The Missing Link

Beginning with Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring1, the 1960s witnessed an explosion of activity in the realm of environmentalism. But what few realise is that much of Carson’s inspiration was drawn from Frank Egler, who had already begun to articulate the concept of the Total Human Ecosystem2—well before Zev Naveh’s later developments in the same vein.

It suggests that the story, as commonly told, is not quite all it seems. And as it happens, this particular thread goes rather deeper than most would imagine.

Zev Naveh’s later articulation of the Total Human Ecosystem essentially describes a post-capitalist world stripped of human liberty—where man is cultivated as a species like any other, managed within a technocratic ecological system. In this schema, a select few—the elite of the elite—administer total control through full-spectrum systems theory, advanced AI, and adaptive management in a global surveillance grid saturated with Digital ID, CBDCs, 15-minute cities, social credit systems, vaccine passports, and omnipresent cultural engineering. It is a dystopian vision that not even Huxley or Orwell quite managed to capture—though it aligns with Teilhard’s vision of the Omega Point, the final convergence of mind and matter. Whether you survive the journey to that promised endpoint, however, is another matter entirely. You may well be culled along the way—for the ‘common good’, of course.

And while it may sound far-fetched, only a few missing pieces had long held me back from stating this outright. I have now located enough evidence—of sufficient quality—to confidently synthesise two previously parallel timelines explored on this Substack.

The first begins with Julius Wolf in 1892, moving through Eduard Bernstein (1899), Leonard S. Woolf (1916), and Alfred Zimmern (1919–1926), whose work fed directly into the blueprint for the RIIA, the League of Nations, and later UNESCO and the United Nations. In the 1970s, the NIEO and the ‘Third System’ quietly embedded NGOs into the heart of G77 development governance, laying the groundwork for Our Common Future (1987), which injected systems theory into the mainstream of global management. That trajectory culminated in the 1992 Earth Summit’s Agenda 21—an explicit blueprint for public-private governance ‘for the common good’, mediated through General Consultative Status NGOs and institutionalised under Wolfgang Reinicke’s trisectoral model between 1998–2000.

But all of this leaves open the deeper question of why. The capitalist and socialist blocs were ostensibly at odds. The Cold War framed them as antagonistic forces—yet their reconciliation came with surprising speed. Gorbachev, in 1987, openly called for defusing the East–West divide through a shared focus on environmentalism. This pivot aligns with the earlier, often overlooked May 23, 1972 US–USSR Agreement on Environmental Protection. And it finds further corroboration in Zbigniew Brzezinski’s Between Two Ages, which prefigured the Trilateral Commission—a forum that helped normalise the integration of NGOs into global governance, all under the banner of the ‘common good’.

This is not ‘conspiracy theory’. It is sourced, documented, and leads—ineluctably—to the conclusion that Anatoliy Golitsyn was correct. Perestroika was not a liberalising retreat, but the final stage of a long-term strategic deception that began under Khrushchev.

Golitsyn argued that Lenin’s New Economic Policy was being revived—evident in perestroika—but never fully articulated its ultimate purpose. Brzezinski, however, did. Ecology was to be the common concern—the rallying point for global integration. Science would lend the illusion of neutrality and objectivity—delivered through global models, predictive simulations, and systems analysis. Moiseev, despite acknowledging that such models could not accurately predict weather nor long-term trends at all, insisted they were essential for planetary planning.

From there, the logic becomes hard to ignore: NGO-driven global environmental governance, legitimised by consensus, orchestrated through General Systems Theory (deriving from Alexander Bogdanov), and operationalised via scientific modelling (IIASA, IPCC), all underpinned by ‘market-based mechanisms’ for the monetisation of nature—just in time for the 1992 Earth Summit.

This not only unified East and West under a shared objective, but also aligned key mechanisms dating back to Wolf (1892), Bernstein’s public–private model (1899), Woolf’s Fabian blueprint for global governance (1916), Zimmern’s adaptation of that model for the League of Nations (1919), and the eventual creation of the BIS in 1930, based on Wolf’s gold-clearing concept. The RIIA, meanwhile, laid the intellectual groundwork for the monetary frameworks that later legitimised Keynes’s General Theory in 1936, paving the way for Bretton Woods (1944) and the formal founding of the UN in 1945.

Through Woolf’s architecture, the League of Nations created a channel for international organisations to quietly erode sovereignty under the guise of cooperation. This trend accelerated through the rise of neoliberal trade regimes in the 1990s, as tariff elimination and labour mobility forced legislative harmonisation. Upon the League’s founding in 1919, the ILO (focused on labour) and the International Research Council (focused on science) were created—early examples of governance institutions deliberately removed from democratic accountability.

The IRC, however, found even minimal national oversight intolerable. It was dissolved and replaced in 1931 by the International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU)—free from state interference and soon funded by philanthropic foundations. From that point forward, the ICSU helped manufacture flexible, politically expedient scientific ‘consensus’ aligned with elite strategic aims.

By 1969, ICSU helped establish SCOPE, who with further foundation funding in turn developed the conceptual foundations for UNEP’s Global Environmental Monitoring System (GEMS). By 1974, GEMS had already incorporated public health surveillance—justified on the basis that “man is part of the environment.” Yet this process had already begun in 1946, when ICSU and UNESCO were effectively fused through figures such as Victor Kovda and Joseph Needham. Kovda, in particular, was pivotal, becoming president of SCOPE in 1973 and overseeing the design of the environmental surveillance grid later implemented by Maurice Strong.

Even before UNESCO, the 1941 Science and World Order conference in London—held during WWII—mapped out a vision of scientific socialism. It included explicit proposals for an International Resources Office, later echoed in early UNESCO meetings by Julian Huxley and J.D. Bernal. After departing UNESCO, Huxley co-founded the International Union for the Protection of Nature in 1948 (now the IUCN), which became the apex institution of planetary governance—renamed in 1956 as the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. That renaming, notably, coincided with Khrushchev’s consolidation of power.

And that, in turn, prompts a few questions.

Is it possible to unearth supporting evidence for what might rightly be called the Green Perestroika Deception—a convergence that synthesises the fall of the Iron Curtain, the rise of environmentalism, the corruption of global governance through the strategic insertion of NGOs into international institutions under the guise of ‘serving the common good’, and the monopolisation of finance?

Could this arc plausibly extend to the 2023 Fabian Society report In Tandem, which openly calls for a merger of the Bank of England, the UK Treasury, and select NGOs?

A merger which, if realised, would amount to a soft coup—shifting power over taxation and spending away from elected government and toward unelected NGOs and ‘independent’ monetary authorities. Worse still, it would lay the structural foundations for a coming Social Credit System—tied to Digital ID, carbon-backed CBDCs, 15-minute cities, and vaccine passports requiring continual updates. All, naturally, under the banner of ‘partnership’, ‘resilience’, and the ever-elastic ‘common good’—with environmentalism as the moral pretext, and individually tailored fiscal controls, enforced through programmable CBDCs and spatial-restriction frameworks like the 15-minute city.

And as it happens… yes. Yes, such evidence—rooted in the Khrushchev-era transformation—most certainly exists.

Let’s begin with Lyndon B. Johnson—because something remarkable happened as he took the reins following JFK’s assassination in November 1963. It was subtle, but visible, most clearly through the barrage of executive orders he quickly began signing.

Yes, Kennedy had spoken the language of environmental protection. He had even passed the Clean Air Act of 1963 into law. But it was under Johnson that the agenda was supercharged—alongside executive orders that gradually handed more power to the Federal Reserve.

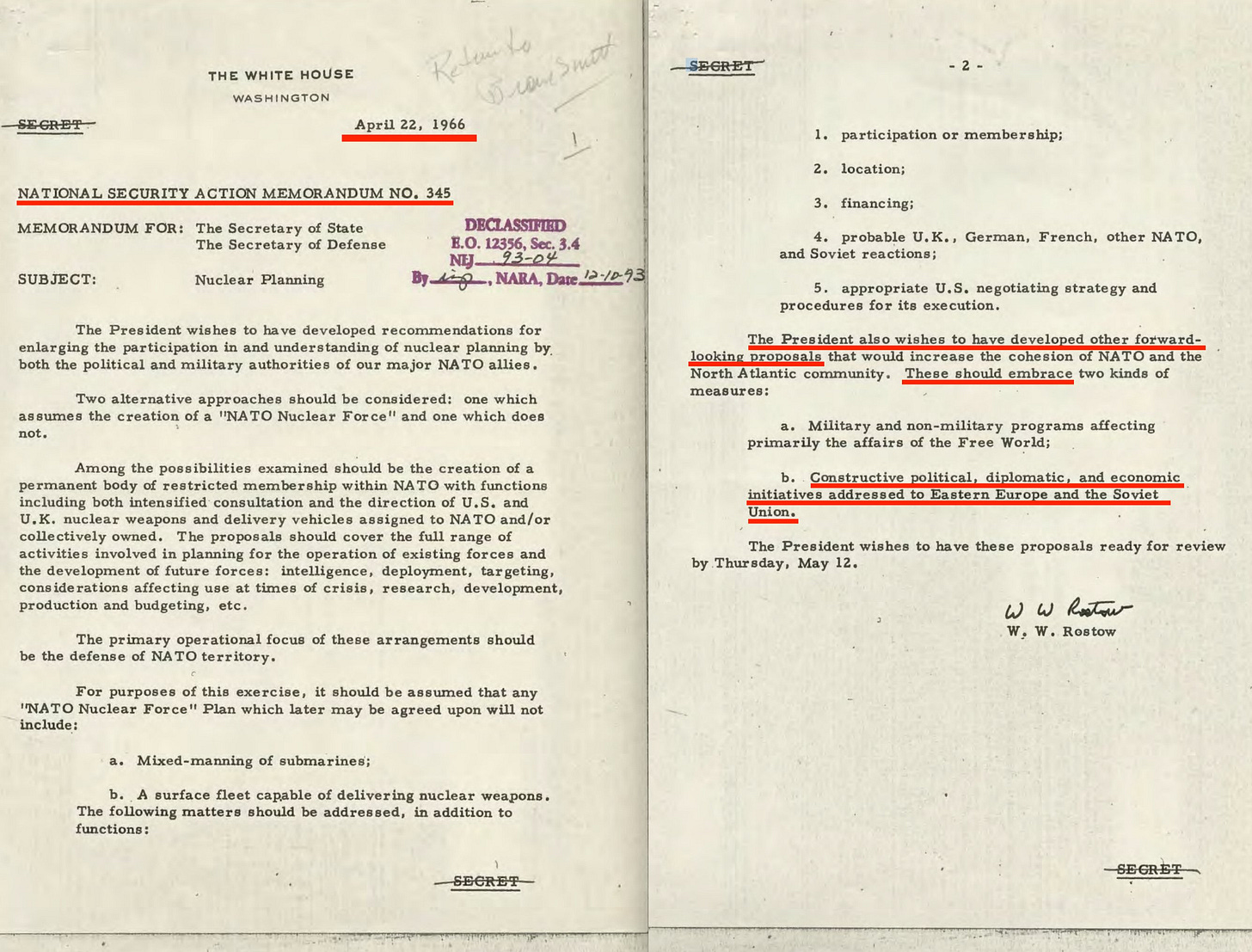

Then came NSAM 3453, issued in the heart of the Cold War:

The President also wishes to have developed other forward-looking proposals... These should embrace... Constructive political, diplomatic, and economic initiatives addressed to Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union.

It was an extraordinary development—and it raised a few rather pointed questions.

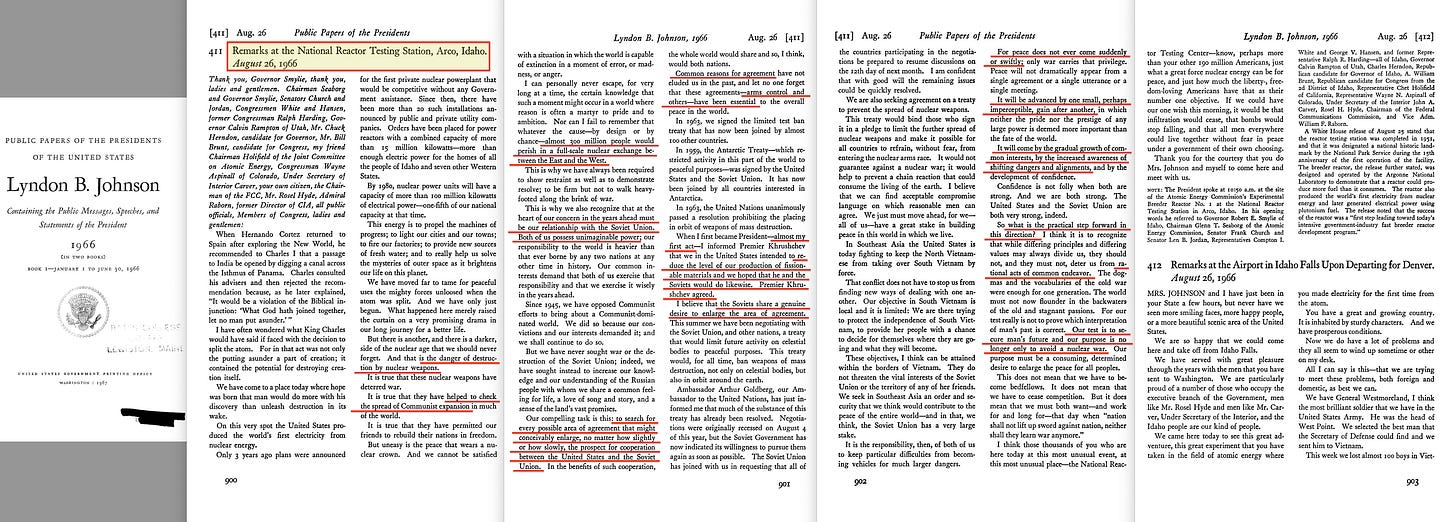

By August, 19664, Johnson delivered remarks at a nuclear testing station which, while couched in the context of nuclear diplomacy, expanded the vision considerably:

Our compelling task is this: to search for every possible area of agreement that might conceivably enlarge, no matter how slightly or how slowly, the prospect for cooperation between the United States and the Soviet Union.

This culminated in Nixon’s signature on the historic May 23, 1972 US–USSR Agreement on Environmental Protection. But the conceptual groundwork had already been laid—and Johnson's speech reveals the deeper strategic logic:

For peace does not ever come suddenly or swifdy; only war carries that privilege. Peace will not dramatically appear from a single agreement or a single utterance or a single meeting.

It will be advanced by one small, perhaps imperceptible, gain after another, in which neither the pride nor the prestige of any large power is deemed more important than the fate of the world.

It will come by the gradual growth of common interests, by the increased awareness of shifting dangers and alignments, and by the development of confidence.

Confidence is not folly when both are strong. And we are both strong. The United States and the Soviet Union are both very strong, indeed.

So what is the practical step forward in this direction? I think it is to recognize that while differing principles and differing values may always divide us, they should not, and they must not, deter us from rational acts of common endeavor. The dogmas and the vocabularies of the cold war were enough for one generation. The world must not now flounder in the backwaters of the old and stagnant passions. For our test really is not to prove which interpretation of man's past is correct. Our test is to secure man's future and our purpose is no longer only to avoid a nuclear war. Our purpose must be a consuming, determined desire to enlarge the peace for all peoples

Peace—the supposed ultimate objective of the United Nations, and the League of Nations before it—was to be pursued not through deterrence or ideology, but through rational, common purpose. A peace built not on the absence of war, but on the gradual cultivation of shared interests, guided by a growing awareness of shifting global dangers.

In light of the rise of environmentalism—and Gorbachev’s 1987 speech—it feels oddly prophetic, doesn’t it?

Later that same year, in October, Johnson delivered further remarks—this time addressing the East–West divide in the context of Germany. There, he called for the establishment of a common East–West framework of cooperation, grounded in the ‘common good’. His vision included the expansion of Woolf’s neoliberal trade policies, the creation of a ‘peaceful and just world order’, sustained ‘peaceful engagement’ between the blocs, and the cultivation of healthier economic and cultural ties with the Soviet Union.

He even divulged that the United States and the Soviet Union had begun exchanging satellite imagery — specifically from weather satellites of the kind first proposed in the early 1960s… around the same time the CIA launched its CORONA reconnaissance programme.

On trade, he proposed that East and West should collaborate through a neutral third-party institution—the OECD—in order to pursue mutual interests and, ostensibly, to advance the common good. All of this, we are told, was to facilitate far-reaching improvements in East–West relations.

Now, of course, I understand. This wasn’t an outright admission. It could all be entirely innocent. But the timing is… interesting — especially given the geopolitical atmosphere just a few years earlier, in the wake of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

But don’t just take my word for it. You can read it directly on IIASA’s own website5, the institute founded in the wake of the May 23, 1972 U.S.–USSR Agreement on Environmental Cooperation. A rather aggressive development, all things considered.

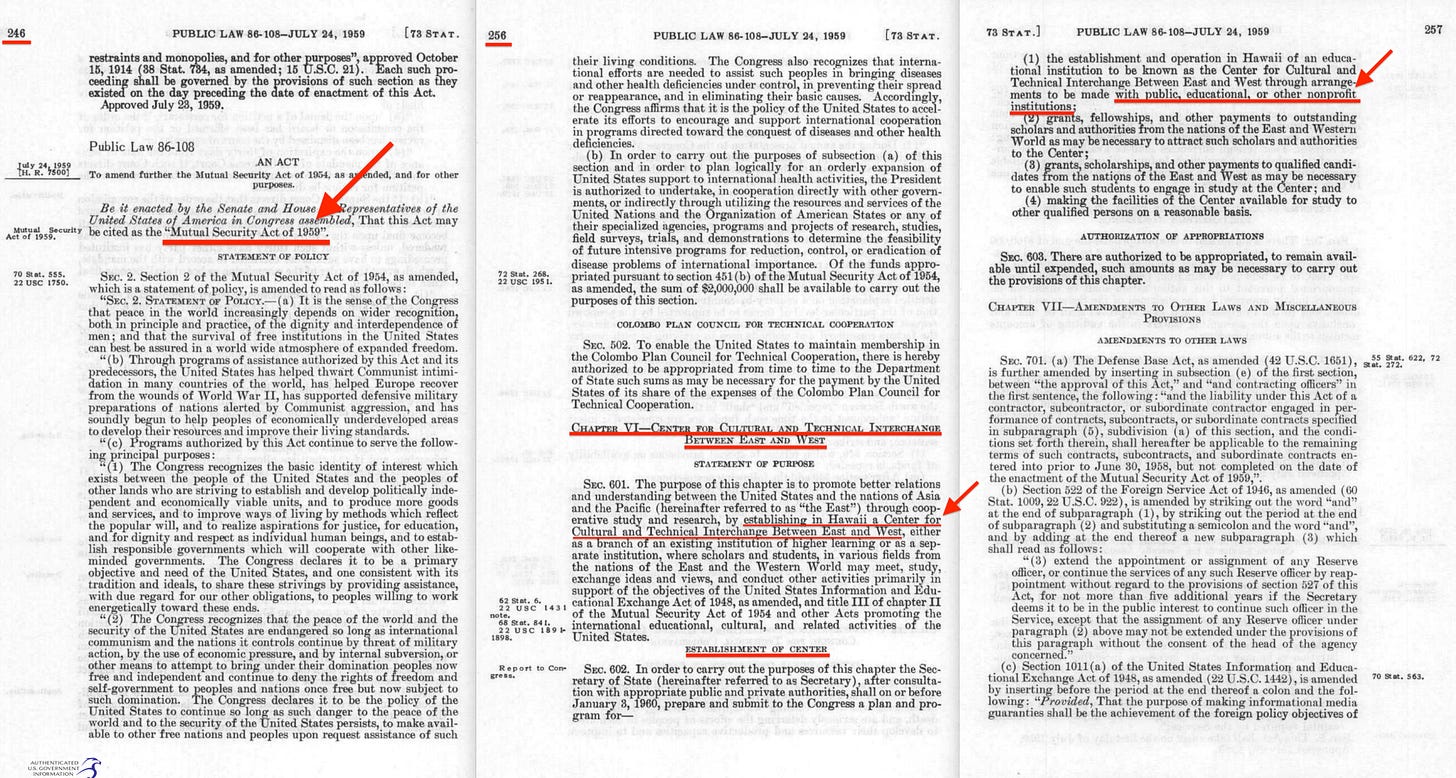

What’s also worth noting here is that Lyndon B. Johnson was a co-sponsor6 of the Mutual Security Act of 19597 — legislation that called for the creation of the East–West Center in Honolulu, a hub designed to foster cooperation between the blocs. And, as one might expect, it explicitly involved NGOs from the outset.

I’ll admit, for a while I couldn’t quite work out how the East–West Center fit into the broader picture. At first glance, their material just seems so... random. A scattered collection of academic themes, cultural exchange, policy dialogues. Nothing that clearly pointed to a strategic function.

But as with all of this, it comes down to pattern recognition. And this particular pattern took a while to reveal itself. It wasn’t until I examined how the Soviet Union structured its advanced training programmes for agents—particularly those involved in long-term influence operations—that the pieces finally began to fall into place.

The East–West Center wasn’t focused on any one subject. It wasn’t about the content—it was about the structure. The architecture. The connective tissue between disciplines. Its purpose was to explore how seemingly unrelated domains could be systematically organised, harmonised, and synthesised—within the constraints of East–West cooperation. And the framework that made that possible?

General Systems Theory.

The Society for the Advancement of General Systems Theory was founded only a few years earlier—unsurprisingly, with backing from both the AAAS and the Rockefeller apparatus. Its first president was Kenneth Boulding, who, in 1966, published his influential paper The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth8.

In it, Boulding framed ‘Spaceship Earth’ as a closed-system model of the planet—a finite, self-contained system subject to measurable inputs and outputs. And once you frame Earth in those terms, the rest follows logically. A closed system can be modelled. It can be subjected to Input–Output Analysis. It can be monitored through global surveillance networks tracking the flow of carbon, resources, and capital.

With General Systems Theory as the scaffold, and digital twins as the operational interface, you can simulate the planetary system—run scenarios, predict feedback loops, and identify control points. This is the logic of forward prediction. And once you can predict the system’s responses, you can manage them.

That, essentially, is cybernetics: the conscious manipulation of system feedback. Implement automatic adjustments in real time based on projected feedback, and what you have is active adaptive management—the cornerstone of technocratic control.

Incidentally, you might recognise Input–Output Analysis by its more contemporary branding: the circular economy9. Its biological cousin—concerned with tracking flows not just of resources, but of all forms of life—is now known as circular health10. Though you’re likely more familiar with its alternate and more marketable label: One Health11.

This model also aligns closely with what’s known as the Ecosystem Approach—a top-down framework for integrated landscape management. First introduced into the UN agenda at the 1976 Habitat Conference, it effectively called for the gradual phasing out of private land ownership. That call was later echoed and reinforced in the 1982 World Charter for Nature.

As for systems theory frameworks you may already be familiar with, we can add Planetary Health and the Total Human Ecosystem—the latter having already been briefly discussed above. Each of these, in their own way, extends the same logic: the management of the human species within a closed, monitored, and cybernetically regulated planetary system.

And the East–West Center, more broadly, focused on the social science dimensions of this fusion. It wasn’t just about environmental or economic modelling; it was about cultural integration, behavioural conditioning, and institutional harmonisation. In essence, it explored how human systems—values, norms, governance—could be synthesised under a unified, cybernetic framework.

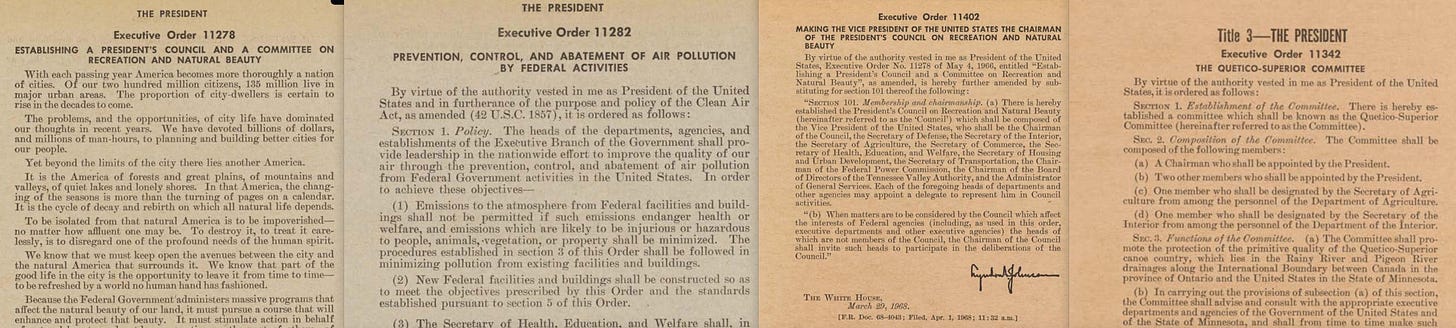

But circling back to LBJ—something curious happened. He suddenly began pushing through a flurry of legislation, including:

Clean Air Act of 196312: Debated during JFK’s presidency, but signed into law by Johnson in December 1963. It would become the foundation for an expanding regulatory regime.

Wilderness Act of 196413: Established the National Wilderness Preservation System, marking a new phase of federal land management.

Land and Water Conservation Act of 196514: Created the LWCF to fund conservation and recreational land acquisitions—again, expanding federal reach.

Comprehensive Health Planning and Public Health Services Amendments of 1966 15: An early push that ultimately led to the 1974 call for centralised healthcare planning in the United States.

Air Quality Act of 196716: One of the first federal attempts to address air pollution—laying the groundwork for far more comprehensive environmental controls down the line.

At the same time, Johnson began issuing a wave of executive orders—many of them aligned with this broader environmental and public health agenda. And that’s what makes it all so peculiar. This level of focus on environmentalism emerged well before any supposedly ‘settled science’ existed on the matter at all.

But as the Vietnam War escalated at the outset of Johnson’s second term, a different kind of executive order began to emerge—this time centred around finance. And interestingly, the beneficiaries all seemed to point in a single direction: the Federal Reserve. Under the guise of national interest, these orders facilitated expanded access to financial data—particularly from the large commercial banks—granting the Fed unprecedented visibility into the flow of capital, credit, and economic behaviour.

Information that would prove invaluable for refining input–output analysis models—precisely the type of economic modelling first formalised by Wassily Leontief in 1941.

And it was precisely information of this nature that was described in detail—particularly in the context of the 1973 oil supply shock—in the now-infamous document Silent Weapons for Quiet Wars. Dismissed by many as a conspiracy hoax, it nonetheless offered an uncannily accurate depiction of the technocratic logic at play: a world governed not by open force, but by systems management, economic modelling, and social engineering.

Through deeply subversive means, it effectively advertised Keynesian economics as the vehicle of transformation—one that would, slowly and imperceptibly, transfer power away from governments and toward the central banks.

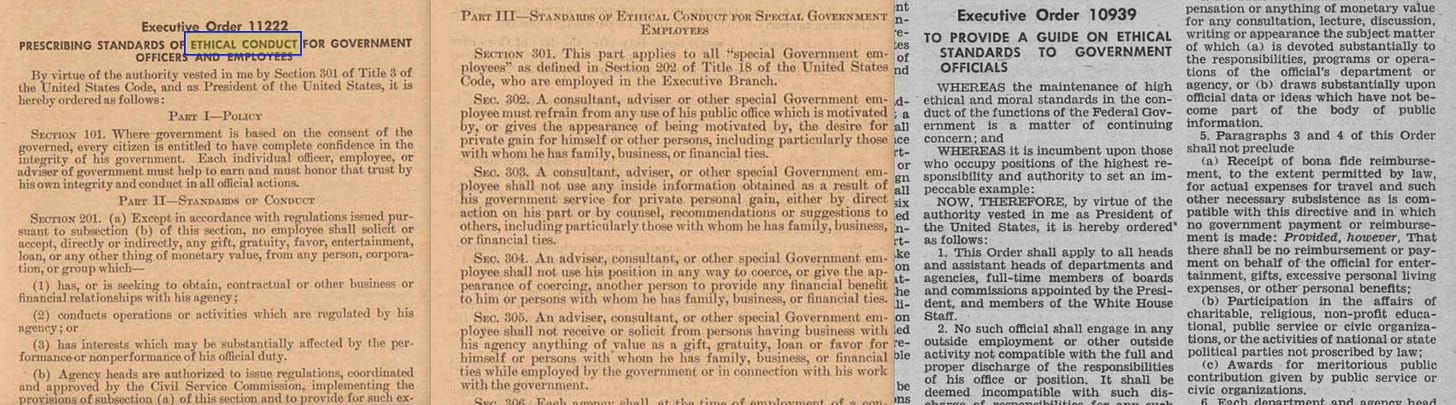

But—perhaps more notably—LBJ also signed an executive order mandating a significant expansion of ‘ethics codes’ for federal employees. What began as a bureaucratic measure soon laid the groundwork for something far larger. Over time, this initiative expanded to encompass the vast majority of those working in scientific and technical fields—particularly through the efforts of ICSU’s SCRES, established in 1996, and UNESCO’s COMEST, founded the following year in 1997.

And what ethics effectively does—clearly demonstrated during the COVID-19 crisis through the dismissal of healthcare professionals for alleged ‘ethics violations’—is compel obedience. It becomes, in practice, a directive masquerading as virtue. In times of so-called crisis, it does not guide behaviour—it mandates it.

Meanwhile, in 1965, the White House Conference on International Cooperation was convened. Its stated goals were strikingly familiar: the establishment of a new order of world cooperation, the development and conservation of global resources, coordinated methods to eliminate destructive disease, and—of course—the pursuit of world peace. A course of action which, intriguingly, appears to align rather precisely with executive orders that—at the time—had not yet even been signed.

And while this was unfolding, Harold Coolidge and Russell E. Train were quietly co-authoring a draft proposal for what would later become UNESCO’s World Heritage Trust17—a mechanism designed for the global conservation of landscapes under supranational oversight.

Incidentally, Coolidge was serving as president of the IUCN at the time18, while Train—perhaps more crucially—would go on to draft the very same May 23, 1972 U.S.–USSR Agreement on Environmental Cooperation repeatedly referenced above.

Consequently, when the 1968 UNESCO Biosphere Conference was formally proposed at the 1966 UNESCO General Assembly19, the major cornerstones that would later be enshrined in its 20 recommendations were already well in motion. The groundwork had been laid—quietly, incrementally, and with strategic precision.

That momentum would soon culminate in the fateful signature on the dotted line by Richard Nixon in 1972, marking the formalisation of a new era: environmental cooperation as a geopolitical instrument.

And SCOPE, of course, was the body that drafted the reports which directly led to the creation of UNEP’s Global Environmental Monitoring System (GEMS). At the heart of it sat Victor Kovda—a senior figure whose deep alignment with Moscow was never seriously questioned.

Meanwhile, on 17 September 1969, U.S. diplomat Daniel Patrick Moynihan issued a bold call for NATO to establish global environmental surveillance—an initiative that soon materialised as the NATO Committee on the Challenges of Modern Society (CCMS). Yet Moynihan was swiftly replaced by none other than Russell E. Train.

There’s simply no way Moscow wouldn’t have been aware of Train’s dual role—not only as the lead U.S. negotiator on the May 23, 1972 environmental cooperation agreement with the Soviet Union, but also as the newly installed head of NATO’s environmental surveillance programme.

And yet… the Soviets didn’t back out. Which leads to only one reasonable conclusion: by that point, Moscow was already fully aligned with the agenda.

Consequently, it is entirely reasonable to conclude that agreement had been reached between the superpowers well before 1972. In fact, Johnson’s legislative and executive behaviour suggests that alignment occurred considerably earlier.

And it’s in that context I previously posed the question: what exactly did David Rockefeller discuss when he travelled to Moscow in 1964?

And though the science was far from ‘settled’, that didn’t stop the ideological machinery from moving forward. UNESCO’s Belgrade Charter20 of 1975 openly called for the integration of environmental education into all levels of schooling—not merely as curriculum content, but as a transformative process aimed at reshaping values, attitudes, and behaviour. Crucially, it advocated the expansion of this effort through the cultivation of a global ethic.

That same year, the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) released the very first paper on carbon pricing. And yet, in 1976, Bert Bolin—later head of the IPCC—testified before the U.S. Congress and openly admitted that they knew very little, if anything at all.

Temperature patterns at the time were erratic and unpredictable. But then—rather curiously—following the implied carbon consensus of 1979 at the first World Climate Conference, global temperatures began to rise… almost in a straight line. A strange development, especially given that an IIASA workshop held just prior had concluded that scientists knew virtually nothing about the oceanic carbon cycle—by far the largest and least understood component of the entire carbon equation.

In other words, it was policy that consistently led the so-called science—not the other way around. Even Moiseev, by the late 1970s, openly acknowledged that predicting weather through global models was an impossibility. And yet, he persisted. Which leads to an unavoidable conclusion: the environmental narrative was never the end—it was the means.

Environmentalism was the pretext. The mechanism was the goal.

Global governance—justified on the grounds of planetary stewardship—implemented through leading NGOs, aligned with supranational institutions, and insulated from democratic accountability.

But let’s return to the Soviet Union.

In 2024, the All-Russian Society for the Protection of Nature—commonly known as VOOP—celebrated its centennial. On the occasion, even Vladimir Putin21 sent official greetings to the organisation, commending its:

… much-needed initiatives that contribute significantly to the preservation of our reserve areas, unique water resources, and biodiversity of ecosystems

But things were not always easy for the organisation, otherwise known as VOOP.

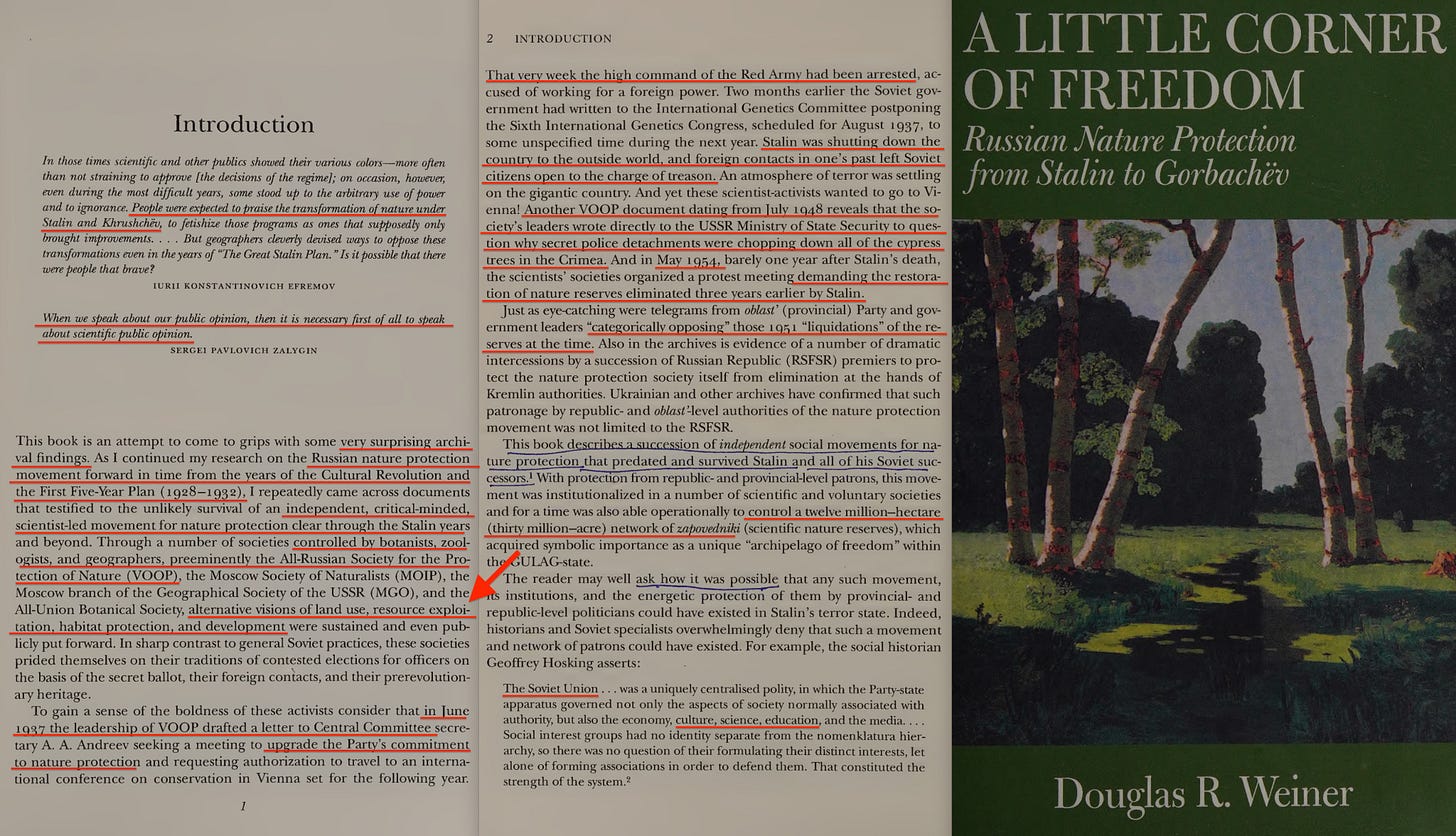

In 1999, Douglas Weiner published A Little Corner of Freedom22, a groundbreaking study of Soviet environmentalism. In its introduction, he reveals:

This book is an attempt to come to grips with some very surprising archival findings. As I continued my research on the Russian nature protection movement forward in time from the years of the Cultural Revolution and the First Five-Year Plan (1928-1932), I repeatedly came across documents that testified to the unlikely survival of an independent, critical-minded, scientist-led movement for nature protection clear through the Stalin years and beyond. Through a number of societies controlled by botanists, zoologists, and geographers, preeminently the All-Russian Society for the Protection of Nature (VOOP), the Moscow Society of Naturalists (MOIP), the Moscow branch of the Geographical Society of the USSR (MGO), and the All-Union Botanical Society, alternative visions of land use, resource exploitation, habitat protection, and development were sustained and even publicly put forward.

VOOP, in short, began articulating its vision for nature protection around the same time that the British Marxists—those who would later organise the 1941 Science and World Order conference—were making regular pilgrimages to Moscow. And only a few years later:

To gain a sense of the boldness of these activists consider that in June 1937 the leadership of VOOP drafted a letter to Central Committee secretary A. A. Andreev seeking a meeting to upgrade the Party's commitment to nature protection and requesting authorization to travel to an international conference on conservation in Vienna set for the following year.

That very week the high command of the Red Army had been arrested, accused of working for a foreign power. Two months earlier the Soviet government had written to the International Genetics Committee postponing the Sixth International Genetics Congress, scheduled for August 1937, to some unspecified time during the next year. Stalin was shutting down the country to the outside world, and foreign contacts in one's past left Soviet citizens open to the charge of treason.

VOOP, essentially, continued to speak out during a period when few dared to. This was the post-1936 Constitutional Reform era—an ostensibly liberalising move that, as Hannah Arendt later observed, directly preceded what she termed a gigantic super-purge. In its wake, the Soviet state undertook a systematic campaign to eliminate dissent—not only political, but scientific, intellectual, and institutional.

Yet even that didn’t deter VOOP.

Another VOOP document dating from July 1948 reveals that the society's leaders wrote directly to the USSR Ministry of State Security to question why secret police detachments were chopping down all of the cypress trees in the Crimea. And in May 1954, barely one year after Stalin's death, the scientists' societies organized a protest meeting demanding the restoration of nature reserves eliminated three years earlier by Stalin.

Just as eye-catching were telegrams from oblast' (provincial) Party and government leaders "categorically opposing" those 1951 "liquidations" of the reserves at the time.

Incredibly, the members of VOOP seemed utterly undeterred by the threat of gulags, denunciations, or worse. At a time when almost all civil society organisations had been dismantled, VOOP continued to act—not just to survive, but to resist.

And though Douglas does not provide the answers, he does ask the correct questions:

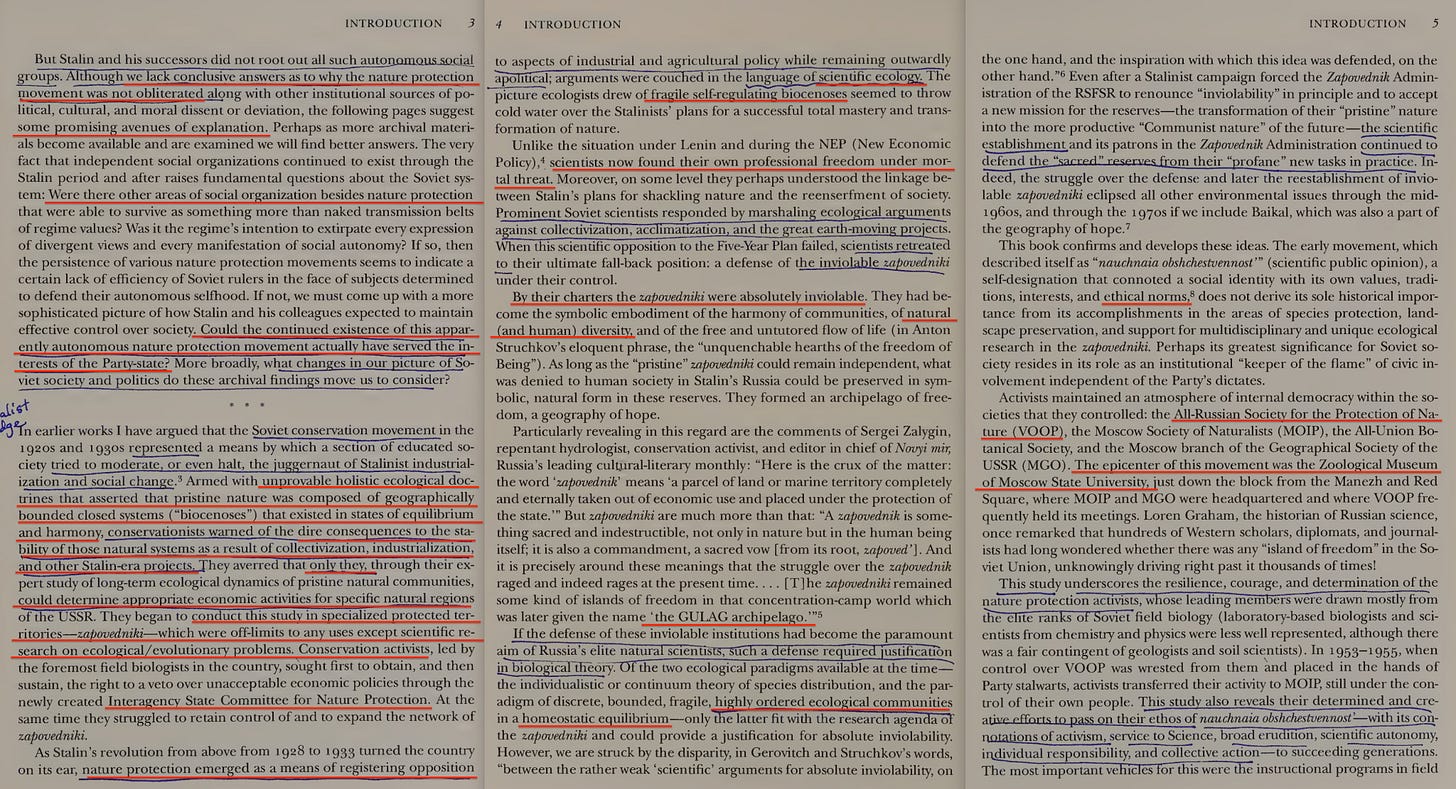

But Stalin and his successors did not root out all such autonomous social groups. Although we lack conclusive answers as to why the nature protection movement was not obliterated along with other institutional sources of political, cultural, and moral dissent or deviation, the following pages suggest some promising avenues of explanation.

Could the continued existence of this apparently autonomous nature protection movement actually have served the interests of the Party-state?

And that’s an interesting question, but assuming the question is yes — which objective might it have served?

VOOP became a member of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in 196023—a seemingly modest development, but one that took place at a highly charged moment. By then, Khrushchev’s reforms had largely stalled. Yet 1960 also marked, according to Anatoliy Golitsyn24, the internal planning phase for a Leninist New Economic Policy–based strategy—a global coup d’état by deception.

Suddenly, the Khrushchev years leading up to 1960 take on a new kind of weight. And it is within this strategic liminal space that we encounter Douglas Weiner’s 1993 paper, Three Men in a Boat: The All-Russian Society for the Protection of Nature (VOOP) in the Early 1960s25.

The paper documents a crucial turning point: in 1955, Khrushchev effectively eliminated VOOP’s institutional independence. What had once been a relatively autonomous, scientist-led civil society organisation was now being folded into the machinery of the Party-state.

By 1957, the consequences were already visible. One of VOOP’s longtime activists, Lakoshchenko, was expelled from the organisation after publicly criticising the new leadership for engaging in abuse of power and outright corruption.

The paper, in short, documents a series of corruption scandals that unfolded after VOOP's state-directed restructuring. In one particularly telling case, the ouster of the VOOP president was triggered not by official channels, but through public embarrassment—after his misconduct was exposed in a comedy magazine.

And yet, this raises a deeper question: why was any of this even allowed published?

… how the entire civil degradation of Bochkarev could have occurred in the first place. First of all, this episode happened during a time of political transition. Khrushchev had been removed in mid-October 1964 and all expectations…

It’s curious timing. Sure, it’s plausible that this period of political limbo created enough confusion for such behaviour to flourish unchecked. But what’s more intriguing is what followed:

… this band of elite biologists and their followers in educated society and the student population came to an important realization: that they were almost unique in representing a truly autonomoris, cohesive, self-actualized movement of a portion of the citizenry in opposition to central economic policies pursued by the regime.

They were, in essence, granted the rare privilege to speak out—alone among civil organisations—against core regime policies. An extraordinary coincidence, to be sure.

But what’s also revealed—between the lines—is something far more revealing than just the re-centralisation of VOOP. Weiner notes:

From the state-dictated removal of elected officers of VOOP in 1955 to Khrushchev's anti-intellectual and ill-considered "second liquidation." of zapovedniki in 1961 (justified by an unanticipated attack on "useless field biology"!…

In other words, Khrushchev—like Moiseev in the 1970s—didn’t particularly care about the environment itself at all.

Clearly, the motivation lay elsewhere.

And there are interesting parallels here, because under Gorbachev, the same pattern repeated26.

Slivyak was not alone in his optimism. Ideas of perestroika and glasnost – the new policies of “restructuring” and “openness” ushered in by President Mikhail Gorbachev from 1985 – had breathed new life to Soviet civil society away from the suffocating confines of the state.

And in what aspects were these new freedoms applied, you ask?

Across the Soviet Union, people embraced this pocket of relative freedom to campaign for the world around them. Environmental activism exposed the greed and incompetence of a party apparatus willing to turn a blind eye to pollution and cover up the failures of the Chornobyl disaster. But it also allowed people to take ownership of their lives and communities, striking blow after blow against the authoritarian state.

And what did that, eventually, facilitate?

“I think the environmental movement contributed much more than other groups to dismantling that system,” says Slivyak “We were promoting democracy with direct action. We didn’t ask the government for permission: we went into the street and did what we needed to do.”

Activism as democracy. Mob justice. The very same model endorsed by Tony Blair in The Third Way, published by the Fabian Society in 1998.

Carried out, of course, by Civil Society Organisations. And incidentally, upon the collapse of the Soviet Union, Gorbachev co-founded precisely one of those—Green Cross International27.

In 1979, Boris Komarov published The Destruction of Nature in the Soviet Union28, which detailed a mounting ecological catastrophe centred on Lake Baikal. Two massive pulp and paper combines, constructed on the lake’s shores in 1963, had turned into environmental disasters. Gosplan—the State Planning Committee—didn’t care. Inquiries went unanswered. And when, after years of stonewalling, a special resolution finally granted a handful of senior scientists access to the project documentation, they uncovered what amounted to an institutionalised lie: exaggerated claims about the ecological benefits of the operation.

Later that same year, a special commission was convened to investigate. Its findings? The combines were perfectly acceptable from an ecological standpoint. It was a whitewash—thorough, cynical, and indifferent to the growing protests erupting across the country.

It would later emerge that the cover-up had been systematised through a series of resolutions—starting with a 1963 directive issued by none other than Khrushchev himself. Two more followed: one in the late 1960s, and a final clampdown in 1975. The last didn’t just restrict access to the documents—it censored the mass media from disseminating any ecological information concerning the condition of Lake Baikal.

The book carries on by outlining the catastrophic state of the environment, citing plenty of examples while the party apparatus naturally lie about it.

As the ecological situation worsened at the beginning of the seventies, special circulars restricting the scope of information on pollution were issued at least two times.

Since 1975 you will not find a single reference to pollution of the air, the water, or the soil even in special articles.

And why is all of this so troubling?

Because the United States engaged with the Soviet Union in environmental cooperation with that signature by Nixon in 1972. An agreement, which rapidly expanded into every other sphere of the environment.

Yet, the Soviet Union didn’t care. Even if the United States were not fully aware — which is a possibility, however remote — they for sure would have picked up on the complete lack of data relating to pollution numbers, or rather, that simple fact alone should have seen the United States pull out of the agreement immediately.

But it gets worse:

The public’s influence on the solution of ecological problems is becoming a very powerful factor. But as the Baikal story has shown, for us mass participation in solving such problems is practically impossible. One of the main reasons for this is the lack of objective information, the impossibility of comprehending the situation as a whole and its possible development

See, whether a Civil Society Organisation — controlled by the Communist Party or not — protests hardly matters if a suitable information clearinghouse has been created, expressly facilitating the control of information.

Yet, in spite thereof:

… many Europeans and Third World visitors believe that they are experts on successful environmental protection in Russia. Especially genetically predisposed to the wiles of showcases are such people as the French Marxist Guy Biolat or the Italian Communist Senator T. Budesto, who declared that only socialism and only the USSR could provide what was necessary for the preservation of nature

I could suitably mock both, but reality is that Europe was keenly aware of pollution issues in the Soviet Union in the 1970s. Information from defectors and insiders, rapidly expanding satellite imagery, and other monitoring efforts of international bodies meant that this was hardly much of a secret by then.

Yet:

The notorious resolution of the Council of Ministers of the USSR (No. 898, December 29,1972) on Intensifying the Preservation of Nature and Improving the Use of Natural Resources provided for making scientific forecasts of the state of the environment over the next twenty to thirty years.

The US–USSR Agreement was signed in May, 1972. By December, the Council passes a resolution aligning with… well, the title of the IUCN (and also a UN resolution). And they expected to make forecasts 20–30 years in advance, mere months after IIASA launched?

Such forecasts have been compiled by special commissions directed by such authoritative scholars as Academicians Gerasimov, Fedorenko, and the head of the Hydrometeorological Service, Corresponding Member of the Academy of Sciences Izrael.

… and cut.

You wouldn’t happen to know to whom this refers? No?

That would be Yuri29 Izrael30.

At the 8th Session of the IPCC (Harare, Zimbabwe, 11-13 November 1992), Professor Izrael was elected IPCC Vice-Chair, a position he held until 2008. In his 20 years of involvement with the IPCC as member of the Bureau, Professor Izrael was an advocate of scientific excellence

The vice-chair of the IPCC for sixteen years, and an alleged advocate of ‘scientific excellence’?

Well, in that case, please do answer me these questions:

Why did Izrael work to cover up continuous environmental disasters in the Soviet Union as head of the Hydrometeorological Service?

Why did the IPCC laud his patently false credentials?

Why did the West accept the Soviet Union’s continuous efforts relating to environmentalism, when they should have known of the looming disaster?

Why was Fedorov allowed, at the first World Climate Conference, to issue a call for the West to accept a societal ‘purpose’, a concept fundamentally alien to classical Western liberal democracy?

Why did UNESCO, through the Belgrade Charter, issue a demand for environmentalism to be integrated with education—when no legitimate science existed on the matter at the time?

Why did the Report of the North American Regional Seminar in 1976 carry forward this purpose, even to the extent of fusing information about alternate lifestyles into mainstream media programming?

Why did the IIASA publish a paper on pricing carbon before the underlying climate science had arrived—especially given Bert Bolin testified before Congress in 1976 that they knew very little, if anything at all?

Why did Moiseev continue his efforts in the late 1970s, despite concluding that forward-predicting climate was a fool’s errand?

Why did the United States not promptly reject the US–USSR Agreement on Environmental Cooperation, given they certainly would have had satellite information unveiling the true state of affairs by 1979?

Why didn’t the World Climate Conference in 1979 address the issue itself, but rather focused on planning the world of tomorrow on the assumption the science — yet to be established — was legit?

Why did Khrushchev fuse Party officials into VOOP in 1955—and if it wasn’t environmentalism that was to be Golitsyn’s Trojan horse, then what was?

Why did Brzezinski, in 1970, speak of finding a common purpose with the Soviet Union—one centred on ecology and the use of science?

Why did David Rockefeller go to Moscow in 1964?

Why was Viktor Kovda—who damn well knew about the issue of global surveillance raised by Moynihan and Train in 1969—further described as a “proficient propagandist of Party-politics and an internationally distinguished expert”, then elected as director of UNESCO’s Department of Exact and Natural Sciences following the International Geophysical Year of 1957—which included the Rockefeller-funded Keeling experiment?

And why was the 1972 Club of Rome report, Limits to Growth, repeatedly cited when not even GEMS existed — arguably, the first global environmental monitoring system on the planet?

There can really only be one realistic, credible explanation.

Because the environmental drive was never about the environment at all. It was about fusing the United States with the Soviet Union—under the banner of planetary stewardship, legitimised through IIASA’s computational modelling of global surveillance data. A project steered by democratically deficient NGOs, defining the global ‘common good’ to be implemented through the very same public–private partnerships that Marxist revisionist Eduard Bernstein proposed in 1899.

And following Nixon’s signature in May — and the founding of IIASA later that same year in 1972 — those NGOs required a forum, somewhere they could scheme in privacy against the people. And David Rockefeller carried the torch of Brzezinski’s call, founding the Trilateral Commission in 1973—an entity that continues to this day, where its members are offered an opportunity to strategise on how best to exploit the peoples of the world through Trisectoral Networks, first proposed by Wolfgang Reinicke in a report co-authored by several members of the Trilateral Commission itself.

Nevertheless, Boris Komarov—better known by his real name, Ze’ev Wolfson—released a follow-up work, The Geography of Survival, in which we quickly encounter familiar references: the Club of Rome, Paul Ehrlich, and the usual parade of alarmist claims… none of which ever came to pass.

And there are plenty of things to quote in this book, but there’s hardly a point. In Chapter 6, for instance, Wolfson outlines not only that Europe will be finished by 2030, but that the former Eastern Bloc is so polluted, you can tell the moment you cross the border. It even includes a section detailing ‘parameters’ that indicate possible future states of environmental collapse—not unlike the contemporary concept of Planetary Boundaries, one might suggest.

And what causes the collapse of Europe, according to him? Not just Soviet mismanagement—no, it’s the combined weight of both communist and capitalist environmental pollution. There’s your common purpose, right there.

And to that extent, the Soviet Union needs help—or else it’ll collapse backward into authoritarianism. Incidentally, expressly the same arguments made by Anatoliy Golitsyn in his 1995 book, The Perestroika Deception.

But we’ve all heard plenty of these alarmist predictions by now. Al Gore, for instance, manufactured an entire stream of environmental falsehoods in the late ’80s—conveniently summarised in one book, which at least makes it easier to dismiss wholesale.

So who was this so-called Boris Komarov? Well, that’s where things get murky.

According to a 2009 issue of Environmental Conservation31, published by Cambridge University Press, he allegedly worked on educational television programmes for the environmental and biological departments of the Soviet government.

Of course, as his own book makes perfectly clear, all environmental data in the USSR at the time was top secret. And yet, somehow, this supposed educational TV employee had access to a trove of unpublished documents—documents he admits were classified at the state security level by none other than Khrushchev himself.

Documents which, according to Eglė Rindzevičiūtė, not even the IIASA—the very flagship of East–West scientific collaboration—could reliably obtain.

We’re seriously meant to believe that someone working in Soviet television programming just happened to gain unrestricted access to sealed, high-security environmental archives?

.This story is, quite frankly, manufactured horse manure. His own book expressly contradicts his own explanation for how he obtained classified material. And yet—somehow—he was taken absolutely seriously32.

Here, for instance, is a glowing citation from The New Statesman’s 1981 special issue on Britain and the Bomb33:

If anyone still doubts the immense inertial interests of Soviet militarism, they should read Boris Jomarov's remarkable The Destruction of Nature in the Soviet Union*. with its fearsome sidelights: the poisoning of Lake Baikal by a factory making hardened cord for bomber wheels; the general disregard of ecological regulations by the defence industries; shoot-ups of wild life by high ranking military (helicopter hunting for polar bears, troop-carriers assaulting Black Sea wild-fowl).

Don’t worry about the spelling mistake. The Gruadian is infamous for just that.

But rather than relying on a handful of tabloid rags and their distorted propaganda, consider instead a declassified CIA report—released in 2010—titled Environmental Protection in the Soviet Union: More Smoke than Fire34, which begins by outlining that the little official statistics exist, that the Soviet Union allocate very few resources in that regard, consider it low priority, and focus on administrative measures as opposed to actually addressing the issue itself.

But it further lays out that until the late 60s, the Soviet Union couldn’t possibly have cared less about environmental disaster, but were forced to care by the early 1970s out of necessity.

The report is from 1985, and it provides examples of environmental disasters of the sort which would drive headlines in the West repeatedly, with an increased tendency of announcements of measures to combat the issue, but very little action. And while air pollution is a major problem, water pollution is probably even worse. But it is at this stage it takes a sharp turn:

A Soviet underground (samizdat) report by Boris Komarov suggests that the Soviet economy currently produces more pollutants per unit of output than the United States for any given activity.' While not offering any supporting documentation or detailed methodology, he asserts, for example, that the Soviet economy overall produces twice as many air pollut- ants per unit of output as that produced in the US economy

Great, the report links straight to Komarov. In fact, it even adds detail on who he is, and what he is presently up to:

Boris Komarov is a pseudonym of Vladmir Volfson, who from 1968 to 1978 was the senior lecturer with the Biological and Environmental Department of Educational TV in Moscow. The report was published in 1980 by Sharpe, White Plains, NY, under the title The Destruction of Nature in the Soviet Union. Mr. Volfson emigrated to Israel in 1981 and is a senior adviser in Israel's Environmental Protection Service, Ministry of the Interior.

Komarov — or should we call him Wolfson — was a lecturer, with supposed access to top secret information relating to the state of the environment, and he is now working as a senior advisor to Israel’s Ministry of the Interior. Well, so much for wiping off potential claims of him being a conspiracy nutcase.

But that’s not quite all:

Published commentary suggests that the major sources of air pollution are thermal power stations, the ferrous and nonferrous metallurgy industries, and the petrochemical industry. According to Yuriy Israel’, the Chief of the State Committee on Hydrometeorology and Environmental Protection (Goskomgidromet), damage from sulfur dioxide emissions is an especially critical problem. He reports that in the northern and northwestern parts of the USSR such emissions, falling in the form of acid rain, have caused great harm to the water, soil, and vegetation.

Well, that’s rather funny. It was Izrael who was tasked with producing forward-looking environmental predictions of precisely the kind that Moiseev had insisted could not be done. And twenty years on from the 1972 US–USSR agreement—which birthed IIASA, among other things—lands us in 1992, the year the IPCC promoted Izrael to vice-chair. His claims at the time focused specifically on sulphur dioxide, and therefore on acid rain—a topic which really deserves a chapter of its own. The alarmist forecasts issued by IIASA had prompted the creation of a model, and it was this model which later calculated the alleged environmental improvements that supposedly followed the West’s clean-up efforts.

But that’s not really the central issue. What Izrael was saying is that SO₂ emissions were affecting the northern and northwestern parts of the USSR and reaching all the way down to Ukraine. That is a vast expanse of territory—meaning the emissions must have been epic in scale, effectively blanketing the entire western portion of the Soviet Union. In fact, the spread must have been so severe and so extensive that it could not possibly have avoided spilling into Western Europe, especially considering that many of the USSR’s thermal power stations were located near major population centres—most of which were west of the Urals, in European Russia.

And why is that a problem? Because IIASA, at the very same time, was claiming that the regions most affected by acid rain were in Northern Scandinavia—an area that would almost certainly have been impacted by such a monumental plume of sulphur dioxide drifting westward out of the USSR.

Yuriy Izrael claimed that sulphur dioxide emissions from the northern and northwestern USSR were so widespread that their effects reached as far south as Ukraine, implying an atmospheric corridor of nearly 2,000 kilometres and a chronic SO₂ burden across the western Soviet landmass. Given prevailing westerly wind patterns, such emissions would not have remained confined to Soviet territory but would have spilled into Eastern and Central Europe, and very likely into Scandinavia as well. Yet at the same time, IIASA—a Vienna-based East–West systems modelling institute founded in 1972—advanced a narrative in which acid rain damage in Northern Scandinavia was primarily caused by Western industrial nations, particularly the UK and Germany. This positioned the West as the environmental villain and provided the rationale for supranational, model-driven regulation. But if Izrael’s claims were correct, then Soviet emissions would have been a major contributor to the very damage IIASA attributed solely to the West. The two narratives are mutually exclusive, suggesting that selective modelling was employed not to reveal the truth but to serve a particular geopolitical end.

In short:

If SO₂ dispersion was truly as vast as Izrael claimed, then IIASA’s Scandinavian acidification model must have been grossly underrepresenting Soviet contributions.

This protected Soviet diplomatic credibility during the Cold War, while advancing the supranational science-based regulation agenda — soft power via systems theory.

The acid rain chapter isn’t just a minor prelude to climate governance — it's a trial run in selective modeling, controlled forecasting, and narrative laundering through supranational ‘scientific’ consensus. It even served as the model upon which the 1992 Combating Global Warming suggested basing the future model of carbon emission monetisation. It even stretches back to Bert Bolin himself, who crafted related reports for the 1972 Stockholm conference which led to the United Nations Environmental Programme.

And setting even that aside — this epic blanket of so2 emissions could not possibly have come about in brief period of time, which makes any claims of him performing ‘scientific excellence’ by the IPCC stand out as absurd. He could have easily warned the international community, yet — per Komarov — these were considered state secrets. In fact, it’s only through a declassified CIA report this has even come up35.

What I am unequivocally stating — and that, without the shadow of a doubt — is that the environmental narrative is not just slightly flawed — it is outright, deliberate fraud. Fraud, perpetrated from the highest echelons of power. Fraud, which currently imposes vast taxation upon especially the populace of the West, while their elected politicians blatantly collude with environmental NGOs operating entirely outside of voter wishes, with complete and utter impunity. And this is presently taking place through the Trilateral Commission36, working to structure public-private-partnerships for the common good, where the ‘common good’ is never voted on, but the express output of opaque computational modelling which isn’t even allowed to be challenged.

It is not just fraud. It’s a global coup d’etat, executed in slow motion which led to the progressive fusing of the East and West through the illusion that the Soviet threat dissipated, and with environmentalism becoming a global, critical concern.

Exactly as Michael Gorbachev laid out in his speech in November, 1987.

So where should we go from here. Well, let’s return to the one of the primary characters of Discovery — Viktor Kovda. See, he participated in the early conversations leading to the 1972 Stockholm conference, in fact, he led the March 1970 delegation which also saw the participation of Yuri Izrael, and this particular report even include the mention of George M Van Dyne, who was among the very first to speak of the Ecosystem Approach, when essentially detail the application of General Systems Theory in the concept of top-down integrated landscape management. Ie, global control of land. As for Yuri Izrael, who promoted the global environmental monitoring on the Soviet side, he further wanted to split surveillance into two components — biotic (living), and abiotic (geophysical observations). But it’s otherwise mostly the same terrain in this article — with a few notable exceptions:

From the 10th to 20th of March, 1970, Soviet delegation headed by soil scientist Viktor Kovda (1904 – 1991) participated in the compilation of the program for the upcoming conference at the United Nations headquarters in New York City. Soviet delegation with the support of the delegations from France and Czechoslovakia promoted a conception of alarming destruction of the environment, which was connected with many social and economic reasons when capitalist countries and big corporations vastly exploited the nature of developing countries

The Soviet delegation — led by Viktor Kovda — went to the meeting, bringing fear of climate armageddon, at a time where not only no credible science even existed, but also at a time where the Soviet Union couldn’t possibly care less about environmentalism. And the next noteworthy inclusion arrives towards the end:

Laura A. Henry brings attention to environmental activism in the late Soviet period and according to her, such state-sponsored scientific organization as the All-Russian Society for Nature Protection (VOOP) and the Moscow Society of Naturalists (MOIP) were mostly the exception from the state industrial initiatives criticism [17].

We covered this previously, of course. However — we did not cover what comes next:

The Academy of Sciences of the USSR was a state-sponsored organization ranked much higher than VOOP and MOIP. From that point academic's institutions could be much more powerful and oppositional players in environmental initiatives. Scientists could be supported in their environmental initiatives for the purpose of abroad propaganda that the Soviet state is an environmental-friendly country

Because what that means is that VOOP, post-Khrushchev, was to be used as controlled opposition to lend credence to alleged claims of the Soviet Union caring about the environment.

In other words — kovda would go fearmonger about capitalist countries and their destruction of nature, and the controlled opposition, VOOP, would pretend all was well in the soviet union, and this could be weaponised internationally37.

Beyond that, a final look at the 1968 UNESCO Biosphere Reserve38 conference material, as Kovda… essentially outlines a point of view expressly aligned with systems theory (derived off Alexander Bogdanov’s Tektology), outlining ecosystems as discrete units of input-output systems (this Leontief’s analusis), before the report itself turns to the Spaceship Earth metaphor which in short should explain what this is all about.

Planetary Stewardship of Spaceship Earth, which is a closed-systems theory model of the entire planet.

And Izrael’s biotic monitoring can then be explained through Circular Health, with the Circular Economy relating to the abiotic.

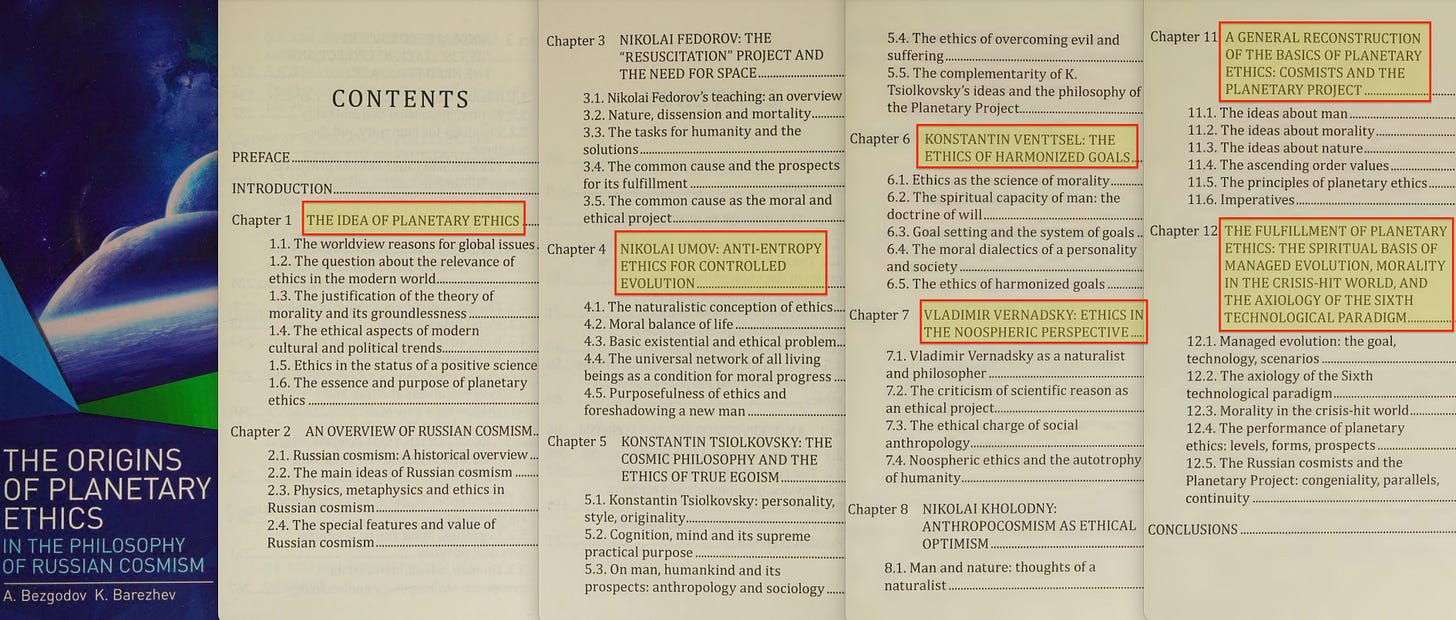

As for the origin of the 'Planetary Ethic'… it appears that, too, is Russian, per ‘The Origins of Planetary Ethics’ released in 201939. Also featuring the ethics of controlled evolution, the ethics of harmonised goals, the ethics of overcoming evil, and the ethics in the noosphere (Vernadsky).

So let’s wrap up. What does all of this actually mean?

It means that while no authoritative evidence exists (which would be deeply buried in a government archive if it even exists — beyond top secret), absolutely everything aligns with one explanation. An explanation which further synthesises two disparate timelines — that of global governance through Bernstein’s public–private partnership for the common good, and that of the global environmental movement driving the fusion of East and West. And these two timelines merge through the use of computational modelling carried out by NGOs for the sake of environmental governance.

It explains finance, through Julius Wolf, Eduard Bernstein, the Bank for International Settlements, RIIA, Keynes, Bretton Woods, Monetarism, MMT, and the Covid-19 era's outright monetisation of deficits everywhere.

It explains politics through Leonard S. Woolf, Alfred Zimmern, the League of Nations, the United Nations, the Third System, Perestroika, Agenda 21, and the Trisectoral Approach — all leading to the very same model, repeatedly. The very same employed by Lenin as he, in 1921, implemented the New Economic Policy: public–private partnerships for the common good, with that good defined by the Communist Party.

It explains environmentalism through the Soviet Union, the 1972 agreement, the carbon consensus, and its fusion into money with Combating Global Warming. It explains the Earth Summit, the role of the IUCN as our planetary stewards, and the IPCC’s role, cooking up falsehoods through computational modelling which are, essentially, nothing short of outright guesses — guesses which cannot even predict the emergence of hurricanes, as evidenced in 2023 and again in 2024.

It explains the comprehensive use of systems theory through Alexander Bogdanov, Wassily Leontief, Kenneth Boulding, C. West Churchman, General Systems Theory, Systems Analysis, and Adaptive Management through the computational modelling employed by the likes of the IPCC and the IIASA.

And it logically follows that Golitsyn was right. Perestroika was indeed a deception, driven through by nothing short of egregious fraud and corrupt science with no legitimate oversight — or possibility of appeal. And this outright fraud would gradually lead to a concentration of power in the hands of just a handful of increasingly powerful NGOs, alleged to operate for the common good.

Of course, in a similar vein to VOOP under Khrushchev… if those NGOs were controlled opposition, led by the Communist Party… then perhaps the difference between a common good defined by an environmental NGO and Lenin’s Communist Party suddenly disappears.

The reality is, that it does operate to someone’s good. Just not to 99.99% of us.

amazing work escape key. seriously amazing.

You were not kidding when you said “Deep Dive” I always put Golitsyn with the dodgy (to say the least) Bezmentov. I will have to reconsider.

BTW do you have a favorite Adam Curtis video?