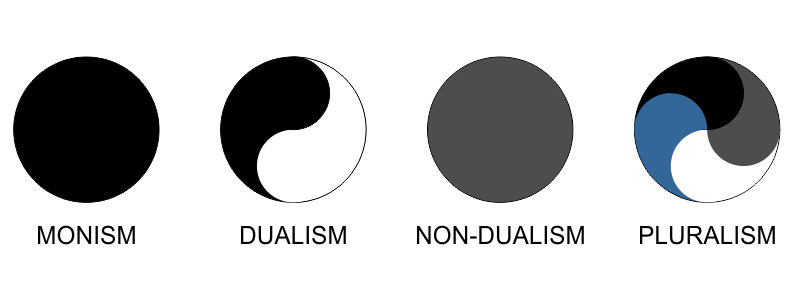

Monism

Through monism, Baruch Spinoza pioneered a vision of unity, where every part of the cosmos is linked. And this vision remains a cornerstone of contemporary monistic thought — and a testament to Spinoza’s enduring legacy.

Dualism is the view that reality comprises two fundamentally different kinds of substances or realms—most famously, the mental (spiritual) and the physical (material). In classical Cartesian dualism, René Descartes maintained that the mind is a non-material, thinking substance distinct from the body, which is material and extended in space. This perspective implies that mental phenomena and physical phenomena operate under different principles, and it raises profound questions about how a non-physical mind can interact with a physical body.

In contrast, monism asserts that there is only one kind of substance or fundamental reality, with all phenomena emerging as different expressions or aspects of this single essence. Baruch Spinoza, one of the most influential proponents of monism, argued that everything in the universe is merely a mode or attribute of one all-encompassing substance—often identified as ‘God or Nature’. According to Spinoza, the distinctions we commonly make between mind and matter do not indicate the existence of two separate entities but instead represent different ways of apprehending the same underlying reality. For him, attributes such as thought and extension are not separate realms but rather two sides of the same coin, reflecting the unity of existence.

Spinoza’s revolutionary monistic vision challenges traditional distinctions between the material and the spiritual. His magnum opus, Ethics, offers a radical departure from dualistic thought by dissolving the rigid boundaries that divide mind and matter. This unified framework, in which subjective experiences and objective phenomena are seen as interrelated aspects of one whole, has profoundly influenced subsequent philosophical debates and paved the way for later developments in science and philosophy—such as dual-aspect theories and neutral monism. Spinoza’s legacy endures as a cornerstone of modern monistic thought, continually inspiring contemporary discussions on consciousness, nature, and the interconnectedness of all things.

In a related tradition, Thomas Aquinas and the medieval concept of the Great Chain of Being also sought to reveal the underlying unity of all existence. Aquinas, drawing on Aristotelian insights, argued that every creature, from the simplest form of matter to the highest intellectual beings, occupies a place in an ordered continuum ultimately rooted in God. The Great Chain of Being visualised this seamless hierarchy, emphasising that all entities are interrelated parts of a single, divinely ordained reality. Though differing in emphasis from Spinoza’s monism, both Aquinas’ thought and the Great Chain of Being underscore a profound, integrative vision.

But upon closer inspection, Aquinas’ concept of Thomist realism—while maintaining a dualistic distinction between the material and the spiritual—introduces a unifying divine order. This order manifests as a hierarchically arranged, quasi-monistic framework in which every level of existence is interconnected and rooted in the divine. Even as Thomist thought clearly differentiates material and spiritual realms, this implies that all reality shares a common, divine order, hinting at an underlying unity.

In the post From Thomist Realism to the Omega Point, we explored the practical utility of this quasi-monistic order as a unifying principle. We argued that, from a materialist perspective, a similar drive toward systemic integration is evident in Bogdanov’s empiriomonism, which seeks to reconcile empirical data through a collectively-subjective perspective. Ergo, whether viewed through the lens of divine ordination or a collectively-subjective perspective of empirical reality, both frameworks provide a similar mechanism to interpret the universe.

Bogdanov’s Tektology was founded not merely on the notion of organisational order—a form of quasi-monism similar to that introduced by Aquinas, albeit with a different emphasis—but on a more expansive idea of scientific monism. Unlike traditional frameworks, Bogdanov‘s collectively-subjective perspective, in effect, imposes an order on empirical reality. Through empiriomonism, this ordering leads to a global ethic or universal moral framework, with Bogdanov—through Tektology, arguably the origin of systems theory—thus bridging ethical, organisational, and materialist monisms.

By further incorporating teleological monism—a perspective centered on purpose or final causes—we essentially arrive at a fourfold structural framework. In the context of systems theory, this integrated model closely resembles the multi-level structure described by Erich Jantsch in his 1970 paper on the Inter- and Transdisciplinary University: A Systems Approach to Education and Innovation1, wherein the purposive (teleology), normative (ethics), pragmatic (organisation), and empirical (material) dimensions collectively form a unified, coherent system.

In essence, we now have four levels of structured monisms in which each level directs the next: purpose informs ethics, which in turn shapes human organisation, which directs the people. But this naturally raises a question—if purpose is the driving force, what, if anything, lies beyond teleology?

As this isn’t of critical essence, here's the brief (details at the end). This conceptual lineage has even spurred a debate on the proper ordering of philosophical thought2.

Each level takes the abstract concepts of the previous layer and translates them into a practical framework or system. It’s like a cascade where transcendental ideas gradually become applied structures in the material world:

Transcendental Monism is pure unknowable potential, which Absolute Monism tries to conceptualise.

Absolute Monism’s totalising framework is manifested as the nature of being in Ontological Monism.

Ontological Monism becomes observable through the quantum field in Quantum Monism.

Quantum Monism challenges how we understand knowledge, leading to Epistemological Monism.

Epistemological Monism informs our sense of purpose in Teleological Monism.

Teleological Monism’s purpose is moralised in Ethical Monism.

Ethical Monism is institutionalised in Organisational Monism.

Organisational Monism creates the infrastructure for Scientific Monism to validate and optimise the process.

And do make a mental note that these layers are sequentially processed.

Returning to Jantsch, the essential point is that, in this context, monism functions as the focal point of a level in an organisational framework rather than merely a philosophical concept. Teleology (the purposive dimension) inspires ethics (the normative), which are then codified into law (the pragmatic) and ultimately enforced at the individual level (the empirical). Consequently, while Bogdanov employed empiriomonism, proletkult, and tektology to construct a conceptual mechanism of control, Jantsch implemented that teleological mechanism through Systems Analysis—a framework gradually refined through the efforts of Bertalanffy, Boulding, Churchman, and Ackoff.

And Systems Analysis, when paired with Input-Output Analysis, underpins contemporary active adaptive management. Furthermore, cybernetics—its core dynamic component—completes the circle by reflecting the foundational tenets of Thomist Realism as laid out by Aquinas, thereby in practise giving rise to -

Cybernetic Thomism.

Drawing a parallel between Spinoza’s Ethics3 and Jantsch’s framework4 reveals a substantial similarity in how both systems structure reality into four interrelated levels. In Spinoza’s scheme, we encounter four key elements: substance, attribute, mode, and God. Each of these elements finds a modern counterpart in Jantsch’s multi-level structure, creating an integrated vision of reality that spans from the observable to the teleological.

Substance = Empirical:

In Spinoza’s system, substance represents the underlying, all-encompassing reality—the singular, unifying entity of which everything is a manifestation. This corresponds with Jantsch’s empirical level, which encompasses the observable, measurable aspects of our world. Both perspectives treat this foundational level as the bedrock upon which all other phenomena are built.Attribute = Pragmatic:

Spinoza’s attributes are the essential qualities or properties through which the one substance is understood. They provide the means for comprehending the inherent order of reality. Jantsch’s pragmatic dimension mirrors this idea by focusing on the functional and organisational aspects that give structure to our experiences. Here, the emphasis is on how reality is arranged and made coherent through practical, systemic relationships.Mode = Normative:

Modes in Spinoza’s philosophy are the specific manifestations or expressions of the substance, representing the varied ways in which its attributes are experienced. This concept parallels Jantsch’s normative dimension, where evaluative, value-driven criteria shape behavior and establish ethical standards. In both systems, this level is concerned with the qualitative aspects that guide and regulate interactions within the broader system.God = Purposive:

For Spinoza, God is not an external deity but is synonymous with the substance itself—the ultimate, all-encompassing cause that unifies everything. This notion aligns with Jantsch’s purposive dimension, which serves as the final cause or overarching purpose that directs the entire system. Both views suggest that a fundamental drive or teleological principle underlies the apparent diversity of phenomena.

While the Great Chain of Being presents a fixed, hierarchical, intrinsic order—where every being has its specific place in a divinely ordained, rigid structure—Spinoza, in contrast, expands the idea of substance to show that every aspect of existence is simply a different expression of one underlying reality. In Spinoza’s system, what might be seen as successive levels (substance, then attributes, then modes) are not fixed in a predetermined order; rather, each level depends necessarily on the one preceding it. Spinoza hasn’t so much eliminated the notion of order as he has reframed it in terms of interdependent, functional relationships within an immanent, rational framework rather than a fixed, externally imposed hierarchy.

Consequently, in terms of imposing order—which flows top-down, one level at a time—it amounts to the same thing, as each level is processed only after the one preceding it is complete. The ordering is sequential, so when a given level is processed, its dependencies are already settled, and those of the following level will be settled upon the completion of the current.

By establishing these correspondences, it appears that Spinoza’s metaphysical framework—despite its historical context—aligns with modern, systems-based approaches to comprehending reality. Both Spinoza and Jantsch articulate a vision in which reality is organised in hierarchical layers, each level interdependent and directing the next, ultimately converging on a unified, coherent system that spans the empirical, pragmatic, normative, and purposive dimensions of existence. You could even plausibly argue that Spinoza’s version is a better match for Jantsch’s approach, which is founded in systems theory..

In that light, it is interesting to witness him dismissing the ideas of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, only to frame a viewpoint aligned with Neoplatonism through the lens of functionalism—accompanied by a strongly collectivist outlook that redefines freedom, immortality, truth, and morality. One might even say he ventures into troubled waters by insisting that God govern our fortunes entirely, thereby exonerating us from blame—and even portraying the devil as an agent acting on God’s behalf.

Perhaps his local synagogue in Amsterdam, however, understandably interpreted his stance quite differently at the time—especially given that his heretical opinions ultimately led to his excommunication in 1652.

Immanuel Kant emerged in the wake of rationalists like Spinoza, inheriting a tradition characterised by rigorous, systematic approaches to understanding reality. While Kant admired aspects of these systems, he found their deterministic implications—especially concerning free will—incompatible for a moral philosophy. In his critical philosophy, Kant reoriented the project of rational inquiry by asserting that although our knowledge of the natural world is constrained by causal laws, human beings must be regarded as free agents in the sphere of ethics. This dual stance both continues the systematic tradition of his predecessors and offers a critique, addressing the limitations of determinism — while still preserving the universality of rational inquiry.

Kant’s categorical imperative encapsulates this balanced approach, proposing a moral law that applies universally to all rational beings. By demanding that one act only according to maxims that can be universally willed, Kant provided a criterion for moral action that transcends subjective inclinations. This formulation not only marked a decisive break from earlier deterministic frameworks but also laid the groundwork for later ethical theories. Notably, Hermann Cohen and the Marburg School of Neo-Kantianism expanded upon Kant’s ideas, advancing a universal moral framework rooted in pure reason, while Paul Carus and the Neo-Friesian school worked to bridge religion and science through ethics. In this way, Kant’s categorical imperative can be seen both as a culmination of rationalist systematic thought and as a precursor to later developments in universal ethics.

With time, a universal moral framework evolved from Hermann Cohen’s thoughts through the contributions of influential philosophers such as Martin Buber, Emmanuel Levinas, and Hans Jonas. Their work—emphasising dialogue, infinite responsibility for the Other, and forward-looking stewardship—gradually broadened ethical concerns to include social, environmental, and intergenerational justice. And these would eventually be applied through mounting calls for ethical leadership also known as the principles of ‘Good Governance’.

These developments ultimately culminated in a call for a comprehensive global ethical system in 1993, where during the centenary celebration of the Parliament of the World’s Religions originally chaired by Paul Carus5 (with a notable mention of Felix Adler), Hans Küng introduced the concept of ‘A Global Ethic’, drawing on these diverse intellectual traditions to advocate for universal moral principles that transcend cultural and religious boundaries.

And this initiative gained momentum in particular through the Earth Charter, which in no uncertain terms constitutes a call for universal Planetary Ethics6.

And with this ongoing, Jacques Maritain drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights7 in 1948, with his brand of Neo-Thomism8 later fused into Vatican encyclicals through the Second Vatican Council9 (1962-65) and Populorum Progressio10 (1967).

Thus, tracing its evolution from Thomist Realism and Spinoza’s vision of an all-encompassing substance, through Kant’s reimagined ethics, to the emergence of contemporary global moral frameworks, this synthesis outlines reality as layered, yet unified. And in this context, monism serves as more than just a metaphysical proposition, but rather as these individual layers themselves.

And as Jantsch’s pioneering work in systems analysis reveals, this integrated monistic vision is not only an abstract ideal but also a practical blueprint for control. His framework demonstrates how these layers of monism—teleological, ethical, organisational, and scientific—can be mobilised to manage complex systems, where each level informs and constrains the next, translating metaphysical ideas into tangible mechanisms of governance through principles of adaptive management. And as this process is sequential, it is even functionally compatible with Spinoza’s functional monism.

And ultimately, this structured approach can be automated, serving the goal of maintaining alleged planetary health11 through the stewardship of all resources on Spaceship Earth—including humanity itself.

A more detailed analysis of how these layers integrate follows.

1. Transcendental Monism (Meta-Kosmic Monism)

Transcendental Monism represents the ultimate, unknowable source beyond all forms of comprehension, categorisation, or systematisation. This is the origin point of all existence, yet it remains entirely beyond human understanding or experience. It embodies the absolute mystery from which all other levels of monism emanate, a realm that transcends not only the physical but also the metaphysical, ontological, and epistemological domains. It is often equated with the ground of being or the void in mystical traditions, representing a space where nothing and everything coexist.

Transcendental Monism provides the conceptual origin as the unknowable source, while Absolute Monism represents the practical attempt to systematise and integrate this transcendence into a comprehensible whole. Absolute Monism makes the abstract mystery of Transcendental Monism accessible as a unified system.

2. Absolute Monism

Absolute Monism is the all-encompassing, integrative system that seeks to unify all aspects of existence into a singular, coherent whole. It is a totalising framework that absorbs distinctions, diversities, and dualities into a single reality or substance. This level asserts that there is no separation between mind and matter, spiritual and material, or subject and object. Everything that exists, whether physical, mental, or abstract, is part of a unified, holistic reality. Philosophers like Spinoza and mystical traditions have proposed similar ideas where God or Nature represents the singular essence of all that is.

Absolute Monism serves as the conceptual framework that suggests a totalising unity of all existence, while Ontological Monism is the practical exploration of this unity in the context of being itself. Ontological Monism takes the universal system proposed by Absolute Monism and applies it to understanding the essence of existence.

3. Ontological Monism

Ontological Monism focuses on the foundational nature of being. It posits that all phenomena, whether physical or conceptual, arise from a single, unified substrate of existence. This substrate could be material (as in physicalism), spiritual (as in idealism), or a combination of both. Ontological Monism asserts that existence itself is singular, and all apparent multiplicities are expressions or manifestations of this underlying unity. This level delves into what it means to exist and seeks to identify the essence or core of all things.

Ontological Monism provides the conceptual understanding of a unified nature of being, while Quantum Monism offers a scientific, practical manifestation of this unity. Quantum mechanics demonstrates how the singular essence of being translates into the physical behaviors of matter and energy.

4. Quantum Monism

Quantum Monism posits that the unified, probabilistic quantum reality underlies all matter and energy. It reveals that at the most fundamental level, reality is non-local, indeterminate, and entangled. Particles do not exist as isolated entities but as probabilities and potentialities within a single quantum field. This level challenges classical notions of determinism, causality, and separability, suggesting that the universe operates according to quantum principles that reflect a deeper unity.

Quantum Monism challenges traditional views of reality, necessitating a new framework for understanding how knowledge is formed. Epistemological Monism becomes the practical response to the conceptual shifts introduced by quantum mechanics, redefining how knowledge systems function.

5. Epistemological Monism

Epistemological Monism asserts that there is a unified structure and process of knowledge acquisition. It posits that all forms of knowledge, whether empirical, rational, or intuitive, stem from a singular epistemic framework. This level explores how we perceive, interpret, and understand reality, suggesting that there is a universal method or structure through which knowledge is generated and validated. It integrates insights from quantum mechanics, information theory, and philosophy of science to propose a cohesive understanding of how we know what we know.

Epistemological Monism provides the conceptual understanding of knowledge and reality, while Teleological Monism applies this understanding to define the universe’s purpose. The recognition of unified knowledge systems informs the idea that the universe has a directional goal.

6. Teleological Monism (Omega Point)

Teleological Monism posits that the universe is guided by an emergent purposive drive toward final convergence. This is often conceptualised as the Omega Point, where all aspects of the universe evolve toward higher states of complexity, consciousness, and unity. This level integrates scientific and spiritual perspectives, suggesting that the universe is not random or chaotic but has an inherent directionality leading to a predetermined goal.

Teleological Monism sets the conceptual stage by defining the universe’s purpose. Ethical Monism is the practical application of this purpose, translating it into moral principles that guide human behavior in alignment with the universe’s evolutionary trajectory.

7. Ethical Monism (A Global Ethic)

Ethical Monism asserts that there is a universal moral framework that applies to all beings and societies. This framework is aligned with the universe’s evolutionary and teleological purpose, suggesting that ethical behavior is that which promotes unity, complexity, and consciousness. It proposes that moral principles are not relative or culture-specific but are universal truths derived from the nature of reality itself.

Ethical Monism provides the conceptual foundation for universal moral frameworks, while Organisational Monism represents the practical implementation of these ethics within institutions and governance systems.

8. Organisational Monism (Thomist Realism/Empiriomonism)

Organisational Monism advocates for governance and institutional structures that embody and enforce ethical and teleological principles. It proposes that all institutions—political, social, and economic—should be aligned under a unified system that reflects universal moral truths. This level focuses on creating cohesive structures that promote global unity and harmonious coexistence.

Organisational Monism provides the structural and institutional support for scientific endeavors, while Scientific Monism serves as the practical tool to empirically validate and optimise the principles and structures derived from the entire monistic hierarchy.

9. Scientific Monism

Scientific Monism posits that all phenomena can ultimately be understood and explained through empirical systems and scientific methodologies. It suggests that science is the primary tool for validating and optimising the universe’s evolutionary process. This level integrates the ethical and teleological principles established in previous levels into a cohesive scientific framework that drives technological progress and planetary stewardship.