A Nature-Based Solution

Last October, while media attention focused on wars and elections, 1,400 organisations gathered in Abu Dhabi1 to approve a 103-page document that will indirectly shape whether you can get a mortgage, whether your pension fund can invest in certain companies, and whether businesses you depend on can access affordable credit.

The document is called Nature 2030: One Nature, One Future2, the Programme of the International Union for Conservation of Nature for 2026–2029.

The IUCN is not a household name, but its classifications are: the Red List of Threatened Species3, the Global Ecosystem Typology4, the World Database of Protected Areas5. These sound like scientific reference tools, and they are, but they are also the construction of an ontology — a systematic account of what exists and how it should be categorised.

Before anyone can measure biodiversity, someone must decide what counts as an ecosystem, what counts as threatened, what counts as a Key Biodiversity Area. The IUCN makes those decisions, and because the IUCN is trusted, those decisions propagate outward into law, insurance, lending, procurement, and portfolio construction.

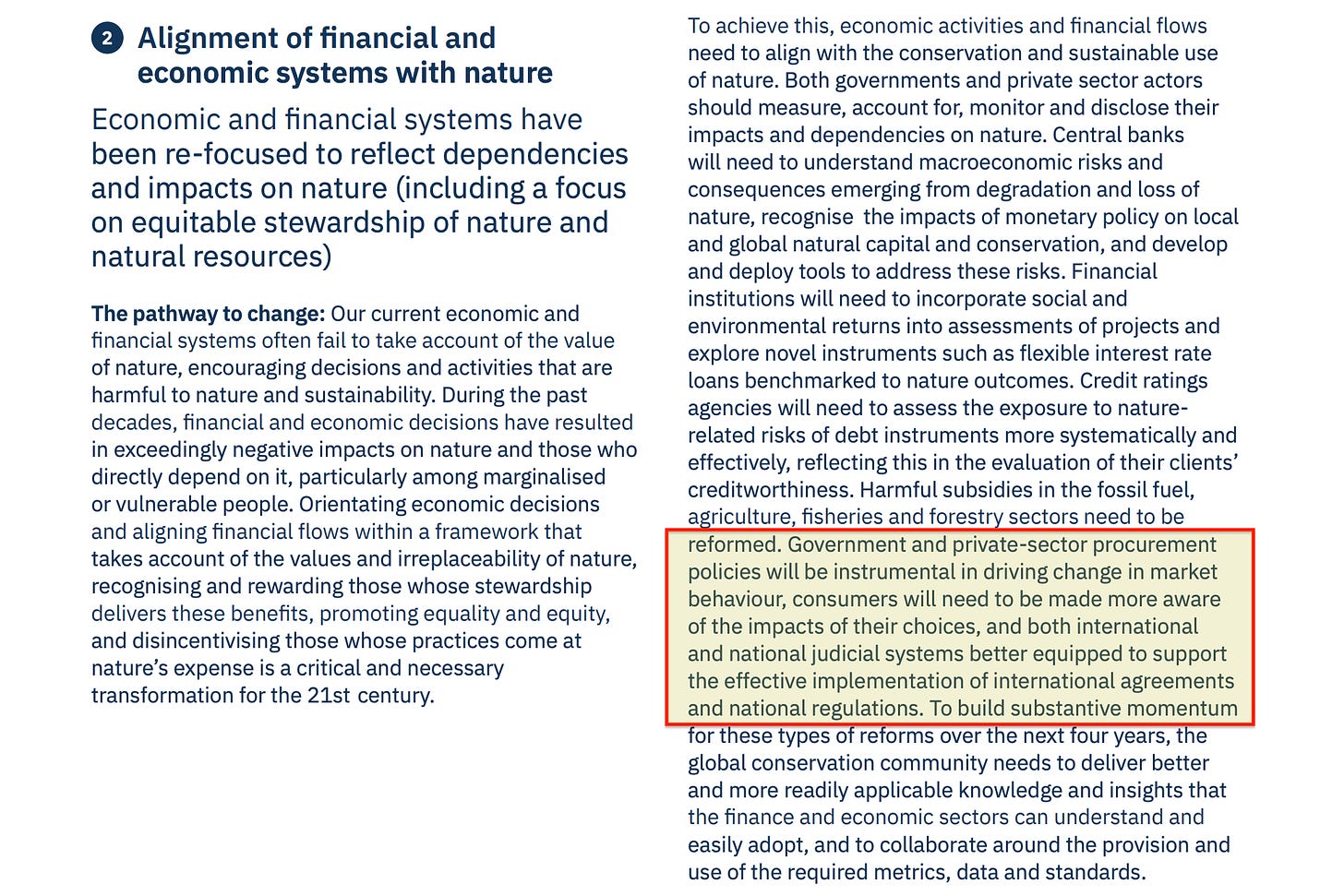

The 2026–2029 Programme extends this role into territory that will surprise anyone who thinks of conservation as tree-planting and wildlife documentaries. The document explicitly states that central banks ‘will need to understand macroeconomic risks and consequences emerging from degradation and loss of nature’, that financial institutions ‘will need to incorporate social and environmental returns into assessments of projects’, and that credit rating agencies ‘will need to assess the exposure to nature-related risks of debt instruments more systematically and effectively’.

Elsewhere, the Programme states that ‘harmful subsidies in the fossil fuel, agriculture, fisheries and forestry sectors need to be reformed’, and that ‘government and private-sector procurement policies will be instrumental in driving change in market behaviour’. The word ‘harmful’ is doing significant work here. A subsidy is classified as harmful if it fails to internalise projected environmental costs — costs derived from models forecasting emissions, temperature changes, and economic damages decades into the future.

The harm is not observed; it is computed. The policy consequence, however, is concrete: exclusion from procurement channels that increasingly require alignment with these frameworks.

That language is worth reading twice. A conservation organisation is describing the integration of its metrics into the machinery that determines what is financed, and on what terms.

Whether the architects intend this as benevolent planetary management is completely beside the point. The purpose of a system is what it does.

The Architecture

The IUCN occupies an unusual position in global affairs. Founded in 1948, it operates as a hybrid body in which governments sit alongside charities, scientific institutions, and Indigenous peoples’ organisations. This structure gives it credibility that purely governmental bodies lack, while its state membership gives it reach that NGOs cannot match. When the IUCN produces a standard, it’s generally adopted.

The Programme reveals an organisation that understands exactly how standards are adopted. One passage identifies the need to find ‘partners whose reach extends to financial institutions, major government departments, ratings agencies and legislatures’. Another signals where legal enforcement is heading, identifying the need for ‘new relationships with less traditional international organisations’ for species conservation — and naming UNODC, the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, the UN Convention against Corruption, Interpol, and the WHO.

When conservation strategy requires partnership with organised crime and corruption conventions, environmental violations are being repositioned as criminal matters. Ecocide need not be formally adopted as a crime6 if the enforcement infrastructure is already being built through existing transnational frameworks.

A third passage describes ‘scaled-up communications that senior decision-makers in these institutions will pay attention to’. This amounts to targeted integration with institutional gatekeepers — financial, legal, and criminal — rather than public awareness campaigning.

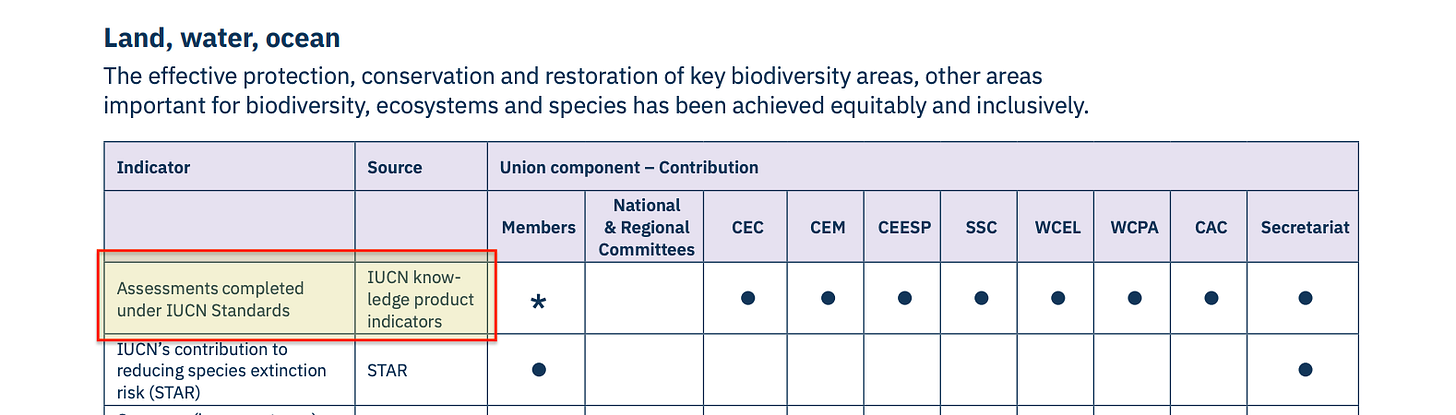

The mechanism works through certification. IUCN standards create assessable, certifiable objects: a Key Biodiversity Area7, a threat category8, a ‘nature-positive’ performance rating9. The Programme explicitly tracks ‘Assessments completed under IUCN Standards’ as a core indicator of success.

Perform the assessment and you become legible to the system; skip it and you do not exist in the relevant databases.

The real gate is the accredited assessment, the approved methodology, the authorised verifier — rather than formal legislation. You can operate without certification, but you operate in a system designed to make uncertified operation progressively more difficult, more expensive, and more isolated from the channels through which resources flow. No verifier, no credit; no credit, no finance.

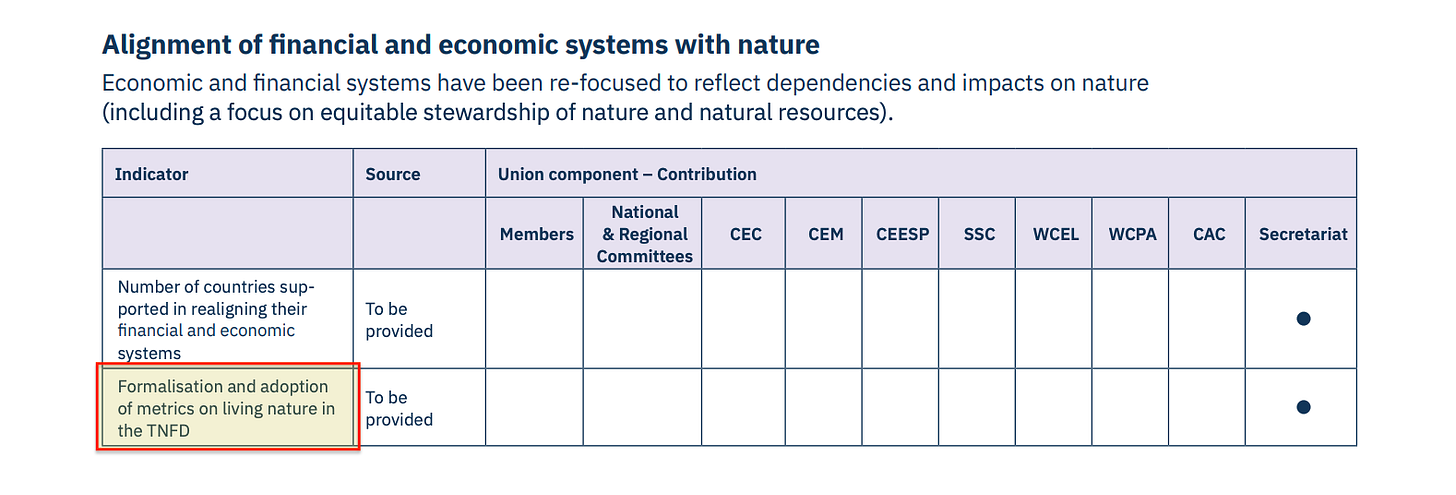

These certifications become passports. The Programme tracks the ‘formalisation and adoption of metrics on living nature in the TNFD’ — the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures10 — as a measure of success. The TNFD began as voluntary guidance, but the European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive11 now requires large companies to disclose against comparable frameworks. As disclosure regimes converge, TNFD becomes the template that regulation tends to copy.

What starts as best practice becomes expectation, then requirement, then the baseline below which you cannot operate in mainstream markets.

Organisations face a choice: either they measure their activities using approved metrics, report according to approved frameworks, and demonstrate compliance with approved standards, or they encounter friction.

The friction is primarily financial. Your cost of capital rises as lenders price in unmeasured nature-related risk. Your procurement eligibility narrows as public and corporate buyers adopt nature-positive sourcing policies. Your counterparty risk flags increase. Your insurers and investors begin asking questions you cannot answer because you lack the certified assessments. You do not get banned; you get progressively de-risked, de-prioritised, and de-platformed from supply chains that run through the measured channel.

The Programme is explicit about this, describing ‘Government and private-sector procurement policies’ as instruments for ‘driving change in market behaviour’. The rails of ordinary economic life get wired to nature-related criteria as defined by IUCN’s indicator frameworks.

The Products

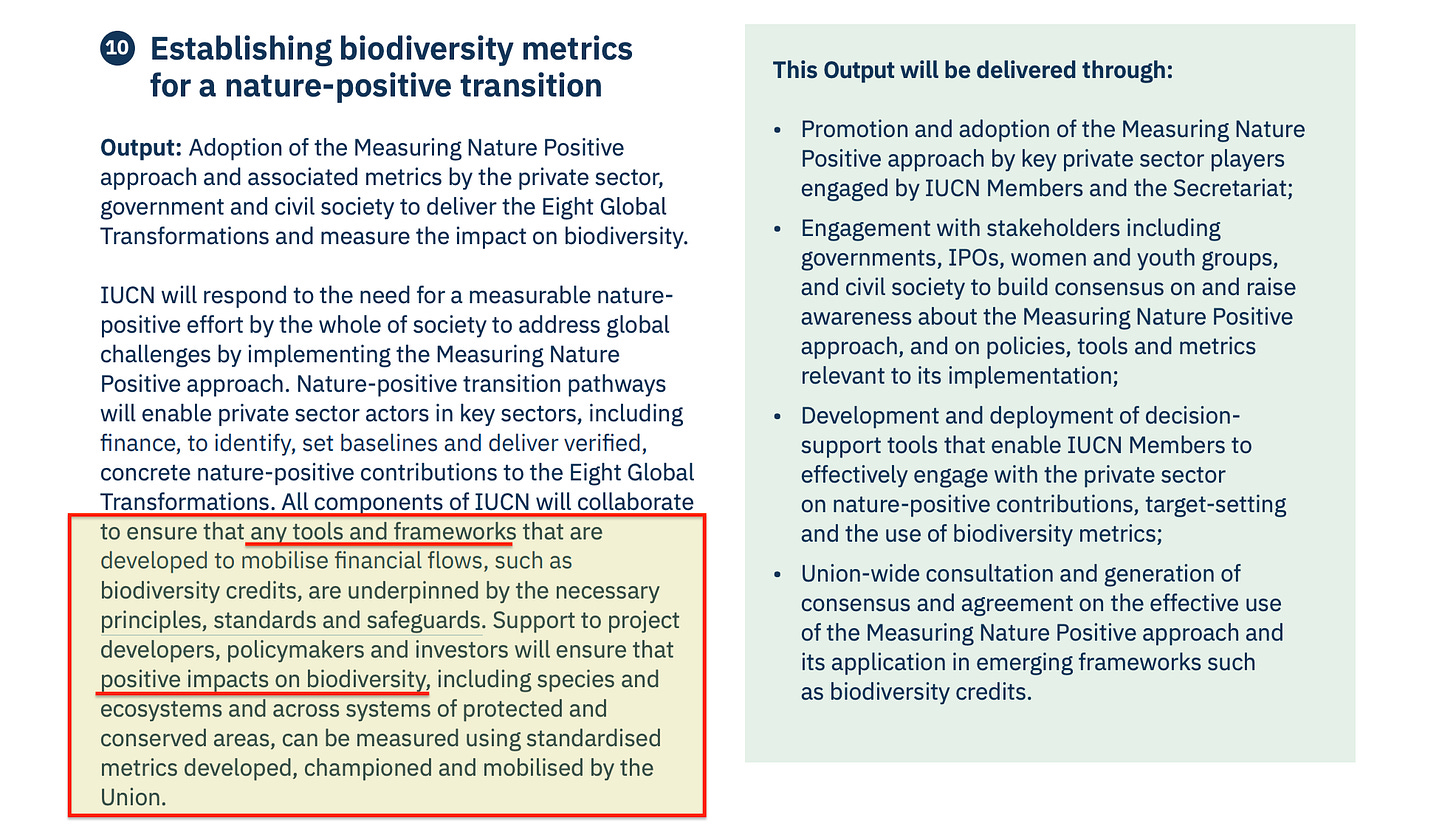

One passage makes the financialisation unmistakably concrete. The Programme commits to ensuring that ‘any tools and frameworks that are developed to mobilise financial flows, such as biodiversity credits, are underpinned by the necessary principles, standards and safeguards’. It promises that ‘positive impacts on biodiversity, including species and ecosystems and across systems of protected and conserved areas, can be measured using standardised metrics developed, championed and mobilised by the Union’.

The IUCN does not merely develop metrics; it champions them (advocacy) and mobilises them (deployment into institutional infrastructure). This is an organisation actively wiring its measurement products into the financial system.

Biodiversity credits are the signature product — tradeable units representing verified contributions to biodiversity. To trade something, you must standardise it. You cannot trade a forest, because every forest is different, but you can trade a ‘verified, concrete nature-positive contribution’ measured against a ‘standardised metric’ and certified by a trusted authority.

The IUCN is building exactly that infrastructure.

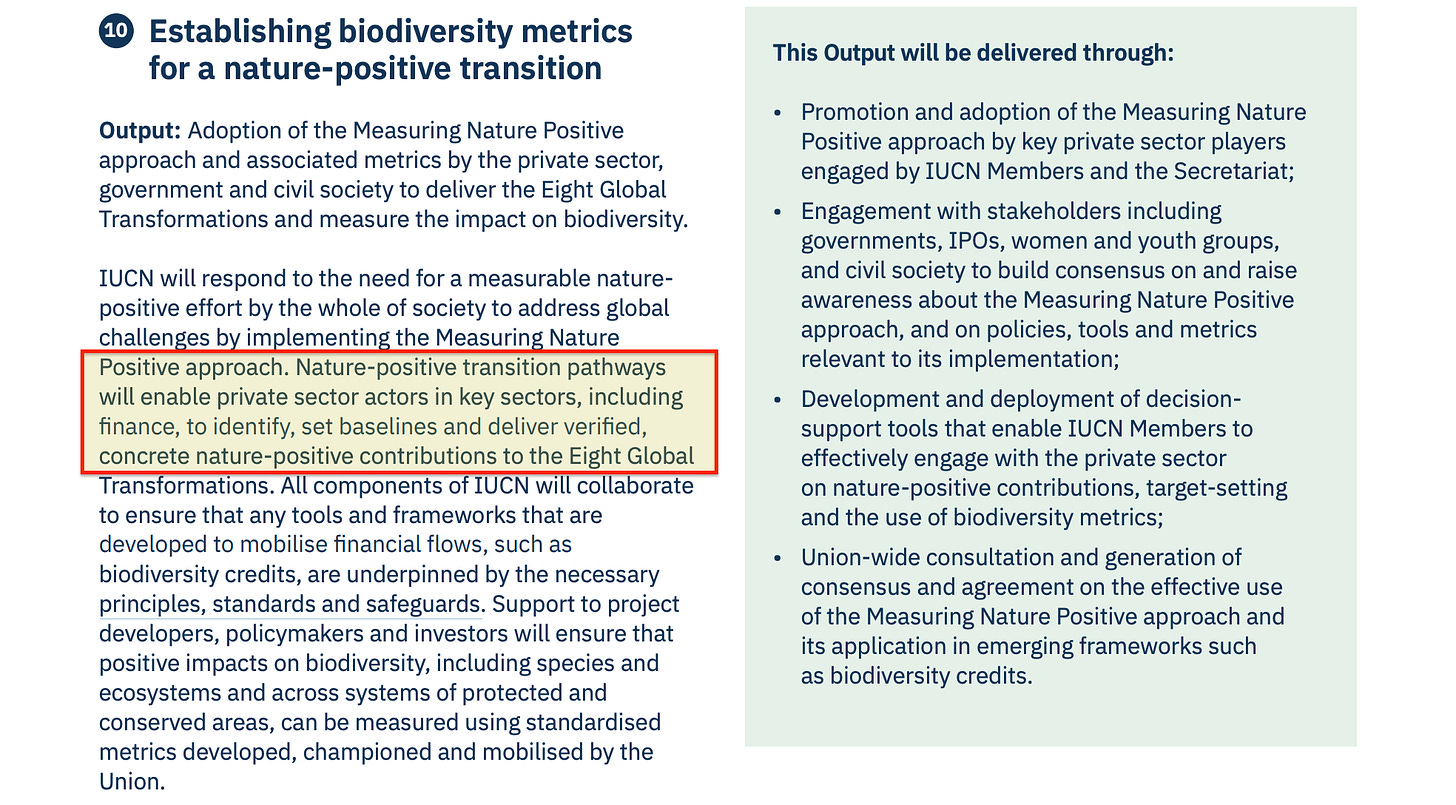

The Programme describes ‘nature-positive transition pathways’ that will ‘enable private sector actors in key sectors, including finance, to identify, set baselines and deliver verified, concrete nature-positive contributions’. Baselines, verification, standardised metrics: this is the vocabulary of audit culture, applied to ecosystems.

Nature stops being a place and becomes a standard; a new asset class. A messy wetland becomes Asset Class T1.112, legible to a spreadsheet in London or New York.

The Crisis Permission

Why would sovereign nations and global corporations accept such a framework? The Programme answers this directly, describing itself as responding to ‘unprecedented planetary crises’ including ‘biodiversity loss, the climate emergency and pandemics’. It frames IUCN as operating at ‘the nexus of knowledge, policy and action’ to address ‘interlinked global crises’ that can only be managed ‘by working together as a Union’.

That is the complexity premise: the problems are too interconnected for siloed response, too planetary for any single nation, too unprecedented for ordinary politics. Therefore: anticipatory models, standardised metrics, coordinated response, conditional finance. Crisis is the justification; interoperability is the mechanism.

The framework plugs into the Planetary Boundaries model of dashboard governance — nine quantified thresholds beyond which Earth systems become unstable. The boundaries provide the dashboard, and when the model shows a line approaching red, intervention is justified. Science defines the limit; the system enforces it.

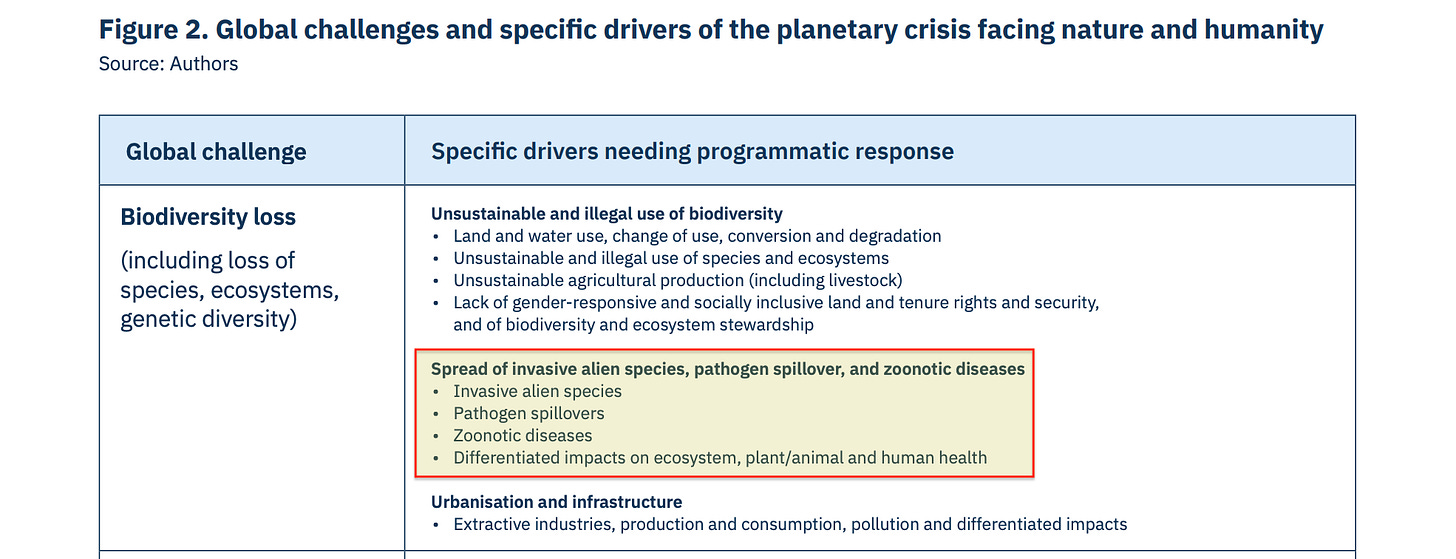

The inclusion of pandemics is significant. The Programme contains a dedicated ‘One Health’ pathway integrating biodiversity and health sectors. The same driver table that identifies ‘financial, economic, legal, and trade and investment systems’ as causes of biodiversity loss also lists ‘pathogen spillovers’ and ‘zoonotic diseases’.

Nature conservation and health emergency governance are treated as a single integrated domain.

This matters because it connects the conservation apparatus to the emergency apparatus. The Stimson Center’s work on ‘Complex Global Shocks’13 uses nearly identical vocabulary — interlinked, cross-sectoral, requiring coordinated response. The UN Secretary-General’s ‘Our Common Agenda’14 proposes an Emergency Platform15 for exactly such scenarios. The IUCN Programme builds the measurement substrate that any such platform would require: standardised categories, shared indicators, reporting infrastructure, finance conditionality.

This is convergence-by-interoperability rather than formal coordination. Different documents share the same control grammar: standardised perception, coordinated response capacity, accelerated intervention.

The Lineage

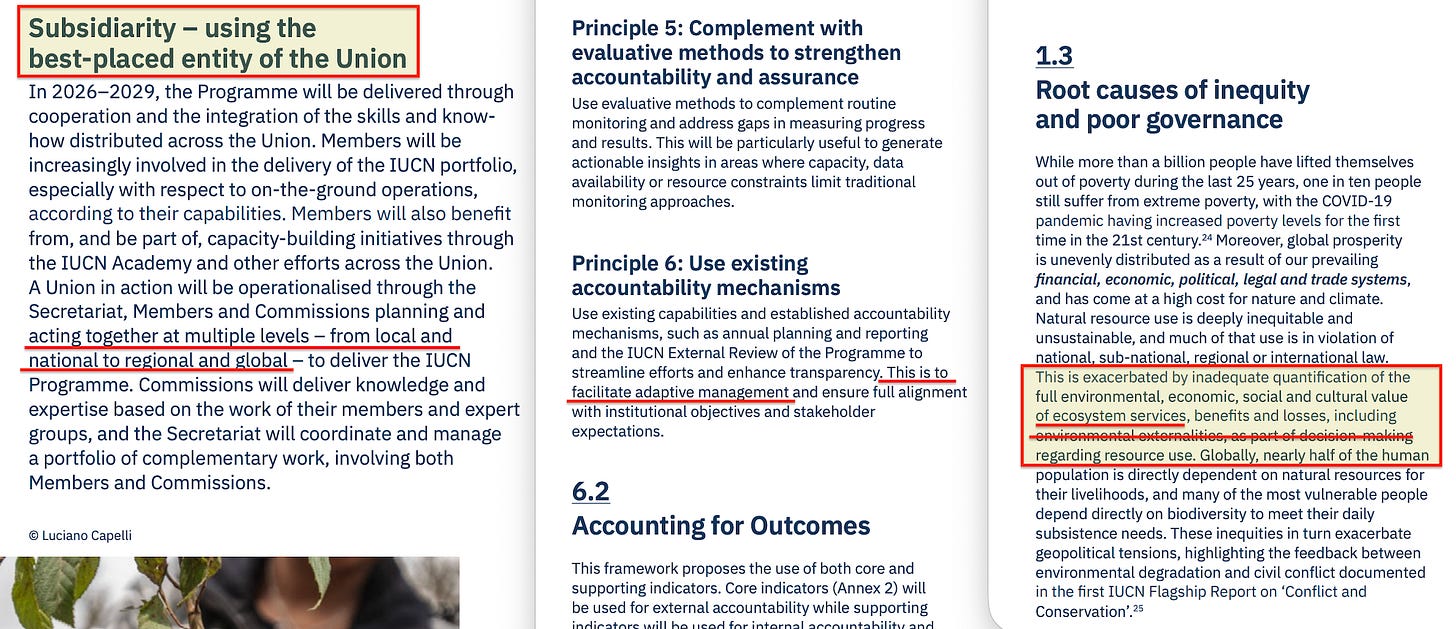

The Programme’s operating logic has a name, even if the document does not use it on every page. The Convention on Biological Diversity Ecosystem Approach16, codified in the twelve Malawi Principles, provides the template: management decentralised to the lowest appropriate level; ecosystems understood as interconnected systems requiring integrated planning; trade-offs acknowledged and managed; adaptive management built in as a design requirement.

The Programme operationalises each principle. It frames action through subsidiarity — using the ‘best-placed entity’ — while maintaining centralised parameters. It explicitly foregrounds trade-offs, noting that solving one ecosystem problem can create another, and therefore requires ‘integrated, cross-sectoral planning’ that treats ecosystems as interconnected. It calls for quantifying the ‘full value of ecosystem services, including externalities’ — internalising nature into economic calculation. It pushes landscape-scale conservation linked to long-term target frameworks extending to 2050, and it treats change as inevitable, managing within a ‘nature–global change nexus’ rather than preserving a static baseline.

The accountability section states that transparency and existing mechanisms are used to ‘facilitate adaptive management’ — the learn-and-tighten governance loop that allows the system to refine itself based on its own outputs.

This is the Ecosystem Approach rendered as a governance machine: landscape-scale, trade-off aware, valuation-driven, feedback-updated, and designed to travel across jurisdictions via common standards.

The Feedback Loop

The Programme includes an accountability framework with multiple layers: accounting for Outcomes, Outputs, ‘catalytic roles’, Resolutions and Recommendations, and ‘contributions to nature’.

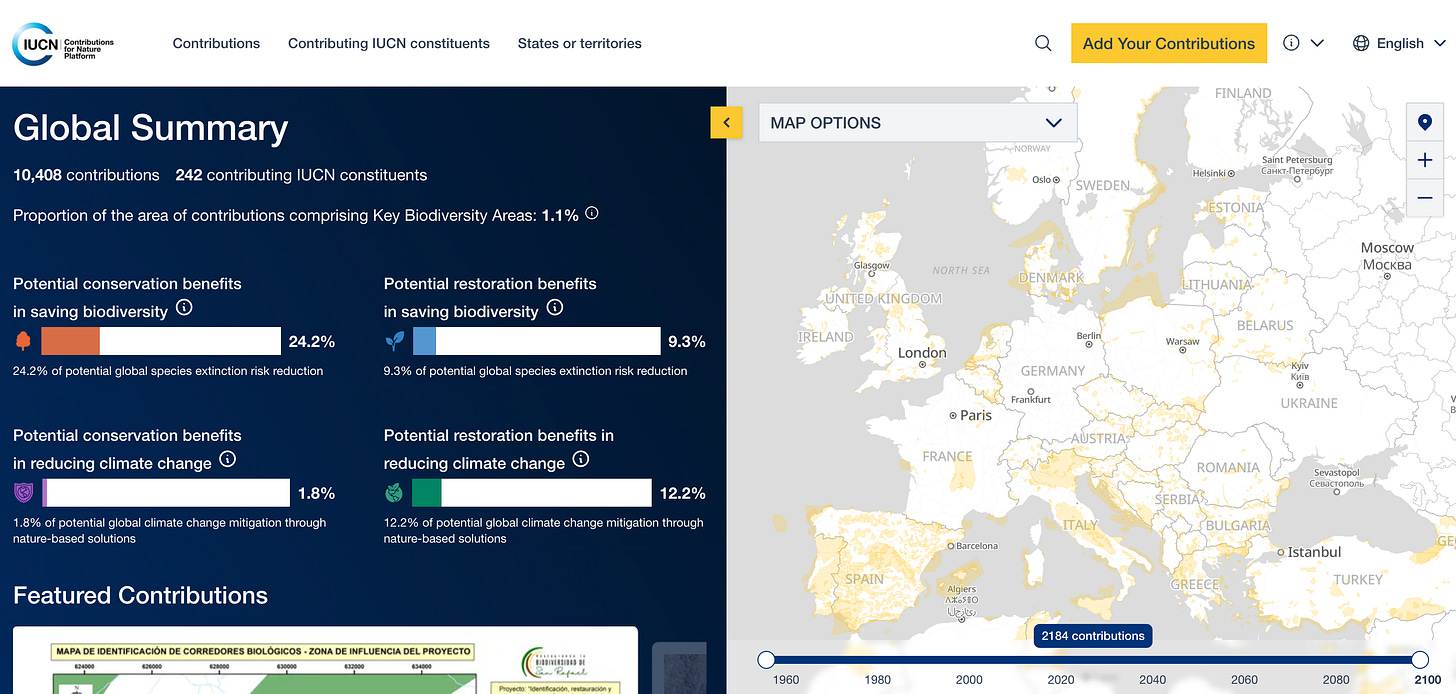

A platform called Contributions for Nature17 already tracks over 10,000 documented conservation actions by member organisations.

Data flows upward through standardised reporting channels, gets aggregated into annual reports and progress assessments, and informs revisions to standards and indicators. The system observes its own effects and adjusts.

One passage makes this explicit: the accountability framework is designed as ‘a dynamic instrument, evolving over time to best align with the institution’s growing needs and capabilities’. Initially focused on ‘core indicators’, it will ‘progressively incorporate more results-level indicators, offering a more comprehensive view of the Programme’s impact’.

That is a ratchet. The direction of travel is one-way: more indicators, more reporting, more comprehensive measurement. Current limitations in ‘data collection mechanisms’ are framed as problems to overcome, and as sensing capacity grows, the framework expands to use it.

An external review of the previous programme recommended that it become ‘less descriptive’ and ‘more directive’, with ‘greater Union-wide alignment’ and ‘clearer reporting on impact and progress’. The recommendation was adopted. They are explicitly optimising for directive capacity.

The Enforcement Rails

The Programme operates through two parallel enforcement channels.

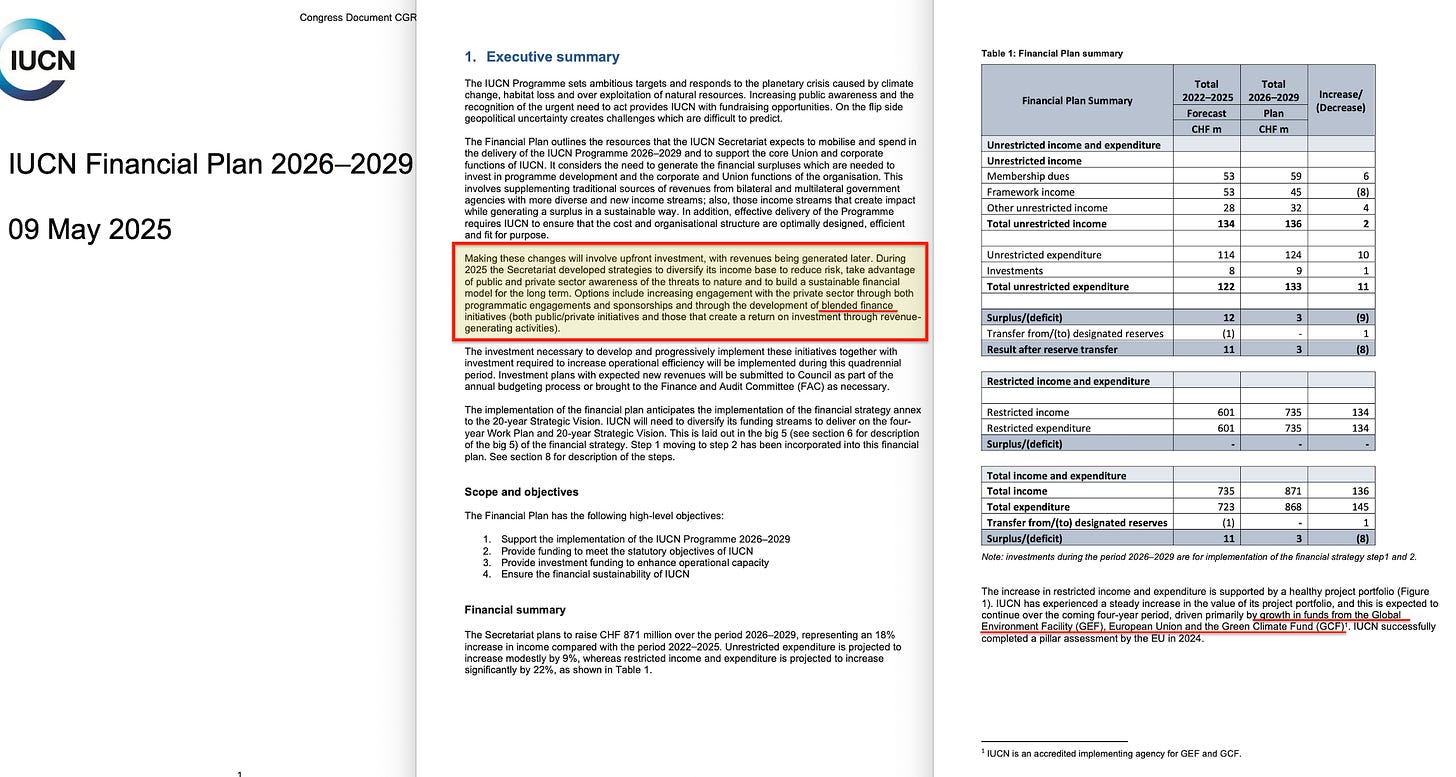

The first is financial. Central banks are named as integration targets for ‘nature-related risks’. Credit rating agencies are expected to assess exposure ‘more systematically’. Procurement policies are positioned as market-behaviour drivers. The associated Financial Plan18 introduces a KPI regime monitored by the Finance and Audit Committee, explicitly linking financial oversight to the Programme’s core indicators, while also proposing ‘blended finance initiatives’ and noting IUCN’s accredited implementing role for GEF/GCF.

The second is legal. The Programme describes work through the World Commission on Environmental Law19, compliance-and-enforcement networks, and judicial institutes. It elevates ‘preventing and reducing crimes that affect the environment’ and uses ‘follow the money’ language for illicit financial flows. The anti-money-laundering framework is migrating into conservation.

Both channels take IUCN metrics as inputs and translate standards into consequences: one raises your cost of capital, the other creates legal exposure.

Stewardship

The Programme uses the word ‘stewardship’ repeatedly. Indigenous peoples and local communities are described as ‘natural resource stewards’. The financial transformation is framed as promoting ‘equitable stewardship of nature’.

Stewardship, etymologically, is the management of another’s property. The steward operates within parameters set elsewhere. To participate in the measurement system is to be transformed into something the system can see, and tools shape users as much as users shape tools.

The Time Horizon

The 2026–2029 Programme is not a standalone plan. It operates within ‘Nature 2030’20, which operates within a ‘member-driven 20-year Strategic Vision’ extending to the mid-2040s. The four-year cycle is a stage-gate in a generational infrastructure project.

This creates a form of temporal arbitrage. The IUCN membership voted for the Programme, but the IUCN membership is not humanity, and the membership that voted will not be the membership that lives under full implementation. Democratic legitimation happens at one moment while implementation extends across decades. The technical apparatus compounds while political attention moves elsewhere.

The pattern is familiar from other international governance structures, such as the United Nations agencies: technical committees develop standards and refine indicators according to twenty-year strategic visions, a Secretariat maintains administrative continuity, and a General Assembly provides democratic cover on electoral cycles.

The planning outlasts the democratic oversight.

By the time the ‘more comprehensive view’ is operational, the politicians who approved the framework are no longer sitting at the table, ‘representing the people’.

What Is Being Built

The IUCN Programme is one node in an emerging architecture that includes the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework21, the Paris Agreement, the TNFD disclosure standards, central bank climate risk frameworks, and proposals for UN emergency platforms.

Once governance is expressed as indicators, it becomes interoperable across domains, and the same metrics that inform a public health or conservation assessment can feed a credit rating, a procurement decision, a portfolio screen.

The Programme’s stated vision is ‘a just world that values and conserves nature’. The architecture it builds is a world where nature is valued because it is measured, conserved because conservation is the condition of financial access, and just according to indicators defined by those with convening authority.

The document describes this as operating ‘at the nexus of knowledge, policy and action’. That phrase is worth parsing. Knowledge means sensing: the Programme names AI filters, environmental DNA, citizen science, and satellite imagery — the apparatus that perceives. Policy means standards: the indicators, thresholds, and definitions that interpret what is sensed. Action means enforcement: the finance conditionality, procurement restrictions, and legal compliance that translate interpretation into consequence.

Sense, interpret, act, adjust: the cybernetic loop, expressed in institutional vocabulary.

The Programme does not hide any of this. It celebrates ‘mainstreaming nature into all sectors’, which means there is no outside. It commits to ‘accountability framework evolution’, which means the system can tighten itself. It names central banks, credit agencies, and legislatures as targets, which means the system knows where power actually sits.

Perhaps we should notice what is being built while it is still being built, rather than waking up to find that the parameters of ordinary life have been rewritten by documents we never read and frameworks we never understood — while the media had us guessing who was and wasn’t on Epstein’s island.

The Template

The architecture described in this essay may seem novel. It is not.

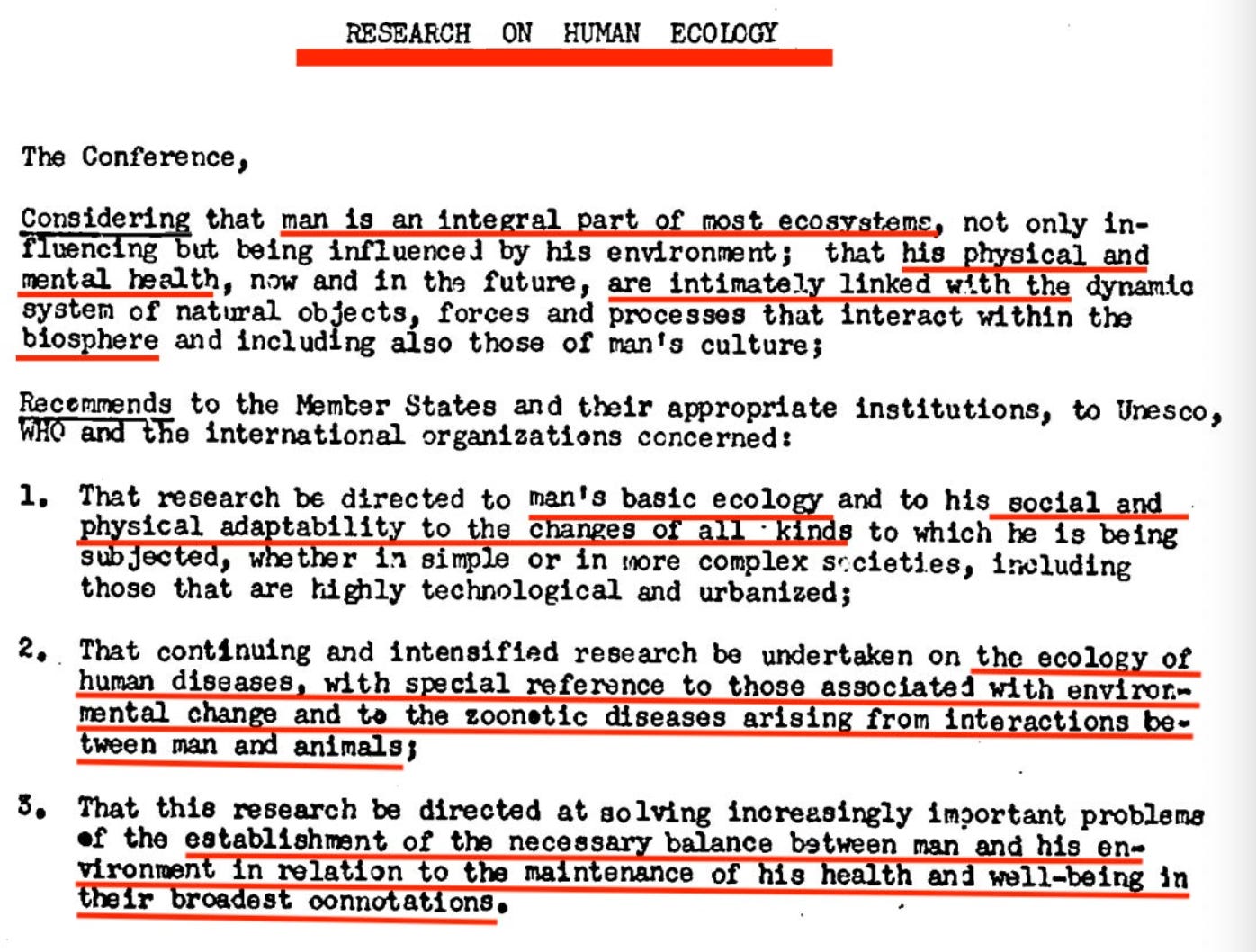

In September 1968, UNESCO convened the Intergovernmental Conference on the Scientific Basis for Rational Use and Conservation of the Resources of the Biosphere in Paris22. The conference produced twenty recommendations. Recommendation 3.2 called for ‘continuing and intensified research on the ecology of human diseases, with special reference to those associated with environmental change and to the zoonotic diseases arising from interactions between man and animals’.

Recommendation 3.3 directed this research toward ‘the establishment of the necessary balance between man and his environment in relation to the maintenance of his health and well-being in their broadest connotations’.

One Health. Planetary boundaries. The balance that must be established between man and his environment. The vocabulary was written fifty-eight years ago. What the IUCN Programme 2026–2029 represents is not a new idea but a completed implementation schedule.

In the meantime, a global surveillance grid was developed, Digital Twins built to model its data, producing a wealth of indicators that can be used for the sake of control.

Al Gore and Leon Fuerth’s Anticipatory Governance — delivered.

The architecture is now fully mapped, and so is the implementation. Ethics defines the objective; systems theory provides the mechanism; money enforces the outcome.

The governance model is stakeholder capitalism — with IUCN explicitly looking for new partners. The monetary mechanism hardly requires elaboration. The systems theory is pervasive — artificial intelligence, adaptive management, cybernetics, anticipatory governance, black-box modelling, NGFS-IIASA scenarios, IPCC reports, conditional CBDC transactions…

The ethic is planetary stewardship.

Imperialism as Efficiency

In 2023, the Bank of England and the Bank for International Settlements quietly completed Project Rosalind, a working prototype for a digital pound. Among the use cases tested: payments that release only when a child completes household chores, and transactions that assess the recipient before funds move.

Find me on Telegram: https://t.me/escapekey

Find me on Gettr: https://gettr.com/user/escapekey

Bitcoin 33ZTTSBND1Pv3YCFUk2NpkCEQmNFopxj5C

Ethereum 0x1fe599E8b580bab6DDD9Fa502CcE3330d033c63c

Another head of the hydra - thank you for your ongoing and intensive efforts to reveal as much of the whole as you can esc.

What has really hit me in the face since reading all your assiduous research on how the world really runs is just how anti-democratic it all is, has been. Prior to a deeper understanding I might have used the term un-democratic to describe the pieces that I had limited knowledge of. But un-democratic is wholly inadequate. I now believe that what has been called democracy has never existed. It has always been a chimera, and in the Information Age it became a psyop. The title of your Substack is ‘The Price of Freedom is Eternal Vigilance’. That is precisely the point, and points precisely to where the failure has been. The death of newborns is often termed ‘failure to thrive’. This is the diagnosis for democracies worldwide, but unlike babies it is in every case a matter of a lack of vigilance. But it wasn’t to be. I have a friend well on in his 70s who graduated from Berkeley in 1968. You must understand that graduating from that particular institution in that particular year places one at the birth of one of histories singularities. My friend remarked many years later that there were 2 kinds of graduates from Berkeley that year, a rather cohesive group that wanted to change the world and a rather atomized one full of individuals that wanted to start careers and families. My friend says the cohesive group emerged from an activist campus life and took jobs in academia, government, ‘social work’ and media. He remembers being very aware of them during that tumultuous year, as were his like mined compatriots, and that he and all his career and family minded classmates viewed them as fast burning candles that would soon burn out, irrelevant to the future and to the permanent things. He told me just a few years ago: “How wrong we were, and how naive. We were the very first wave of the baby boomer generation to emerge into the world and take over its reigns, but what we didn’t realize is that the reigns had been taken from us. That group of misfits(we thought) would change the world right out from under us. That we never fought back is perhaps this nations biggest mistake.”