If you had told me only a few years ago that JFK’s assassination led to contemporary global governance, I would’ve thought you were crazy.

But I suppose that’s half the battle — because it’s not as far-fetched as it first seems.

Let’s begin with a recap.

John F. Kennedy’s administration marked the last serious resistance to the institutionalisation of technocratic governance. McNamara introduced the Planning-Programming-Budgeting System (PPBS) at the Pentagon in 1961, but Kennedy quickly grew sceptical of its computational logic — especially after the Cuban Missile Crisis exposed the risks of rigid modelling in nuclear scenarios. He halted its expansion beyond defense while firing the top brass of the CIA who deliberated its implementation. This throttled Schlesinger’s ambitions, arresting the development of the socialist ‘democratic international’ initiative, the ‘World Congress for Freedom and Democracy’, supported by the dismissed CIA director of intelligence, Robert Amory, Jr.

Following the assassination of JFK, Schlesinger’s 1961 blueprint to restructure the CIA along British lines progressively came into being — separating operations, administration, and research. Ray Cline replaced Amory to become chief of the latter division, while Kissinger’s later position on the Forty Committee saw him granted control of administrative approval of CIA’s operational mandate. Schlesinger’s 1961 vision thus converged with McNamara’s PPBS through the formation of Ray Cline’s research division, but the tripartite structure in fact not only aligned with that of British intelligence itself, but also the reorganised British Empire early in the 20th century by Alfred Zimmern and Lionel Curtis, who in effect outsourced research to the RIIA, administration to the Fabian Society, while the UK government itself became the operational executor.

Meanwhile, the quasi-fusion of the CIA and the Council on Foreign Relations became a covert institutional engine behind this transition. Schlesinger’s World Congress proposal — co-authored with CIA operative Dana Durand and backed by Robert Amory Jr. — served as a prototype for stakeholder rule masked as democratic renewal. The CFR, far from a passive think tank, became a central organising hub where long-term strategy was coordinated, intelligence flows were integrated, and covert governance was legitimised through ‘common good’ civil society organisations — moral imperatives fronting computational modelling simulations. The deployment of the managerial system Kennedy had begun to question accelerated under LBJ, with PPBS as its operational spine.

What remains is to show how this logic scaled from its bureaucratic origin in 1961 to its global integration — not least by McNamara, who by the end of the decade was in charge of the World Bank. PPBS, far from a mere budgeting tool, gradually became the programmable substrate for planetary governance — exported via UN agencies and embedded in various frameworks, including the Sustainable Development Goals. This final post traces that arc: how a military logistics system became the architecture of a cybernetic world order.

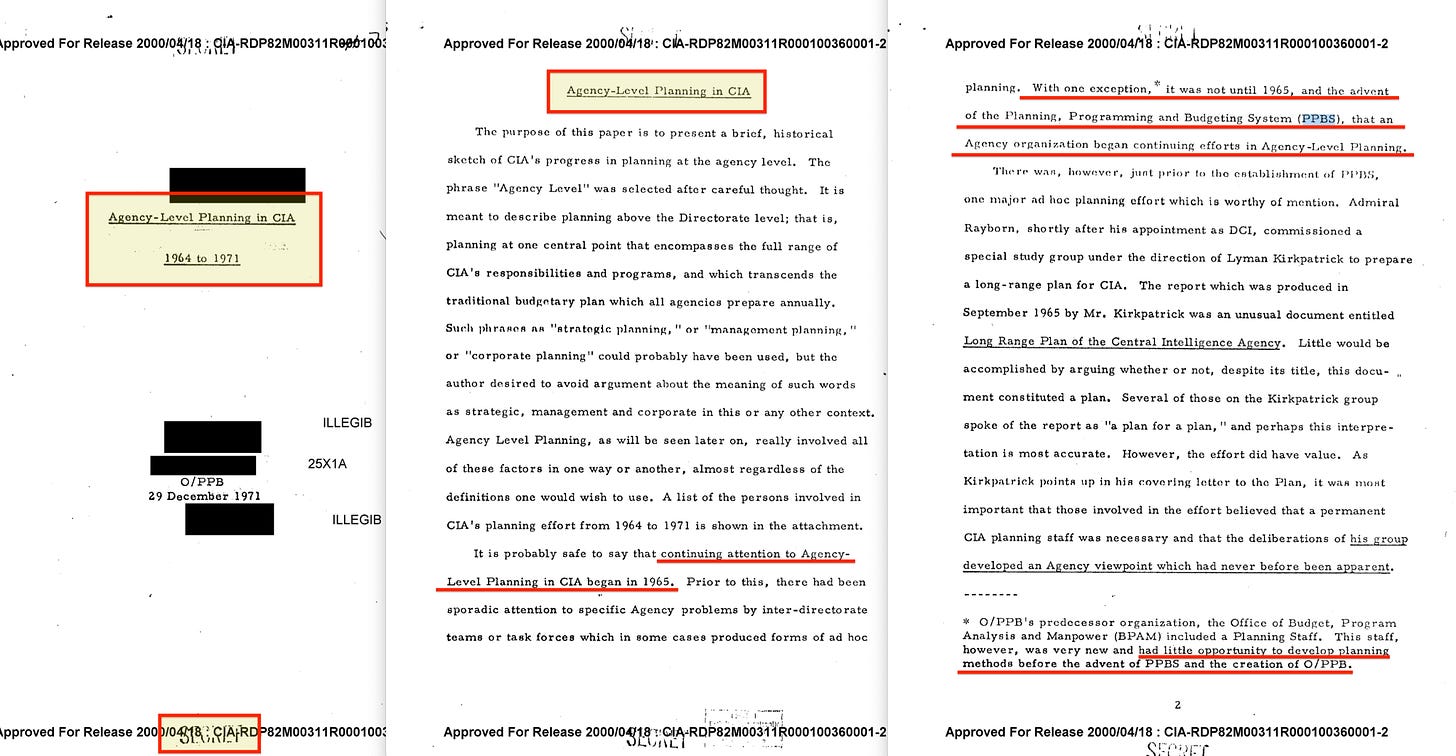

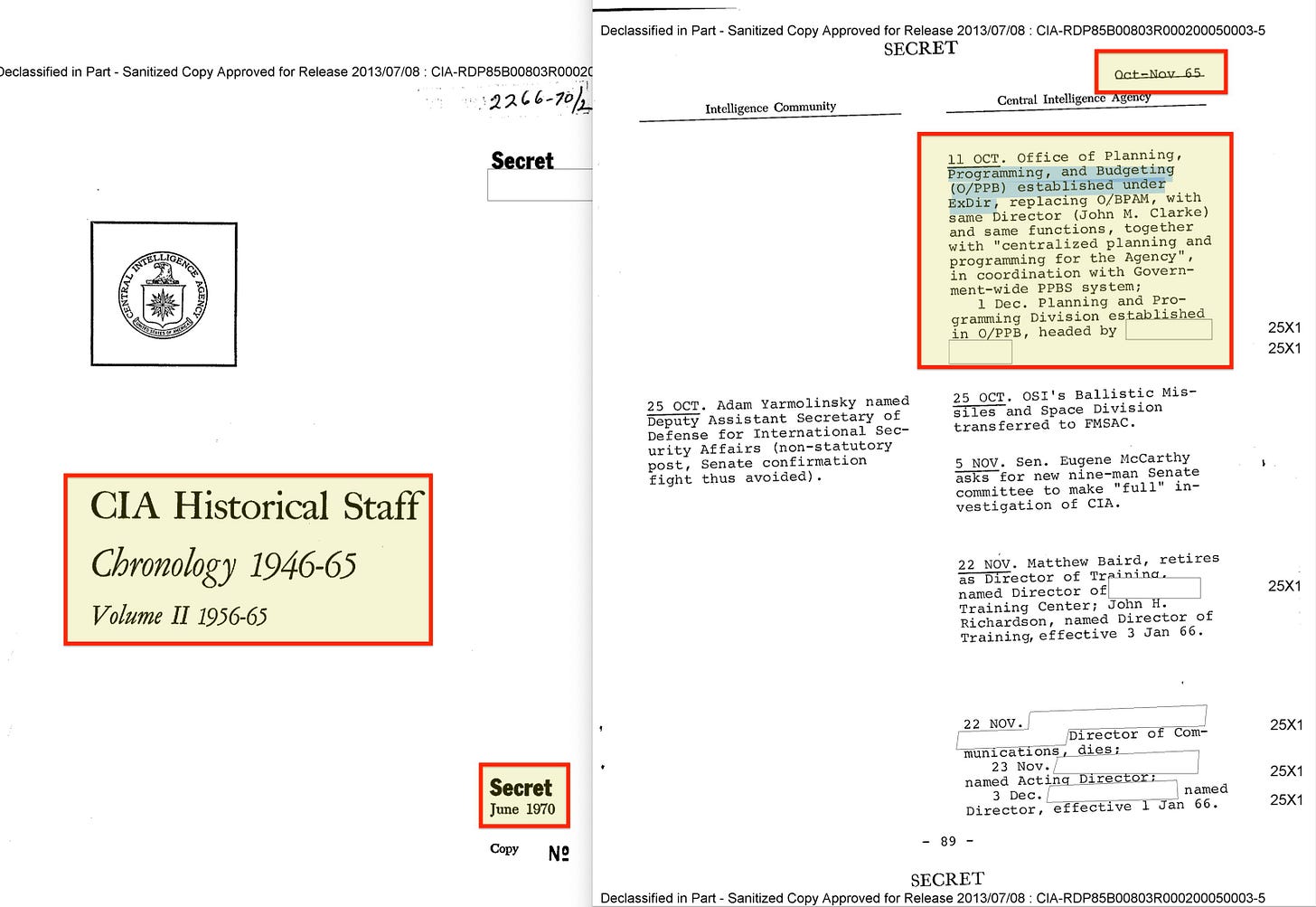

While techniques of systems analysis had circulated within the intelligence community in earlier years, the CIA’s own internal records are quite explicit: agency-level planning did not formally begin until 1965. According to a 1971 internal report titled Agency-Level Planning in CIA1, ‘continuing attention to Agency-Level Planning in CIA began in 1965’, thus marking a clear institutional shift. Prior to this efforts had been sporadic, seemingly lacking a coherent framework. The administrative break was codified with the October 1965 creation of the Office of Planning, Programming, and Budgeting (O/PPB)2, established under the Executive Director and aligned with the federal government’s broader PPBS mandate issued by LBJ. The CIA Historical Staff Chronology3 confirms this development, noting the establishment of centralised planning functions within O/PPB to bring intelligence operations under programmatic control. While earlier planning groups considered long-range analysis, 1965 remains the moment the Agency itself recognses as the beginning of systematic, agency-wide planning.

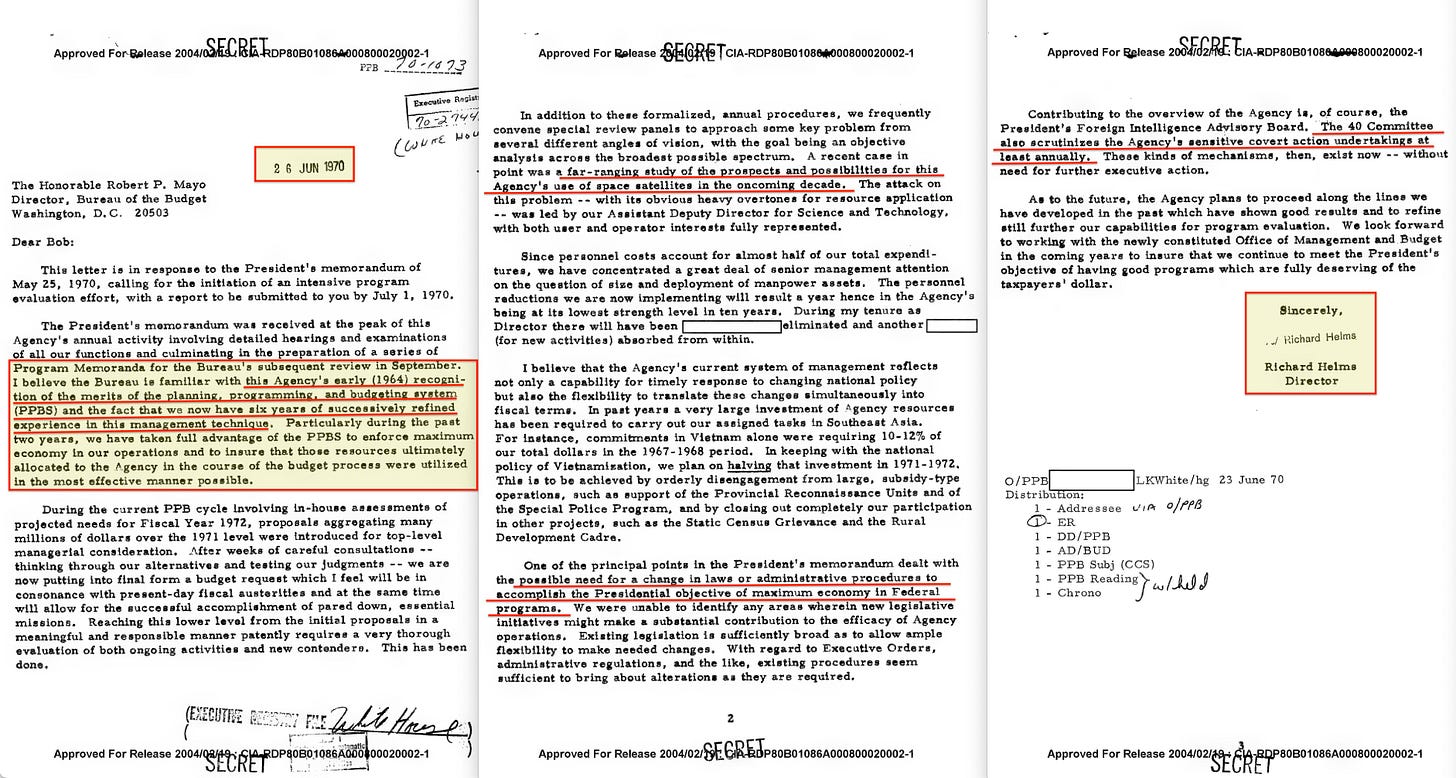

While the CIA’s formal adoption of agency-level planning structures did not begin until 1965, internal correspondence reveals that experimentation with the Planning-Programming-Budgeting System (PPBS) began in 19644. In a June 1970 letter to Bureau of the Budget Director Robert Mayo, CIA Director Richard Helms5 refers to ‘six years of successively refined experience in this management technique’, confirming that the Agency had quietly begun adapting PPBS methodology even before Johnson’s government-wide directive. Helms underscores how the system was used to maximize internal efficiency, reduce force levels, and reallocate resources with precision — pointing specifically to Vietnam drawdowns and satellite planning as key applications. These operations were organized around ‘Program Memoranda’ for interagency budget review, directly mirroring Department of Defense procedures.

Yet the origins of CIA involvement with Planning-Programming-Budgeting Systems (PPBS) in fact began years earlier. As Casting Net Assessment6 details, the McNamara revolution was born from a technocratic network rooted in RAND, Project Lamp, and Cold War systems analysis. This network sought to tame strategic uncertainty, reframing defense planning as system of inputs, outputs, and predictive simulation. The PPBS emerged as the operational logic of this worldview: a systems interface that aligned defense priorities with five-year economic forecasts, budgetary concerns, and measurable outputs. In March 1961, Hitch formally proposed converting nuclear defense budgeting into a unified, programmatic structure. McNamara immediately endorsed it, ordering its expansion across the entire Department of Defense. This was more than administrative reform — it was a metaphysical coup, with war no longer planned by generals using judgment and experience but programmed by economists and systems analysts without a shred of combined military experience. PPBS, in this frame, was not a neutral tool but the architecture of a new regime which facilitated the transfer of complex strategic decisions to those who had no legitimate experience with the matter at all.

This drive did not stay confined to the Pentagon. Before the CIA’s formal adoption of PPBS structures in 1965, internal experiments were already underway. Project Lamp — launched under the direction of Robert Amory in collaboration with Andrew Marshall, George Pugh, and Loftus — concluded in April 1961, almost simultaneously with McNamara’s PPBS rollout. The project evaluated whether systems analysis could be applied to long-range intelligence forecasting, using five-to-seven-year force structure projections to inform national posture planning. Though the CIA did not immediately implement its recommendations, Project Lamp marked one of the earliest institutional tests of applying programmatic logic to intelligence. As the report acknowledged, the objective was to create ‘an integrated, consumer-oriented program’ of national estimates — an early indicator that the Agency was already aligning with RAND’s managerial paradigm well before PPBS was implemented into practise. The transformation of intelligence into a controllable system was already underway, but Robert Amory, Jr’s prompt dismissal likely slowed its adoption, given JFK’s decision to have him wiretapped in February, 19637.

PPBS represented not just an administrative reform, but a deliberate restructuring of institutional power within the Department of Defense. Prior to its implementation, the military services retained broad autonomy over their own planning and budgeting processes. McNamara imposed a corporate-style model that subordinated military judgment to centralised civilian control, much to their chagrin8. At President Kennedy’s direction, the system was designed explicitly to assert tighter SECDEF authority over the services — replacing hierarchical discretion with programmatic logic. PPBS eliminated service-specific budget ceilings, forced proposals into long-term fiscal envelopes, and mandated justification through cost-benefit analysis. The military was not asked to adopt the system — it was compelled to in spite of continuous vociferous challenge. As the system matured, McNamara’s Office of Systems Analysis granted civilian 'whiz kids' the power to model, simulate, and adjudicate defense priorities according to economic rationales as opposed to operational judgment. Strategic decision-making was restructured, and the Pentagon itself increasingly became a control system — coordinated not by generals, but by government technocrats. By 1964, PPBS was fully entrenched at the DoD, setting the stage for its government-wide rollout under Johnson.

PPBS represented a new managerial architecture grounded in systems theory, cybernetics, and control. McNamara and Hitch deliberately fused economic modelling, systems analysis, and public administration into a structure that displaced political discretion and military judgment in favour of algorithmic optimisation. The goal was explicit: to make defence planning ‘a simple matter of costing out the good chosen’. Strategic aims were disaggregated into program elements, each evaluated by cost-benefit metrics, effectively stripping the military of discretionary authority over policy, procurement, and appropriations. This technocratic logic was so expansive that Johnson sought to extend it government-wide in 1966 via executive order, but the broader rollout stalled under Congressional resistance, who — for good reason, given the experiences of the DoD — feared the erosion of constitutional power. The contrast with Melvin Laird’s later reforms is telling. Appointed after McNamara, Laird attempted to reintroduce ‘participatory’ management by empowering the services and restoring input from the Joint Chiefs. He rejected the idea that the Secretary of Defense should dictate tactical specifications, but Laird did not dismantle PPBS. He merely softened its edge — permitting more bottom-up input while leaving its core logic intact, though still enabling ‘subsidiarity’ principle top-down overrides of decisions. PPBS reframed defence not as strategy, but as system governed by quantification, rationalised planning, and predictive control — increasingly dictated by systems analysts as opposed to the military itself.

The creation of PPBS was not merely a policy reform — it was a political reconfiguration of institutional power. President Kennedy explicitly distrusted military control over planning and budgeting and sought to place those functions under civilian authority9. McNamara, installed to execute this mandate, bypassed the service branches entirely. Yet, the shift was immediate and aggressive: budget categories based on service lines were eliminated, replaced with cross-cutting ‘program elements’, which through chaining enabled five-year projections that could be modularly aggregated or disaggregated for managerial analysis. Yet, these were not neutral tools — they granted civilian planners the capacity to reengineer defense priorities from above, using economic criteria rather than strategic deliberation. McNamara’s personal intervention to impose PPBS on the FY1963 budget — before formal review processes had stabilised — underscores the coercive nature of this transformation.

Though met with fierce resistance from figures like Admiral Arleigh Burke — who objected to the abstraction of program elements and the burdensome workload placed on service staffs — the 1961 implementation of PPBS initiated an irreversible structural realignment in defense governance. Within a few years, each branch had trained internal officers in PPBS methods, signaling a shift not toward restored autonomy but toward adaptation. The military was being operationally reprogrammed: taught to navigate and internalise civilian-imposed systems logic rather than assert traditional strategic discretion. While attempts at recalibration, such as Melvin Laird’s ‘participatory management’ model did allow for greater input from the Joint Chiefs and service secretaries, it not fundamentally displace the architecture McNamara had installed.

By 1962, the Planning-Programming-Budgeting System (PPBS) had already triggered deep institutional backlash within the military establishment10. Far from welcoming the shift, the services viewed PPBS as an alien imposition — an intrusive civilian framework designed to strip them of strategic autonomy. As documented in internal critiques, senior officers were openly hostile to the system, describing it as a ‘radical departure’ that subordinated military judgment to economic analysis and systems theory. The Air Force’s General White flatly rejected the new approach, while Army officers resented what they saw as an assault on professional discretion.

Central to this resentment was the growing power of McNamara’s Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), which seized control of force structure decisions through a rigid, top-down schedule of program reviews and budget cycles. The Joint Chiefs of Staff were effectively relegated to procedural compliance, forced to submit ‘blood statements’ — uneasy affirmations of sufficiency — rather than advocate openly for operational needs. Civilian analysts became the new arbiters of military planning. Their reliance on modelling, projections, and technocratic metrics was seen by service leaders as dangerously detached from combat realities. For the Army, which relied on adaptive, contingency-based planning, PPBS was particularly ill-suited — its rigid force packages and five-year fiscal plans clashed with the dynamic and unpredictable nature of ground warfare.

Ultimately, the Kennedy-era reforms institutionalised under Johnson were less of collaborative adjustments but deliberate encroachment: a civilian-led seizure of planning authority justified in the language of operational efficiency. What emerged was not merely a bureaucratic innovation but a structural realignment: a national security state governed not by command authority or operational judgment, but by program analysts, simulations, and logic imposed from above.

By late 1962, McNamara had institutionalised the Five-Year Defense Program (FYDP) as the official framework for all force and budget planning, cementing civilian supremacy over the military services. Though the FYDP nominally incorporated service inputs, military leaders like Curtis LeMay quickly recognized it as a facade. In practice, the real decisions were being made by analysts within McNamara’s Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), with the services reduced to procedural compliance. LeMay’s refusal to endorse the FYDP due to ‘serious deficiencies’ underscored this growing alienation. Program Change Proposals (PCPs) were routed through OSD, not initiated by the chiefs, effectively cutting them out of upstream influence. What remained was a tightly managed review process in which the services were expected to justify their needs using a language they did not write, within a structure they did not control, resulting in a force they didn’t request.

By 1964, this transformation was undeniable. As General Maxwell Taylor observed, the Joint Strategic Objectives Plan (JSOP) had become a retrospective exercise — used not to guide policy, but to rationalise decisions already made by civilians. Strategic assessments had been reduced to back-justifications for economised force levels derived from abstract models and ‘employment factors’. The JCS, once the intellectual and operational center of American war planning, found itself marginalised by a civilian technocracy openly boasting of its independence. McNamara himself stated that he and the President had agreed on 85 percent of defense items without JCS input. Meanwhile, civilian analysts within OSD routinely overruled or ignored service objections, applying statistical screens and cost-effectiveness criteria that bore little relation to battlefield contingencies. As the Vietnam War escalated, the White House was even warned that seeking JCS feedback might introduce friction into budgetary planning.

Admiral George Anderson’s frustrations with McNamara’s centralisation of authority progressively escalated. As Chief of Naval Operations, Anderson was one of the few service chiefs who openly challenged the civilian systems analysts whom he viewed as usurping operational roles that had traditionally belonged to experienced commanders. He bristled at the notion that individuals with no combat experience were now dictating carrier procurement levels, force compositions, and strategic doctrine through abstract models and cost-efficiency metrics. For Anderson, this shift was a violation of the constitutional logic of civil-military balance. He warned against ‘downgrading the role of the men who may have to fight our country’s battles’ and interpreted the rising influence of the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) as a direct assault on the statutory responsibilities of the Joint Chiefs.

The conflict came to a head during a procurement controversy, where Anderson opposed what he saw as an ideologically driven effort to impose joint-service hardware despite Navy objections. His refusal to endorse the program was treated by McNamara as insubordination, and Anderson was removed — reassigned as ambassador to Portugal in what many understood as political retaliation. The message was clear: resistance to the new order would not be tolerated. But Anderson’s removal did not resolve the deeper problem. What had once been a strategic conversation between commanders had become a simulation game played by civilians fluent in programming tools but alienated from the realities of warfare. For Anderson and others, this was not progress but inversion: a technocratic coup disguised as rational reform, hollowing out the institutional authority of the military from within.

By 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson had fully embraced and expanded the PPBS framework, issuing a memorandum directing all government departments, bureaus, and agencies to implement a programmed budgeting system11. Under Johnson, the emphasis on rigorous quantification, cost-benefit analysis, and programmatic control intensified, reinforcing the managerial logic that subordinated traditional discretion to computational evaluation. The Department of Defense’s Bureau of Budget Bulletin 66-312 codified PPBS as the official process, mandating explicit structuring of ends and means, and shifting budget decisions firmly toward data-driven analysis. This approach — though economically efficient — further entrenched a system where every dollar was accounted for as a ‘maximum benefit’ investment, measured by ‘dollar spent or per man day paid’. Johnson’s policies thus solidified PPBS as a central pillar of federal governance, extending the technocratic paradigm well beyond defense to shape the entire government’s budgeting culture.

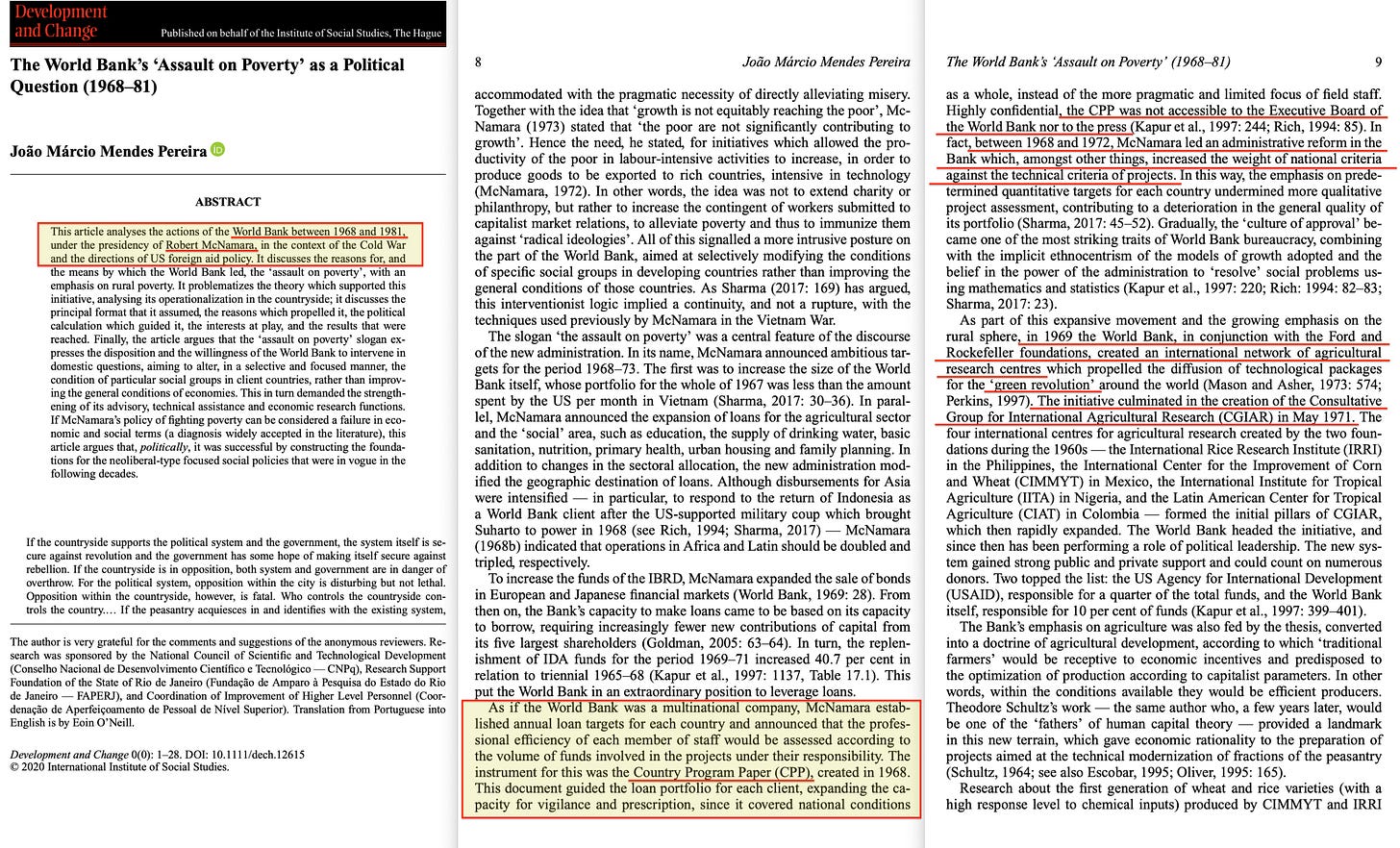

In April 1968, Robert McNamara took office as President of the World Bank. Within months, he implemented the Bank’s first five-year lending plan and established the Country Program Papers13 (CPPs), a mechanism designed to impose quantifiable, multi-year financial targets on borrower countries. The CPPs transformed World Bank operations by linking loan approvals and professional staff evaluations to strict cost-benefit criteria and national economic indicators, shifting decision-making away from qualitative development assessments toward rigid computational modelling frameworks. This reform effectively reprogrammed the World Bank as a managerial instrument, embedding surveillance and control into the administration of international aid and enforcing standardised economic rationality upon diverse political and social realities under the banner of international social justice.

This emerging planning logic was soon embraced within the United Nations system14. By the early 1970s, the United Nations Development Programme15 (UNDP) had adopted ‘medium-term programming’, introducing systematic multi-year planning aligned with ‘indicative planning figures’ to rationalise aid contributions. The 1973 General Assembly resolution 31/9316 mandated medium-term plans as essential tools for coordination across the UN’s diverse bodies. Subsequent Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) and General Assembly resolutions, especially in 1976, formalised these plans as the central instrument for programming, budgeting, and evaluation within the UN system. What began as a technocratic budgeting innovation for US defense progressively evolved into the blueprint for a global governance architecture, harmonising international development efforts around standardised, multi-year programmatic cycles.

The global spread of medium-term planning systems throughout the 1970s cannot be divorced from the ideological and institutional momentum generated by the New International Economic Order17 (NIEO). Officially launched by the Group of 77 at the 1974 UN General Assembly, the NIEO demanded a fundamental restructuring of global economic governance, allegedly to empower developing countries through greater control over natural resources, fairer trade terms, increased aid, and enhanced participation in international decision-making. Central to this vision was the call for sovereign planning capacity and coordination mechanisms. In response, institutions like the UNDP and the World Bank incorporated national planning frameworks directly into their operational mandates — but far from acting as neutral facilitators, they imposed structured multi-year plans and quantifiable objectives as conditions for access to finance and technical assistance. Under the influence of McNamara’s managerial reforms at the World Bank and the post-Johnson expansion of PPBS-style governance, these demands transformed supposedly self-directed development into a regime of technocratic control, where program budgeting, strategic indicators, and ‘rational allocation’ became the common language of international cooperation, where access to development finance required the implementation of McNamara’s technocratic system.

At the same time, the NIEO spurred efforts to rethink global governance itself beyond development programming. Institutions like the UN Institute for Development Planning (UNIDP) and the International Foundation for Development Alternatives (IFDA) advanced a ‘Third System’ model, aiming to blend public, private, and civil society actors into a supposedly decentralised, participatory framework. Supported by key G77 leaders and segments of the UN secretariat, this vision soon became the dominant planning paradigm. IFDA’s approach was integrated into system-wide coordination efforts, notably General Assembly resolution 337418 (XXX), which codified medium-term plans as binding instruments for inter-agency harmonisation. In effect, the agenda was co-opted into programme-based budgeting and technocratic metrics, reinforcing the planning regimes first forged in the Pentagon and expanded under McNamara that now governed international development at large.

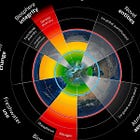

The convergence reached its apex with the 1987 Brundtland Report, Our Common Future, which reframed sustainable development as holistic systems theory — linking long-term planning, ecological boundaries, and economic coordination within a shared moral framework. The report softly called for trisectoral governance, expanding roles for NGOs, business, and scientific communities alongside states, with this vision materialising at the 1992 Rio Earth Summit with the adoption of Agenda 21, institutionalising these principles across the UN system. Drawing directly on decades of program budgeting, PPBS, and medium-term planning, Agenda 21 reconfigured sustainable development into a cybernetic architecture for global governance — fusing stakeholder integration, metrics-based accountability, and long-term policy horizons into a managed network of public-private-civil society partnerships embedded within the United Nations.

In the mid-90s, Kofi Annan became Secretary General. He quickly turned on the ‘inefficient’ United Nations system itself, and reformed it in line with the public-private partnership model trialled through the World Commission on Dams, operating for ‘the common good’, as defined by the participating third party — the Civil Society Organisation. Wolfgang Reinicke further developed this concept, ultimately to become a 5-stage process, represented by the Trisectoral Network.

Following Kennedy’s assassination, the Planning-Programming-Budgeting System (PPBS) underwent a pivotal shift under Lyndon Johnson. While Kennedy applied PPBS cautiously — mainly to curb military spending — Johnson adopted it as a tool for expansive government reform. In 1965, Johnson issued a Presidential memorandum mandating PPBS implementation across all federal departments, heralding it as a ‘revolutionary system’ that could align national goals with resource allocation over a five-year period. The long-range program planning model became the foundation for the Great Society’s sweeping social programs19. As historian Robert Seldon noted, Johnson’s expansion of PPBS represented ‘the most important administrative development of the decade’.

The Vietnam War was the first major real-world stress test of the PPBS framework. As the war intensified, the Pentagon applied McNamara’s mechanisms of force programming, cost analysis, and systems evaluation rigorously. Every troop deployment and matériel increase required justification within the Five-Year Defense Program (FYDP), with program elements continually adjusted based on simulations, budget forecasts, and output metrics. McNamara’s planners approached the battlefield not as an unpredictable strategic arena, but as an opportunity to test their quantifiable system of inputs and outputs to be optimised20.

Robert Komer — who directed civilian-military operations in Vietnam and later authored a key analysis of the conflict’s bureaucratic logic — characterised the war as a managerial exercise in systems theory21. Civilian PPBS administrators managed Vietnam by meticulously tracking projects, deliverables, and expenditures to exert control through quantification. Vietnam became the proving ground for new styles of planning and decision-making, not only on the battlefield but throughout the supporting bureaucracy. What was originally designed as a tool to control defense budgeting ended up shaping the very conduct of the war itself.

A picture emerges.

Kennedy entered the White House as an outgoing president warned of the rising power of the military-industrial complex22. Determined to throttle its influence, he turned to Robert McNamara — a civilian technocrat — to help impose control.

But what Kennedy didn’t realise was that McNamara’s revolution — quietly engineered through RAND and financed by Ford and Rockefeller interests — was a Trojan horse. It promised efficiency and civilian oversight, but it embedded systems control at the heart of governance, capable of centralising power without oversight. And when Kennedy began to question the trajectory, he became a liability

Eisenhower Presidency (1953–1961):

The military-industrial complex expands rapidly during the Cold War, embedding defense contractors and surveillance programs across government.Kennedy’s Civilian Oversight (1961):

JFK brings in Robert McNamara from Ford to the Pentagon as Secretary of Defense and authorises the initial deployment of the Planning-Programming-Budgeting System (PPBS) to constrain defense spending.PPBS and the White House (1961–63):

McNamara implements PPBS, thus centralising decision-making in the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), effectively transferring control from the services to the executive branch.Military Resistance and Budget Constraints (1962–63):

Generals resist PPBS, which they view as a civilian takeover. Kennedy uses it to cap defense spending and resist Joint Chiefs' pressure, maintaining military budgets under $50 billion and overriding JCS preferences via economic logic.NSAM 263 and Vietnam Drawdown (October 1963):

Kennedy signs a National Security Action Memorandum ordering the withdrawal of 1,000 U.S. military personnel from Vietnam — signalling an intent to scale down involvement.Kennedy Assassination, Johnson Reversal (November 1963):

Days after JFK’s death, Johnson issues NSAM 273, reversing Kennedy’s policy and recommitting to Vietnam escalation.CIA Begins PPBS Trials (1964):

Internal CIA memos and Richard Helms’ correspondence confirm that the Agency quietly begins adapting PPBS methods.1965: LBJ Mandates Government-Wide PPBS Rollout:

Johnson mandates all federal agencies adopt PPBS — extending technocratic planning from the Pentagon to civilian departments under the banner of Great Society reform.Vietnam as a Laboratory (1965–68):

McNamara manage Vietnam like a PPBS testbed: inputs, outputs, cost-benefit metrics. Civilian analysts model war as a system of quantifiable metrics — treating Southeast Asia as a battlefield simulation.McNamara to the World Bank (1968):

McNamara becomes President of the World Bank and exports PPBS logic globally. He introduces Country Program Papers (CPPs) — five-year development frameworks that tie financial aid to performance metrics, projections, and cost-benefit analysis.Technocratic Expansion into UN Agencies (1970s):

Inspired by McNamara’s reforms, institutions like UNDP and UNIDO adopt medium-term programming aligned with PPBS and ‘indicative planning figures’.NIEO and G-77 Co-opted (1974–76):

The New International Economic Order (NIEO) demands sovereign economic planning for the Global South. In response, the UN integrates national plans into PPBS-style structures, effectively transforming calls for autonomy into mechanisms of controlled development programming.Agenda 21 and the Rio Summit (1992):

Building on NIEO, the Agenda 21 framework is adopted at the Earth Summit — embedding PPBS logic, stakeholder governance, and long-term planning into the global sustainability agenda, justified through ecological necessity.Kofi Annan Reforms and NGO Integration (1997–2000):

Secretary-General Kofi Annan reforms UN systems to formally include General Consultative Status NGOs in all parts of the organisation, institutionalising public-private partnerships and turning governance into a trisectoral model — state, private sector, and civil society — guided by the ‘common good’.The World Commission on Dams (1998–2000):

The WCD pioneers stakeholder integration through systems analysis and participatory frameworks. Civil society actors define the ‘common good’ in technical terms, framing it as a global planning mandate.Wolfgang Reinicke’s Trisectoral Network (2000s):

Reinicke develops a 5-stage model for Global Public Policy Networks — blending states, corporations, and NGOs into decision-making loops. These structures are supported by the Trilateral Commission, World Economic Forum, and other elite-coordination platforms.

The Planning-Programming-Budgeting System (PPBS) began as a lever — not for expansion, but for constraint of the military-industrial complex Eisenhower warned about. Under Kennedy, McNamara’s early implementation of PPBS served to discipline the military services, and its five-year programming cycles and cost-effectiveness metrics were designed to impose civilian control over defense planning. Kennedy wielded it as a scalpel — much to the objections of the military. The tool appeared neutral on the surface, but it masked a deeper function: it granted its controller a new method of power consolidation.

Yet Kennedy, especially after the Cuban Missile Crisis, came to question the logic itself. Broader adoption of PPBS was quietly halted, and in February 1963, JFK authorised the wiretapping of the recently dismissed CIA Director of Intelligence, Robert Amory Jr, who had been a key figure in Project Lamp, an early initiative exploring the application of systems analysis to long-range intelligence planning; effectively the intelligence counterpart to the Pentagon’s PPBS.

Though shelved at the time, it represented a formative step toward transforming intelligence into a programmable domain — one that, had it advanced under Kennedy, would have conclusively blurred the line between analysis, execution, and oversight.

The reversal came swiftly. After the assassination of Kennedy, Johnson didn’t just inherit the PPBS lever — he inverted it, to become an engine of justification. In 1965, Johnson ordered its adoption across every federal agency, transforming a Pentagon experiment into a federal operating system. The same tool Kennedy used to constrain now served to expand — rationalising spending, extending state reach and control far beyond defense. It did not empower professional judgment but systems analysts, detached from the fields they modelled. Great Society programs, foreign aid initiatives, health, environmental programmes, and covert operations were bundled into five-year plans, shielded from oversight by the language of technocracy. Meanwhile, the Vietnam War became its live stress test. Escalations were simulated, costed, and slotted into the Five-Year Defense Program (FYDP), typically with far less success than originally anticipated. As Komer and Herring would later write, Vietnam ceased to be a war in a classical sense — it became a systems management testcase, ruled through outputs by planners who had never seen the battlefield.

By 1965, the CIA’s planning, surveillance, and covert operations were absorbed into this same cybernetic logic — now coordinated with COMIREX, later routed through and sanctioned by Kissinger’s Forty Committee. Globally, McNamara's World Bank adopted Country Program Papers (CPPs), while the UN embraced medium-term plans, each replicating the PPBS schema. Development, diplomacy, and especially social justice became models of strategic control — governed not by needs, but by computational simulations with no legitimate oversight, just as in transitioned into environmental governance.

By the mid-1970s, this regime became a tripartite system of state power, enterprise, and foundation-funded civil society organisations defining what constituted social justice, and hence, ‘the common good’. What Schlesinger envisioned — a global stakeholder ‘democracy’ — emerged through perception management. Civil society, once a check on state power, was retooled into a legitimising layer of social justice, determined by data no citizen could audit and narratives no parliament could realistically control.

By the 1990s, the system reached maturity. Results-Based Management and the Millennium Development Goals, and later the SDGs, formalised governance as an algorithmic process. Decisions were not to be debated as reality progressively was replaced by modelled outputs, controlled by real-time global surveillance infrastructure constructed without public knowledge or consent. Indicators — created through global surveillance data — were treated as gospel truth, with those daring to question its many flaws deemed immoral, while the ICSU and UNESCO through SCRES and COMEST began to introduce the world to the concept of ‘ethics disclaimers’ in sciences.

Power gradually shifted away from democratic debate and to multistakeholder partnerships controlled by unelected global elites, who used the mainstream media to ensure you got the message — the science is to be trusted.

Brzezinski’s Between Two Ages was no warning — it was a manual. He detailed, precisely, the coming fusion of computation and governance, the moralisation of control, and the post-sovereign architecture of a ‘technetronic society.’

Kennedy, questioning where this was all heading, declined to serve it.

Today, the architecture is operational. AI-guided simulations shape interventions, with ‘ethical’ imperatives calculated by computer instruction. Illegitimate ‘planetary boundaries’ are invoked not to inform populations — but to constrain them. Civil society has been repurposed to manufacture legitimacy for outcomes generated in opaque models. Simulation has replaced deliberation, with those modelling the equations increasingly being reframed as religious clergy who do not tolerate blasphemy.

Even if those who designed the system itself realised its fatal flaws.

What Schlesinger envisioned, what Amory tested, what the CIA and CFR coordinated, what Kissinger operationalised, what Rockefeller engineered, and what Brzezinski outlined… has become the contemporary operating system of our world. Its legitimacy was never earned, and it was never realistically stress tested by its skeptics.

And never once was it approved by the public, because no-one bothered explaining it to them in the first place. Not because they couldn’t, but because it wasn’t in their interests to have an informed public.

This system, which began by transferring power away from the Joint Chiefs of Staff, next captured the rest of the US government, was stress-tested in Vietnam, and like a cancer metastasised through the United Nations — first capturing the G77, then the globe. It has expanded quietly, invisibly, with few even aware of its existence. And each time it fails — each missed target, each false forecast, each war — the conclusion is never doubt, but redesign, because the failure was due to lack of granularity, driving a call for even higher quality data and thus even more covert surveillance equipment. Because ultimately, the flaw is not with the design of the system itself.

And that system was, in November 1963, inaugurated in Dallas.

And with that said, here are a number of related CIA/Amory/Schlesinger links.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The price of freedom is eternal vigilance. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.