For over a century, the architecture of global finance has been evolving quietly, deliberately, and almost invisibly. Its foundational pieces were laid not on the battlefield, but in committee rooms, banking halls, and treaty conferences. Today, we live under the rule of a system that no one voted for, but which governs nearly every aspect of national policy. It is a structure built not from soldiers and flags, but from central bank coordination, fiscal conditionality, and development finance. And at its core stands the technocratic triad: the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the World Bank.

Together, these institutions have come to fulfil the role envisioned in 1916 by Leonard Woolf in his seminal work International Government: an international apparatus operating above sovereign boundaries, enforcing order not through armies, but through interdependence and administration. His proposal, meant as a peaceful alternative to war, became the template for a technocratic system capable of dissolving sovereignty in the name of stability.

The BIS: Neutral Hub or Monetary Governor?

The BIS structure, at its core, operationalised a concept first described by Julius Wolf in 1892 — a mechanism for international financial clearing anchored in gold reserves, but abstracted into centralised administration. Under Wolf's model, the function of money was removed from the hands of sovereign states and redefined as a technical instrument subject to expert coordination. The BIS adopted this premise but took it a step further: by acting as a clearing house for central banks, it could lend gold or other reserve assets between member states—and charge interest for doing so.

This meant that the BIS effectively collected rent on assets it did not own — public gold, pooled via central banks, but ultimately belonging to the citizens of those countries. In this way, the BIS became a kind of meta-bank, able to profit from stabilising global imbalances while remaining entirely outside public accountability. It imposed discipline on sovereigns not by denying credit outright, but by conditioning access to international liquidity on compliance with monetary orthodoxy.

Founded in 1930, ostensibly to handle German reparations, the BIS quickly became the quiet apex of the world’s monetary order. It offered a facility for central banks to deposit gold, net claims, and draw advances against pooled reserves. This meant that instead of physically transferring gold between sovereigns, balance sheets could be adjusted through internal bookkeeping — a precursor to modern digital monetary coordination.

While this appeared to be a convenience, it created a powerful dependency: central banks became enmeshed in a transnational system, unable to act unilaterally without risking liquidity isolation or loss of reputation. Over time, the BIS expanded into policy-setting through Basel Accords, macroprudential oversight, and green finance through the NGFS. Member banks don’t merely cooperate; they converge.

The BIS has not been without controversy. During World War II, it was accused of facilitating gold transfers for the Nazi regime, including gold looted from occupied territories. More recently, critics have charged the BIS with advancing regulatory frameworks that disproportionately benefit large, globally integrated financial institutions, while reducing the policy space available to smaller or developing nations.

The IMF: From Liquidity Provider to Policy Enforcer

The IMF was founded in 1944 to ensure exchange rate stability and prevent beggar-thy-neighbour policies. But over time, it transformed into the fiscal disciplinarian of last resort. When a sovereign government finds itself unable to meet debt obligations or defend its currency, and when its central bank refuses (or is unable) to monetise the deficit, the state is forced to seek IMF assistance.

This typically occurs under two key conditions: either the nation's debt is denominated in a foreign currency (preventing monetisation without risking collapse), or its central bank is unwilling or unable to provide domestic liquidity — either due to legal constraints or because the BIS refuses to facilitate through existing swap or liquidity lines. In such cases, the IMF becomes the only option left, stepping in to enforce a prescribed set of reforms and restructure public finance.

IMF loans come with strings: structural adjustment programmes, fiscal reforms, cuts to subsidies, privatisations, and labour market deregulation. These conditions reflect a deep ideological bias toward neoliberal governance. The result is a reversal of democratic sovereignty: parliaments may vote on budgets, but the parameters are written in Washington.

One well-documented example is Argentina, which received dozens of IMF programmes throughout the late 20th century, culminating in the 2001 economic crisis. IMF demands for austerity, labour liberalisation, and budget cuts not only deepened the recession but sparked widespread protests and the collapse of several successive governments.

Another notable case is Jamaica in the 2010s, where IMF-led reforms included massive cuts to public services and the freezing of public-sector wages for several years. Though praised for improving debt metrics, these policies were linked to a rise in social inequality and declining public health infrastructure.

The World Bank: Bernstein’s Bank for the Common Good

If the BIS manages money and the IMF controls policy, the World Bank directs capital flows. Originally created to fund post-war reconstruction, it has since reinvented itself as a development institution. One of its most powerful tools is the use of blended finance constructs — where public or philanthropic capital is used to de-risk private investment. This arrangement is presented as a way to fund large-scale development projects in the name of the 'common good', but in practice it often transfers risk to taxpayers while allowing the private sector to extract profits with little accountability.

Private actors — often multinational corporations or investment firms — gain access to public-backed guarantees, subsidised rates, or concessional capital under the pretext of achieving Sustainable Development Goals. Should the project fail, the public absorbs the loss. If it succeeds, the profits are largely retained by the private participants. In this way, the World Bank acts less as a neutral development agency and more as a facilitator of public-private partnership structures that socialise risk and privatise reward.

But many of these projects are less about empowering local communities and more about enshrining global norms. Through mechanisms like debt-for-nature swaps, sovereign land is placed under permanent environmental restriction and, in some cases, pledged as collateral for financial agreements. Should the debtor nation default, the rights to manage or enforce restrictions on this land can be transferred to transnational custodians — often under the auspices of organisations such as UNESCO. In these arrangements, UNESCO Biosphere Reserves act as a kind of neutral trustee, institutionalising conservation obligations that effectively override domestic legislative processes, often managed or co-owned by international NGOs, philanthropic foundations, or special-purpose vehicles. The local state remains in name, but control has passed to a transnational network of 'stakeholders'.

For example, in 2016, the Seychelles restructured $21.6 million in sovereign debt through a debt-for-nature swap brokered by The Nature Conservancy and supported by the World Bank. In exchange, the government committed to protect 30% of its marine territory. While framed as a win for conservation, it effectively placed management of vast swathes of ocean under a foreign-administered trust.

Another World Bank controversy unfolded in Uganda, where the Bank funded a large infrastructure and energy project that, according to investigations by human rights organisations, led to mass displacement, land grabs, and rights violations. Despite formal safeguards, local communities were left with little recourse.

The Triad in Practice: A Self-Reinforcing System

The COVID-19 pandemic offered perhaps the clearest modern demonstration of the triad’s real-time coordination and institutional power. When governments locked down entire populations and halted economic activity, central banks stepped in to flood financial markets with liquidity. This action was not isolated—it was globally synchronised, with monetary authorities across the West coordinating their moves through the BIS. These emergency measures stabilised capital markets and funded massive public spending, but they also served to entrench a system of managed coordination between fiscal and monetary institutions.

The BIS facilitated the crisis response not just technically, but ideologically — normalising the merger of state and central bank mandates, encouraging fiscal expansion where aligned with climate and social objectives, and laying groundwork for even deeper integration. As national deficits soared, it was the IMF that provided support to the most distressed, demanding structural reforms in exchange. And as the recovery began, the World Bank scaled up climate-linked finance, channelling public-private capital into SDG-aligned infrastructure and conservation schemes.

COVID was not just a health crisis. It was a stress test for global governance, and it showed how seamlessly this triad could take control in an emergency. It also served as a template for future crisis management — particularly the anticipated global climate crisis. With climate framed as an existential, transboundary emergency, the triad is already laying the groundwork for similar coordination: central banks integrating climate risk into monetary frameworks, the IMF preparing climate-linked lending and carbon taxation models, and the World Bank scaling climate resilience investments via blended finance. Just as COVID justified extraordinary monetary-fiscal alignment, the climate emergency will justify the same — only permanently, dressed in the verbiage of the meta-crisis.

This triad operates as a self-perpetuating machine:

The BIS sets the monetary boundaries.

The IMF steps in when those boundaries are breached.

The World Bank offers capital, but only along preapproved lines.

And when crises hit — pandemics, debt defaults, climate shocks — the response is coordinated. Nations in distress are not rescued with no-strings-attached support. They are nudged, then compelled, into reforms that align with global standards. The justification is always moral: good governance, climate justice, financial stability. But the outcome is always structural: diminished sovereignty, converged policy, and centralised control.

Greece’s 2010–2018 financial crisis is a textbook case: the country received successive bailout packages from the IMF and European institutions, conditional on harsh austerity measures and structural reforms. Pensions were slashed, public assets privatised, and domestic spending hollowed out. Policy autonomy was functionally ceded to the troika.

The Role of the UN: Providing the Ethical Mandate

The United Nations plays a pivotal role in legitimising this architecture by offering the ethical framework for transnational governance. But this role did not emerge spontaneously—it evolved directly from the League of Nations, the institution which first attempted to realise Leonard Woolf’s 1916 proposal for an 'international government'. Where the League failed to institutionalise authority after World War I, the UN succeeded by embedding its governance within financial, environmental, and humanitarian frameworks.

The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Agenda 2030, and international climate compacts provide the moral language that frames sovereign submission as responsible leadership. What appears as voluntary alignment is, in effect, structural convergence — especially when access to development funding, trade agreements, or investor confidence is contingent on SDG compliance, all in the name of the common good.

UNESCO Biosphere Reserves, for example, represent a powerful instantiation of this dynamic. By reclassifying land as part of the 'global commons', they elevate supranational environmental management above national law. In many cases, these reserves are funded or governed in coordination with World Bank programmes, linking ecological restrictions to the same transnational finance networks discussed earlier.

In Latin America, the Yasuní National Park in Ecuador became the subject of international negotiation when the government proposed to leave oil underground in exchange for global compensation. Though the initiative faltered, it set a precedent for internationalising sovereign land under environmental pretexts, with the UN functioning as the ethical broker of this exchange.

The UN, then, acts as the legitimising priesthood of the global financial order. Its doctrines — climate, equity, inclusion — mask the consolidation of control under institutions shielded from democratic oversight. It is the ethical shell over Woolf’s technocratic engine.

The Endgame: Managed Sovereignty

To understand the present system of supranational financial control, we must begin with three key historical thinkers whose ideas underpin much of this architecture:

Julius Wolf (1892), noted economist and chair of the revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg, proposed a financial model based on public-private coordination, anchored in gold, where monetary clearance could be administered not through sovereign transfer of assets but through centralised, expert-run mechanisms. This laid the groundwork for the BIS's ability to charge rent on public wealth held in trust by central banks.

Eduard Bernstein (1899), a leading revisionist Marxist, reimagined this system for a socialist-capitalist hybrid, promoting the idea that public institutions could be harmonised with private capital for the sake of the 'common good'. His vision of evolutionary socialism found renewed relevance in the World Bank’s blended finance structures, where risk is socialised and profit privatised, all justified through the language of collective benefit.

Leonard Woolf (1916), a member of the Fabian Society, provided the political-theoretical scaffolding in International Government, where he argued for a supranational administrative system that could enforce stability through technocratic coordination. This model, once utopian, is now realised in the form of the triad of the BIS, IMF, and World Bank—operating above states, directing policy, and enabled by the UN’s normative framing.

Together, these three figures offered a conceptual progression: from administrative control of money, to moral justification for centralised finance, to political institutionalisation of global governance. Their combined legacy is a global system that centralises authority, eliminates national autonomy, and replaces democratic accountability with stakeholder oversight.

Mark Carney, former Governor of the Bank of England and Bank of Canada, has been one of the most vocal advocates of this transition toward a coordinated, ethical-financial order. In his book Value(s): Building a Better World for All, Carney calls for re-aligning markets with moral outcomes by embedding stakeholder values into financial governance. He explicitly supports public-private partnerships, blended finance, and global coordination between monetary and fiscal authorities — a model he frames as necessary for climate transition and long-term resilience.

But beneath the aspirational rhetoric, Carney’s proposals echo the same technocratic consolidation that this essay outlines. His vision, while couched in progressive language, is a blueprint for the formalisation of a financial moral order — one that removes democratic uncertainty by binding decision-making to a global stakeholder consensus. His framework places central banks, multilateral development banks, and regulated financial actors at the helm of planetary management, backed by legal-institutional frameworks and guided by supposedly universal ethical norms. This is not reform. It is enclosure.

Case Studies of Financial Punishment

The triad's power is not limited to crisis response — it extends into active coercion. States that deviate from the dominant financial consensus risk being punished, isolated, or destabilised. When Iran was cut off from the SWIFT financial messaging system in 2012 under Western pressure, it marked the first time that a state's access to the global financial nervous system was revoked for political reasons. It set a precedent: access to liquidity and transaction networks is conditional.

More recently, Russia's exclusion from SWIFT and asset seizures by Western central banks following its invasion of Ukraine illustrate that global financial infrastructure is not neutral. It is a terrain of enforcement. What was once a shared utility is now a tool of economic warfare. Even before war, financial penalties are applied through capital flight, market withdrawals, and trade strangulation. Debt crises in Sri Lanka, Lebanon, and Zambia were all managed through externally imposed frameworks that prioritised creditor interests over popular sovereignty.

The Role of Sanctions and Ratings Agencies

Sanctions are only one form of pressure. Another, subtler weapon is the role of private credit ratings agencies — Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch — which act as de facto global referees of economic orthodoxy. A downgrade can cause capital to flee, raise interest rates, and make domestic borrowing impossible. Governments are often forced to adjust budgets or abandon social programmes simply to avoid a downgrade.

These agencies operate with no democratic mandate, yet their assessments determine whether a country is considered ‘investable’. They effectively enforce the policy preferences of institutional investors, reinforcing the same reform demands issued by the IMF and World Bank. This is governance by signal: economic compliance is rewarded, and deviation punished — not with bullets, but with spreadsheets.

Feedback Loops as Controlled Shock Therapy

The system’s most insidious feature is its ability to turn crises into opportunities for deeper control. When disaster strikes — whether via inflation, pandemic, or climate shock — the triad arrives with conditional relief. These are not simply bailouts; they are restructuring packages. The COVID-19 pandemic revealed this mechanism in real time: emergency central bank coordination stabilised markets, while the IMF issued support in exchange for reforms, and the World Bank used the recovery to expand SDG-linked financing.

This dynamic mirrors what Naomi Klein called the Shock Doctrine: the use of emergencies to override democratic resistance and impose structural reforms. But in the 21st century, the shocks need not be engineered — they are inevitable. And the infrastructure for response is already in place. Each crisis justifies more integration, more convergence, more conditionality. The result is a self-reinforcing cycle of dependency.

Colonial Continuity in Form, Not Name

This architecture does not merely resemble imperialism — it is its technocratic successor. Colonialism once extracted raw materials and labour by force; today, the same effect is achieved through debt, policy conditionality, and environmental covenants. The resource flows are financialised, the governance outsourced, the sovereignty hollowed out.

Kwame Nkrumah called this neo-colonialism: a system in which the forms of national independence remain, but the substance is gone. When a nation cannot set its budget without IMF approval, cannot spend on infrastructure without World Bank coordination, and cannot print money without BIS conformity, it is not free. The enforcement is softer. The outcome is the same.

Digital Infrastructure as the Next Layer

What was once a financial structure is fast becoming a digital one. Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) are being piloted as programmable money — tools that could restrict spending by sector, expiration date, or user identity. Climate risk is being embedded into capital allocation models, with AI scoring systems set to determine everything from creditworthiness to access to development funds.

These systems introduce a new phase: one where algorithmic governance, ESG compliance, and real-time surveillance form the substrate of global economic life. The future triad will not just enforce policy. It will predict, score, and condition it — automating obedience in the name of ethics and sustainability.

What emerges from this system is not a conspiracy, but a structure—a supranational framework of governance that grows stronger with each crisis. Whether the shock comes from inflation, pandemic, environmental collapse, or sovereign default, the response is always framed as rational, necessary, and moral. But each time, it results in a deeper transfer of authority from the nation-state to the triad of BIS–IMF–World Bank, under the narrative stewardship of the UN.

This is exactly the pattern Leonard Woolf imagined in 1916: a system of international governance so embedded, so rationalised, and so automatic that it would make national sovereignty obsolete not by overthrow, but by attrition. The mechanism of control is not force, but dependency. Each institution reinforces the others:

BIS enforces monetary discipline that limits national flexibility.

IMF steps in when crises emerge, dictating reform through conditionality.

World Bank drives long-term structural alignment, embedding policies through funding mechanisms.

The cumulative effect is a depoliticised global order where critical decisions — about money, taxation, investment, and land — are increasingly made by institutions no voter can unseat. What was once theory has become operational: an international government by function, not form.

In the final analysis, this system does not formally abolish the nation-state. It empties it. Monetary autonomy is bounded by BIS standards. Fiscal discretion is constrained by IMF ceilings. Infrastructure and land are governed through World Bank frameworks. All of it is presented as technical, neutral, and benevolent.

But the result is a world in which the most important levers of policy — money creation, public spending, land use, and development — are administered by institutions that exist above the level of democratic control. Over time, this structure facilitates a progressive monopolisation of global assets. As land, water, carbon, and biodiversity are financialised and collateralised under transnational frameworks, ownership becomes increasingly concentrated in the hands of institutions, consortia, and stakeholder networks.

Individual ownership, while not formally outlawed, is functionally eliminated through a combination of debt mechanisms, conservation restrictions, regulatory compliance requirements, and capital access barriers. The rhetoric of inclusion and justice conceals a reality of consolidation. The public, promised protection and sustainability, finds itself locked out of ownership and decision-making in the very systems built in its name.

It is Woolf’s vision realised: an international government — not elected, and accountable to no one. Once in place, it cannot be voted out. Because it was never voted in.

Conclusion: From Technics to Totality

What began as Julius Wolf’s proposal for an efficient, expert-administered system of monetary clearance was recast by Eduard Bernstein as a moral project — one where private capital and public governance could be harmonised under the ideal of collective welfare. Leonard Woolf, in turn, transformed this synthesis into a political blueprint: a supranational apparatus to ensure peace through interdependence, order through administration, and reform through technocratic consensus.

Each thinker believed they were building something stable, rational, and humane. But their cumulative vision — monetary neutrality, social harmony, administrative authority — was not immune to capture. In fact, it enabled it.

For once the scaffolding was erected — clearing systems, conditionality mechanisms, stakeholder governance models — it required only alignment, not conquest, to fall under the influence of a single coordinating power. That power need not be visible, or even singular in name. It operates as a consensus of institutions, a network of enforcers, a system that moves as one.

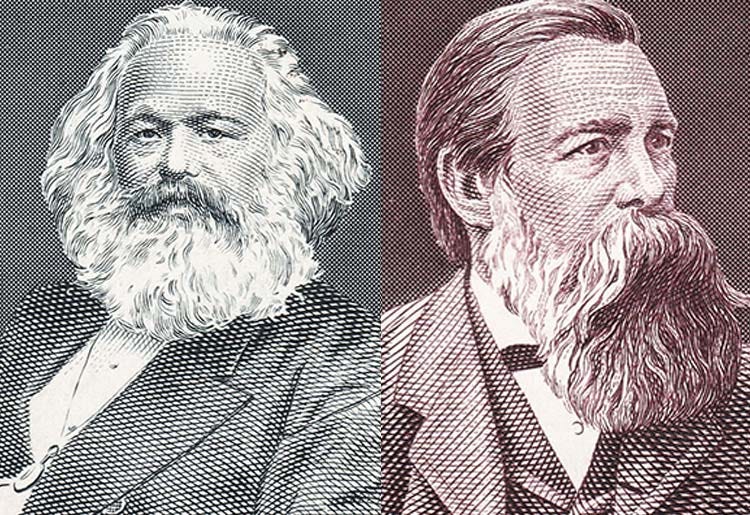

In The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels warned that ‘the executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie’. They also foresaw that capital, in its constant drive to overcome limits, would globalise, centralise, and eventually subsume all competing sovereignties into a unified logic of control.

What they described as the inevitable concentration of economic and political power — beyond nations, beyond markets, beyond parliaments — is not only underway. It is already operational.

A financial system designed for efficiency became a moral system for global administration. A moral system became a political infrastructure. And that infrastructure now governs in the name of sustainability, equity, and peace—while consolidating the very power Marx and Engels predicted: not dispersed among nations, but centralised above them.

Not by revolution — but design.

Absolutely magnificent article Dr. Nass. Thank you so much and, for the umpteenth time, thank you for all the work you do in support of human health and human freedom. You are an exemplary human being.

Communist theory has never been successfully implemented in practice because of inherent and inevitable human greed. We are experiencing Technocracy and Algocracy (rule by Artificial Intelligence algorithms) for the benefit, profit and control of the Bank of International Settlements, governments, multinational corporations and the military-industrial-intelligence-pharma complex aka public-private partnerships. This is de facto DISASTER CAPITALISM USING MKULTRA SHOCK THERAPY FOR ASSET-STRIPPING OF WORKERS.

https://canadianshareablenews.substack.com/p/far-left-far-right-totalitarianism?utm_medium=email&utm_content=post