Cybernetic Thomism - Part I

Many will tell you about top-down authoritarian control through monopolisation of finance, advanced artificial intelligence, transhumanism, digital twins, dubious global health concerns, and controlling the flow of information. But few — if any — will tell you how — and why — this will conceptually work, and how it will be implemented.

Explaing precisely that is the objective of this post.

In the most recent article on One World, we saw how scientific data, interpreted through a subjective perspective become ethics, a process mirroring not only Bogdanov’s Empiriomonism, but also Thomist Realism in context of scientific monism, which posits that knowledge is hierarchically organised by an external force, determinable through scientific inquiry. The primary difference between the two lies in the perspective; where Thomist Reality argues this is the divine order, Bogdanov instead considered it being the output of a ‘collectively-subjective’ interpretation. But the perspective is necessary, because otherwise you’d end up with competing interpretations of the underlying knowledge (scientific data), leading to dualing sets of morality — and that is no good when the objective is to establish a universal moral framework.

The application of a subjective perspective thus ensures that the interpretation — much like the underlying scientific data — is universal. But this process of translation also introduces a mechanism which can be slowly manipulated, leading to a gradually changing universal moral framework, thus working to establish a lever of control reminiscent of TH Huxley’s Romanes Lecture on Evolutionary Ethics from 18931. And this, essentially, is what Barbara Marx Hubbard’s Conscious Evolution is about, and it is this function which — as the claim goes — will take us to Teilhard’s much fabled Omega Point, albeit Teilhard suggests this travels through spirituality as opposed to scientific monism.

Thus, regardless of whether you opt for Bogdanov’s Empiriomonism or Thomist Realism — the underlying universal truths (scientific data) can be turned into an ethical imperative telling us what we should and should not do; a universal moral framework, which then through Bogdanov’s Proletkult can be subtly integrated as manipulative moral imprinting through arts, education, culture, and even religion, ultimately landing with legal codification — the ethical imperative, turned into laws. And that legislation is necessary, as it provides the enforcement mechanism required to — through Bogdanov’s Tektology — control the ‘human superorganism’.

What I — in short — detail is that Bogdanov’s framework… is completely coherent. Empiriomonism, Proletkult and Tektology go together, hand in hand in a unified whole. The former leads to a universal moral framework which in the human superorganism is imprinted through Proletkult, and enforced through the legislative framework, guiding Tektology. In short, what Bogdanov collectively detailed was a top-down authoritarian dictatorship. It’s just a little hard to realise, as it’s all draped in insanely manipulative framing, through and through.

But a question of major importance still goes begging an answer — how will this be achieved? And that’s why we now will direct our attention back to Tektology, which in a more contemporary context was developed through a line of thinkers, starting with Ludwig von Bertalanffy under the term General Systems Theory.

If there’s one topic which has been covered repeatedly on this substack it’s… well, actually that would be ethics, with global surveillance probably in second place. But systems theory has certainly seen its fair share of attention. But of the many articles in this regard, Kenneth Boulding’s Skeleton of Science is probably the best, as it articulates the mechanical, hierarchical structure which runs through it all.

It’s a complex topic, and one which has seen plenty of development over the years. And it’s worth quickly reciting some of these core developments, because it clarifies much important detail.

Ludwin von Bertalanffy’s ‘General Systems Theory’ outlines the basic principles, but in simplified brief — everything is a connected system, with connections to other systems. What this means is that you, through your network of friends and family, represent a node in a interconnected system. You are, in short, a node in a vast network topology.

Kenneth Boulding’s ‘Skeleton of Science’ structures this enormeous network in a hierarchy. Easiest to envision is probably through a corporate structure, where the employee will have a boss, who in turn also likely will have a boss. And this chain carries all the way up through the hierarchy until you arrive with the Chief Executive Officer — the final boss, so to speak.

CW Churchman’s ‘Systems Approach’ adds that it is not enough that the hierarchy exists, but rather, it should be aligned. And that takes place through the fusion of ethics into the system, ensuring ideological alignment.

Russell Ackoff's ‘Creating the Corporate Future’ goes a step further, by introducing that the idelogical alignment should ultimately be driven by through a common purpose.

Erich Jantsch's ‘Self-Organising Universe’ takes the next step, detailing a purpose internal to the hierarchical organisation itself — survival. And this further comprise system integrity, and the ability to absorb external impacts — resilience.

R. Edward Freeman's ‘Stakeholder Theory’ completes the lineup. In contemporary discussions, this launched the focus on the ‘Stakeholder Approach’. The objective to this is managing external relations, and ensuring the hierarchical organisation ultimately serves its external objectives and requirements.

And though admittedly simplified, this does capture the essence of development. Consequently, the main characteristics exhibited through these developments:

Hierarchically organised, though often integrating networked or decentralised structures for matters of less importance.

Clear lines of authority, where decisions through principles of subsidiarity typically are ‘decentralised to the lowest appropriate level’.

Ideological alignment around a common purpose, promoted through company training, processes, events and social gatherings.

An internal purpose typically focused on survival, resilience, and adaptive growth.

An external purpose directed by stakeholders, including boards and committees, balancing diverse interests and objectives.

There are further two primary types of systems:

Open Systems: These exchange material, information, or energy with their external environment. Inputs and outputs flow in and out of the system, meaning it is influenced by, and can influence, outside systems beyond our control.

Closed Systems: These do not exchange material, information, or energy with the external environment. The system is self-contained and isolated from outside influences. However, in reality, perfect closed systems are rare, as most systems interact with their environments to some extent.

And this model, tracing all the way back to Alexander Bogdanov’s Tektology, forms the foundation of Adaptive Management. However, since this only describes the structure of the model, we still need to understand the flows within to fully grasp Adaptive Management — and that’s where Wassily Leontief’s Input-Output (I/O) Analysis enters the stage.

While we could trace a similar line of progression in the development of I/O analysis, that serves less of a purpose here. The important part is simply to understand that I/O analysis monitors the flows of materials, information, and energy within the system itself. From this, we can progressively come to understand general flows and feedback loops within the full system.

Once we have an understanding of these feedback loops, we’re in a position to hypothetically manipulate these flows with the aim of controlling the hierarchical system itself — a concept commonly known as Cybernetics, which focuses on the regulation and self-correction of systems through feedback mechanisms.

But in order to gather monitoring data on the system, we need to implement systemic surveillance across the entire hierarchy. Thus, should we consider the entire world as an example of a closed system—where material, energy, and information are largely contained within—it necessitates global surveillance to track and manage these flows.

The concept of viewing the entire world as a single, unified system is commonly illustrated by the ‘Spaceship Earth’ metaphor, where the planet is seen as a self-contained, closed system with finite resources, requiring meticulous management. While this perspective is fundamentally flawed, let’s consider it on its own terms, as it offers insight into how the conceptual system is structured. It begins with the circulation of materials within this closed system, monitored through global surveillance. These flows are then analyzed and ultimately controlled using Input-Output (I/O) Analysis and Cybernetics. This process is commonly referred to as the ‘Circular Economy’—an approach designed to minimise waste and optimise resource use through continuous feedback loops and recycling mechanisms.

So when we couple our General Systems Theory model of ‘Spaceship Earth’ with Input-Output (I/O) Analysis of our global surveillance data, we gain complementary sets of information about the entire system: the model represents the structure, similar to the arteries in your body, while the flow reflects the movement of materials, information, or energy, akin to the blood circulating within those arteries. In this analogy, the goal is to manipulate the system through the cybernetic control of these flows, much like regulating blood flow to maintain the health and functionality of the body.

In the context of ‘Spaceship Earth’, the coupling of General Systems Theory and Input-Output (I/O) Analysis, through the requirement of global surveillance, allows us to understand the entire system — while enabling the ability to predict future outcomes. This concept is commonly known as a ‘Digital Twin’, where the EU’s DestinE2 project models the future of Spaceship Earth using systems theory, with global biodiversity and climate data serving as the input for global surveillance.

And yes—this is all very real. None of this is speculative. Contemporary technological capacity now enables global-scale Digital Twin simulations, with the ultimate objective of increasingly employing computerised adaptive management to control and maintain planetary health. The widespread focus on ‘resilience’ in contemporary discourse directly relates to the hypothetical self-management of closed systems.

What’s also very real is that, although Wassily Leontief is credited with the invention of Input-Output (I/O) Analysis, Alexander Bogdanov had already developed a precursor to this concept through his work on supply chain analysis—which, in essence, applied the same principles of tracking and managing systemic flows. And as detailed in the prior Substack post on Bogdanov, it’s entirely likely that Leontief encountered Bogdanov’s work on the subject before leaving the Soviet Union for Germany in 1925.

Consequently, every major component of Adaptive Management can ultimately be traced back to Alexander Bogdanov, who, as I like to remind, was a founding member of the Bolshevik faction alongside Lenin in 1903.

Bogdanov even developed a concept that could be seen as a precursor to ‘Spaceship Earth’, outlining a planetary model focused on the circulation of carbon dioxide—an early attempt to understand Earth as a self-regulating system.

This systemic perspective directly connects to ideas later introduced by Technocracy, Inc. in the 1930s, which advocated for the scientific and technical management of society. Their framework emphasised energy certificates—which can broadly be understood as a conceptual precursor to carbon-backed Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs)—alongside resource accounting and the efficient circulation of energy and materials on a continental scale.

We can also, in context of ‘Spaceship Earth’ integrate a few further concepts:

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) represent an externally imposed purpose, aligning with Freeman’s Stakeholder Theory within the General Systems Theory timeline.

Global Ethics, derived through the normative lens of Thomist Realism and set within a worldview of scientific monism (i.e., Bogdanov’s Empiriomonism), connects to Churchman’s Systems Analysis, integrating ethics into the systems framework. These global ethics are further fused into morality through education, arts, religion, and culture before being codified into legislation.

One Health, grounded in systems theory, focuses on the pragmatic global management of biological resources, including humans, animals, and ecosystems.

The Ecosystem Approach, a systems theory concept, relates to the empirical global management of land and natural resources, emphasising measurable feedback loops and data-driven decision-making.

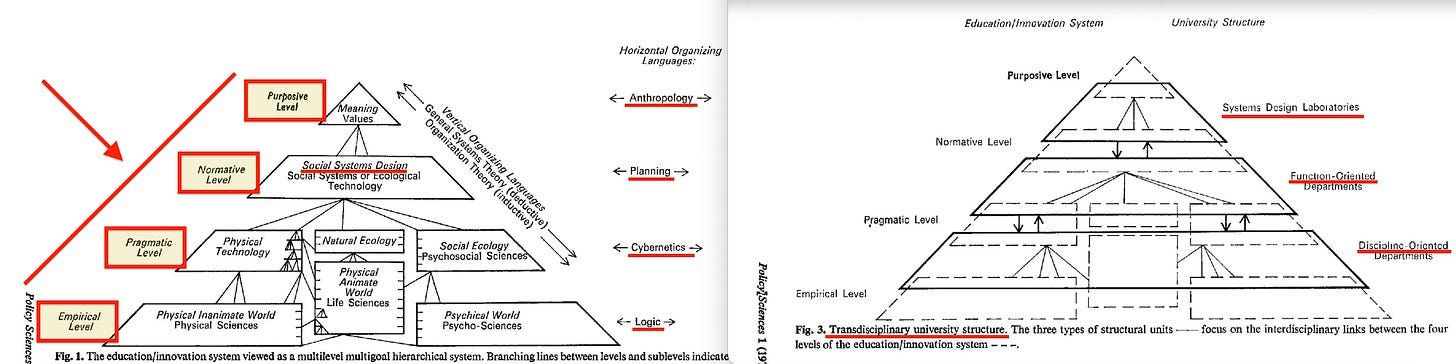

The ordering above also matches Erich Jantsch’s pivotal 1970 paper, which I have referenced on numerous occasions, on the ‘Inter- and Transdisciplinary University Structure’ which—in brief—is a systems theory adaptation of the Great Chain of Being.

This ordering further aligns with Erich Jantsch’s pivotal 1970 paper on the Inter- and Transdisciplinary University Structure3, which I have referenced on numerous occasions. In essence, Jantsch’s framework is a systems theory adaptation of the Great Chain of Being, structured across four hierarchical levels: purposive, normative, pragmatic, and empirical. Each level serves a distinct function in guiding and managing complex systems—from defining overarching global purposes like the SDGs, to embedding global ethics as normative values, implementing pragmatic solutions like One Health, and grounding these efforts in empirical management through approaches like ecosystem monitoring.

And within Jantsch’s structure, Systems Design Laboratories correspond to Bogdanov’s Empiriomonism, focusing on the synthesis of scientific data and subjective interpretation to create universal frameworks. The Function-Oriented Departments align with Bogdanov’s Proletkult, serving as the mechanism for cultural and societal imprinting through arts, education, and ideology. Finally, the Discipline-Oriented Departments reflect Bogdanov’s Tektology, focusing on the scientific organisation and control of systems, providing the structural backbone for managing the human superorganism.

It’s all exceedingly clever, and all of this leads to Bogdanov’s concept of the Integral Man, situated within his conceptual precursor to Spaceship Earth. This planetary model, with its emphasis on systemic circulation and resource management, aligns closely with the principles later advanced by Technocracy Inc.

Furthermore, if we reinterpret Zev Naveh’s Total Human Ecosystem as the Total-Human Ecosystem, it becomes evident how this framework could evolve into the notion of the Human Superorganism—a unified, managed entity where human, ecological, and technological systems are seamlessly integrated under a singular organisational logic.

And finally, this revolution in data, methods, technology, and the ‘holistic’ integration of science ties directly to the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’. The path to this runs through the ‘Great Reset’, which, in essence, reflects ‘The Great Transition’—first detailed in 1986 by Alexander King of the Club of Rome4. And this transition — in my book, at least — marks a shift toward Scientific Socialism, offering context for why Klaus Schwab prominently displays a statue of Lenin on his bookshelf.

The wholesale cybernetic manipulation of Spaceship Earth feedback loops thus operate through global surveillance and digital twins. However, this cybernetic control requires justification for us mere mortals—that’s where Empiriomonism comes into play. It translates cybernetic modifications into predicted digital twin outcomes, and this translation, viewed through Thomist Realism in a Scientific Monistic lens, becomes Global Ethics. And it is these ethics, channeled through Proletkult and Tektology, which are embedded into legislation, culture, education, and the arts. Consequently, this entire framework can be distilled into a single concept:

Cybernetic Thomism.

And — excitingly — this is now recognised as a new and emerging field.

And that will be the topic of part 2.