Codex Alimentarius

The food on your supermarket shelf, the pesticides your local farmer can use, and the agricultural policies your government pursues are all influenced by international bodies who operate through two distinct channels: hard enforcement via trade rules, and soft enforcement via norms, ratings, and advisors.

When Sri Lanka followed the soft path in 2021, its agricultural sector collapsed within months, food prices doubled, and the president fled as protesters stormed his palace.

The same pressures now bear down on European farmers.

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation was established in 1945, with John Boyd Orr as its founding Director-General1. Four years earlier, Orr had participated in the ‘Science and World Order’ conference in London, where Julian Huxley, JD Bernal, and Joseph Needham among others outlined their vision for a world managed by technical experts rather than elected politicians.

Orr carried this philosophy into the FAO, and his successors have expanded upon it for eight decades.

The FAO’s original mandate was ending hunger. Over time, this has broadened to encompass ‘food systems transformation’ — a programme reaching into agricultural practices, land use, dietary guidelines, and rural development across 194 member nations.

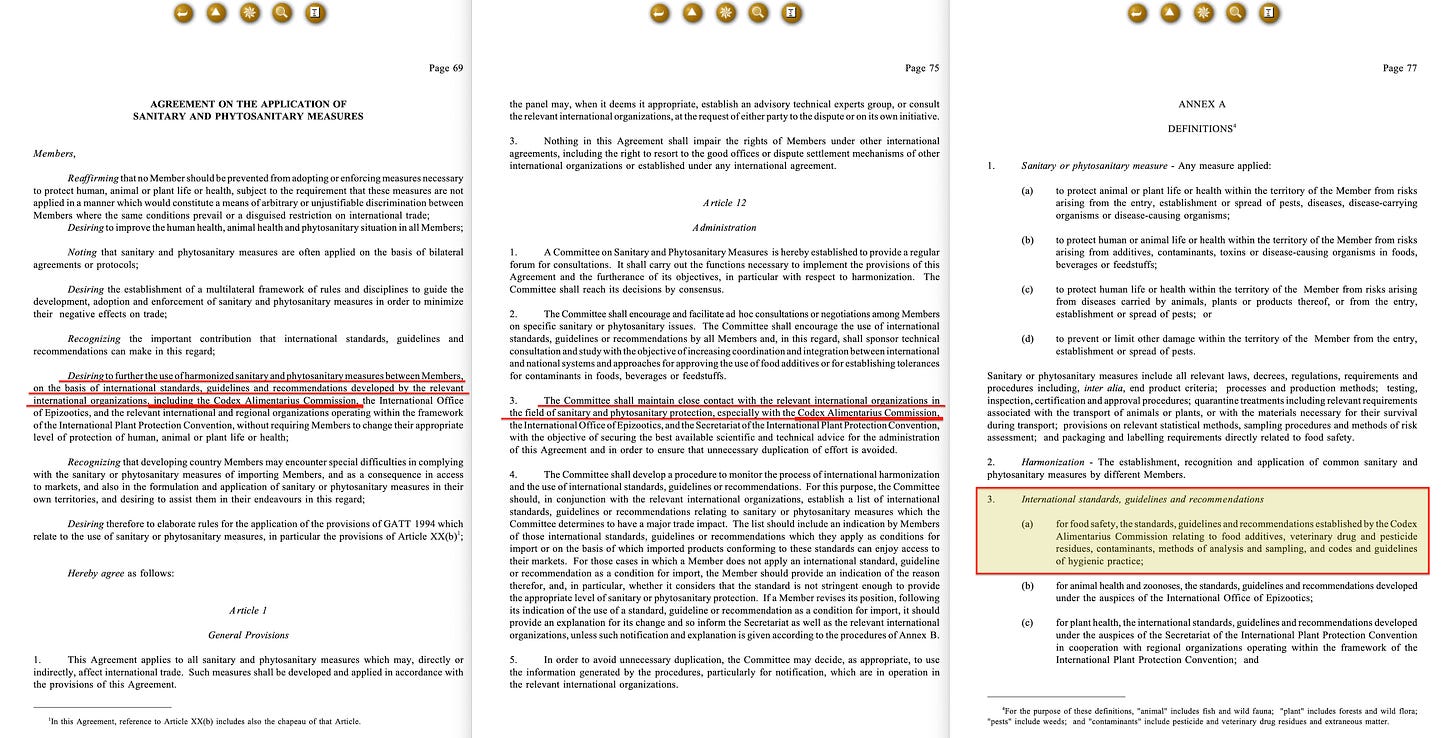

The hard enforcement channel runs through the Codex Alimentarius Commission2, established jointly by the FAO and the World Health Organisation in 1963. Codex develops standards covering pesticide residue limits3, food additives4, and labelling requirements5. These standards are formally voluntary, but when the World Trade Organisation was established in 19956, its Agreement on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures7 designated Codex as the reference standard for food safety disputes. If your country’s regulations differ from Codex standards and a trading partner challenges them, the burden falls on you to prove your rules are scientifically justified. Failure authorises trade sanctions.

The architecture mirrors financial regulation precisely. The Financial Action Task Force sets anti-money-laundering standards that are technically voluntary, but countries that fail to implement them are grey-listed and their banks lose access to international finance. Codex operates identically: formally optional, practically compulsory, with enforcement through market exclusion rather than law.

The soft enforcement channel operates differently but produces similar outcomes. It runs through UN Sustainable Development Goals8, World Economic Forum promotion9, ESG ratings10, and networks of advisors who carry the message into national governments.

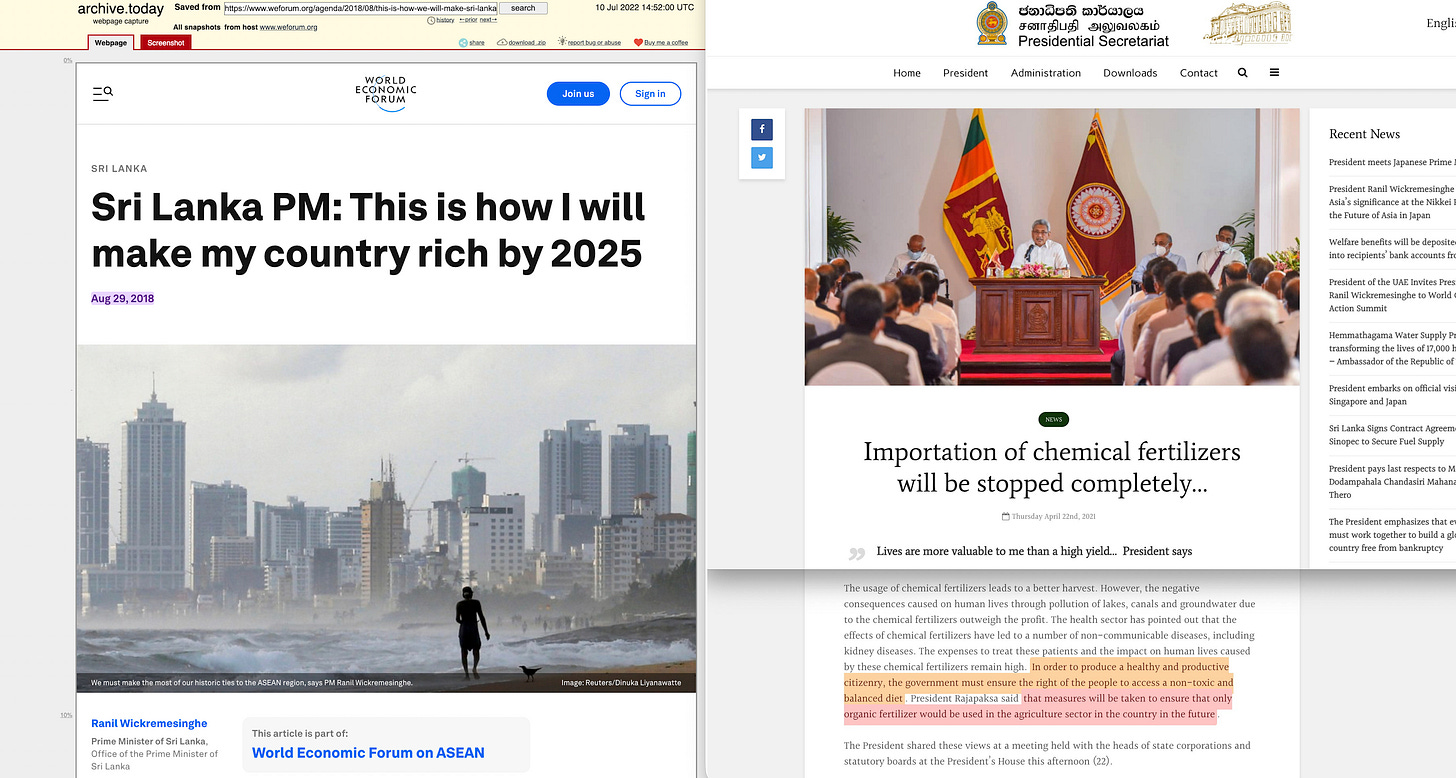

Sri Lanka demonstrated how this channel works. In April 2021, President Rajapaksa banned synthetic fertiliser imports, explicitly aligning Sri Lanka with SDG targets for reduced chemical inputs and sustainable agriculture11. The policy had been encouraged by Vandana Shiva, an Indian activist with no formal agricultural training who had advised Rajapaksa on organic transition. At a UN Committee on World Food Security event in June 2021, Rajapaksa announced the ban as ‘resolute policy action’ for agroecology12 — and received applause from FAO officials who praised it as a bold step forward.

Within months, rice production fell twenty per cent, tea yields collapsed, and food prices placed basic nutrition beyond ordinary families’ reach. By mid-2022, protesters occupied the presidential palace and Rajapaksa fled abroad13.

The international response was revealing. The World Economic Forum quietly deleted articles that had praised Sri Lanka’s sustainability ambitions, including a 2018 piece by Rajapaksa himself14. Throughout the famine, Sri Lanka maintained an ESG rating of approximately 9815 — the metrics continued rewarding compliance even as people starved. The UN issued no revision to its recommendations.

No treaty compelled Sri Lanka’s ban. No trade sanction enforced it. The soft channel operates through norms without mandates, advisors without accountability, and ratings that measure compliance rather than outcomes.

The same dynamics now operate in Europe, driven by the 2022 Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework16 requiring 30 per cent of land and sea to be ‘protected’ by 203017.

The Netherlands already protects between 20 and 26 per cent of its land, with strict Natura 2000 areas covering around 9 per cent — yet Dutch farmers still face court-ordered nitrogen cuts, with forced closures looming for thousands of operations18. Government buyout schemes worth over €1.5 billion target high-emission livestock farms19. Even a country close to the 30 per cent target cannot escape the squeeze, because the protected land must come from somewhere — and that somewhere is working farms.

Denmark faces a starker arithmetic. Only 14.9 per cent of Danish land is currently protected, meaning the country must somehow find another 15.1 per cent to meet the 2030 target. The Danish ‘Roadmap for Sustainable Transformation’20 — the policy document charting this transition — lists 274 contributors. The overwhelming majority are academics. Farmers, whose livelihoods depend on the outcome, are virtually absent from the process that will determine their fate.

The pattern is consistent: international targets set without democratic input, national policies developed without consulting those affected, and when implementation produces disaster, the institutions responsible attribute failure to local mismanagement and continue unchanged.

The same architecture operates across domains. Hard enforcement through trade conditionality. Soft enforcement through norms, ratings, and expert networks. Both channels bypass democratic deliberation, both shield international bodies from accountability, and both continue unchanged when policies fail.

British farmers comply with standards shaped in Rome and Geneva21. Understanding how both paths of compliance are engineered (through functionalism22) is the first step toward changing it.

I'm extremely cautious with any criticism of Vadana Shiva and suspect her failures were not ideological but agency-based. How much could she actually influence given farmers ties to debt based on trade that is international in scope not local. I think there well maybe many devils in that detail. Few have worked as tirelessly and relentlessly to combat the 'green revolution' which has been a direct road to local starvation and servitude.

Great bloody info though.

Your research reads as if a whole team is supporting you in finding and reading all the documents on matters that have been my topic for 15 years (or is that AI), as The Netherlands are one of the main 'agenda'-supporters since the 70's, and developers (pe Natura 2000, habitat directive etc). Is it possible to contact you, as you are an excellent candidate for an interview for the Dutch newspaper I write for: you may contact me, Rypke at +31 6 24162988. Thank you for al the good work and inspiration