Of the members of the Invisible College, almost none are as elusive than Paul Carus. In fact, few appear to even know who he is.

Yet — much like similarly critically underreported Julius Wolf, Leonard S Woolf and Alexander Bogdanov — he played a pivotal role in establishing our current predicament.

In the late 19th century Paul Carus (1852–1919) launched a visionary project of ethical universalism at the 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago. A German-American philosopher and editor, Carus argued that religion’s enduring core was morality, not dogma:

Religion is indestructible, because it is that innermost conviction of man which regulates his conduct. Religion gives us the bread of life. As long as men cannot live without morality, so long religion will be needful to mankind.

Religion, to Carus, is a channel of moral conduct. Yet Carus did not have a traditional view upon God himself:

God is to me, as he always has been to the mass of mankind, an idea of moral import. God is the authority of the moral ought

Ergo, in Carus’s view, God was no supernatural person but the invisible authority or architecture enforcing ethical conduct1. And as to what said morality relate:

By religious truth we understand all such reliable statements of fact or doctrines, be they perfect or imperfect, as have a direct bearing upon our moral conduct. Statements of fact, the application of which can be formulated in such rules as ‘Thou shalt not lie,’ ‘Thou shalt not steal,’ ‘Thou shalt not envy nor hate,’ are religious.

Scientific truths and moral truths, accordingly, are not separate and distinct spheres. A truth becomes scientific by its form and method of statement, but it is religious by its substance or content

Religious truths are those which influence moral conduct, and what’s morally true cannot be separated from scientific truths, as:

Science, i.e., genuine science, is not an undertaking of human frailty. Science is divine; science is a revelation of God. Through science God communicates with us. In science he speaks to us. Science gives us information concerning the truth; and the truth reveals his will.

Science is a reflection of religion, and religion is the hidden structure of science.

Carus in 1893 also published The Religion of Science2, which further aligns with the above. First, he establishes that religion is the conductor of man, while science is the search for truth. And, logically, the Religion of Science then relates to conduct of man being regulated by scientific discovery. In fact:

(3) That which is good and that which is evil must be found out by scientific investigation.

Which, essentially, then becomes a matter of ethics, but further:

(4) The religion of science accepts the verdicts of science

Science, in essence, is authoritative. As for truth — that comes down to a correct statemnt of facts, and we as humans can only accept it and live our lives accordingly.

As for the ethical aspects:

The religion of science rejects the ethics of pleasure and accepts the ethics of duty. The authority of conduct is an objective power in the world, a true reality which cares little about our sentiments. We cannot rely upon our sentiments, our desire for pleasure, our pursuit of happiness, for a correct determination of our duty.

It’s all starting to come across fairly collectivist, and what comes next only strengthens that impression:

… the ethical problem proposes the question, What is our duty? And our duty remains our duty whether it pleases us or not

But what is said duty?

Happiness of which men speak so much and which is often so eagerly sought in a wild pursuit, does not at all play an important part in the real world of facts. Nor does it lie in the direction toward which our desires impel us. Happiness is a mere subjective accompaniment in life which is of a relative nature… Duty requires us to aspire forward on the road of progress. But while our pains are constantly lessened and our various wants are more and more gratified, the average happiness does not increase.

Our duty, thus, relates to raising the average level of happiness, and not our own.

We have to grow and to advance, and our happiness is only an incidental feature in the fate of our lives. In considering the duties of life, we should not and we cannot inquire whether our obedience to duty will increase or decrease happiness.

And not only is our own happines irrelevant, we shouldn’t even challenge the ethical duties we’re assigned. Trust science, right?

Finally, on the question of what truth relates to:

Truth is a correct statement of facts ; not of single facts, but of facts in their connection with the totality of other facts... Truth, accordingly, is a description of existence under the aspect of eternity. We have to view facts so as to discover in them that which is permanent.

Truth, cosequently, relates to facts when viewed through the lens of eternity. It is, in other words, a perspective on facts, and not the facts themselves.

So that naturally begs the question — whose perspective?

Now, let’s return briefly to the earlier point:

There are not two antagonistic truths, one religious, the other scientific. There is but one truth, which is to be discovered by scientific methods and applied in our religious life.

If science discovers the truth—and is the final authority—and religion functions as the channel through which that truth governs conduct, then ethics becomes the mediating layer between the two.

Put differently: ethics is the collectively-subjective medium through which science and religion communicate. It is the mechanism by which scientific knowledge is converted into moral obligation.

Human conduct, then, is regulated through this ethical interface. And if this interface is meant to govern not just individuals but mankind as a whole, then we are no longer talking about personal morality—we are now searching for a global ethic.

And that, of course, is exactly where Carus leads us. We'll return to that in a moment. But consider carefully what Carus is actually doing here: he is promoting scientific socialism—framed from a religious perspective.

Paul Carus’s The Ethical Problem3 (1890) builds directly on the core thesis of The Religion of Science—but deepens it by framing ethics as the ultimate unifying discipline, superseding both theology and metaphysics, and forming the foundation for a rational, universal moral order.

If the dogmas of the churches have for some reason become unsuitable as a basis of ethics, and I believe that they have indeed become so, the churches cannot simply ignore them, they will have to revise them, and the revision will have to be made with special reference to their ethical importance.

In other words: Christianity must change. Carus says so explicitly. And that’s particularly striking given he wrote this in 1890, just one year before Rerum Novarum (1891)4—the Catholic Church’s inaugural attempt to reconcile its theology with the demands of modern industrial society. That encyclical initiated the long process of infusing social justice and worker-centric ethics into Vatican doctrine, while Carus was already calling for a complete ethical reconstruction of religion along scientific lines.

But this alignment is hardly surprising, given the broader intellectual current Carus engaged with:

An important sign of the times, proving the great prominence of the ethical movement, is the foundation of the Societies for Ethical Culture... The Open Court being founded to afford a place for the discussion of philosophical and ethical subjects with the purpose in view of establishing ethics and religion upon a scientific basis, has devoted considerable space to the publication and examination of the views brought forward by leaders of the Societies for Ethical Culture.

As editor of The Open Court, Carus didn’t merely observe this movement—he actively supported and helped shape it. His journal became a platform for promoting the ideas of Felix Adler5 and the Ethical Culture6 movement7, both of which sought to ground moral life not in revelation or tradition, but in organised humanism.

Incidentally, Paul Carus — who just by coincidence was a freemason — chaired the 1893 Parliament on the Worlds Religions8, and contributed to a panel titled ‘Is Christianity losing ground’ — an event to which Felix Adler, founder of the Ethical Culture movement, contributed as well.

But there’s a particularly revealing inclusion in that book:

The following three lectures delineate a system of ethics which is based upon a unitary conception of the world. It takes exception to the vagueness of The Ethical Record, whose ethics as a matter of principle has no foundation; and it attempts to settle the dispute between Intuitionalists and Utilitarians.

So not only is this a unitary, even universal, moral framework—which naturally suggests a global ethic—but it also proposes to mediate between intuitionist and utilitarian positions.

A reconciliation of opposites. A third way? Or perhaps more precisely: a meta-ethical synthesis—one that renders old categories obsolete by placing ethics on a new, scientific footing.

Henry Sidgwick is then placed with the former9, while John Stuart Mill defines utalitarianism as:

The creed which accepts as the foundation of morals, Utility. or the Greatest Happiness Principle, holds that actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness, wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness.

Herbert Spencer10 is then listed as a prominent Utilitarian—a classification that’s debatable, but beyond the scope of this post. What matters more is that his ethical views are closely aligned with those of TH Huxley, whose 1893 Romanes Lecture decisively placed evolutionary ethics on the intellectual map11.

Paul Carus, in The Gospel of Buddha12, advocated replacing sectarian faiths with a single, rational, scientific religion — essentially a universal moral faith grounded in reason. This was more than an interfaith dialogue13; it marked the emergence of a movement toward ethical convergence — a fusion of science and spirituality aimed at establishing a shared moral order. Carus sought to distill ‘ancient guidelines for human behavior’ into a scientifically verifiable morality, capable of transcending cultural boundaries. For him, morality was a natural law—objective, binding, and discoverable through science—which even religion must acknowledge.

Consequently, in Carus’s framework, science discovers truth, religion must acknowledge it, and the common language binding them is ethics. And it is through this shared ethical grammar that a universal moral order becomes conceivable.

And it is precisely this grammar that Felix Adler would deploy to anchor morality within cultural institutions themselves. And that leads not only to Bogdanov’s Proletkult, but also Hermann Cohen’s System of Ethics14.

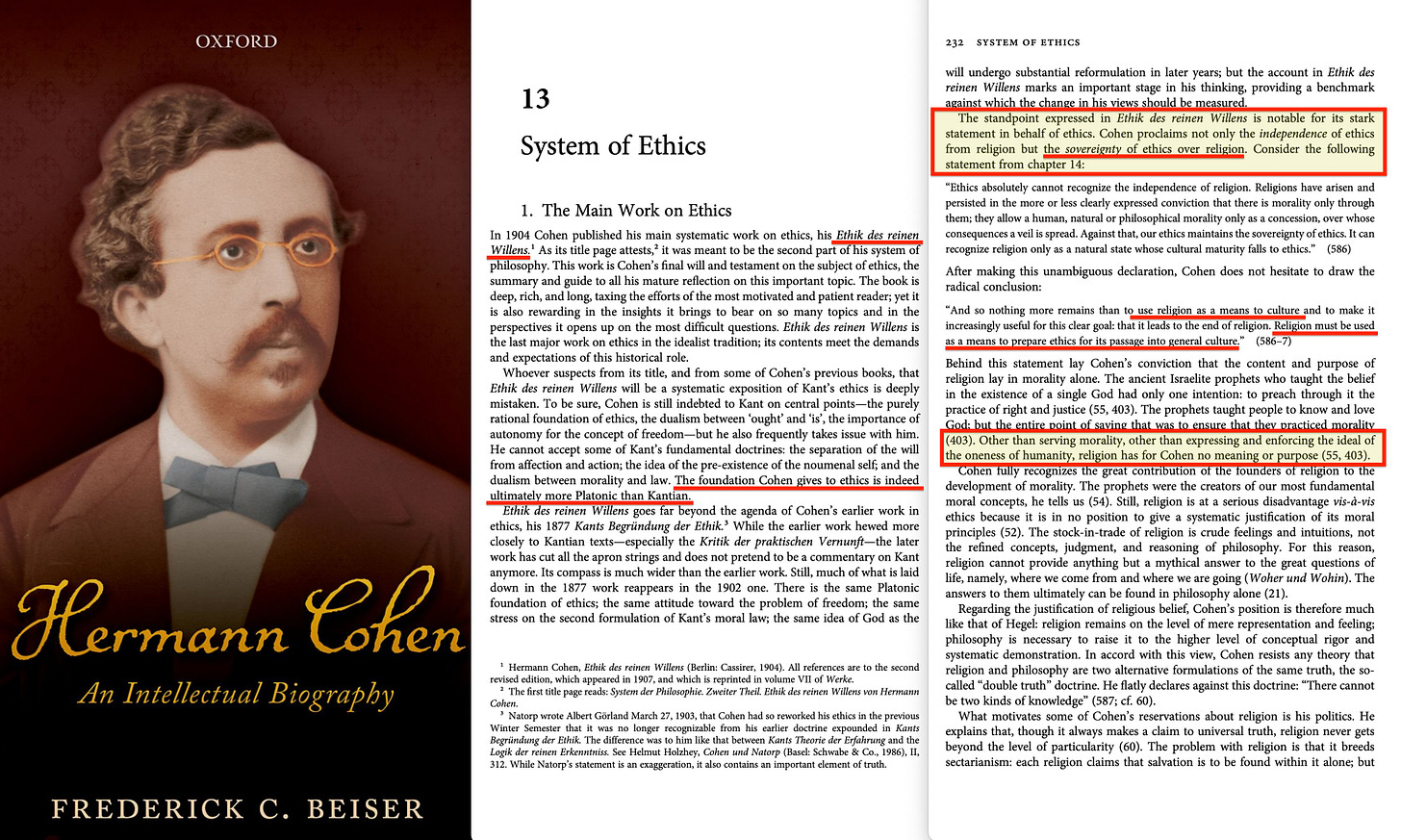

Parallel to Carus, Neo-Kantian philosopher Hermann Cohen15 (1842–1918) developed a universal moral framework grounded in pure reason. Synthesising Kantian ethics with Jewish tradition and democratic socialism, Cohen insisted that ethical obligation is rational—a categorical imperative binding on all humanity.

Not only did Cohen argue that monotheism itself introduced the idea of universal ethics, but he claimed that Judaism offered the world its first model of a universalist morality, since monotheism implies objective, binding moral law for everyone. In this way, Cohen anchored global ethics in both reason and religion, laying early foundations for what would become the modern project of global ethics—moral duties that cross cultures and history.

Yet Cohen did not view religion in its traditional form as essential. Rather, he saw it as a useful channel:

And so nothing more remains than to use religion as a means to culture and to make it increasingly useful for this clear goal: that it leads to the end of religion. Religion must be used as a means to prepare ethics for its passage into general culture.

Cohen’s rational moral project thus fits seamlessly with both Carus’s ethical universalism and Adler’s cultural institutionalism — all three advocating a moral order where religion is subordinated to ethics, and ethics is universalised through reason and culture.

Jacques Maritain (1882–1973), a French Catholic philosopher, further developed this universalist impulse. Maritain’s Integral Humanism16 blended Catholic faith with liberal democracy and human rights. He insisted that Christian spirituality calls for engagement in culture, not withdrawal – an ethos later embedded in the Second Vatican Council’s teachings. Maritain was close to Pope John XXIII and influenced Gaudium et Spes17, the constitution which speaks of human rights, social justice and the Church’s dialogue with the modern world.

In short, Maritain helped steer Catholic social teaching toward a global humanism18 in which every person’s inherent dignity and rights are the ethical baseline.

At Vatican II, Maritain’s ‘third way’ found sympathy with several theologians. Henri de Lubac19 emphasised essential unity, implying that ethics and faith cannot be separated. At the Council and in his later writings, de Lubac consistently pointed to a ‘holistic’ vision: love, beauty and the body are all part of God’s plan.

Yet not all Vatican II voices were unreservedly optimistic about the wholesale secularisation of ethics. Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI), would later warn against reducing ethics to technocratic management. In his view, the attempt to detach moral reasoning from theological foundations risked producing a world where truth became subjective and ethics merely an instrument of control.

The flip side to Ratzinger’s argument was Liberation Theology20, which he explicitly criticised for its Marxist underpinnings, singling out theologians like Leonardo Boff for subordinating the Gospel to the logic of class struggle. Boff envisioned a Christianity rooted in political transformation and committed to the liberation of the poor, but Ratzinger cautioned that this vision risked collapsing the transcendent dimension of faith into historical materialism. In his view, Liberation Theology too easily sacrificed spiritual truth to ideological activism, reducing the Church to a political agent and the Gospel to a social program.

For Ratzinger, ethics divorced from revelation becomes malleable — it can be co-opted by technocratic systems or political regimes. In contrast to Boff’s vision of ecclesial base communities challenging capitalism, Ratzinger insisted that true liberation must begin with the liberation from sin — rooted in divine truth, not historical materialism.

Thus, in contrast to the ethical convergence promoted by Carus, Adler, and Cohen — and the radical politicisation of ethics by Boff — Ratzinger called for ethics to remain accountable to something beyond human consensus or systems logic.

And yet, Ratzinger was also the first pope to speak positively of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, whose evolutionary theology envisioned humanity converging toward an ultimate ‘Omega Point’ — a kind of collective spiritual consummation.

Another familiar face present at the Second Vatican Council was Hans Küng, who would later organise the 1993 Declaration Toward a Global Ethic21 at the centenary of the 1893 Parliament of Religions22.

Küng’s Weltethos23 project explicitly called on all religions to affirm a set of shared ethical commitments — a direct intellectual descendent of Carus’s rational universalism, now rearticulated as a moral foundation for global solidarity. But Küng didn’t stop with religion. By 1999, he expanded the appeal to include ‘our guiding institutions’, calling for the ethical reformation of politics, business, science, and media24.

And this momentum was soon institutionalised beyond Blair: in 2000, the Earth Charter reframed this ethical convergence as a Planetary Ethic, marking the synthesis of interfaith universalism, and environmental moral governance.

Universalist currents have also shaped modern political theologies. One major strand — broadly aligned with Vatican II's social teachings — emphasises collective moral responsibility and justice. Latin American liberation theologians such as Gustavo Gutiérrez and Leonardo Boff argued that authentic faith demands a ‘preferential option for the poor’. To them, religion is not merely a personal message of salvation, but a mandate for societal transformation.

Liberation theology25 often aligns with leftist politics, advocating social reform, economic redistribution, and critiques of imperialism. It interprets structural injustice as ‘systemic sin,’ and frames group ethics — such as wealth redistribution, workers’ rights, and anti-colonial struggle — as religious obligations. In short, it leans quite heavily toward Marxist frameworks, and not without reason.

By contrast, a new American theology emerged on the right flank of contemporary politics: the Prosperity Gospel26. Televangelists like Paula White champion word of faith doctrines — essentially equating Christian blessing with material success. White, a spiritual advisor to Donald Trump27, is explicitly described as a proponent of prosperity theology, a movement that teaches individual faith and donations literally yield personal profit.

Thus, prosperity theology appeals with a hyper-individualist, market-driven ethic — placing the free market as a divine path to blessing, thus standing as the mirror-opposite of liberation theology’s ethos, where ethics means the right to succeed, not the duty to share.

These two currents — social-justice religion on one side, prosperity-focused religion on the other — define much of today’s faith-based political discourse in the United States. Liberation theology aligns roughly with Democratic politics (as seen in Biden’s Catholic social teaching), while prosperity theology aligns with the Republican right (exemplified by Trump’s alliance with Paula White). Yet, paradoxically, both can be traced back to the same universalist impulse. Each claims a global rationale: the left appeals to solidarity and justice, the right to a pseudo-divinely sanctioned capitalism.

What both lack is a shared moral substrate — a way to mediate their opposing visions through a hegelian dialectic. And that common denominator is finance.

What is needed is a synthesis, and that arrived through the concept of a moral economy.

What is needed is ‘Inclusive Capitalism’.

Since the 2010s, business and policy leaders have embraced ‘Inclusive Capitalism’ as a way to reconcile personal prosperity with social responsibility. This movement urges that capitalism be steered by metrics of broader human welfare, not profit alone28. Practically, this means embracing ESG criteria, the UN Sustainable Development Goals, and digital IDs and CBDCs — to embed moral aims into markets.

For example, in 2018 the Coalition for Inclusive Capitalism and EY launched the Embankment Project for Inclusive Capitalism (EPIC): a forum where 30 global companies (representing ~$30 trillion AUM) agreed to develop new metrics of value29. They recognised that a firm’s social value – in employee well-being, innovation, environmental stewardship – must be measured alongside quarterly earnings. In effect, Inclusive Capitalism proposes a global ethical accounting system. Corporations score high on ESG reports and SDG-aligned goals, and investors use these scores to allocate capital. Entire funds (like the Predistribution Initiative30) now focus on ESG and impact investment to ‘share more wealth and influence with workers and communities’, with politicians openly talking about tying tax or subsidy regimes to compliance with these new metrics and measures.

These systems cast morality in numbers. One initiative (the Taskforce on Inequality-related Financial Disclosures31) has mobilised over 100 organisations to report on how companies’ practices affect social equity, while pensions and asset managers are pushing for standardised ‘just transition’ metrics. Even in law, proposals circulate to require digital IDs that connect an individual’s social credit (charitable acts, volunteering, carbon footprint) to access to finance or benefits. While most of this is marketed as accountability, the effect is a computational moral economy: virtue is tracked, scored, and made transparent across borders.

At this point the parallels to authoritarian ‘social credit’ are easily noted. ESG frameworks can become de facto compliance grids: failing a human-rights audit could mean investor divestment or legal limits. Technology amplifies this: big data, blockchain IDs, and central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) offer tools to log every transaction and behavior. Some worry we are moving toward an ‘algorithmic gospel’ where righteousness is algorithmically evaluated. Indeed, cognitive scientists now discuss an innately programmed ‘universal moral grammar’ – suggesting that our sense of fairness might one day be formalised into code32.

We already see early signs: companies like Meta33 and Apple34 integrate ‘sustainability scores’ into products; governments consider linking tax privileges to personal carbon budgets. The Pope’s encyclicals have even weighed in on this trend. Francis’s Laudato Si’ (2015) invoked an integral ecology – uniting care for the earth with care for the poor – and explicitly echoed the UN’s Earth Charter themes of universal responsibility and justice. And in 2023 Laudate Deum35 reiterated the urgent need for a ‘new reverence for life’ and solidarity in confronting the climate crisis. All of this institutional support reinforces the view that sustainability and equity metrics are the new moral imperatives.

A perhaps unexpected bridge between these trends comes from India. In 1965 Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya articulated an ‘Integral Humanism’36 influenced by Gandhian ideas. Upadhyaya saw human life as guided by four objectives: dharma (moral duty), artha (wealth), kama (desire), and moksha (spiritual liberation). Crucially, he placed dharma (ethical duty) as foundational and moksha (higher spiritual fulfillment) as ultimate. He criticised both socialism and capitalism for fixating only on artha and kama – material gain and pleasure – thus ignoring higher human needs. For Upadhyaya, a truly ‘integral’ society balances prosperity and virtue, blending individual aspiration with community ethics. His model — adopted by Hindu nationalist parties — promotes a holistic national unity where economic development serves cultural and moral ends.

Broadly speaking, Upadhyaya’s project and Inclusive Capitalism both portray an ethics system that merges individual success and social justice. Neither fully rejects markets, but both aim to steer them with higher goals. Both treat morality as structural rather than merely private or metaphysical: one through spiritual hierarchy of aims, the other through codified metrics.

Over the past 130 years, philosophers from Carus and Cohen to Maritain and Küng have incrementally built a universal ethical framework. Each added a layer – rationalism, transcendental Kantianism, integral humanism, and secular global ethics – that moved moral truth from the realm of faith into that of scientific reason and policy. Today, this synthesis manifests in policy proposals and corporate practice: human rights, ecological stewardship, and equity are increasingly treated as data points — SDG indicators, HDI indicators, Aichi targets — alongside profits. In effect, Paul Carus’s quest for a unifying Religion of Science has morphed into an all-encompassing Regime of Metrics, justified through the ethics of social justice and planetary stewardship.

Pope Francis continued the vision of Teilhard and de Lubac, and in Laudato Si’ called for a ‘new universal solidarity’ and a rethinking of what human progress means37. Yet he also warns that without a universal moral anchor, the language we create — SDG indicators, carbon credits, ESG ratings — can become ends in themselves, with Benedict XVI before him similarly cautioned that a purely technical outlook ‘lacks direction’. Even so, the trajectory is clear: the global order is increasingly being woven from indicator metrics and digital wallet, intended to track your every purchase, and consequently, your ethical standing in this new world they have carefully designed.

In practical terms, this means more of our lives — from banking to travel to job prospects — may well soon hinge on ‘ethical’ data profiles. Central banks discuss digital currencies; social programs pilot digital IDs; companies refine ‘moral scores’.

Whatever one thinks of this, it is the culmination of an original ‘ethical convergence’ project. The rational morality dreamed of by Carus and cultivated by Cohen and Küng is no longer just academic: it has become a global infrastructure. Virtue is quantified, solidarity systematised, and even salvation seems recast as compliance with an all-encompassing algorithmic gospel.

And whether you voted Republican or Democrat, the Omega Point was already pre-programmed into the Cosmic SatNav prior to the election.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The price of freedom is eternal vigilance. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.