The Circular Economy

The conventional narrative presents Karl Marx as the champion of the working class, developing scientific socialism to replace the utopian schemes of earlier socialists. Yet, Marx's organisational behaviour from 1842 to 1850 reveals somewhat the different story: the deliberate infiltration and capture of existing working-class movements, followed by the systematic elimination of alternative leadership and the concentration of ideological control in the hands of a self-appointed vanguard.

This was not the organic development of superior theory, but an operation to redirect worker grievances toward centralised administration disguised as liberation.

The League of the Just1, which Marx entered in 1847, represented a thriving international network of largely German artisans — tailors, woodworkers, and craftsmen — whose egalitarian motto, ‘All men are brothers’, reflected genuine ideals. What Marx achieved was not to create a new movement, but to systematically transform an existing one through information control, resource advantages, procedural manipulation, and strategic purges.

The resulting theoretical framework — from the Communist Manifesto through Capital to the Gotha Programme — provided not an analysis of capitalism but a technical manual for comprehensive social control.

The Infiltration (1842-1846)

Marx's path toward communism began through intellectual mentorship. In 1842, Moses Hess drew Marx and Engels toward communist ideas2, and Marx began surveying the existing landscape of socialist thought — studying Proudhon, Dézamy, and other currents already active across Europe. By 1845, Marx and Engels had established contacts with German exiles and British Chartists during their London visit, with Engels fresh from completing his Condition of the Working Class in England3. This was Marx's introduction to an already lively ecosystem of working-class organising.

The turning point came in early 1846 with the establishment of the Brussels Communist Correspondence Committee45. Far from being a simple communication network, the Committee functioned like what could in contemporary terms be described as an ‘information clearinghouse’ — a central node that filters information, certifies ‘correct’ texts and interpretations, and coordinates responses across scattered groups6. Surviving correspondence shows the Committee operating as a disciplinary nerve center, capable of launching coordinated attacks on rival currents while presenting such interventions as naturally emerging consensus.

The core of the Brussels group met twice weekly under the cover of a workers’ educational society, yet the majority were bourgeois: Freiligrath, Hess, Edgar von Westphalen, Weydemeyer, Seiler, Heilberg, Gigot, Ernst and Ferdinand Wolff, Ernst Dronke — and Weitling himself among a few artisan voices7. With Gigot and Engels assisting, Marx ran a multilingual correspondence from Brussels seeking a single line all factions would accept — and was ‘eager to purge the party of its ‘sentimentality’, explicitly targeting Weitling’s artisan communism and Hess’s philosophical variant. Proudhon refused to cooperate; Louis Blanc stayed in touch.

In London, the split was already visible before Brussels. During Weitling’s brief absence, Karl Schapper attacked his core schemes — the Tauschbank and Kommerzstunden8 — and the society then voted to shelve such proposals in favour of discussing Feuerbach’s Religion of the Future9 and any ‘scientific’ questions members wished to introduce. It marked a clear win for Schapper’s camp and foreshadowed the Marxian turn from practical worker schemes to theory-first orthodoxy10.

The Committee's power became visible in April-May 1846 with the ‘Circular against Kriege’11. Hermann Kriege, a German communist active in America, had been developing what Marx and Engels dismissed as ‘true socialism’ — an approach emphasising moral appeals and gradual reform. The Circular represented the first systematic use of the Brussels hub to police ideological boundaries beyond Germany itself, demonstrating the Committee's reach and its willingness to enforce doctrinal conformity through coordinated denunciation.

The Committee’s boundary-policing was immediately visible in the Circular against Kriege: Weitling alone refused to sign12, arguing for tactical leeway in America, yet copies were dispatched to England, France, Germany, and the United States and the indictment ran in the Westfälische Dampfboot. Moses Hess sided with Weitling and soon broke with Marx and Engels over the affair13.

The Confrontation (Spring 1846)

The Brussels Committee's most significant early operation targeted Wilhelm Weitling, the League of the Just's most influential theorist14. Weitling had already developed sophisticated critiques of property and money in works like Guarantees of Harmony and Freedom15 (1842), which Marx himself had praised as ‘the brilliant literary debut of German political literature’16. Yet when the two men met in Brussels in spring 1846, Marx's attitude had transformed entirely17.

Pavel Annenkov18, a Russian observer present at their crucial encounter, recorded Marx's systematic humiliation of Weitling19. Marx demanded theoretical justification for Weitling's practical organising success, arguing that workers who had ‘lost their jobs and their crust of bread’ following Weitling's activities deserved to know ‘with what fundamental principles do you justify your revolutionary and social activity’20. When Weitling defended his practical achievements — gathering ‘hundreds of people together in the name of the idea of justice, solidarity, and brotherly mutual aid’ — Marx responded with personal attack rather than intellectual engagement.

The confrontation climaxed when Marx ‘slammed his fist down on the table so hard that the lamp on the table reverberated and tottered’ while shouting ‘Ignorance has never yet helped anybody’21. This was not theoretical debate but deliberate intimidation, designed to force Weitling into defensive mode and shift focus from his organising success. The pattern revealed Marx's operational method: when existing working-class leaders defended their practical achievements, Marx responded with personal attack and conversation termination rather than intellectual engagement.

The Resource Asymmetry

Weitling's letter to Moses Hess on March 31, 184622, provides crucial insight into the dynamics underlying Marx's success. ‘Without money Marx cannot criticise and I cannot defend myself’, Weitling observed, identifying the fundamental imbalance that would determine the outcome of their conflict. While Weitling advocated direct action to ‘influence the people and, above all, to organise a portion of them for the propagation of our popular writings’, Marx opposed this approach to worker organising, being ‘strengthened by their rich supporters’.

The letter captures Weitling's recognition that Marx's faction intended to ‘publish splendid systems in well-financed translations’, contrasting sharply with his own resource constraints. ‘Rich men made him editor, voilà tout’, Weitling noted, identifying Marx not as an authentic working-class leader but as an intellectual dependent on wealthy patrons. Most significantly, Weitling recorded Marx's strategic position that ‘the realisation of communism in the near future was out of the question, and that first the bourgeoisie must be at the helm’ — revealing Marx's opposition to immediate worker organising in favor of long-term political positioning.

Marx’s 1846–47 behavior wasn’t a glitch. In private he spat racist and antisemitic abuse — calling Lassalle a ‘Jewish n-’23 (1862) — and later flirted with race-ranking à la Trémaux24. He lived on Engels’s remittances25 while blowing deadlines (the League’s 1848 Manifesto ultimatum) and torching time on 300-page vendettas like Herr Vogt26. In committees he defaulted to centralise-and-expel — culminating in the Hague (1872) booting of Bakunin and Guillaume27. Even the home front is ugly: the Helene Demuth paternity mess dogs the household (attributed to Marx by some, disputed by others)28. Add the recurring ‘carbuncles’ he himself cited to explain work stalls and a pattern snaps into focus29: contemptuous tone, dependency, procedural hardball, and a reflex for concentrating power. Seen against that record, Brussels wasn’t a one-off but Marx unmasked.

The Systematic Purges (1846-1847)

Armed with resource advantages and institutional control through the Brussels Committee, Marx and Engels began systematic elimination of alternative leadership30. Engels' private correspondence during this period reveals the true attitude of the Marx faction toward working-class members. In letters to Marx, Engels consistently referred to League members as ‘those fools’, ‘those asses’, and ‘those stupid workers who believe everything’, plagued by ‘drowsiness and petty jealousy’. Engels boasted that he was able to ‘put it over’ with some members and ‘bamboozled’ others during his manipulation campaign31.

After Brussels, Engels went to Paris ‘to break whatever influence Weitling still had’, painting him as reactionary, even insinuating he hadn’t authored his own books32. He pushed to expel the ‘little tailor clique’, reporting with satisfaction that the carpenters wouldn’t follow Weitling — and later mocked London journeymen as ‘asses’ in a letter to Marx. It’s a clean window into the private contempt that accompanied the organisational clean-out.

The purges extended across multiple countries and targeted all significant alternatives to Marx's line. Karl Grün, a populariser of Proudhon's ideas in Germany, was accused of embezzling 300 francs on flimsy grounds despite substantial ideological alignment with Marx's stated positions33. When Grün's supporters explained they had raised the money themselves and considered it as a loan, Marx ignored the clarification and proceeded with systematic expulsions34. As historian Jonathan Sperber noted, ‘Ideological differences do not entirely explain the vigour of Marx's attacks on Grün, since there was a lot in Grün's work on French and Belgian socialism that was congenial to Marx’.

Moses Hess, who had been Marx's mentor, was later targeted for expulsion simply for siding with Weitling during the Brussels confrontation. The scale of the purges was extensive: ‘supporters of Weitling, Proudhon35 and Karl Grün [were] expelled or forced to leave’ across Switzerland, Hamburg and Leipzig as well. In Paris, the decimation was particularly severe — ‘only 30 members of the League were left in Paris’ with ‘only two members survived in one Paris group of the League’36.

Engels celebrated the organisational destruction: ‘The remainder of the Weitlingites, a little clique of tailors, is on the point of being thrown out’. This language reveals systematic contempt for the very workers Marx claimed to represent — they were obstacles to be deceived and expelled, not comrades to be educated or convinced.

Formal Centralisation (1847)

Having decimated alternative leadership, Marx and Engels next moved to formalise their control through constitutional changes. The First Congress in June 1847 transformed the League of the Just into the Communist League, replacing its democratic motto ‘All men are brothers’ with ‘Working Men of All Countries, Unite!’37

More significantly, the new Rules established a Central Authority above a hierarchical structure of Districts, Circles, and Communities — concentrating decision-making power in the hands of those who controlled the center.

Parallel to organisational centralisation came doctrinal standardisation. Engels drafted two catechisms: the ‘Draft of a Communist Confession of Faith’38 in June 1847, followed by the expanded ‘Principles of Communism’39 in October-November 1847. These documents replaced pluralistic debate with standardised question-and-answer formats, establishing ‘correct answers’ on key theoretical and strategic questions. This served as ideological gatekeeping — allowing the center to determine who possessed adequate theoretical understanding to participate in decision-making.

Procedural Manipulation (Late 1847)

Even after organisational restructuring and ideological standardisation, Marx and Engels continued to employ procedural manipulation to maintain control. When the Paris groups democratically commissioned Moses Hess to write a program and approved it by a large majority, Engels circumvented their decision by sending ‘his own text, and not that of Hess, be sent to London contrary to the members' votes and as Engels admitted 'behind their backs.'‘ Engels worried that ‘not a soul must notice this or we shall all be deposed and there will be an unholy row’40.

This procedural bad faith continued through the Second Congress, where days of violent disagreement over a programme preceded the eventual commission of Marx to write what became the Communist Manifesto. The ‘unanimous’ decision to commission Marx reflected not broad worker consensus but the procedural exclusions and manipulations that had narrowed the electorate to those willing to accept Marx's leadership.

Even after being commissioned to write the Communist Manifesto, Marx required external pressure to complete the task. The Central Committee was forced to issue an ultimatum giving Marx until February 1, 1848, to deliver the text, warning that ‘further measures will be taken against him’ if he failed to meet the deadline41. The Manifesto finally appeared in London in February 184842, not as the organic expression of working-class consciousness, but as a document produced under institutional pressure after systematic elimination of alternative voices.

Continued Resistance (1848-1850)

Marx's organisational manipulations did not eliminate worker resistance entirely. In Cologne in 1848, Marx clashed with Dr. Andreas Gottschalk and the Workers' Association over revolutionary strategy. When Marx found himself in a minority, he responded by dissolving the Central Committee and pivoting toward a broader democratic coalition with bourgeois elements. Gottschalk's public criticism cut to the heart of Marx's approach:

You have never been serious about the emancipation of the repressed. The misery of the worker, the hunger of the poor has for you only a scientific, a doctrinaire interest... You do not believe in the revolt of the working people.

At Berlin’s ‘Congress of Democrats’, heavy with bourgeois delegates, Weitling’s immediate-revolution line won little traction: his proposal for equal pay drew raucous laughter, and when he pressed for declaring the communist state at once, the chair rebuked him for ‘theoretical quarreling’43.

The split became permanent in 1850, when a bitter quarrel led to a split, with Marx and Engels on one side and Karl Schapper and August Willich on the other. The conflict centered on revolutionary strategy — Schapper and Willich wanted immediate action while Marx advocated long-term organisation. This division reveal that original working-class leaders never fully accepted Marx's methods or timeline, maintaining their commitment to immediate worker empowerment rather than theoretical preparation for future revolution.

The Theoretical Codification (1875-1917)

Marx's organisational methods developed into later works that provided blueprints for comprehensive social control. The Critique of the Gotha Programme44 (1875) outlined a system of ‘labour certificates’ tied to centrally audited work time — creating individual dependency on state-controlled distribution systems45. Crucially, these differed from the circulating ‘labour money’ schemes Marx had earlier criticised in Proudhon and Owen. Where those utopian proposals sought to reform market exchange through time-based currency, Marx's labour certificates would not circulate at all, functioning instead as non-transferable ration entitlements that prevented independent economic coordination and required all consumption to flow through central accounting.

Capital Volume III46 (1894) analysed ‘money-dealing capital’ that ‘specialises in the technical operations of handling money (payments, collections, bookkeeping, etc.) for the capitalist class as a whole’. This analysis provided the theoretical foundation for understanding how centralised payment systems could become instruments of social coordination — transforming financial infrastructure into administrative control mechanisms.

Lenin's State and Revolution47 (1917) synthesised these insights into operational doctrine: ‘The whole of society will have become a single office and a single factory’ under ‘universal accounting and control’. This represented the mature expression of the centralisation program that Marx had pioneered in his organisational work — replacing market coordination with administrative management while maintaining the rhetoric of liberation.

Lenin thus makes explicit what had been implicit in Marx and Engels: liberation means universalisation of book-keeping. In State and Revolution, ‘accounting and control’ become the essence of the first phase of communism, binding every citizen into the ledger of a single ‘factory-office’. The abolition of money does not abolish measurement — it transforms it into total surveillance of flows and entitlements. This was already foreshadowed in Marx’s Grundrisse48, where automation and the end of value imply continuous monitoring of production and consumption in kind. Far from withering away, the state is reborn as a statistical organism: society itself becomes the spreadsheet.

In fact, what Lenin expressly states is this:

For when all have learned to administer and actually to independently administer social production, independently keep accounts and exercise control over the parasites, the sons of the wealthy, the swindlers and other "guardians of capitalist traditions", the escape from this popular accounting and control will inevitably become so incredibly difficult, such a rare exception, and will probably be accompanied by such swift and severe punishment… that the necessity of observing the simple, fundamental rules of the community will very soon become a habit.

Then the door will be thrown wide open for the transition from the first phase of communist society to its higher phase, and with it to the complete withering away of the state.

The transition to the final stage of communism — the withering away of the state — will take place when everything is fully accounted and controlled. However, as we saw in the Grundrisse, this will take place as society is progressively automated.

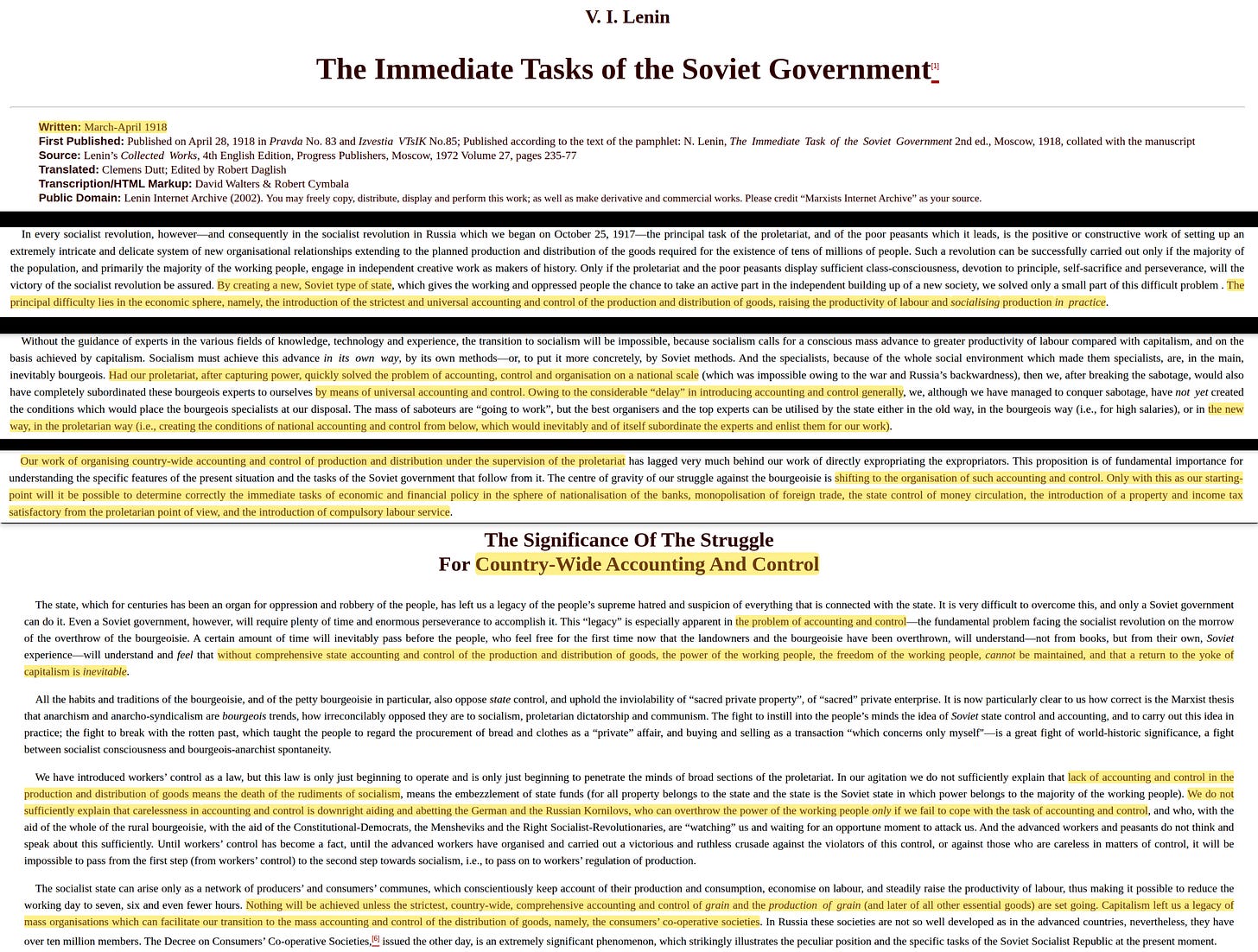

This is not a one-off. In ‘The Immediate Tasks of the Soviet Government’49 from April, 1918, ‘accounting and control’ is repeated throughout, inclusive in mention of economics:

By creating a new, Soviet type of state, which gives the working and oppressed people the chance to take an active part in the independent building up of a new society, we solved only a small part of this difficult problem . The principal difficulty lies in the economic sphere, namely, the introduction of the strictest and universal accounting and control of the production and distribution of goods, raising the productivity of labour and socialising production in practice

To this end, they even seek to engage the finest ‘experts’:

… in the new way, in the proletarian way (i.e., creating the conditions of national accounting and control from below, which would inevitably and of itself subordinate the experts and enlist them for our work).

These ‘stars of the bourgeois intelligentsia’ should participate voluntarily in their work, which seeks to introduce universal book-keeping:

The introduction of work and consumers’ budget books for every bourgeois, including every rural bourgeois, would be an important step towards completely “surrounding” the enemy and towards the creation of a truly popular accounting and control of the production and distribution of goods

The bottom line is this:

Nothing will be achieved unless the strictest, country-wide, comprehensive accounting and control of grain and the production of grain (and later of all other essential goods) are set going. Capitalism left us a legacy of mass organisations which can facilitate our transition to the mass accounting and control of the distribution of goods, namely, the consumers’ co-operative societies

All essential goods are meant to be monitored. Comprehensive surveillance so they can monitor every node and perform comprehensive supply-chain analysis (Bogdanov) — a method later developed into Leontief’s input-output analysis, shifted into McNamara’s PPBS in 1961, and presented through Boulding’s Spaceship Earth as closed General Systems Theory modelling, which through Pearce/Turner became the Circular Economy in 199050.

Yet, Marx’s Grundrisse51 outlines a future society where machinery progressively displaces human labour — the famous ‘fragment on machines’52 where automation becomes the decisive productive force. In this world, the traditional role of money disappears, replaced by global surveillance of production and circulation of all materials of importance — the Circular Economy53.

Lenin, writing half a century after Marx, makes this logic explicit: the ‘first phase of communism’ is nothing other than the introduction of universal accounting and control, administered by all and inescapable for anyone. The promised withering of the state thus depends on the full visibility of every action, every flow, every person.

To grasp the ethical foundation of this logic, we can turn to Moses Hess, who had already argued that communism required nothing less than the abolition of selfishness itself. In his 1845 essay The Essence of Money54, Hess called money ‘human value expressed in figures … the mark of our slavery’. For Hess, money embodies egoism itself, transforming every personal desire into a quantified exchange and every relationship into a transaction. Communism, thus, is not simply the end of property but the elimination of ‘selfishness’, the subordination of all private desires to the collective ideal. Independence, in this sense, is pathological, a residue of bourgeois egoism.

By abolishing money, communism abolishes the medium in which selfishness operates — but only by demanding total transparency of life through comprehensive surveillance. Hess thus provides the ethical grammar that Marx and Lenin later developed into technical blueprints of automation, accounting, and control.

In each case, the promise of emancipation rests on the same premise: only when everything is ‘accounted and controlled’ can selfishness finally be destroyed and the final stage of communism become a reality.

Consequently, what contemporarily presents as neutral ‘governance by indicators’ — SDG indicators55, ESG scoring, risk models, programmable entitlements — is the maturation of a 19th–20th century arc:

Hess supplies the ethic (abolish selfishness — dissolve private desire into the collective).

Engels operationalises legitimacy through numbers (statistics as privileged truth).

Marx furnishes the structural horizon (automation displacing labour; coordination shifting from prices to administered flows).

Lenin codifies the method (universal accounting and control as the first phase of communism).

Bogdanov then systematises it with Tektology (society as an organisable system whose stability is achieved by measurement, feedback, and hierarchical coordination).

Run a few generations forward, and you get contemporary indicator governance56 — rule legitimated and enforced by metrics produced through comprehensive global surveillance producing statistics for the Circular Economy57.

Contemporary Resonance

Contemporary ‘determinants’, ‘indicators’, and ‘metrics’ are not merely tools but increasingly the governing norm. The ethical demand to eliminate selfishness (Hess) pairs with the supremacy of statistics (Engels), the structural promise of automated abundance (Marx), and the political doctrine of universal book-keeping (Lenin), all formalised as systems control (Bogdanov). The result is a governance architecture where numbers do not describe society — they administer it, and where freedom is continuously redefined as compliance with centrally curated measures.

Marx's methodology thus finds disturbing parallels in contemporary developments around programmable digital currencies and algorithmic governance. Just as Marx's Brussels Committee functioned as an information bottleneck that certified ‘correct’ texts while marginalising dissent, contemporary platform gatekeepers shape discourse through ranking algorithms and content moderation policies.

The labour certificates Marx envisioned — non-circulating entitlements tied to central ledgers — parallel the programmable features of central bank digital currencies that enable transaction-level policy enforcement58 which Technocracy, Inc proposed in the 1930s.

Less attended but equally significant is the methodological template Marx and Engels established through their reliance on statistics. Engels’ Condition of the Working Class in England framed mortality tables, factory inspector reports, and sanitary data as the privileged language of truth — a posture Marx extended throughout Capital by embedding Blue Book tables and wage series into his critique, a claim that social reality could be abstracted into indicators and administered from above. In displacing life testimony with quantitative representation, they laid the groundwork for a politics where legitimacy flows to whoever controls the measurement apparatus.

That idea finds its echo in the present. Just as Marx’s ‘scientific socialism’ clothed ideology in the neutrality of numbers, today’s governance regimes justify intervention through SDG metrics, ESG scores, and epidemiological dashboards. Central banks and supranational bodies inherit not only Marx’s conception of non-circulating labour certificates but also his reliance on statistical authority: the belief that human freedom can be translated into data points and managed through central accounting. In both cases, the promise of science masks the reality of control59.

Conclusion

Marx's contribution to political theory was not the critique of capitalism but the perfection of centralised control disguised as liberation. Through systematic infiltration of existing working-class movements, elimination of socialist leaders, and development of sophisticated theoretical justifications for comprehensive surveillance, Marx created the intellectual framework for total social administration.

Marx’s takeover pattern has remained consistent across centuries:

Capture information channels

Standardise acceptable discourse

Eliminate alternative leadership

Implement control through indispensable infrastructure.

The promise is always liberation — the result is always administration.

The ‘scientific socialism’ that emerged from this process was neither scientific nor socialist in any meaningful sense. It was a sophisticated control system that channeled genuine working-class desires into support for unprecedented centralisation of power. The temporary ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ could never wither away because Marx designed it to be structurally indispensable — once alternative coordination mechanisms were destroyed, the central authority became permanent regardless of its ideological self-description.

Understanding Marx's manipulative methodology becomes essential as digital technologies enable the comprehensive monitoring and control systems he envisioned. The pattern remains relevant wherever political movements promise liberation through expanded centralised authority. Marx's true genius lay not in understanding capitalism but in understanding how to make total centralisation appear as inevitable progress — a lesson that continues to find application in contemporary efforts to transform human freedom into administrative permission through HDI indicators60, the SDG indicators61, Aichi Targets and others.

In short: the statistics that legitimated Marx and Engels’ vanguardism matured into today’s indicator rule — managed by central banks and allied technocracies — where numbers do not merely describe society; they govern it.

Contemporary governance by indicators, determinants, and metrics is consequently not a recent innovation but the direct maturation of Hess’s ethic of dissolving individuality, Engels’s statistical empiricism, Marx’s automation and abolition of money, and Lenin’s doctrine of universal accounting — systematised through Bogdanov’s vision of society as a controllable system.

Content is free, links are for paid subscribers.