There are moments in history which, when viewed in the light of decades, not years, reveal themselves as decisive inflection points. The assassination of John F. Kennedy was one such — a moment that arrested not just a presidency, but an ideological resistance to the rise of technocratic control.

And this new post-assassination trajectory might well have led to the development of the 7th floor shadow state1.

John F. Kennedy entered office with a mix of Cold War realism, liberal idealism — and Council on Foreign Relations representation. Among his cabinet was Robert McNamara2, a CFR member3 and former Ford Motor Company executive, who became Secretary of Defence.

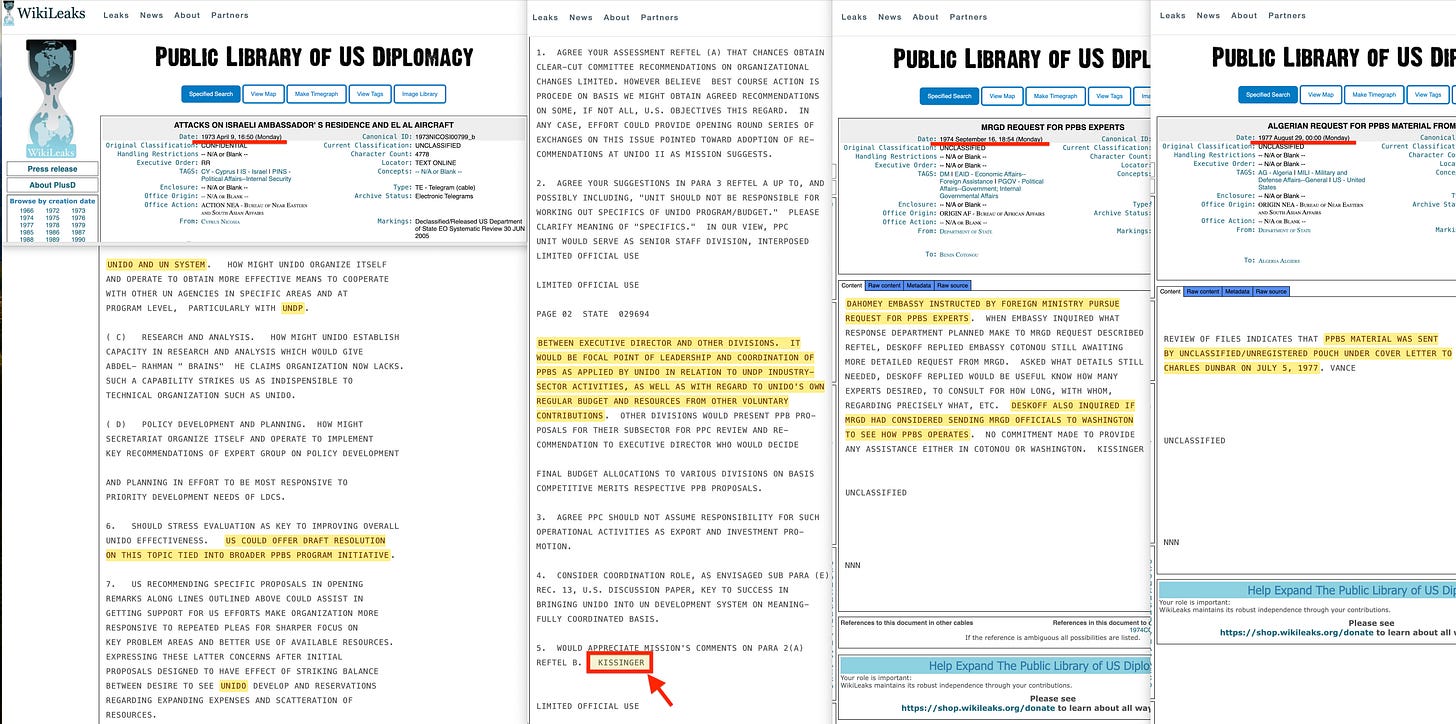

Almost immediately, McNamara set out to implement a Planning, Programming, and Budgeting System4 (PPBS) across the Department of Defense. PPBS was designed to track every stage of a process by tracking both numerical inputs and measurable outputs, creating a feedback loop to evaluate efficiency in terms of goal delivery.

In essence, PPBS kept a tight leash on metrics5. Outputs were no longer vague deliverables — they were precise, trackable, and reproducible. And because of this, each output could now serve as the input for the next stage, and operations could be sequenced into a continuous chain of feedback and correction.

This enabled, theoretically, a form of long-term planning grounded not in abstract projections, but in real-time system performance, backed by detailed tracing of the delivery of objectives. What consequently began as a defence budgeting method would soon become the model for technocratic governance at scale.

The CIA was next in line for full PPBS rollout — but then disaster struck. The Bay of Pigs invasion was a total failure, and in the aftermath, John F. Kennedy purged the top leadership of the Agency. Among the four senior officials removed was Robert Amory, Jr., a key figure in introducing systems-based planning to intelligence — though his role often escapes notice. Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. protested, attempting to protect Amory — but his objections were in vain, with Amory being let go on the 15th of April 1962. This, almost certainly, was not according to plan, as the two men had also cooperated on a ‘World Congress for Freedom and Democracy’6, likely a manipulative attempt at reframing liberal western democracy around stakeholder governance.

This sequence of events was previously discussed in The Fourth Casualty.

However, despite the early promise of McNamara’s PPBS, JFK’s faith in the system began to erode during the Cuban Missile Crisis7. At a critical juncture, McNamara’s much-vaunted ‘wonder system’ recommended a series of precision strikes on Soviet missile installations in Cuba. But Kennedy hesitated — and rightly so. As later revealed, the Department of Defense lacked the full intelligence picture, and such strikes would likely have triggered massive Soviet retaliation.

That moment proved decisive. JFK came to understand the limits of systems analysis — its reliance on incomplete data, and its preference for computational modelling over political deliberation — and from that point forward, he began to distance himself from the broader rollout of systems theory within government.

Kennedy’s foreign policy increasingly diverged from the hard-edged interventionism favoured by key people in the Department of Defense and CIA. His 1961 fallout with the Agency following the Bay of Pigs — culminating in the dismissal of Allen Dulles, Charles Cabell, Richard Bissell, and Robert Amory, Jr. — reflected more than operational failure; it marked a philosophical rift.

While Kennedy did not reject data-driven planning outright — he did, after all, retain McNamara — he became increasingly resistant to the wholesale integration of these methods across the federal government. For Kennedy, politics was not reducible to computational modelling, but an endeavour grounded in human judgement, intuition, and contextual deliberation — a stance that placed him in growing tension with the logic of postwar technocracy.

Kennedy’s National Security Action Memoranda from 1962–63 — particularly NSAMs 55–5789 and the later NSAM 26310 (the Vietnam withdrawal plan) — signalled a clear shift toward reducing covert influence. Equally revealing was the rejection of proposals like the World Congress for Freedom and Democracy backed by Arthur Schlesinger Jr. and Robert Amory Jr., which would have established a supranational trisectoral civic management infrastructure modelled on civil society capture and ‘expert-led’ consensus mechanisms, well outside of democratic capacity.

Kennedy recognised the dangers of elite-managed internationalism cloaked in democratic rhetoric. In that light, it’s especially telling that he had Robert Amory Jr. bugged in February 196311 — a highly unusual move, made all the more striking by the fact that Kennedy expressed personal interest in his case.

Yet Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963 abruptly cut short his challenge to the emerging structures of centralised, technocratic governance. What followed was not merely a new presidency, but a major shift in institutional direction — and pace.

Under Lyndon B. Johnson, the PPBS system — previously confined to McNamara’s Defense Department — was extended to all executive agencies in 196512. Where Kennedy had approached central planning with caution, Johnson embraced it with enthusiasm. Systems analysis became the common language of federal administration, embedding rationalised, metric-driven oversight into domains such as education, health, welfare, and environmental policy.

What drew less public attention, however, was a flurry of executive orders issued shortly after the escalation of the Vietnam War during Johnson’s second term. In hindsight, these are remarkable, as they granted the Federal Reserve unprecedented visibility into the financial flows of the nation’s largest banks. Behind the scenes, monetary authorities were quietly gaining structural oversight that would lay the groundwork for deeper integration between fiscal policy, banking, and national planning.

This was discussed in depth in The Missing Link.

The latter point becomes especially significant in light of a controversial document previously discussed on this Substack: Silent Weapons for Quiet Wars. That text outlines a methodology for economically ‘shocking’ the American population and then measuring the reverberations throughout the economy — a concept that aligns suspiciously well with the dynamics of the 1973 oil shock.

But there’s a deeper problem at play.

Such economic reverberations could not have been tracked or modelled with any precision unless the authors had access to real-time, granular fiscal flow data — precisely the kind of access enabled by the executive orders issued under LBJ. These orders furnished the Federal Reserve with an unprecedented window into the operations of major U.S. banks, creating the infrastructure for what we might now call economic telemetry.

And this, then, hints at who would have even been capable of discussing such a topic in the first place: those with operational control over the Federal Reserve.

Soon after LBJ came to power, he reversed JFK’s withdrawal from Vietnam (NSAM 263) through NSAM 28813, and also leaned heavily on people like Walt Rostow — a promoter of modernisation theory and centralised economic planning — to shape U.S. development strategy abroad. Domestically, Johnson’s Great Society initiatives expanded federal insight into civil life, especially given initiatives such as his war on poverty14, addressed by and large through statistical indicators.

In fact, much of the Great Society’s15 implementation relied on indicators generated through surveillance data and computational forecasting — precisely the kinds of instruments made possible by the broad rollout of PPBS across government agencies. In parallel, it quietly normalised the increasing presence of the third-party ‘expert’ mediator — technocrats, consultants, and data analysts — into the core of governance, and thus, entirely outside the scope of democracy.

The technocratic architecture was being constructed under the banner of compassion and social justice, with surveillance-driven data systems used to determine which populations were ‘deserving’ of intervention or financial aid. In effect, ethics and empathy were operationalised through metrics, and the groundwork was laid for a model of governance that would become increasingly algorithmic and managerial in the decades to come16.

And as McNamara left the Department of Defense, his next position with the World Bank proved yet another opportunity for the integration of PPBS17 — but this time slowly rolled out through its sister agencies18, such as UNIDO19 and the UNDP20 in the early 1970s, while the 23 May 1972 agreement quietly fused socialism and capitalism under the environment-based indicator, created through UNEP GEMS surveillance data and modelled by the IIASA.

By the 1980s, the core mechanisms of PPBS were integrated into the emerging framework of New Public Management (NPM)21. A pivotal moment came in 1984, with the publication of R. Edward Freeman’s Stakeholder Approach22, which provided the ideological background for a shift in public administration.

Under NPM, performance targets and quasi-market mechanisms were introduced into the public sector. Agencies were now expected to ‘compete’, and were rewarded or penalised based on key performance indicators23 (KPIs). Governance was reframed in managerial terms: efficiency, responsiveness, and stakeholder satisfaction replaced deliberation, public accountability, and civic judgement. And — not least through McNamara’s World Bank — this system was increasingly introduced globally.

This evolution continued with the rise of Results-Based Management (RBM)24, a framework that evaluated entire institutions based on their alignment with predefined goals. Major global organisations — including the United Nations and the World Bank — adopted RBM to manage complex partnerships by tracking progress toward specific targets, such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and, later, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)25.

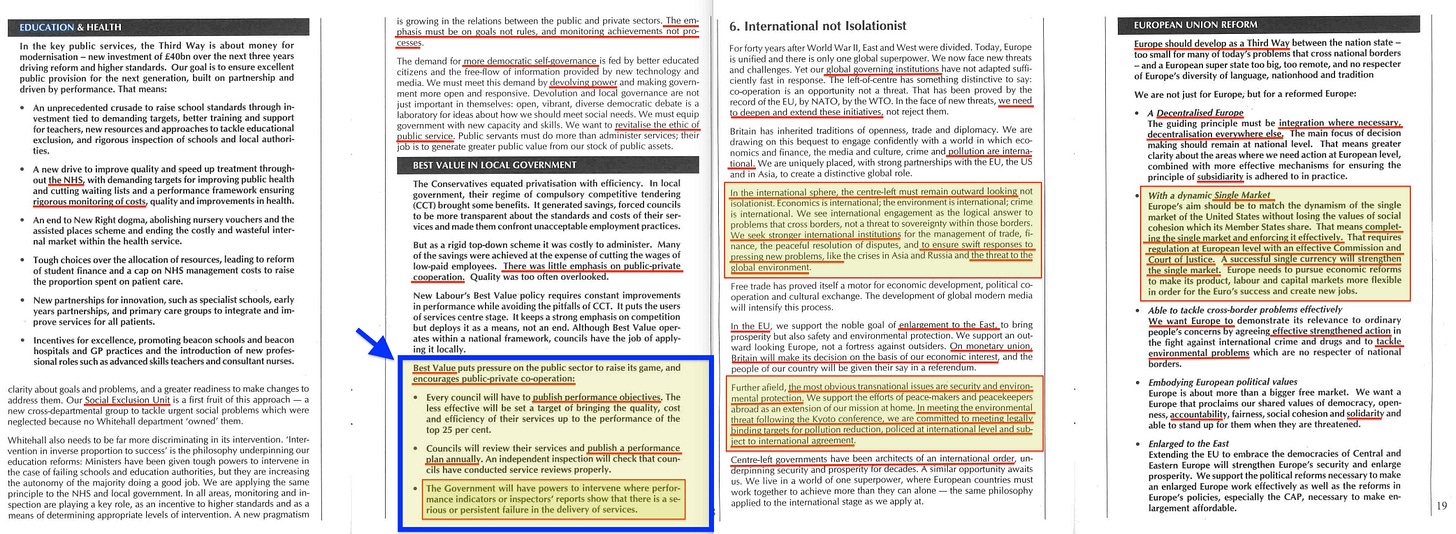

But this same mechanism also found domestic application — notably in Tony Blair’s 1998 Fabian Society pamphlet, The Third Way. Blair proposed that local councils be assigned specific targets, with performance measured against those goals. Failure to meet these could result in financial penalties, effectively placing councillors in a fiscal straightjacket: comply with the centrally defined objectives, or explain to residents why services like elderly care or policing had to be cut.

Post-Blair, Gordon Brown frequently invoked the idea of the ‘Good Society’26 — a concept that echoed Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, but now updated with more advanced computational tools. Like its predecessor, Brown’s vision relied heavily on indicator-based governance, enabled by systemic surveillance and predictive modelling. What had once been long-range planning through bureaucratic systems was now being carried out by data-driven algorithms, offering the appearance of moral progress while deepening technocratic control.

This gave rise to what can best be described as Target-Based Governance2728 — an Indicators Regime, where measurable indicators are no longer just tools for evaluation but become instruments of governance themselves. Systems such as the SDGs29, ESGs30, and HDI31 function through indicators as input data for cybernetic feedback loops, actively shaping policy, finance, and public narrative.

The alignment with contemporary policy — particularly in areas like climate action, sustainability, and biodiversity — should by now be unmistakably clear. Governance will increasingly be executed not through law or deliberation, but through metrics.

The culmination of this entire trajectory is Digital Twin simulation governance, powered by advanced AI. This model enables real-time adjustment of systems through global surveillance, artificial intelligence, and indicator-based targets that determine whether a decision is considered ‘ethical’ or not, where this determination is made relative to a stated objective. If an action aids in the delivery of said objective, then it per definition is ‘ethical’ — much like Paul Carus in 1893 first stated that:

Truth, accordingly, is a description of existence under the aspect of eternity.

This quote can be located in his book, The Religion of Science32.

These ‘ethical’ determinations are then filtered through a Cultural Framework — integrated into education, the arts, science, and even religion. At the philosophical root lies Hermann Cohen, whose notion of infinite judgement justifies the codification of ethics into binding legislation — a mechanism historically associated with systemic abuses committed under the banner of moral necessity.

Yet at its core, this system marks a shift: from static planning to dynamic, cybernetic management of ecosystems, economies, and societies — governed not by law or democracy, but by feedback, simulation, and code — and what I previously labelled Cybernetic Thomism.

This development, when fused with AI, leads directly into what I previously titled Cybernetic Empiriomonism — a system in which AI doesn’t merely respond to human input, but actively tailors the returned information to the individual, with an example presented below which outlines various ChatGPT summaries of a substack post as though it was published by a number of different news media, thus illustrating how incredibly manipulative this technology truly can be. And though this rests under the banner of AI Ethics and ‘Safety’, it eventuallly evolves into something far more sinister: the integration of man and machine through brain–computer interfaces (BCIs) — a stage that Huxley and others foresaw and named: Transhumanism33.

Ergo, what began with McNamara’s early-stage predictability — the chaining of processes for long-term planning — gradually became continuous, global, automated, and ‘ethical’. It evolved into target-based accounting, outcome-based accountability, strategic foresight, and eventually into the framework now known as Earth Systems Governance: a model of infinite complexity-based feedback for climate, biodiversity, and even human health.

And this all sprang to life under the banner of ‘Spaceship Earth’ in the mid-60s, with the 1968 UNESCO Biosphere Conference indicating a sharp acceleration of this initiative.

Alongside this came management information systems, the transformation of global surveillance into normalised indicators, the rise of planetary monitoring platforms, and the deployment of AI simulation models — not just to observe, but to predict and correct. These models inform adaptive management, where outputs are continually adjusted in real time to maintain system equilibrium.

Consequently, McNamara’s budget focus was never just about money. It became policy + ethics + data, stitched together into a global feedback infrastructure — designed not to govern by law, but to manage by simulation.

In other words, the trajectory has always been clear: a progressively tighter coupling between systems theory, moral governance, and technological convergence. And there was really only one man that took a stand against this development. The same man who was assassinated in Dallas, in November 1963.

To be continued.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The price of freedom is eternal vigilance. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.