The Financial Action Task Force

The Financial Action Task Force was created at a G7 summit in Paris in 1989 to fight drug money laundering1. It wasn’t established by treaty — that would have required parliamentary approval.

They simply announced it existed.

FATF writes forty recommendations2 covering how banks should identify customers, monitor transactions, and share information with governments — which in practice requires comprehensive financial surveillance.

These recommendations are technically voluntary, but FATF also maintains two lists that in effect make compliance mandatory. Countries on the ‘grey list’3 face extra scrutiny from international banks, making every transaction slower and more expensive. Countries on the ‘black list’ can be cut off from international banking entirely, which for a modern economy is catastrophic.

Crucially, FATF in 2019 received an open-ended mandate4. It can expand its scope without returning to any legislature for approval — and it has, repeatedly.

What Else Was in That Document

The 1989 G7 communiqué that created FATF5 contained an extensive section on the environment — explicit discussion of greenhouse gases and climate change, endorsement of the recently-created IPCC6, a call for what became the UNFCCC climate treaty, and language anticipating the 1992 Rio Earth Summit.

Paragraph 38 states: ‘In special cases, ODA debt forgiveness and debt for nature swaps can play a useful role in environmental protection’.

Lovejoy’s Debt-for-nature swaps had only been trialled two years earlier7. Understanding why they appear in the same document as financial surveillance requires going back further, to a twelve-year process that reveals both mechanisms were designed together.

The Longer History

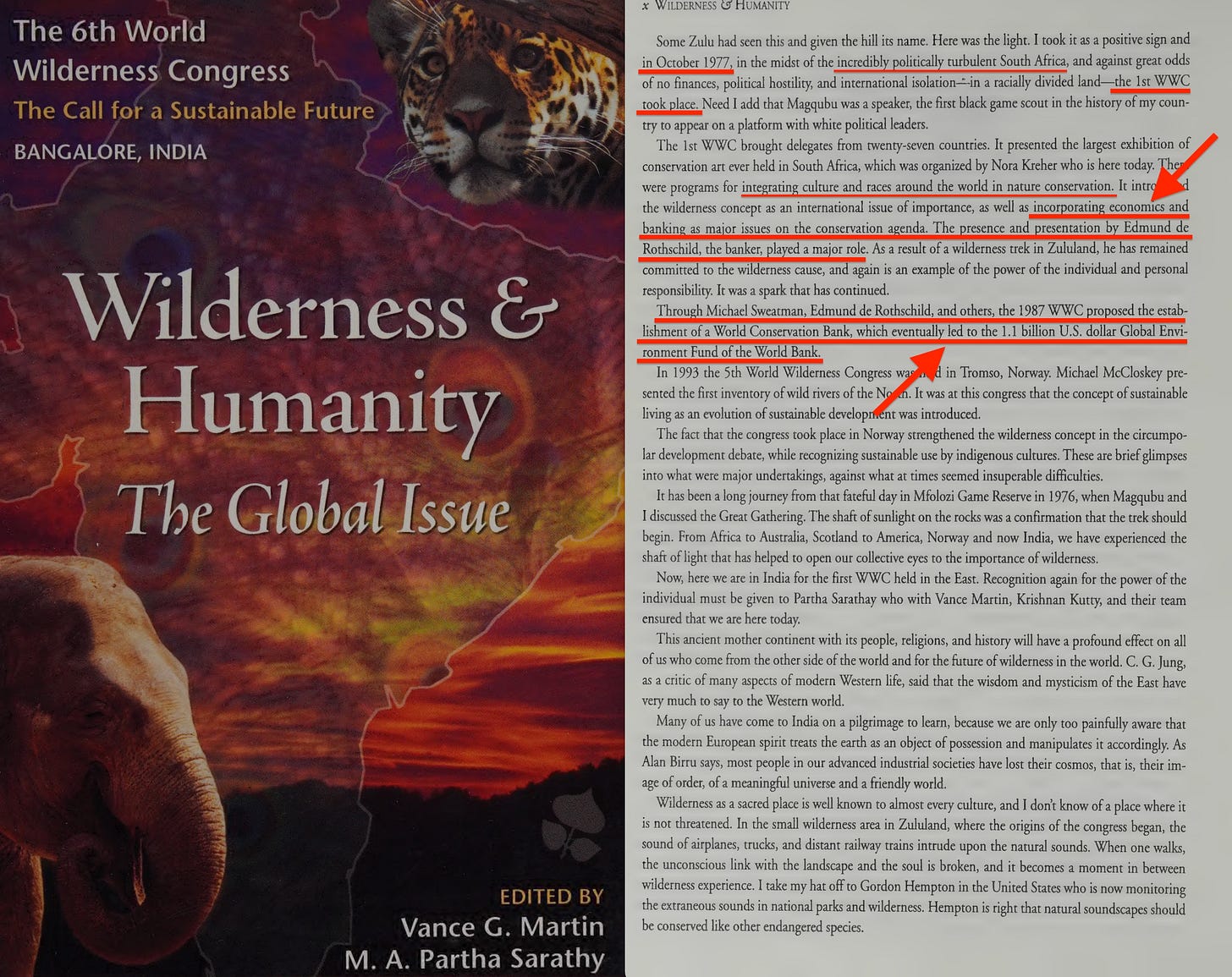

The first World Wilderness Congress8 took place in Johannesburg in 1977. Edmund de Rothschild spoke about ‘incorporating economics and banking as major issues on the conservation agenda’, and according to later congress proceedings, his presence ‘played a major role’.

He included Teilhard in his talk, which concluded with a Nietzsche quote that captures the vision being developed: ‘How should the earth as a whole be administered? To what end should man, no longer a people or a race, be raised and bred?’

Van der Post, who co-founded the congress and wrote the foreword to the proceedings containing Rothschild’s speech, became Prince Charles’s spiritual mentor that same year9.

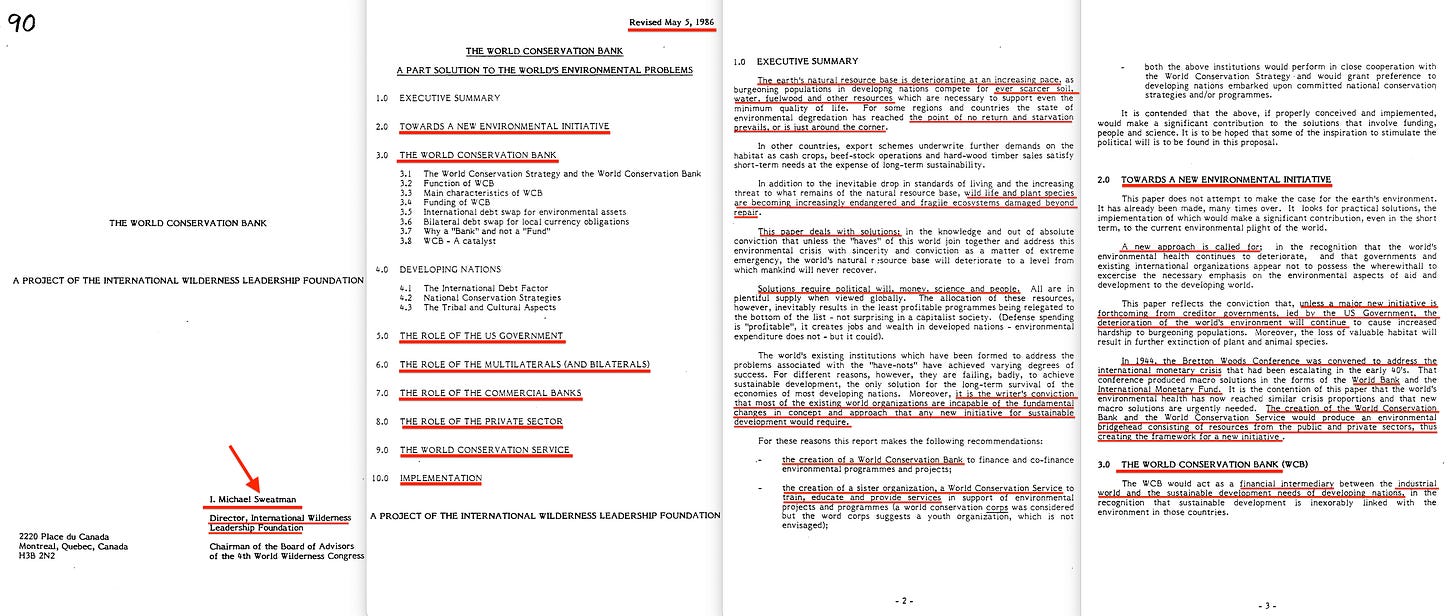

By 1984, Michael Sweatman — a director of the International Wilderness Leadership (WILD) Foundation — had developed a proposal for a ‘World Conservation Bank’. Thomas Lovejoy floated debt-for-nature swaps in the New York Times10 that same year. Sweatman’s proposal reached the World Commission on Environment and Development in 1986 and appeared in their landmark Brundtland Report11 the following year.

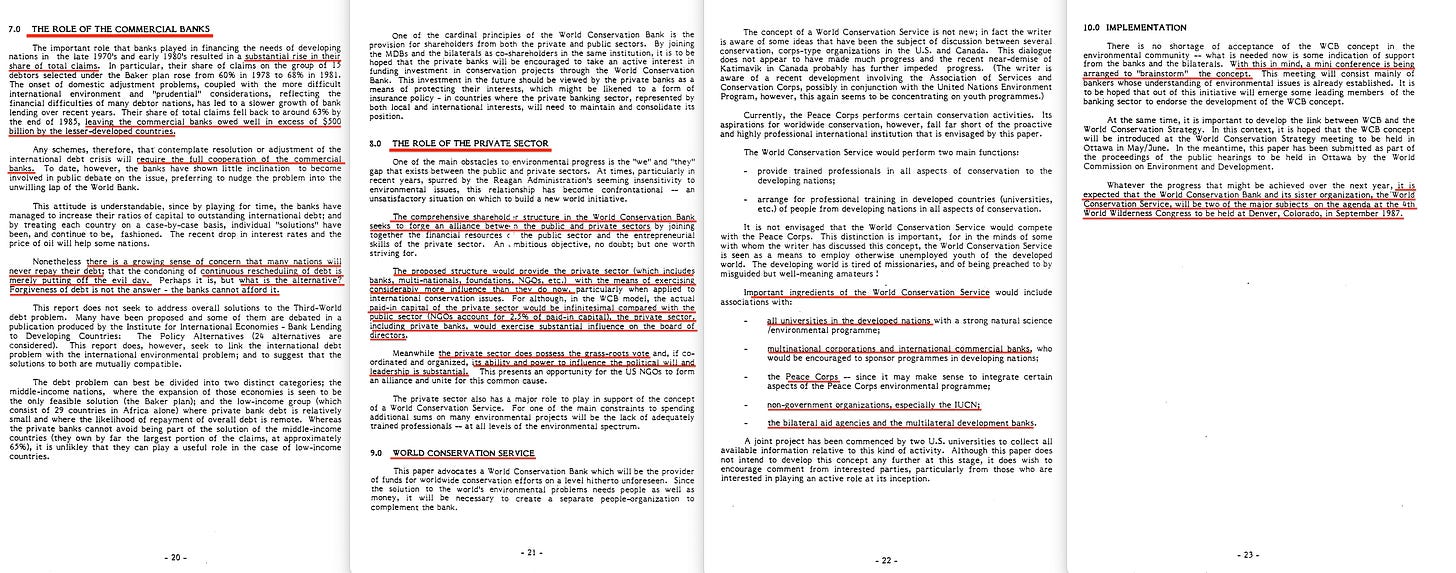

Sweatman’s 1986 paper outlined a mechanism where banks would transfer underperforming third-world debt to this new institution in exchange for long-term instruments, which would then be swapped with indebted nations in exchange for ownership or long-term leases of natural assets. The paper called for ‘the natural resource base and services of the ecosystem’ to be ‘included in the calculations of costs and benefit — to produce an environmental rate of return’.

That phrase is the conceptual foundation for everything that followed: carbon credits, ecosystem services, natural capital accounting, ESG metrics.

At the 4th World Wilderness Congress in Colorado in September 1987, David Rockefeller and Edmund de Rothschild joined Sweatman in formally proposing the World Conservation Bank. A Chicago Tribune article12 reported that ‘at sessions attended by Rockefeller, Rothschild and other major world figures, Sweatman advocated setting up a ‘World Conservation Bank’ to make such deals’.

The first debt-for-nature swap was executed in Bolivia that same year13.

The Banking Crisis Nobody Mentions

Sweatman’s 1986 paper14 contained a revealing detail: commercial banks were owed ‘well in excess of $500 billion by the lesser-developed countries’, while primary capital for the entire US banking system was around $150 billion.

Even a 30% loss on this debt would have caused total Wall Street failure.

The World Conservation Bank proposal offered a solution. Banks could transfer underperforming debt to the new institution, receiving long-term instruments in exchange. Tax credits for losses would sweeten the deal. The third world debt crisis would be resolved, and in exchange, debtor nations would hand over long-term leases on natural assets.

The mechanism solved two problems at once: bailing out the banking sector while acquiring control over natural resources — without requiring democratic approval in any country.

The Common Ancestor

The World Conservation Bank became the Global Environment Facility15, established in 1991. The WILD Foundation confirms16: ‘Through Michael Sweatman, Edmund de Rothschild, and others, the 1987 WWC proposed the establishment of a World Conservation Bank, which eventually led to the $1.1 billion US dollar Global Environment Fund of the World Bank’.

At the 1992 Rio Earth Summit17, both the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) named the GEF as their financing mechanism. The UNFCCC founding document18 states the GEF ‘shall be the international entity entrusted with the operation of the financial mechanism’. The CBD states the GEF ‘shall be the institutional structure’19.

The World Conservation Bank was positioned as the financial backbone of the entire environmental governance architecture before either treaty existed.

How the Money Works

The GEF structures ‘blended finance’ deals bearing uncomfortable resemblance to the collateralised debt obligations that caused the 2008 financial crisis, but now with an even bigger sucker accepting the role of the sitting duck. Private investors take senior equity positions with guaranteed returns, while public money takes junior positions bearing most of the risk.

According to the Paulson Institute’s figures20, public sources account for over 90% of biodiversity financing. The private sector contributes roughly 8% — but that 8% is structured to receive guaranteed returns while the public absorbs losses. In default, private senior equity holders could hypothetically take ownership of the underlying collateral: the land, the forests, the ‘ecosystem services’.

In 2010, Edmond de Rothschild launched Moringa21, the first blended finance funds focused on agroforestry. The fund’s whitepaper states it ‘became one of the pioneers of blended finance’. The same network that proposed the World Conservation Bank in 1987 ran the trial balloon for monetising natural assets.

The assets being monetised include UNESCO Biosphere Reserves22 — lands pledged by nations for conservation, now structured into financial products generating carbon credits, water rights, and timber concessions.

1989: The Launch

When the G7 met in Paris in July 1989, the same document that created global financial surveillance also endorsed debt-for-nature swaps, endorsed the IPCC, and called for what became the UNFCCC. Two years later, the World Conservation Bank proposal became the Global Environment Facility, housed at the World Bank23.

The financial surveillance rail and the environmental governance rail were designed together by overlapping networks as components of a coherent system. Both use similar mechanisms: standard-setting bodies, compliance frameworks, conditionality, and the ability to discipline non-compliant actors through access to markets and finance.

At the 1987 congress, ecologist Raymond Dasmann offered a warning24: ‘Beware of bankers bearing gifts’.

How It Grew

FATF was allowed to expand without anyone voting on the change. In 1989 it focused on drug money. After September 11, 2001, it added terrorist financing25. In 2012, it added weapons proliferation26. In 2019, it added environmental crime27.

Each expansion followed the same pattern: a crisis was identified, technical changes were made to the recommendations, and national regulators implemented them. No parliament debated whether FATF should cover environmental crime.

With environmental crime now in FATF’s remit, the two rails connect directly. The same infrastructure that freezes a terrorist’s assets can freeze the assets of anyone deemed to have committed an environmental offence — with the offences defined by technical bodies, implemented by regulators, and enforced by algorithms, none of it subject to democratic vote. And because the mandate is open-ended, there is no limit to what else might be added.

The environmental provisions in that original 1989 document now make more sense — the infrastructure was always intended to serve multiple purposes, and the machinery can be activated for whatever purpose those who control it decide.

What Just Happened

This week, the UK announced it will use the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018 to detain tankers suspected of carrying Russian oil28. That law was built to implement FATF frameworks for financial surveillance29. Now it provides legal authority for military interdiction of ships at sea.

What began as drug money surveillance has expanded to terrorist financing, weapons proliferation, environmental crime, and now physical seizure of vessels. The open-ended mandate that enabled this expansion echoes recommendations 3.2 and 3.3 from the 1968 UNESCO Biosphere Conference30, which defined key terms in their ‘broadest connotation’ — deliberately vague language that eventually developed into One Health.

The trick is old. Write it loose, interpret it later.

The Question

The vision Edmund de Rothschild articulated in 1977 — how the earth as a whole should be ‘administered’ — has been progressively implemented through institutions that bypass democratic accountability entirely. FATF was never approved by any parliament. The Global Environment Facility grew from proposals developed in private congresses and now structures deals benefiting private investors at public expense. Both enforce compliance through economic pressure that countries cannot resist, and both can expand their scope indefinitely without returning to any electorate.

Who gave these institutions authority over the economic lives of billions of people?

Nobody did.

They simply started exercising that authority, and nobody stopped them. The machinery is built. Natural Asset Companies — vehicles designed to float ‘ecosystem service’ leases such as carbon credits on stock exchanges — have already been proposed. The SEC rejected the first application in 2024.

They will try again.

But this time they will be backed by international enforcement mechanisms that secure investor rights even if host nations default. The collateral doesn’t revert to the people. It transfers to the creditors.

The ‘hypothetical’ was no more. That was decided in Cape Town.

And you were predictably never given an opportunity to vote on it.

Find me on Telegram: https://t.me/escapekey

Find me on Gettr: https://gettr.com/user/escapekey

Bitcoin 33ZTTSBND1Pv3YCFUk2NpkCEQmNFopxj5C

Ethereum 0x1fe599E8b580bab6DDD9Fa502CcE3330d033c63c

Well researched, with sources. Holy Yikes, it’s one of those moments “ I did not know that “

Thx for sharing. Not sure how we extricate ourselves.

I can’t believe the silence here …. It’s so loud .