Dumbarton Oaks

You may wonder—how did the United Nations come to be?

But the more interesting question to ask is actually—what ultimately happened during the final years of the League of Nations?

The negotiations that led to the establishment of the United Nations officially began with the release of the Atlantic Charter1 in 1941. While the US Navy’s history page mentions the event, it interestingly omits what may be its most important aspects2.

The charter outlines the Lend-Lease Act3, the supply problems of the Soviet Union, and the danger presented by Hitler to ‘world civilization’, before detailing eight ‘certain common principles’ aimed at creating ‘a better world’.

The first three relate to ‘no aggrandisement’, ‘no territorial changes’ and ‘respect the right of all people’, while principles 6 and 8 concern ‘establishing peace’ and the ‘abandonment of the use of force’. The final three are the most significant.

Principle 7 calls for ‘such a peace should enable all men to traverse the high seas and oceans without hindrance‘, which, in its narrow interpretation, relates to maritime freedom. However, it was only in 1948 that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights4 arguably called for the next step towards free movement. Thus, it could be considered a precursor.

But the two principles of primary interest are items 4 and 5:

… they will endeavor, with due respect to their existing obligations, to further the enjoyment all states, great or small, victor or vanquished, of access, on equal terms, to the trade and to the raw materials of the world which are needed for their economie prosperity…

Followed by:

… the fullest collaboration berween all nations in che economic field…

And why are they of interest? Simple—because these two align entirely with the neoliberal trade policies advocated by Leonard S Woolf’s 1916 report published by the Fabian Society; International Government.

Finally, the charter outlines the need to disarm rogue states, in this regard obviously referring to Nazi Germany:

… pending the establishment of a wider and more permanent system of general security, that the disarmament of such nations is essential…

The Atlantic Charter led to the Declaration by the United Nations5 in 1942. Truth is, however, it’s essentially the same document. The primary difference here is that it’s co-signed by the Soviet Union.

Then came the Casablanca6 Conference7, 1943, primarily relating to military activities. Though it is of high interest to historians, it is not particularly relevant to our focus here.

Next came the Tehran8 Conference9, 1943, the document of which outlines the ‘three powers’ that would strive to work together post-war. It also invites all ‘democratic nations’ into the ‘world family’—never mind that one of those three nations was Stalin’s Soviet Union.

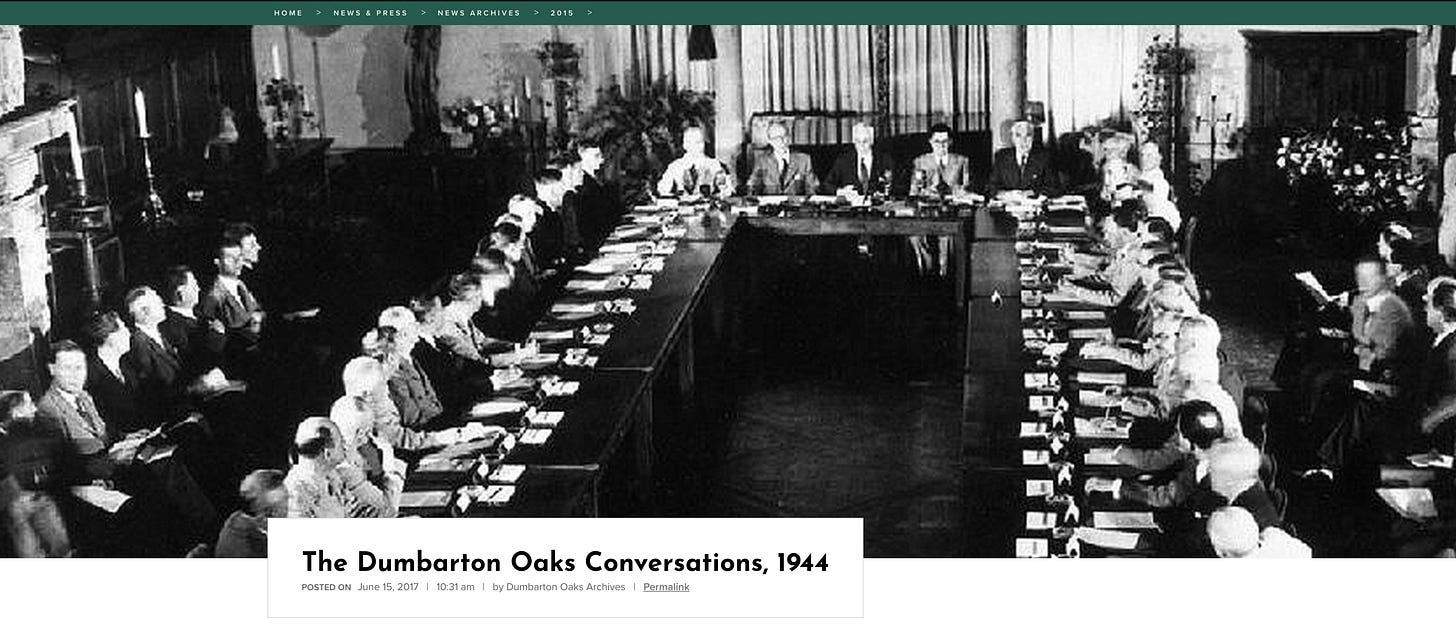

Dumbarton Oaks, 1944 was the event of primary significance. The draft can be located in the Royal Institute of International Affair’s bulletin of October, 194410 which carried the full text of the British working paper. The first few pages are largely boilerplate; a new international organisation titled the United Nations is proposed, primary objective is to maintain international peace and security, co-operation, solving international economic, social and humanitarian issues, and establishing a centre with the aim of:

‘… harmonizing the actions of nations in the achievement of these common ends‘

The organisation will be based upon principles of sovereign equality, peace and security, with disarmament and the regulation of armaments as notable inclusions.

Next, the document details procedures for the election of non-permanent members to the permanent institutions, one of which is the International Court of Justice. It then abruptly expands into the political sphere in areas of co-operation, further broadening its scope through the inclusion of ‘other specialised agencies’. This approach is common, they begin with something on the surface appearing reasonable, and then proceeds to broaden the scope almost immediately.

Next follows details relating to the Security Council, which issued a global call for the least future expenditure on armaments, followed by a repeated call for their regulation. The council is also tasked to ‘determine the existence of any threat to the peace’, and ‘make recommendations or decide upon the measures to be taken to maintain or restore peace and security‘. To this end, ‘the security council should be empowered to determine what diplomatic, economic, or other measures not involving the use of armed force’, though it later calls for member nations ‘to make available to the Security Council… armed forces, facilities and assistance‘.

The ‘good stuff’ in the document begins in Chapter IX, ‘Arrangements for International Economic and Social Co-operation‘ where the associated Economic and Social Council should ‘make recommendations on its own initiative with respect to international, economic, social and other humanitarian matters’, and to ‘… receive and consider reports from… other organisations or agencies brought into relationship with the Organisation, and to coordinate their activities…‘

It’s interesting phrasing because, in contemporary terms, those ‘other organisations’ (General Consultative Status NGOs) effectively dictate the ‘common good’ through Trisectoral Networks—with ECOSOC managing these efforts.

In terms of organisation and procedures, the ESC ‘should set up an Economic Commission, a Social Commission, and such other Commisions as may be required. These Commissions should consist of experts’. Additionally, the ESC should ‘make suitable arrangements for representatives of the specialised organisations or agencies to participate…’

In other words, this outlines the organisational rules for the inclusion of exactly those NGOs that would eventually come to dominate international affairs—exactly as envisioned by Leonard Woolf in 1916 when he penned the Fabian Society published document, International Government.

Today, we see no fewer than 6,468 organisations registered with ECOSOC11 in this capacity, of which 132 hold General Consultative Status, allowing them to ‘place items on the agenda’ per Wolfgang Reinicke’s Trisectoral Networks.

And these are the organisations that now work to define the global ‘common good’.

The American Observer12 covered the conference as well, stating that the creation of the United Nations was necessary to prevent a third world war and that the main challenge lay in designing an organisation acceptable to all three major powers. The article lists the Senate’s acceptance of the Versailles Treaty as a mistake and references the 1943 Moscow Declaration, which called for the creation of a general international organisation to maintain and establish peace. While this organisation was to adopt certain features of the League of Nations system, it did not call for the establishment of an international army—though the Soviet Union was willing to comply. However, a world court was proposed, leading to the revival of the legal machinery of The Hague.

Finally, the article highlights that some voices have questioned this concentration of power, noting that this is the second attempt at such an organisation—the first being the ill-fated League of Nations13.

And the Moscow Declaration14 of Oct 30, 1943, calls for an international organisation to be etablished for the maintenance of peace and security15.

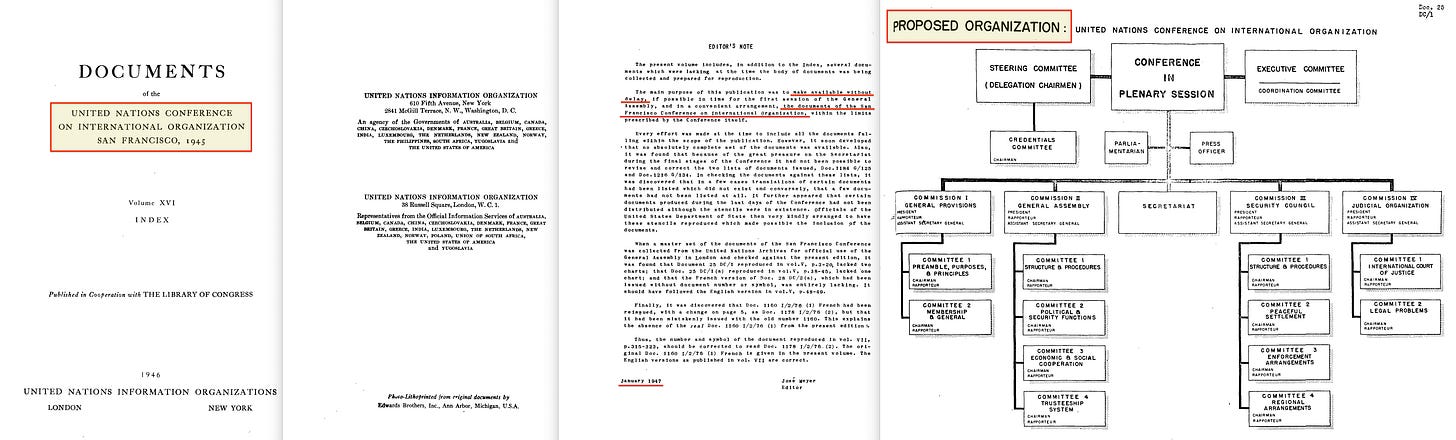

Through the outcome document16 of the 1945 conference leading to the United Nations, we can observe a neatly arranged organisational structure.

In fact, they seem somewhat obsessed with these flowcharts.

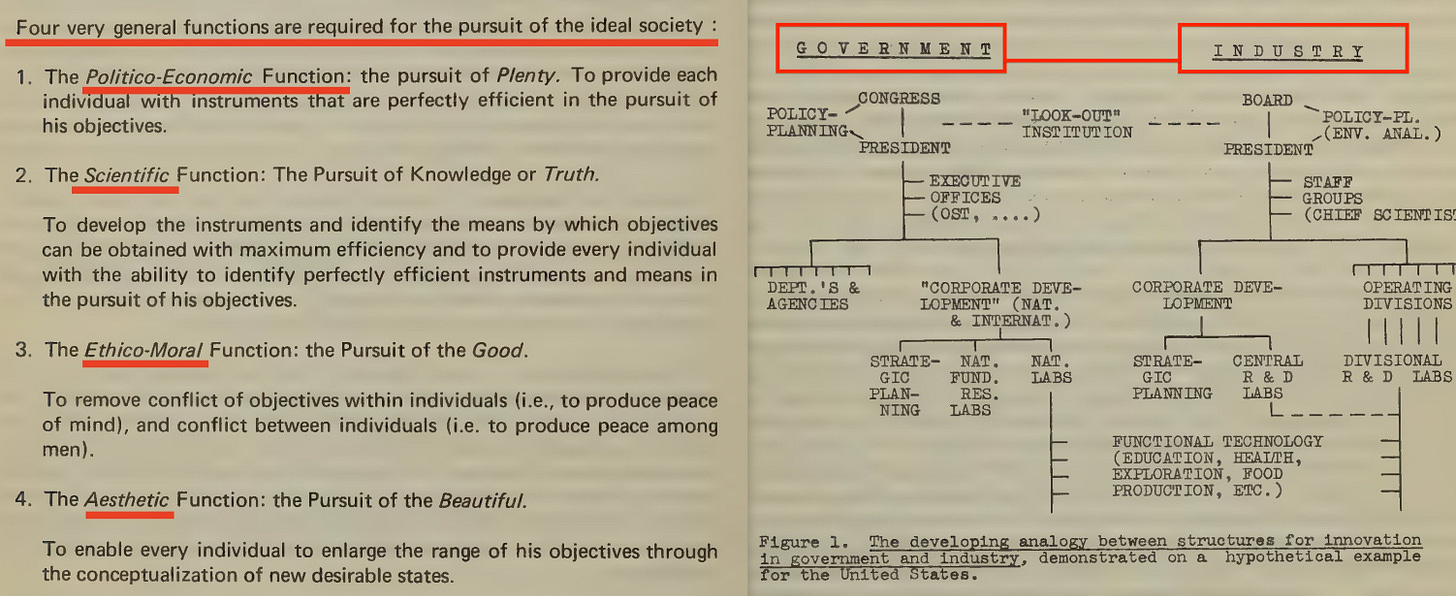

… they somewhat remind me of Erich Jantsch’s outline in Perspectives on Planning from 196817, which draws parallels between corporate and public governance. I previously argued that this was a likely precursor to Freeman’s Stakeholder Approach from 1984—a connection that makes complete sense given the outline of developments in the field of systems theory we discussed in Cybernetic Thomism.

In 1946, a bibliography on World Organisation was released18. It serves as a decent reference document, which is why I include it—but beyond that, it isn’t of much use.

What is further notable about Dumbarton Oaks is that Alger19 Hiss20 was one of the key American figures involved. Although he was not the sole contributor, his participation stands out—especially given that he was later outed as a Soviet spy21. And that appears entirely fitting—but more on that later.

But while these developments marked the launch of the United Nations, this occurred against the backdrop of the League of Nations being retired. As we have already discussed, the United Nations was, to a large extent, modelled on the League of Nations. But to what extent? That’s where the next report comes in—‘Report On The Work Of The League During The War‘22—which begin by remarking:

‘The League of Nations as an organisation no doubt had faults, but it is dangerous nonsense to sav that war came because of those faults. The League did not fail; it was the nations which failed to use it.‘

So, according to this view, there was supposedly nothing wrong with the organisation itself; rather, the failure lay with the nations that did not fully embrace Leonard S. Woolf and Alfred Zimmern’s remarkable creation.

‘The necessity for the so-called “technical" services—economic, financial, transit, health, narcotic drugs, etc—being pursued remained as great as ever.‘

And, as the claim goes, the demand for the various services provided by the League of Nations remained just as strong.

‘The continuation of such activities—apart from their momentary or durable intrinsic value was also to some extent a challenge to the forces of disorder and would, it was expected, ultimately help to provide a basis for a reconstructed world organisation.

In other words, while the League of Nations was formally retired, there was no need to dissolve its individual organisations and agencies—including the International Labour Organisation—which would continue under the new framework.

The report goes into further detail on this point:

‘Their intimate knowledge of affairs of the League administrations indicates their special competence for the new duty they have now undertaken. It will not be a simple task, whatever method is adopted, for, while it is desirable to expedite the transfer or termination of League functions, it is unkely that a worldwide organisation covering many fields of human activity can be closed down with the speed and procedure of a limited liability company. Political, legal and administrative problems wil arise and, in most cases, satisfactory solutions must be found before the organs of the League and the Permanent Court of International Justice are replaced and the International Labour Organisation is estabished on a new foundation’.

Political, legal, and administrative issues—none of these pose a problem if all activities are simply transferred. Besides, the process must move quickly, ensuring that diplomats have little time to scrutinise the transition.

‘The League has many assets which should be preserved for the benefit of its successor and for the benefit of world co-operation.‘

And with that, we should also accept a continuation of its assets, which include:

‘The substantial proverties of the League. its numerous offices and buildings specially constructed for housing a great international organisation, its magnificent Library, represent a considerable financial value; still more, they represent facilities for working in the international field which should be preserved for similar purposes.‘

… its offices, library, buildings…

‘Whatever the problems connected with the transfer of activities, assets and liabilities from one international organisation to another, it is thought that Governments generally will recognise the value of the heritage. Men and women who have been trained for years to serve internationally will be available for service with the United Nations.‘

… staff, heritage, training…

‘There seems to be no reason why the archives of the League-the result of twenty-five years of collecting, classification, and study-should not be a foundation stone for the new Secretariat.‘

… information system, its archives, and records in general…

‘The League Library… a generous gift in 1929 by Mr. John D. Rockefeller, Junior‘

… oh, what are the odds?

But we’re not quite done:

‘Powers and Duties attributed to the League of Nations by International Treaties‘

Powers, duties, …

‘"The international Labour Urganisation aso is closelv connected with the League.‘

… and the ILO, which continues to this day.

‘… the new World Organisation is, in many respects, able to "take over" from the old.‘

In other words, the United Nations is, in many ways, simply a continuation of the League of Nations under a different name.

‘The allocation of work between the Security Council and the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations has been made on lines which, to a great extent, correspond to the recommendations made by the “Bruce Committee” and adopted by the League in 1939‘

… and in 1939, a committee was formed to explore a reformed system for the League of Nations. This committee developed an organisational format that essentially became the blueprint for the United Nations Security Council and the Economic and Social Council—what we now know as ECOSOC23.

And Chapter 1, which addresses economic, social, and transit issues, opens with a zinger:

‘In 1939, the Assembly observed that "the present condition of the world renders it all the more necessary that the economic and social work of the League… should continue on as broad a basis as possible"… Bruce Committee… proposed the creation of a Central Committee to unify the economic and social work of the League…the Economic and Social Council, which is to be set up under the Charter of the United Nations, is based directly on the League's experience and is, in its conception, similar to the Central Committee projected by the League in 1939/40‘

See, not only did the Bruce Committee create the blueprint for ECOSOC and the Security Council, but they also proposed that all League of Nations efforts in the spheres of economic and social activity should continue.

‘It was accordingly decided to concentrate the work on current events in the three key periodical publications… the detailed statistics of commercial and central banks which had previously been published as part of the memoranda on Money and banking…The plan, which in a slightly modified form was approved by the Economic and Financial Committees in 1942, was based upon three guiding principles; First, that the future must inevitably be built on the past…‘

… and the plan was accepted. The future United Nations (in this regard, ECOSOC, though it applies more broadly) was to be built upon the League of Nations, even down to the provision of information—information, notably, in this regard of particular use to central banks.

‘The broad aim of the programme was set out by the Economic and Financial Committees in the following terms: ... the organs of the League should provide such expert guidance as they can to assist Governments in implementing the policies formulated in the Atlantic Charter‘

In fact, League of Nations staff were to help implement the Atlantic Charter—the very document that set the stage for the United Nations. And as for a sudden staff shortage? That was alleviated through a generous and atruistic offer by… well, Rockefeller. Who else24?

In fact, Rockefeller’s particular brand of altruism went beyond just providing staff:

‘Other officials from Geneva joined them in 1941, and a staff of economists and statistical and secretarial assistants was gradually recruited in America with the aid of a generous grant from the Rockefeller Foundation.‘

And if we now have staff, offices, buildings, funding, information, blueprints, and thus an all-but seamless continuation of operations, what else is required?

‘… a number of publications were issued many of which had been begun earlier in 1939. Amongst these may be mentioned: Balances of Payment, 1938; International Trade Statistics, 1938; International Trade in Certain Kaw Materials and Foodstuffs by Countries of Origin and Consumption, 1938…‘

Lots and lots of ‘independent research’—supporting the preconceived conclusions on finance and economics.

‘Attention is naturally devoted, in the Year-Book, to subjects of immediate interest, such as territorial changes which have occurred at various stages of the war, Government receipts, expenditures and indebtedness (including war expenditure in the principal belligerent countries, currency measures adopted and currency equivalents established—more particularly in the former occupied territories of Europe, Africa, and Asia.‘

Government receipts help with future fiscal budgeting, and currency measures assist in understanding macroeconomic outcomes. But for that information to truly ‘gel’, what’s needed is data relevant to the central banks.

‘Among the subjects for which relatively complete national statistics continued to be avalable during the war were currency and banking. A compendium of the world's central and commercial banking statistics entitled Money and Banking was accordingly issued from Princeton in 1943, and again in 1945, each issue embracing approximately fifty countries.‘

So, with a comprehensive overview of fiscal and monetary history, a structural blueprint, and continuity across multiple fields, what comes next?

‘Three issues have been published since the outbreak of war, each containing not only a general review of the world economic developments in the period covered but also special chapters on raw materials, industrial and food production, on consumption and rationing, on finance and banking, on price movements and price control, on international trade, on the transport situation, etc.‘

Resources, including food, alongside trade-related information. In fact, a summary of the programme of work addressing post-war challenges is organised under four general headings:

Reconstruction and relief

Development, in other words.

Trade and trade policy ;

Exchanges between nations.

Economic security ;

Intra-nation financial stability.

Demographic questions.’

In other words, population growth—an issue that had been a key focus for Rockefeller since at least 192725, if not earlier.

‘… the following five studies dealing with relief and reconstruction… International Currency Experience (1944), …A study on the Control of Inflation after the 1914-1918 war is in preparation‘

… meaning that five studies were dedicated to development alone.

‘This study examines, accordingly, the operation and breakdown of the gold and gold-exchange standard; the use of gold reserves and foreign balances for international settlements; devaluations and fluctuating exchanges; the emergence of currency groups such as the sterling area, the gold bloc, etc. ; the trend of central banking practices and domestic credit policies generally; the rise of exchange stabilisation funds; exchange control and bilateral clearing arrangements, etc.‘

… and once again, we find ourselves back with Julius Wolf, who pioneered the gold clearance mechanism that was later adopted by the Bank for International Settlements. He first outlined this concept in 1892—just a few years before serving as Rosa Luxemburg’s PhD chair.

‘The conclusions of the survey point the way to a system in which exchange stability and increased trade are promoted through international co-ordination of domestic policies for the maintenance of economic activity.‘

… harmonisation of national policy. Conveniently, this aligns perfectly with the narrative of Leonard Woolf’s International Government, further centralising policy-making in fewer hands—hands that, notably, remain outside any democratic oversight.

‘Five studies have been prepared and issued by the Department on the subject of trade and trade policy: Europe's Trade (1941), The Network of World Trade (1942), Commercial Policy in the Interwar Period (1942), Quantitative Trade Controls (1943), and Trade Relations between Free-market and Controlled Economies (1943)… Europe's Trade was an attempt to consider what was the part played by Europe in the trade of the world and in the international transfer of funds in the thirties, how far Europe was dependent on external markets, and how far one area in Europe was complementary to another.‘

And this analysis of interdependencies can be summarised quite simply—yet another topic we’ve touched on before. Europe, at the time, would have provided a high-resolution overview of macroeconomic activity, whereas the rest of the world…

‘Its sequel, The Network of World Trade, is primarily concerned with the essential unity of world trade and with the worldwide system by which payment transfers were effected.‘

… would naturally be of lower detail. But when we talk about IO Analysis, we are simply describing a method of surveillance—and that surveillance data is just a tool.

‘In Quantitative Trade Controls, which was prepared by Professor G. Haberler in collaboration with a member of the Economic, Financial and Transit Department, consideration is given to the questions: What were the forces that induced Governments to adopt quantitative trade controls (quotas, etc.) in the inter-war period? What are the relative advantages and disadvantages of such measures compared with tariffs?‘

Because once that surveillance data is gathered, the next logical step is to understand how monetary flows shift in response to changes in the economic environment.

And those environmental changes are precisely what trade controls regulate—exactly what Haberler addressed above. Trade controls themselves form a system:

‘Trade Relations between Free-market and Controlled Economies, by Professor Jacob Viner, deals with what may prove to be one of the major problems of commercial policy-namely, that of the trading relationships between countries if some subject their foreign trade to direct regulation and others desire to avoid such controls and to influence the free play of the price mechanism only or mainly by tariffs. In his last chapter, Professor Viner sketches the broad outline of what might constitute the agenda of a post-war conference on commercial policy.‘

We now have:

Neoliberal trade policies (pushing free-market principles),

Protectionist policies (maintaining national controls), and

Tariff-based funding systems, which historically sustained entire national economies.

The last point is especially relevant to the United States, which, until the early 20th century, funded itself primarily through import and export duties.

‘Arrangements were made by the Mission in Princeton under which the major part of the programme of demographic studies laid down by the Demographic Committee in 1939 was taken over by the Office of Population Research of Princeton University, under the general editorship of the Director of the Economic, Financial and Transit Department.‘

I bet you don’t have the foggiest who funded them26.

With an overview of trade policy (and the explicit aim of harmonising international legislation), the next focal point logically shifts towards:

‘The task of recommending policies that might be employed "for preventing or mitigating economic depressions" was entrusted by the Council to a small Delegation under the chairmanship of Sir Frederick Phillips in 1938. This action was a natural development of the work of the Economic and Financial Organisation, which had, for a number of years, been carrying out a programme of research into the nature and causes of economic fluctuations.‘

… in other words, preventing economic downturns. And this is of particular importance, because:

‘A draft report on this subject was prepared by the Secretariat and approved by the Delegation in April 1943. The final text was published under the title The Transition from War to Peace Economy… influenced the thinking of statesmen and officials concerned with economic policies.‘

… wartime economics, by necessity, dictate massive increases in public spending. But when that spending is suddenly pulled back—and higher taxation is introduced to address wartime deficits—the economy risks collapsing into a tailspin—as neither the state nor the private sector has any money, and the vast industrial complex built around the war effort suddenly loses its purpose.

This inevitably impacts the individual, leading to:

‘(4) That society distribute, as far as possible, the risk to the individual resulting from interruption or reduction of earning-power;‘

… which, in practice, means the introduction of a social safety net. This distributes risk—but at the expense of curtailing reward through higher levels of taxation.

But, as the argument goes, to ensure an orderly transition from a wartime to a peacetime economy, what is required for industry to function is:

‘(6) That the liberty of each country to share in the markets of the world and thus to obtain access to the raw materials and manufactured goods bought and sold on those markets is promoted by the progressive removal of obstructions to trade ;‘

Free trade—exactly as Leonard Woolf envisioned. Neoliberal trade policy, over time, inevitably dissolves borders, as sovereign nations are forced to progressively harmonise trade policies to remain competitive. If one country refuses, another gains an economic advantage—making alignment almost unavoidable. Free movement, formalised through the UDHR in 1948, represented a major step in this process.

But beyond neoliberal trade policy, the report also advocated for:

‘The report, as finally approved—a document of some 340 pages—was published in April 1945, under the title Economic Stability in the Post-war World… this report emphasises the essentially international character of business cycles and the need, therefore, for collective action to prevent or mitigate economic depressions.‘

… coordinated policy and action to regulate business cycles—one key component of which is:

‘The Delegation emphasises also the crucial part played in depressions by fluctuations in investment and in the spread of depressions from country to country by fluctuations in foreign investment…‘

… fluctuations in investment, which are ultimately dictated by fiscal policy and broader macroeconomic performance.

Ergo, what this indirectly calls for—if depressions are to be prevented—is the synchronisation of fiscal policy across nations.

‘"The object of anti-depression policy must be to maintain aggregate demand. Any one of these constituents of aggregate demand can theoretically make good a falling-off in any other."‘

And to achieve this, Keynesian countercyclical economic policy is required27. The term aggregate demand frames business activity in terms of GDP, with the government stepping in to increase public spending during downturns and reduce spending during booms—theoretically smoothing out economic cycles and eliminating boom-and-bust dynamics.

However, aggregate demand as a concept lacks precision. In practice, an incompetent government could easily substitute legitimate private investment with wasteful spending—for instance, by pouring funds into replacing windows28, only for delinquents to use them for target practice (aka the broken window fallacy)29.

Keynesianism, in short, politicises the economy. It also tends to result in a gradual accumulation of public debt. In theory, it doesn’t have to—but in practice, it almost always does. Why? Because any government that dares to cut spending—even during economic upswings—is promptly punished at the ballot box.

And so, even the so-called great Keynesian Gordon Brown30 who should have been accumulating reserves during the good years—didn’t save a penny31.

But we’ve gone almost two pages without a blatant call for harmonised policy, sooo…

‘… it is emphasised, no country can hope to pursue its policies in isolation without seriously impairing its standard of living.‘

And this should be facilitated through action in five key areas:

‘(a) The adoption of more liberal and dynamic commercial and economic policies;‘

Translation: international monetary, fiscal, and trade policy harmonisation.

‘(b) The creation of an international monetary mechanism;‘

Ah yes, the implied call for what would become the International Monetary Fund32.

‘(c) The creation of an international institution which will stimulate and encourage the international movement of capital for productive purposes and will, so far as possible, impart a contra-cyclical character to this movement;‘

Oh gee, that sounds an awful lot like the World Bank. While the IMF focuses on short-term balance-of-payments stability and exchange rate policies, the World Bank deals with long-term economic development and infrastructure investment—serving as a counter-cyclical force, particularly in underdeveloped and crisis-hit economies.

And, as it happens, both of these institutions were established in 1944 at Bretton Woods33.

‘(d) The creation of a buffer-stock agency;‘

This one is a bit more obscure. If it refers to monetary stability, then the closest match would be the IMF or Keynes’ International Clearing Union (ICU) proposal34—which aimed to stabilise global trade imbalances through a managed international currency system.

However, if it refers to commodity price stabilisation, then it connects to early discussions on commodity agreements and food security initiatives, later linked to the World Bank and the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization).

‘(e) The international co-ordination of national policies for the maintenance of a high and stable level of employment.‘

… and that aligns almost perfectly with the International Labour Organization (ILO)35.

‘The co-ordination of national policies should, it is recommended, be achieved by " the appointment of a central advisory body of recognised competence as a part of the general international organisation; studying the policies… studying the fluctuations… making available to Governments its views about policies which might be pursued in order to revive or maintain economic activity;‘

Coordinated national bank policies? That goes through the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). And as for fiscal policy:

‘… joint discussions between itself and representatives of Governments and of international bodies concerned with economic policy;‘

That requires an international panel of ‘experts’—unelected, well-connected insiders, brandishing expert advice with absolutely no democratic oversight.

‘… recommending to the appropriate organ of the United Nations joint discussions among Governments, when such a course proves advisable, with a view to formulating common policies against the common enemy which depressions constitute.‘

… in other words, fiscal policy harmonisation should flow through these ‘experts’, ensuring that economic decision-making remains firmly above and beyond democratic influence.

We could continue in the same vein through Chapter 2, titled ‘Questions of a Social and Humanitarian Character’, but I fail to see the point. It’s more of the same, just applied to different domains—health, the international drug trade, slavery, and migration.

There’s also a later chapter on administrative mandates, which mostly concerns the governance of territories under colonial control.

However, the ‘health question’ section does introduce vaccines and preventative medicine as key solutions—foreshadowing the World Health Organisation and specifically, the future role of global health governance.

Finally, the chapter on ‘Intellectual Cooperation’36 concerns the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation (ICIC)37. It details a series of studies covering international relations, social sciences, the spread of information, unemployment among intellectuals, educational problems, exact and experimental sciences, the fine arts, literature, libraries, intellectual rights, and work of the National Committees on Intellectual Co-operation.

For the record, the ICIC received French assistance to establish an executive branch, the International Institute of Intellectual Cooperation. However, while funded by the French government, the IIIC maintained an autonomous status—a detail that would later prove significant.

When the ICIC and IIIC both closed their doors, their activities were transferred to UNESCO—with the ICIC contributing the intellectual mission and the IIIC providing the administrative and operational structures.

In other words, while the ICIC provided the vision, the French government-funded IIIC became the administrative mechanism that UNESCO ultimately adopted.

So what does that mean? To understand, let’s step back to 1916 and Leonard S. Woolf’s International Government. Because he makes the idea clear:

Through neoliberal policies like free trade and open borders, national distinctions will gradually fade away, with economics serving as the facilitator. For example, if neighbouring countries like Norway and Sweden have wildly different policies, even the smallest differences in trade policy could provide an economic advantage to one country over the other through migration. Over time, these differences will tend to disappear, not just for smaller countries, but also for larger ones. As a result, neoliberalism will break down national policy differences, leading to a singular policy applied across the globe.

In this process, as national sovereignty gradually withers away, it becomes crucial that policy advice is monopolised through ‘expert panels,’ ‘information clearinghouses,’ and—above all—international organisations that answer to no voters whatsoever. This facilitates the transfer of power away from the individual nation-state, directly into the hands of NGOs that operate in specialised fields—such as the IUCN in environmentalism or Human Rights Watch in humanitarian concerns. These organisations will flag major transgressions, place them on the agenda with the United Nations, which will then develop strategies to address the issues—without any direct input from voters.

The process that started in 1916 through Leonard S. Woolf did not originate entirely with him. The idea actually traces back to Eduard Bernstein, who in 1899 published ‘Evolutionary Socialism’38. In his work, Bernstein suggested the creation of cooperative structures and proposed a ‘mediator approach’ to decision-making, especially in balancing the interests of labour and capital—essentially injecting a middle-man into the process.

The objective? To achieve socialism gradually through democratic reforms rather than by violent revolution. If that sounds familiar, it's because others picked up on this concept as well39.

Bernstein was influenced by Julius Wolf, the PhD chair of noted communist Rosa Luxemburg40, who lost her life following the Spartacist Uprising in 1919. Wolf analysed the dynamics between socialism and capitalism and, in 1892, through his work ‘Sozialismus und kapitalistische Gesellschaftsordnung’41 proposed a structured financial clearing mechanism—a gold clearance system—to manage international economic interdependence. This mechanism sought to facilitate global financial stability by offering a system of clearing transactions that would help manage the flows of capital and trade between nations.

Wolf in 1899 penned ‘Der Kätheder Socialismus und die sociale Frage‘42, in which he explored the necessity of intermediary institutions to balance and streamline international economic exchanges. He argued that effective economic integration requires both financial tools and supportive governance structures, with the tension between labour and capital bridged through mediating mechanisms.

But even before that, in 1895, through ‘Die Steuerreserven in England und Deutschland’, Wolf argued that monetary and fiscal challenges in a globalised economy require structured, intermediary institutions43. By linking fiscal instruments with earlier proposals on monetary clearing, he presented a comprehensive approach to economic governance.

And he in ‘Fünf Briefe über Marx an Herrn Dr. Julius Wolf’44 further discussed how economies could be interlinked, not just through trade, but also via coordinated financial and fiscal policiess.

And it was Wolf’s 1892 gold clearance mechanism that the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) adopted upon its founding in 1930, with the goal of the BIS being to become the ‘mediator’ in all matters relating to central bank clearing—thus formalising his vision for global economic coordination.

Bernstein and Wolf shared a common view on cooperatives and the ‘mediating approach’, a perspective similarly embraced by Franz Oppenheimer. This approach, some might argue, was seen as a way to facilitate the transition to Utopian Socialism.

In this regard, Oppenheimer sought to break monopolies, starting with the concentration of land. His focus was on dismantling concentrated power structures, particularly those in land ownership, as a means of achieving a more equitable society. This was part of a broader vision to restructure society through cooperative economic models, bridging the divide between capital and labour.

Yet, what he failed to mention was that the eventual change in land ownership status primarily would benefit UNESCO, whose Biosphere Reserves alone today hold reserves the size of Australia.

These cooperatives are also linked to Lenin’s New Economic Policy, which placed the Communist Party in the role of the ‘mediator’, outlining policies to ensure that public labour and private capital could cooperate—ethically. The NEP represented a shift in policy, allowing private elements to coexist with socialist principles, in order to rebuild the Russian economy after the turmoil of the revolution and civil war. By inserting the Communist Party as a mediating authority, the policy aimed to tame the best aspects of socialism and capitalism, while ultimately keeping both on a tight leash under centralised, communist party governance.

But, wait, we’re not done. In 1919, alongside the League of Nations, something else took off—scientific unions including the International Research Council (IRC)45, which eventually became the International Council of Scientific Unions. This organisation was designed to become Woolf’s international organisation operating outside of public accountability in the sphere of scientific research.

And in 1946—almost as soon as UNESCO opened its doors—the two scientific socialists—Viktor Kovda and Joseph Needham—ensured them virtually becoming the ‘S’ in UNESCO.

In 1969, the ICSU formed the Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE). And it was they who created the entire blueprint for UNEP’s Global Environmental Monitoring System in the early 1970, marking the official launch of global surveillance… which incidentally Moynihan suggested NATO should run…

… and in this context, the involvement of Kovda… kind of gives away what the September 17, 1969, Moynihan Memo was really about.

The newly founded UNESCO in 1946 requested an ‘International Resources Office’46. This request, incidentally, was first floated at the 1941 ‘Science and World Order’ conference, which was, in no uncertain terms, a crass advertisement for scientific socialism. As for the draft related to the said resource office—that was penned by none other than John Burdon Sanderson Haldane47, who not only was a convinced communist but also contributed to the 1942 document, ‘Science and Ethics’, outlining that the direction of evolution should be guided through ethics—essentially presenting the same argument made by T.H. Huxley in 1893.

In other words—when the League of Nations in 1919 was founded, it was to facilitate the drafting and implementation of policy to be implemented globally. This was to travel through international organisations (NGOs) outside of democratic accountability, where expert studies would be fabricated through ‘the best available scientific consensus’, and thus the ICSU.

And while the quasi-communist conference, ‘Science and World Order’ created a demand for an International Resources Office, the ICIC and IIIC folded into UNESCO in 1945, who in 1946 not only included the ICSU in its process, but further re-issued the call for said International Resources Office, which advocated for the accounting of natural resources as part of a broader effort to manage and regulate the use of the world's natural resources—including biological—aligning with the aims of the broader agenda within UNESCO at the time.

And in 1948, Julian Huxley left to form the IUPN, who in 1956 were briefly renamed to the ‘International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources‘48.

In other words—the IUCN is the manifestation of the International Resources Office, the ICSU (now ISC) fabricates the ‘best available scientific consensus’, the Collegium International puts a Bogdanov’esque Empiriomonistic spin on the data, converting this into an ethical imperative, which is then codified into legislation, translates into a science-direction by the WAAS, encoded into the arts and moral education through UNESCO, where ie the Laudato Si is evidence that Hermann Cohen’s principle of using religion as a vehicle of moral programming is very real.

And when the United Nations was formed—broadly, as a continuation of the League of Nations—practically every step of that pipeline had already been planned.

I could even in final throw in that even Silent Weapons for Quiet Wars align with this, given its inclusion of economic shock testing to determine indirect economic reverberations through the economy.

And with that said, here’s a chronology of the major events which led to the world the way it is today, where ‘science’ of sketchy quality, which you’re not allowed to review, through the United Nations is used by the IUCN to set global policies—without any democratic principles involved in the process.

And as for Dumbarton Oaks and the claim that the world decided to come together because of Nazi atrocities. Well, that drive certainly appears to have begun much earlier.

1892 – Julius Wolf (Economic Interdependence Theory & Gold Clearance Mechanism)49

Julius Wolf developed a structured financial clearing mechanism to manage international economic interdependence, aiming to streamline trade and reduce reliance on physical gold transfers. His work emerged in response to the increasing globalization of trade and finance in the late 19th century, setting the stage for structured economic governance.1899 – Eduard Bernstein (Revisionist Socialism)50

Observing the stability of capitalist economies amid growing financial interdependence, Bernstein rejected Marx’s theory of inevitable collapse and instead proposed a model of evolutionary socialism. His revisionist approach acknowledged the role of economic structures like Wolf’s clearing mechanism in stabilizing markets, advocating for democratic reform rather than revolution.1899 – First Hague Peace Conference (International Arbitration)51

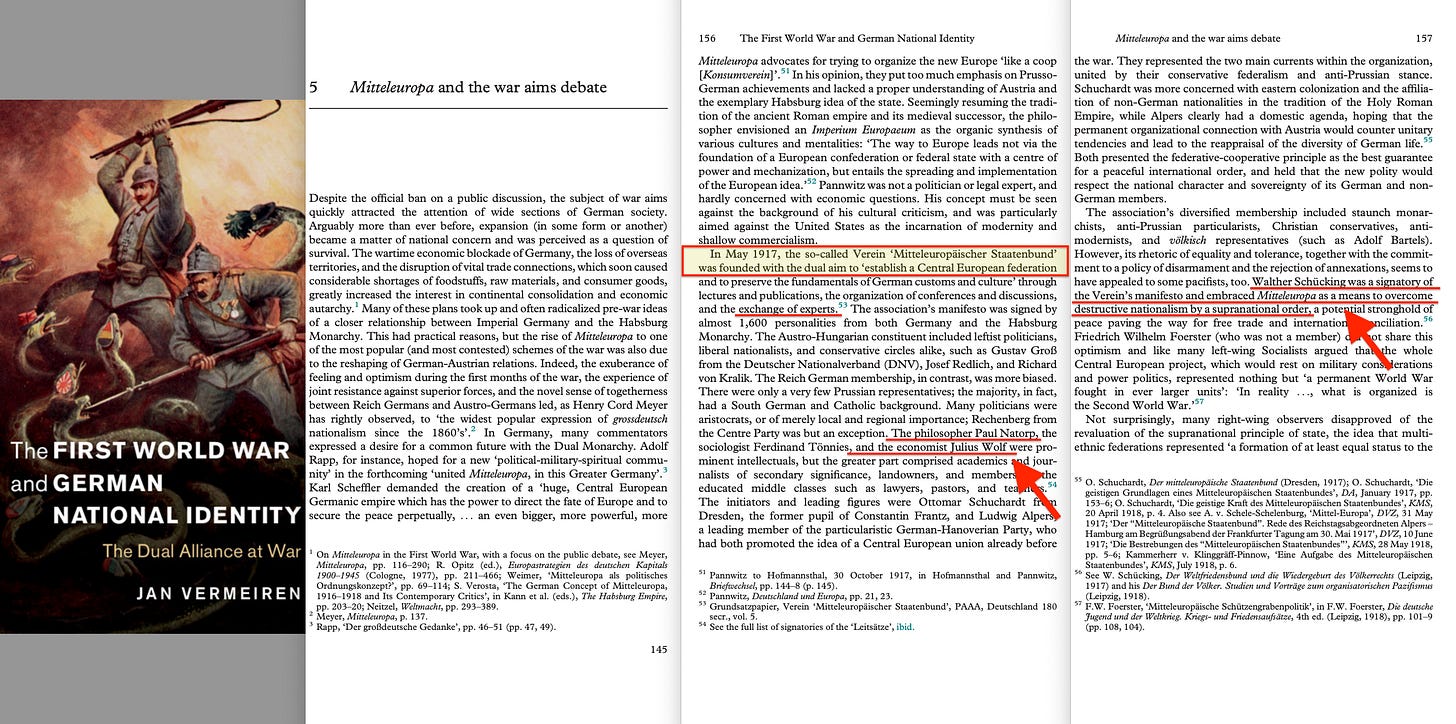

As financial and economic systems like Wolf’s clearing mechanism grew more structured, nations recognized the need for parallel legal mechanisms to prevent conflicts. The Hague Conference sought to institutionalize arbitration as a means of resolving international disputes, providing a legal foundation to support emerging economic governance structures.1904 – Mitteleuropäischer Wirtschaftsverein (Economic Integration)52

Expanding on Wolf’s economic interdependence theory, this initiative aimed to create a Central European economic bloc, ensuring stability and cooperation among nations. It followed the Hague Conference’s model of structured agreements by applying similar principles to trade and economic relations, further integrating the region.1907 – Second Hague Peace Conference (Expanding Arbitration)53

Building on the first Hague Conference, which established international arbitration, this second meeting refined enforcement mechanisms and expanded legal structures. As regional economic integration efforts like Mitteleuropa took shape, stronger legal frameworks were needed to manage disputes, reinforcing the alignment between economic governance and legal arbitration.1908 – Die Organisation der Welt (Schücking, Global Legal Structure)54

Walther Schücking expanded on the Second Hague Peace Conference’s legal frameworks, proposing a more formalized global legal structure to regulate international relations. As economic governance mechanisms like Mitteleuropa were developing in parallel, Schücking sought to integrate legal arbitration with broader institutional frameworks to ensure a structured approach to global governance.1916 – International Government (Woolf, Supranational Governance)55

Leonard Woolf built upon Bernstein’s revisionist socialism and the Hague arbitration framework, arguing that governance should extend beyond national borders to prevent conflicts and economic crises. With growing regional economic cooperation like Mitteleuropa and evolving legal structures from Schücking, Woolf’s model proposed an institutional framework for supranational political governance, foreshadowing later international organizations.1919 – Treaty of Versailles (Postwar Political & Economic Governance)56

The Treaty of Versailles was directly shaped by the arbitration mechanisms of the Hague Conferences and the supranational governance ideas of Woolf. It sought to impose a structured economic and political framework to manage postwar stability, integrating arbitration principles with economic restructuring in response to the failures of purely diplomatic conflict resolution.1919 – League of Nations (First Global Governance Structure)57

As an institutional response to the failures of the Hague Conference’s arbitration mechanisms to prevent war, the League of Nations incorporated Woolf’s supranational governance ideas. With the Treaty of Versailles providing an economic and political foundation, the League formalized global governance as a permanent structure rather than an ad hoc diplomatic process.1919 – International Research Council (Global Science Collaboration)58

Following the establishment of the League of Nations, scientific collaboration was seen as a crucial component of global governance. Inspired by the Hague Conferences’ arbitration mechanisms, the council was formed to standardize and coordinate international scientific efforts, aligning with the emerging governance structures.1923 – Coudenhove-Kalergi’s Pan-European Movement59

Coudenhove-Kalergi built on Mitteleuropa’s model of economic integration but expanded it into a broader political vision for a unified Europe. As the League of Nations attempted to establish global governance, this movement applied similar principles at the continental level, merging economic, political, and legal governance into a unified framework for Europe.1924 – Dawes Plan (Reparations Restructuring)60

The economic instability caused by the Treaty of Versailles led to a need for structured financial governance, building on Wolf’s clearing mechanisms and Mitteleuropa’s economic integration ideas. The Dawes Plan introduced financial restructuring within an international governance context, using League of Nations oversight to manage reparations and stabilize global financial relations61.

1929 – Young Plan (Final Reparations Agreement)62

Expanding on the Dawes Plan’s structured financial approach, the Young Plan refined international economic governance by introducing long-term financial stabilization strategies. As the League of Nations solidified its role in global governance, this plan integrated economic restructuring within the broader framework of arbitration and institutional oversight.1930 – Bank for International Settlements (BIS, First Global Financial Institution)63

The BIS was created as a direct continuation of Wolf’s clearing mechanism and the economic governance principles established in the Dawes and Young Plans. With financial restructuring becoming a key pillar of global governance, BIS institutionalized these mechanisms into a formal banking system under the oversight of international governance structures.1931 – International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU)64

Building on the International Research Council’s efforts, ICSU formalized scientific governance as a global initiative. As the League of Nations extended governance across political and economic spheres, ICSU sought to standardize scientific collaboration, ensuring that governance structures were informed by scientific research and technological progress.1939 – Bruce Committee (League of Nations Reform & Global Governance Evolution)65

As the League of Nations struggled with its lack of enforcement power, the Bruce Committee reviewed its failures and proposed a more structured governance model. It acknowledged the limitations of Hague-based arbitration and economic mechanisms like BIS, calling for a stronger institutional approach. Though its recommendations were overshadowed by World War II, they influenced the transition from the League to the United Nations.1941 – Atlantic Charter (Principles for Postwar Global Governance)66

The Atlantic Charter was a direct response to the failures of the League of Nations, outlining principles for a restructured global order. Drawing from the Treaty of Versailles’ economic governance framework and the League’s arbitration mechanisms, it emphasized self-determination, economic cooperation, and security coordination. Its vision influenced later institutional frameworks like the United Nations and Bretton Woods.1944 – Bretton Woods Conference (Economic Governance & IMF/World Bank Creation)67

The economic instability caused by the Great Depression and war required a new financial order, drawing on the structured economic governance of BIS, the Dawes and Young Plans, and Wolf’s financial clearing mechanisms. Bretton Woods institutionalized these financial principles within a global framework, creating the IMF and World Bank to stabilize international trade, regulate currency exchange, and manage postwar economic recovery.1944 – Dumbarton Oaks Conference (Blueprint for the United Nations)68

Building on the Atlantic Charter’s principles, Dumbarton Oaks was a formal gathering to structure the successor to the League of Nations. The failures of Hague-based arbitration and the League’s lack of enforcement mechanisms led to the design of a stronger, more centralized governance system. Integrating lessons from supranational governance models and financial restructuring efforts, it laid the institutional groundwork for the United Nations.1945 – United Nations (Replacing the League of Nations)69

The League of Nations’ inability to prevent global conflict led to its restructuring into the United Nations, incorporating lessons from the Hague Conferences, Woolf’s supranational governance, and the Treaty of Versailles. The UN merged political, economic, and legal governance into a single framework, refining the League’s institutional weaknesses and reinforcing arbitration mechanisms.1946 – UNESCO & ICSU Integration (Scientific Governance under UN)70

Following the League’s transition into the UN, scientific governance became a key component of international cooperation. ICSU’s earlier work was integrated into UNESCO, ensuring that governance decisions were informed by scientific expertise, aligning with the UN’s broader goal of structuring global institutions.1948 – International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)71

As global governance structures expanded beyond political and economic realms, IUCN applied similar institutional principles to environmental governance. Building on UNESCO’s scientific coordination, it formalized environmental policy within international governance, extending the arbitration-based model of the Hague Conferences to ecological concerns.