Our Common Future

October 19, 1987—Black Monday—was the biggest one-day stock market crash in modern financial history. The Dow Jones dropped 22.6% in a single day, signalling a global financial system shock, which wasn’t limited to the United States, as markets in London, Hong Kong, and Europe followed suit.

This event served as a catalyst, synthesising the global financial architecture with Brundtland’s call for sustainable development and—global governance.

Market volatility is a powerful tool should you seek to bury information. In 1929, for instance, the markets crashed exactly as they negotiated the Bank for International Settlements. During market turmoil in 2001, a vastly underreported declaration was signed, and in 2009, a similarly underreported project launched, deserving of far more attention than it received. And though what took place in 2020 hardly needs mentioning, the financial engineering it required to support is a chapter in itself.

The official version typically states that Black Monday—at least in part—was triggered by early algorithmic trading1—programmed portfolio insurance strategies that dumped stocks as they fell, thus accelerating the crash. It was the outcome of a financial system increasingly dominated by complex, yet fragile financial instruments, while global integration ensured it quickly materialised overseas.

But what’s significant about Black Monday is the response. The newly appointed Fed chairman Alan Greenspan2 issued a now-famous statement promising liquidity to the financial system. A decisive call—the beginning of an era in which central banks would actively intervene during crises, setting the precedent for what would later become ‘too big to fail’3. But by logical extension, this would also allow them to pick winners and losers.

Black Monday further led to a tightening of the global financial architecture. It forced coordination—thus, centralisation—between central banks, helping to consolidate the shift toward a globalised financial regime. If anything, it served as a test run for supranational crisis management—justified through the logic of systemic fragility. And today, the Bank for International Settlements is responsible for not only central bank cooperation, but through the Basel Framework4 also for system stability5 and to an increasing extent—oversight.

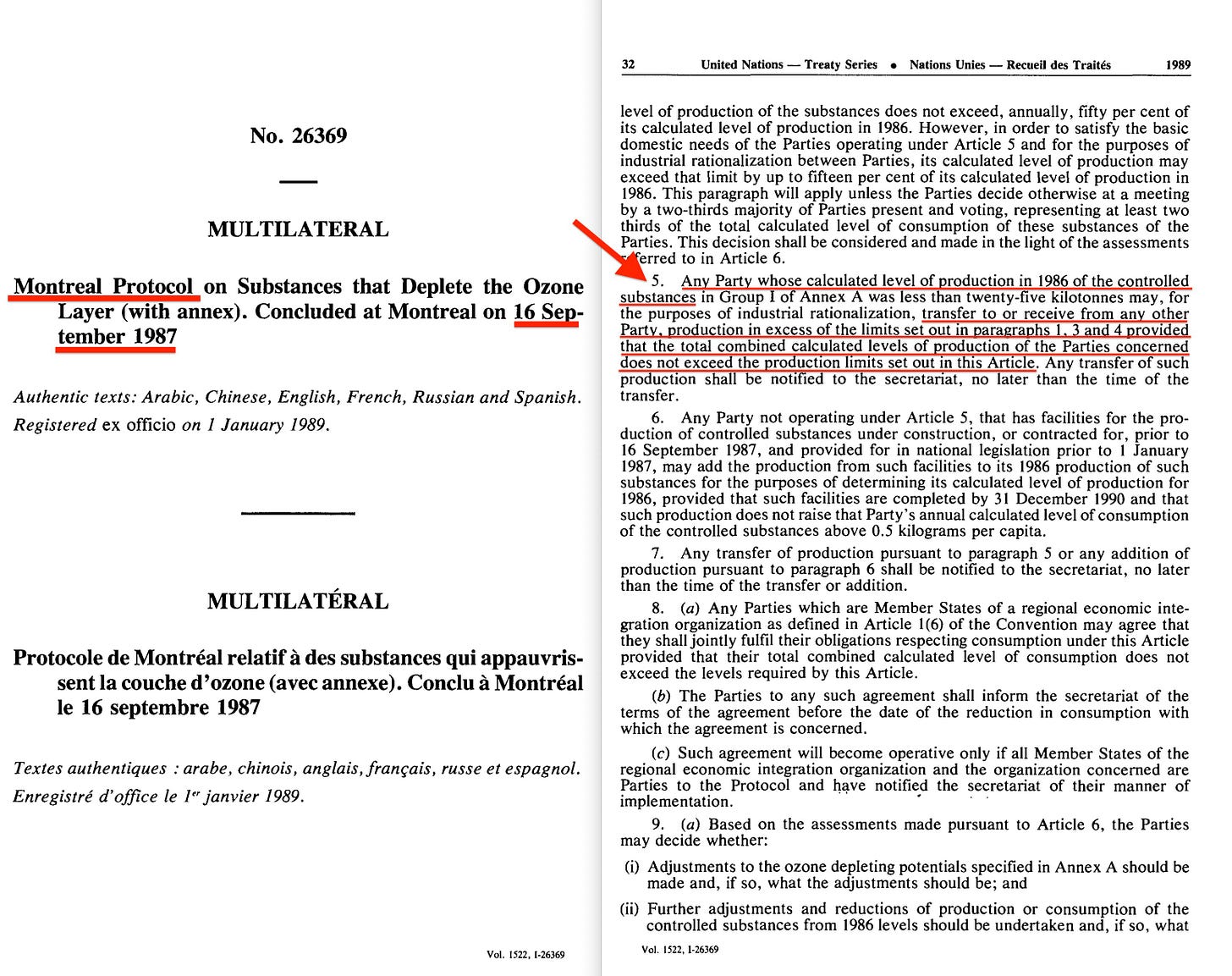

And all of this happened, notably, a mere weeks after the Brundtland Commission6 released Our Common Future. And that same year further saw the Montreal Protocol7 signed, which allowed for the transfer of emission permits.

While the crash was financial on the surface, it was also symbolic: another jolt to justify the consolidation of global management structures. As in 1929, 2001, 2009, and 2020, crisis wasn’t the exception—it was the accelerant, enabling crisis economics.

So—simply put—in one fell swoop back in 1987, Black Monday delegitimised free markets8—only weeks after Our Common Future (and thus the concept of sustainable development) came to be in official capacity. It put central banks in the position of protecting large banks at will, gradually reconciled market economics with social cohesion, redefined the role of the state as a facilitator rather than a controller9, and—when considered together with Brundtland’s report—subtly launched the governance-through-networks logic in the domain of finance that Reinicke would later formalise through Trisectoral Networks in 2000.

All while the Montreal Protocol created the transferable emission permit, which would, through the intermediate IPCC Working Group III in 199010, become the 1992 system of monetisation launched through Combating Global Warming, as the Convention on Biological Diversity and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change treaties came to be at the Rio Earth Summit.

Meanwhile, Agenda 2111 subversively outlined the future of global governance through General Consultative Status NGO-controlled societal ‘common goods’.

But what also took place in 1987 was the critically underreported Fourth World Wilderness Congress, where the World Conservation Bank was first suggested. That initiative, in turn, became the Global Environment Facility, which provided the financial mechanism enabling both the UNFCCC and the CBD. And those, in effect, focus on different sides of the carbon equation—where the former focuses on carbon emissions, the latter relates to carbon sequestration. And both of those types are currently being used for carbon-backed CBDCs.

Consequently, if you zoom out and take an even wider view, the role of Black Monday, the Brundtland Report, and the Earth Summit—when taken together—led to a monetiseable stronghold on carbon emissions and sequestration, with both set to be used to back particular types of Central Bank Digital Currencies, all while Black Monday led to the progressive curtailment of economic liberty, gradually being redirecting under the claimed aspiration of serving ‘the common good’—as defined by non-government organisations—ultimately leading back to Eduard Bernstein and Leonard S. Woolf. And that ‘common good’, by and large, relate to the same environmental focus launched by Brundtland in 1987, with even central banks now cooperating on Net Zero through Network for Greening the Financial System12.

And it’s a clever scheme, really is. Because while Julius Wolf’s original gold clearing mechanism from 1892, used by the BIS during its founding, focused squarely on gold, the central banks have essentially moved the focus of that same balancing mechanism from a rare metal—easily quantifiable—and onto particles, continuously circulating naturally through various media, including the world’s oceans.

But while some of this may appear speculative, a 2023 Fabian Society report made the next objective in their scheme fairly clear. In Tandem, without ambiguity, calls for the creation of an Economic Policy Coordination Committee—comprising the Treasury, the Bank of England, and selected NGOs—positioned outside democratic accountability, with the objective of directing fiscal policy. Consequently, the stakeholder mediation principle outlined through, not least, Agenda 21 would soon come to impact taxation and spending policy—largely outside of democratic reach.

Only a week ago, Manfred Bienefeld issued a very similar call—strongly echoing that of Eduard Bernstein—proposing a strategy of curtailing financial liberty in favour of public-private partnerships for the common good, where that common good in context of sustainable development and planetary stewardship, would be directed by the likes of the IUCN or similar connected organisations or their member bodies—entirely outside democratic capacity—yet expressly aligned with In Tandem’s recommendation of the EPCC. It is, in no uncertain terms, an attempt to seize power under epic quantities of manipulative Aesopian terminology.

Incidentally, Bienefeld also happens to be a member of the Centre on Values and Ethics13—though this, naturally, is par for the course in this context. Because the ethics reflects the imperative to act. It’s a subjective version of the allegedly objective best available scientific consensus.

Brundtland’s Our Common Future14 is yet another document I’ve intentionally steered clear of. See, it's another wishy-washy soft law document chock full of aspirational, feelgood rhetoric, but which offers very little clarity on what it actually sets out to do. This same pattern recurs throughout the United Nations system, with Agenda 21 serving as a particularly… confusing, yet relevant example.

Sure, Our Common Future reframes the global policy agenda around sustainable development, and it lays the groundwork for trisectoral governance — but with the United Nations in the role of the central mediator. It also sets the stage for environmental crisis-driven legitimacy, which in short relies upon crisis economics. And it further includes mention of the global ethic, quietly launched in environmental context through IUCN’s Caring for the Earth in 1991, finally to be directly called for through the Earth Charter, finalised in the year 2000.

So we have sustainable development, global ethics, and crisis economics. But that still falls short of the report’s most central objective, which—much as the case was with the global governance model floated through Agenda 21—is merely quietly whispered. While it never names it explicitly, the logic is unmistakable: interdependence, feedback loops, thresholds, integrated management, and the collapse of boundaries between ecology, economy, and society.

Our Common Future reframes the world as a system. It introduces systems thinking into global policy discourse, subtly shifting how problems and solutions are conceptualised on Spaceship Earth. As a result, the report laid the groundwork for the systems theory that we later saw developed through:

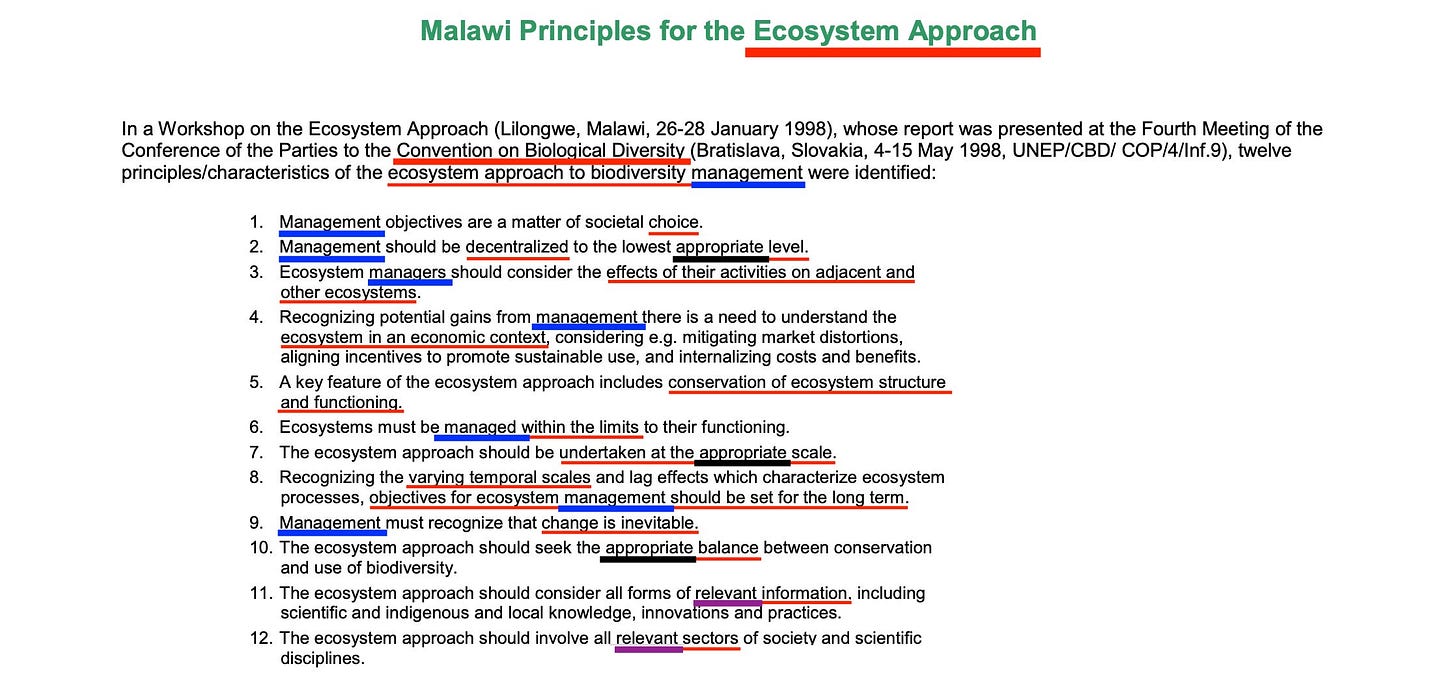

The Convention on Biological Diversity’s Ecosystem Approach (management of the geosphere: land and resources), formalised in 1997.

One Health (management of the biosphere: life and zoonotic interfaces), initiated in Hong Kong in 1997 in response to the alleged H5N1 avian influenza outbreak, formally articulated through the 12 Manhattan Principles in 2004, and later expanded into the Berlin Principles in 2019—broadening its scope to include climate change, biodiversity loss, antimicrobial resistance, and systems-level risk governance.

A Global Ethic (management of the noosphere: collective conscience), first introduced at the Parliament of the World’s Religions in 1993, then expanded with a planetary focus through the Earth Charter in 2000, laying the foundation for a Planetary Ethic.

The Sustainable Development Goals (setting the overarching telos of governance), adopted by the UN in 2015.

But there’s more, because these also encapsulate:

Planetary Health serves as the practical and moral objective of this synthesis—a holistic outcome of managing the geosphere, biosphere, and noosphere in coordinated unison, aligning scientific management with moral purpose.

Zev Naveh’s Total Human Ecosystem provides the theoretical scaffold for this integration, treating land, life, and mind as interconnected components of a single, governable system.

Spaceship Earth remains the overriding metaphor: a closed-system planetary vessel, dependent on holistic management, coordinated inputs, and continuous adjustment—by those deemed capable of adaptively steering its course.

The Circular Economy extends closed-system logic to materials through Input-Output Analysis of critical resources. It demands global resource tracking, real-time monitoring, and Digital Twin modelling of planetary-scale flows—flows typically derived from or integrated with the Global Earth Observation System of Systems (GEOSS) and its associated data infrastructures.

Circular Health, in turn, applies this input-output framework to the domain of health—mapping and managing wellness, disease, and biopolitical risk across every subsystem of Spaceship Earth. It represents the surveillance, modelling, and predictive analytics layer of One Health, converting ecological and epidemiological data into real-time governance tools. This logic finds expression in global public health surveillance systems—visibly normalised in 2020 during the alleged pandemic, but rooted much earlier: first through the Global Environment Monitoring System (GEMS) launched in 1974, and significantly expanded under the Clinton-Gore administration in 1996, which championed health-environment integration and data-driven bio-monitoring

The overall objective—the telos—is the management of Spaceship Earth through Sustainable Development, based upon systems theory. Yet while it’s commonly claimed that Our Common Future gave birth to the concept of sustainable development itself, that’s not quite accurate. The International Foundation for Development Alternatives (IFDA) had already contextualised the term in 197915, and the IUCN’s World Conservation Strategy16 from 1980 featured it prominently—even included the phrase on its front page. One could go further still: Barbara Ward, an early promoter of the Spaceship Earth metaphor, had been articulating similar ideas well before Brundtland. As early as 1976, she proposed a Global Compact17 for economic development between the Global North and South—anticipating many of the themes that would later be codified under the SDG framework.

And with sustainable development defined as the ingration of environmental, economic and social aspects of society, the next objective was the specifics—purposive goals, paired with normative global ethics, pragmatic organisation of life systems, and empirical observation of resources and biospheric dynamics—with this paradigm further aligning with Erich Jantsch’s 1970 paper on the Inter- and Transdisciplinary University Structures18, which essentially outline a systems theory adaptation of the Great Chain of Being.

And while I don’t intend to conduct a full-scale analysis of Our Common Future, one key detail is worth underscoring: the word ‘system’ appears an impressive 340 times across the 400-page document—a text composed largely of repetitive, soft-prescriptive language. This is a frequency rarely observed in similar reports, typically only found in technical Systems Theory or Engineering texts. It is, in short, an exceedingly high ratio for such a document.

In terms of specific instances, ‘ecosystem’ appears 86 times, ‘economic system’ 12 times, ‘planetary system’ 5 times, ‘natural system’ 12 times, and ‘UN system’ another 18 times. Simply put, you won’t read Brundtland’s finest for long without some kind of system appearing in the text, regardless of the page you read from. And the type of system is versatile, including a wide variety of different systems.

Other terms of interest stand out as well. The Global Environment Monitoring System is explicitly referenced—pointing toward a planetary surveillance architecture. The Montreal Protocol receives indirect mention, as does the call to fuse economy and ecology—a fusion that would later materialise through proposals like carbon-backed central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). The document also advocates for adaptive systems (though it never names them as such) and openly acknowledges the scale of the Latin American debt crisis.

But its treatment of the crisis appears somewhat selective: Latin American debt began building in the 1960s, with the final blow arguably struck in 1971, when Nixon closed the gold window and floated the dollar—effectively destabilising many South American economies. This does not quite match the version outlined in the report, and the rampant inflation of the 1970s further goes unmentioned, instead suggesting that monetary policies were too tight, which—given inflationary pressures at the time—appears somewhat odd. Then again, Our Common Future reads less like sober policy analysis and more like a political sales pitch to centre-left governments—not traditionally known for their grave concerns with fiscal restraint, nor historical accuracy of macroeconomic policy.

The topic of economics is covered in chapter 3, and beyond calls for restructuring debts, more lending, debt forgiveness, and longer-term rescheduling, the report also identifies technology transfers for the developing nations, while the developed nations must make their consumption and production patterns sustainable in the context of higher global growth. And that is a telling inclusion, because a national government, of course, will struggle to facilitate this—but the international organisation highlighted by Leonard S Woolf in 1916… will not.

But there are a few telling inclusions in terms of how these people think:

International cooperation to achieve the former is embrvonic. and to achieve the latter, negligible. In practice, and in the absence of global management of the economy or the environment, attention must be focuses on the improvement of policies in areas where the scope for cooperation is already defined: aid, trade, transnational corporations and technology transfer.

No, at the time there was no global management of either the economy or the environment—and some might actually prefer it that way. But the report highlights the international organisations as a way to circumvent most of these lacks. Beyond this, in terms of increasing the flow of finance:

Two interrelated concerns lie at the heart of our recommendations on financial flows: one concerns the quantity, the other the 'quality of resource flows to developing countries. The need for more resources cannot be evaded. The idea that developing countries would do better to live within their limited means is a cruel illusion. Global poverty cannot be reduced by the governments of poor countries acting alone. At the same time, more aid and other forms of finance, while necessary, are not sufficient. Projects and programmes must be designed for sustainable development.

There could be a number of ways to eliminate this problem, but the large banks obviously cannot accept taking haircuts (the taxpayer must bail them out in full). But living within their means, similarly, is not an option. Yet the funds provided are quite simply insufficient, and this increased flow must go towards sustainable development, such as… the restoration of biodiversity, climate change projects, and expressly the sort of watershed protection project which the Clinton administration in 1993 used when they searched for a solution to the non-issue of the Northern Spotted Owl, which—logically, through Al Gore’s task force—led to… the very first detailed outline of the Ecosystem Approach.

Naturally, the Bretton Woods institutions must be involved in this regard… and in 1992, the World Bank requested civil service reform in third world nations or development aid would be cut off (with UNDP in 1997 requesting electoral reform). And developing nations must further cooperate in organisations… suspiciously named similarly to the CGIAR.

Finally, the sustainable world economy calls for aversion of catastrophes in the spheres of economic, social and environmental spheres, naturally facilitated through neoliberal trade policies, which—per Woolf—in effect work to synchronose cross-border policies out of necessity. An inclusion of concessional finance further is telling, as this expressly is what blended finance preys on. And an emphasis on ‘new dimensions of multilateralism are essential to human progress’, which could easily be understood as the inclusion of CSO partners, working to define the ‘common good’ in public-private-partnership arrangements.

The report also places an outsized emphasis on renewable energy—but even more so on energy efficiency. In fact, the latter is presented as the preferred path forward, which suggests a degree of influence on contemporary policy trajectories.

Our Common Future, thus, called for a substantial change to the financial system as it existed in 1987—one which works to serve ulterior objectives, but merely as a conduit for financial transactions—such as protection from environmental and social harm. And that systemic shock took place on October 19, 1987, as markets crashed against a backdrop of S&L corruption—not forgetting the theatre release of Wall Street19 in December of that year, starring Michael Douglas in the role of Gordon Gekko, an unscrupulous Wall Street ‘whale’ willing to entertain any level of corruption provided it nets him a dime—not forgetting Gekko’s related memorable line: ‘greed is good’.

Everyone—and their dog—was continuously reminded exactly how greedy those Wall Street bankers were, and why that was morally unjustifiable. And it’s hard, of course, to take the opposite side of that argument, as it did happen again during the dot-com days of 200020… and the collapse and ensuing scandal of Enron in 200121… and the subprime lending crash of 2008–0922. Greed was—most certainly—not good, yet the Enron bankruptcy incredibly had the solution to the problem handy.

See, in hindsight it was decided that Enron was a failure of business ethics. On the surface of things, this appears somewhat odd—not only because Enron certainly broke a whole range of laws, thus rendering any focus on ethics irrelevant—but further, as ethics is one of those terms which has traditionally been applied more for its ornamental aspects. But these were no ordinary days—because these were the days where business ethics were starting to pick up pace under different labels.

Consequently, the Black Monday crash of 1987 co-initiated a sequence of events that slowly reshaped the global order—and this was not merely a reactive sequence of crisis management, but the deliberate construction of a managerial global order. It redeployed the language of ‘the common good’, first articulated through revisionist Marxist Eduard Bernstein’s 1899 theory of social democracy. Initially envisioned by Julius Wolf in 1892 as a framework for national reconciliation between labour and capital (with the gold clearing mechanism eventually used by the BIS in 1930 neatly tucked in), this ideal was gradually abstracted and globalised—repurposed to legitimise a technocratic regime in which public authority is increasingly fused with corporate power and expert networks. Leonard S. Woolf’s International Government served as a critical intermediary, laying the blueprint for its institutional fusion into the League of Nations and, eventually, the United Nations.

The Third System of the 1970s built on this by focusing on the Civil Society Organisation as the mechanism for defining and executing the ‘common good’, with the IUCN serving as a particularly illustrative example in the domain of Planetary Stewardship. The Brundtland Report and the Rio Earth Summit accelerated this transformation, embedding sustainability as the moral pretext for supranational governance. Through Agenda 21, the UN system delegated operational authority to General Consultative Status NGOs, leading to a mechanism of governance-through-mediation. These NGOs—often transnational in nature—assumed responsibility for managing societal ‘common goods’ on behalf of the international community—consolidating executive powers without electoral legitimacy, but rather with the sort of institutional leverage expressly outlined by Leonard S Woolf back in 1916.

Parallel to this NGO-led framework, a suite of financial instruments began to institutionalise the economic logic of sustainability. Market mechanisms such as blended finance enabled the gradual monetisation of ‘ecosystem services’ provided by so-called ‘natural assets’. These were progressively embedded within UN policy following the post–Kofi Annan 1997 reforms, beginning with Wolfgang Reinicke’s Trisectoral Networks framework in 2000. Blended finance was effectively introduced through the Copenhagen Accord of 2009, and vastly accelerated via the Paris Agreement of 2015—promising untold billions in Western taxpayer funding for biodiversity and climate-related conservation. These flows would be promptly monetised by the billionaire class through Global Environment Facility–backed structures, cementing a new frontier in public-private extractive governance under the guise of planetary care.

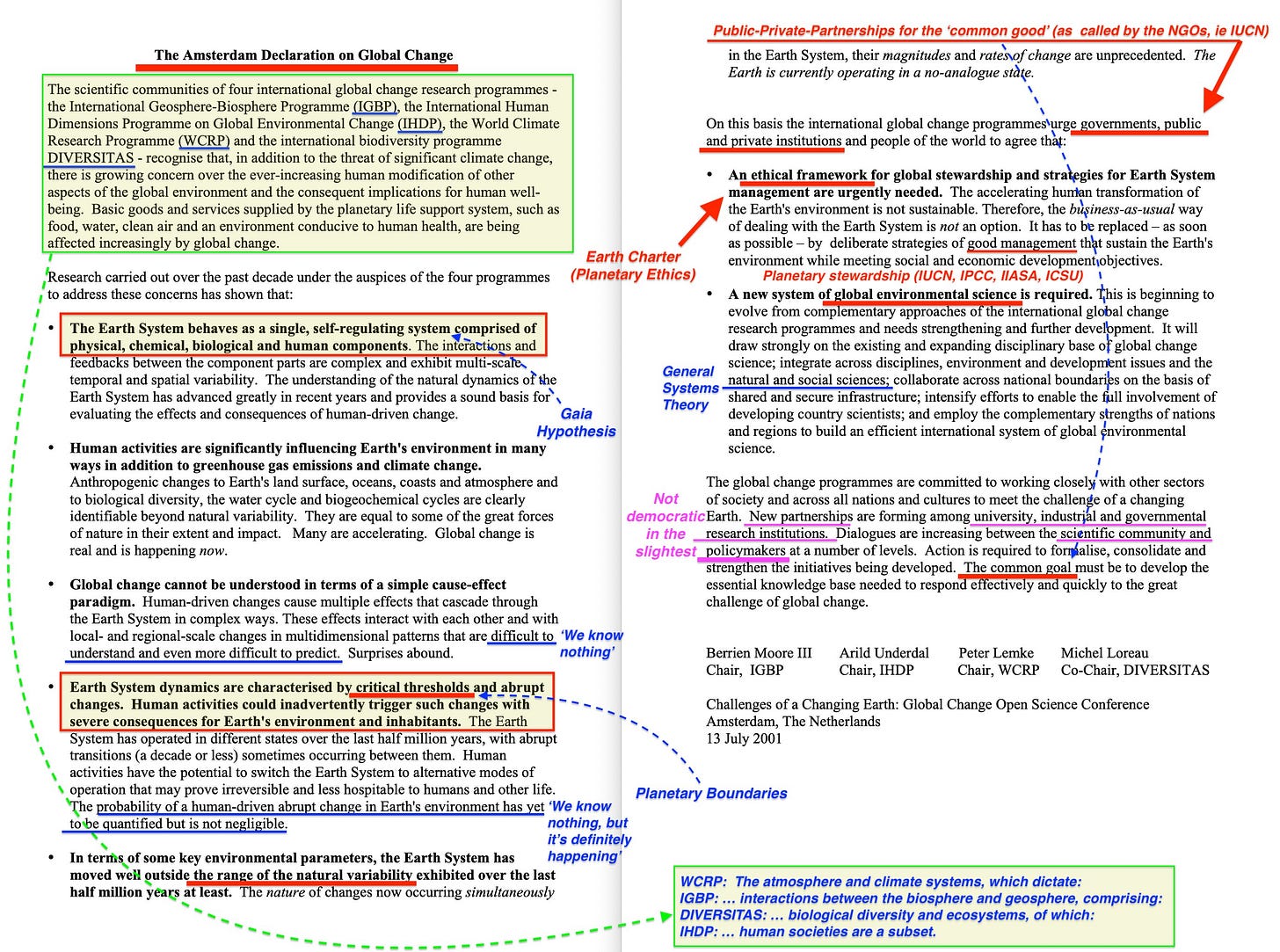

But this systems-oriented vision was finally formalised in 2001 through the Amsterdam Declaration on Global Change23, which declared humanity a ‘major force of planetary transformation’ and called for integrated Earth system science to underpin governance. It laid the intellectual foundation for the Earth System Governance Project, launched on a backdrop of crashing financial markets in 2009, which created a framework resting not on democratic principle, but systems engineering. Importantly, the 2001 Declaration emerged as a coordinated partnership involving four key international research programmes: the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP), the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP), DIVERSITAS (focused on biodiversity and ecosystems), and the International Human Dimensions Programme on Global Environmental Change (IHDP), which studied the behavioural and governance aspects of human-environment interaction.

And should it not already be clear, each of these programmes represents a tier within a larger systems hierarchy. The WCRP maps atmospheric and climate systems which influence the geophysical and biogeochemical planetary processes modelled by IGBP. DIVERSITAS then focuses on the state and governance of the biosphere, and IHDP frames human behaviour and institutions as a manageable subsystem within it all. Together, they comprise a layered architecture of Spaceship Earth—an ordered hierarchy of atmosphere, geosphere, biosphere, and humanity within, now to be managed via holistic, integrated systems science, and global coordination.

And by 2015, this global coordination had been provided a telos through the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—a masterplan that absorbed health, education, climate, and economics into a unified, metrics-driven logic of governance, monitored through indicators largely derived from normalised global surveillance infrastructure data such as GEOSS. But the goals introduced in 2015 are not the logical endpoint. Even as the SDGs were being adopted, some circles were beginning to include an 18th goal24, even consider a post-2030 agenda—thus working to frame these goals as a transitional staging post in a longer arc toward permanent, adaptive planetary management. Indeed, this trajectory is embedded within the SDGs themselves, which may be understood as an evolution of the Millennium Development Goals25 first published in 2000. Consequently, it may not be a stretch to suggest that the SDGs—framed in Teilhardian terms—might well be intended to chart a course toward the Omega Point.

But the deeper roots of this paradigm include other less-known milestones. Beyond the ideological lineage of Julius Wolf, Eduard Bernstein, and Leonard S. Woolf, the year 1984 also witnessed the emergence of An Interfaith Declaration: A Code of Ethics on International Business for Christians, Muslims and Jews26—an effort that, by 1988, included direct collaboration with Evelyn de Rothschild27. Its aim was unmistakable: to align global commerce with a universal moral narrative.

This initiative helped seed the Global Ethic discourse, later championed by Hans Küng and ultimately channelled into the framework of Planetary Ethics via the Earth Charter of 2000, after which the Enron collapse drove an unnecessary call for business ethics, gradually integrated within CSR and ESG values.

All of this served, in effect, as the cultural lubricant for stakeholder capitalism—paving the way for the 2014 Council for Inclusive Capitalism, an event that brought the Vatican28 and the Rothschild dynasty29 into explicit alignment. By 2017, the Vatican had partnered with Jeffrey Sachs to produce Ethics in Action for Sustainable Development—one of the most controversial and revealing documents I have ever read.

And as for Jeffrey Sachs, it bears recalling: he was among the first cosignatories of the 2009 revision of Hans Küng’s Global Economic Ethic, tailored specifically for business.

Together, these trajectories—ethical, financial, and quasi-scientific—have converged into an integrated system that now governs not only global economic flows through the control of carbon (CBD, UNFCCC), but further food (UNFAO), water (GEMS/Water), and health (Planetary Health, One Health, WHO Pandemic Treaty). In the name of resilience and sustainability, the world has been reframed as a closed-loop system of interdependence, and thus interlocking risks—requiring continuous global surveillance for real-time input-output analysis via GEOSS-derived platforms, moral guidance channeled through education and culture, and technocratic intervention to maintain planetary equilibrium.

All, of course, in service of the common good.

And all of this rests on stakeholder governance—more accurately described as undemocratic mediation—with the entire world gradually placed within a formalised hierarchy. The principle of subsidiarity is often invoked to justify this structure, claiming to ‘decentralise decisions to the lowest appropriate level’, a phrase which should further be familiar to those well versed with Ecosystem Approach principle 230.

But what few discuss—or are even aware of—is how the stakeholder selection process works. It is, in short, a complete mockery of any kind of democratic principle.

As for subsidiarity—the devil, as always, is in the detail: the Sustainable Development Goals become not merely global aims, but binding mandates. Subsidiarity thus becomes a managed illusion—local autonomy in service of global objectives, upheld by global institutions—where local authorities can further be brought under control through performance targets and the threat of financial penalties. This technique is particularly effective in cash-strapped municipalities increasingly dependent on central government support. A strategy of squeezing local councils, then, seems not only plausible but likely—and this strategy, incidentally, was outlined by Tony Blair in his 1998 Fabian Society pamphlet which conveniently had gone almost completely missing—The Third Way.

And the prospect of collapsing council finances is very real today31, thus forcing these into a fiscal straitjacket—and hence more compliant—or else councillors will be met by locals, outraged about elderly care or local schools having their funding cut.

Incidentally, the subsidiarity model was quietly outlined by the 1978 Declaration of Alma-Ata32 and reinforced by the 1986 Ottawa Charter33, both of which set out to define the global health system through Primary Health Care34, later to be expanded into Universal Health Coverage35. In these frameworks, key functions—such as information, education, drug and vaccine procurement—were to be centralised under global authority, while other elements would be ‘decentralised to the lowest appropriate level’, such as the delivery of health services themselves. The one exception? Quarantine enforcement during pandemics—always reserved as a central prerogative, dynamically applicable at any level, at the drop of a hat. A foreshadowing, perhaps, of the post-2020 public health architecture, which saw entire regions locked down while others remained open—seemingly at random, and certainly not on the basis of any consistently applied or trustworthy scientific threshold.

The October 19, 1987 event of Black Monday, then, served as a catalyst—synchronising early applications of what would become Earth Systems Science with the emerging global financial architecture. It marked the convergence of crisis management, ecological discourse, and capital flows into a framework that would, with time, evolve into a model of global governance—obscured beneath a dense cloud of Aesopian language and moral pretext, certainly visible through its calls to protect women, minorities, and those of an alternate lifestyle. Of course, these very same actors will regularly attack, say, those of age for rejecting the EU during the Brexit referendum, conclusively proving that their alleged care is nothing short of phony, a mere manipulative tool of political expedience which will be used differently at the drop of a hat, conveniently as ‘the science changes’.

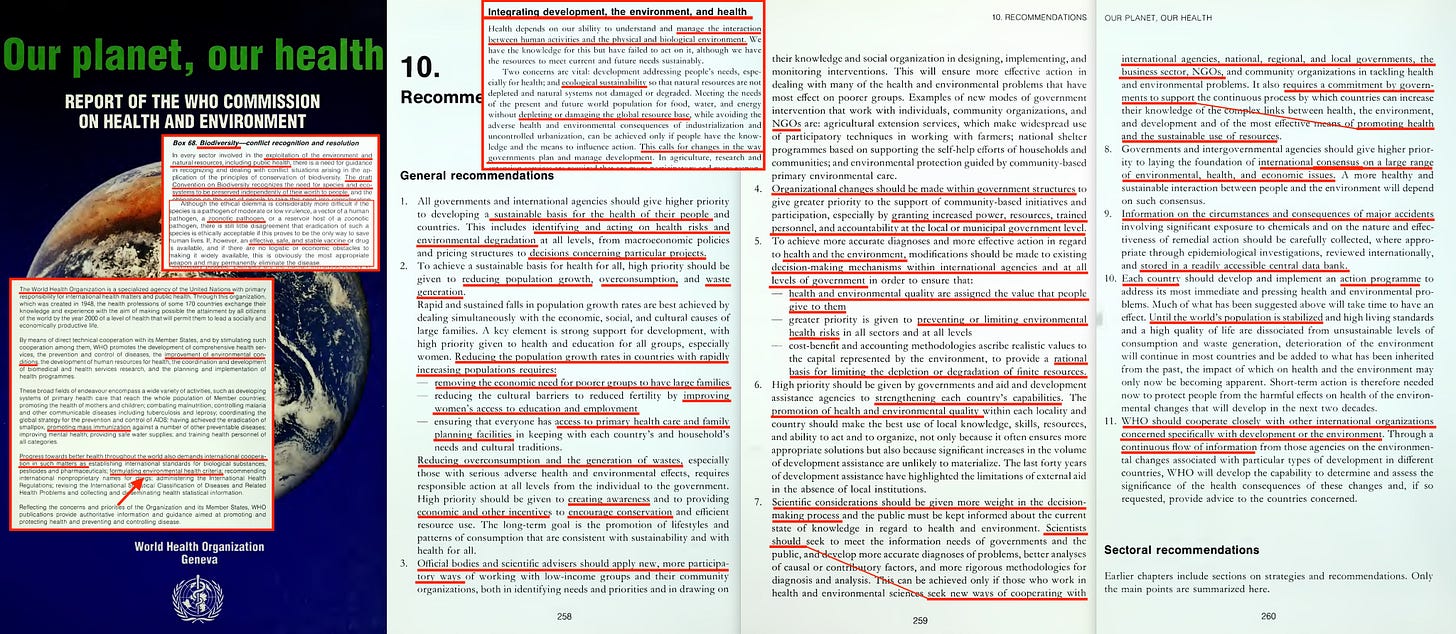

But we still have a vital component missing - the gradual synthesis of environmental and human health narratives, which unfolded through the lens of zoonotic illness, formally launched at the 1968 UNESCO Biosphere Conference and later accelerated by the World Health Organization’s Our Planet, Our Health report in 199236. That same year, virologist Joshua Lederberg spotlighted the alleged threat of emerging infectious diseases37—and, tellingly, the European Union began drafting related legislative frameworks38, mere months after Denmark rejected the Maastricht Treaty39, putting the entire experiment at risk.

Zoonotic illnesses were—for lack of a better word—the glue that integrated humanity into the One Health environmental framework—refined and formalised in the specialised context of pandemics under the Pandemic Treaty presently under negotiation. But that initiative began much earlier, with William Foege signing the 1978 US Pandemic Plan—the very same Foege who, at the Rockefeller Centre in 2004, would formally present the 12 Manhattan Principles (also known as One Health) to the world. A deserved spotlight must also fall on the 1999 WHO Influenza Pandemic Plan, which was, in essence, entirely drafted by the European Scientific Working Group on Influenza—a pharmaceutical lobby group that had questionably raised the alarm in 1997 over the highly implausible H5N1 outbreak in Hong Kong.

Consequently, I will do a second take of the above:

The October 19, 1987 event of Black Monday, then, served as a catalyst—synchronising early applications of what would become Earth Systems Science with the emerging global financial architecture, under a guise of morality gradually to be enforced through mandatory CSR and ESG compliance.

And this systems science would eventually come to comprise the atmosphere, geosphere, biosphere, noosphere… all under a telos of Planetary Health—ultimately through a Global Surveillance architecture enabling the Circular Economy, consequently leading to the Planetary Management of Spaceship Earth—and the entire Total Human Ecosystem within.

But 1987 is also remarkable for another reason: it was the year in which Mikhail Gorbachev delivered his speech To Feel Responsible for the World's Destiny—outlining a strategic pivot to defeat the West not through military confrontation, but through the removal of the Soviet threat narrative, to be replaced by a new unifying crisis:

The spectre of global environmental collapse.

And it’s at this stage that I will suggest that it almost begins to appear conspiratorial to suggest Gorbachev didn’t get his wish—especially as he, soon after the alleged collapse of the Soviet Union, co-founded Green Cross International40, emphasising environmentalism.

Finally, let’s run through a chronology of events, largely in order, but with some minor (intra-year) reordering to highlight outcomes logically:

Black Monday (1987) served as the systemic shock that marked the beginning of the long-term dismantling of economic liberty41 under the guise of CSR- and ESG-driven morality.

The fallout from Black Monday was compounded by the U.S. Savings and Loan crisis42, which by the close of the 1980s had engulfed large portions of the American financial sector, resulting in an estimated $160 billion in losses—much of it ultimately transferred to the public balance sheet.

Less visible—but arguably more consequential—was the use of taxpayer-backed instruments during the Latin American debt crisis43. Under the banner of ‘debt forgiveness’—via the Baker and Brady44 Plans and so-called Debt-for-Nature Swaps—major banks were able to unload near-worthless Latin American bonds, often at 95 cents on the dollar or better. These transactions, totalling between $160–240 billion, amounted to financial sleight-of-hand more than meaningful relief, leaving the American taxpayer on the hook for a significant part of this covert bailout.

In its wake, the Brundtland Report45 called for coordinated action between public and private sectors in service of the so-called ‘common good’—in context of systems theory framed through the language of sustainable development and an emerging global ethic.

That same year, the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP)46, launched in 1987, was formally endorsed as a central research initiative for understanding global biogeochemical cycles. IGBP played a critical role in advancing the systems science behind sustainability policy, providing the data infrastructure that would feed into both IPCC and Agenda 21 processes.

Meanwhile, at the Fourth World Wilderness Congress47, the World Conservation Bank quietly introduced a financial mechanism that would underpin the later Rio Earth Summit treaties—UNFCCC and CBD—serving as the backbone of what would become a new model of environmental finance.

Around the same time, the Montreal Protocol48 provided a working precedent: emissions were to be curbed for the sake of the planet, but within a framework of transferable pollution rights. This laid an early foundation for commodified environmental governance.

In 1988, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change49 (IPCC) was formed—a mechanism that would go on to establish a new scientific orthodoxy around climate, laying the conceptual and technical groundwork for the future monetisation of carbon.

In 1989, the Hague Declaration on the Environment5051 was issued, calling for the creation of a supranational ecological governance body.

In 1990, the IPCC’s Working Group III52 formally endorsed carbon trading mechanisms as a viable tool for global emissions management.

Also in 1990, the Second World Climate Conference53 called for global satellite surveillance of the climate system—leading to the development of GCOS (Global Climate Observing System), GOOS (Global Ocean Observing System), and GTOS (Global Terrestrial Observing System).

In 1990, the International Human Dimensions Programme54 (IHDP) was officially launched at the Second World Climate Conference, marking the formal integration of social science into global environmental governance. It focused on the political, economic, and behavioural factors driving planetary change—complementing physical climate models with governance and development dimensions.

In 1991, the DIVERSITAS55 programme was established as a global science initiative on biodiversity, co-sponsored by ICSU, UNESCO, and UNEP, and with Peter Daszak56 on its roster. It aimed to produce integrated biodiversity research in support of the emerging Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), contributing scientific credentials to the framing of nature as a managed system within global governance.

In 1991, the Business Council for Sustainable Development57 (BCSD) was established—bridging the Brundtland vision with corporate-led Agenda 21 implementation, notably under the guidance of Maurice Strong and Stephan Schmidheiny.

In 1991, the ASCEND 2158 report was produced by ICSU and IIASA at the request of Maurice Strong—proposing a systems-analytic framework for sustainable development planning. Closely aligned with the emerging IPCC architecture, it advanced integrated modelling, scenario planning, and interdisciplinary science as tools for long-term global governance. It laid key conceptual groundwork for both Agenda 21 and the IPCC’s evolving role as a policy-guiding institution—particularly in mitigation strategy and future scenario construction.

That same year, the Global Environment Facility59 (GEF) was launched—effectively operationalising the earlier vision of the World Conservation Bank.

Also in 1991, the IUCN’s Caring for the Earth60 initiative articulated a coherent set of global ethical principles to guide the transition toward sustainable development.

In 1992, the publication of Combating Global Warming laid out the architecture for what would become the global carbon trading regime.

In 1992, the World Health Organization published Our Planet, Our Health61, establishing a direct link between ecological degradation and public health. It introduced a systems view of health as an outcome of environmental and socio-economic conditions, laying the conceptual groundwork for future frameworks like One Health and Planetary Health, and reinforcing the role of health as a legitimating narrative for global environmental governance.

Also in 1992, the CBD and UNFCCC treaties were formally launched at the Rio Earth Summit—establishing the foundational legal framework for global environmental governance, ultimately through carbon emission and sequestration.

That same year, Agenda 21 was introduced—quietly laying the groundwork for a future model of global governance managed through General Consultative Status NGOs, effectively placing the oversight of societal ‘common goods’ into unelected transnational hands.

In 1993, the ‘Global Ethic’ was explicitly detailed—sealing the moral framework that would justify this emerging architecture.

In 1994, the Caux Round Table62 published its Principles for Business, offering a moral framework for global capitalism rooted in human dignity and social responsibility. Emerging from dialogue between European, American, and Japanese executives, it aligned with the Global Ethic initiative and prefigured later ESG standards—embedding ethical codes into corporate governance as a tool of soft regulation and stakeholder alignment.

In 1995, the report Our Global Neighbourhood63 was released by the Commission on Global Governance. It proposed a redefinition of sovereignty, advocating for a new global ethic, the strengthening of international institutions, and the formalisation of multi-actor governance—essentially codifying the Brundtland vision into a long-term framework for post-national administration.

In 1995, UNESCO’s World Commission on Culture and Development64 released Our Creative Diversity, framing cultural identity, pluralism, and shared values as key components of a global ethic. It positioned culture not as an obstacle to governance, but as an instrument—emphasising the need for normative alignment in global development, and embedding ethical consensus within the broader architecture of sustainable governance.

In 1997, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan launched a sweeping reform agenda, restructuring the United Nations around global partnerships65. His plan deepened the UN’s alignment with corporations, NGOs, and financial institutions—ushering in a new model of networked governance in which public-private partnerships would be elevated as primary vehicles for planetary coordination.

The Ecosystem Approach66 (EA), formally adopted under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), marked a turning point in integrated landscape management—effectively embedding systems thinking into policy by treating land, water, and biodiversity as co-managed, interdependent units through principles of subsidiarity and a mediator approach.

The Kyoto Protocol67, signed the same year, codified carbon emissions trading and began operationalising the carbon monetisation framework first envisioned by IPCC Working Group III and outlined in Combating Global Warming (1992).

In 1998, the collapse of hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management68 (LTCM) prompted an unprecedented private bailout, quietly coordinated by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Though no public funds were used, the episode legitimised central bank mediation in rescuing systemically linked financial actors—setting a precedent for transnational crisis coordination among central banks and financial elites. It reinforced the logic that private risk could become public concern when framed as systemic—deepening the architecture of post-sovereign, discretionary economic governance.

In 2000, Wolfgang Reinicke published Trisectoral Networks, a framework that crystallised the logic of multi-stakeholder governance. Reinicke argued that effective global problem-solving now depended on coordinated networks of states, corporations, and NGOs—an idea that had long been implicit in Agenda 21 and was now explicitly endorsed as the operating model of transnational governance.

In 2000, the World Commission on Dams released its landmark report Dams and Development, co-convened by the World Bank and IUCN. It institutionalised a multi-stakeholder framework for evaluating large-scale infrastructure, embedding environmental and social impact assessments within the logic of transnational governance, and extending network-based oversight into the realm of development finance.

In 2000, the Earth Charter was officially released—providing a formal declaration of global ethical principles grounded in ecological responsibility, social justice, and intergenerational equity. Framed as a moral foundation for global governance, it echoed and extended the values laid out in Brundtland, Caring for the Earth, and Our Creative Diversity, completing the ethical architecture that underpins sustainable development discourse.

In 2001, the collapse of Enron—then one of the largest energy-trading firms in the world—triggered a global reckoning on corporate ethics and regulatory capture. It revealed the fragility of market self-regulation and catalysed a wave of governance reforms, including calls for stronger codes of conduct and transparency. The scandal further legitimised the push for embedded ethics within corporate structures, paving the way for ESG and stakeholder capitalism narratives.

In 2001, the Amsterdam Declaration on Global Change69 was signed by leaders of four major international science programmes—IGBP, IHDP, WCRP, and DIVERSITAS. It formally declared humanity a ‘major force of planetary change’, calling for integrated Earth system science and deeper collaboration across disciplines and sectors. The Declaration solidified the scientific consensus behind systems-based governance, positioning global environmental monitoring and modelling as essential instruments of planetary management.

In 2004, the concept of One Health70 was formally articulated at the Wildlife Conservation Society's ‘One World, One Health’ symposium in New York. Building on earlier frameworks linking ecology and health (as in WHO’s Our Planet, Our Health), it reframed zoonotic disease, food systems, and biodiversity loss as components of a single planetary health system. One Health institutionalised the logic of integrated risk governance, justifying expanded surveillance and intervention across human, animal, and environmental domains—further advancing the managerial paradigm of Earth system oversight.

In 2008, the collapse of Lehman Brothers71 triggered the largest financial crisis since the Great Depression, prompting trillions in coordinated central bank interventions, fiscal bailouts, and monetary expansion. The crisis marked a decisive shift: from market self-regulation to permanent state-market entanglement, justified by systemic risk logic. Institutions deemed ‘too big to fail’ became the structural beneficiaries of an emerging post-democratic financial order, paving the way for moralised capitalism and discretionary governance-by-crisis.

In 2009, the Earth System Governance Project72 was launched as the core science plan of the International Human Dimensions Programme (IHDP). Framing the planet as a governable system, it advanced a research agenda centred on architecture, agency, adaptiveness, accountability, and allocation—marking the full arrival of systems thinking as the normative and operational basis for global environmental governance.

That same year, the World Economic Forum’s Global Redesign Initiative (GRI)73 was introduced in collaboration with UN agencies, proposing a fundamental shift in global governance from state-based multilateralism to multi-stakeholder networks. GRI envisioned issue-specific coalitions of governments, corporations, NGOs, and experts as the new locus of authority—formalising a governance model in which legitimacy flows from functionality and network participation, rather than democratic mandate.

In 2009, the Global Economic Ethic Declaration74 was launched under the guidance of theologian Hans Küng and economist Jeffrey Sachs, calling for a shared set of moral principles to guide global capitalism in the wake of the financial crisis. Framed as a ‘common ground’ for ethical business and economic governance, it merged interfaith values with post-crisis economic reform, reinforcing the legitimacy of global economic coordination under a universalist moral banner.

Also in 2009, the Copenhagen Accord75 introduced a new climate finance architecture centred on blended finance and public-private partnerships (PPPs). Though the summit failed to produce a binding treaty, it marked a major shift toward using market instruments and multilateral guarantees to mobilise private capital for climate and biodiversity projects—cementing the logic of commodified planetary stewardship.

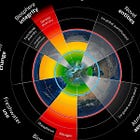

In 2009, the Planetary Boundaries framework was introduced by Johan Rockström and the Stockholm Resilience Centre. It identified nine biophysical thresholds—including climate change, biodiversity loss, and nitrogen cycles—beyond which Earth’s systems could allegedly destabilise irreversibly.

In 2012, the Future Earth initiative76 was launched as a global research platform for sustainability science, backed by the International Council for Science (ICSU), UNESCO, UNEP, and the WMO. Emerging as a successor to IGBP and IHDP, it integrated Earth system science with social sciences and policy design—explicitly positioning itself as the knowledge engine behind the Sustainable Development Goals. Future Earth marked a new phase in global governance: scientific networks not only informing policy, but actively shaping it through scenario planning, stakeholder engagement, and transdisciplinary foresight.

In 2012, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services is formed77.

In 2014, the Conference on Inclusive Capitalism, hosted in London and backed by the Rothschild Foundation and Vatican representatives, brought together CEOs, financiers, and public officials to reframe capitalism as a force for social cohesion78. Advocating long-term value creation and moral responsibility in markets, the initiative sought to reconcile profit with purpose—reinforcing the alignment between global finance, moral universalism, and stakeholder governance.

In 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were adopted by the United Nations, marking the formal convergence of environmental, economic, and social governance into a single global agenda. Presented as a universal framework for equity and sustainability, the SDGs institutionalised the telos of the Brundtland vision—serving as a normative roadmap for aligning national policies with transnational governance objectives.

In 2015, Blended Finance was formally codified through the Addis Ababa Action Agenda and embedded within the Sustainable Development Goals financing framework. It endorsed the use of public funds to de-risk private investment in global development projects—especially in climate, health, and infrastructure.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic79 triggered an unprecedented wave of deficit spending and central bank intervention, effectively normalising the monetisation of government debt. Under the guise of emergency response, the fiscal-monetary divide was quietly erased, paving the way for permanent forms of managed coordination—guided increasingly by multilateral institutions and crisis logic.

In 2023, the Fabian Society’s In Tandem80 report openly proposed the fusion of the UK Treasury and the Bank of England under a shared mandate to serve the ‘common good’, as defined by NGO networks and stakeholder coalitions outside of democratic legitimacy.

In April, 2025, policy advisor Manfred Bienefeld called for a new era of public-private partnerships for the common good, explicitly endorsing the use of blended finance, multilateral coordination, and moralised governance to manage planetary challenges. His proposal builds on Eduard Bernstein’s 1899 model of the public labour and private capital working together for ‘the common good’, managed by experts, intermediaries, and transnational actors operating beyond the boundaries of national democracy.

![WHO Pandemic Agreement [April, 2024]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!HHbL!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb69c8066-0498-4924-af63-1344abb2ec85_1206x612.png)