Development for Finance

There is no shortage of grand claims in the world of sustainable development finance. Trillions, we are told, must be mobilised. But fortunately, private capital and philanthropes stands ready to partner with the public sector in a drive to save the world by helping to altruistically deliver the Sustainable Development Goals, transition energy systems (to unproven alternatives), and build resilience against the shocks of all the climate change which won’t take place.

And the mechanism to save us all? Blended finance.

We have dealt with the topic of Blended Finance before, but in essence — blended finance refers to the use of public, philanthropic, or concessional capital (grants and loans, priced considerably cheaper than the market does) to 'de-risk' investments and attract private finance into new ventures for the alleged sake of planetary stewardship. It is sold as a pragmatic solution to the funding gap — a way to align the goals of investors and society. But dig beneath the surface, and the reality is somewhat at odds with what you’re commonly told.

The reality is that blended finance is — in no uncertain terms — a wholesale public subsidy of the private investor, where the philanthrope likely only contributes to set early direction, and to collect credit which isn’t theirs to take.

And to understand why and where this all leads, that’s the objective of this post.

The Mobilisation Mirage

The language is consistent across reports from the OECD1, World Bank2, GEF3, Rockefeller Foundation4 and others5: blended finance is a success story in the making. Leverage ratios of 1:5, 1:10, even 1:35 are routinely cited, suggesting that for every dollar of public money, ten or more dollars of private capital are attracted. But these figures are frankly nothing short of — at best — ENRON quality accounting.

Even the more conservative estimates rely on ‘gross mobilisation figures’, not ‘net private contributions’. A typical project might claim to have ‘mobilised’ $100 million in private finance — but a closer inspection is not uncommon to reveal that the majority was not only public funds reclassified as private, and what is legitimately private was only invested given artificially, taxpayer-backed deals which not only guarantees extraordinary returns, and a practical wholesale insultation from legit risk. Heads, the private investor wins, tail, the public loses. Lemon socialism. 2008 on repeat play.

Recent figures quote $21.9bn private mobilisation investment out of $115.9bn6 which would suggest 19% invested by the private investor - already a significant reduction compared to most marketing material you’re likely to see. However, the $21.9bn figure includes capital sourced from public organisations under government control, yet wholly independent, funded through taxpayers. When you strip away all indirect subsidies7, a common percentage arrived at is 35-45%8 of the figure being actual private capital in the least developed country proposals9 — which lands at 7.7% and thus almost exactly the 8% figure I estimated in the first post on the topic.

Even the IDB Invest10, DEval11, and the Global Environment Facility admit that actual private mobilisation is far lower than quoted figures, often around 10% of total capital flows, and sometimes lower still. The bulk of climate finance and development investment is coming from taxpayer-backed sources12, while the private sector often takes a wait-and-see approach, entering only after risks have been neutralised and markets pre-structured. And when they finally enter, they cherry pick the most lucrative, risk-free tranches — and even promote their activities through the lens of ‘serving the common good’, when reality is they capitalise on public funds.

For example, in the South Africa JETP13, nearly all of the capital mobilised to date is from public or concessional sources. Private investors have shown some interest — but primarily in grid upgrades and commercially viable renewables, not in socially necessary, lower-margin transitions such as coal community reskilling or public transport decarbonisation.

Yet, many projects are structured to inflate the appearance of private participation. Public development banks or MDBs may lend on semi-commercial terms and are then counted as ‘private actors’ for accounting purposes. In other cases, domestic capital from state-owned banks or pension funds is bundled into the ‘private’ category — obscuring the true source of capital.

In effect, blended finance becomes a subsidy machine: public money accepts the losses, while private actors reap the rewards. The high leverage ratios touted in glossy investor briefs are not proof of success — they exist to make it appear as though market actors are leading the charge, when in truth they are being paid to show up14.

Where Does the Money Come From?

The answer is simple but rarely stated with honesty: the vast majority of blended finance flows originate with the public. Whether channelled through multilateral development banks (MDBs), donor governments, or national development agencies, the capital at the base of these financial structures is backed by taxpayers15.

The first layer typically consists of concessional capital — grants, soft loans, and guarantees — virtually entirely provided by public institutions, though philanthropic foundations like to claim they partake as well (though in reality, their contributions are so small they might as well partake at all, but probably do because their funds tend to be early and earmarked for special purposes). These serve as the 'first-loss' tranche in investment structures, shouldinging risk to entice private co-investment. This capital is often derived from aid budgets, climate funds, or pandemic-related emergency packages that have since been reclassified under the banner of 'climate-health finance'16.

Next come the development banks — entities like the World Bank, EBRD, ADB, or GCF — whose balance sheets are built on government contributions. These institutions offer low-interest loans, equity, or guarantees, typically below market rates. Not only do they fund projects, but they also give private investors the comfort that projects have been de-risked and structured appropriately.

Then there are the national finance ministries and sovereign wealth funds which — often under international pressure — are told to 'crowd in' private finance by creating co-investment vehicles, guarantee facilities, or policy incentives. Whether the funds come from taxpayers, debt issuance, or redirected budget allocations — the source is ultimately public.

In several recent JETP17 and GEAPP18-aligned projects, the pattern is the same: philanthropies donate little but early to set the initial direction, development finance institutions cover early-stage costs and risk, MDBs scale the investment and provide structure, and only then do private financiers enter — with returns often guaranteed or collateralised, meaning in the event of bankruptcy, they can have a lien in the underlying asset such as land ownership or rights of exploitation. In reality, however, this is extremely hard to prove as all project and finance documentation is not available to the public, regardless of the public being the much larger investor.

What is sold as an equal partnership is, in fact, deeply asymmetrical19. The public sector takes on the systemic risk of the transition; the private sector collects the return. And the language used — 'mobilisation', 'de-risking', 'catalytic capital' — functions not as description, but as marketing. These are glossy terms, enabling the private investor the opportunity to hide among yet more indirect taxpayer subsidy, making it appear the private partners shoulders their ‘fair’ levels of risk.

The SDG Asset Class

Blended finance was initially framed as a way to support development goals that could not be funded through commercial investment alone. But in practice, it has enabled a quiet transformation of the Sustainable Development Goals into a range of investment themes. Each SDG — those parts which are commercially viable — is now treated as a potential revenue stream.

Rather than pursue broad development aims through democratically governed public budgets, the logic now runs in reverse: SDG targets are deconstructed into discrete, monetisable components that can be fitted into financial products, similar to those which catastrophically failed in 2008. Microfinance for women becomes SDG 5.220. Solar mini-grids in villages become SDG 7.121. Pay-as-you-go sanitation platforms become SDG 6.222. These projects are then gathered, securitised, tranched, and scored through ESG metrics to attract private capital.

In this way, the SDGs are not just a moral compass — they are increasingly a catalogue for structuring blended finance deals. What qualifies for investment is what can be measured, commodified, and de-risked through public largesse23. Yet, even within ostensibly green or equitable projects, only the aspects with predictable cash flows (and positive PR) tend to receive funding.

The documents are voluminous. Reports from the Rockefeller Foundation, Systemiq24, UBS25, and the World Bank all describe how impact investing, carbon finance, and climate-resilient infrastructure are being mapped directly onto the SDGs, and how said organisations are doing us all a favour in that regard. The United Nations in collaboration with the World Economic Forum, have even published guidance on how private finance can align portfolios with the SDG framework.

But this is not alignment in a moral sense — it is alignment in a investor portfolio-construction sense. Blended finance does not reform the logic of capital; it retools development to serve that logic. The SDGs — once framed as a universal call to solidarity — are now the blueprint for asset classes, with a few being cherry picked by private investors as these constitute a virtually guaranteed public subsidy, while shouldering little to no risk.

This is not by accident, but the express intent. And it sets the stage for what comes next: the normalisation of a world in which finance governs development priorities through the language of planetary stewardship26 and virtue by indicator27.

Toward a Programmable Financial Order

The retooling of development finance through blended structures is not merely a trend in how capital is deployed. It is the precondition for something more ambitious: the transformation of the financial system itself. The future is not one where finance serves development. It is one where development becomes a function of programmable finance, enabled by CBDCs and Circular Economy surveillance.

At the heart of this emerging regime is a logic of alignment. Investments must align with system-level goals: decarbonisation, resilience, equity, sustainability. But crucially, alignment is not judged by voters, nor by parliaments — it is deliberated through metrics-yielding Digital Twins, operating through forward prediction of the continuous global surveillance data that it receives. See, financial flows are increasingly governed by performance indicators, ESG scores, carbon intensity, and resilience indices meaning that capital is no longer neutral, but moralised — and therefore subtly programmable.

This opens the door to more radical transformations28. Central banks and multilateral institutions are now actively exploring tools like carbon-backed central bank digital currencies (CBDCs)29, impact-linked monetary instruments, and ‘positive money’ frameworks where credit issuance is directly tied to sustainability outcomes, with all credit fully controlled by the central bank. These are not fringe proposals — they are being tested in regulatory sandboxes and pilot programs by the BIS, IMF, and aligned consortia, such as the Network for Greening the Financial System.

Blended finance, in this context, is the prototype. It tests the political, legal, and technical structures necessary to ensure capital flows can be directed not only by market demand but by ethical objectives — the common good, for lack of better term. Public-private partnerships become algorithmic policy instruments, where incentives are continuously adjusted in programmable contracts. Funding becomes contingent on adherence to externally defined sustainability logics, and this logic is almost certain to change, in effect rewarding those who can keep up with the changes.

On paper, it looks like progress, and it’s sold under the guise of planetary stewardship. But in practice, it shifts power away from democratic institutions and toward a technocratic elite, which also get to administer the ethical code — entirely outside democratic capacity.

And as more national governments are nudged into creating 'investment-ready environments' — country platforms, resilience dashboards, policy banks — what emerges is a standardised interface for planetary investment governance, and this of course calls for harmonisation of rules across the investment landscape. The purpose of money itself is being redefined — not to circulate freely within an open economy, but to steer behaviour toward externally validated futures, which will down the road translate into continuous, full-spectrum micro-nudges towards ‘responsibile consumption’.

In short — blended finance was likely never just a funding mechanism. It was the training ground for a new monetary regime. It was the mixing of private capital and public… capital, working for… the common good.

Eduard Bernstein squared, in short.

'In Tandem' Convergence

The Fabian Society’s In Tandem report made a rare admission: that the scale and urgency of alleged 21st-century crises — climate instability, energy transitions, regional inequality — require coordinated action between central banks and treasuries. In other words, fiscal and monetary policy can no longer operate in silos, but must rather work ‘in tandem’ to steer the economy toward long-term public missions. And given what took place when Truss and Kwarteng dared operate outside of pre-approved policy, it should be absolutely bloody obvious to anyone paying attention this results in the transferring of fiscal policy control, very gradually, to the central banks.

Global institutions of course rarely speak in such direct terms. Instead, we hear about catalytic capital, just transition pathways, and investment-ready pipelines all serving the common good. But beneath the veneer of rhetoric, the underlying structure mirrors In Tandem almost exactly, because blended finance doesn’t work without macroeconomic coordination. Private investors will not enter high-risk, low-return markets without guarantees. Investment pipelines cannot scale without concessional capital. And ESG metrics are useless without regulatory harmonisation, because investing in biodiversity ventures in Bolivia demands a similar framework to that in used in Moldova. And for all this to function, public and financial authorities must act in concert — and that typically takes systemically aligned mandates.

This is where the In Tandem30 logic becomes global. Multilateral development banks play the fiscal role through concessional loans and project structuring. ESG taxonomies and climate disclosure standards impose the language of common good morality. And central banks — while rarely named — supply the backstop: through green bond eligibility, risk-weighted capital guidelines, and selective credit interventions.

But perhaps the most important institutional player is the Financial Stability Board31. The FSB sits at the intersection of central banks, financial regulators, and systemic risk managers. It does not deal with capital, but rather it seeks to create the rules which capital must obey. And if something is defined as a threat to financial stability — climate change, biodiversity loss, even pandemics — it enters the monetary mandate. Central banks are then justified in taking a ‘non-neutral’ positions in favour of systemic mitigation — for ‘our common good’, you see.

This then leads to cover for monetary involvement — entirely without public debate. It next allows institutions like the IMF and World Bank to support reforms that harmonise public and private finance under a single, global architecture. Country platforms, SDG-linked bond frameworks, and investment alignment tools like the Zero Gap Fund32 are all extensions of this convergence.

In this model, In Tandem was an early announement, detailing how future sovereign monetary authority33, public investment strategy, and private capital mobilisation is planned to operate as a single apparatus.

What we see globally — from the JETP country platforms to the Rockefeller-aligned MDB reform plans — is the scaling up of the same model, with the degree of discretion, the role of unelected stakeholders, and the same complete absence of democratic oversight applied globally. The result will become a technocratic investment regime, with central banks underwriting a planetary economic transition legitimised by ‘common good’ morality, shielded from political accountability.

The Reality of Control

Blended finance is marketed as a win-win arrangement — public and private sectors working hand in hand to solve the great, alleged challenges of our time. But the evidence tells rather the different story. Private capital is not being mobilised at scale, yet reaps the rewards, while public finance — from taxpayers, donors, and multilateral banks — underwrites nearly all the risk, and receive a very, very poor return.

This is not a partnership, but a financial architecture built to reorient development toward the interests of the investor under a veneer of morality. The SDGs — once framed as a universal moral agenda — have been sliced into investable propositions, and outcomes are measured in emissions indicators, ESG compliance, and virtually entirely risk-free returns for the private investor.

What began as an alleged, accompanying mechanism to close the funding gap has matured into a governance system — a programmable model for directing capital toward specific futures, which can even be subtly shaped or front-run by those altruistic philanthropes and private investors. And as the In Tandem model is scaled globally, the lines between monetary policy, fiscal policy, and public investment disappear — not through democratic decision, but through technocratic, structural convergence.

The central actor in this convergence is not the sovereign state. It’s not even the market. No, it’s the central banks, the MDBs and the CSOs directing the common good, harmonised gradually through the Financial Stability Board34 — all operating entirely outside of democratic mandate.

Blended finance is not merely a flawed tool — it is a Trojan horse. Regardless of promises, the result is monetisation of climate, resilience, human needs, and to further restructure the future — to normalise a regime in which public wealth subsidises private profit, ‘common good’ moral imperatives are translated into metrics, and the role of democratic oversight is quietly eliminated by central banks, development institutions, and unelected technocrats, defining our ‘common good’… though especially central banks.

This is not finance for development. It is development for finance.

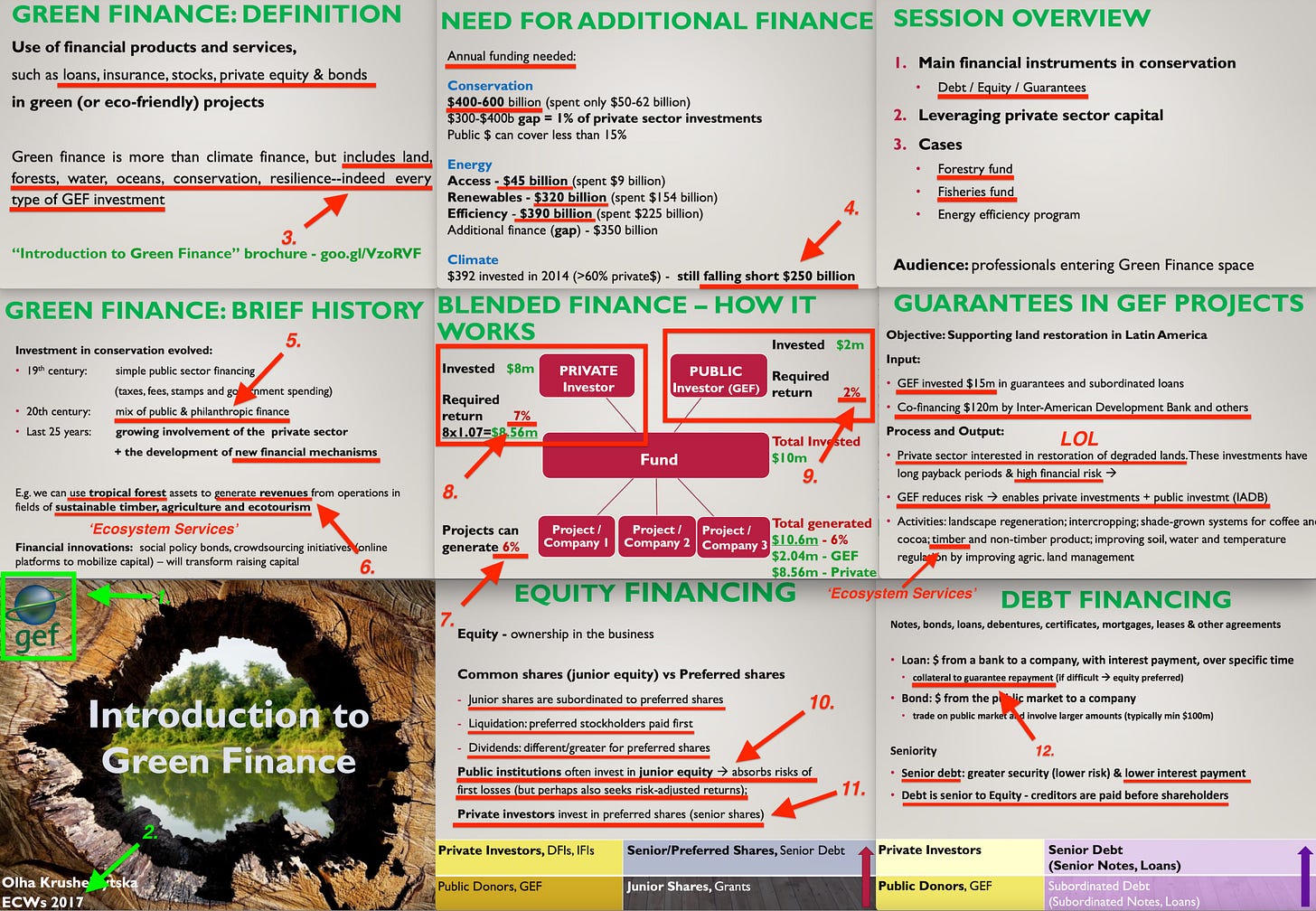

Let’s finish off with a document from the GEF’s own site35. I added numbered arrows, hopefully easing comprehension as this is a complex topic — by design.

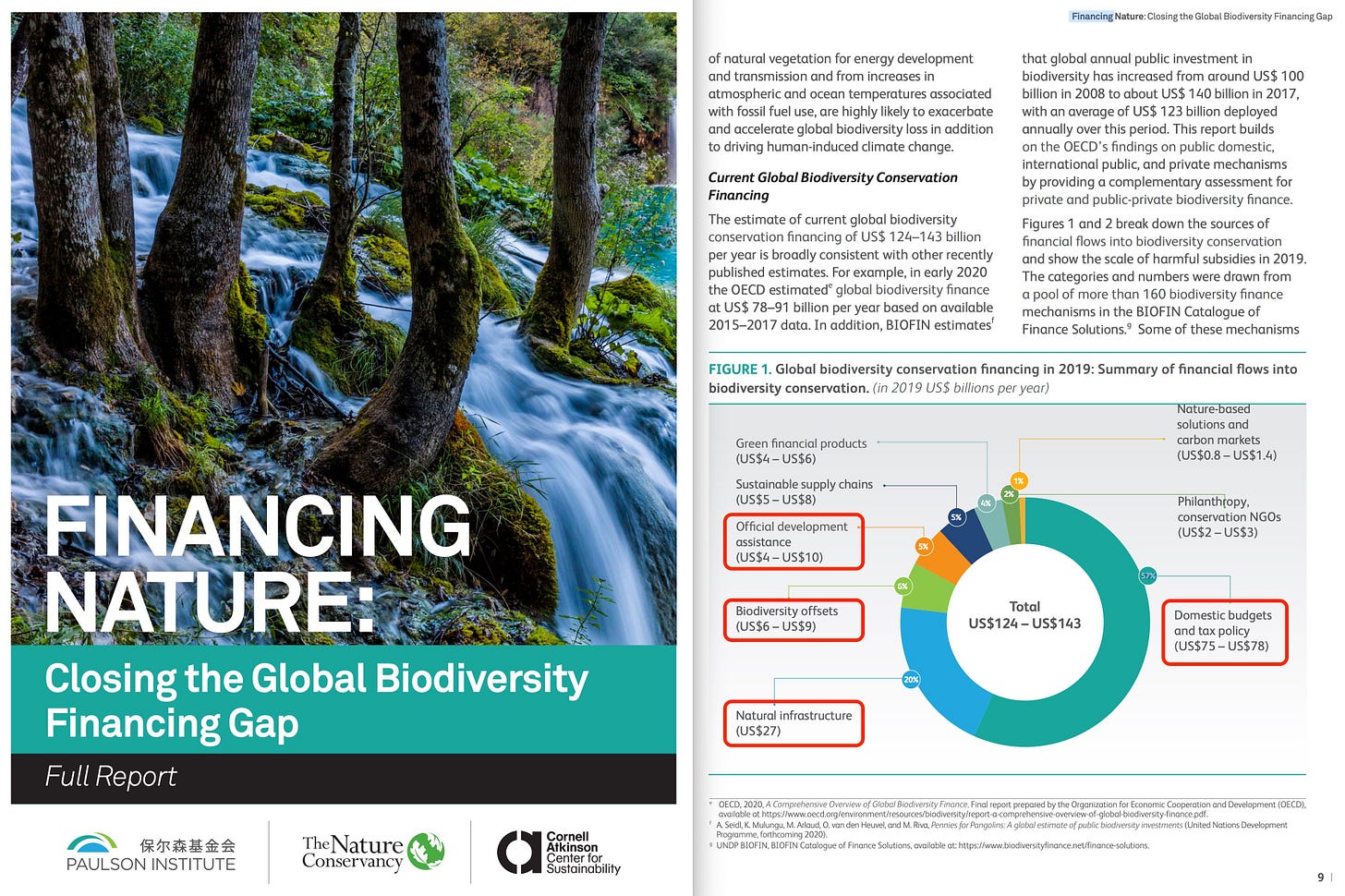

First off (1) - the document comes courtesy of the GEF, and it was (2) released in 2017. And (3) makes clear that this is the GEF's turf; land, forests, water, oceans... ie, reserves, typically in the UNESCO Biosphere Reserves (or heritage sites).

We learn that regardless of the billions and utter billions of taxpayer 'investments', (4) it quite simply is not enough. In 2017, we were $250bn short! Financing is done via debt (bonds), equity (shares), and guarantees (guaranteed interest payments; collateral). All of this (5) is - allegedly - a mix of philanthropic, private, and public capital. And we see (6) that the objective here is to make money from 'ecosystem services' (which - although unlisted - also include carbon credits).

The next slide is the first of primary importance, because it (7) outlines that a given project can only generate 6% yield, but (8) private equity demands 7%, meaning (9) the public (taxpayer) will simply have accept a 2% return, which in short translates to a colossal transfer of taxpayer funding to the private investor.

And the key to understanding how said 'structure' allows this brilliant investment (from the perspective of private equity, anyway), is to grasp that equity dividends are higher than bond interests, and consequently, private equity receives equity, and the public receive bonds.

However, we still have the issue of risk, because private equity doesn't like losing money. To avoid that, (10) the public will be 'junior' ('mezzanine') in the relationship, while (11) private equity will be senior. That ensures that the taxpayer will lose every penny of their investment, before private equity loses even a single one.

However, (12) should said investment collapse, private equity will likely still demand security, and this could happen through either a transfer of the underlying collateral to said private equity. Other sources suggest private equity might also demand a guarantee of steady interest payments regardless, which could mean the public taxpayer would have to stomp up interest payments, should the business collapse. In fact, this appear exactly what’s taking place in Iwokrama, the complete failure of a pilot scheme, which is kept running regardless.

The bottom line here is that blended finance is nothing short of a colossal scam, structured much in line with those ultimately collapsed CDOs back in 2008.

But this time with the taxpayer - ie, that would be you - the sitting duck.