Investigate the global institutional banks and you'll find that three primary ones exist: the BIS, a meta-central bank whose member central banks determine monetary policy in their respective home nations; the IMF, which enforces neoliberal policy changes in exchange for fiscal aid when the central bank cannot (or refuses to) step in; and the World Bank, broadly responsible for financing ‘the common good’.

Ah yes, and then there’s a fourth. But we’re not supposed to talk about that one.

But we’ve discussed it before — several times, in fact. Its purpose is to facilitate highly lucrative blended finance deals for private equity investors, allowing them to cash out on taxpayer largesse. Naturally, it’s not framed that way, and the bank isn’t named as such either — but that’s what its rendered purpose amounts to1.

The World Conservation Bank was first proposed during discussions at the 4th World Wilderness Congress in 1987. We’ve covered this before — in essence, the idea originated with Michael Sweatman of the WILD Foundation (who later proposed ‘Nature Needs Half’2 in 2009, arguing that 30% by 2030 wasn’t enough), and it received strong backing at the conference from David Rockefeller and Edmund de Rothschild. However, as the original proposal drew significant attention, the final version was tweaked slightly and ultimately launched as the GEF.

You see, the original proposal also had them operating the multilateral development bank (MDB) component tied to financing Debt-for-Nature Swaps — the very instruments that, inevitably, will collapse. And that, oddly enough, drew criticism. So, the central planners did what all good central planners do — they hid the operation more effectively.

In short, the most troublesome aspects of the original World Conservation Bank proposal were quietly shifted to the World Bank — incidentally, their core partner, and the institution in whose building they were based for years. These days, the GEF occupies a building several blocks away in Washington DC, thereby ensuring complete independence. But facetiousness aside — if you were to take the elements surreptitiously moved to the World Bank and restore them to the GEF, you'd have the World Conservation Bank as originally intended: a bank gorging on Western taxpayer funds, engineering usurious Third World debt-for-whatever deals (designed to fail), typically nature, but others exist. Why? Because when they collapse, the collateral ends up in, say, UNESCO Biosphere Reserves3 — gradually stripping the origin nation of its most productive natural assets. And it was precisely this pattern that drew attention in the late '80s, creating a very specific engineering problem.

When I first covered blended finance back in December 2023, I estimated that taxpayers were subsidising private equity thieves to the tune of around 92%. However, after reviewing OECD figures, it seems I was wrong — the more widely accepted internal estimate is closer to 90% (edit: the originally supplied figure of 10% is what’s contributed by the private parties — my original estimate was 2% off, not 82%).

As detailed in the earlier post on the GEF, private equity investors typically take senior equity, while the taxpayer-funded portion is structured as mezzanine (junior) debt — thus offering higher returns and lower risk for the private side. In other words, it’s a colossal transfer of public funds to private hands, with private investors seemingly participating solely to fleece the taxpayer. Except, of course, that accepting any level of risk is unacceptable to these select few, who are presently hard at work, eliminating all aspects of risk.

But precise data is carefully kept from public view, and the reason why is obvious. Why do our own politicians go out of their way to hide just how much taxpayer funding is funnelled into these so-called ‘climate investments’? Perhaps the very same reason why neither project nor finance documentation is anywhere to be found on the GEF’s website? The overwhelming majority of the money involved comes from taxpayers — yet we’re not even permitted to see quite how large… a grand larceny they presently carry out.

But highlighting the fraud embedded in one-sided blended finance is only part of the story, because so-called ‘climate finance’ is set to scale massively in the coming years — reaching trillions4 within the decade. Trillions of your taxes, handed over to sponsor billionaire-class blended finance ‘deals’ via the GEF, all designed — quite obviously — to defraud the taxpayer. Naturally, this has been obscured by routing the MDB funding component through the World Bank, yet if down the line, a World Bank–GEF merger were to take place — as an increasing amount of World Bank funds are channelled in that direction — the original World Conservation Bank begins to look far less like a conspiracy theory, and far more like… policy in waiting.

This new structure would exist to serve the global ‘common good’ — where, of course, the ‘common good’ is currently defined by our contemporary (yet shifting) doctrine: the Sustainable Development Goals. And the SDGs ultimately boil down to three main pillars: the social, the economic, and the ecological5. And the Long-Term Vision for 2050 makes that rather explicit.

Yet this vision ultimately outlines the need for balancing the sustainable production of ecosystem services rendered by the natural assets with the sustainable consumption thereof for sakes of human well-being. And that, in turn, leads us back to the question of balancing humanity with nature (lest all those alleged zoonotic diseases kill us all yet again) — a topic that traces straight back to the 1968 UNESCO Biosphere Conference.

A key to understanding how this plays out in practice came in 2019 with the release of the Berlin Principles6 — the follow-up to the 2004 Manhattan Principles, also known as One Health. Together, these outline a system for balancing not man, but the biosphere on a global scale.

But one important, ethical development tied to the 2019 Berlin Principles is worth highlighting. To quote directly:

'Underpinning the Berlin Principles is a broad One Health ethical framework... the impossibility of protecting human health in isolation from the health of other animals and the environment.'

And this, quite legitimately, is no joke.

We can similarly step back to the Manhattan Principles7, which state [6]:

… fully integrate biodiversity conservation perspectives and human needs…

Especially given in context of [8]:

Restrict the mass culling of free-ranging wildlife species for disease control to situations…, or wildlife health more broadly

And to this end [10]:

Increase investment in the global human and animal health infrastructure…, vaccine / pharmaceutical manufacturers, and other stakeholders.

Yet, ultimately, this comes down to nature conservation, which require 17%8… no, 30%9… wait, more10… half11… actually, it will never be enough, will it [2]?

Recognize that decisions regarding land and water use have real implications for health. Alterations in the resilience of ecosystems and shifts in patterns of disease emergence and spread manifest themselves when we fail to recognize this relationship.

In short — we need, ideally, to protect the entire world, or zoonotic diseases will kill us all, exactly as they did in 1968, 1976, 1997, 2003, 2005, 2009, and 2020.

What the Berlin Principles then clear up is that humanity is to be viewed as just another specie — another animal to be managed by central planners in the name of Planetary Health. Incidentally, Steven Osofsky, who co-authored the Manhattan Principles, was also involved in the Rockefeller/Lancet Planetary Health initiative12, while William Karesh co-authored the Berlin Principles (above).

Small world, indeed.

Consequently, all aspects of human well-being are to be viewed through the lens of ecological balance which in turn yields a call for system regulation. Incidentally, precisely this was stated in the 1982 World Charter for Nature.

‘In the decision-making process it shall be recognized that man’s needs can be met only by ensuring the proper functioning of natural systems and by respecting the principles set forth in this Charter‘.

Man’s needs, according to the Charter, can only be met through balance with nature — while the Berlin Principles go further, asserting that human health itself requires integration with nature.

Humanity, thus, is just another specie on planet Earth; one that requires management, and — if its impact is deemed excessive — potentially reduction. A point particularly Dennis Meadows of the Club of Rome has emphasised.

Ergo, once humanity is ethically categorised alongside ‘the other animals’, all aspects of the economy and society must likewise be managed — by a small, self-appointed technocratic philosopher-king elite — for the sake of the Earth Charter and the IUCN’s planetary stewardship. And since land-use planning and the environment is central to that stewardship, the World Conservation Bank naturally becomes an instrument of it too, operating — so we’re told — for the ‘common good’.

But two other primary global financial institutions exist — the BIS and the IMF. Through neoliberal conditionalities, the IMF effectively enforces Leonard S. Woolf’s 1916 vision for the gradual erosion of national borders (International Government) — paving the way for an increasingly holistic world order, controlled by General Consultative Status NGOs. If the BIS withholds support from a local central bank during a crisis, the IMF steps in to impose structural, neoliberal adjustments. Over time, this dynamic helps accelerate the breakdown of national sovereignty, eventually creating the conditions for the IMF’s functions to be folded into the BIS itself.

But how?

Here’s one possible path. The first step is a transition to central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). These would then be tied to a global asset class — much like money was once pegged to gold. Only this time, the anchor is likely to be a ‘green’ asset: carbon emission credits. In other words, carbon-backed CBDCs.

Once every nation has adopted a such system, the next phase would be to gradually align the value of all currencies — or alternatively, to stabilise them relative to an external reference currency, much like European currencies were pegged within ranges ahead of the Euro. With that alignment in place, all CBDCs could then be merged into a single, global, carbon-backed digital currency.

In our current system, the IMF specialises in cross-border currency issues. However, once all currencies are synchronised, that role becomes irrelevant — and its remaining functions can then be absorbed by the Bank for International Settlements. That would leave us with just two global financial institutions.

At this stage, while the World Conservation Bank will ostensibly operate ‘for the common good’ — championing planetary stewardship — the BIS, through its network of member central banks, will continue working with national governments to set monetary policy, leaving fiscal policy in the hands of those same governments. But here lies the problem: governments are often irrational, beholden — at least in theory — to popular consensus. Just imagine — a government carrying out… the will of the people? No, to this end we need to strengthen our democracy, ensuring that doesn’t happen.

The solution? Remove fiscal policy from the meddling hands of the tedious prole and place it in the safe custody of a deserving technocrat — namely, the central bankers. This is precisely what the Fabian Society proposed in their 2023 pamphlet In Tandem — though, of course, they insist it’s merely about ‘influencing’ fiscal policy. Just as, no doubt, they merely ‘influenced’ Truss and Kwarteng out of office not long ago for daring to not clear policy with the BoE before announcement.

This model is then scaled globally, with fiscal responsibility handed over to local central banks. From there, national central banks are gradually folded into the BIS, leaving all fiscal and monetary policy-setting with the BIS. Then follows the merger with the World Conservation Bank. Why? Because this enables fiscal policy to be directed, on a global scale, toward the so-called ‘common good’. In the end, it leaves us with a single global bank controlling all credit — exactly as outlined in the Communist Manifesto13.

But there are still a few issues — chief among them that troublesome proles might retain some degree of control through private ownership of assets. This, however, can be addressed logically: through increased taxation and inflation, while simultaneously directing public anger at the ‘greedy Wall Street banker’. The solution then becomes a new type of currency that outlaws ‘speculation’ — ie saving — marketed under the appealing label of ‘positive money’.

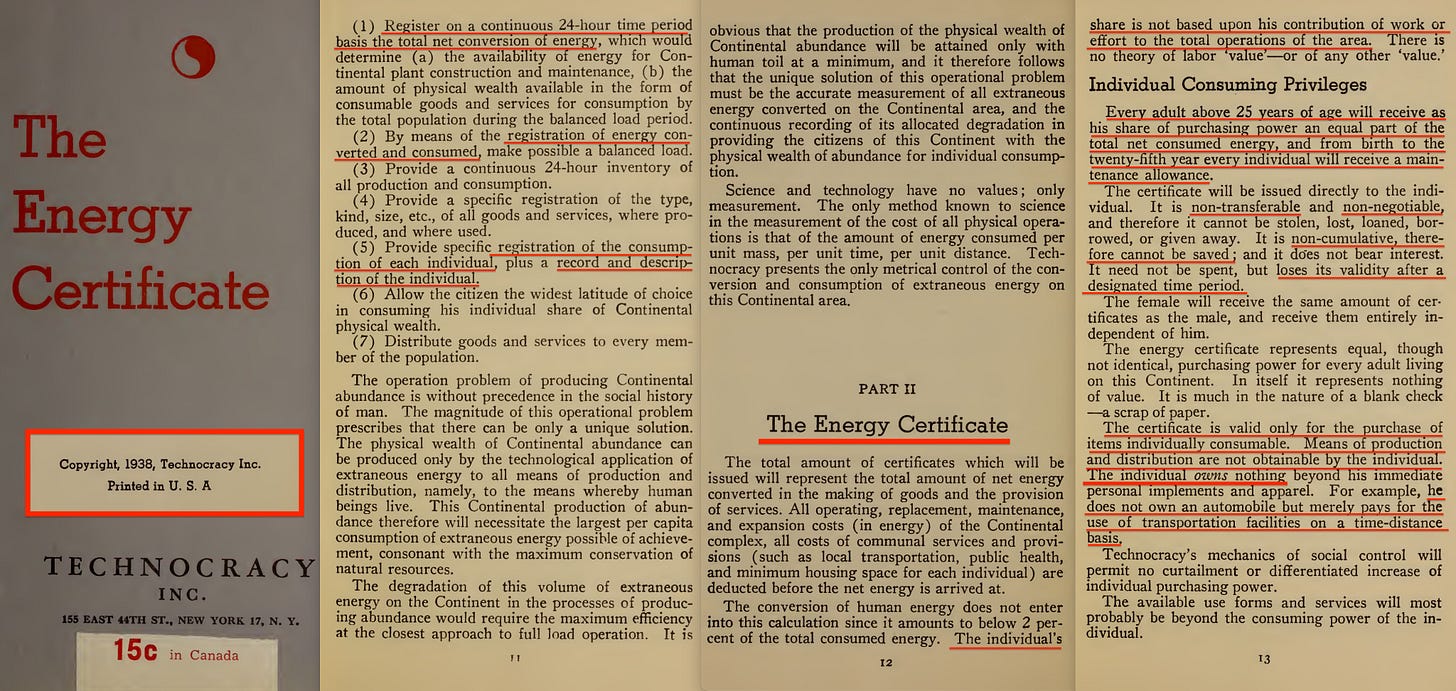

This currency would bear no interest and exist solely for transactions. It’s sold as a way to cut out greedy Wall Street bankers, but in reality, it hands full control of credit to the central banks. And if tied to carbon emission credits, such a currency could be issued with expiry dates — conveniently eliminating the age-old habit of saving for a rainy day. Incidentally, this is the direct inverse of what Technocracy, Inc. proposed in 1936 with their energy certificates14. The same year, as it happens, that Keynes published The General Theory — front-run by the RIIA, naturally.

The next logical issue becomes asset ownership — specifically, how a complementary, interest-yielding savings currency might function. By this point, the solution is surprisingly straightforward: if you issue the savings currency as a CBDC backed by carbon sequestration (i.e., trees), then its interest payments can be made in the standard, time-limited trading currency. In other words, ownership of natural assets would generate interest in the temporal, trading currency — mirroring the cycles of nature almost perfectly. In theory, of course, because in practise you cannot with any level of accuracy predict how effective a carbon sink a patch of rainforest will be in any given year. The calculation is quite simply too chaotic to know — especially considering mature rainforests due to decay practically are ‘net zero’ already, and thus shouldn’t even count positive. And never mind the oceans being the largest carbon sink…

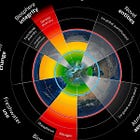

Regardless, from there, the currency backing could logically shift to the alleged meta-crisis and thus the components defined within the Planetary Boundaries framework — enabling the central banking elite to phase out any remaining holdouts by continuously shifting the weighing of individual asset types backing the CBDCs. In the end, only a select few — the rightful Omega Point captains — would remain at the helm of Spaceship Earth.

It all perhaps sounds a bit crazy, doesn’t it? And — sure — the sequence might not transpire in exactly the order laid out above. That’s the nature of forward projection, it’s difficult. Especially when it comes to chaotic systems — like the climate. Those, in fact, quite simply cannot be forward predicted at all.

But the reality is this: all financial systems are currently being integrated, harmonised, and aligned. And the organisation orchestrating this process is the Financial Stability Board, operating out of Basel — conveniently in the same building as the Bank for International Settlements. Their remit? Regulating central banks, harmonising fiscal policy, and advancing the agenda of ‘green’ finance through initiatives like the Network for Greening the Financial System15.

And by July 2025, their next president will be Andrew Bailey16 — who, by sheer coincidence, also happens to be the current Governor of the Bank of England. The very institution set to reap enormous rewards from the Fabian Society’s In Tandem pamphlet, proposing to shift fiscal policy to the Bank of England.

The notion of an economy centred around the ‘common good’ — or values — can also be traced to Mark Carney, who in 2021 published Value(s)17, a book grounded in the same conception of the common good that Eduard Bernstein, the revisionist Marxist, articulated back in 1899 — principles I’ve discussed repeatedly. Carney, incidentally, ran the FSB from 2011 to 201718 and has only recently taken up the presidency of the RIIA19 — the very organisation now busily drafting papers on precisely the issues the FSB brings to the public a little further down the line. That, of course, is no coincidence. It never is.

When UNCTAD published its two Combating Global Warming volumes in 1992 and 1994 — laying out the strategy to monetise carbon credits, air, trees, and virtually every other ‘ecosystem service’ you depend on — it was Michael Grubb’s reports for the RIIA that had effectively already front-run the agenda.

But we can go even further back. Between 1931 and 1935, the RIIA effectively front-ran Keynes’s 1936 General Theory by crafting the very monetary policy framework upon which his report relied. And further still — to 1926, and Alfred Zimmern’s The Third British Empire, which outlined a future world governed by elite think tanks such as the RIIA.

In other words, not only do the two clearly coordinate in rolling out RIIA-aligned policies — they appear to be doing so in pursuit of their own version of the ‘common good’. And that ‘good’, it appears, aligns with the full-scale fusion of the world’s major international banks into a single entity in control of global credit — exactly as Marx and Engels outlined in 1848. One that will, in all likelihood, be based in Basel.

And though it’s often referred to as ‘Hjalmar Schacht’s bank’, the reality is that one of the conditions of the Young Plan — preceding the creation of the BIS — was the reform of the German Central Bank, carried out under Allied direction.

Most people have never heard of the Financial Stability Board20. Fewer still understand what it actually does. Officially, it was created in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis to monitor the global financial system for ‘vulnerabilities’ and promote coordination among national regulators and international institutions21.

The FSB does not regulate in the traditional sense. It doesn’t issue binding laws, nor does it sign treaties, and it holds no formal enforcement power. What it does instead is far more effective: it sets global standards through soft law — recommendations, guidelines, and best practices — which are then enforced by central banks, embedded in IMF conditionalities, and adopted wholesale by G20 governments. In other words, it writes the rules of the global financial game without ever needing a democratic mandate22. Incidentally, much like the RIIA operate, except their long-term strategic recommendations are turned into policy by the Fabian Society, and implemented by Labour Governments, such as those of Keir Starmer and Tony Blair.

The scope of its work is staggering. It indirectly governs everything from capital adequacy ratios23 to the regulation of crypto-assets and stablecoins24. It leads the push for cross-border payment interoperability and the design of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs)25. It coordinates policies of member states — ensuring fiscal and monetary tools align with ‘systemic stability’. It even spearheads the integration of climate risk into financial supervision, driving the adoption of frameworks like the TCFD and enabling the enforcement arm of the green transition.

And this, of course, includes transition plans — which gradually require banks, insurers, and asset managers to align their portfolios with net-zero targets and planetary boundaries. These are the foundations of a new regulatory regime in which access to credit, insurance, and capital will increasingly depend on your alignment with ESG metrics, SDG indicators26, and ‘common good’ objectives.

Which brings us to the role of the FSB in the broader scheme outlined above. Because the FSB is not simply a post-crisis coordination forum. It is the institutional linchpin binding the World Bank’s environmental monetisation schemes, the BIS’s monetary centralisation, the IMF’s fiscal leverage, and the GEF’s blended finance laundering operation into one integrated global system. It is the cybernetic switchboard through which everything connects — regulation, finance, environmental stewardship, and the global digital transition, including the harmonisation of digital infrastructure for programmable money. And it even provides the ‘justification’ — that all of this is necessary to preserve financial stability27 in the face of planetary crisis.

In this system, the World Conservation Bank (or its modern proxy, the GEF) becomes the environmental arm, tokenising nature and driving debt-for-nature swaps under the cloak of ‘climate finance’. The BIS — through its member central banks — issues the monetary frameworks, aligning all currencies through CBDCs and eventually tying them to green assets like carbon credits. The IMF gradually sees its traditional role in currency management rendered obsolete, and its remaining mandate can then be folded into the BIS’s wider supervisory network. And through it all, the FSB ensures that no element falls out of step.

By July 2025, Andrew Bailey — Governor of the Bank of England — will take over as president of the FSB. This is no coincidence. As with Carney before him — himself a former FSB head and now president of Chatham House28 — there is a clear continuity of vision, personnel, and agenda. The same institutions, the same elite networks, writing the same rules for the same global transition.

What we are witnessing is not merely financial reform, but institutional convergence. A controlled demolition of monetary, fiscal, and sovereign independence — replaced by a single, integrated framework administered from Basel, justified by ecological necessity, and presented as morally indisputable.

The Financial Stability Board is not the endgame — it is the conduit. Its purpose is to harmonise, align, and integrate. Once the fusion is complete — once monetary issuance, fiscal policy, ecosystem finance, and digital infrastructure are fully interoperable — it will no longer be needed. Like all good transition mechanisms, the FSB was never meant to last. Rather, it was the midwife to a new financial order — one that no longer needs coordination… because it by then already is unified.

And with it, all the scaffolding is being locked in. The Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures29 (TCFD) has already laid the groundwork, now being scaled up through the International Sustainability Standards Board30 (ISSB), setting the global baseline for ESG compliance. The Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) — an alliance of central banks birthed through the FSB — ensures that monetary tools themselves are re-engineered around climate metrics. And through the UNEP Finance Initiative31, even private banks and insurers are being corralled into the same architecture, aligning their capital allocation with biodiversity scores, climate scenarios, and Sustainable Development Goal trajectories.

Soon, your carbon credit balance, your CBDC wallet, and your ESG score may all sit atop a unified digital identity — regulated not by national law, but by transnational frameworks and automated compliance layers. Governance by metric.

Because in this new world order, law becomes secondary. What matters is ethical alignment — with transition plans, climate disclosures, and planetary boundaries. Governance is no longer about rules. It is about standards, incentives, and… cybernetic control loops. The moral economy will replace the market economy, with Plato’s philosopher kings wearing central bank credentials.

A future long imagined, in fact, by the Global Interdependence Center32, headquartered within the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia — home to Henry Steele Commager’s 1975 Declaration of Interdependence, which calls openly for a ‘new world order’. Not of nations, but of networks. Not of sovereignty, but of systems.

A single, global central bank in full control of credit, dictating the global ‘common good’, and determining who qualifies as compliant. Under its governance, humanity is no longer sovereign, but simply one species among many — managed, monitored, and optimised for planetary equilibrium. It may appear a utopia to those who imagine themselves in the cockpit of Spaceship Earth33.

But for everyone else, it will be the architecture of ‘degrowth’ and — managed decline.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The price of freedom is eternal vigilance. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.