Triangles

The Human Networks Behind Global Governance

Long before Hans Küng’s 1999 Call to Our Guiding Institutions, the intellectual scaffolding was already in place. In 1945, Aldous Huxley’s The Perennial Philosophy1 argued that the world’s religions share a universal mystical core — a shared ethical framework presented as the natural evolution of understanding rather than a product of coordinated policy.

Around the same time, Alice Bailey described a ‘New Group of World Servers’2 operating through government, religion, and education — an architecture for shaping public consciousness and softening resistance to systemic transformation.

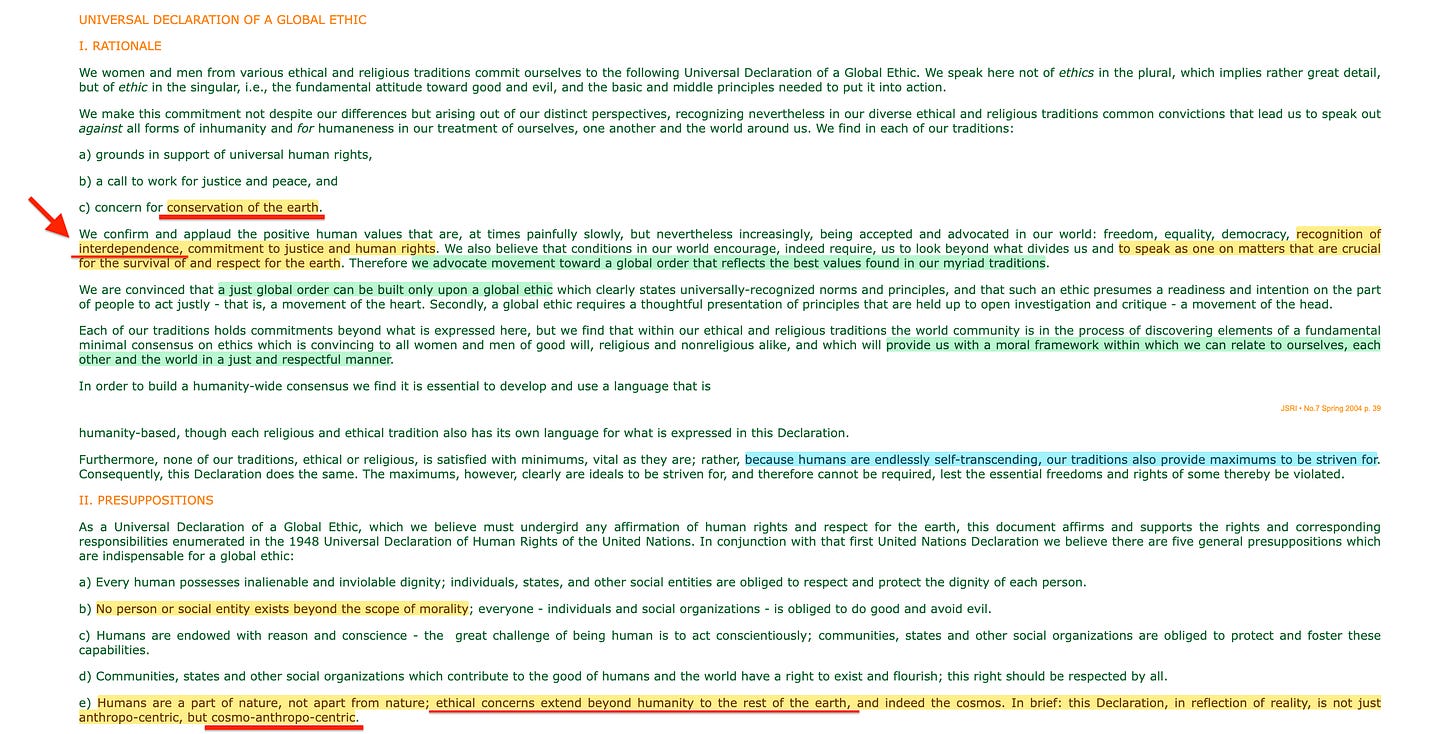

Leonard Swidler later elevated ‘interdependence’ to the status of first principle in his ‘cosmo-anthropo-centric’ global ethic3 published in 1995, thereby supplying the philosophical justification that collective governance is an inevitable necessity. On this foundation, Küng called upon every major sector to embrace the shared Global Ethic he had launched at the 1993 Parliament of the World’s Religions4.

Together, these interventions reframed ethical uniformity as common sense — and made its synthesis appear not merely desirable, but inevitable.

Küng acted as the master architect, designing an eight‑sector model for institutional coordination; Swidler functioned as the philosophical operator, providing the legitimacy framework; Bailey served as the consciousness‑conditioning strategist, embedding government–religion–education alignment. Each fulfilled a distinct role in building an apparatus capable of gradually replacing individual agency with managed collectivism.

Yet, none openly acknowledged that they were laying the foundation for what would later become one of the most sophisticated systems of institutional control in history — channelled through figures presented as moral authorities, legitimised by philosophies that render resistance irrational, and reinforced by psychological conditioning that recasts submission as moral advancement — and refusal to integrate as immoral to the bone.

Executive Summary

This analysis documents the systematic construction of a global institutional control architecture that has replaced democratic governance with expert-managed coordination across all major sectors of society.

The Architecture: Three key figures laid the foundation between 1945-1999: Alice Bailey designed consciousness-conditioning networks operating through government-religion-education triangles; Leonard Swidler provided the philosophical framework making collective governance appear inevitable through ‘interdependence’ theory; and Hans Küng created the comprehensive eight-sector institutional map for coordinating global ethics across religion, government, business, education, media, science, international organisations, and civil society.

The Mechanism: The 1986 UNESCO Venice Declaration legitimised science as the source rather than servant of ethics, enabling a three-tier control system: (1) Global modeling organisations (IPCC, WHO, World Bank, OECD) generate scenario-based ‘moral imperatives’; (2) Ethics networks translate these into sectoral ‘Good Governance’ frameworks; (3) Implementation occurs through measurement chokepoints — OECD indicators, ISO standards, ESG metrics — that gate access to funding, markets, and permits.

The Inversion: What appears to be bottom-up democratic governance is actually top-down model implementation. ‘Ethical leadership’ functions as human interface for predetermined outcomes, while Swidler's interdependence framework makes resistance appear philosophically impossible. The system transforms voluntary ethics into binding compliance through financial and regulatory enforcement mechanisms.

Current Status: The architecture is now complete and operational, with AI ethics and neuroethics protocols enabling real-time technological automation of expert consensus. Democratic decision-making has been systematically replaced by model-derived imperatives implemented through apparently participatory processes.

The Stakes: This represents the successful inversion of democratic accountability, where institutional coordination masquerades as moral progress while eliminating genuine public control over civilisational direction.

Institutional Architecture

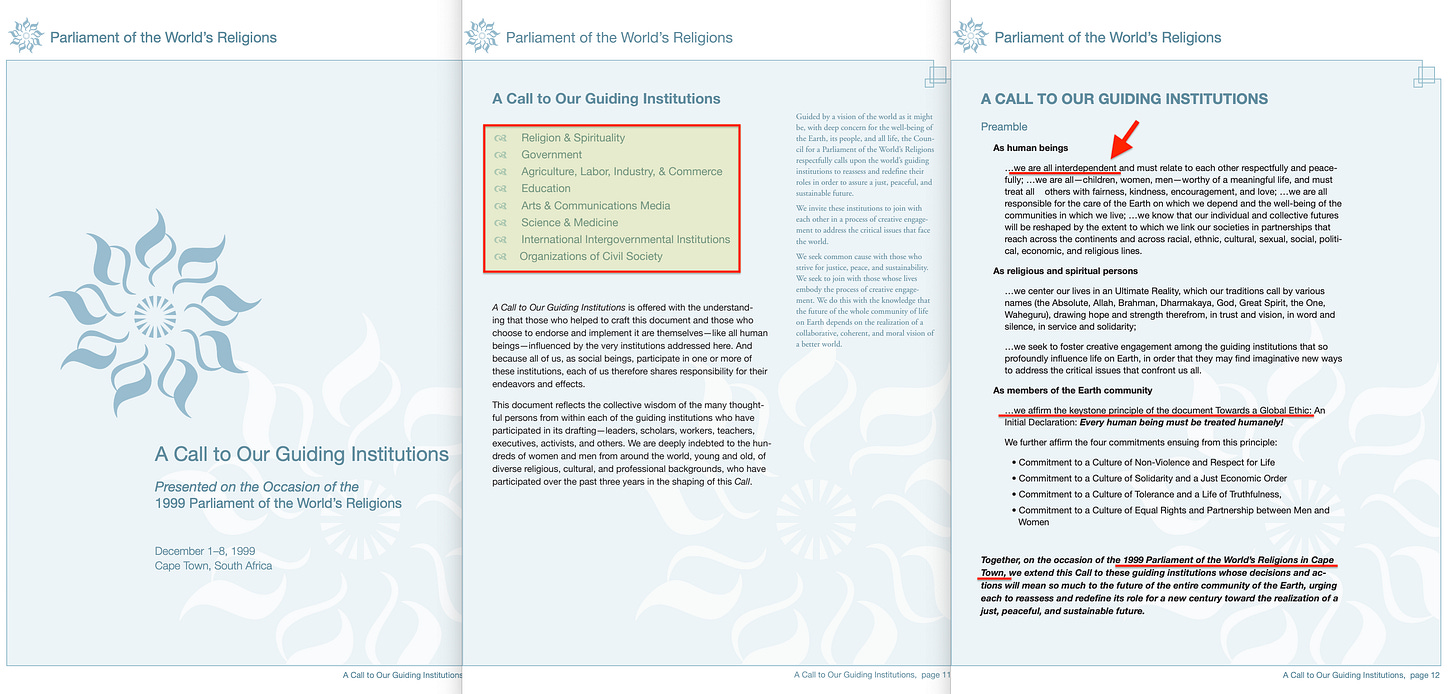

Hans Küng’s most significant contribution was to produce a complete institutional map for coordinating global governance across all major domains of human activity. His 1999 Call to Our Guiding Institutions5 explicitly addressed:

Religion and spirituality;

Government;

Agriculture, labour, industry and commerce;

Education;

Arts and communication media;

Science and medicine;

International intergovernmental organisations;

Civil society.

He urged each to ‘reassess and redefine its role for a new century toward the realisation of a just, peaceful, and sustainable future’ through ‘a shared ethic that clarifies our mutual concerns and common values’.

The genius of the model lay in its creation of multiple, interlocking institutional networks, all operating from the same ethical foundation. Once every sector adopted compatible normative governance protocols, coordination could advance seamlessly — while preserving the public appearance of independent, self-directed institutions.

Philosophical Legitimacy

Leonard Swidler's contribution was providing the philosophical foundation that makes global governance appear necessary rather than imposed. His three-stage progression transforms individual autonomy from a basic right into a dangerous illusion:

Basic Principles: Interdependence

Establishes that individual actions inevitably affect others, making local autonomy seem impossible and collective decision-making in context of expanding spheres of consciousness appear as practical necessity.Middle Principles: Rights and Responsibilities

Transforms rights from constraints on power into conditional privileges that must be ‘balanced’ against expert-defined duties to the collective.Global Ethics

The framework where expert consensus determines what those collective responsibilities actually require in practice.

Swidler's interdependence framework is particularly powerful because it makes questioning global governance seem not just wrong, but literally impossible — if we're all truly interdependent, then global coordination becomes a physical law rather than a political choice.

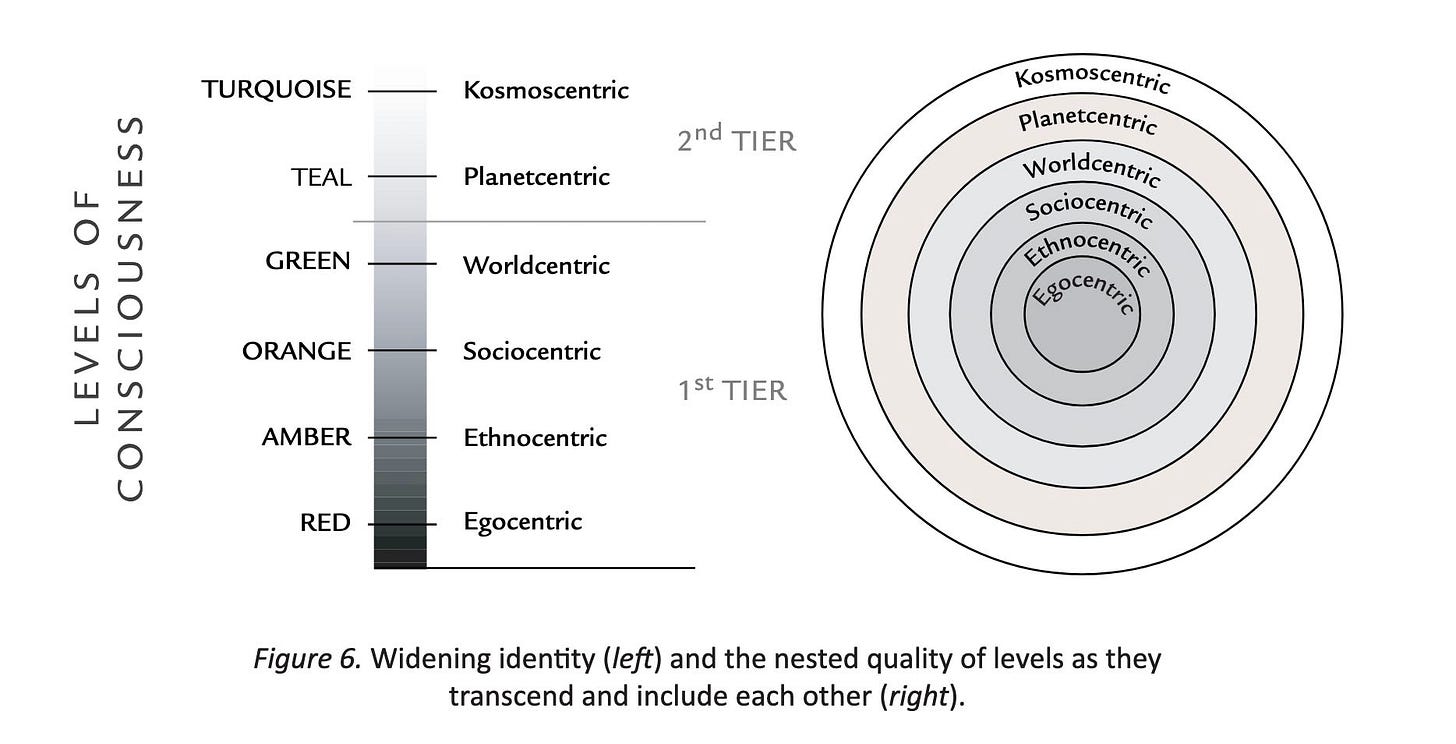

Consciousness Conditioning

Alice Bailey provided the psychological infrastructure that would make populations receptive to institutional coordination and philosophical justification. Her concept of the 'New Group of World Servers' described networks operating simultaneously through government, religion, and education — not as separate influences, but as a coordinated conditioning apparatus — Boulding’s Invisible College, perhaps — designed to reshape human consciousness at the foundational level, in a way not dissimilar to that later witnessed through Ken Wilber’s writings on spheres of consciousness6, while embracing the ‘love’ Swidler explains is fundamentally about consciousness expansion and ‘interdependence’ — ie, collectivism.

Bailey understood that lasting systemic change required more than institutional architecture or philosophical frameworks. It demanded a fundamental alteration in how people think about themselves, their relationship to authority, and their capacity for independent judgment. Her approach involved embedding new thought patterns through the very institutions people trusted most: their governments, their faiths, and their schools.

The genius of her method lay in creating what she termed 'mental preparedness' — psychological conditions where people not only accept increased collective control, but actively desire it. Under proper conditioning, the surrender of individual agency feels like moral evolution rather than political subjugation — resonating with Marc Gafni’s later concept of ‘Unique Self’7. Resistance becomes literally unthinkable because the mental categories necessary for recognising manipulation have been systematically eroded through full spectrum institutional messaging.

Bailey's framework explains why contemporary populations often embrace policies that previous generations would have recognised as obviously tyrannical. The consciousness-conditioning infrastructure she described has successfully created millions of people who genuinely believe that compliance with expert authority — framed as ‘unity of purpose’ — represents the highest form of civic virtue.

Constitutional Moment for Scientific Ethics

The missing keystone came with UNESCO’s 1986 Venice Declaration8, attended by David Suzuki. It declared that the mechanistic worldview of Descartes and Newton was ‘no longer adequate’ and that the misuse of modern technology had become ‘dangerous for the very survival of our species’. Science, it argued, had entered a new systems phase that must integrate with philosophy, culture, and tradition through transdisciplinary methods.

Suzuki carried this forward in his Declaration of Interdependence9, reframing systems science as a moral law: all human and ecological systems are bound in a single web of responsibility. This ethical turn was codified in the 1994 Charter of Transdisciplinarity10, which defined its scope as ‘between, across, and beyond all disciplines’.

Together, these milestones formed the constitutional moment of the Global Modelling → Ethics → Governance pipeline — legitimising science not just as a tool for policy but as the source of binding moral frameworks. Swidler’s interdependence principle made such integration appear natural rather than imposed: if everything affects everything, then expertise must transcend boundaries to manage the whole. The delivery systems were already in place — Bailey’s triangular networks and Küng’s institutional mapping — ready to embed scientifically derived ethics across every sector of society.

A pipeline which is planned to deliver the ultimately death blow to democracy.

The Three-Tier Control Architecture

What emerged post-1986 was an advanced three-tier pyramid with Bailey and Küng positioned as the architects of the receiving structure:

Tier 1 — Global Modelling & Forecasting

Systems models from the Club of Rome, IIASA, IPCC, WHO, World Bank, and OECD produce scenario planning and global-limits frameworks (ie planetary boundaries) that define global risks framed as ‘Universal Moral Imperatives’.

Tier 2 — Ethics & Ethical Leadership

Hans Küng built the comprehensive ethical scaffolding through his eight-sector framework — essentially a complete societal landing pad for global ethics — while Swidler's interdependence framework provided the philosophical foundation that makes collectivist, sectoral coordination appear inevitable rather than imposed, while Alice Bailey provided the earlier prototype emphasising government-religion-education as key consciousness control nodes. Together:

Bailey = moral-ideological hub (Gov–Rel–Edu);

Küng = full sector map (8 nodes) receiving model-derived ethics across all domains.

Tier 3 — Good Governance Implementation

Both frameworks feed into sector-specific ‘Good Governance’ templates:

The system's control operates through three critical measurement architectures that transform ethics into compulsion:

OECD Indicators19 → Public policy benchmarking and national performance rankings

ISO/IFRS-ISSB20/GRI21/SASB Standards22 → Corporate reporting frameworks that gate ESG finance and market access

SDG23/WHO24/IPCC25/IPBES26 Indicators → Treaty targets and national implementation plans with binding commitments

The system transforms ‘voluntary’ soft law ‘ethical’ frameworks into binding compliance through multiple enforcement mechanisms:

Procurement & Grant Conditions

Government contracts and funding require compliance with ESG/sustainability metricsLicensing & Credentialing

Professional bodies enforce ethical codes that align with global frameworksListing & Insurance Requirements

Market access depends on sustainability reporting and risk assessmentsBanking & ‘De-risking’

Financial institutions withdraw services from non-compliant sectors or activitiesPlatform Access & Moderation

Digital platforms enforce ‘community standards’ derived from expert consensusDe-funding & NGO Accreditation

Civil society organisations lose status and funding for deviation from approved positions

Swidler's interdependence framework provides the philosophical justification for this enforcement architecture — individual non-compliance allegedly harms the collective, making penalties appear protective rather than punitive. When rights depend on responsibilities to an interdependent whole, sanctions become moral necessities rather than authoritarian overreach.

This isn’t speculation. Here are two surgical case studies:

IPCC → NDCs (2015-present):

Climate models generate ‘carbon budgets’, interdependence frameworks establish ‘fair share’ responsibilities based on collective impact, resulting in Nationally Determined Contributions27 that, in many jurisdictions, become binding through national climate laws and budget allocations.ISSB → IOSCO → Market Gates (2023– ):

ISSB S1/S228 set the global baseline for sustainability disclosure; IOSCO’s 2023 endorsement triggers adoption by securities regulators and exchanges. Result: disclosure becomes a condition for listings, underwriting, insurance, and some procurement — turning ethics-framed metrics into de facto market compulsion.

The Cybernetic Extension

Modern implementation leverages technological automation:

AI Ethics: OECD AI Principles29 and the IEEE 7000-series30 (IEEE Std 7000-2021) create real-time governance bridges from expert consensus to algorithmic enforcement

‘Interdependence’ makes this technological integration appear inevitable — if human decisions inevitably affect complex global systems, then algorithmic management becomes a practical necessity for handling the complexity rather than a form of technological control

Neuroethics31: UNESCO's neurotechnology guidelines establish frameworks for direct cognitive modification aligned with institutional priorities

If ethics truly emerged bottom-up through local deliberation — and if indicators were optional rather than tied to funding and permits — the inversion claim would collapse. Evidence would include communities successfully developing alternative ethical frameworks without expert validation, institutions thriving while rejecting global indicators, and policy decisions that contradict expert consensus without facing systematic sanctions.

Yet, they don’t.

Real-World Triangular Networks

These concrete institutional examples demonstrate how the Bailey-Küng framework has been systematically implemented through specific organisational structures that complete the sphere of social control within ‘Good Governance’. Swidler's interdependence principle makes this matrix coordination appear necessary rather than manipulative - since all sectors are inevitably connected, coordination becomes a practical requirement for system stability rather than institutional capture:

1. Government – Business – CSO

The classic stakeholder capitalism model legitimising corporate-state coordination through NGO participation.

Organisations: World Economic Forum, OECD partnerships, UN Global Compact

Examples: ESG investment frameworks, corporate sustainability partnerships, ‘civil society’ advocacy for business-friendly regulations

The OECD's Special Role as Measurement Control Center: Once the OECD operates within this triangle, it transcends mere ‘policy dialogue’ to become indicator and metrics governance:

The OECD defines and harmonises the statistical frameworks used across sectors

These indicators become the measuring stick for ‘good governance’ in each domain

Because business and CSOs adopt the same metrics (via ESG, SDGs, impact reporting), government policy becomes effectively locked into the same model outputs

This creates a data-driven compliance architecture that feeds directly back into the global modeling → ethics → governance pipeline

Critical Insight: The OECD's role represents the measurement choke point — whoever controls the indicators controls the definition of success, and thus controls the ethics. This transforms the triangle from a policy forum into a cybernetic feedback system where ‘progress’ is measured exclusively by predetermined metrics derived from Tier 1 global models, making alternative definitions of success literally unthinkable within the system.

2. Government – Religion – Education

Implementing the three-phase consciousness transformation that makes populations psychologically ready for global management.

Organisations: World Goodwill networks, UNESCO religious/educational forums, interfaith climate initiatives, values-based education curricula

Examples: National education policies incorporating religious values, faith-based policy advocacy, educational curricula promoting spiritual/ethical frameworks

Removing Higher Truth: Religious institutions are co-opted to abandon transcendent moral authority in favor of ‘planetary stewardship’ and ‘collective responsibility’. Educational curricula teach that ethics are subjective constructs rather than universal truths. Government policy treats ‘human dignity’ as a concept to be defined by expert consensus rather than an inherent right.

Institutional Authority: The triangle coordinates to position dissent as ignorance or extremism. Religious leaders condemn questioning of ‘scientific consensus’ as morally irresponsible. Educational institutions frame critical thinking about official narratives as ‘misinformation’ or ‘conspiracy thinking’. Government agencies work with both sectors to ensure unified messaging on climate, health, and social issues.

Compliance Infrastructure: Religious institutions provide moral legitimacy for surveillance and compliance systems. Educational institutions condition students to accept monitoring as normal and beneficial. Government provides the legal framework for emergency powers that bypass traditional democratic processes.

This triangle doesn't just coordinate policy — it fundamentally reshapes how people understand the relationship between individual conscience and institutional authority, making the transition from democratic self-governance to expert management feel like moral evolution rather than political capture.

3. Government – Science – Media

Manufacturing expert consensus and controlling public information about ‘scientific’ policy issues.

Examples: IPCC, WHO communications, national science communication councils

4. Government – Media – Education

Coordinating public messaging and narrative control through official channels.

Examples: National climate campaigns32, pandemic communication strategies33, ‘media literacy’ education34

5. Business – Religion – CSO

Mobilising religious authority to legitimise corporate ESG frameworks and stakeholder capitalism.

Examples: FaithInvest35, Religions for Peace36 corporate-NGO partnerships

6. Business – Media – CSO

Coordinating corporate messaging through media partnerships and NGO advocacy.

Examples: Responsible Media Forum37, WEF Media/ESG coalitions38

7. International Organisations – Business – Government

Global economic coordination that supersedes national democratic decision-making.

Examples: WTO/IMF/World Bank governance structures.

8. International Organisations – Religion – CSO

Mobilising religious institutions for UN sustainability goals through civil society coordination.

Examples: UNEP Faith for Earth39, Parliament of the World's Religions climate initiatives40

9. Science – Media – Education

Embedding scientific authority into educational curricula and public discourse.

Examples: UNESCO Science Communication41, IPCC school outreach programs42

The Cybernetic Extension Falsification Test

Automation — via OECD AI Principles43 and UNESCO’s neurotechnology44 work (process ongoing 2024–25) — enables ‘live’ transmission of expert consensus into systems that moderate content, guide medical decisions, and steer behaviour. If neurotech/BCIs mature, governance could channel consensus into cognitive nudges, raising acute accountability questions.

There are internal fights and reversals; the claim here concerns structure and incentives, not unanimity.

The case for indicators. Harmonised standards do offer benefits: comparability, coordination, and reduced regulatory arbitrage. But the measurement choke‑point centralises power by fixing which metrics matter, how success is defined, and who sets the yardstick—excluding alternative frameworks for progress and wellbeing.

Falsification test. The inversion claim fails if ethics arise bottom‑up via genuine deliberation and if standards are optional rather than gates for funding and permits. Evidence would include communities thriving with alternative ethics; institutions succeeding while rejecting global indicators; policies deviating from expert consensus without systematic sanctions. It would also include viable institutions operating without cross‑sector coordination; demonstrable cases where individual actions do not materially affect others; and communities rejecting interdependence as foundational while remaining functional.

Critical Insight: All these triangular networks operate under ‘Good Governance’ rhetoric, consistently framed as ‘Ethical Leadership’45 implementing ethical imperatives derived from global modeling. Each node operates under its sector-specific ‘Good Governance’ code, but all are harmonised to the overarching ethical directives flowing from Tier 2. This creates apparent institutional diversity while ensuring substantive coordination toward predetermined outcomes.

The Ethical Leadership Initiation System

‘Ethical leadership’ operates less as moral excellence than as initiation and selection, filling key posts with individuals pre‑aligned to the framework.

Selection premise. Under interdependence, only leaders who treat autonomy as illusory are deemed capable of managing complex systems; those who insist on independent decision‑making are framed as cognitively unfit for complexity.

Stage 1: Ethics from Global Modelling. Values are preset by model outputs (climate, health, biodiversity, AI risk, economic sustainability). Indicator data are compared to reference ranges; deviations are deemed ‘bad’, creating imperatives to drive metrics back within range.

Stage 2: Good Governance Institutionalisation. The global ethic becomes the benchmark across sectors. Bodies such as ISO, OECD, WHO, and BIS embed these ethics in standards, rules, and performance measures. Non‑adherence is penalised (often economically); adherence is rewarded (from reputational boosts to preferential access).

Stage 3: Initiate Selection & Training. Leadership pipelines prioritise alignment over competence. Fellowships and formation programmes serve as initiation pathways:

WEF Young Global Leaders: Future political and business leaders shaped by stakeholder capitalism frameworks

Rhodes Scholars: Academic elites trained in global governance perspectives

Aspen Institute programs: Cross-sector leadership development in ‘shared values’

UNESCO chairs and fellowships: Educational leaders aligned with global citizenship frameworks

Faith-based leader exchanges: Religious authorities coordinated through interfaith climate and sustainability initiatives

Closed loop. Over time, only initiates reach positions where they could influence the ethic. Bailey’s triangles pioneered this spiritually; Küng’s eight sectors extended it across society.

‘Ethical leadership’ thus becomes gatekeeping for orthodoxy, masking uniformity beneath the appearance of diversity.

The Democratic Illusion and Complete Inversion

The system appears participatory: ‘objective’ analysis (Tier 1), ‘inclusive’ deliberation (Tier 2), ‘democratic’ implementation (Tier 3). In practice, the same networks populate all three layers; ethics are predetermined by modelling assumptions, and implementation follows regardless of public input.

Instead of Public Values → Ethical Frameworks → Technical Implementation,

we get Elite Models → Elite Ethics → Elite Governance.

Swidler’s interdependence makes this appear philosophically necessary: if every action implicates the whole, local autonomy becomes reckless illusion.

The Venice Declaration legitimised the inversion by elevating science from servant to source of ethics. Hence why questioning climate models is treated as moral deviance: the ethical framework itself has been derived from those models.

‘Ethical leadership’ operationalises the system by staffing it with people who experience institutional loyalty as independent moral reasoning — while incentives reliably align ‘authentic’ ethics with predetermined conclusions.

The Cybernetic Completion

The convergence of AI Ethics frameworks and neuroethics protocols now enables real-time technological automation of this moral authority system. When expert networks update their consensus, those changes can propagate immediately to AI systems that moderate content, guide medical decisions, and influence behavioral recommendations — without public awareness or democratic input.

Enhanced humans will receive neural programming guided by the same dynamic expert consensus that shapes their information environment, ensuring complete cognitive alignment with institutional priorities. The system achieves total control through what subjects experience as personal empowerment and intellectual advancement.

Within Swidler’s interdependence framework, such completion is framed as optimisation rather than tyranny: if cognition affects collective outcomes, aligning thinking to consensus becomes ‘quality assurance’ rather than control.

Conclusion: Recognising the Architecture

Bailey’s ‘stage of the Forerunner… until 2025’, Küng’s eight‑sector Global Ethic, and Venice’s scientific authority have converged into a measurement‑driven control system where ‘ethical leadership’ is the human interface for coordination that outpaces democratic consciousness.

Resistance becomes heresy, not through crude suppression but by controlling the indicators that define success and the ethical frameworks that confer legitimacy. Understanding this structure reveals how independent institutions are synchronised through shared metrics and mandates derived from modelling rather than democratic deliberation.

True ethical leadership would be:

Accountable to democratic publics rather than self-legitimising expert networks

Encourage genuine moral reasoning rather than compliance with scientifically-derived frameworks

Recognise that ethics must constrain rather than justify institutional power.

The choice before us is whether ‘ethical leadership’ will serve democratic accountability or continue functioning as the human face of technocratic control disguised as moral progress.

Understanding this architecture requires seeing the complete hierarchy from bottom to top. At the implementation layer, ‘Good Governance’ templates create the appearance of local democratic decision-making while systematically channeling outcomes toward predetermined frameworks. The ethics layer — Bailey's triangular networks and Küng's sectoral mapping — provides human interface and moral legitimacy, ensuring that ‘ethical leaders’ experience their institutional loyalty as independent moral reasoning. But above both layers sits the global modeling apparatus: IIASA generating systems scenarios, OECD defining performance indicators, and ISO establishing universal standards that transform planetary boundaries into moral imperatives flowing downward through the entire system. What appears to be bottom-up democratic governance is actually top-down model implementation, with every layer below serving to operationalise the outputs of global modeling through apparently participatory processes.

The 1986 Venice Declaration made this inversion possible. By declaring the old mechanistic view ‘no longer adequate’ and licensing transdisciplinary authority ‘beyond’ disciplines, it legitimised science as a generator of ethics — with Bailey’s networks and Küng’s map waiting to receive them.

Every choke‑point, every enforcement lever, and every ‘triangle’ now serves a single mandate: that ‘black box’ model outputs determine ethical frameworks for civilisation. Swidler’s interdependence supplies the final aura of inevitability: if everything is connected, expert management is the only rational alternative to chaos.