommittees emerged, including SCOPE (the Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment). SCOPE played a dual role: it not only produced the technical reports that would underpin the emerging global surveillance system (GEMS), but also helped manufacture the so-called scientific consensus throughout the 1980s. This campaign crescendoed in ever-more extreme claims of catastrophic global warming—despite the absence of credible, settled science at the time.

This narrative was formally launched at the invite-only 1979 World Climate Conference, organised by foundation-funded ICSU, where an implicit carbon consensus was introduced—well in advance of any legit evidence. From the outset, the science was shaped to serve the emerging managerial system.

In many ways, the United Nations simply carried forward the legacy of the League of Nations—using the same organisational framework first articulated by Leonard S. Woolf in International Government (1916). This continuity was especially evident in science governance. Shortly after UNESCO’s founding, it was effectively fused with the ICSU, creating a powerful nexus for controlling the direction of international science.

From this platform, the "best available scientific consensus" was not discovered—it was engineered. Conveniently, Julian Huxley—UNESCO’s first Director-General—split off to co-found the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in 1948. The IUCN’s mission was clear from the outset: to manage, conserve, and ultimately govern the planet’s natural resources. In modern terms: Planetary Stewardship.

That vision was formally launched in 1980 with the publication of the World Conservation Strategy, followed by its more public-friendly update, Caring for the Earth (1991)—released just months before the Rio Earth Summit. Crucially, this latter document introduced the concept of a global ethic for nature conservation, framing environmental governance in moral terms.

Over time, the IUCN grew into the dominant actor in the environmental NGO landscape, quietly shaping international policy behind the scenes. What began as a call to conserve 17% of the planet’s ecosystems soon became 30%. And most recently, the IUCN adopted the WILD Foundation’s 2009 proposal: Nature Needs Half. Half the Earth, reserved—allegedly—for nature.

Except, of course, these were promptly monetised for any type of ‘ecosystem service’ in existence, starting with carbon emission credits.

This, in essence, is the skeleton of the plan. But one could go further—into the more overtly subversive and manipulative layers. The call for planetary stewardship is gradually transmuted into a global ethic, which is then embedded into education, culture, religion, and law. The ultimate goal? To mould you into a compliant, well-behaved moral agent—conditioned to obey, not to question.

This process mirrors, almost perfectly, the ideological architecture of Alexander Bogdanov. His concept of empiriomonism sought to unify knowledge, belief, and science under a single worldview. His Proletkult movement aimed to shape culture in service of political ends. And his organisational framework—tektology—was the forerunner to General Systems Theory, now foundational to modern Adaptive Management. In other words, this is not just environmental policy. It is full-spectrum cultural engineering under a banner of alleged, planetary care.

What absolutely bears repeating is this: at present, the United Nations operates through a global structure increasingly dominated by unaccountable NGOs holding General Consultative Status. These entities, unelected and opaque, are quietly steering global policy.

And in more recent developments, this model is entering new territory. In the UK, NGOs are now being formally included in roundtable discussions with the Treasury and the Bank of England. The initiative is called the EPCC—and its stated aim is, in effect, to transfer influence away from publicly elected officials and into the hands of central bankers and civil society actors operating entirely outside of democratic oversight.

This is not democratic in any meaningful sense of the word. And unsurprisingly, not a single major media outlet has touched the story.

We are witnessing a slow-motion global takeover—so gradual, so procedural, and so cloaked in institutional legitimacy that it escapes notice. But make no mistake: the ultimate objective is the transfer of political authority away from nation-states and into the hands of unaccountable NGOs—and above all, central banks.

In 1970, Zbigniew Brzezinski published ‘Between Two Ages‘2, where he argued that humanity was entering a new era—an integral age—in which traditional notions of national interest and sovereignty would steadily erode under the weight of a global technological revolution.

This ‘new humanist society’, as he frames it, demands precisely the kind of neoliberal internationalism Leonard S. Woolf called for in 1916—enabled by free trade and the abolition of tariffs. Yet, despite the infrastructure for integration, Brzezinski laments, the unity of mankind remains elusive.

Instead, he observes the rise of special interest and pressure groups—first in American metropolitan areas, and increasingly in a global context. These patterns echo Woolf’s vision: a world where sovereign power is slowly but deliberately absorbed by international organisations, transcending national boundaries through technocratic coordination.

At the core of this transformation is what Brzezinski calls the technetronic age—a system where advanced modelling, automation, and cybernetics are employed to predict social behaviour and manage human systems. Both East and West experiment in this space, using global modelling as a foundation for shaping policy and reengineering society based on algorithmically derived foresight.

This emerging order demands a new form of universal education, one suited not to cultivating citizens, but to preparing functionaries for a world where human labour is increasingly obsolete. And in terms of governance, he writes:

… plutocratic pre-eminence is challenged by the political leadership, which is itself increasingly permeated by individuals possessing special skills and intellectual talents.

In other words, technocracy—the fusion of governance with technocratic expertise—is gradually embedding itself into the American system. Universities, he implies, are becoming de facto think tanks—hypothetically outsourced policy engines for elite planning networks like the RIIA and CFR.

Yet this raises a significant issue: political participation. Brzezinski acknowledges the growing alienation of the public:

The issue of political participation is a crucial one. In the technetronic age the question is increasingly one of ensuring real participation in decisions that seem too complex and too far removed from the average citizen. Political alienation becomes a problem.

And the proposed ‘solution’? The inclusion of Civil Society stakeholders in policy-making processes that are, in reality, anything but democratic. The very decisions that matter most are redefined as too complex for public input—thus requiring the mediation of ‘experts’ and NGOs.

This rationale is nearly identical to the principle of Subsidiarity—which claims to decentralise power, but in practice does the opposite. It centralises all meaningful decision-making at the highest level, while leaving local councils to debate the colour of parking metres.

And the echoes of CSOs continue, as Brzezinski adds:

In the technetronic society the trend seems to be toward aggregating the individual support of millions of unorganized citizens, who are easily within the reach of magnetic and attractive personalities, and effectively exploiting the latest communication techniques to manipulate emotions and control reason

That description, of course, applies just as much to politicians as it does to activists—though Brzezinski conveniently omits that detail. He quickly and quietly pivots back to the machinery behind it all:

The tendency toward depersonalization economic power is stimulated in the next stage by the appearance of a highly complex interdependence between governmental institutions (including the military), scientific establishments, and industrial organizations

The language here is inching toward the NGO model—though he doesn’t say it outright just yet.

Then comes the clincher:

In the technetronic society the adaptation of science to humane ends and a growing concern with the quality of life become both possible and increasingly a moral imperative for a large number of citizens, especially the young.

In short: we must manufacture support by targeting the young—those most malleable and impressionable. These are to be shaped by 'magnetic and attractive personalities', amplified by the latest communication tech, designed explicitly to 'manipulate emotions and control reason'. All under the noble-sounding banner of a new 'moral imperative'.

And thus the seed is planted: a synthetic ethic, engineered through marketing, masked as morality.

According to Brzezinski, this carefully cultivated moral imperative will gradually give rise to a ‘planetary consciousness’—which, in unmistakably Ken Wilber’esque fashion, unfolds like a cosmic inevitability:

A global human conscience is for the first time beginning to manifest itself. This conscience is a natural extension of the long process of widening man's personal horizons. In the course of time, man's selfidentification expanded from his family to his village, to his tribe, to his region, to his nation; more recently it spread to his continent

In other words: the expansion of identity is being framed as evolution. But what we are really witnessing is the strategic remapping of allegiance—from family, tribe, and nation, to an abstract global 'we'. And this shift isn’t happening organically. It’s being manufactured.

The tools? Education and culture—which, in this context, are less about knowledge and heritage, and more about cultural engineering. Sustainability serves as the perfect vehicle: morally framed, scientifically cloaked, and institutionally enforced.

Brzezinski goes on to outline the rise of transnational elites—though, curiously, he omits any mention of how Woolf’s blueprint helped bring them into being. These elites are drawn from a familiar pool: businessmen, scholars, professionals, and public officials—or, in today’s parlance, stakeholders.

These altruistic, cosmopolitan planners spend their days contemplating global crises—overpopulation, climate, resource management—all in pursuit of what they assure us is the ‘common good’… though notably, they never actually bother asking us what this common good should be.

A polite ‘thank you’ is surely in order. Thank you, dear cosmopolitan elite, for solving the world’s problems on our behalf—whether we like it or not.

The scientific revolution, Brzezinski suggests, will increasingly allow these elites to harness the power of global modelling—not to empower humanity, but to ‘solve’ problems related to common goods you likely didn’t even know existed. After all, these issues were never meaningfully debated—only introduced through a few emotionally charged catchphrases, endlessly repeated until they became orthodoxy.

And what are these ‘common goods’? The usual suspects: air and water pollution—problems which, we're told, were to be solved by monetising them through UNCTAD in 1992 and 1994. All, of course, for our common good.

So once again—thank you, altruistic cosmopolitan elites.

I’m sure the next phase—monetising every ecosystem service on Earth—will work out just fine. Water, air, soil, sunlight—everything we depend on to live—now slated for financialisation, all in the noble name of protecting the planet.

The monetisation of ecosystem services hadn’t yet been formally detailed in 1970, but ecology was already a hot topic. The Odum brothers were pioneering Systems Ecology3, framing ecosystems as input–output systems—nutrient flows, energy cycles, and feedback loops. And naturally, if you want to manage a system, you must monitor it. So, if our altruistic cosmopolitan elite were to truly protect Spaceship Earth, it would logically require global surveillance—continuous, comprehensive, and quietly imposed.

And wouldn’t you know it—SCOPE set out to tackle precisely this problem in 1971. Just a coincidence, of course. And by 1974, the Global Environment Monitoring System (GEMS) was underway—tracking not only environmental factors but extending into public health surveillance.

Because, after all, man is part of the ecosystem too. Therefore, if one is to protect the environment, one must also monitor and manage human behaviour—individually, collectively, biologically.

This logic—balancing humanity with nature—was first formally introduced at the 1968 UNESCO Biosphere Conference. There, René Dubos of Rockefeller University (purely coincidentally, I’m sure) drafted Recommendation 3, warning of the risks posed by zoonotic diseases emerging from increased contact between humans and animals.

And as it happens, 1968 was also the year of the Hong Kong flu, a zoonotic influenza said to have spread globally. A terrifying illness, we are now told—though at the time, it barely registered outside the usual range in contemporaneous MMWR reports.

A terrifying illness—in retrospect, following many helpful revisions over time.

Brzezinski further adds:

The concern with ideology is yielding to a preoccupation with ecology. Its beginnings can be seen in the unprecedented' public preoccupation with matters such as air and water pollution, famine, overpopulation, radiation, and the control of disease, drugs, and weather, as well as in the increasingly nonnationalistic approaches to the exploration of space or of the ocean bed. There is already widespread consensus that functional planning is desirable and that it is the only way to cope with the various ecological threats. Furthermore, given the continuing advances in computers and communications, there is reason to expect that modern technology will make such planning more feasible; in addition, multispectral analysis from earth satellites (a byproduct of the space race) holds out the promise of more effective planning in regard to earth resources.

So, not only was intrusive public health surveillance quietly normalised—without so much as a whisper of meaningful debate—but now, we’re told, our altruistic cosmopolitan elites are looking to the heavens to manage us from above.

Satellite surveillance, naturally, is presented as the next logical step in ‘functional planning’—to save us not from war or ideological extremism, but from the true threat: ourselves.

Because when ideology fades, ecology steps in to take its place—not as science, but as system. One that requires monitoring, modelling, and management… from orbit!

Next, Brzezinski brings Teilhard de Chardin into the frame, outlining the gradual emergence of a collective human consciousness—a process, he argues, that must be cultivated through cultural engineering. This engineered consciousness is intended to lead to social activism, driven not by reasoned discourse, but by a kind of moral reflex—activism for the 'collective good'.

In theory, it sounds noble. In practice, it looks more like this: businesses torched, innocent people ruined, and hired mobs throwing bricks at police with total impunity. The result? A new kind of 'democracy'—activism democracy—bankrolled by ‘philanthropic’ foundations, cloaked in moral language, and weaponised under the banner of the 'common good'.

Next comes Brzezinski’s highly selective retelling of the nation-state’s origins and function, followed by an equally lopsided treatment of religion. Then, without much warning, he drops to his knees in admiration of Marxism—though he’s quick to clarify that it was merely implemented incorrectly. The intent, he assures us, was noble: striving for the 'common good'.

Never mind that Marx never actually explained how the so-called dictatorship of the proletariat would magically wither away. Lenin, of course, resolved this little oversight by installing a Vanguard police state—temporary permanence.

Bogdanov, however, offered a more elegant solution: the ideological saturation of everything—education, art, science, culture. This was his Proletkult, his plan for embedding doctrine into the very fabric of life. A remarkably similar approach to what Brzezinski quietly recommends—though I’m sure that’s just a coincidence.

But communism isn’t just communism—not in practice, anyway. There are multiple variations spun from its core principles. The Soviet Union pursued one path, China another. But it’s Yugoslavia that Brzezinski finds particularly interesting, citing it as a model experimenting with reforms not unlike Lenin’s New Economic Policy.

Yugoslavia will continue to evolve toward a more pluralist pattern and to cultivate closer contacts with the West—no doubt including something like associate status in the European Common Market. It may even begin to experiment with multiparty elections, and it is likely to be less and less doctrinaire about the classical issue of state versus private ownership. Yugoslav theoreticians have already argued publicly that a multiparty system is a necessary mechanism for avoiding the political degeneration inherent in the communist party power monopoly

Yugoslavia is a case that hasn’t yet received attention on this Substack—but it should. Its reforms mirrored Lenin’s NEP, leaned toward Woolf’s internationalism, and echoed Bernstein’s evolutionary socialism.

Of the countries where communism came to power without being imposed by foreign intervention (the Soviet Union, China, Cuba, Yugoslavia, Albania, Vietnam), only Yugoslavia has so far succeeded in achieving sustained economic growth, social modernization, and political stability without employing massive terror or experiencing violent power conflicts; even Yugoslavia, however, required extensive outside financial aid

That’s not quite the full truth but that last bit deserves emphasis. Extensive outside aid was the price of Yugoslavia’s moderate image. Its form of communism—while less brutal than Stalin’s—was still communism. Private enterprise existed at the regime’s discretion and could be shut down at a moment’s notice, much like under Lenin’s NEP.

Part 4 of Between Two Ages is titled The American Transition. Transition to what, exactly? That’s the question—though by now, the answer is becoming obvious. After spending several chapters subtly implying that real communism has never been tried (Yugoslavia is making remarkable progress, until it fails, at which point he will promptly disown the position), Brzezinski now shifts gears to describe the very same endgame—this time from the American perspective.

He already has the destination in mind—it’s just a matter of shepherding the reader there, using carefully coded Aesopian language. After all, this book wasn’t really written for you.

In this new technetronic future, science is framed as the instrument through which society’s ills will be corrected. What America needs, Brzezinski argues, is a fresh set of integrative values—something to unite the country as it transitions from an industrial to a technetronic society.

But let’s fast-forward to Part 5, where the same framework is extended globally:

The success of America in building a healthy democratic society would hold promise for a world still dominated by ideological and racial conflicts, by economic and social injustice

Translation: the tools of technocratic governance, dressed up as scientific neutrality, will now be used to address the world’s remaining unsolved problems—like racial inequality and social injustice. And how best to solve these?

Why, by institutionalising explicit discrimination, of course—particularly against white men. Just don’t call it that. Wrap it in euphemisms like equity, corrective justice, or inclusive governance, and you can reframe prejudice as progress4.

But science—specifically global modelling—isn’t just a neutral tool. It’s to be used deliberately, Brzezinski tells us, as a mechanism for planning the future. And in that context, mob justice and activism democracy—fostered by the New (Violent) Left—can be strategically exploited. Over time, these radical currents aren’t just disruptive; they’re institutionalised. The revolution becomes internal. Policy is no longer dictated from outside the system—it’s smuggled in through the judiciary, through academia, through media. Cue the rise of socialist activist judges, graciously installed by Saint Obama.

All of this, naturally, requires a comprehensive regime of cultural engineering—though, of course, they can’t be too open about it. As Brzezinski puts it:

… two broad areas of needed and—it is to be hoped—developing change involve the institutional and the cultural aspects of American society. The former largely, though not exclusively, pertains to the political sphere, the latter to the educational domain, particularly as it concerns the content and the shaping of national values

Fast-forward a few decades, and what do we have? An education system that rewrite historys, teaches children to despise their parents, their culture, and their heritage. The road to Socialist Utopia is paved through the classroom.

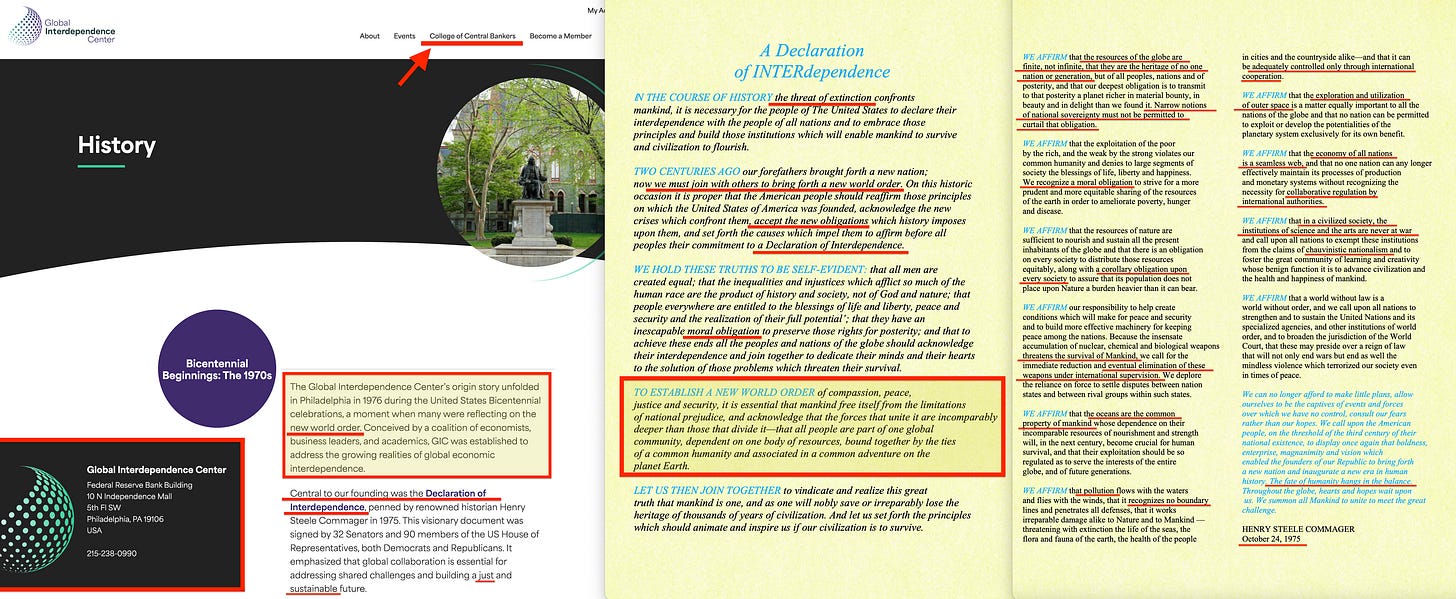

Next comes Brzezinski’s section on 'participatory pluralism'—a gentle-sounding phrase that conceals the redefinition of democracy itself. And here, by pure coincidence I’m sure, we find the 1975 ‘Declaration of Interdependence’, drafted by Henry Steele Commager. It not only openly calls for a New World Order, but it’s also proudly featured in the ‘History’ section of the Global Interdependence Center—hosted, appropriately enough, by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, complete with its own College of Central Bankers.

In a nod to transparency and accountability, they recently scrubbed the document from their website—though the Wayback Machine still has the receipts.

Commager’s declaration calls for the protection of oceans, space, and the environment, alongside the management of pollution through international cooperation. In other words, it’s a carbon copy of Brzezinski’s global vision—right down to the ecological pretext and the supranational enforcement.

But I’m sure that’s just another coincidence.

Either way, the setting of societal common goods—those domains over which science must be tamed and cultural engineering deployed—cannot happen all at once. It must come incrementally, and certainly not openly, lest the public—undemocratically, of course—reject this technocratic revolution for the common good.

Brzezinski puts it plainly:

Realism, however, forces us to recognize that the necessary political innovation will not come from direct constitutional reform, desirable as that would be. The needed change is more likely to develop incrementally and less overtly. Nonetheless, its eventual scope may be farreaching, especially as the political process gradually assimilates scientifictechnological change.

Yes, really—science is to be fused directly into the political pipeline, bypassing public consent. And to what end? Well, this:

Thus, in the political sphere the increased flow of information and the development of more efficient techniques of coordination may make possible greater devolution of authority and responsibility to the lower levels of government and society. In the past the division of power has traditionally caused problems of inefficiency, poor coordination, and dispersal of authority, but today the new communications and computation techniques make possible both increased authority at the lower levels and almost instant national coordination. § The rapid transferral of information, combined with highly advanced analytical methods, would also make possible broad national planning—in the looser French sense of target definition—not only concentrating on economic goals but more clearly defining ecological and cultural objectives

… advanced modelling and real-time data flows now allow for national planning, focused not just on economics, but on ecological and cultural objectives. And since culture and environment are viewed as interdependent systems, managing the one requires engineering the other.

Hence, Planetary Stewardship—a term that, beneath its eco-friendly veneer, amounts to a mandate for cultural engineering, justified by the fabrication of scientific consensus.

This was already well underway by 1975, with the drafting of the Belgrade Charter5. Despite the fact that no credible science yet existed to support the sweeping claims of impending climate doom, the Charter nonetheless insisted on the need to create a global ethic, and to infuse environmental science—which itself barely existed—into education systems worldwide.

The problem had not yet been proven. The data was not yet conclusive. Even Bert Bolin, one of the key architects of the early climate narrative, admitted they didn’t know if temperatures would rise or fall. But no matter. The solution was already in place—science repurposed as ideology, and education weaponised as the delivery mechanism.

What’s particularly revealing is that this target-based governance model—framed as planning for the ‘common good’—was explicitly proposed for policy implementation by Tony Blair in 1998, via the Fabian Society’s publication The Third Way linked above. That same pamphlet also introduced the principle of ‘Subsidiarity’—a term which, despite sounding decentralising, actually does the opposite: it centralises power to the highest level deemed convenient. Precisely what Brzezinski implies throughout, without ever saying it outright.

And then, the next 'solution' in the technocratic playbook arrives—just waiting for the framing of a problem:

Technological developments make it certain that modern society will require more and more planning. Deliberate management of the American future will become widespread, with the planner eventually displacing the lawyer as the key social legislator and manipulator. This will put a greater emphasis on defining goals and, by the same token, on a more selfconscious preoccupation with social ends. How to combine social planning with personal freedom is already emerging as the key dilemma of technetronic America, replacing the industrial age's preoccupation with balancing social needs against requirements of free enterprise.

In other words: comprehensive planning, guided by scientific models, will replace both markets and law as the core mechanisms of governance. Planners—technocrats—will replace lawyers as the architects of social structure. The system will be guided by target-setting, goal alignment, and value definition—all from above.

In short, it’s a soft reboot of Soviet-style governance, updated for the digital age.

And yes, Brzezinski does suggest this may require curtailing individual liberty—not unlike Tony Blair, who in The Third Way quietly redefined freedom as responsibility.

But don’t take my word for it. Read for yourself:

And just when you thought the solutions-to-nonexistent-problems parade might be over, another one rolls by:

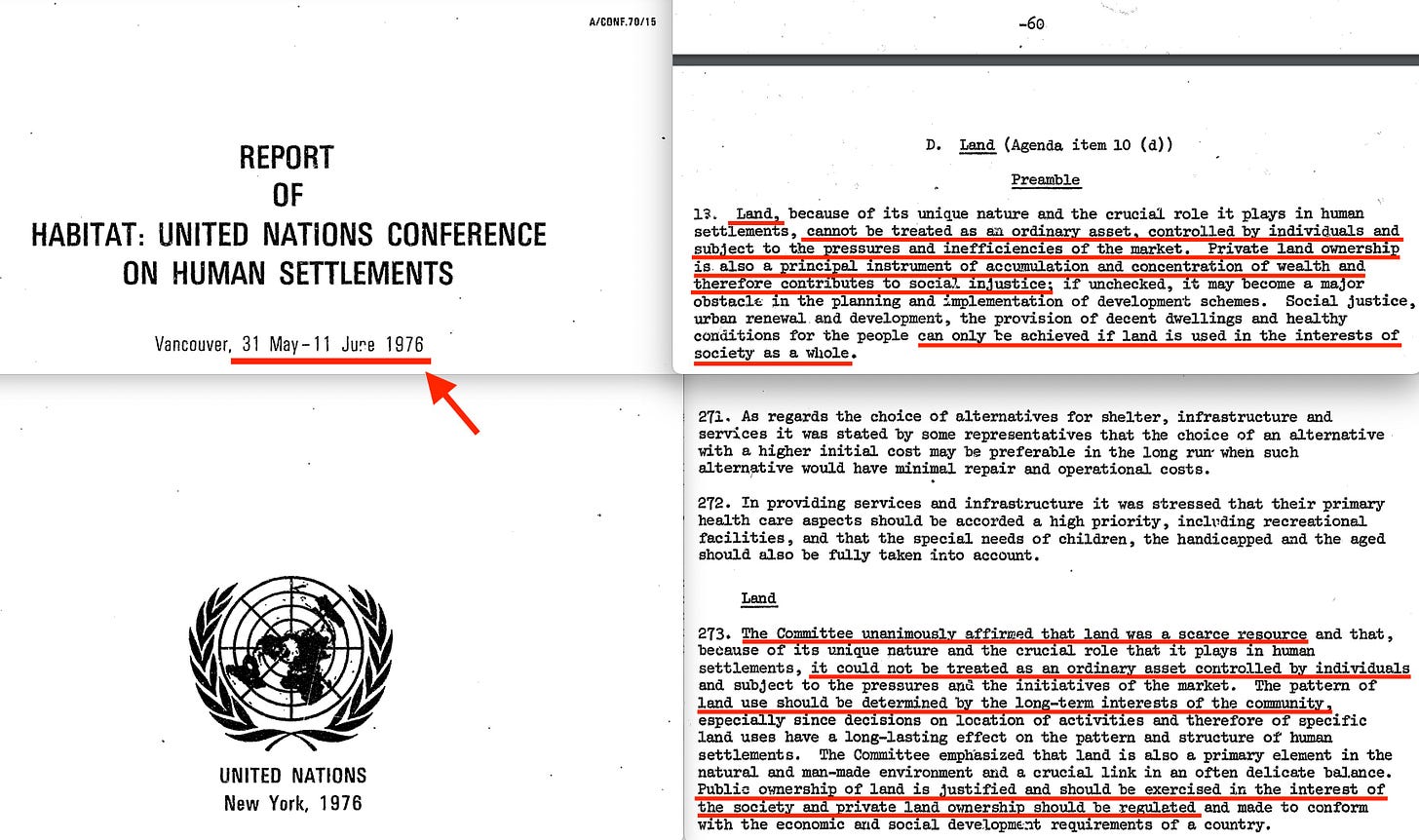

The trend toward more coordination but less centralization would be in keeping with the American tradition of blurring sharp distinctions between public and private institutions… the question of ownership was the decisive social and political issue of a society undergoing modernization. The forms of land ownership…

Now, I could spend fortunes of time outlining how this aligns perfectly with the Ecosystem Approach, or with UN-Habitat’s 1976 recommendations on land tenure reform6, but let’s keep the show moving—after all, it’s probably just another coincidence.

That said, let’s be clear: the Second Malawi Principle (under the Ecosystem Approach) invokes the principle of ‘subsidiarity’—which, in practice, means the local peasant gets to decide whether the flowerbeds in the town square should be tulips or daisies, while all decisions regarding taxation, trade, carbon credits, and surveillance infrastructure are made far above his head, by actors he’ll never meet.

The entire system is a subversive scam, top to bottom. It centralises control into the hands of the unaccountable, wraps it in Aesopian language, and sells it under the banner of 'social justice'. It is, quite literally, Cloaked in Care—a managerial shell game dressed up as compassion.

In the interest of brevity, let’s take Brzezinski’s next passage in full. It’s dense—packed with promises of participation, public-private integration, the taming of science for social ends, and the gradual erasure of boundaries between the public and private spheres:

Our age has been moving toward a new pattern, blurring distinctions between public and private bodies and encouraging more crossparticipation in both by their employees and members. In Europe codetermination not only has involved profitsharing but has increasingly led to participation in policymaking; pressures in the same direction are clearly building up in the United States as well. At the same time, the widening social perspectives of the American business community are likely to increase the involvement of business executives in social problems, thereby merging private and public activity on both the local and the national levels. This might in turn make for more effective social application of the new management techniques, which, unlike bureaucratized governmental procedures, have proved both efficient and responsive to external stimuli.* Such participatory pluralism may prove reasonably effective in subordinating science and technology to social ends.

This is the playbook: erase institutional boundaries, encourage ‘participation’ that bypasses accountability, and subject science to a vaguely defined 'common good'—one that, conveniently, is always defined by the very elites running the system.

But it gets even more revealing in the next section:

Anticipation of the social effects of technological innovation offers a good example of the necessary forms of crossinstitutional cooperation. One of the nation's most urgent needs is the creation of a variety of mechanisms that link national and local governments, academia, and the business community (there the example of NASA may be especially rewarding) in the task of evaluating not only the operational effects of the new technologies but their cultural and psychological effects. A series of national and local councils—not restricted to scientists but made up of various social groups, including the clergy—would be in keeping with both the need and the emerging pattern of social response to change

Take a step back. Then read that again.

Brzezinski is telling you that science and technology are not merely tools to be evaluated on practical grounds—they are cultural weapons. Tools that will reshape not just infrastructure, but psychology, values, beliefs. And in order to do that effectively, he wants cross-institutional mechanisms—councils at every level, populated not only by scientists, but by clergy, civil society actors, and institutional gatekeepers. In short: the full-blown stakeholder governance model.

This is subsidiarity, public-private partnerships, and civil society mediation all rolled into one. And the objective? The formulation of societal goals—not derived through democratic discourse, but defined technocratically, guided by a re-engineered cultural consensus. And the core instrument of this transformation is science—stripped of objectivity, repurposed for social control.

What Brzezinski is describing is science translated through cultural engineering, implemented via social conditioning, to produce a planned, programmable society. And the blueprint? Already being operationalised by environmental NGOs, entirely outside the democratic sphere, under the cover of serving the common good.

If that sounds familiar, it should.

Objective science translated into subjective moral imperative is precisely what Alexander Bogdanov described as Empiriomonism. And the embedding of ideology through education, religion, and art? That’s Proletkult.

But I’m sure that’s just a coincidence.

The former page continues:

The trend toward the progressive breakdown of sharp distinctions between the political and social spheres, between public and private institutions, will not lend itself to easy classification as liberal, conservative, or socialist—all terms derived from a different historical context— but it will be a major step toward the participatory democracy advocated by some of the New Left in the late 1960s. Ironically, this participatory democracy is likely to emerge through a progressive symbiosis of the institutions of society and of government rather than through the remedies the New Left had been advocating: economic expropriation and political revolution, both distinctly anachronistic remedies of the earlier industrial era

Honestly, it’s hard to know where to start. Brzezinski is describing nothing short of the Marxist revolution, only dressed up in corporate-speak and technocratic polish. No gulags, no barricades—just institutional convergence, semantic camouflage, and systemic absorption.

What he’s proposing is, functionally, exactly what Alexander Bogdanov envisioned: not the violent overthrow of capitalism, but its slow subordination to a planned, ideologically infused system of governance through soft coordination, systems theory, and cultural engineering.

He continues:

… in their stead, organized local, regional, urban, professional, and other interests will provide the focus for political action, and shifting national coalitions will form on an ad hoc basis around specific issues of national import… the gradual progress toward a new democracy increasingly based on participatory pluralism in many areas of life. Assuming that short term crises do not deflect the United States from redefining the substance of its democratic tradition, the longrange effect of the present transition and its turmoils will be to deepen and widen the scope of the democratic process in America.

Translation: representative democracy is out, and in its place comes a new model—built on stakeholder groups, sectoral representation, ad hoc coalitions, and consensus-by-committee. What Brzezinski calls ‘participatory pluralism’ is, in reality, a carefully managed simulation of democracy—one that replaces voters with CSOs, NGOs, foundations, industry reps, and academics.

So then—how does this slow-walked, non-violent Marxist revolution unfold?

Brzezinski gives the game away:

The element of deliberate and conscious choice may be even more important here than in the transformation of complex institutional arrangements, because in modern society the educational system and the mass media have become the principal social means for defining the substance of a national culture

Through cultural engineering, executed through education and media, framed as progress and backed by ‘science’. This is Bogdanov’s Scientific Socialism in action—though Brzezinski prefers to dress it up as Rational Humanism. One could just as well call it Paul Carus’s Religion of Science7; moralised scientism in short.

The technological thrust and the economic wealth of the United States now make it possible to give the concept of liberty and equality a broader meaning, going beyond the procedural and external to the personal and inner spheres of man's social existence. By focusing more deliberately on these qualitative aspects of life, America may avoid the depersonalizing dangers inherent in the selfgenerating but philosophically meaningless mechanization of environment and build a social framework for a synthesis of man's external and inner dimensions.

It’s no longer enough to regulate your actions—the system now seeks to redefine your inner life, to align your values and feelings with its engineered conception of ‘liberty’ and ‘equality’. This is full-spectrum cultural programming: values, beliefs, identities, emotional responses—all recalibrated in line with the planned society.

This is Bogdanov’s Proletkult, merged with Julian Huxley’s vision for UNESCO. It is scientifically managed inner life, framed as liberation.

And, as always—it must be internationalist, and very, very cosmopolitan.

But what comes next is truly significant:

There are indications that the 1970s will be dominated by growing awareness that the time has come for a common effort to shape a new framework for international politics, a framework that can serve as an effective channel for joint endeavors. Yet it must be recognized that there will be no real global cooperation until there is far greater consensus on its priorities and purposes… . an emerging global consciousness is forcing the abandonment of preoccupations with national supremacy and accentuating global interdependence.

Global integration through a common purpose — and this will take place in the 1970s, you say? Gee, on May the 23rd, 1972, perchance?

The objective is to synthesise the Soviet Union and the United States. That is to take place through not ideology, but a common purpose, facilitated through scientific cooperation. And that this lived entirely in the shadow of the SALT agreements — explicitly mentioned by Brzezinski — that, too, is a coincidence.

This in turn calls for the creation of a community of nations:

To postulate the need for such a community and to define its creation as the coming decade's major task is not utopianism.Under the pressures of economics, science, and technology, mankind is moving steadily toward largescale cooperation… Movement toward a larger community of the developed nations will necessarily have to be piecemeal… It makes much more sense to attempt to associate existing states through a variety of indirect ties and already developing limitations on national sovereignty.

… though this effort, of course, needs to be instituted slowly and subversively, through indirect ties, so as not to alert the tedious proles. And to that extent:

… the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe on the one hand and Western Europe on the other will continue for a long time to enjoy more intimate relationships within their own areas. That is unavoidable. The point, however, is to develop a broader structure that links the foregoing in various regional or functional forms of cooperation.

… East and West will functionally come to cooperate—not through overt treaties, but through environmentalism, technocracy, and systems thinking. And this, we’re told, will unfold in two phases:

Movement toward such a community will in all probability require two broad and overlapping phases. The first of these would involve the forging of community links among the United States, Western Europe, and Japan, as well as with other more advanced countries (for example, Australia, Israel, Mexico). The second phase would include the extension of these links to more advanced communist countries.

Here’s my take.

The first phase involved the creation of an international organisation to facilitate coordination across the West, including Japan. That, of course, was the Trilateral Commission.

The second phase involved integration with the East, which came under the banner of Gorbachev’s Perestroika.

The emerging community of developed nations would require some institutional expression… setting up only a highlevel consultative council for global cooperation… a council of this sort—perhaps initially linking only the United States, Japan, and Western Europe…

That is the Trilateral Commission. Incidentally, co-founded by Brzezinski himself. The other co-founder?

David Rockefeller8.

And as for its objective:

Such a council would also provide a political security framework… Political security efforts would, however, in all probability be second in importance to efforts to broaden the scope of educational-scientific and economic-technological cooperation

So the real priority isn’t security—it’s standardisation: of education, science, technology, economics. All driven through cooperation, of course. And as for the framework:

… it may be desirable to develop an international convention on the social consequences of applied science and technology. This not only would permit the ecological and social effects of new techniques to be weighed in advance but would also make it possible to outlaw the use of chemicals to limit and manipulate man and to prevent other scientific abuses to which some governments may be tempted. In the economic-technological field some international cooperation has already been achieved, but further progress will require greater American sacrifices. More intensive efforts to shape a new world monetary structure will have to be undertaken

… applied science—and more specifically, applied systems analysis—will become the lens through which ethics, technology, and economic policy are managed. But of course, that also means censorship, scientific gatekeeping, and control over what qualifies as 'legitimate' inquiry.

And while we’re at it—why not reshape the global monetary order too??

Incidentally, this wasn’t left on the drawing board. In 1996, the ICSU introduced SCRES (Standing Committee on Responsibility and Ethics in Science), and in 1997, UNESCO launched COMEST (World Commission on the Ethics of Scientific Knowledge and Technology). Together, they established so-called ethics declarations to ensure that science and technology would serve only 'appropriate' ends.

And yes, those same ethics now govern healthcare professionals, who are expected to comply—without question—when told to inject people with totally safe and effective 'vaccines'… during a totally legitimate 'pandemic'.

And it’s in this context that the communist states are brought up again—this time with particular emphasis on Yugoslavia, which is clearly being positioned as the preferred model. But we still have the second phase of the plan to outline.

So what will the second phase look like?

Over the long run—and our earlier analysis indicates that it would be a long run—Soviet responsiveness could be stimulated through the deliberate opening of European cooperative ventures to the East and through the creation of new East-West bodies designed initially only to promote a dialogue, the exchange of information, and the encouragement of a cooperative ethos.

… okay, cooperation through East-West bodies... like the IIASA, perhaps?

But we also have:

The deliberate definition of certain common objectives in economic development, technological assistance, and East-West security arrangements could help stimulate a sense of common purpose

… a common purpose through security arrangements. Like, say, the SALT agreements, perhaps?

The underlying motivation for such a community is, however, extremely important. If this community does not spring from fear and hatred but from a wider recognition that world affairs will have to be conducted on a different basis, it would not intensify world divisions—as have alliances in the past—but would be a step toward greater unity.

OK, so perhaps not nuclear disarmament or other military affairs, but rather a common enemy… mystery intensifies…

A greater sense of community within the developed world would help to strengthen these institutions by backing them with the support of public opinion; it might also eventually lead to the possibility of something along the lines of a global taxation system

… which should be supported by continuous propaganda, leading to a condition where people will, for the purpose, eventually come to accept even a global tax ‘for the common good’… this really is turning into quite the headscratcher…

… the United States cannot shape the world singlehanded, even though it may be the only force capable of stimulating common efforts to do so. By encouraging and becoming associated with other major powers in a joint response to the problems confronting man's fife on this planet, and by jointly attempting to make deliberate use of the potential offered by science and technology, the United States would more effectively achieve its often proclaimed goal.

… and to this extent, we need to direct science for a joint purpose, striving to confront man’s fife on this planet… what could it possibly be…?

To sum up: Though the objective of shaping a community of the developed nations is less ambitious than the goal of world government, it is more attainable. It is more ambitious than the concept of an Atlantic community but historically more relevant to the new spatial revolution. Though cognizant of present divisions between communist and noncommunist nations, it attempts to create a new framework for international affairs not by exploiting these divisions but rather by striving to preserve and create openings for eventual reconciliation.

… achieved outside of democratic capacity, in a slow fashion, through international organisations, and it should create a new framework which eventually leads to global reconciliation. This is an enigma… what could it possibly be?

There is thus a close conjunction between the historic meaning of America's internal transition and America's role in the world. Earlier in this book, domestic priorities were reduced to three large areas: the need for an institutional realignment of American democracy to enhance social responsiveness and blur traditional distinctions between governmental and nongovernmental social processes; the need for anticipatory institutions to cope with the unintended consequences of technologicalscientific change; the need for educational reforms to mitigate the effects of generational and racial conflicts and promote rational humanist values in the emerging new society

… and the American society needs to be radically reshaped through reform, enabling NGOs possibility of closer… ‘cooperation’… with science employed to future predict, and with educational reforms, preparing the worker drone pupil for the world of Scientific Socialism… but what could possibly be the gateway?

The international equivalents of our domestic needs are similar: the gradual shaping of a community of the developed nations would be a realistic expression of our emerging global consciousness; concentration on disseminating scientific and technological knowledge would reflect a more functional approach to man's problems, emphasizing ecology rather than ideology…

Oh golly gee, how surprising. Not through ideology — but through… ecology.

Environmentalism.

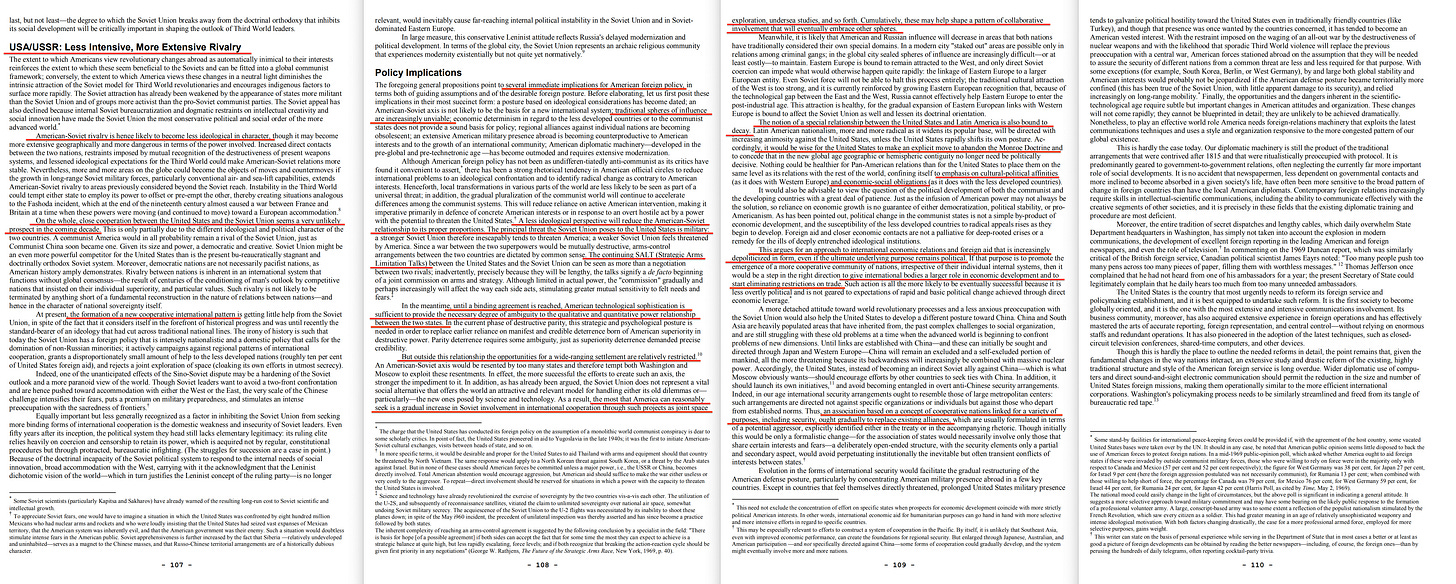

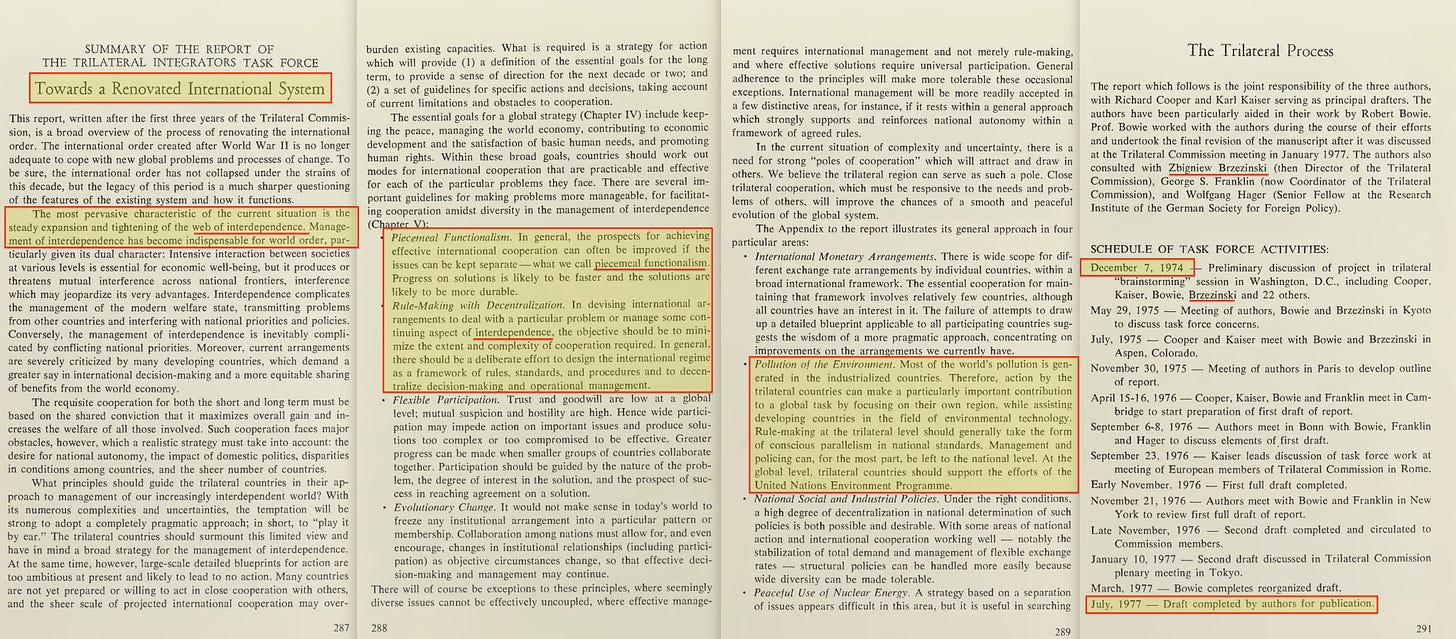

In 2010, Fulvio Drago published his paper ‘Dealing with an Interdependent and Fragmented World: The Origins of the Trilateral Commission‘9, through which we learn of its founding:

In the spring of 1972 David Rockefeller, inspired by the writings of Zbigniew Brzezinski, proposed the creation of the Trilateral Commission, where academic experts, economists, politicians and journalists from the three poles of the industrialized world— North America, Japan, and Western Europe—could meet to discuss the major problems of the international system in order to improve public understanding of such issues through the support of the media.

But we also see the emphasis on the inclusion of Civil Society actors, for the sake of consensus-building—a process designed to pre-shape the agenda itself. And to that extent, experts should be engaged, including:

According to Rockefeller, world leaders were not able to provide the public with a broad vision with long-term goals for electoral reasons. Instead, an organization of private citizens and experts not connected with political power could not only help to define more accurately a strategy to address the problems by placing them in a more general context, but also inform public opinion in order to build a consensus on new goals and strategies. The members of this group would come from the most advanced countries of the world capitalism, Japan, Western Europe and North America. The group had to include experts from different areas as, i.e., universities, the press, entrepreneurs, and the environmental movements.

Yes, including even experts with a background in environmentalism.

And how would all this be carried into play?

They also promoted more coordination between leading world economies, the development of alternative energies, and oil conservation policies. The tools for implementing these objectives were cooperation, multilateralism, and concerted decision-making within international organizations.

Through international organisations—the very same structures outlined by Leonard S Woolf in International Government (1916), which would, bit by bit, sap powers away from the sovereign.

And in terms of the environment, that’s precisely where the IUCN enters the stage.

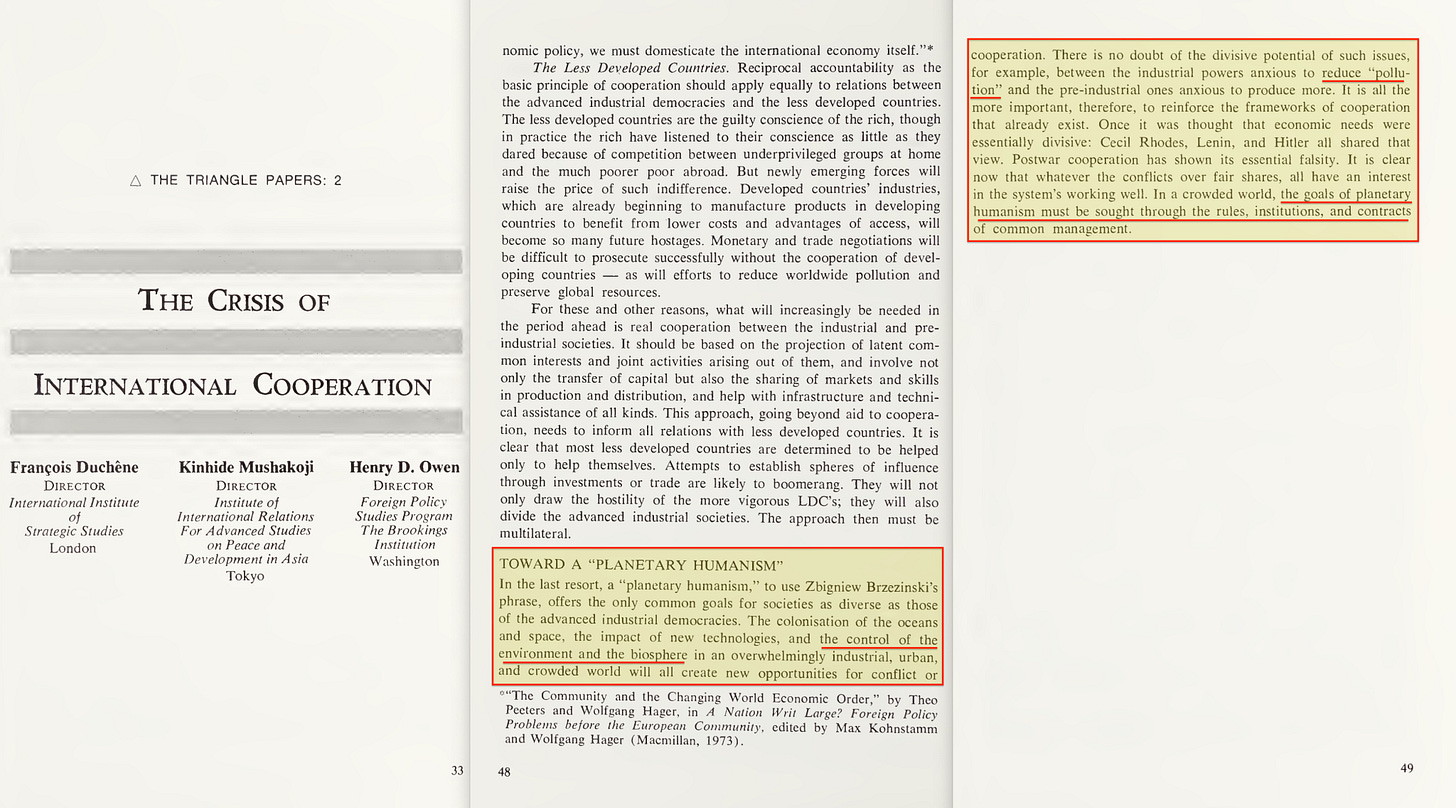

Next follows their Second Triangle Paper, which broadly carried a tone completely and utterly aligned with the narrative—the fusion of socialism with capitalism, of public labour with private capital—all for the common good.

The same report further echoes Brzezinski’s focus on Planetary Humanism, which allegedly provides the global, common goals — namely, the control of the environment and the biosphere. And the solution, naturally, is to be delivered through Woolf’s international organisations.

We also have a Trilateral Process task force beginning in 1974, with an emphasis on environmentalism, interdependence, flexible participation, evolutionary change, and—naturally—international monetary arrangements…

I could make a big song and dance about the Triangle Papers, but once you spot the pattern, it becomes undeniable. Regardless of how impressive their Aesopian framing is, once you see it—you see it everywhere.

But let’s instead return to May 23rd, 1972, with Henry Kissinger and Russell E. Train—both solidly within the Rockefeller sphere—and Richard Nixon, signing the US–USSR Agreement on Cooperation in Environmental Protection. The signature which, long-term, would quietly sink the West.

This agreement called for global modelling of the environment, which was facilitated just months later through the creation of the International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis. The IIASA would go on to work on environmental future predictions (of doom), operationalising the agreement which soon expanded to cover a wide range of global management concerns.

And by 1975, the IIASA were already drafting the first paper on carbon pricing—before anyone even knew if there was a problem at all..

Next followed the founding of the Trilateral Commission in 1973, after which the 1974 New International Economic Order10 quietly called for retargeted development aid—aid that came with strings attached. Recipient nations would have to accept the new terms, or aid would be cut off.

And the primary objective of these new terms was laid out by the IFDA’s Third System in 1978, with the IFDA also being the first to contextually use the term ‘Sustainable Development’.

As for the Third System—this describes the public–private–CSO model, where the civil society organisation defines the ‘common good’ in the name of development—or, naturally, ‘social or environmental justice’.

In 1982, Mexico failed to refinance her debt. That triggered the Latin American debt crisis, which in turn inspired Thomas Lovejoy’s 1984 Debt-for-Nature Swaps—a mechanism that, in essence, transfers prime lands into UNESCO Biosphere Reserves, from where they can be promptly monetised.

This topic, incidentally, was discussed at the 4th World Wilderness Congress in Denver, 1987, which explicitly called for a World Conservation Bank—a concept that would eventually materialise in 1991 under the name: the Global Environment Facility (GEF). The GEF then acted as the financial mechanism as the Rio Earth Summit launched both the UNFCCC and the Convention on Biological Diversity.

But back in 1987, Conservation International and The Nature Conservancy facilitated the very first Debt-for-Nature Swaps—essentially financial arrangements that require continuous refinancing… until the day comes when it’s no longer possible—at which point the collateral is transferred into the UNESCO Biosphere Reserve system.

And as for environmental NGOs? There’s no shortage of representation11 of those on the Trilateral Commission12.

Our Common Future then reframed the world as a system, ripe for adaptive management, while Agenda 21 in 1992 subtly introduced the world to the same public–private–CSO model. Meanwhile, the World Bank, under the banner of ‘Good Governance’, began pushing for civil service reform in exchange for development aid. By 1997, the UNDP followed suit—this time demanding electoral reform.

The culmination of this timeline arrives with Wolfgang Reinicke, who in 2000 published the model that would facilitate the Third System on a global scale, now under the more palatable label of ‘Trisectoral Networks’.

His co-authors—including everyone’s favourite supervillain, Klaus Schwab—featured a roster of Trilateral Commission members including even Jimmy Carter, all working toward one shared objective:

To facilitate the transfer of political rights, at the global level, away from the sovereign, and into the hands of international organisations—first laid out in detail in 1916 by the Fabian Society’s Leonard S. Woolf in International Government.

But the model itself traces further back—to 1899, with Eduard Bernstein’s public–private partnership for the common good, which in turn builds directly on Julius Wolf’s 1892 report, where the global gold clearance mechanism—later used by the BIS at its founding in 1930—was first proposed

The bottom line is this:

D(eception)-Day outlined the operational mechanism.

The Third System provided the administrative control.

But the altruistic elite still required a forum—a discreet platform where they could gradually fuse NGO control into both public and private sectors, entirely outside the bounds of democratic legitimacy. And David Rockefeller responded to that call by founding the Trilateral Commission.

In these more modern times, the Trilateral Commission now calls for a ‘new spirit of capitalism’, based on ‘moral’, even ‘inclusive capitalism’—allegedly to address systemic issues of social injustice. Though you could, perhaps more accurately, call that Eduard Bernstein’s Evolutionary Socialism (1899)—itself inspired by Julius Wolf’s 1892 framework.

Incidentally, Wolf was Rosa Luxemburg’s PhD chair, and Bernstein a noted revisionist Marxist.

But I’m sure those are just coincidences.