For generations, the story was simple: If you want to save the planet, start with yourself—sort your recycling, cut your carbon footprint, buy ‘green’ products, and rest assured that you’re making a small but meaningful difference.

This narrative reassures us that personal choices are the linchpin of environmental salvation, as if the sum of conscientious individuals might somehow tip the scales toward ‘planetary health.’

But behind this illusion stands a very different machinery—one that predates ‘eco-friendly’ labels and lifestyle calculators by nearly a century.

The untold part of the story isn’t recent government policy, nor the greenwashed claims of corporations that suddenly care for the planet. No—behind the facade of care—for the planet, for the disadvantaged, for minorities and the poor—a quiet arc was already forming. One that leads us, again, back to Julius Wolf’s gold clearance mechanism, and the year 1892.

Step by step, Wolf’s deceptively simple idea expanded into an empire of rent-seeking—one where every imbalance or differential could be turned into a revenue stream for the few.

In essence, Julius Wolf proposed replacing the physical shipment of gold bullion with certificates redeemable for gold held in approved vaults—typically in the central banks of major nations. Where once gold would sail across oceans to settle accounts, now only paper (or its contemporary digital equivalent) needed to move. It was efficient, rational and cost-saving.

So it’s all good, right?

Well, that’s only part of the story. Because this system also introduced a middleman—someone who could extract a cut from every transaction. That middleman became the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), which in 1930 formalised this exact mechanism—coincidentally, just as the global economy was collapsing, unemployment surging, and the foundations were laid for a second world war.

But it doesn’t end there.

Under normal circumstances, a nation’s gold reserves are finite. When a country runs out of gold, it signals that foreign creditors have lost faith in its policies, which typically crashes its currency and wages. Painful, yes—but this acts as a corrective mechanism. Eventually, the nation adjusts, policies improve, and gold slowly returns.

In this sense, gold itself is a kind of sovereign constraint—a built-in regulator that keeps governments pivoting back toward equilibrium. Limited gold supplies meant limited overreach.

But in the BIS system, gold became effectively inexhaustible—not because more of it was discovered, but because creditor nations could endlessly lend it on paper to debtor nations through certificates that were never meant to be redeemed—a mechanism now known as rehypothecation, where the same asset is pledged multiple times, creating the illusion of abundance.

And that’s exactly what happened. Cross-border debts, facilitated through the BIS and later the IMF, only ever expanded—built not on settlement, but on perpetual deferment. All the while, the world’s central bankers had just one phrase on their lips: price stability.

The issue, of course, is that while their system claims to stabilise prices—however inconsistently—it does so at a cost. And that’s the part no one talks about.

Because if the cost of short-term price stability is ever-growing debt, enforced neoliberal policy, the hollowing out of national labour incomes, and a continuous stream of immigration no nation can realistically integrate—then who, exactly, benefits from this stability?

And what, in the long run, are its consequences?

But let’s return to the core mechanism: the insertion of a mediating layer between creditor and debtor—a mechanism that claims to balance the two. Because this very same structure now appears almost everywhere you look.

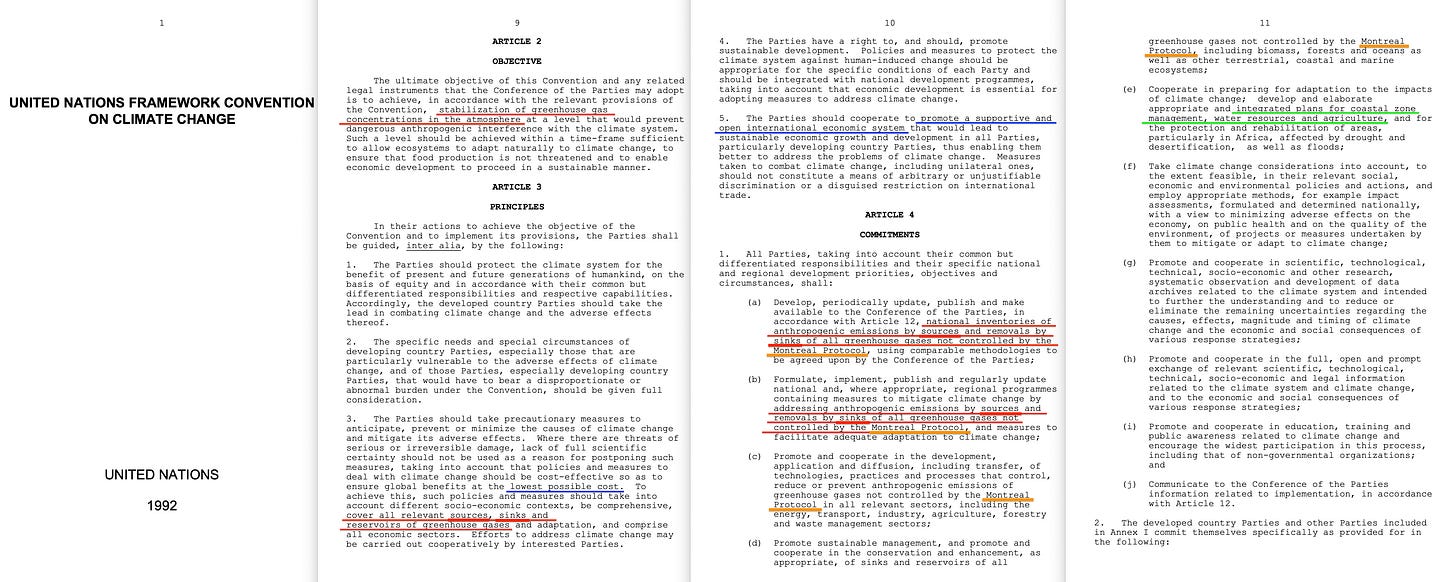

One of the most obvious examples? The Earth Summit in Rio, 1992—and more specifically, the UNFCCC treaty itself1.

The 1992 framework is, in fact, fairly blunt about its true objective: to create the need for a mediating entity between carbon sinks and carbon sources—an intermediary through which the two can gradually be brought into balance—Net Zero, so to speak.

The Montreal Protocol, for the record, is mentioned no fewer than eleven times in the UNFCCC text—and the reason is simple: it introduced the concept of emission permits, albeit without any monetisation attached. But read a little closer, and you’ll find repeated references to achieving emissions reductions at ‘lowest cost’, within the context of an ‘open and international economic system’.

Taken together, these phrases lay the groundwork for what followed—namely, UNCTAD’s proposal, also in 1992, for a fully monetised emissions permit system. First trialled in the sulphur dioxide (SO₂) markets, the CO₂ version would follow almost identically, as outlined in Combating Global Warming in striking detail.

The very same document, it’s worth noting, that openly calls for the wholesale monetisation of air and water.

Then came the Kyoto Protocol2 in 1997, followed by the creation of IETA3—the International Emissions Trading Association—in 1998. And from there, the rest is history. Carbon emissions are now publicly traded like any other commodity, and the recommendations laid out in those two UNCTAD reports from 1992 to 1994 remain remarkably intact.

Only now, this lever of control inches ever closer—not just to your industry, but progressively closer to your behaviour, and even your bank account.

The trick, of course, is the same: a mediating middle-man cashes in on assets he does not necessarily own (trees), claiming to equalise an equilibrium that cannot be accurately measured—especially given the vast unknowns of the oceanic carbon cycle.

But it doesn’t stop there.

In 1980, the UN published the Brandt Report4, led by Willy Brandt, outlining the so-called North–South divide—an imbalance to be mediated through the progressive equalisation of health, housing, education, and poverty.

But even that report was a successor. Back in 1975, the Lima Declaration and Plan of Action on Industrial Development and Cooperation5 had already called for the restructuring of global industrial development and a New International Economic Order to promote equity and cooperation. It emphasised the need for international support in industrialisation—through financial assistance, policy reforms, and, not least, the transfer of technology.

But before we go there, the NIEO also led to the Third System—the G77-precursor tripartite government structure, controlled by the Civil Society Organiation front, eventually fused into Agenda 21. And there are these… subtle hints in the documents:

...due attention should also be given to the industrial co-operatives as means of mobilizing the local human, natural and financial resources for the achievement of national objectives...

Co-operatives, in short, were what Bernstein, GDH Cole, and later Lenin described to eventually become the New Economic Policy.

And, sure, it’s not a clincher, but:

Development and strengthening of public, financial and other institutions in order to protect and stimulate industrial development...

… exactly of which ‘other institutions’ do we speak?

Increased financial contributions to international organizations and to government or credit institutions in the developing countries…

No, really. Of which ‘international organisations’ do we speak, exactly?

...strengthening of machinery and institutions to regulate and supervise foreign investment and promote the transfer of technology.

More on that in a minute. And then there’s item 44:

That urgent discussion should be continued in competent bodies for the establishment of a reformed international monetary system, in the direction and operation of which the developing countries should fully participate. This universal system should inter aiia be designed to achieve stability in flows and conditions of development financing and to meet the specific needs of developing countries;

There’s that ‘price stability’ again.

And though it’s light, there are further hints that PPBS and equivalent planning systems were already making their way into the North–South debate. The language of long-term industrial strategies, institutional machinery, continuous appraisal, and integrated sectoral planning all suggests that the logic of systems management—if not yet the name—was already being quietly normalised.

The formulation of long-term and clearly defined industrialization plans and strategies... and the introduction of concrete measures and institutional machinery for their execution, continuous appraisal and, if necessary, adjustment.

Sure, it’s early days, but it’s there.

Technology transfer is an interesting deviation from the usual principle. Because under normal circumstances, the money’s in mediating the oppressor–oppressed dynamic—where the mediating entity takes a cut from each transaction, never mind that he doesn’t actually own the quasi-monistic substance for which a balance is allegedly required.

But technology transfer is different. Here, technology flows from wealthy nations to poorer ones—often at the direct expense of the Western taxpayer. And while, yes, this still presents opportunities for the usual middle-men to skim their cut, that’s not the core intention. No, the aim here isn’t transactional arbitrage—it’s structural realignment.

As was thoroughly laid out in Inclusive Capitalism, the world today—at its telos—operates through the Sustainable Development Goals. These goals are not mere aspirations; they are converted into surveillance-based global indicators, continuously monitored and fed into Digital Twins. And it is these systems—not parliaments—that now compute what constitutes ‘health equity’, and who is deservant. All of it happens without a single soul ever casting a vote, thanks to Covid-19 and the Pandemic Treaty.

The real trick was already unpacked in the post on Inclusive Capitalism. See, by offering technology transfer on altruistic terms—funded, of course, by the Western taxpayer—developing nations are encouraged to accept equipment calibrated to the same ISO standards used everywhere else.

The result? Technology transfer doesn’t just close development gaps. It quietly builds global surveillance capacity—standardised, integrated, and interoperable—within those very same third world nations.

It’s clever, isn’t it? Not only are Western taxpayers footing the bill, but the proceeds go toward constructing the very surveillance infrastructure that ultimately works against their own interests. And this isn’t new. In fact, a while back I speculated that PEPFAR was rolled out for precisely this purpose—under the same Dubya who, to my knowledge, had never previously expressed any deep personal concern about AIDS in Africa until it conveniently aligned with America’s global health security initiative.

But it goes beyond mediating technology transfers, health inequity, economic disparities, carbon sinks and sources, and even finance itself. It reaches all the way into the Frankfurt School’s Critical Theory playbook, which—beyond spawning a vast array of DEI-instituted initiatives—has created an entirely new class of worker. Judging by the job adverts, these roles are anything but poorly compensated—typically funded by the taxpayer. The result? A colossal industry of wealth mediation, now operating along the axes of gender and race.

Take Black Lives Matter, for instance. The riots curiously led not only to a flood of donations, but to louder calls for reparations—even from countries that never had a single slave, never mind a black population.

And—true to form—when BLM organisations received $90 million in 2020 alone, who exactly benefited? Certainly not the black neighbourhoods, nor the general taxpayer, as over 20 lives were lost and more than $2 billion in damages were incurred—while countless small businesses, many black-owned, were destroyed6.

It is, quite simply, all a scam. A complete scam. The same model, fused and refitted again and again into the global system. First by Julius Wolf, with his 1892 gold certificate clearance mechanism—the world’s first operational blueprint for supranational, rent-extracting infrastructure. A clearinghouse whose very business model was managing imbalances and commodifying correction itself.

Wolf’s true legacy materialised four decades later, when the world’s central banks established the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) in Basel, Switzerland. The BIS institutionalised Wolf’s logic: central banks deposited gold, offset claims via ledger entries, and paid a fee on each transaction—monetising imbalances at planetary scale. And it worked. The BIS posted a healthy operating margin in its very first year.

But just as Wolf built the architecture for monetary flow, Eduard Bernstein laid the ideological foundations for transnational social democracy. Confronted with national crises—depressions, labour disputes, and the looming threat of war—Bernstein argued these could no longer be managed within national boundaries. The solution, he claimed, lay in international cooperation, arbitration, and federalist structures.

His vision called for a shift of policymaking beyond the nation-state—a prototype for shared sovereignty and coordinated governance. Not a utopian dream, but a reformist strategy for managing capitalism’s tension points across borders. And during the First World War, Leonard S Woolf translated Bernstein’s theory into political architecture. In International Government (1916), published by the Fabian Society, Woolf set out the working model for what would become the League of Nations—later institutionalised by Alfred Zimmern in 1919.

Woolf’s report was unambiguous: international organisations, operating under the guise of free trade and open borders, would gradually strip power from the nation-state. Economic equalisation—through tariff harmonisation and tax policy convergence—would become inevitable. Which is, of course, precisely what the IMF demands today of any nation desperate enough to accept its terms.

Julius Wolf’s seemingly simple financial idea has, over time, morphed into the foundation of today’s vast, increasingly automated rent-seeking apparatus—a global system that not only tracks health equity, racial tension, carbon, and biodiversity, but profits from every ‘imbalance’ it detects and claims to correct.

That very logic—of imbalance demanding intervention—is now transforming carbon emissions, social justice, and health inequity into managed states of global concern. Each must be carefully ‘balanced’, we’re told, setting the stage for the emergence of a full-blown ‘moral economy’, where transactions are no longer measured by price, but by the degree of ‘greater good’ they supposedly serve.

Just imagine the kind of power that falls to those who get to define what that ‘good’ is.

The foundational myth—your carbon footprint equals your ethical worth—diverts attention from the far larger reality: a system where ethics and correction have been privatised and rigged for rent-seeking intermediaries. This isn’t just about pollution or inequality—it’s about control.

The answer, therefore, is not yet more focus on allegedly ‘green’ consumption. It’s not ‘better offsets’, ‘fairer credits’, or ‘smarter ESG scores’. The answer is honesty, open debate, and democratic representation—practically the diametric opposites of the qualities on display from our elected servants at present. Because absolutely none of this is discussed with the voters, and that for good reason:

They would immediately reject it.

It’s time to rewrite the myth—because as it stands, it really only serves those who lease the planet back to us for rent.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The price of freedom is eternal vigilance. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.