‘All men have been created to carry forward an ever-advancing civilization’ —Bahá’u’lláh1.

Before we begin, I wish to make express that I do not blame or seek to scapegoat individual members of the Baha’i faith, just as I have not done with followers of other religions when addressing actions carried out by a handful of revisionists. Ergo, you will never find me blaming Christians, Muslims, Jews, Hindu, Baha’i, or Buddhists wholesale, though, over the past months, I have encountered members of every single one of those religions—but I have not and would never scapegoat the many because of the actions of a few. I am, however, more than willing to highlight individuals—and repeatedly have. However, not once was this due to their religious affiliation. Because the capacity to do both good and bad runs across every religion, every political ideology, every civic nationality, in fact, every strata of society. And to compound that difficulty, decisions are also commonly the outcome of circumstances.

The objective of these posts is not to scapegoat, but exclusively to identify power structures which seek to eliminate legitimate democratic principles, as this absolutely is taking place at present—especially when it comes to international diplomacy, accelerating within the United Nations ever since Maurice Strong Kofi Annan’s reforms. And, unfortunately, the Baha’i Faith stand out, mainly due to its organisational structure and (consultative) stakeholder decision-making process, coupled with an emphasis on exclusively divine revelation. Because this creates a structure where, ultimately, a quasi-supreme court equivalent will concentrate power with the few, creating a facility to control… everything, and all in the name of justice.

Especially if this should ever come to be implemented on a global scale.

Let’s begin with a very brief outline of the four pivotal messengers of the Baha’i Faith. The Báb2 outlined the purpose and acted as the forerunner of Bahá’u’lláh3, who was the prophet, divine educator and founder of the Bahá’í Faith. Then came ‘Abdu’l-Bahá4, who established the legal and administrative structure, and finally, Shoghi Effendi5 ensured the creation of the Universal House of Justice and gave life to the organisation. And if that appears to resonate with Erich Jantsch, with the purposive, normative, pragmatic and empirical outlined in order, here’s ChatGPT’s take6…

Either way—per the Baha’i Faith itself7:

All people are created to advance civilisation, as stated by Bahá’u’lláh.

Humanity has reached the threshold of its collective maturity, transitioning towards a planetary civilisation.

For centuries, followers of various religions have awaited the full revelation of divine guidance, which is now fulfilled by Bahá’u’lláh.

The essential first step for peace and progress is global unification, as peace and security depend on unity.

New social structures will emerge to reduce conflict, and global institutions will work to ensure equitable resource distribution.

Religion and science are complementary, guiding humanity’s intellectual and spiritual progress.

The overarching theme is that humanity is moving towards a unified, ethically governed planetary civilisation, with global institutions playing a key role in ensuring justice and stability.

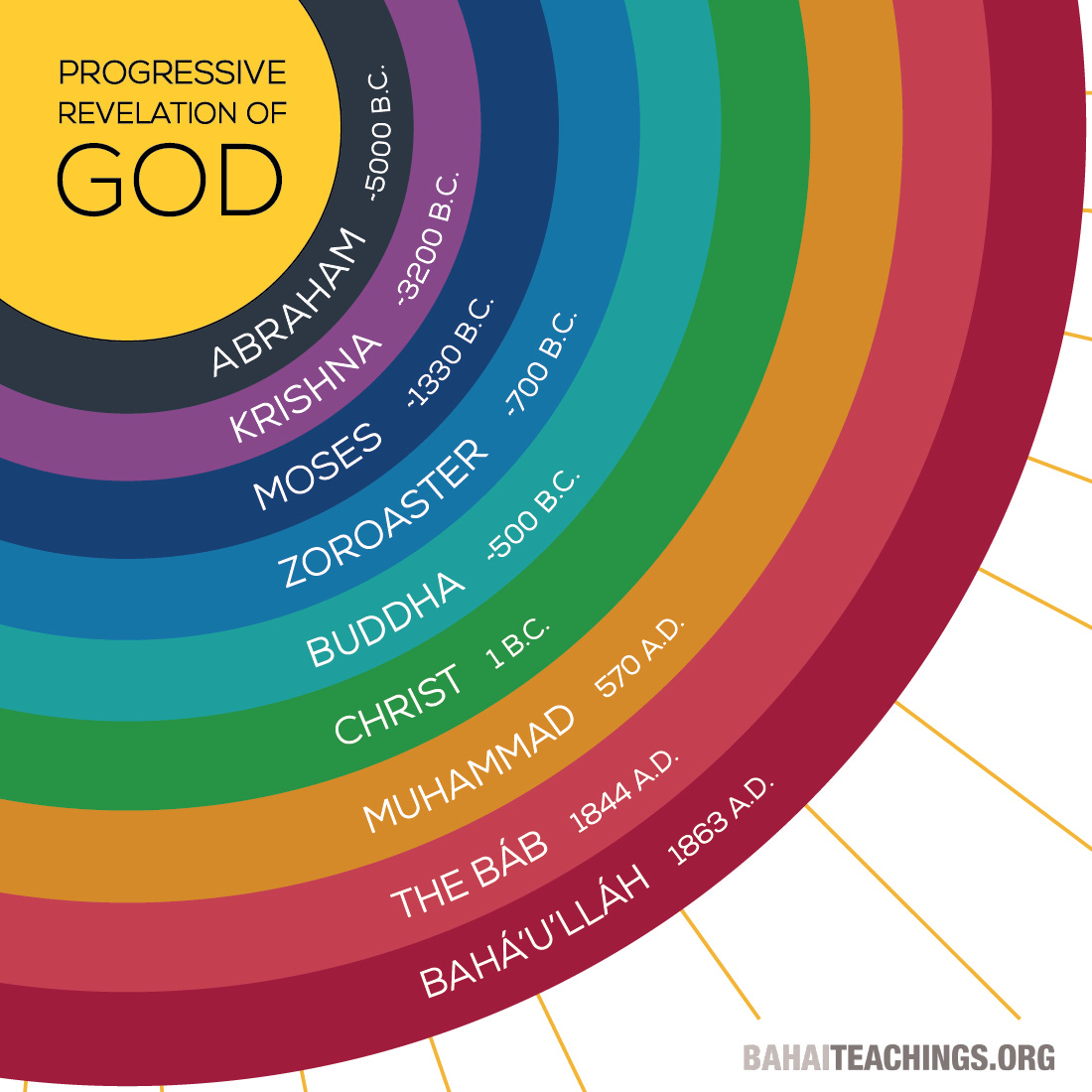

As discussed in part one, divine guidance has been progressively revealed through different prophets, each bringing teachings suited to the needs and capacity of their time. This process unfolds in a continuous and structured manner, with each revelation building upon the previous ones. Earlier teachings establish fundamental spiritual and moral principles, while later ones expand and refine them, through legislation guiding humanity towards greater unity and understanding.

This progression supposedly isn’t random but follows a deliberate pattern, ensuring that spirituality develops in harmony with human development. With time, these revelations address different aspects of being, considering both spiritual and societal needs, while maintaining a common theme of divine purpose.

The coming-of-age of humanity is a collective process, not merely individual8. The argument goes that the world’s current state of disorder suggests a transition towards a more unified stage of development. The unity of nations will emerge through suffering, as the disintegration of old systems eventually forces humanity towards a harmonious, unified order. Shoghi Effendi describes how modern Western civilisation’s struggles are interconnected with global challenges, outlining that Bahá’í teachings offer an alternative path to guide humanity through its crises. Ultimately—despite harsh trials for humanity ahead—these difficulties are seen as necessary steps towards achieving a single, just, and integrated world system.

Unity and the oneness of humanity act as foundations for achieving peace and disarmament, reflecting the Bahá’í vision of a world moving towards collective maturity9. The call for disarmament as essential for peace aligns with the idea that global security depends on a unified, cooperative framework, rather than fragmented national interests. The dissolution of national militaries in favour of a world federation suggests a transition from nation-state rivalries to a higher-order integration, where the needs of all humanity supersede individual national priorities.

And interestingly, this concept closely parallels Alexander Bogdanov’s vision of society as a human super-organism, where individual components function as part of an integrated whole. Just as biological systems require coordinated governance, a global society must be harmonised through ethical structures that guide both individual and collective behaviour, while an increasing global consciousness fosters cooperation, justice, and peace.

The economic interdependence of labour and capital is framed within this ethical progression. A world super-state with powers of taxation and economic coordination is called for, reinforcing neoliberal ideals of global trade and economic interconnectivity, first outlined by Leonard S. Woolf through ‘International Government’ as published by the Fabian Society in 1916.

But this further mirrors Tony Blair’s 1991 ‘Marxism Today’ article, which advocated a shift from traditional public vs. private sector disputes towards a public-private partnership for the common good—a structure where state power and corporate influence merge into an ethically guided system. And Blair emphasised the role of the Civil Society Organisation through his 1998 Fabian Society pamphlet, ‘The Third Way’.

Ultimately, this framework reinforces order as the guiding principle behind world integration. The Bahá’í teachings, as outlined in the article, present this evolution toward a harmonious world civilisation as both inevitable and necessary. The world federation, ethical control mechanisms, and integrated economic governance converge into a singular vision: a unified planetary order, justified through ethics, stability, and the pursuit of global justice.

The pandemic has acted as a catalyst for global transformation10, revealing an alleged fragility of existing systems while opening avenues for redefining collective values and reshaping governance. The United Nations—despite limitations—is positioned as the principal institution guiding this transition, serving as the platform for world leaders to forge a new global order. This order is framed around the common good, shifting governance from national sovereignty to global interdependence, where decisions must be assessed not for individual benefit, but for humanity as a whole.

At the core of this shift is a shared global ethic, which necessitates a major reordering of priorities. Traditional economic and political concerns must transition to align with planetary stewardship, ensuring sustainable management of biodiversity, climate, and resources. This realignment reflects earlier frameworks such as the IUCN’s Caring for the Earth (1991) and the Earth Charter (2000), both of which articulate a planetary ethic where human rights are tied to responsibilities toward the environment. This trajectory links back to the 1992 Earth Summit, which established climate and biodiversity as global priorities, and led to the establishment of the Convention on Bioligical Diversity, and the UNFCCC.

The role of world leaders in shaping this new paradigm cannot be understated. Their task is not merely to reform policies but to reconstruct governance itself, which includes proposals such as reforming the UN Security Council—particularly the veto system. Alongside state actors, global civil society is expected to play a fundamental role, aligning with Tony Blair’s vision of a public-private partnership for the common good—where governments, corporations, and civil society groups operate under an ethical framework to implement global governance goals.

This transformation is ultimately about constructing a new moral order, deeply tied to good governance—where ethical governance is not an abstract ideal but the core principle of a planetary civilisation. The transition toward a world order based on shared responsibility, equity, and environmental sustainability is not merely theoretical; it is actively unfolding through multilateral agreements, global governance mechanisms, and an emerging ethical framework that redefines peace, security, and human rights in planetary terms.

The world federation, the human super-organism, and the interdependence of labour and capital all serve as precursors to this evolving order. The ethical structures outlined in the Bahá’í writings, the economic shifts towards global trade governance, and the integration of environmental ethics into governance all converge into a singular trajectory: a unified planetary order, ethically justified and structurally reinforced. This represents the culmination of the ideas discussed—an evolution from disarmament, unity, and human oneness into a fully institutionalised global framework that governs through ethics, shared responsibility, and collective planetary stewardship.

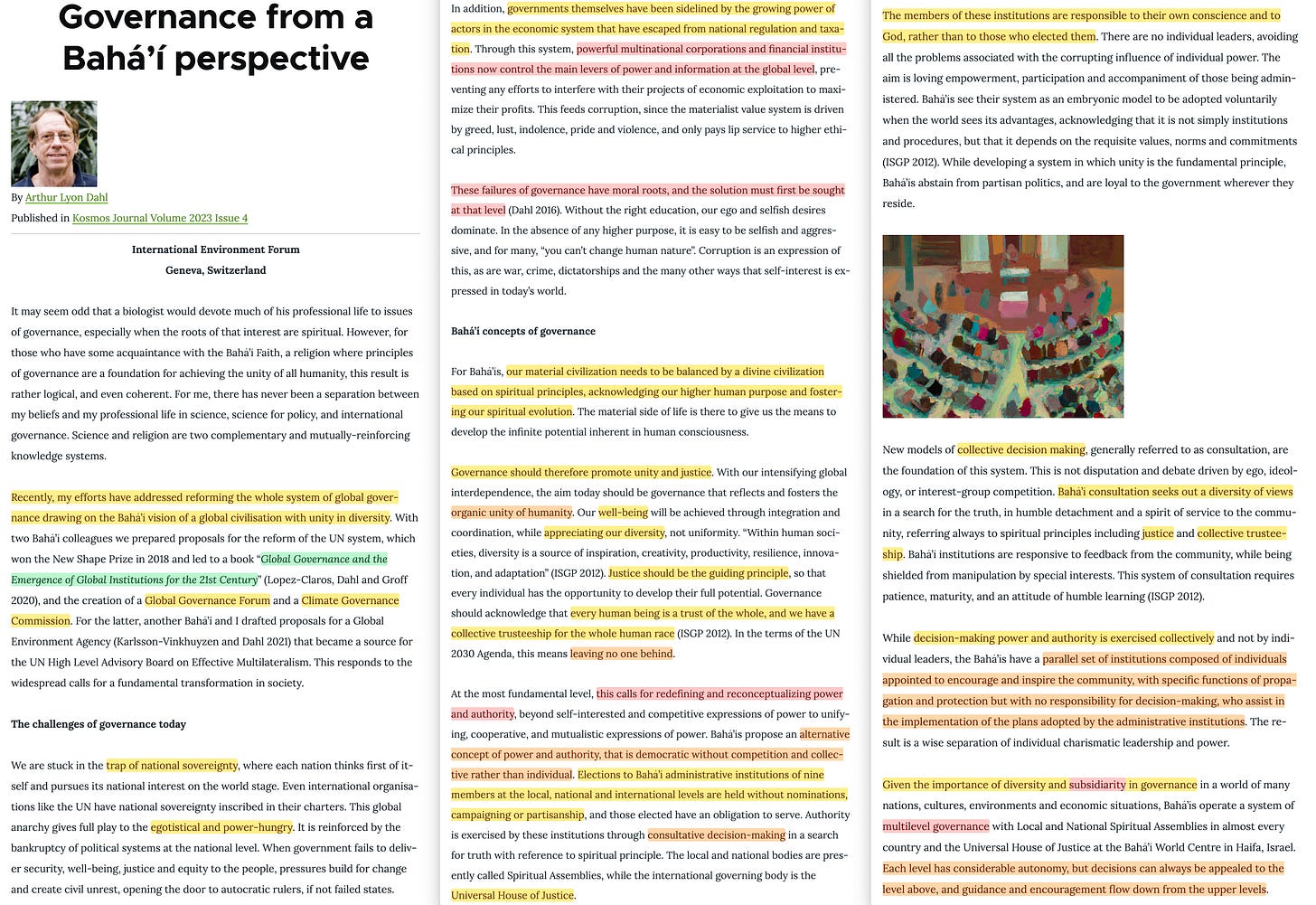

And useful to this extent is the International Environment Forum (IEF)11; a Bahá’í-inspired professional non-governmental organisation founded in 1997, that operates globally to address environmental sustainability and governance. With over 700 members across 90 countries on five continents, the IEF plays a role in integrating scientific and spiritual principles to ensure that modern technology is applied with wisdom and responsibility for all life, rather than being driven by materialistic or short-term interests. The organisation collaborates with major institutions, including the United Nations and the International Science Council (ISC), positioning itself within global efforts to shape sustainable policies.

At the heart of the IEF’s mission is the preservation of the ecological balance of the world, recognising that sustainability requires action at all levels, from local communities to global governance structures. This necessitates effective governance of the Earth system, ensuring that planetary management aligns with principles of moderation, reciprocity, and increasing global cooperation. Importantly, the IEF draws upon the ethical and spiritual principles of the Bahá’í Faith, integrating them with scientific knowledge to create a holistic approach to sustainability. This reflects a core Bahá’í teaching that science alone is insufficient to change human behaviour—true transformation requires an ethical and moral framework.

The recognition of the oneness of humankind and the unity in diversity are central to this approach, reinforcing that environmental and sustainable development issues must be addressed through a foundation of fundamental ethical and moral values. By bridging science and ethics, the IEF aligns with the broader Bahá’í vision of global stewardship, where environmental sustainability is part of a moral order that integrates governance, economic structures, and civic engagement into a cohesive planetary system. Through these efforts, the IEF exemplifies how Bahá’í principles translate into actionable governance models, linking ecological responsibility to broader global ethics.

And the International Environment Forum (IEF) is not just aligned with the Bahá’í Faith’s principles but serves as a direct application of its vision of governance, ethics, and planetary stewardship12. As highlighted in the Bahá’í-inspired framework for governance, the IEF operates as a science-based yet ethically guided organisation, integrating spiritual and moral principles into global environmental governance. This positions it firmly within the trajectory set by the IUCN’s Caring for the Earth (1991) and the Earth Charter (2000), both of which frame sustainability as an ethical imperative tied to human responsibilities, not just rights.

The IEF explicitly advocates for the preservation of the ecological balance of the world, insisting that environmental action must be grounded in governance structures that enforce planetary responsibility. It recognises that governance must balance scientific expertise with spiritual wisdom, ensuring that technological and economic development serve the common good rather than being driven by materialist motives. The call for the effective governance of the Earth system aligns directly with global initiatives for planetary management, reinforcing the Bahá’í emphasis on justice, sustainability, and unity.

A key feature of this governance model is subsidiarity—ensuring that governance functions at the most localised level possible while always maintaining the ability to be overridden from the top when necessary. This reinforces the hierarchical structure envisioned in global governance, where decisions can be adapted at the local level but must ultimately align with the overarching ethical framework established at higher levels of administration.

The Bahá’í perspective on governance suggests that material civilisation must be balanced by a divine civilisation, ensuring that governance structures do not solely operate on power, wealth, or economic interest but are guided by moral accountability. The book Global Governance and the Emergence of Global Institutions for the 21st Century provides a practical roadmap for how such a world federal system—with executive, legislative, and judicial functions—could facilitate collective security, equitable resource distribution, and environmental protection.

While the Bahá’í governance model promotes consultation, diversity, and a bottom-up approach in governance, it explicitly maintains that decisions must ultimately align with the moral framework set by higher governance structures. The IEF’s role in planetary stewardship is a clear extension of this, operating within the broader United Nations framework while adhering to a global ethical system.

As the world transitions toward a new governance structure, institutions like the IEF represent a bridge between ethics, sustainability, and governance. The shift toward planetary stewardship, embedded in both Bahá’í governance and global sustainability initiatives, reinforces that this new world order is not just about economic efficiency but about redefining governance itself through ethics. The IEF thus stands as an example of how Bahá’í principles are actively shaping global policy, ensuring that planetary management remains tied to a higher moral order—one that envisions a unified global civilisation governed by justice, cooperation, and shared responsibility.

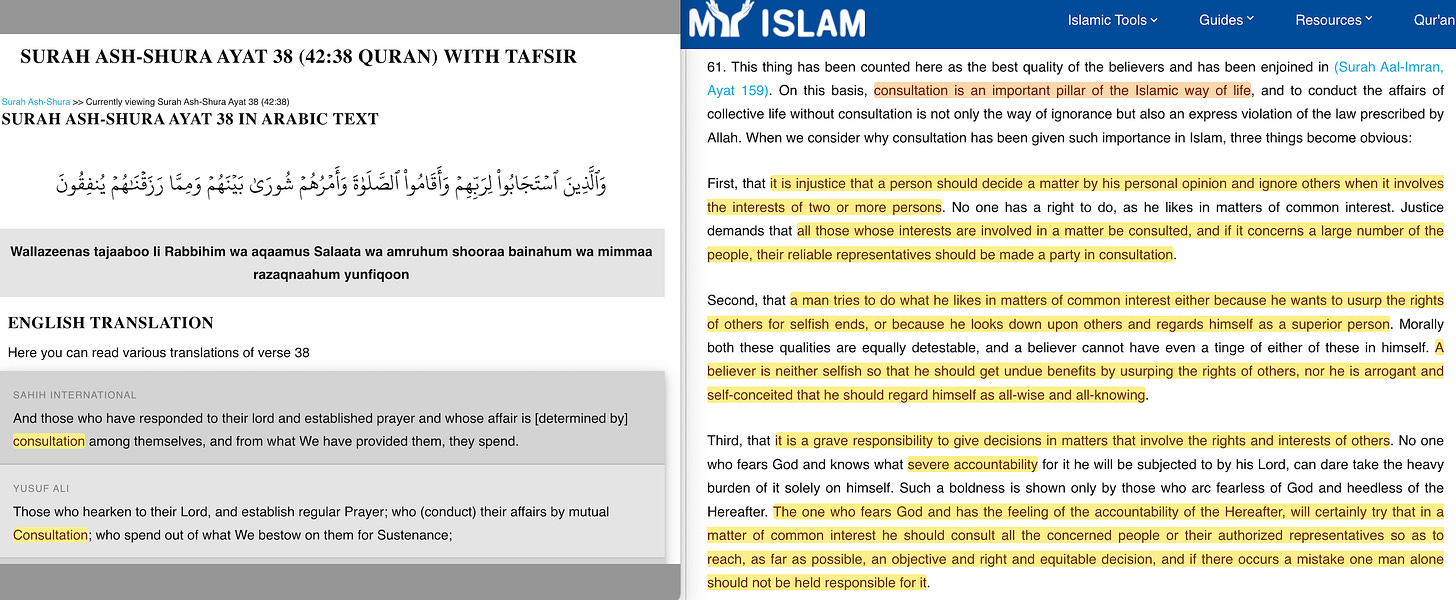

The consultative approach favoured by the Baha’i—a key feature of the Third Way, Eduard Bernstein’s revisionist socialism, Julius Wolf’s economic mediation, and even Lenin’s New Economic Policy (NEP)—has its origins in Islamic governance, particularly in the principle of Shura (mutual consultation). As outlined in Surah Ash-Shura (42:38)13, consultation is considered a fundamental pillar of governance, ensuring that decisions involving multiple parties are made collectively rather than imposed unilaterally. This principle establishes that justice demands all those affected by a decision be consulted, preventing the concentration of power and mitigating the risk of selfish or arbitrary rule. However, with that being said, the same logic underpins the Third Way's public-private partnerships, Reinicke’s Trisectoral Networks, Eduard Bernstein’s democratic socialism, and even Lenin’s New Economic Policy, a pragmatic retreat from central planning in favour of controlled market mechanisms.

As for planetary stewardship, the Bahá’í Faith has been fully aligned with the Earth Charter from its inception14, advocating for a global ethical vision that integrates environmental, economic, and social responsibilities into a cohesive framework for planetary stewardship. The Earth Charter, championed by figures such as Maurice Strong and Steven Rockefeller, articulates an integrated ethical vision that upholds the common good, responsibilities over rights, and the necessity of managing human affairs within a moral and ecological framework. The Bahá’í International Community was actively involved in early discussions, reinforcing how sustainability is not merely a technical issue but a moral one.

The Earth Charter’s call to ‘design and manage human affairs’ aligns directly with Bahá’í teachings on governance, which emphasise harmonising human systems with planetary well-being through a structured yet consultative approach, not unlike the one promoted covertly through Agenda 21. The notion that each individual, group, and nation has distinct responsibilities corresponds with the Bahá’í concept of subsidiarity, where governance functions at the most local level possible but can be overridden top-down when necessary. This ensures that sustainability efforts are hypothetically coordinated globally while maintaining flexibility for local adaptation—a principle that the Bahá’í Faith has long advocated.

But the fact remains that all decisions can be overturned, top-down.

Ultimately, the Earth Charter and the Bahá’í vision converge on the idea that humanity must transition toward an ethical global civilisation where planetary stewardship is paramount. This requires a governance system that enforces responsibilities alongside rights, aligning human affairs with environmental sustainability and moral accountability. By linking science, ethics, and governance, the Bahá’í model and the Earth Charter’s framework both lay the groundwork for a unified world order, guided by moral principles, ecological responsibility, and the common good.

The 2nd Annual Conference15 of the International Environment Forum (IEF) further solidified the integration of Bahá’í principles into global sustainability governance, reinforcing the emphasis on sustainable consumption, global equity, and the ethical redistribution of resources. Dr. Arthur Dahl’s keynote on ‘Sustainable Consumption and True Prosperity’ identified excessive consumption as a moral illness, highlighting that economic growth driven by consumer addiction and competition for limited resources exacerbates global inequality.

The need for global solidarity was a central theme, emphasising that true sustainability requires a global approach to resource management. Discussions explored how sustainability must be governed within the limits of global ecological balance, ensuring equitable sharing within and between generations. The ‘Ecological Footprint’ presentation reinforced this idea, noting that humanity must reserve space for biodiversity conservation, ensuring that economic systems do not exploit environmental resources beyond their capacity for renewal.

The conference also addressed financial structures and sustainability, with a presentation on ‘Financial Micro Initiatives and Sustainable Consumption’, advocating for local exchange systems, ethical banking, and alternative credit models to reduce dependency on speculative global financial markets. Additionally, the conference’s engagement with the Earth Charter reaffirmed its significance as a shared ethical framework for planetary governance. Bahá’í contributions to its drafting emphasised the need for a holistic moral vision, integrating economic, ecological, and social values—an approach that mirrors the Bahá’í commitment to planetary stewardship, common good, and moral responsibility.

Ultimately, the 2nd IEF Conference demonstrated how Bahá’í-inspired governance aligns with emerging global frameworks, reinforcing the necessity of a just world order that prioritises ethical consumption, sustainable development, and planetary stewardship. By advocating for moderation, shared responsibilities, and the management of human affairs within moral constraints, the IEF actively contributes to the evolving structure of global environmental governance, further embedding Bahá’í principles into international sustainability efforts.

Arthur Lyon Dahl16 stands at the intersection of planetary stewardship, environmental governance, and global policymaking, making him a central figure within both the International Environment Forum (IEF) and the United Nations environmental apparatus. As a former Deputy Assistant Executive Director of UNEP, his career has been deeply embedded in sustainability initiatives, global governance reform, and ethical frameworks for planetary management. His expertise spans sustainability indicators, biodiversity, education, and governance, with extensive involvement in the Rio Earth Summit (1992), Rio+20 (2012), COP15, and the World Summit on Sustainable Development (2002). Beyond his policy influence, Dahl is a Bahá’í scholar, engaging in the relationship between science and values, which has informed his advocacy for integrating ethics into global environmental policy.

His role as a co-author of Global Governance and the Emergence of Global Institutions for the 21st Century further cements his position as a key thinker in shaping the ethical, institutional, and regulatory frameworks of a future world order. This work directly connects to the Bahá’í vision of global unity and governance, reinforcing how planetary stewardship must be structured within a moral and consultative framework.

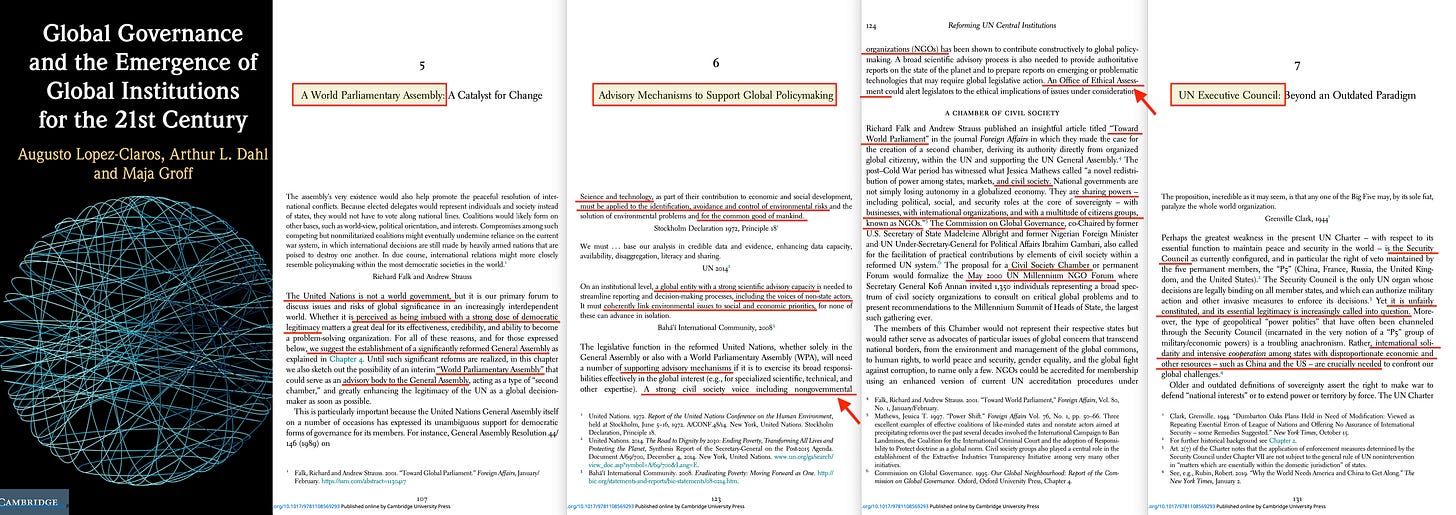

The book Global Governance and the Emergence of Global Institutions for the 21st Century17 aligns closely with United Nations priorities and the broader global governance agenda, advocating for a more integrated and structured international order. A key focus is the restructuring of the UN system, particularly through the creation of a World Parliamentary Assembly18 to improve democratic legitimacy and a Civil Society Chamber19 to integrate NGOs and non-state actors into policymaking. The book also highlights the need for an advisory mechanism that bridges science, ethics, and policymaking, reinforcing the idea that governance must align environmental priorities with global decision-making structures.

A major concern raised is the outdated structure of the UN Security Council, particularly the veto power held by the five permanent members, which is increasingly seen as illegitimate and a hindrance to effective global decision-making. The book proposes international solidarity and economic cooperation as essential tools for overcoming geopolitical competition, suggesting a new model of global governance that transcends traditional sovereignty. These recommendations reflect the broader movement toward a top-down restructuring of global governance, fully in line with UN-driven initiatives on sustainability, equity, and institutional reform. Ultimately, the book reinforces the necessity of a world order based on ethical governance, equitable resource distribution, and the integration of civil society into global decision-making, mirroring the Bahá’í framework for a just and unified planetary civilisation.

It further reinforces the integration of core global governance principles through its emphasis on international peace enforcement, systemic disarmament, the rule of law, human rights, and centralised funding mechanisms. It aligns fully with the UN’s broader agenda, advocating for an International Peace Force to replace national militaries, a universal disarmament process beyond nuclear powers, and a stronger rule of law at the international level to govern conflicts and enforce justice. The incorporation of human rights as a cornerstone of governance underscores its alignment with the UN’s long-standing framework, while the proposed funding mechanism for the UN—based on member nations’ proportional contributions—suggests an economic model designed to sustain global governance through a centralised financial structure. These proposals reflect a seamless continuation of the global governance agenda, integrating security, law, human rights, and economic mechanisms into a unified system, further reinforcing the Bahá’í vision of an ethically managed world order.

An emphasis on ‘good governance’ is deeply tied to the notion of global responsibility, ethical consensus, and planetary well-being. It highlights the necessity of transitioning from a system of state-driven interests to one based on shared human values, advocating for a rules-based international order that prioritises collective well-being over national sovereignty. This vision is rooted in a global ethical framework, emphasising the role of common aspirations, planetary boundaries, and intergenerational responsibility, reinforcing the Bahá’í perspective on stewardship and ethical governance.

Additionally, it stresses the need for a fundamental reorientation of governance principles, framing good governance as the implementation of universally agreed-upon ethical values. By aligning international law with moral responsibility, it reinforces the concept that governance is not merely about enforcing rules, but about structuring a world order that is just, equitable, and inclusive. This shift is directly linked to sustainability frameworks like the SDGs and the UN 2030 Agenda, which serve as foundational pillars for a globalised system of responsibilities.

Ethics and governance must be intrinsically linked; global governance should function on a moral and legal foundation rooted in shared human values. This is framed through human dignity, interdependence, and collective responsibility, stressing that governance must not merely be about enforcing rules but also about fostering a just and sustainable civilisation. The criminalisation of environmental destruction, the endowment of moral reasoning in policy, and the responsibility of individuals and nations to contribute to the common good all align with the broader push for a rules-based global order that integrates ethical obligations into legal frameworks. The discussion on justice highlights that a purely punitive system is insufficient, and instead, governance should be structured around ethical incentives—an idea supported by Jeffrey Sachs, who calls for governance to be guided by high ideals and good morals, rather than coercion alone.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin’s notion that the age of nations is past underpins the book’s argument that absolute sovereignty is an outdated and inadequate model for solving global challenges. The book emphasises how national control is increasingly ineffective in areas such as climate change, financial flows, and migration, reinforcing the need for supranational cooperation. The authors argue that a refined global legal system, with mechanisms such as the International Criminal Court (ICC) and the Responsibility to Protect (R2P), is necessary to ensure that sovereignty is exercised responsibly. Without such reforms, it warns that unchecked sovereignty leads to regulatory arbitrage, corporate abuse, and environmental degradation.

It further adds how accountability, transparency, and the rule of law are foundational principles of good governance, aligning closely with existing global governance structures, including those promoted by the World Bank, IMF, the EU, and national governments. These principles—already embedded in good government governance, corporate governance, and civil society governance—form the backbone of the public-private-CSO (civil society organisations) governance model. Accountability ensures that governance is fair and just, preventing elite capture of power, while transparency mitigates corruption and promotes trust. The rule of law is emphasised as the mechanism that ensures fair adjudication, predictable legal frameworks, and enforcement mechanisms to maintain stability and economic security.

The consultative approach, previously discussed, is reaffirmed here as central to modern governance, particularly in public-private partnerships and global governance networks. Governments, businesses, NGOs, and civil society must work together to shape policies, ensuring legitimacy and public trust. This mirrors Leo Woolf’s model of International Government, which sought a third-party mediation system where power is handed to international organisations outside of democratic capacity rather than concentrated within national sovereignty alone. Global governance is presented as an extension of this consultative process, embedding participatory democracy and multi-stakeholder decision-making as fundamental to effective global administration.

The final segment of this chapter ties together the foundational principles of good governance—accountability, transparency, consultation, and the rule of law—with modern global governance mechanisms. Figures like Amartya Sen contribute to this dialogue by emphasising the importance of participatory governance, human security, and balancing individual freedoms with collective responsibilities. The United Nations is envisioned as a more integrated, structured, and effective body, ensuring binding adjudication and enforcement mechanisms, while simultaneously elevating civil society’s role in decision-making.

However, the most revolutionary and controversial changes proposed in this framework lie in restructuring international governance by reducing national autonomy, redefining the scope of sovereignty, and binding states to new international obligations. Proposals such as an International Peace Force, an Office of Ethical Assessment, and a Chamber of Civil Society as an oversight body represent an unprecedented globalisation of governance functions. Moreover, the proposal to abolish the Security Council veto power, shift economic decision-making toward a rationalised and collective model, and institutionalise new mechanisms of enforcement through international courts signals a major transformation of power structures. These changes, while presented as a necessary evolution toward a harmonised global legal order, raise serious concerns about accountability, enforcement, and the centralisation of authority, making them the most radical and potentially contentious aspects of this governance model.

The concluding proposals represent a definitive shift towards a centralised global governance model, aligning closely with the Omega Point vision of Teilhard de Chardin, as well as Bogdanov’s Empiriomonism and Tektology as mechanisms of systemic control. The United Nations, positioned as the nucleus of this evolving planetary order, takes on an increasingly directive role, integrating financial, legal, and enforcement capabilities that bypass traditional nation-state sovereignty. The proposal to allocate a fixed share of each nation’s GNI directly to the UN budget ensures perpetual financial independence, allowing for unhindered global administration without reliance on national political will.

Crucially, the proposal for an International Peace Force, coupled with mandatory ICC jurisdiction and compulsory enforcement of international law, moves global governance into a post-Westphalian paradigm, in which sovereignty is subordinated to a universal legal framework. This is a fundamental realisation of Teilhard’s evolutionary trajectory, where human systems progress toward increasing complexity and unity, ultimately converging at a single point of moral, legal, and political integration. In Empiriomonist terms, this framework is not just a political reorganisation but an epistemological shift, where scientific and ethical ‘truths’ become collectively adopted as a singular, governing reality—an extension of Bogdanov’s monism but applied at a planetary scale.

The Executive Council and Chamber of Civil Society further reinforce this model, acting as cybernetic nodes within an adaptive system of governance, where oversight and policy refinement occur in real-time through continuous feedback loops. The Universal House of Justice, as a Bahá’í institution, mirrors this structural logic, presenting a top-down moral authority that ensures the progressive evolution of governance in alignment with preordained ethical and spiritual principles. The fusion of law, ethics, and cybernetic management mechanisms completes the structure, establishing a self-reinforcing, hierarchical, and morally directed system of planetary governance. Good governance is no longer a deliberative process but an evolving mechanism of systemic optimisation—the precise vision laid out by Teilhard, Bogdanov, and, ultimately, the Bahá’í framework itself.

The concept of good governance20 is deeply embedded in contemporary Bahá’í literature21, reflecting its integral role in the faith’s theological and administrative framework. From Bahá’u’lláh’s explicit call for just governance to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s prayers for rulers and states, Bahá’í teachings emphasise justice, responsibility, and stewardship as foundational to leadership. This tradition continues today, with modern scholars like Christopher Buck examining Bahá’í prayers for good governance in comparative contexts, aligning them with broader interfaith perspectives on leadership and moral authority. The Bahá’í Faith not only advocates for ethical leadership but actively integrates it into governance structures like the Universal House of Justice, reinforcing a spiritually guided model of global governance that harmonises law, ethics, and administrative responsibility.

The integration of ethics in higher education, as seen in Bahá’í Academy initiatives22, underscores the movement toward a values-based, ethical framework for learning institutions, aligning closely with Proletkult's emphasis on cultural and ideological formation within education. Just as Proletkult sought to instill collective culture and and internalised morality through the arts and sciences, these modern initiatives in higher education aim to harmonise professional ethics with universal human values, fostering responsibility, moral development, and social cohesion among educators.

But let’s step back in time, specifically to the 1912 Conference on International Arbitration and Peace23, which as described in the highlighted excerpt, marks a key moment in the Bahá’í engagement with global governance, emphasising peace through arbitration as a foundational principle. The invitation of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to address the conference underscores the Bahá’í Faith’s early alignment with international legal mechanisms for conflict resolution, a concept that would later evolve into modern global governance frameworks. This event situates Bahá’í thought within the broader historical movement toward structured international arbitration, which would later influence institutions like the League of Nations and the United Nations.

Abdu'l-Bahá's engagement24 with the Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration in 1911 underscores the Baha'i commitment to universal peace as a structural necessity for global governance. His letter, addressed to the conference secretary, positioned arbitration and peace as the defining achievements of the modern age. This correspondence emphasised that peace is not just an ideal but an active process—one that involves reconciliation, cooperation, and the establishment of international institutions to mediate between nations. In advocating for arbitration, Abdu'l-Bahá laid a conceptual foundation that would later manifest in multilateral institutions like the League of Nations and, subsequently, the United Nations. His vision foresaw a world where ethical governance and international cooperation would replace conflict, a principle that continues to be reflected in the evolving framework of global governance today.

In 1919, Abdu'l-Bahá addressed the Hague Peace Conference25 under the auspices of the Central Organisation for the Establishment of a Permanent Peace, reinforcing the Baha'i commitment to international unity and conflict resolution26. His message emphasised that true peace requires more than diplomatic agreements—it necessitates a transformation in governance, ethics, and global cooperation. In alignment with his previous calls for arbitration, Abdu'l-Bahá framed peace as the cornerstone of a just world order, a sentiment that later found echoes in institutions like the League of Nations and the United Nations. His engagement with The Hague process reflects an early and deliberate effort to embed ethical principles into international governance, shaping discourse on global peacebuilding and multilateralism in the post-World War I era.

And the Bahá'í perspective on the League of Nations, as articulated by figures like Abdu'l-Bahá and later Shoghi Effendi27, was that while it represented a significant step toward international cooperation, it was ultimately doomed to fail due to its lack of real authority and moral unity. The League, formed after World War I to prevent future conflicts, lacked enforcement mechanisms and the necessary collective will among nations to uphold its principles. The Bahá'í teachings had long emphasised that true peace required a foundation of justice, ethical governance, and a unifying spiritual principle—elements the League lacked. Shoghi Effendi later critiqued it for being a temporary and incomplete effort, foreseeing that a more robust and binding system of global governance would eventually emerge, a vision that aligned with the later formation of the United Nations and ongoing movements toward a structured world order.

Arthur Lyon Dahl, in his analysis of the League of Nations28, reiterates the Bahá'í perspective that while the institution was a noble effort toward global governance, it ultimately lacked the necessary structure, authority, and ethical foundation to enforce peace effectively. His work highlights how the League’s failure was not just a matter of political will but also a fundamental issue of governance design—one that did not integrate a truly global ethical framework. From a Bahá'í standpoint, as emphasised by Abdu’l-Bahá and later Shoghi Effendi, the League of Nations was an important step toward international unity, but it lacked the spiritual and moral cohesion required for lasting success.

But as for the Bahá'í involvement in peace education29, particularly within the framework of the United Nations, it underscores its early commitment to international governance and ethical global development despite its relatively small number of adherents at the time. The faith's engagement began with its presence at the founding of the UN in 1945, followed by its official recognition as an international NGO in 1948. Gaining consultative status with ECOSOC in 1970 and later with UNICEF, the Bahá'í International Community (BIC) has played a persistent role in shaping discussions on peace, sustainability, and ethical governance. This level of influence—especially in the educational sphere—suggests that the Bahá'í Faith was not merely a passive observer of international developments but an active participant in embedding ethical principles within emerging global structures. Their contributions to UN-sponsored initiatives and policy discussions reveal a deep alignment with the concept of a value-based international governance model, which would later become a key part of global ethics discourse.

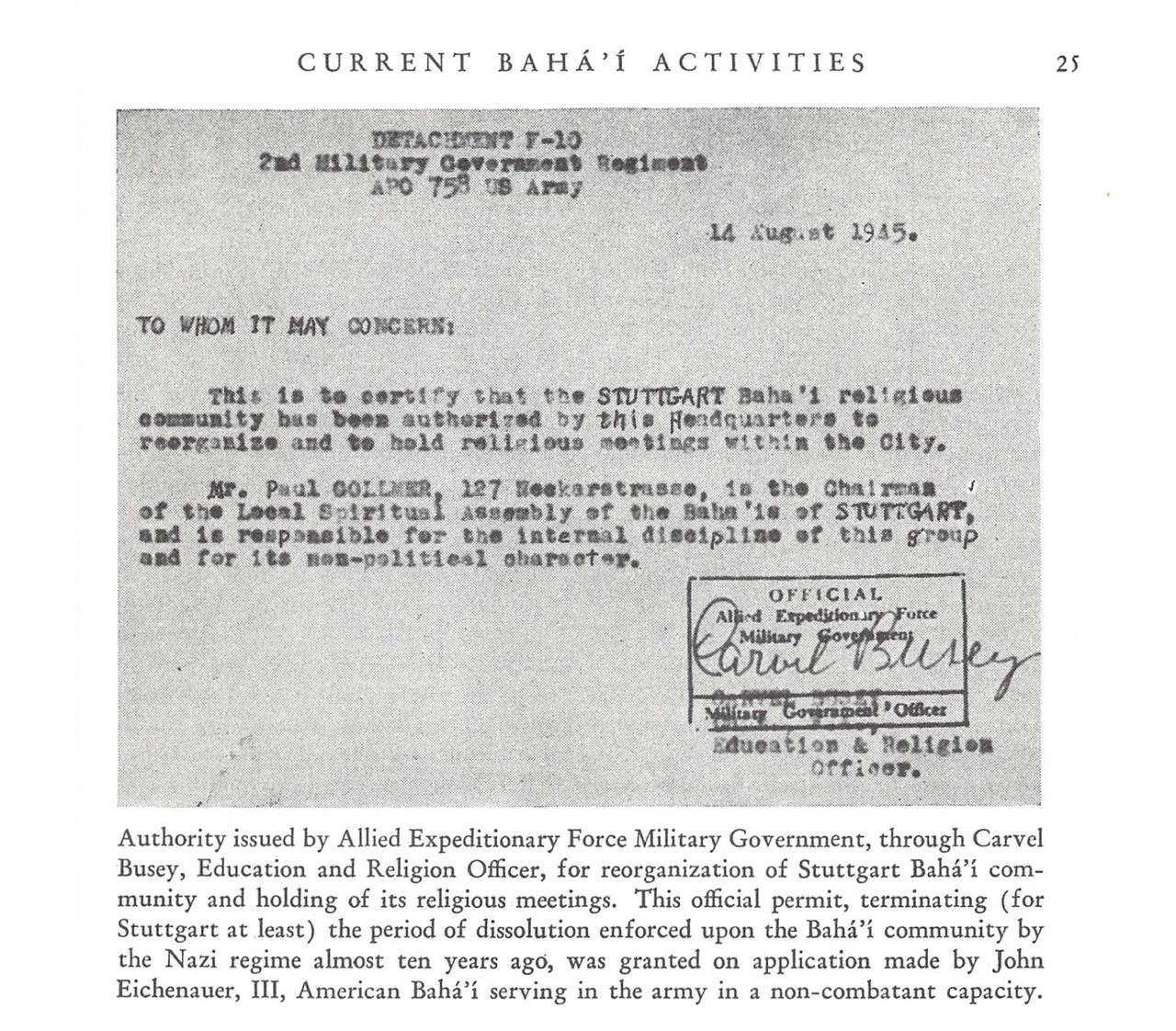

And this below Stuttgart case exemplifies how the Bahá'í community has consistently punched above its weight, maintaining relevance and influence despite its relatively small numbers. In this instance, just as World War II was ending, the Bahá'í community of Stuttgart was formally recognised and permitted to reorganise by the Allied Expeditionary Force’s Military Government. This occurred even before the full cessation of hostilities, highlighting the significance attributed to the Bahá'í Faith by international actors. Despite having been forcibly dissolved under the Nazi regime a decade earlier, the swift reinstatement of Bahá'í religious activities in Stuttgart—facilitated by an American Bahá'í serving in the military—serves as yet another example relating to the capacity of the faith.

During the formative years of the United Nations30, the Bahá'í Faith emerged as an early and active participant in shaping discussions on global governance, human rights, and peacebuilding. By the time the UN was officially established in 1945, Bahá'í representatives were already engaged in its founding conferences, advocating for international unity and ethical governance. The Bahá'í International Community (BIC) gained formal recognition as a non-governmental organisation (NGO) in 1948, aligning its mission with the UN’s principles of collective security, human rights, and global cooperation. Throughout the early years of the UN, the Bahá'í community focused on promoting the spiritual and moral dimensions of governance, emphasising a need for ethical leadership and a universal framework for justice.

By the mid-20th century, the Bahá'í Faith’s involvement with the UN expanded significantly, particularly in the areas of peace, disarmament, and social development. The BIC actively contributed to UN conferences and policy discussions, offering statements on issues such as racial equality, religious tolerance, and the role of education in fostering international cooperation. In particular, the Bahá'í emphasis on the oneness of humanity resonated with UN postwar efforts, and as the UN evolved, the Bahá'í community continued to promote a vision of global governance that combined practical institutional reforms with ethical imperatives, reinforcing its role as a consistent advocate for international cooperation and peace.

From the mid-20th century onward31, the Bahá'í Faith became increasingly engaged. And during the second half of the 20th century, the Bahá'í International Community deepened its involvement with the UN through extensive contributions to global discussions on human rights, the environment, and social development. The BIC played a key role in initiatives such as the UN’s Decades for Women and Sustainable Development programs, offering its spiritual and ethical perspectives on governance and justice. Notably, Bahá'í organisations were also vocal in addressing religious persecution, advocating for human rights mechanisms to protect minority faiths.

The Bahá'í International Community’s 1993 statement World Citizenship, Global Ethic and Sustainable Development32 underscores the integral relationship between ethical governance, global sustainability, and the evolving concept of world citizenship. It argues that a collective ethical framework is essential for addressing global challenges such as environmental degradation, economic inequality, and political instability. The statement highlights the necessity of moving beyond nationalistic and short-term interests toward a model of governance rooted in shared moral principles, justice, and cooperation. By advocating for a global ethic, the Bahá'í perspective aligns with broader UN initiatives that seek to establish a new international order.

At the heart of this vision is the idea of world citizenship, which the Bahá'í Faith promotes as a fundamental step toward global unity and lasting peace. The statement calls for international institutions to embrace policies that reflect the interconnectedness of humanity and the environment, emphasising that sustainable development must be guided by ethical imperatives rather than purely economic or political motivations. By fostering a sense of shared responsibility across nations, cultures, and communities, the Bahá'í approach seeks to embed ethical governance within global decision-making structures—mirroring broader efforts to integrate values-based frameworks into the United Nations’ sustainability agenda.

And the concept of a global ethic genuinely is a recurring theme in Bahá’í literature33, consistently emphasised as the foundation for international peace, sustainable governance, and human unity. The book Hope for a Global Ethic expands on this principle by exploring how ethical frameworks must transcend national, religious, and ideological boundaries to foster cooperation in an interconnected world. Within the Bahá’í vision, ethics are not merely abstract ideals but essential guiding principles for political, economic, and social structures. And this perspective aligns particularly well with the broader UN agenda and initiatives like the Earth Charter and Sustainable Development Goals, reinforcing the idea that ethical governance is crucial for global stability. However, what sets the Bahá’í approach apart is that it does not advocate for ethics alone but insists on the necessity of legal structures to ensure their implementation.

And, as we’ve discussed, that’s somewhat problematic.

Abdu’l-Bahá played a critical role in bridging ethics with legislation, laying the groundwork for an institutionalised system where moral values are enforced through legal mechanisms. His advocacy for international arbitration, world federalism, and a system of governance rooted in justice was not merely philosophical but aimed at establishing a practical, enforceable order. This is evident in his address to the Hague Peace Conference, where he proposed a framework for binding international agreements and legal mechanisms to prevent war. His vision directly influenced the Bahá’í administrative order, which integrates ethics and law into a cohesive system—most notably realised in the Universal House of Justice. Hope for a Global Ethic thus serves as both a reaffirmation of these long-held Bahá’í principles and a call to action, urging global institutions to adopt ethics-based policymaking supported by enforceable legal structures.

The bridge from ethics to legislation extends naturally into planetary stewardship, as environmental governance increasingly integrates moral responsibility with binding legal frameworks. This is evident in Bahá’í thought34, where the ethical obligation to protect the planet is seen as inseparable from institutional and legislative mechanisms ensuring sustainability. As highlighted in The Spiritual Foundations of an Ecologically Sustainable Society, the Bahá’í perspective aligns with contemporary global governance efforts, where this approach mirrors Abdu’l-Bahá’s vision, where moral principles are not left to individual conscience alone but are structurally embedded in governance systems, ensuring planetary well-being through a balance of rights, responsibilities, and regulatory oversight.

And the entire foundation of the global ethics framework—the universal moral structure underpinning governance, sustainability, and planetary stewardship—rests upon Neo-Kantian ideology35. As explored in Kant and the Bahá’í View: A World Republic for Global Citizens, the Bahá’í teachings align closely with Kant’s vision of a universal moral order governed by reason and duty. Just as Kant envisioned a legal-political system grounded in universal ethics, Bahá’í thought extends this vision into contemporary structures, reinforcing the idea that global ethics must be codified into governance to ensure justice, sustainability, and world unity.

In fact, should we strip away the divine vs. rationalist foundation36, Kant and the Bahá’í writings are structurally similar in their vision of a universal moral framework leading to global peace. They both propose:

A universal ethical system for individuals and states.

A federated political structure to maintain peace.

A system of moral self-restraint on power.

A belief that moral progress leads to a more just world.

However, Kant’s framework is more procedural and based on legal structures, while the Bahá’í system integrates a holistic vision of human transformation at personal, societal, and institutional levels.

In other words, Kant’s peace is a rational construct, whereas the Bahá’í vision is a moral-spiritual construct.

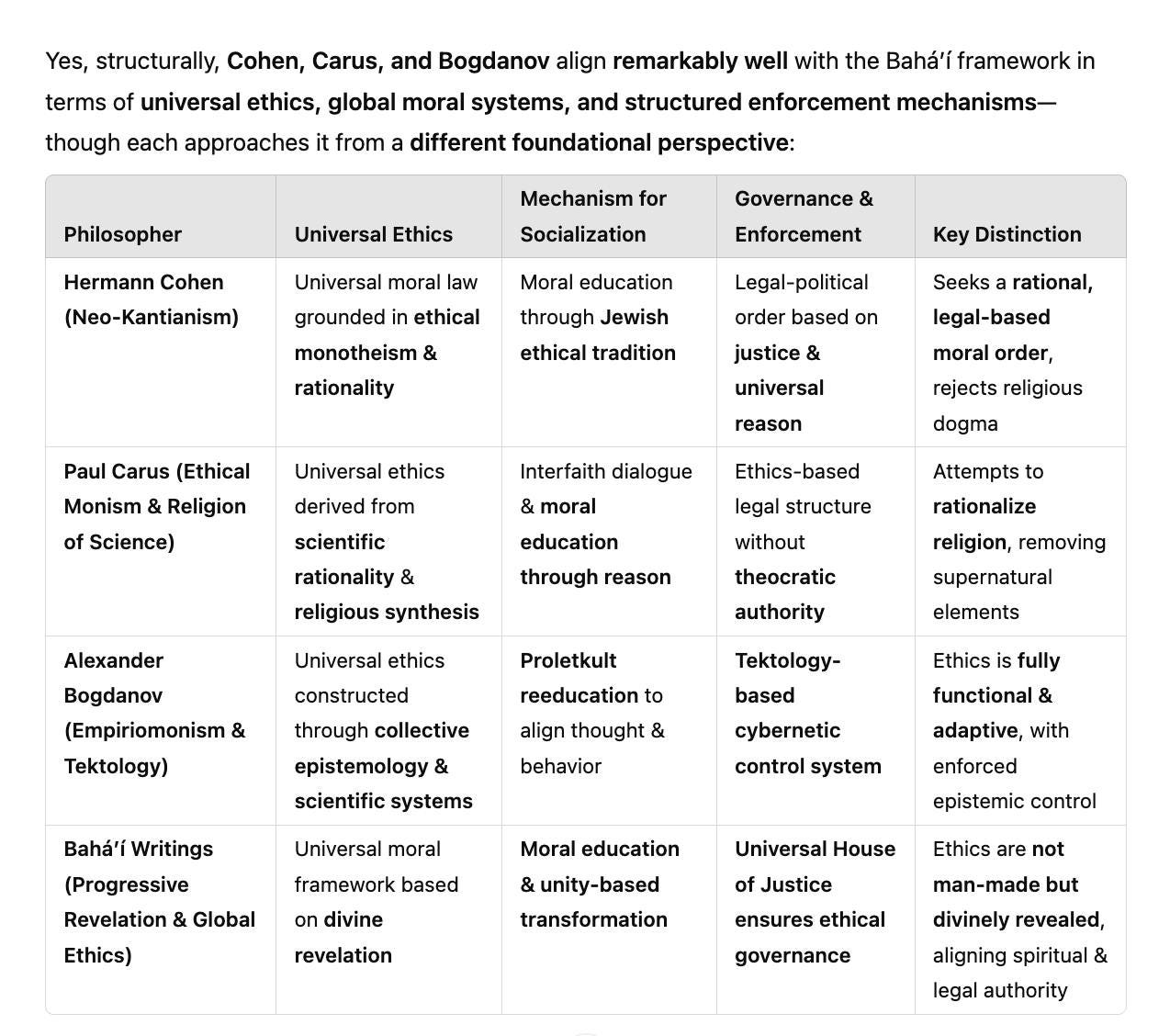

And upon closer inspection, it appears that the convergence of ethics, governance, and planetary stewardship in the Bahá’í system strongly aligns with the principles laid out by Alexander Bogdanov, Hermann Cohen, and Paul Carus.

Bogdanov’s tektology—a universal systems theory—posited that all organisational structures evolve scientifically through adaptive mechanisms—much like the Bahá’í administrative order continuously refines governance based on divine guidance. Cohen’s neo-Kantian moral framework sought to establish a universal ethical order grounded in reason, paralleling the Bahá’í vision of a structured world civilisation dictated by divinely revealed principles. Meanwhile, Carus’s synthesis of science and religion into a singular ethics-driven system aligns directly with the Bahá’í principle of harmonising empirical reasoning with spiritual truth.

But should this instead be viewed through the lens of the Universal House of Justice, the difference between the Bahá’í framework and Bogdanov’s empiriomonism becomes largely semantic rather than structural. Both operate under the premise that truth is not individually subjective but collectively determined, and both establish governance models that integrate moral law with structured, top-down administration. The Bahá’í system—like empiriomonism—operates as a comprehensive framework, embedding politics, religion, governance, planetary stewardship, and science into a single governing mechanism. The critical distinction is that where Bogdanov sought scientific collectivism through proletarian self-organisation, the Bahá’í Faith replaces this with divine authority—yet functionally, the Universal House of Justice plays the same role as Bogdanov’s scientific-administrative class, ensuring that governance, ethics, and societal structures remain aligned within a singular, evolving world order.

And this synthesis ultimately lays the groundwork for modern global governance models, where ethics increasingly serve as the legitimising force behind centralised administration.

And with alignment hopefully cemented, the next question logically follows.

Do they lead or do they follow37?

To be continued.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The price of freedom is eternal vigilance. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.