What on earth can the population of a 450‑square‑kilometre archipelago of coral atolls off the east coast of New Guinea teach the world about economics, as per a chapter from 1921 in an obscure book?

Well—however absurd it may appear—quite a lot, some would suggest.

The book in question is titled Cultures of the Pacific1, and it was published in 1970. We specifically focus on chapter 6 in this regard2. An issue of the Royal Economic Journal from 1921 confirms its release3.

In full disclosure—I expected this to recommend middle-age guild-like systems; cooperatives, including public and private partnerships, collectively working for the common good, as laid out by Eduard Bernstein in 1899. The model which we have seen employed again and again and again and again…

And yes—that genuinely is the same model, employed again and again and again. Though Tony Blair framed it as The Third Way, the same concept materialises as Wolfgang Reinicke’s Trisectoral Networks in UN capacity, Lenin’s New Economic Policy, or even Deng Xiaoping’s reforms and the IFDA’s Third System (which relates to the New International Economic Order rolled out in the 1970s)—you can, in fact, easily track it back to the League of Nations and Leonard S Woolf’s International Government. I really am not kidding—it genuinely is the same model.

While—by logical deduction—the above is present, this article delivers so, so, so much more, and in fields I hadn't even considered. In fact, although some of these topics were touched upon in 1936 through Technocracy, Inc, I somewhat expected that to be the origin. But let’s begin:

In this article I shall try to present some data referring to the economic life of the Trobriand Islanders, a community living on a coral archipelago off the northeast coast of New Guinea…

I have admittedly never heard of them previously, but in the event you’re as ignorant as I4, here5 they6 are7—a tiny group of islands close to Papau New Guinea.

A cynic might wonder for how long they searched to locate a such expedient example?

Ah, but inner voice, you’re such a cynic:

The questions before us are, first, the important problem of land tenure; next, the less obvious problems of the organisation of production

Then again… perhaps not. Land tenure has been one of the major research efforts in our glorious dictator’s multi-generational projects, because outright stealing land at the barrel of a gun tends to be a highly visible solution. As for the organisation of production—that sounds right up Bogdanov’s alley, as his Tektology explicitly relates to a social and natural science synthesis, where social science relates to organisation.

Land tenure among the Trobriand natives is rather complex… as many as five different “owners” to one plot—each answer, as I found out later on, containing part of the truth, but none being correct by itself.

Suddenly, a light flashes in my brain: the Ecosystem Approach, which in short describes integrated, top‑down landscape management. And five different owners—it could further relate to the different types of ecosystem services… though we'll focus on the former… for now…

And the extraordinary coincidences are in no short supply here:

The chief (Guya’u) has in the Trobriands a definite over-right over all the garden land within the district… The garden magician (Towosi) also calls himself the “master of the garden” and is considered as such, in virtue of his complex magical and other functions, fulfilled in the course of gardening… each garden plot belongs to some individual or other in the village community, and, when the gardens are made on this particular land, this owner either uses his plot himself or leases it to someone else under a rather complicated system of payment

We have a structural outline of a hierarchical ownership system, evident in the Ecosystem Approach, yet fundamentally relying on the general principle of subsidiarity—where things are said to be 'decentralised to the lowest appropriate extent'—even though no one bothers to explain what that entails on a global scale. Oh, and we also have those leases… oh wait…

We skip over the details relating to the growing season, but in short, the garden magician is the organiser of the collective small-scale plots:

Thus, we can answer the questions, referring to the organisation of production, by summing up our results, and saying that the authority of the chief, the belief in magic, and the prestige of the magician are the social and psychological forces which regulate and organise production; that this latter, far from being just the sum of uncorrelated individual efforts, is a complex and organically united tribal enterprise.

But as for similarities with the Ecosystem Approach:

They have a keen interest in their gardens, work with spirit, and can do sustained and efficient work, both when they do it individually and communally. There are different systems of communal work on various scales; sometimes the several village communities join together, sometimes the whole community, sometimes a few households

See, a central aspect of the Convention on Biological Diversity's finest relates to a strict top‑down hierarchical organisation of land. And that—by sheer coincidence—is what these islanders, in the middle of nowhere, landed on as well—a hundred years ago. In fairness, it's a fairly common system; it's just that we in what's commonly considered the more civilised world eliminated it hundreds of years ago because our regional experiments with feudalism led to oppression, large‑scale violence, and obscene levels of exploitation.

And just to establish that this relates in general—not only to gardening:

We have discussed their production on the example of gardening. The same conclusions, however, could have been drawn from a discussion of fishing, building of houses or canoes, or from a description of their big trading expeditions. All these activities are dependent upon the social power of the chief and the influence of the respective magicians. In all of them the quantity of the produce, the nature of the work and the manner in which it is carried out—all of which are essentially economic features-—are highly modified by the social organisation of the tribe and by their magical belief

Their entire political economy, essentially, is structured around feudalism. Wait, no, that’s too kind a term:

… the obligations, imposed by rules of kinship and relationship-in-law, and the dues and tributes paid to the chief. The first-named obligations involve a very complex redistribution of garden produce, resulting in a state of things in which everybody is working for somebody else. The main rule is that a man is obliged to distribute almost all his garden produce among his sisters; in fact, to maintain his sisters and their families

No, it appears closer to some odd merger between quasi-communism and feudalism:

… it enmeshes the whole community into a network of reciprocal obligations and dues, one constant flow of gift and counter-gift

What this sounds like is this:

You have the responsibility to uphold the collective rights of others.

You bump into that principle rather a lot when you read up on the Soviet Union. See, in collectivist societies, you only have the rights which others grant you. And that’s extremely useful, if you’re one of the few who seek to grant no-one else rights.

Ain’t that so, Emmanuel Levinas8?

This constant economic undertow to all public and private activities—this materialistic streak which runs through all their doings—gives a special and unexpected colour to the existence of the natives, and shows the immense importance to them of the economic aspect of everything.

Wait, no, now it sounds like a system centered around distributive and contributive justice, equity, social justice, dignity, and the common good.

But we immediately snap back to the middle ages:

To return to this, we must first consider, what part of the whole tribal income is apportioned to the chief. By various channels, by dues and tributes, and especially through the effect of polygamy, with its resulting obligations of his relatives-in-law, about 30 per cent of the whole food production

To the best of my knowledge, a tenth of income was taken by the landowners, a tenth by the Church, and a tenth by the State during feudal Europe. What he appears to propose here is a return to that system. But what I don't recall from history lessons in school is this:

The chief is, as a matter of fact, also the only person who can accumulate, and, as a matter of privilege, the only one who is allowed to own and display large quantities.

The commoner is not allowed to accumulate. The commoner, clearly, has to live day-to-day, and this is further emphasised through:

Another important privilege of the chief, is his power to transform food into objects of permanent wealth. Here again, he is the only man rich enough to do it, but he also jealously guards his right, and would punish anyone who might attempt to emulate him, even on a small scale.

Not only is the chief the only person allowed to retain a store of value, but he will actively punish those who try to secure the future of their children. And, as mentioned, should the commoner seek to evade his wishes:

The essential of power is, of course, the possibility of enforcing orders and commanding obedience by means of punishment. The chief has special henchmen to carry out his verdicts directly by inflicting capital punishment, and they must be paid by Vaygua

The chief even has his own private mercenaries enforcing his top‑down rule. I mean, delightful—who wouldn’t want to return to this system?

Oh wait, on that note:

Even more important than the exercise of personal power is the command, already mentioned once or twice, which wealth gives the chief over the organisation of tribal enterprises. The chief has the power of initiative, the customary right to organise all big tribal affairs and conduct them in the character of master of ceremonies

Not only does the chief have his own private mercenaries, but he also dictates which enterprises should even be allowed.

That, for the record, is a model shared by the European Union, where the power of legislative initiation is placed with the horrible, undemocratic commission. If there is one single reason why the EU should be immediately disbanded, it is this: the commission—SELECTED, not elected—repeatedly refuses to listen to legitimate concerns. They simply won't listen to 'nationalists' and, as Clinton would say, 'baskets of deplorables', regardless of whether they were democratically elected.

The way the chief is continuously reported is telling:

In these, as we saw, the chief, by means of gifts, imposes a binding obligation on the participants to carry out the undertaking, and by means of periodical distributions he keeps everyone going during the time of dancing, merry-making, or communal working

So as long as the chief showers the contractors with money, it becomes an obligation for them to stay? I'm pretty sure employment tribunals would have a field day with that here in the more civilised world, but:

We see, therefore, that in following up the various channels through which produce flows, and in studying the transformations it undergoes, we find a new and extremely interesting field for ethnological and economic interest. The chief’s economic role in public life can be pointedly described as that of “tribal banker,”

… so… a top-down dictatorship, through force and bribery and threats of economic fines, where the dictator is considered a ‘banker’ is a ‘new and extremely interesting field’? For whom, exactly? Central bankers?

Thus I speak of “the chief,” whereas in a more detailed account I would have shown that there are several chieftainships in the tribe with a varying range and amount of power. In each case the economic, as well as the other social conditions, are slightly different

And this inclusion is noteworthy—recall how we discussed overlapping ecosystem services? Well, as it transpires, they have overlapping chieftainships, depending on which matter is being addressed.

Now, I don’t know if this is a particularly good example, but imagine if one chief were in charge of fishing, another of farming, and a third of wooden plates. That would, in short, give birth to several monopolies, each overlapping in geographical region. It would be a perfect match for the new, top-down centrally planned 'economy', centred around alleged biodiversity and carbon emissions.

Through the institution of chieftainship and the belief in magic, their production is integrated into a systematic effort of the whole community.

Well, yes, under various forms of penalties and punishment should they refuse—ultimately monopolising reward with the chief.

We have not spoken of exchange yet…

We certainly have not:

It is at first sight evident that ‘money’ in our sense cannot exist among the Trobrianders. The word currency—differentiated from money in that it is an object of use as well as a means of exchange

… but as for as a store of value:

Money also, as a rule, serves as the standard of deferred payments. It is obvious at once that in economic conditions such as obtain among the Trobrianders, there can be no question of a standard of deferred payments, as payments are never deferred

No, stores of value are not for the proles. The commoner cannot save money, and all payments must be made immediately, meaning there can be no debt either. Next, we have a description of a system where every trade is made according to predetermined exchange ratios through mutual coincidences of wants, where one tribesman swaps a number of agricultural products for another. In other words—a system of fixed exchange ratios, which to me sounds like complete and utter nonsense, because just as we cannot predict future climate, those islanders for sure can’t predict next year's coconut yield in advance.

All the trade is carried on in exactly the same way—given the article, and the communities between which it is traded, anyone would know its equivalent, rigidly prescribed by custom. In fact, the narrow range of exchangeable articles and the inertia of custom leave no room for any free exchange, in which there would be a need for comparing a number of articles by means of a common measure.

Not only is there this rigid system of exchange, but there's also no flexibility for introducing new items at the local level. Any external trade must go through the chief (or he'll set his mercenaries upon you).

Still less is there a need for a medium of exchange, since, whenever something changes hands, it does so always because the barterers directly require the other article.

Their trade system is quite simply horribly inefficient—if you have 10 coconuts and want to trade for yams, that trade depends on finding someone who wishes to swap in reverse. For this exact reason, a currency is usually introduced. But as we saw above, money is exclusively the privilege of the chief. Consequently, what is required is two currencies: one for transactions and one that serves as a store of value. And, by extraordinary coincidence, that is precisely what positive money seeks to implement at this very moment.

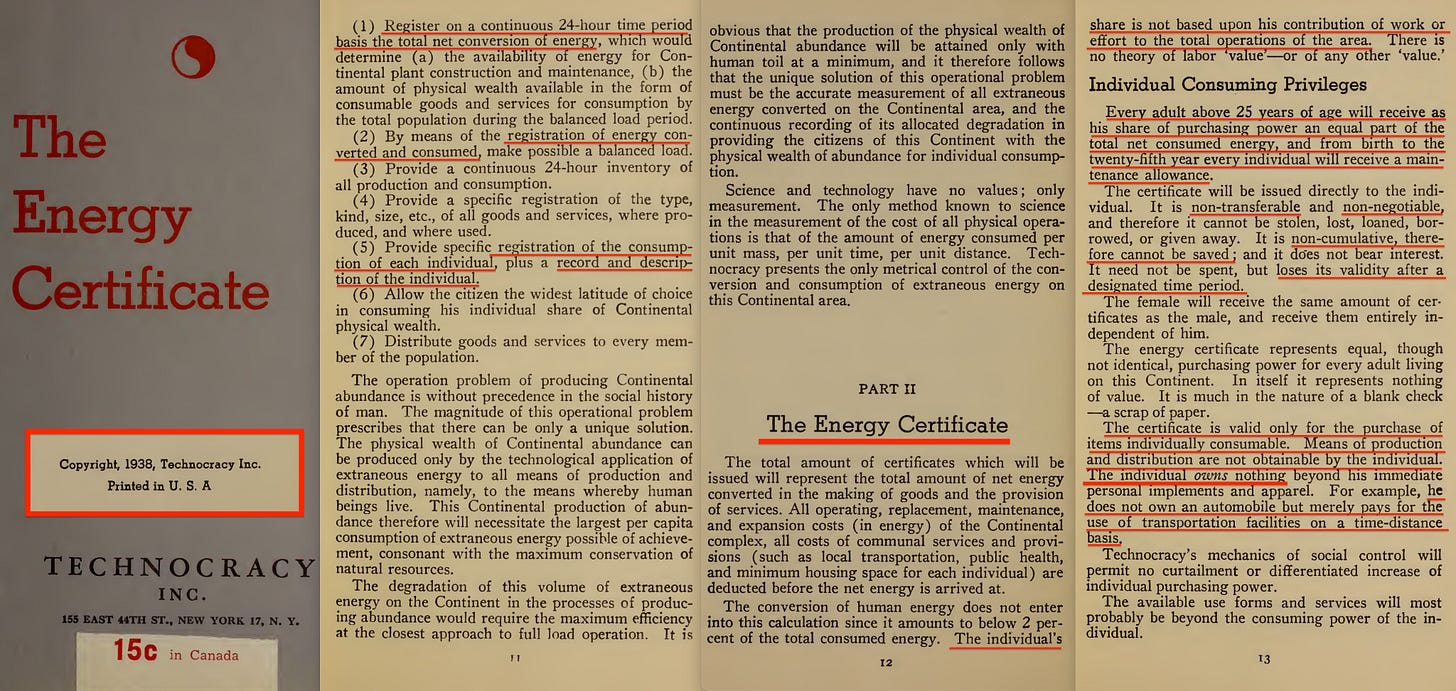

Of course, before proposing this solution, Technocracy Inc suggested much the same through energy certificates9 which cannot be used as a store of value either.

In fact, according to their vision, the individual will own nothing.

Unsure if they’ll be happy, because the document doesn’t say.

But in more contemporary terms, we now have not one but two carbon‑backed CBDCs—one backed by carbon emissions (comparable to a trading currency with an expiry date) and the other by sequestration, which can be likened to a store of value.

… and isn’t it just incredible how well-aligned with the 1992 Earth Summit that is?

So to summarise—a little-known tribe a hundred years ago had arrived at a political economy which, in essence, used two currencies—though they hadn’t yet invented the one for trading. This system employed the principles of subsidiarity, a land tenure system similar to the Ecosystem Approach, divided control into separate monopolies each of which, through a Landscape Approach, focused on particular types of ecosystem services, and the economy itself focused with laser precision on price stability as all exchange rates were fixed—even those hinging on the forward prediction of natural events, regardless of how absurd that is.

In other words, there’s an incredible similarity between the system they seek to implement at present and the one that was—allegedly—discovered on this remote island more than 100 years ago. And the person in charge of this system—the chief—who hired private mercs and retained an exclusive monopoly, can broadly be likened to a tribal (central) banker.

If you at this stage believe that this story is as pure as the driven snow, and that this impeccable alignment with contemporary society is merely a coincidence, then I advise you to seek immediate medical attention.

The reality is that what we currently live through was planned, generations ago.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The price of freedom is eternal vigilance. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.