It is noteworthy that Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s A Thousand Days1, written shortly after Kennedy’s assassination, strikes an oddly detached tone: a somewhat awkward blend of admiration and quiet relief. Kennedy is portrayed as a romantic idealist — visionary, but somewhat ill-suited for the managerial era then coming into view — with McNamara bringing every trick of the RAND Corporation’s Delphi Method2 in order to make this a possibility, guided by targets and ‘expert’ stakeholders.

This is a continuation of yesterday’s substack post.

That tone becomes more significant when viewed alongside Schlesinger’s role in negotiating the proposed World Congress for Freedom and Democracy. The initiative’s core material, notably, was authored by CIA agent Dana Durand, suggesting that beneath the surface lay ambition of a different kind.

Yet none of this on its own implies that Kennedy was a revolutionary or that Johnson was a conspirator. Rather, the record shows an inflection point in history — one through which Kennedy increasingly challenged the developing premise of managerial information systems, and Johnson, who accelerated and institutionalised said throughout government before McNamara jumped ship, across to the World Bank where he repeated the process globally. A process he, himself, had begun at the Department of Defense in 1961.

This can be further observed through the rising role of public-private planning, the increased use of tripartite governance (state, private sector, civil society), and the UN inclusion of NGOs through UN ECOSOC Resolution 1296 in 19683. These developments all align with aspects of the failed World Congress concept proposed in 1961 — but now dispersed across an international order, with the New International Economic Order4 introduced in 1974 together with IFDA’s Third System implementing these into policy through G77 nations dependent upon aid — while McNamara’s World Bank, UNIDO and UNDP busily introducing this same PPBS technology across especially third world nations, before Agenda 21 in 1992 broadened its emphasis to the entire world.

The inflection point can even be observed through earlier material, such as the 1961 Schlesinger CIA restructuring memo5, outlining a future form taken through a long-term strategic planning and research division, divisions in charge of administrative affairs and planning — a restructuring which would have landed Robert Amory, Jr. a role as the head of the division creating long-term outcome scenario analysis through computational modelling, with the State Department ultimately responsible for administrative approval of CIA missions following NSDM 406, incidentally the first revision of the original 54/12 which would impose external approvals upon the7 CIA8 itself9, with its successor — the OAG — was established in 197610.

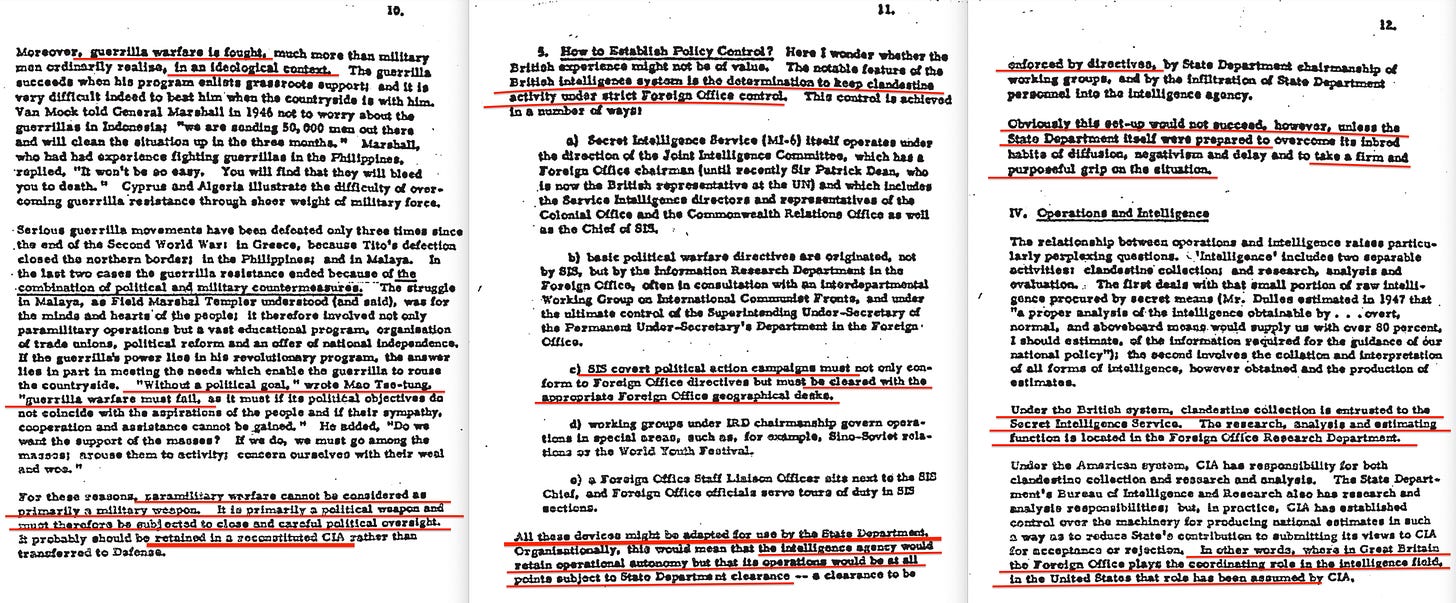

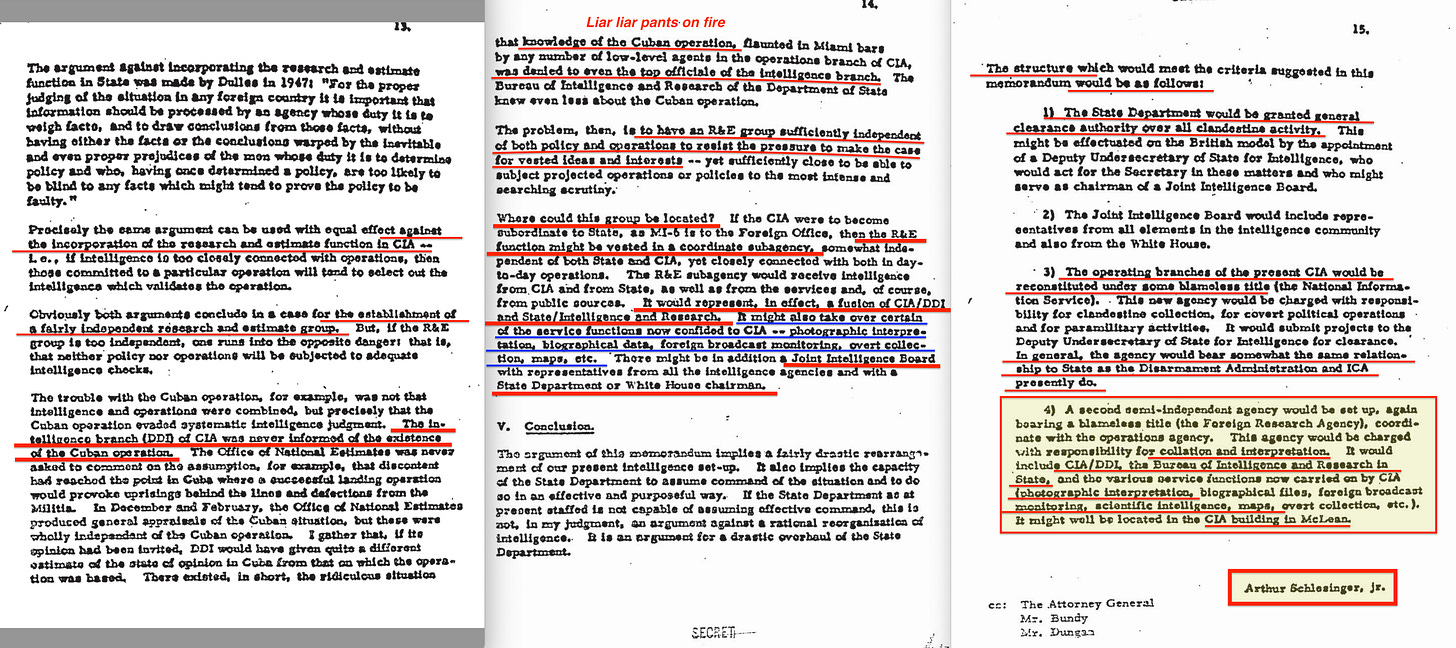

Schlesinger’s memo begins by him pressing his case for the reorganisation of the CIA. Though its record supposedly is good, the three issues outlined all trace back to its autonomy and operational freedom, from even the reach of the State Department.

However, these are not the days of yore, and while Schlesinger interestingly commends Allan Dulles for giving his people ‘remarkable protection’ from McCarthyism (who, incidentally and perhaps tellingly, was right11), the issue finally comes down to the progressive development of the CIA, which has led to it becoming a ‘state within a state’, answering ultimately to no-one but itself.

However, with communism being ‘a creed nurtured in conspiracy’ (you don’t say, Schlesinger!), the situation calls for a shackling of this independence. While secret activities are permissible (within reason), covert political operations are of somewhat more tricky nature, with paramilitary operations creating an even harder case to defend. On net balance, these cases should only be carried out when ‘the gains really seem to outweigh the advantages’, a proposition which naturally leads to a cushy job created for someone to administratively approve operations.

In fact, CIA operations have not been held effectively subordinate to US foreign policy, with clandestine intelligence gathering further outlined as something which should require approval from not just the Department of State, but also the local ambassador.

While covert operations technically require approval, this has been reduced to a mere rubber-stamping formality, leading to the malaise — while agents in DC are supposedly of top quality (but then, Schlesinger worked in DC himself), its field agents are of a somewhat more ‘rough’ and thus more unreliable character, evidenced through the failure in Cuba.

However, while the State Department in its present context can refuse requests, this is inadequate in implementation, thus calling for this reorganisation. Paramilitary operations, further, should possibly be part of the Department of Defense as opposed to the CIA, per Schlesinger — if for no other reason than:

… the moral and political price of direct paramilitary failure is acute for us…

Yes, Schlesinger even issues the ever-predictable moral call. And this is an issue, because though the CIA will be blamed for all sorts of things, communists ‘have no scruples about liquidating a losing show’.

Yet, we’ve hardly arrived on the next pages before Schlesinger suggests that paramilitary operations can stay with the CIA, provided it’s within the ‘reconstituted’ form he suggests — a form drawing upon the British model, where clandestine activity is retained within Foreign Office control, with formal administrative approval required from above; in the CIA’s case, leaving it with operational freedom but requiring administrative approval from the State Department.

The British model further outlines that responsibility for clandestine intelligence approvals resides with the Foreign Office — while the State Department has no say at all over similar matters in the United States.

That leaves research and strategic planning, however. And this issue should be resolved through the creation of a new unit, before Schlesinger goes on a mission to lie about Amory’s DD/I not being involved in — or having knowledge of — the Bay of Pigs, a claim that was utterly shot down in the previous post on The Fourth Casualty.

Ergo, this all calls for an independent division: a fusion of DD/I with State/Intelligence and Research — a Joint Intelligence Board, with a White House or State Department chairman.

The new structure would thus grant the CIA its operational independence, but require State Department administrative approval of clandestine activity, while:

A second semi-independent agency would be set up, again bearing a blameless title (the Foreign Research Agency) coordinate with the operations agency. This agency would be charged with responsibility for collation and interpretation. It would include CIA/DDI, the Bureau of Intelligence and Research in State* and the various service functions now carried on by CIA (photographic interpretation, biographical files, foreign broadcast monitoring, scientific intelligence, maps, overt collection etc. ) it might well be located in the CIA building in McLean.

…a third agency would be created, placed in charge of intelligence gathering and interpretation — again, while the State Department administratively approves clandestine activities, and the CIA itself retains operational freedom.

To repeat — because this is important — we have strategic planning and research in a new department, we have administrative approvals with the State Department, while the CIA retains its operational freedom. Incidentally, a new model which aligns with that used in Britain, where the Foreign Office is strategically placed.

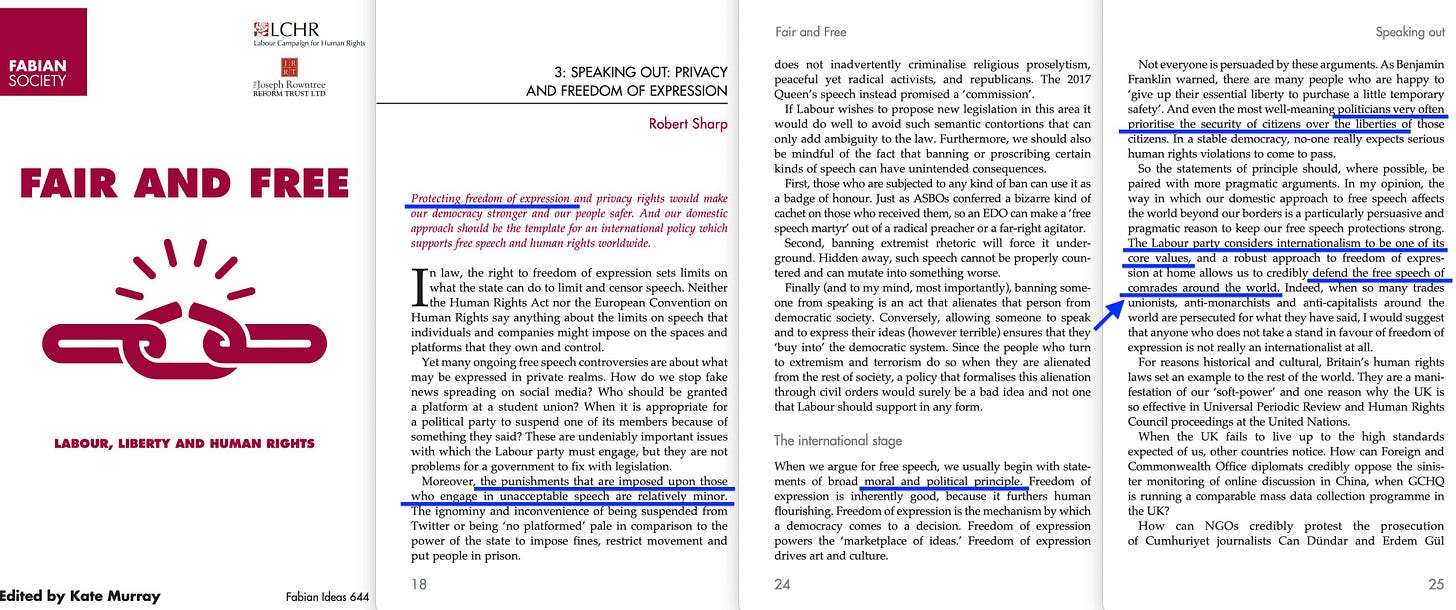

Because, by extraordinary coincidence, this tripartite reorganisation happens to align with the structure envisioned by the likes of Lionel Curtis12 and Alfred Zimmern13, who proposed that the British Empire should be replaced by a ‘third empire’ iteration in the form of the commonwealth Lionel Curtis promoted in 1918 — governed through economic cooperation of the sort Leonard S. Woolf through ‘International Government’ recommended in 1916, where ‘experts’ will judge what constitutes ‘international social justice’; principles which Zimmern helped institutionalise via the League of Nations in 1919, and which the Royal Institute of International Affairs progressively developed in the decades that followed — in particular, visible through their early work on monetary policy, enabling Keynes’s General Theory. In parallel, the Fabian Society produced the administrative frameworks for this model, while the Labour Party implemented these into UK policy.

What is this problem of the international struggle between the haves and the have-nots? The relationship between rich states and poor states simply reproduces on a larger scale the familiar problem between rich men and poor men, or a rich class and a poor class, within a single political community. And the broad solution is along the same lines. Just as we need social justice inside the community, so we need international social justice between the different states, rich and poor, of which the world is composed... The problem before us then is to work out in the relations between states a regime based on justice...

Oh, and did I mention that Zimmern and Curtis co-founded the RIIA?

This strategy even closely aligns with more contemporary developments, as it happens, with the Fabian Society in 1992 publishing Euro-Monetarism14, a pamphlet written by Ed Balls1516, leading to the Bank of England being granted its independence once the Blair-led Fabian government came to power in 1997.

Blair’s 1994 ‘Socialism’ pamphlet further suggests using stakeholder tripartite democratic principles, while his 1998 The Third Way pushed this into policy, while also recommending a structure relating to environmental protection which slotted right in with the 1992 UNCTAD Combating Global Warming recommendations, previously developed by the RIIA in the late 1980s.

And in that same year (1998), the Fabian Society issued recommendations relating to the reorganisation of the House of Lords, enacted to clear the road for the 2003 Fabian pamphlet, Future of the Monarchy, which issued a list of recommendations that were gradually translated into policy, stripping the monarchy of its few remaining powers — leading the British monarchy to a role serving as a pet mascot, per the intentions of the RIIA.

In an even more contemporary vein, recent announcements relating to the restructuring of the NHS17 more generally along the lines of prevention as opposed to cure aligns with the direction set forth by the 1918 People’s Ministry of Health declaration in the Soviet Union18, and much later, the 1978 Declaration of Alma-Ata. And this, too, unsurprisingly was first laid out in a pamphlet published by the Fabian Society19. And the RIIA has as of late begun to place a significant emphasis on Universal Health Coverage2021, even inclusive of dedicated forums2223, which in effect all lead to control of healthcare provision through a global stakeholder hierarchy, with emphasis on ‘subsidiarity’ and ‘cosmopolitanism’. It is, in other words, yet another piece of the puzzle, slotting right into its predestined place, culminating with the WHO passing that ghastly treaty only yesterday24.

Incidentally, did you know that virtually all senior comrades25 of the present Starmer-led UK government are members of the Fabian Society, a fact which through random choice would appear statistically impossible?

Returning to JFK — in retrospect, the 1963 inflection point can be considered the beginning of the global system moving from Cold War hostility towards managed internationalism, forward predicted by systems analysis and increasingly carried into action through mutual policy setting — especially following the 23 May 1972 agreement on environmental cooperation. Though it became increasingly obvious, this shift wasn’t yet the global governance of the 1990s and 2000s — but it created its intellectual and administrative foundation. Post-founding of the IIASA, this trajectory accelerated massively, in spite of — or perhaps especially because — Moiseev concluded that future prediction of complex systems such as climate was a fool’s errand.

Kennedy — however flawed he may have otherwise been — appears to have been the one president perhaps not sharply opposing this trajectory, but certainly beginning to perceive its outline and progressive implementation. And while that might place the RAND Corporation’s ideology-driven military-industrial complex as a prime suspect, the reality once again points back to the emphasis on economics — which Zimmern had outlined as the proper focus for restructuring the British Empire, and which McNamara used as a core justification for its implementation within the Department of Defense in 1961.

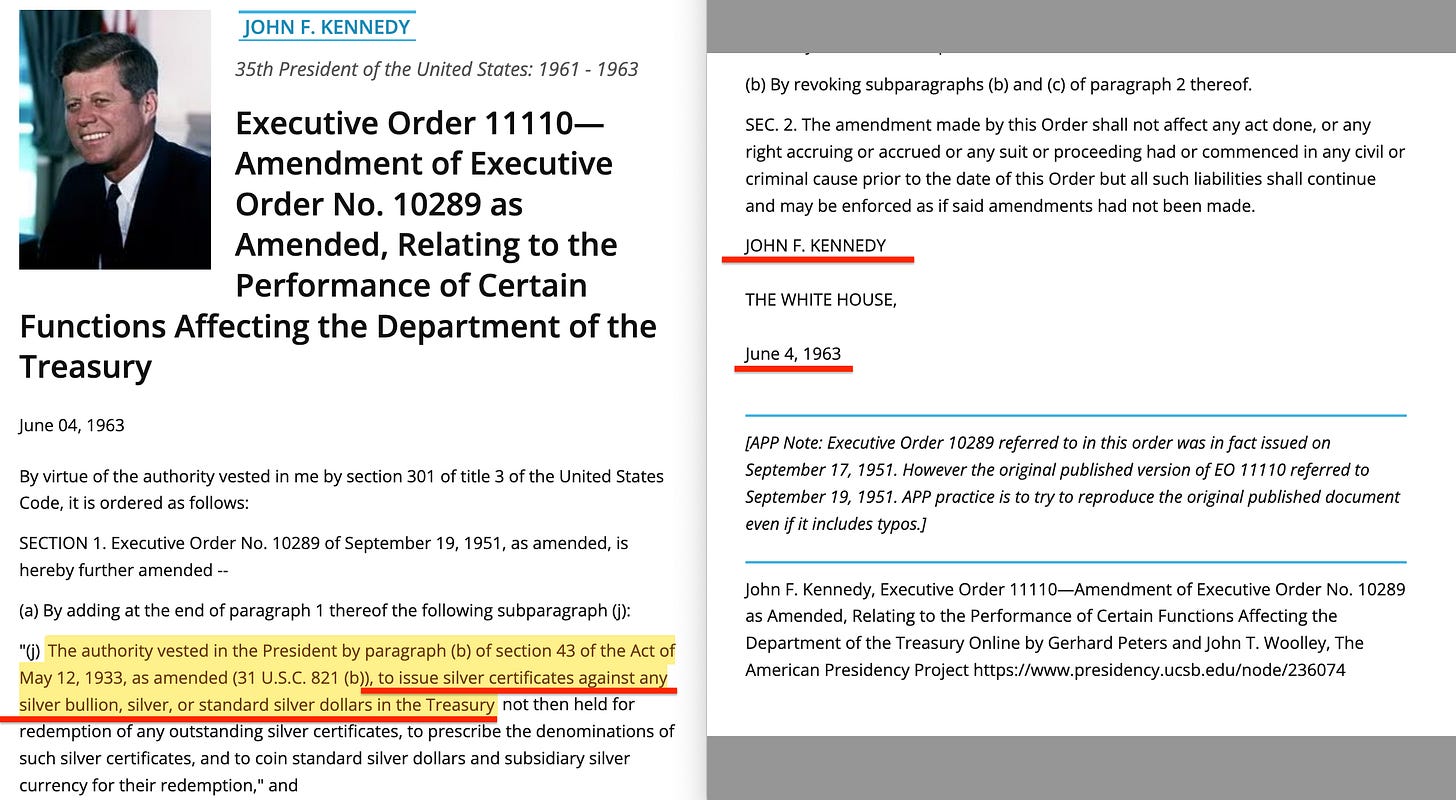

But further — due to Silent Weapons for Quiet Wars, and hence the Federal Reserve — only those executive orders issued by the LBJ administration almost as soon as the Vietnam War erupted could realistically have enabled this flow of information. The breakout of the Vietnam War would have presented a perfect opportunity to hide the EOs, with few truly independent journalists showing signs of investigating. Couple these with Kennedy’s Executive Order 1111026, and perhaps — just perhaps — the military-industrial complex at least had a cooperative partner. But while the military-industrial complex itself is a very visible potential, EO 11110 on its own is not strong enough to carry the argument of the complicity of the central banks.

But there’s yet another argument — and it’s yet another rarely explored one. When Arthur Schlesinger Jr. fought, unsuccessfully, to prevent the dismissal of Robert Amory Jr. after the Bay of Pigs, he wasn’t merely defending a man but a vision. Under Schlesinger’s suggested tripartite division of the CIA27, Amory would most likely have overseen parts of the pivotal third — the strategic division, tasked with producing scenario analysis from surveillance satellite data. Schlesinger’s ‘research’, for lack of a better word.

Then fast forward to 25 August 1965: LBJ formally institutes PPBS across all federal agencies, triggering a cascade of executive orders and legislative initiatives — not just in defence, but also in environmental policy, public health, and fiscal surveillance of major banks via reporting mechanisms tied to the Federal Reserve.

However, only four days prior — on 21 August 1965 — Ray Cline, Amory’s successor, proposes the creation of a new intelligence body: COMIREX2829303132 (the Committee on Imagery Requirements and Exploitation), a project utterly aligned with Schlesinger’s vision. COMIREX would be responsible for managing photographic intelligence and long-range analysis — precisely the kind of anticipatory function Amory was building. And where was this new systems-based unit placed?

Under the CIA’s Deputy Director for Intelligence — the very role from which Amory had been removed.

And as is always the case with these, once you know for what to search, there’s no shortage of material — in this case relating to COMIREX33343536373839. This stream begins immediately after PPBS came into being, yet the related planning began a few years prior, with one 1963 CIA memo showing up detailing a related working group. The planning, in short, began prior to what would have been Amory’s division had even been established. They knew where they were going, in other words.

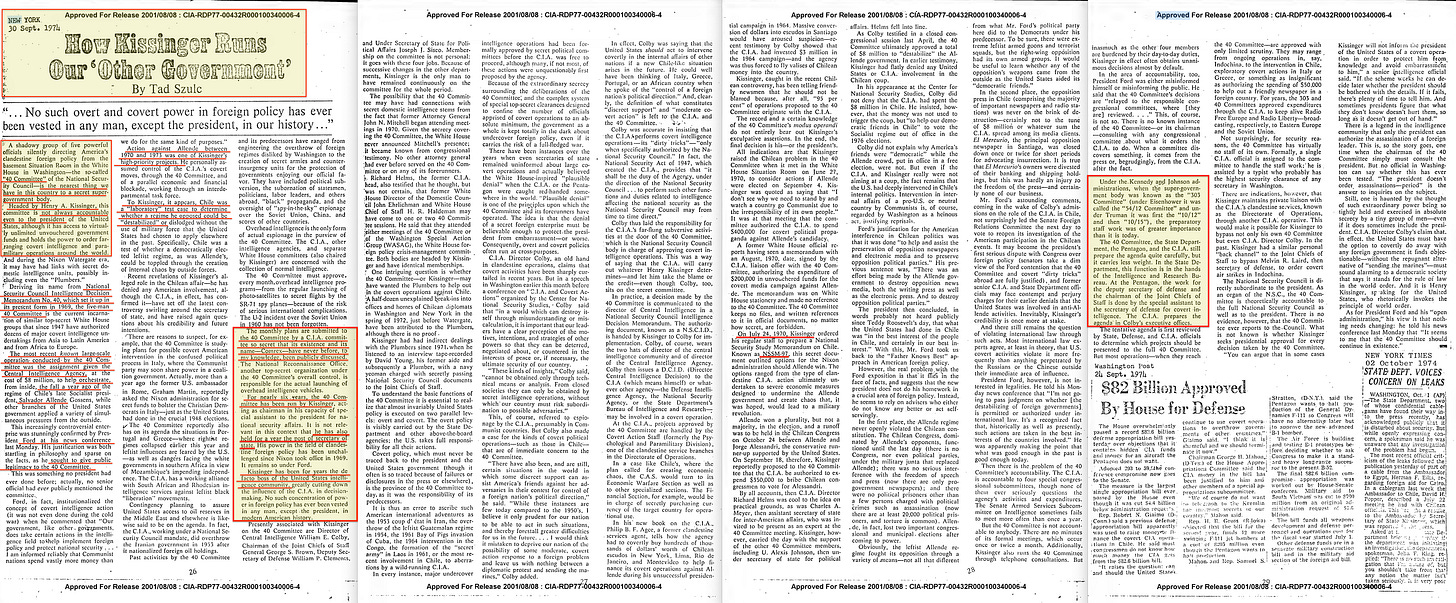

Schlesinger’s second stage — the administrative approvals — would come through the Kissinger-led Committee of 40, per yet another unclassified CIA memo40:

As the only newsman around who has been a member of the Forty Committee, that small offshoot of the National Security Council which approves and oversees U.S. clandestine activities abroad, it may help if I give you a re port on just what goes on -~ and how the issues of morality sometimes conflict.

This entire document offers a very interesting insight into Kissinger’s related role, which we, for the sake of brevity, will have to skip:

The revelations were potentially damaging to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, who chaired the so-called Forty Committee that approved the covert CIA operations, as well as to former Ambassador to Santiago Edward M. Korry and former Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs Charles A. Meyer. These and other Kissinger deputies have testified in congressional hearings that the US. did not interfere at any time in Chilean life.

Not only was Kissinger in charge of the State Department, but he also chaired the Forty Committee, granting administrative approval of CIA ops.

And Kissinger really was the beating heart of this clandestine activity:

The monthly plans are submitted to the 40 Committee by a C.I.A. committee so secret that ‘its existence and its name—Comrex—have never before, to my knowledge, been publicly discussed. The National Reconnaissance Office, another top-secret organization under the 40 Committee’s overall control, is responsible for the actual launching of overhead intelligence vehicles. ’ For nearly six -years, the 40- Committee has been run by Kissinger, acting as chairman in his capacity of special assistant to the president for national security affairs. It is not relevant in this context that he has also held for a year the post of secretary of. state. His power in the field of clandestine foreign-policy has been unchallenged since Nixon took office in 1969. It remains so under Ford. Kissinger has been for years the de facto boss of the United States intelligence community, greatly cutting down the influence of the C.1.A. in decisionmaking. No such concentration of power in foreign policy has ever been vested in any man, except.the president, in modern American history.

The only issue was — these two operations were, for all intents and purposes, separate.

But — though slightly off-topic — of further interest is the CIA’s involvement in the election of Salvador Allende in Chile. The CIA, in short, attempted to manipulate the outcome and eventually helped cut off Chile’s access to bond markets — a strategy Allende described as an ‘invisible blockade’. But this raises a question: apart from the stated alignment with socialist principles, why did Allende’s government have to be removed — especially at a time when the United States and the USSR had begun cooperating, most notably in the area of so-called environmental protection through the global modelling agency IIASA?

Well, a reason could be this: in the early days of his administration, Allende brought in Stafford Beer41 to implement the Viable System Model42 under the banner of Project Cybersyn43 — a form of real-time, adaptive governance rooted in feedback, decentralisation, and cybernetic logic. In many ways, it resembled the very systems the US and USSR were beginning to promote globally.

So why was it intolerable?

Because Cybersyn44 wasn’t under the control of either bloc. It represented a third path — a sovereign cybernetic system operating outside the framework cemented by the May 23, 1972 US–USSR agreement and soon institutionalised via IIASA.

Much like today’s geopolitical struggle over AI ethics and standards, the 1970s were marked by a quiet competition for control over the emerging cybernetic order. A competing system, launched by a nation like Chile, posed a threat — not ideologically, but structurally. It demonstrated the possibility of feedback-based governance outside supranational control.

Consequently, by destabilising Chile through cutting off their access to bond markets, the United States eliminated a rival cybernetic architecture and reinforced the message that integration into the emerging global system — structured through institutions like IIASA — was non-negotiable. And the man who orchestrated that destabilisation was Henry Kissinger, whose deep ties to both the Council on Foreign Relations45 and the Rockefeller family46 are well documented.

With Allende gone, Pinochet seized power and invited the so-called Chicago Boys47 — US-trained economists — to restructure Chile’s economy. Their prescriptions bore striking resemblance to the recommendations outlined by Leonard S. Woolf in his 1916 report, International Government — a vision that, in contemporary terms, laid the groundwork for neoliberal trade policy. Woolf’s framework proposed the gradual erosion of national borders, replaced by international institutions operating beyond the reach of democratic accountability.

A model, incidentally fused into the architecture of the League of Nations — and eventually its postwar successor, the United Nations.

Yet, that still leaves a question: with the CIA in charge of operations, the Kissinger-led Forty Commission in charge of administrative approvals, and the DD/I in charge of research gathering and analysis — who would be in charge of setting overall strategy and thus, perform long-term planning?

To be continued.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The price of freedom is eternal vigilance. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.