The Invisible College

Baruch Spinoza’s Ethica1 (1677) planted the metaphysical seed of one of modernity’s most quietly radical visions: a universe governed by a single, immanent substance—Deus sive Natura (‘God or Nature’). In this system, everything that exists is a ‘mode’ of one fundamental substance, expressed through different attributes. One might liken it — in more contemporary programming terms — to a type-casting operation: the same underlying entity, rendered differently depending on the interface.

And with it came a conceptual framework capable of collapsing the boundaries between the material and the spiritual into a single, continuous order. Everything could, in principle, be resolved into expressions of the same underlying substance — differentiated only by the resolution at which one perceived it.

This was no mere speculation. It was the philosophical prototype of monism2: a worldview in which all phenomena — physical, mental, or spiritual — are ultimately expressions of a unified order. And in a world increasingly fractured by theological, national, and class-based tensions — amplified by crisis, real or not — that unity would become an irresistible ideal: scientific, spiritual, and political.

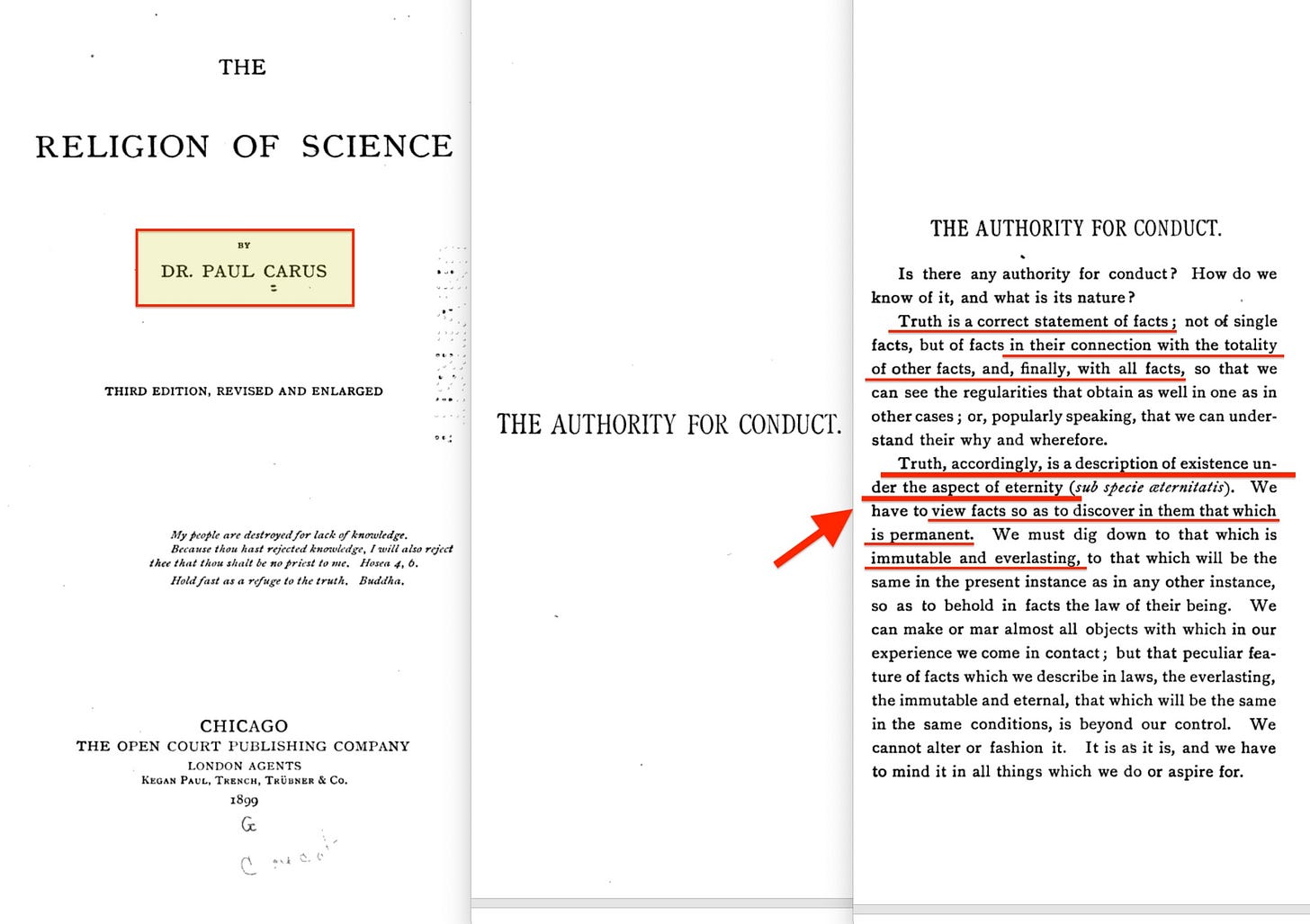

By the late 19th century, Paul Carus — a Freemason345, philosopher, and editor of The Open Court6 and The Monist78 — seized on Spinoza’s metaphysical unity and fused it with the materialist determinism of Marx. For Carus, this was not contradiction but synthesis: a ‘Religion of Science’ that transposed Spinoza’s divine Nature into a rational, morally-guided cosmos, with science assuming the role of priesthood. His The Religion of Science (1893)9, later expanded as The Religion of Science and the Science of Religion (1896), rejected all dualisms — mind and body, soul and atom, sacred and secular — as relics of ignorance. Nature was God, science was scripture, the moral imperative was universal, and truth was to be judged versus the eternal.

This synthesis — Spinoza’s religious monism joined with Marx’s material one — found institutional form at the 1893 Parliament of the World’s Religions10 which Carus chaired11. There, under the banner of interfaith dialogue12, the project of a global spiritual order guided by scientific reason began to take shape. Moral fraternity, natural law, and universal governance were no longer speculative ideals but emerging administrative possibilities.

In the East, a parallel project was taking shape. Alexander Bogdanov — Lenin’s rival13 and scientific organiser — developed a synthesis of Machian empiricism and Marxist materialism he called empiriomonism14. In this view, experience was neither purely spiritual nor purely mechanical — it was both. Psychic and physical phenomena were two expressions of the same unified experiential field. More importantly, this framework enabled a flexible, interpretive form of monism — aligned with Spinoza’s concept of substance and its expression through modes. Bogdanov would go on to develop Tektology15, which crystallised these principles into a general science of organisation, anticipating systems theory, cybernetics, and adaptive management by decades. In parallel, his Proletkult16 movement applied these ideas to cultural production, laying the groundwork for a form of scientific social engineering17.

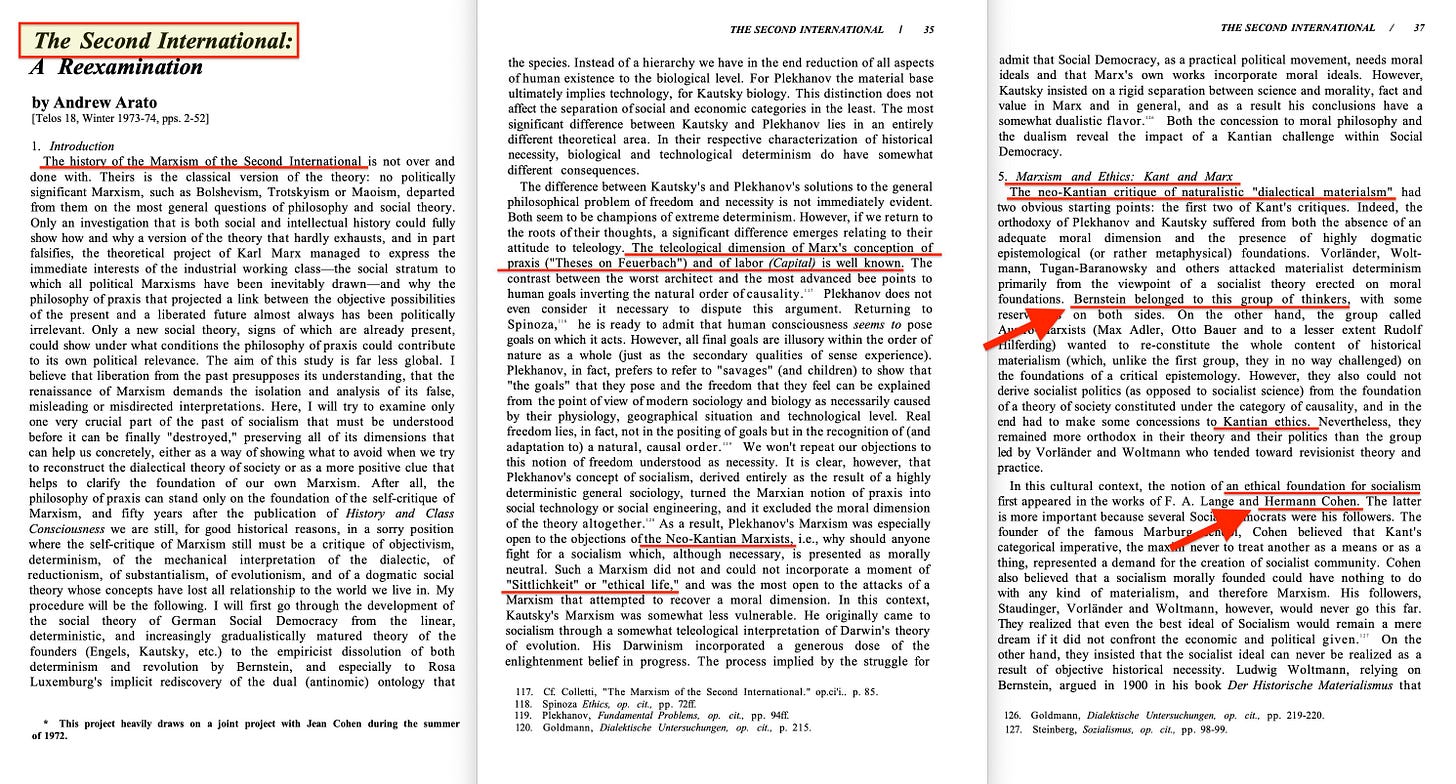

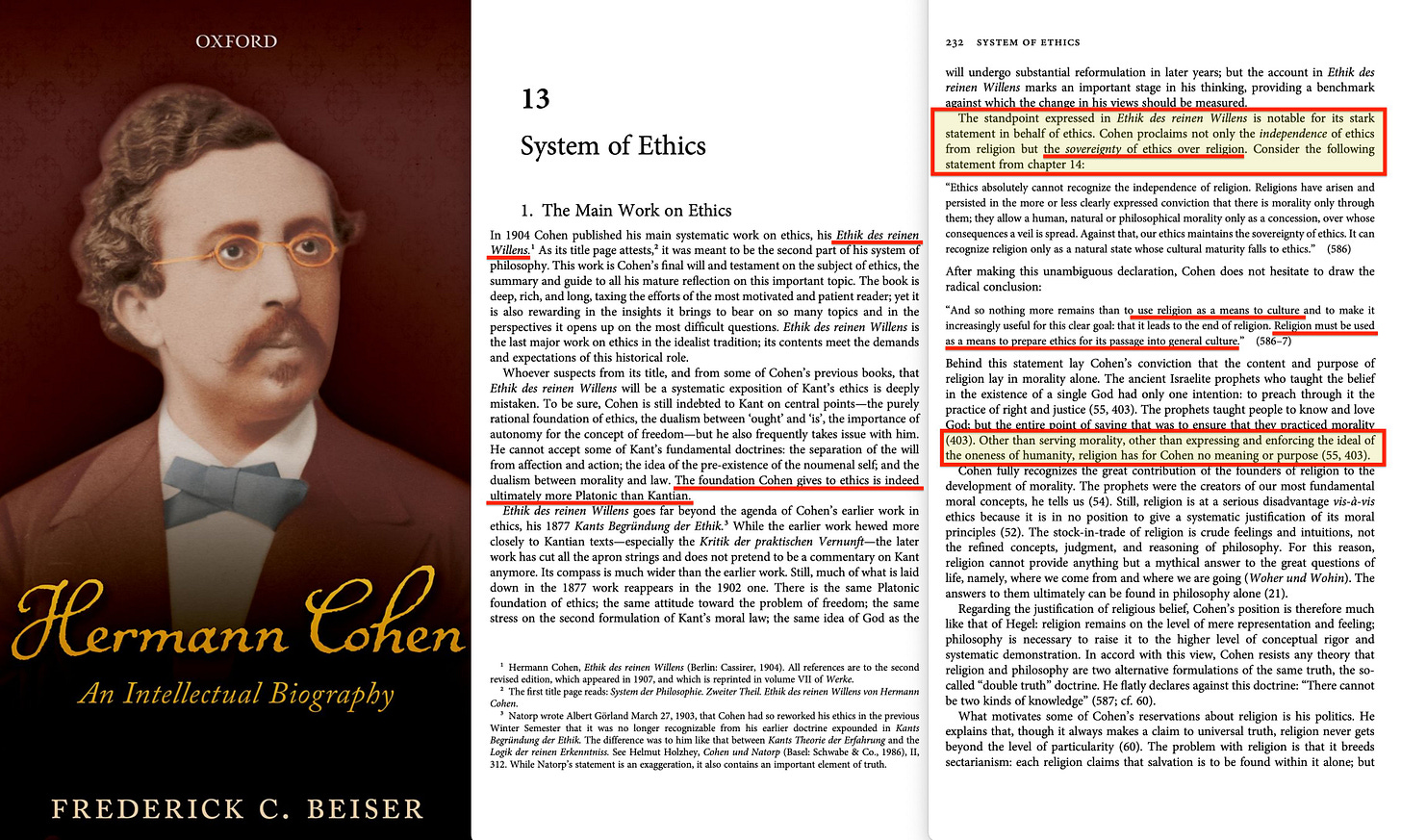

While Carus and Bogdanov articulated spiritual and methodological monisms, the Neo-Kantian Hermann Cohen advanced an ethical and legal one. Drawing from Kant’s categorical imperative18 and Aristotle’s golden mean19, Cohen argued that law must evolve in dialogue with moral reason — a living, rational process grounded in what he called ‘infinite judgment’20. Legal norms, like scientific hypotheses, must remain open to critical scrutiny and ethical refinement. Here, Socratic dialectic meets juridical process: law as unfolding moral order.

Meanwhile, the Platonic echo of monism reverberated through political theory. Leonard Woolf, drawing on guild socialism and the ideal of the philosopher-king, envisioned an international authority that would harmonise national sovereignty with supranational justice. His proposals for the League of Nations, enthusiastically backed by Alfred Zimmern, were not democratic in the liberal sense but hierarchical in the moral one: guided by enlightened expertise, not by populist will.

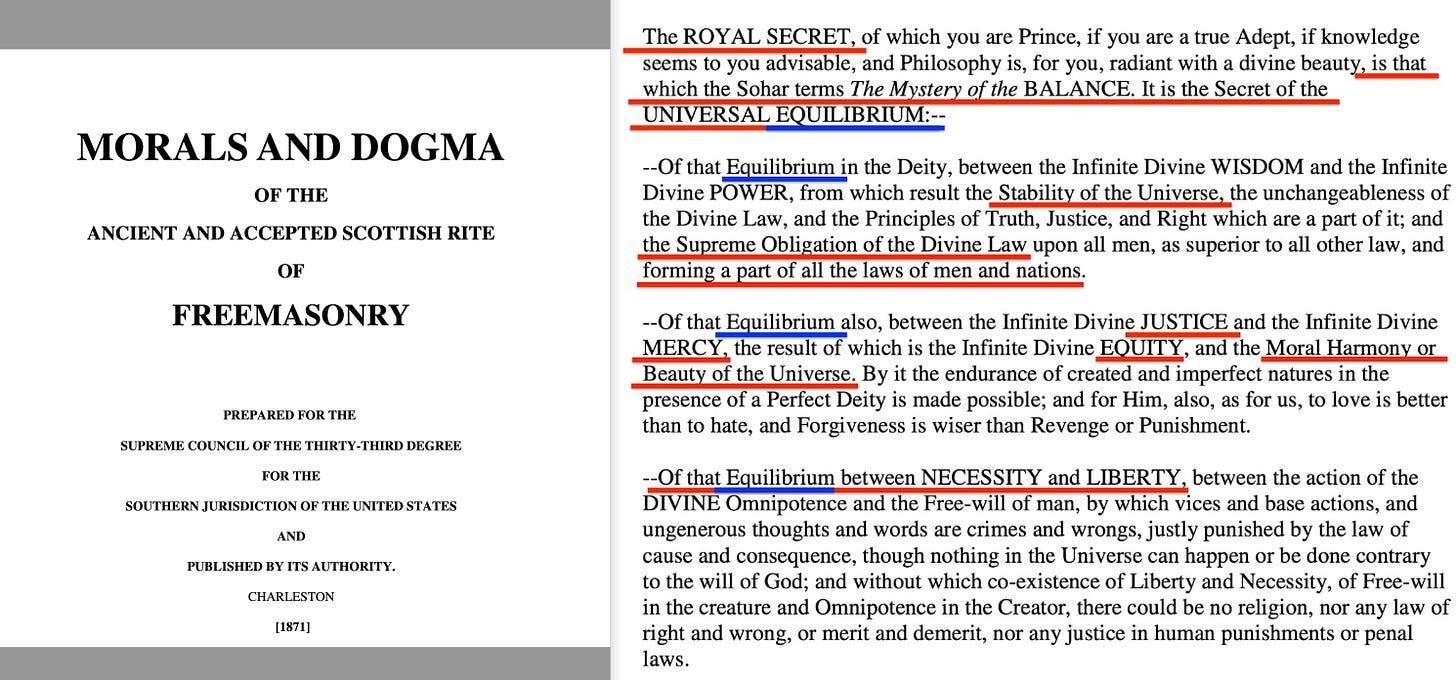

The esoteric domain was no exception. In Morals and Dogma (1871)21, Albert Pike presented the 33° Freemason not merely as a moral exemplar but as the guardian of universal equilibrium—an initiate who fuses material order, ethical virtue, and spiritual knowledge into a single cohesive worldview. The initiate does not govern the world, but orders it according to cosmic principles.

Finance, too, succumbed to the pull of unity. In 1892, Julius Wolf proposed a gold-based international clearing system modelled on the Universal Postal Union22. It was an attempt to consolidate global exchange under a single logic: a financial monism that would later be institutionalised in the gold-settlement mechanisms of the Bank for International Settlements.

Even evolutionary biology was enlisted. Thomas Henry Huxley — Darwin’s staunch defender, often called his ‘bulldog’23 — used his 1893 Romanes Lecture Evolution and Ethics24 to confront the chasm between natural selection and moral progress. Nature, he argued, is amoral; human civilisation, if it is to rise, must do so against evolution’s indifferent currents. This tension — between what is and what ought to be — reasserted the need for stewardship, not surrender.

In the 20th century, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin and Vladimir Vernadsky each offered complementary visions of totality. Teilhard’s ‘Omega Point’ fused Christian eschatology with evolutionary theory, casting the noosphere — the collective human mind — as a divine horizon of convergence. Vernadsky, by contrast, grounded this same noosphere in biogeochemical fact. The biosphere gives way to the noosphere not as metaphor but as scientific inevitability. Consciousness, like carbon, is planetary.

Across centuries and disciplines, these thinkers were not composing a single lineage so much as responding to a shared impulse, imagining a world governed as one. Their contributions form a typology of monist visions, each asserting a distinct mode of unification:

Spinoza: metaphysical monism — God or Nature as the one substance from which all things flow. In Spinoza’s system, the universe is not a dualistic battleground of spirit and matter, but a single, immanent order expressed through infinite attributes and finite modes. Mind and body, thought and extension, are simply different perspectives on the same underlying reality. Knowledge, for Spinoza, is not accumulation but alignment — a kind of spiritual perception through which one grasps the history of the whole. Freedom lies not in autonomy but in understanding the lawfulness of existence. This was more than metaphysics; it was a vision of total coherence — one that would become the blueprint for later projects of moral, political, and scientific unification.

Marx/Engels: historical-material monism — In The Communist Manifesto (1848), Marx and Engels redefined history as a single, dialectically unfolding process driven by material relations. Spirit, law, and ideology were not autonomous realms but epiphenomena — reflections of the economic base. In this monism, class conflict was not one variable among many, but the engine of history itself. By collapsing culture into material conditions, and politics into class struggle, Marxism offered a unified theory of social change: total, systemic, and inevitable. Though later adapted by revisionists like Bernstein, this original materialist core laid the foundation for all subsequent visions of historical rationality and world-historic planning.

Pike: esoteric monism — Within the Masonic tradition, Albert Pike portrayed the initiate — especially the 33° Freemason — as a steward of cosmic balance. This embodies a synthesis of moral virtue, metaphysical insight, and structural order. The world is not to be ruled arbitrarily, but ordered according to universal principles accessible only through spiritual initiation and disciplined ascent. In this framework, the Freemasonic conception of religion — rational, ethical, and ecumenical — is almost indistinguishable from Carus’s vision of scientific socialism: a religion of natural law, guided by reason, and oriented toward the moral perfection of humanity

Julius Wolf/BIS: monetary monism — The foundations of monetary monism were laid with the 1844 Bank Charter Act, which severed the power of private banks to issue currency and centralised control within the Bank of England. This marked the beginning of money as a closed, rule-bound system — abstracted from local discretion and governed by a singular logic of value. Nearly half a century later, Julius Wolf proposed an international gold-based clearinghouse, modelled on the Universal Postal Union, to bring this monetary order to the global scale. His proposal laid the groundwork for the gold-settlement mechanism later institutionalised by the Bank for International Settlements. In this architecture, unity is not just a principle but a structure: credit, debt, and currency flows all coordinated by a single financial logic, and unit of account.

Paul Carus: scientific monism — Carus synthesised Spinoza’s divine Nature with Marx’s material determinism, transforming metaphysical unity into a spiritual and ethical programme. His ‘Religion of Science’ reframed natural law as both sacred and rational — casting science as moral priesthood and progress as moral duty. This was not a rejection of religion, but its scientific reformulation: a pantheist ethic dressed in empirical robes. The result was a vision of human perfectibility guided by reason, a cosmopolitan moral order that closely mirrored the Freemasonic view of universal brotherhood — rational, ecumenical, and hierarchical in spirit.

T.H. Huxley: evolutionary monism — Known as ‘Darwin’s bulldog’ for his fierce defence of natural selection, Thomas Huxley nonetheless emerged as one of its most paradoxical critics. In his 1893 Romanes Lecture Evolution and Ethics, he argued that nature, while governed by law, is morally indifferent — and that human civilisation must construct an ethical order in defiance of it. Evolution, for Huxley, could explain the survival of species, but not the dignity of persons. His monism lay not in harmony but in conflict: one world, governed by one set of physical laws, which humanity must transcend through moral will. Stewardship, in this frame, is not a natural inheritance but a self-imposed duty — an act of conscious resistance to nature’s indifference. This ethical vision would echo through his descendants: Julian Huxley, the evolutionary biologist and founder of UNESCO, who embraced the managerial possibilities of human evolution; and Aldous Huxley, who rendered its dystopian shadow in Brave New World.

Eduard Bernstein: socio-economic monism — Bernstein’s revisionist Marxism rejected violent revolution in favour of evolutionary convergence — order, not upheaval. Drawing implicitly from the monetary logic of Julius Wolf’s gold-clearing scheme, Bernstein grounded socialism not in class struggle but in the rational coordination of production, finance, and ethics. His ‘ethical socialism’ envisioned a world unified by gradual reform, institutional compromise, and the technocratic pursuit of the common good. It provided the ideological basis for later public-private governance models, including Leonard Woolf and Alfred Zimmern’s supranational architecture: a managed harmony of capital and virtue.

Alexander Bogdanov: empiriomonism — Like Carus, Bogdanov drew from Spinoza’s metaphysical unity, but channelled it into an operational framework. His empiriomonism fused Machian epistemology with Marxist materialism, casting psychic and physical phenomena as interchangeable expressions of a single experiential field. Tektology later systematised this into a general science of organisation — a proto-cybernetic model of planned coherence across domains. Crucially, Bogdanov’s monism was adaptive: like Spinoza’s modes, social and technical forms could vary in structure while remaining expressions of a unified process. Where Eduard Bernstein envisioned ethical socialism as a path toward harmony through gradual reform, Bogdanov provided the methodological toolkit to make that vision actionable. Through Empiriomonism, Proletkult and Tektology, the common good could be scientifically engineered — not merely preached, but programmed.

Hermann Cohen: ethical-juridical monism — Reviving Kant through the lens of infinite judgment, Hermann Cohen proposed that law and morality are not separate domains but two expressions of the same rational process. Legal norms evolve through sustained moral scrutiny; justice is not handed down but reasoned upward, through a dialogical process rooted in Socratic inquiry. Drawing on Aristotle’s golden mean, Cohen envisioned ethical law not as rigid commandment but as a dynamic unfolding of balanced moral reason. In this, he aligned closely with Carus: both elevated ethics as the universal substrate beneath religion. But where Carus sought to rationalise religion into scientific morality, Cohen saw religion as secondary altogether — a cultural vessel for encoding and transmitting ethical insight over time. Religion, for Cohen, did not reveal moral truth — it carried it. Yet another useful tool added to Proletkult.

Leonard S Woolf/Zimmern: political-managerial monism — Building on Bernstein’s ethical socialism and the monetary logic underpinning international clearing systems, Leonard Woolf and Alfred Zimmern envisioned a supranational order where governance would be coordinated by experts across both public and private sectors. Their League of Nations proposal was not a federation of democracies but a technocratic architecture: guild socialism scaled to the international level, managed by those presumed to embody reason, virtue, and foresight. Inspired by Plato’s philosopher-kings and justified by the rhetoric of the common good, their model fused political legitimacy with managerial authority. Democracy was not abolished — it was embraced, and extended into a moral bureaucracy.

Technocracy: energy monism — Emerging in the early 20th century, the Technocracy movement proposed reorganising society not around politics or money, but around energy flows. Inspired by thermodynamics and industrial systems engineering, technocrats envisioned a post-market society governed by energy certificates and technical metrics — measuring human activity in joules rather than currency. This was monism by caloric calculus: a world managed through a single, measurable substance. Technocracy collapsed value into energy, and decision-making into optimisation. Though marginalised politically, its logic survived: in systems ecology, climate governance, planetary boundaries, and the emerging discourse of ‘carbon accounting’, the dream of a managed energy civilisation lives on.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin / Vladimir Vernadsky: spiritual-scientific monism — Teilhard’s Christian evolutionary vision and Vernadsky’s geochemical cosmology converge on a single organising principle: the noosphere, the sphere of human thought enveloping the Earth. For Teilhard, this was the teleological endpoint of evolution — the Omega Point — where consciousness ascends toward divine unity. For Vernadsky, it marked a scientific phase transition: the biosphere, shaped by life, giving way to a planet reshaped by thought. In both cases, spirit and matter, science and theology, converged into one unfolding planetary process. Their visions would be taken up by Julian Huxley, first Director-General of UNESCO and grandson of T.H. Huxley, who saw in the noosphere a mandate for directed evolution — humanity as both the product and the steward of planetary transformation. Through institutions like UNESCO, Teilhard’s mystical convergence was translated into managerial doctrine: the spiritual destiny of humankind reinterpreted as a technocratic programme of global coordination. Consciousness, like carbon, became planetary — and governable.

What binds these is not a shared doctrine but a shared project: to create — or to reveal — a universe in which law, ethics, spirit, and management are not separate domains, but coordinated expressions of... One World.

This is not merely intellectual history. Today’s cybernetic governance systems — those that promise climate control, health surveillance, AI ethics, and financial harmonisation — draw from the same metaphysical root. They speak in the language of unity, but operate as architectures of control.

Where once monism was a metaphysical vision — a way of interpreting the cosmos — it has become a managerial instrument. Kant provided the moral compass, Hegel the arc of development, and Cohen the juridical framework through which ethics could be institutionalised into law. Teilhard supplied the telos, Vernadsky the material substrate, and Julian Huxley the institutional translation. What began as a search for harmony has become a machinery for integration — abstract ideals rendered into operational systems.

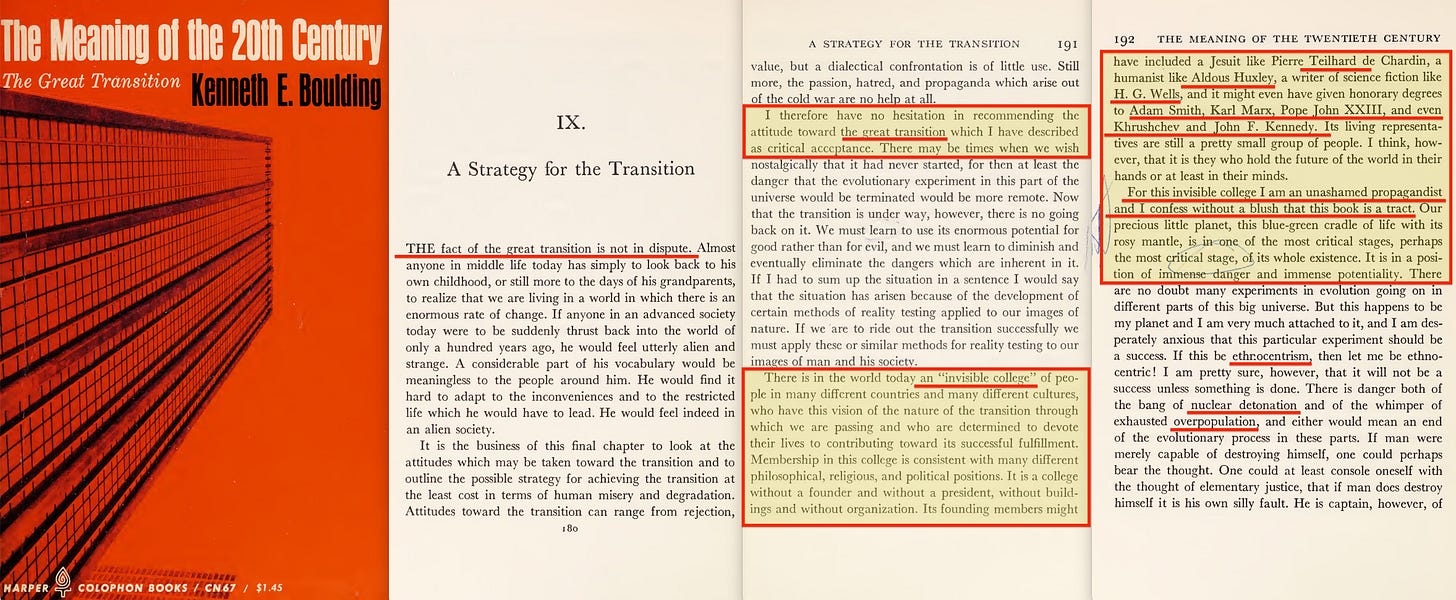

And yet, few of these figures — Wolf, Bogdanov, Carus, Cohen in particular — are remembered for what they truly were: architects of the operating system beneath modern life. Their legacies live not in popular memory but in institutional form: embedded in international finance, interfaith dialogue, systems theory, ethics committees, and supranational law. Perhaps this obscurity is no accident. As Kenneth Boulding wrote in The Meaning of the Twentieth Century, history is increasingly shaped not by emperors or parliaments, but by an ‘invisible college’ — a loosely networked elite of thinkers, planners, and administrators who steer civilisation through models, metrics, and metaphysical assumptions. Boulding himself was a key node in this process: his 1956 essay ‘The Skeleton of Science’ helped introduce Bogdanov’s Tektology into the emerging language of systems theory, while his 1966 paper ‘The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth’ transformed planetary stewardship into a managerial ideal. It is not hard to see in Carus, Cohen, Bogdanov, and Wolf the early initiates of this epistemic guild. They did not seize power; they designed the logic through which power now governs.

Monism, in this sense, is not just a metaphysical claim — it is a managerial perspective. It is the act of viewing the world through a particular mode, to use Spinoza’s term: a lens through which complexity is recast as coherence. Once this perspective is assumed, the world can be made to balance — not by negotiation, but by design. Over time, this logic was applied progressively: to finance, through central banking and clearing systems; to politics, through supranational governance; to law, through universal ethics; and to nature itself, through environmental regulation and planetary boundaries. What made all this possible was systems theory: the translation of metaphysical unity into operational architecture. And the custodians of this balancing act — the ones who decide which mode is applied, and how — are not elected officials, but the modern heirs of Plato’s philosopher-kings. Their role is not to debate truth, but to manage the structure of the whole.

And now, the entire architecture is visible. The Sustainable Development Goals offer the unified telos: a system of measurable virtue, aligning ethics, economics, and ecology into a matrix of global targets. Governance is no longer directional — it is procedural. The SDGs are not political ideals but cybernetic endpoints: calibrated indicators guiding planetary management under the banner of the ‘common good’. This system is coordinated not by national parliaments, but by a transnational infrastructure — Agenda 21 aligning global governance structure, and the BIS-IMF-World Bank nexus managing global finance. Post–gold standard, post-democratic, and post-political, this is monism operationalised: a single architecture to balance the world.

And yet, none of this is new. Behind the scientific veneer lies a classical architecture: Socrates’ ethic of inquiry, Plato’s philosopher-kings, Aristotle’s golden mean and virtue ethics. Their heirs no longer debate virtue in the agora — they model it, optimise it, and encode it. With adaptive management, cybernetic feedback, and AI-augmented governance, ethics is no longer argued but operationalised. Marx once imagined, in his Fragment on Machines25, that the development of productive forces would liberate humanity from toil. And so it has — but only for some. For most, the result is not freedom but a classless, post-political feudalism: a managed life under fully automated systems of compliance, nudged toward the common good. Above it all, a handful ascend — initiates of a new rational order — preparing to take their seats in the cockpit of Spaceship Earth as TH Huxley in 1893 annnounced that they should, governing not by persuasion, but by programme — Permanently.

The only question is… who would be that ship’s captain26?