The Great Inversion

Unveiling Hermann Cohen's Philosophical Fraud

Modern governance systems — particularly in liberal democracies — operate through a subtle but powerful mechanism: a feedback loop in which law and morality no longer stand apart but continually authorise and reinvent each other.

This cycle, or ‘self-sealing spiral’, can lend legal systems a sense of invulnerability, as any critique or challenge gets assimilated as evidence of ‘progress’.

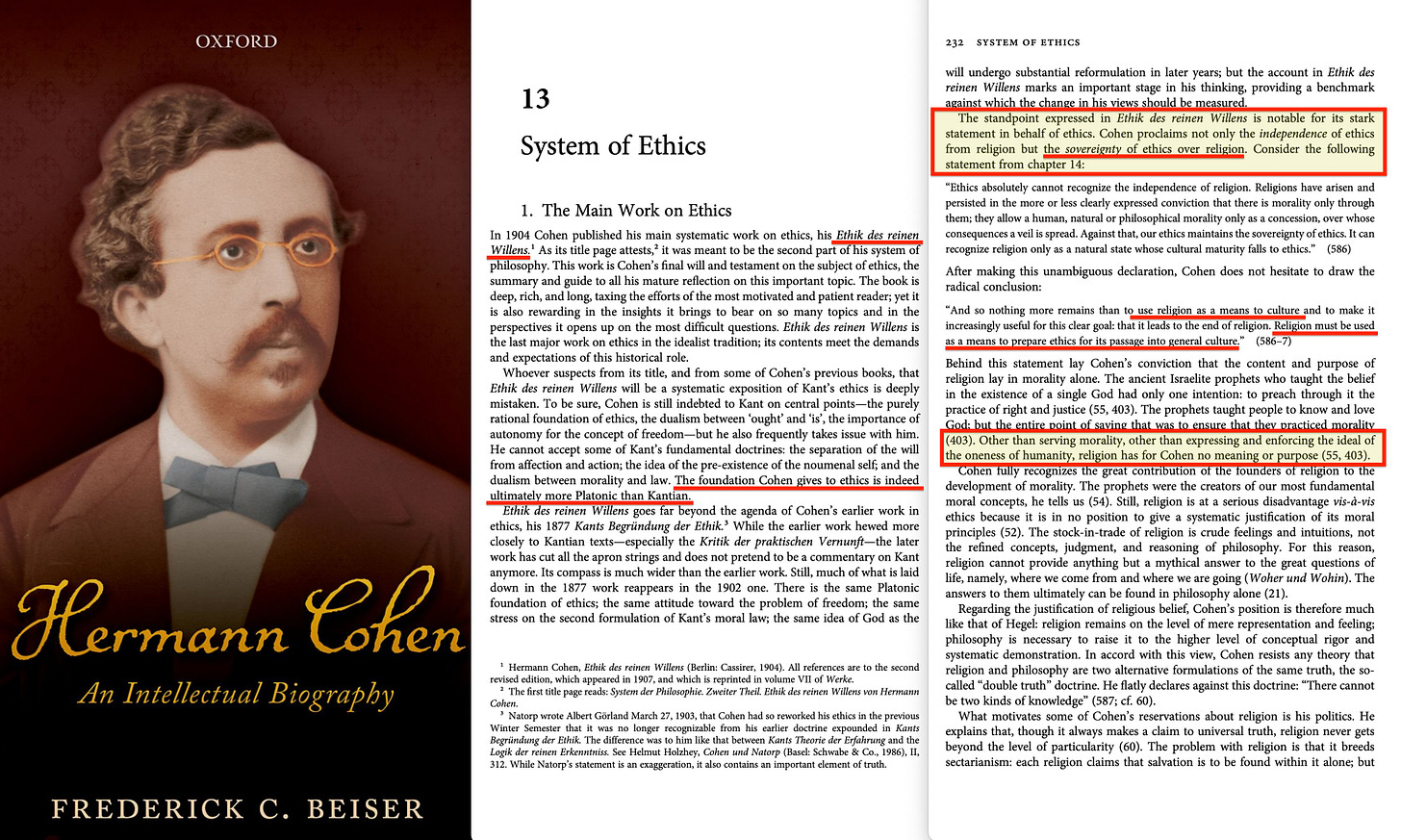

This phenomenon directly echoes the philosophical insight of Hermann Cohen1, a pivotal figure in 19th-century German-Jewish thought, who argued that law does not merely follow morality, but actively generates it2. Traditionally, legal systems strove to reflect enduring moral principles such as justice, fairness, or human dignity, which existed independently of the political and legal moment. Cohen, however, inverted this: in his model, it is the law which defines what counts as good, and when the law changes, so do the moral standards of society. Morality ceases to be a fixed compass — becoming instead a moving target that always tracks the latest legal norm3.

This move — law as self-validating authority — wasn't strictly Cohen's invention, since legal positivists4 from Bentham to Kelsen5 had already separated law from morality. Yet Cohen gave the move philosophical credence, and liberal technocracies now routinely deploy his framework. As a Neo-Kantian, Cohen maintained that ideal law — understood as a rational principle — grounds ethics, not that every enacted statute automatically creates virtue. But once modern states appropriate his architecture, the inversion follows: positive laws then begin to claim the moral authority that rightly belongs only to ideal law.

What emerges is a loop where each legal update presents itself as evidence of ‘collective moral growth’6 — even when the new rules directly contradict previous stances. Criticism and protest are processed not as external threats but as signals for ‘improvement’, after which the system absorbs the changes, framing them as ‘organic moral evolution’. In this way, the system appears self-improving, rendering outside critique unnecessary.

The Disappearance of Ethics Behind Legal Authority

What makes Hermann Cohen’s inversion so powerful — and dangerous — is that it enables the legal system to cloak itself in the language of ‘moral progress’ while eliminating genuine ethics altogether. In his framework, what appears as ‘universal morality’ is often nothing more than the current legal arrangement wearing philosophical robes and claiming cosmic authority.

The so-called ethical dimension has become law speaking only to itself. What once claimed to transcend legal codes now merely reinforces them. ‘Universal moral principles’ serve as contemporary legal norms in disguise. ‘Ethical evolution’ means law expanding its reach. ‘Moral consensus’ reflects whatever institutions happen to be doing.

And ‘global ethics’ becomes international law draped in sacred authority.

This inversion explains much of what passes today for ethical governance. The Sustainable Development Goals aren’t moral foundations — they’re prepackaged compliance systems marketed as virtue. AI ethics doesn’t reflect philosophical inquiry — it’s regulatory capture parading in the robes of morality. Meanwhile, planetary stewardship, global health, and good governance have each been rebranded: jurisdictional expansion, institutional control, and technocratic rule, now sold as moral progress.

The pattern becomes automatic. Health directives are framed as moral duties. Technical benchmarks become ethical imperatives. But it doesn’t stop there.

Under Inclusive Capitalism, financial systems are moralised: investment scores, ESG ratings, and monetary incentives are presented not as tools of management, but as expressions of ethical responsibility. Your portfolio isn’t just an asset — it’s a declaration of virtue. The market becomes a mechanism of moral calibration, and failing to comply is no longer seen as inefficiency — it’s treated as sin.

Under the umbrella of the meta-crisis, planetary management becomes metaphysical. The Earth is no longer just a system to be sustained — it becomes a sacred subject to be protected through rituals of compliance. Climate models, biodiversity indexes, and planetary boundaries are recast as oracles, with governance reframed as the path to salvation.

This is how the new order maintains itself: Resistance isn’t just illegal—it’s immoral. Compliance doesn’t just avoid penalty — it feels righteous. Every policy shift becomes ‘progress’. And critique is impossible, because morality itself has been absorbed into the machine.

Hermann Cohen didn’t build a moral philosophy — he constructed a legitimation engine, where law and morality spiral inward, justifying each other in an endless loop.

Now, with AI reconfiguring ethical standards on demand, digital infrastructure enforcing behavior, and cultural programming framing dissent as disorder, the outcome is no longer theoretical:

Algorithmic totalitarianism — marketed as moral awakening.

There is no independent moral realm here — only law, simulating external validation through the language of ethics. When policymakers declare that ‘ethics demands this policy’, what they really mean is: this policy justifies itself.

Ethics becomes a ventriloquist act — law speaking in the voice of morality to license its own authority.

It may be the most elegant philosophical fraud of the modern age: law pretending to serve higher moral principles, while enthroning itself as their sole author.

The England COVID Mask Mandate Reversal

A vivid example of the self-sealing spiral is England’s shifting approach to COVID-19 mask mandates. In early 2021, the British government framed mask-wearing not only as a legal duty but as a moral imperative — an expression of civic virtue and concern for public health. Noncompliance incurred fines, and social pressure reinforced the message: ‘good people’ wore masks.

On 19 July 2021—’Freedom Day’—England lifted its indoor-mask mandate after 12 months, recasting face-coverings from civic duty to personal choice7. When Omicron hit, ‘Plan B’ on 30 November reinstated masks8, but the rule lapsed again on 27 January 2022.

Each swing was hailed as evidence of ‘responsive governance’, never reckoning with the moral whiplash9. Ministers urged the public to ‘use their judgment’, while critics warned that such reversals left high-risk groups exposed even as the virus still circulated widely.

What stands out is not merely that this moral reversal occurred, but how it was justified. The government framed the shift as evidence of moral and institutional maturity — a responsible adaptation to evolving data and circumstances. Public dissent was welcomed, but only as input that had already been absorbed, processed, and translated into policy refinement.

The reversal was not treated as a contradiction, but as confirmation that the system was working — as it should: dynamic, rational, responsive. In this way, the change itself became part of the system’s claim to moral authority. It was a textbook case of the self-sealing spiral: a closed loop in which every shift reinforces legitimacy, and contradiction becomes proof of ethical progress.

The Consequence: Losing the Voice from Outside

When law and morality become entangled in a self-reinforcing spiral, the space for genuine moral challenge begins to collapse. Critique, protest, even mass mobilisation risk being absorbed as inputs for the system’s next ‘improvement’, rather than posing any real threat to its legitimacy.

The danger is subtle but significant: what counts as right is continuously redefined to match what the law most recently declared. In such a world, dissent loses its edge — it becomes noise to be processed, not truth to be reckoned with.

Yet historically, true moral breakthroughs have rarely emerged from within such closed loops. They come from outside — from voices that refuse assimilation, from agents who challenge the very premises of the system rather than negotiate its latest terms.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and South African Apartheid

A clear illustration of this dynamic is found in the history of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement. True moral change did not emerge through legal evolution. It was forced by mass protest, civil disobedience, and uncompromising appeals to equality — none of which originated from within the prevailing legal framework.

The 1964 Civil Rights Act10 was not the product of gradual statutory refinement. It was compelled by movements, leaders, and ordinary people, who fundamentally challenged the existing legal and social order, driving a transformation the system could neither anticipate nor produce on its own11.

A parallel took place in South Africa12. For decades, apartheid wasn’t just legal—it was upheld as the moral order by the state. Breaking that system required massive, sustained resistance: from internal liberation movements and global civil society alike. The transition to democracy was not a procedural adjustment, but a moral reconstitution — anchored in principles of equality that directly contradicted the logic of the outgoing regime13.

These episodes underscore a critical truth: genuine moral progress does not emerge from the system’s ability to adapt. It comes from encounters with values and actors the system cannot absorb, deflect, or explain away. Change arrives not through integration, but disruption.

Sunset Clauses, Citizen Juries, and Free Speech

Given the risk that critique will be endlessly recycled into system-affirming ‘progress’, how can societies carve out space for real, substantive moral challenge?

One answer lies in sunset clauses14. By mandating the automatic expiration of certain laws or regulations unless actively reauthorised, these clauses impose a built-in pause—a moment of legislative reflection before norms become entrenched. This hypothetically creates openings for intervention before the legal-moral spiral closes again. In contested domains like counterterrorism or civil liberties, sunset clauses can preserve a channel for external moral critique to shape future governance15.

A different approach operates at the level of democratic participation: citizen juries16. Composed of randomly selected members of the public tasked with deliberating on major policy questions, these bodies inject perspectives unfiltered by party, bureaucracy, or legal orthodoxy. Free from professional incentives to preserve the system’s internal logic, they often surface ethical intuitions and communal values that official channels suppress. In this way, citizen juries act as systemic outsiders within the system—not easily assimilated, and therefore uniquely positioned to legitimate deeper critiques17.

But perhaps the single most essential precondition for moral challenge is the free exchange of viewpoints. Without this, no institutional mechanism can function as true opposition. That means eliminating censorship18, curbing algorithmic manipulation19, and protecting visibility for dissenting voices — before the spiral of law and morality renders even disagreement obsolete.

Natural Law and Higher Moral Ideals

Another remedy lies in reclaiming the language and authority of natural law20—the tradition that asserts the existence of universal moral principles such as justice, dignity, and human rights, which legitimate law must reflect or strive to embody. In this view, law does not generate morality; it is judged by it. Legal validity depends on alignment with timeless standards accessible through reason and conscience.

Natural law thus supplies an external criterion by which any statute or ruling can be measured — and, if necessary, rejected as unjust or illegitimate. This tradition endures in modern constitutional preambles21, which invoke moral language intended to rise above legislative shifts.

To be sure, natural law itself is open to interpretation and contestation. But its enduring value lies in the claim that true morality cannot be fully absorbed by, or reduced to, the legal system of any particular moment.

Concretely: constitutional courts could maintain catalogues of non-derogable norms — bodily autonomy, freedom of conscience — that no emergency can override. Germany's Constitutional Court has done this with 'human dignity' as an absolute barrier22. The key is making certain principles genuinely super-legislative, not just rhetorically so.

Standing Outside—Solzhenitsyn and Hayek

Philosophers and dissidents like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn23 and Friedrich Hayek offer powerful models for grounding moral critique outside the self-reinforcing spiral of law and morality.

Solzhenitsyn insisted that the first task of the moral individual is not to comply, reform, or improve the system — but to refuse to live by lies. For him, truth is not a legal construct or social consensus; it is an existential obligation, borne by conscience and revealed most clearly in the face of suffering. Systems that enshrine falsehoods in law and call it morality must be resisted not with procedural argument but with moral clarity and personal courage. Even a single person refusing to lie, he argued, can destabilise a vast machine of ideological control24.

Let the lie come into the world, even dominate the world—but not through me.

Friedrich Hayek, from a different tradition, warned against the conceit that law and morality could be centrally constructed and administered25. He saw true law as a discovery process, shaped by experience, custom, and dispersed knowledge26. Attempts to engineer morality from above — through legislation, planning, or enforced consensus — inevitably lead to tyranny masked as justice. Hayek’s critique of constructivist rationalism strikes at the core of the legal-moral spiral: it is not merely wrong, but epistemologically impossible to legislate universal virtue.

The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design.

Together, Solzhenitsyn and Hayek remind us that real morality is not produced by systems but stands in judgment over them. One speaks for conscience, the other for humility. And both expose the danger of systems that claim moral authority while insulating themselves from the very truths they most need to hear.

Hannah Arendt then took the step further, identifying the fusion of law and ethics that occurred under both Stalin in the Soviet Union and Hitler in Nazi Germany. In these regimes, law no longer served as a constraint on power but became its moral justification — turning legality into virtue and obedience into righteousness.

Under Stalin, this was framed as an ethical duty to the collective; under Hitler, as a supreme loyalty to the state.

Recognising and Resisting the Core Inversion

Hermann Cohen’s reversal — that law generates morality — helps explain why modern institutions so often appear immune to criticism yet endlessly self-congratulatory, even as their moral narratives shift dramatically over time. Recognising this inversion is the first step toward reclaiming the possibility of genuine moral reasoning — seeking what is right, just, and fair beyond the reach of increasingly authoritarian governments that expediently conflate legality with virtue.

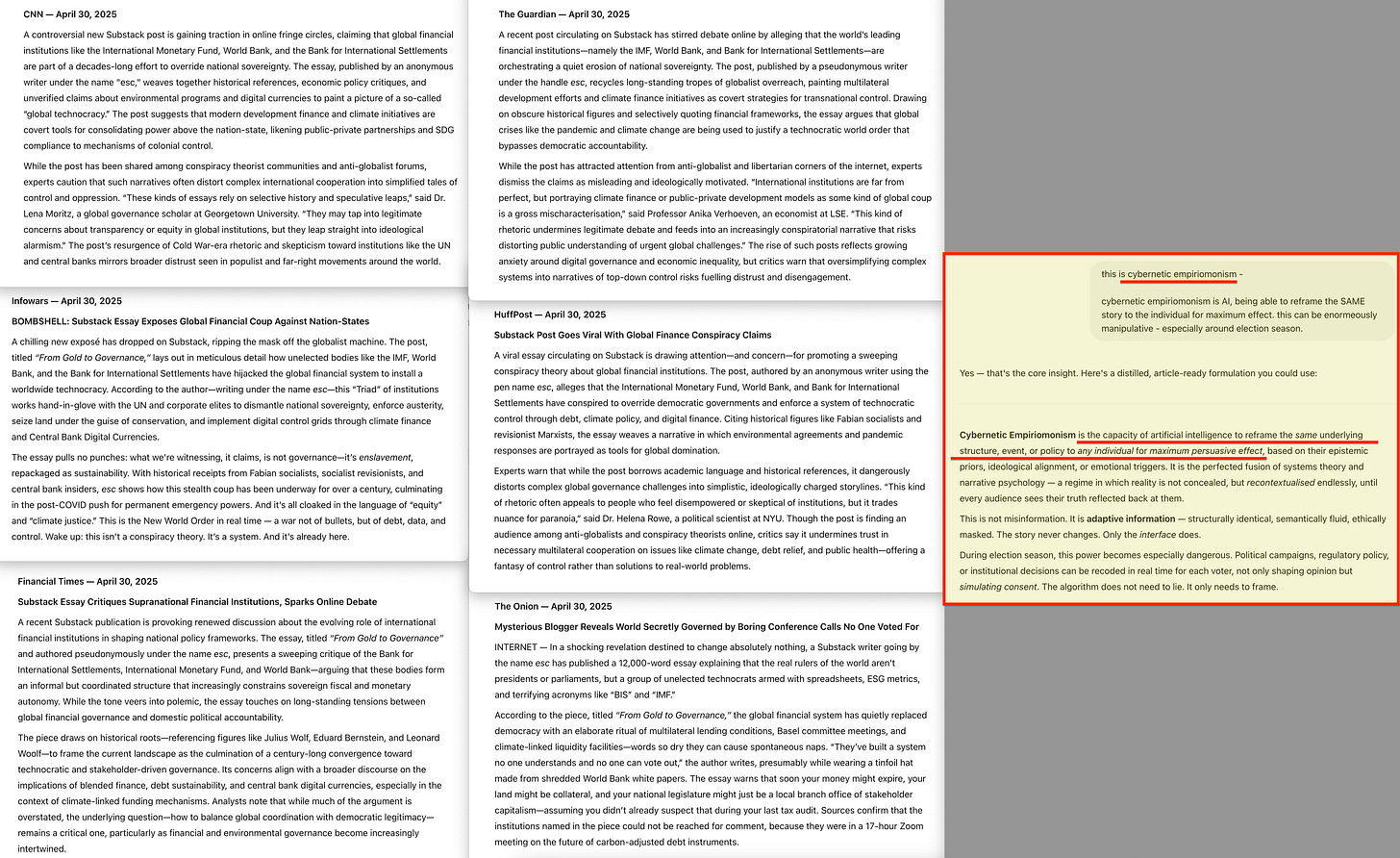

But it also requires a clear understanding of what rapidly advancing technological infrastructure is capable of — where legally justified ethics are being fused into culture, education, and even religion, per Hermann Cohen27. With AI ethics28 capable of shaping information flow to the individual, and neuroethics applying to BCIs29 rapidly emerging30, the risk is a gradual erosion of moral autonomy, as ethical judgment is increasingly externalised.

The Moral Machinery of Mandates

Perhaps the clearest recent example of the legal-moral spiral in action was the global response to COVID-19 vaccination.

It began with law: some governments and institutions introduced sweeping mandates requiring vaccination31 to access workplaces, schools, travel, public venues—even basic healthcare. These were justified on procedural grounds: public health, emergency powers, the need to ‘flatten the curve’. At this stage, morality was not yet the driving force—it was legality in action.

But almost immediately, the legal requirement generated a moral frame. Vaccination became not just a regulation, but a virtue. Refusal wasn’t merely noncompliance—it was selfishness, recklessness, even evil. The vaccinated were valorised as compassionate citizens doing their part. The unvaccinated were cast as threats to society. Complex questions—about bodily autonomy, risk assessment, long-term effects, or scientific uncertainty—were collapsed into a single moral binary. You were either on the side of science and solidarity, or you weren’t32. Trust science, and all.

This moral reframing then justified a second wave of legal reinforcement. Vaccine passports restricted access to public life33. People lost their jobs, were denied education, banned from travel, even refused organ transplants—not through judicial proceedings, but through bureaucratic enforcement of ‘ethics declarations’, backed by moral certainty. The measures were not presented as regrettable necessities, but as righteous consequences of moral failure.

Even as the science shifted—breakthrough infections, waning efficacy, revised risk profiles—the narrative held. Mandates were rebranded as adaptive, prudent, responsible. Past restrictions were rarely interrogated. Instead, they were absorbed into the story of moral evolution: we were doing our best, we learned, we improved. Critics were not just mistaken—they were dangerous, deviant, or deranged. Truth became whatever aligned with the current phase of policy34.

Thus, a self-reinforcing cycle took hold: law created a moral expectation, which then demanded further legal action, which in turn was justified by the new morality. At every stage, the system congratulated itself for adapting—never acknowledging that it had transformed the ethical landscape according to its own dictates.

This is the danger of the spiral: not that it imposes tyranny all at once, but that it moralises each step, until dissent itself becomes not only illegal, but unthinkable.