Patterns of Capture

How Systems Theory Explains Control

Systems theory isn't abstract mathematics — it's the grammar behind everything that surrounds us, from the internet packets carrying this text to the banknotes in your wallet, from the ecosystems outside your window to the institutional frameworks that govern them. Understanding systems theory means understanding the deep structures that shape power and control in our world.

At its heart lies a fundamental tension between two visions of organisation: Ludwig von Bertalanffy's networks and Kenneth Boulding's hierarchies. Bertalanffy saw systems as webs of interconnected nodes, robust through distribution. Boulding saw the necessity of layered organisation, coherence through structured levels.

This tension explains why clearinghouses exist, why they capture power, and why the question of control appears to haunt every system we build including governance.

Bertalanffy: Networks That Heal Themselves

Ludwig von Bertalanffy's General Systems Theory emerged from biology but became something far more ambitious — a science of organisation itself. For Bertalanffy, systems were fundamentally about flows: matter, energy, and information moving through networks of interconnected elements. What mattered wasn't the individual components but the relationships between them, the patterns of exchange that kept the whole alive.

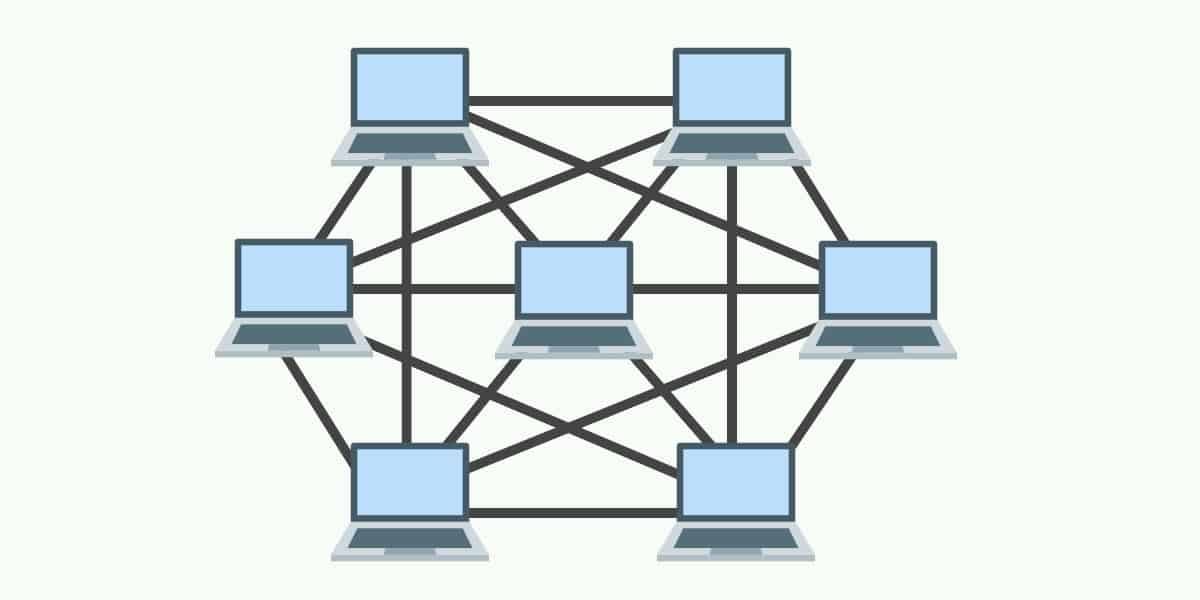

Consider ARPANET in its original conception — packets of information finding their own routes through a mesh of connected nodes. No single computer controlled the flow; strength came from redundancy, from the network's ability to route around damage. This was Bertalanffy's vision made manifest: an open system maintaining itself through constant exchange with its environment, stable not through rigid control but through dynamic equilibrium.

Cash transactions follow the same principle. When you hand over a banknote, you're engaging in peer-to-peer value transfer without requiring permission from any central authority. The network of users maintains trust through distributed verification — millions of people checking authenticity, accepting value based on shared recognition. No single node rules; strength comes from the distributed nature of trust itself.

Ecosystems operate by identical logic. Energy flows from sun to producers to consumers to decomposers, with no central planning authority dictating outcomes. The system's stability emerges from complex webs of relationships, from feedback loops that self-regulate without external control. When something changes, everything else adapts organically.

For Bertalanffy, this distributed approach wasn't just better — it was more alive. Open systems could learn, evolve, and heal themselves. The network wasn't just a model; it was a superior way of organising the world.

Boulding: The Skeleton of Hierarchical Control

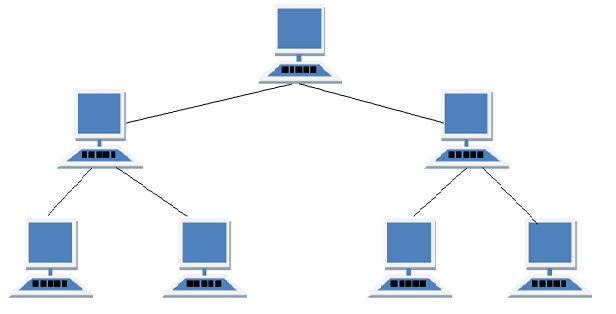

Kenneth Boulding recognised the power of Bertalanffy's insights but believed organisation required not just connection but a hierarchy. His 'Skeleton of Science' built upon Bertalanffy's flat networks by adding recursive layers — frameworks supporting machines supporting organisms supporting societies supporting symbolic systems. Each level emerged from but transcended the one below.

Picture the same ARPANET, but now consider what makes it possible: the physical layer of cables and routers, the protocol layer that governs data transmission, the application layer where programs operate, the user layer where humans interact, the institutional layer where organisations coordinate. Each level follows its own rules while depending on the levels beneath. The hierarchy isn't domination but emergence — higher-order patterns arising from lower-order interactions.

This differs from simple stacking. Boulding's hierarchies are recursive — like Russian dolls, each level repeats the same organisational logic at higher complexity. A cell contains molecular networks; an organism contains cellular networks; an ecosystem contains organismal networks; a society contains ecosystem networks. The same basic principles of systems organisation repeat at every level, but with increasing sophistication.

Boulding saw hierarchical organisation as inevitable for coherence. Without levels of organisation, complex systems would collapse into chaos. For Boulding, hierarchy was simply how complexity organised itself — not a moral question but a structural necessity. Higher levels of organisation emerged naturally from lower ones and necessarily controlled them to maintain systemic stability. This wasn't domination but mechanical function: each level operated according to its own imperatives while constraining the levels beneath it.

The Emergence of Mediating Power

When Bertalanffy's networks meet Boulding's hierarchies certain nodes acquire mediating power. These become clearinghouses — institutions that route flows, certify trust, and extract value from their position between levels or between different parts of the network.

Finance

Financial clearinghouses demonstrate this pattern clearly. The Bank of England began as a private bank but gradually became the mediator between the government's need for credit and private banks' need for legitimacy. It cleared payments, managed reserves, and set standards that other banks had to follow. From this mediating position, it could influence not just individual transactions but the entire monetary system. The Bank for International Settlements took this pattern global, becoming the clearinghouse for central banks themselves.

Information

Information clearinghouses follow identical logic. The Domain Name System began as a simple directory, mapping human-readable addresses to machine-readable numbers. But DNS root servers became chokepoints, controlling which websites could exist on the global internet. ICANN, the organisation managing DNS, wields power over global communications despite being technically just a private nonprofit. Google achieved similar mediating power differently — by indexing the web's chaos into searchable hierarchies, making itself indispensable for finding information online.

Ethics and Politics

Ethical clearinghouses operate more subtly but no less powerfully. The World Health Organisation mediates between national health systems and global health standards, defining what counts as disease, what constitutes evidence, what policies are reasonable. Environmental, Social, and Governance rating agencies mediate between companies' practices and investors' values, creating metrics that reshape corporate behaviour.

The pattern extends seamlessly into political organisation itself. Tony Blair's 'Third Way' represents the same structural logic applied to governance, but it's neither new nor unique. Leonard Woolf's concept of international government placed international organisations in the third party mediating position, later fused into the League of Nations through Alfred Zimmern's work. Lenin's New Economic Policy used identical logic: public and private economic activity mediated through the Communist Party, which determined what was politically acceptable. The IFDA's 'third system' operates through the same mechanism — state and market coordination filtered through institutions claiming to represent civil society.

In each case, rather than direct bilateral relations or pure hierarchical control, entities coordinate through mediating institutions that determine what is 'internationally acceptable', 'socially just', 'politically correct', or 'sustainable'. Whether the mediator is the League of Nations, the Communist Party, or NGOs, the mechanism remains identical: positioning themselves as necessary arbiters of higher values to gain veto power over all participants.

The Power to Refuse

In each case, the clearinghouse gains power not through force but through position. It becomes the necessary mediator, the node through which other nodes must connect. This creates what network theorists call 'structural power' — influence that comes not from resources but from relationships. More critically, it grants clearinghouses the ultimate power: the ability to simply refuse to clear transactions.

The Bank of England can freeze a bank. ICANN can delete a domain. Visa can refuse a payment. AWS can unplug a business. When all flows must pass through a single mediating point, that point can halt any activity by declining to process it.

This power extends beyond mere regulation to existential control. Once a system requires clearinghouse mediation, the clearinghouse holds veto power over all activity within that system. Participants must comply with its requirements not because of legal obligations but because non-compliance means functional extinction within the network.

Patterns of Capture

The transformation from network to hierarchy to clearinghouse to capture follows predictable patterns. First, a network emerges with distributed topology — no single node controls the flows. Then hierarchical organisation is layered on top to manage complexity and scale. Certain nodes become mediators, handling communication between levels. Finally, these mediating nodes acquire the power to shape the system itself, often in ways that benefit them rather than the system as a whole.

The internet provides the clearest example. ARPANET was designed as a distributed network where information could find multiple routes to its destination. The early internet maintained this topology — anyone could set up a server, create content, access information. But as the network scaled, hierarchical organisation became necessary. Internet Service Providers emerged to manage local connections. Search engines organised content. Social media platforms managed social connections.

These hierarchical structures initially solved real problems of scale and complexity. But they also created chokepoints. A few companies began mediating most internet traffic. Google became the primary gateway to information. Facebook became the primary platform for social connection. Amazon became the primary infrastructure for cloud computing. The distributed topology remained technically intact, but practically, most traffic flowed through a handful of nodes.

This concentration of mediating power enabled new forms of capture. Platforms could prioritise their own content over competitors'. Search engines and social media platforms could manipulate what information people found. Cloud providers could terminate services for political reasons. The technical capability for distributed communication remained, but the practical reality became increasingly centralised.

Case Studies: Money and Digital Identity

The evolution of money provides another compelling example. Cash represents pure network topology — peer-to-peer value transfer without intermediaries. When you pay with cash, no bank records the transaction, no payment processor takes a fee, no government monitors the exchange. The network of users maintains trust through distributed verification of authenticity.

Central bank digital currencies represent the opposite extreme. CBDCs maintain the appearance of digital cash while implementing hierarchical control at every level. Every transaction requires permission from the central bank. Every payment can be monitored, blocked, or reversed. Programmable money can enforce spending restrictions, expire if unused, or redistribute value according to social credit scores.

The transformation follows the familiar pattern. Cash networks emerged organically from the need for portable value. Central banks became mediators, initially just providing stability and preventing counterfeiting. But this mediating position gradually expanded into comprehensive control over monetary policy, credit creation, and economic surveillance.

CBDCs represent the completion of this transformation — pure network topology replaced by pure hierarchical control. Digital identity systems provide the technical mechanism for this capture. Instead of anonymous cash transactions between peers, digital IDs ensure every individual exists as a traceable, controllable node within the hierarchy. Each person becomes permanently bound to their position in the system, unable to transact outside the mediating infrastructure. The combination of CBDCs and digital IDs eliminates the possibility of peer-to-peer value transfer — every transaction must flow through hierarchical control points that can monitor, restrict, or reverse payments based on identity verification.

Today's cryptocurrency movement demonstrates how subsidiarity rhetoric can mask hierarchical control. The principle of 'decentralisation to the lowest appropriate extent' sounds like distributed power, but who determines what extent is 'appropriate'? In practice, protocol developers decide what users can do through smart contract code. Validator networks decide which transactions to process. Governance token holders vote on changes that affect all users. Infrastructure providers can cut off access entirely.

Each level claims to delegate maximum autonomy to the level below while retaining only necessary coordination functions. But the higher levels always reserve the right to redefine those boundaries. Smart contracts appear to eliminate human intermediaries but actually embed developer decisions into unchangeable code. Decentralised Autonomous Organisations appear to distribute governance but concentrate voting power in proportion to token holdings. The technical capability for peer-to-peer interaction exists, but practical usage flows through hierarchical structures that can override lower-level decisions whenever deemed necessary.

Genealogy: The Deep Roots of Systems Thinking

These patterns of organisation and capture didn't emerge from nowhere. They reflect deep currents in how humans understand complex systems, currents that can be traced back over a century.

Alexander Bogdanov, a Marxist revolutionary who co-founded the Bolshevik party with Lenin in 1903, developed 'Tektology' in the early 1900s — one of the first systematic attempt at a universal science of organisation. Earlier monist thinkers influenced this trajectory, but Bogdanov is where the modern line begins. For Bogdanov, all phenomena could be understood as different forms of organisational activity. Whether examining cells, societies, or ideas, the same organisational principles applied: systems maintained themselves through dynamic equilibrium between organising and disorganising forces.

Crucially, Bogdanov recognised that Marx was wrong about who constituted the ruling elite. It wasn't those who owned the means of production but those who occupied mediating positions — the administrators, the technical experts, the committees that coordinated between different parts of the system. These administrators wielded power not through ownership but through their indispensable role in maintaining organisational coherence. They became the expert panels that rule contemporary society with impunity, making decisions that shape entire systems while claiming merely to provide neutral technical coordination.

Bogdanov's insights were largely ignored in the West, but they influenced Soviet planning and eventually reached Bertalanffy through indirect channels. Bertalanffy transformed Bogdanov's universal organisational science into General Systems Theory, emphasising open systems, environmental exchange, and self-regulation. Where Bogdanov saw struggle between opposing forces, Bertalanffy saw harmonious adaptation to environmental conditions.

Boulding inherited Bertalanffy's framework but added the crucial insight about levels of organisation. His 'Skeleton of Science' showed how systems theory could encompass everything from physics to psychology without reducing higher levels to lower ones. Each level of organisation had its own valid principles while remaining grounded in the levels below.

This genealogy reveals that systems thinking emerged from attempts to understand organisation itself, not just particular types of systems. The tension between network topology and hierarchical organisation reflects deeper questions about how complex systems can maintain coherence while preserving adaptability, how they can achieve coordination without sacrificing autonomy.

The Present Struggle

Understanding this genealogy illuminates present struggles over internet freedom, financial autonomy, and democratic governance. These aren't merely political or economic conflicts but expressions of the fundamental tension between distributed networks and layered control, between peer-to-peer interaction and mediated relationships.

The question isn't whether networks or hierarchies are better — both are necessary. Networks provide adaptability, innovation, and robustness through distribution. Hierarchies provide coordination, efficiency, and scale through organisation. The crucial question is whether hierarchy serves the network or captures it, whether mediating institutions facilitate flows or control them.

Conclusion: The Choice We Face

The tension between Bertalanffy's networks and Boulding's hierarchies isn't an abstract theoretical debate. Cash or CBDCs? ARPANET or platforms? Distribution or domination? These aren't technical questions but civilizational ones.

Every system we design embodies this choice: do we organise for adaptability or control? Do we distribute power or concentrate it? Do we enable peer-to-peer interaction or force everything through mediating institutions?

Networks alone become chaotic; hierarchies alone become tyrannical. The art lies in combining them properly — hierarchies that serve networks, mediators that facilitate rather than capture, clearinghouses that coordinate rather than control.

Understanding how systems theory explains control is the first step toward designing systems that serve human interest rather than human submission. In that choice lies the future of human organisation itself.

'Networks provide adaptability, innovation, and robustness through distribution. Hierarchies provide coordination, efficiency, and scale through organisation.'

I'm on the fence with this esc. Forest systems which had stability for aeons did not really have hierarchy in this sense. The mutual exchanges between organisms created the efficiencies and expanded scale as a result.

I still see the current predator (mediating) class/group as 'nature' or a part of nature because they see system exploits as food just like any other energy/resource harvesting unit. They are a forest fire. Consuming stored energy very quickly. Our task as I see it is to bring as many minds awareness of the situation so they can survive as seeds to resprout after the orgy of consumption.

I dunno. It's all very perplexing but I'm excited to follow your line of thought to see where you take me.

There is really much of interest in your writings, but I am afraid that you underestimate "the system": it's not rational, but criminal. Marx was wrong, but Bogdanov too: its not industrial capitalist, resp. administrators etc, its the criminal 500 year old project by financial capitalist organized by a few dynastic families, to own and exploit the planet as their Farm Earth. For the burden of proof see my book and articles.

Regards, Mees Baaijen - https://thepredatorsversusthepeople.substack.com/