Beyond Great Taking

The money in your bank account could be converted into shares in a failing bank over a single weekend, without your consent and without a court order.

This is a description of powers that already exist, have already been used, and are about to become dramatically faster to execute, and far more wide-reaching.

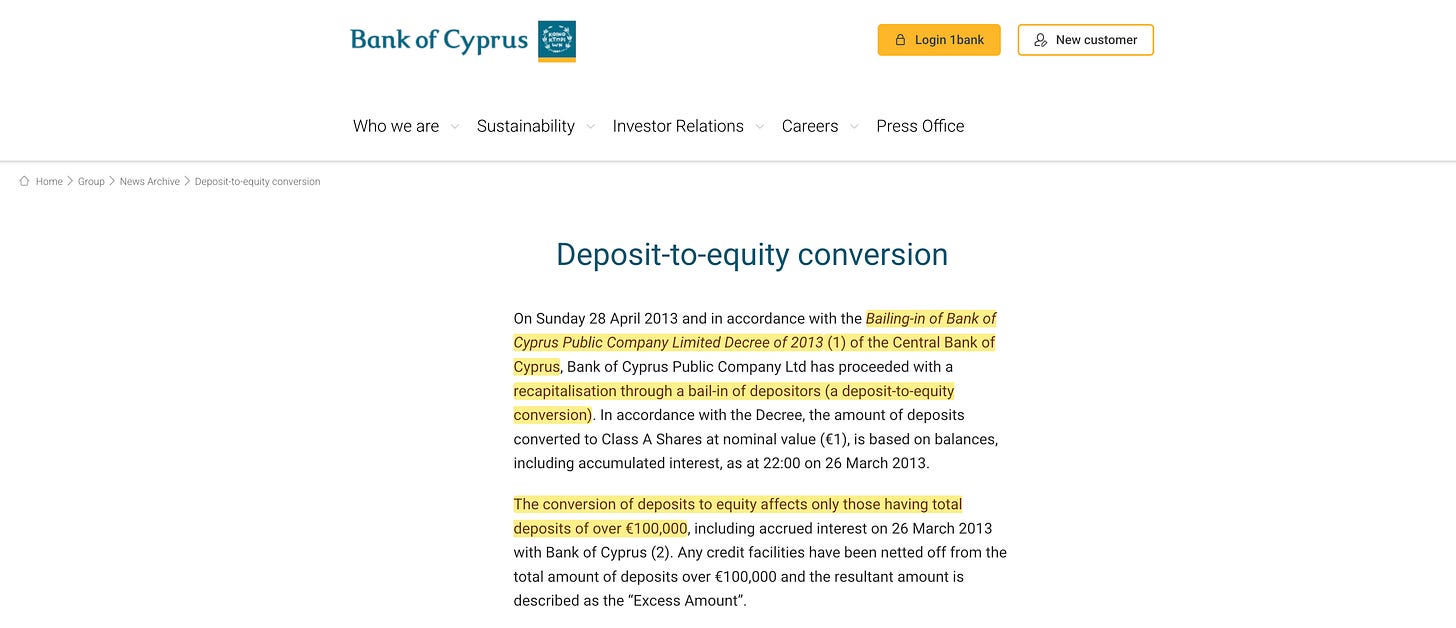

When Cyprus restructured its banks in March 20131, depositors discovered on a Monday morning that a portion of their savings had become equity in institutions they had never chosen to invest in2. The mechanism that made this possible has since been refined and adopted across every major economy.

Meanwhile, central banks are building digital infrastructure that will allow similar operations to settle instantly (and irreversibly), eliminating the procedural delays that have historically given people time to react.

This article explains how that process works: the legal status of your deposit, the hierarchy that determines who gets paid when a bank fails, the post-2008 regulations that let authorities write down your claim without asking permission, and the digital systems now being assembled that will make the whole sequence execute at the speed no human can realistically contest, while including far more assets.

Your deposit is a loan to the bank

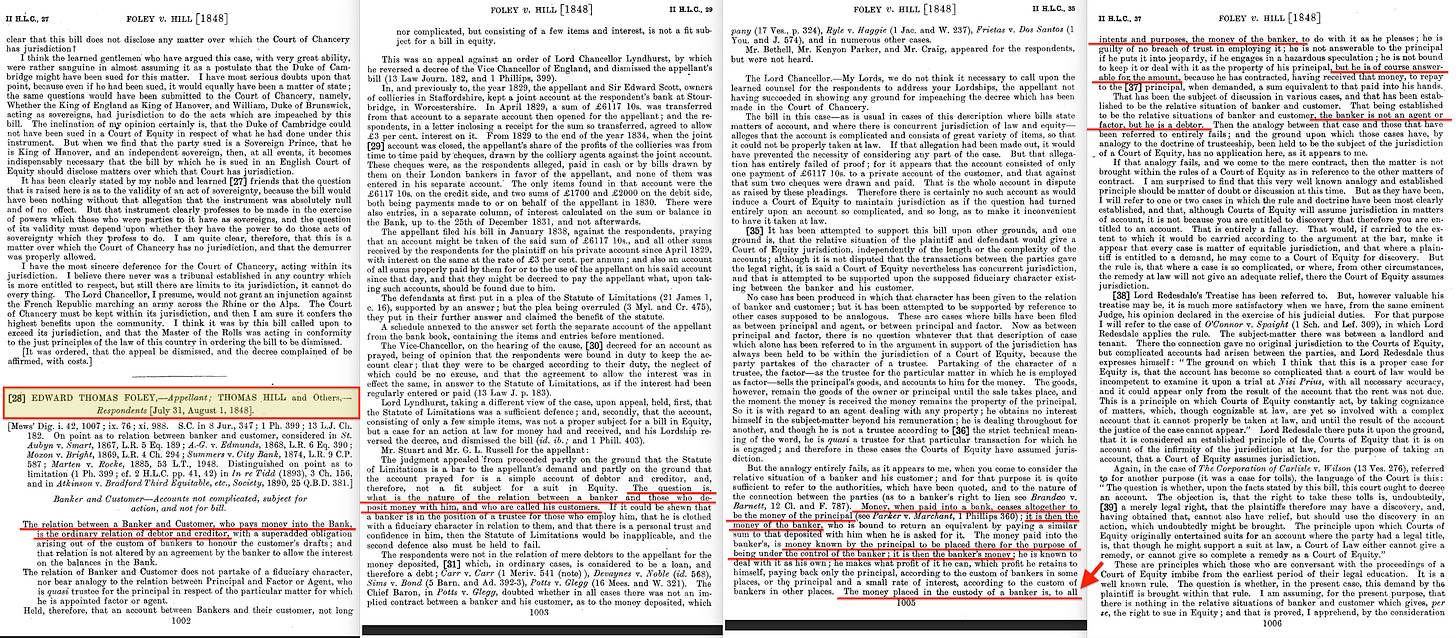

When you place money in a bank account, you perhaps believe you are storing your property in a secure location. The law sees the transaction differently. Under the precedent set by Foley v Hill3 in 1848 and maintained ever since, a bank deposit creates a debtor-creditor relationship: you hand over legal title to the cash, and in return you get a contractual claim against the bank — a promise that they will pay you back upon request. The bank owns the money. You own an IOU.

This distinction matters enormously when a bank becomes insolvent, because property and contractual claims get entirely different treatment. If you had stored gold coins in a safe deposit box, those coins would remain yours regardless of the bank’s financial condition. But because your deposit is legally a claim rather than property, it enters the queue of obligations that the failed bank must satisfy, and that queue is processed in a strict order.

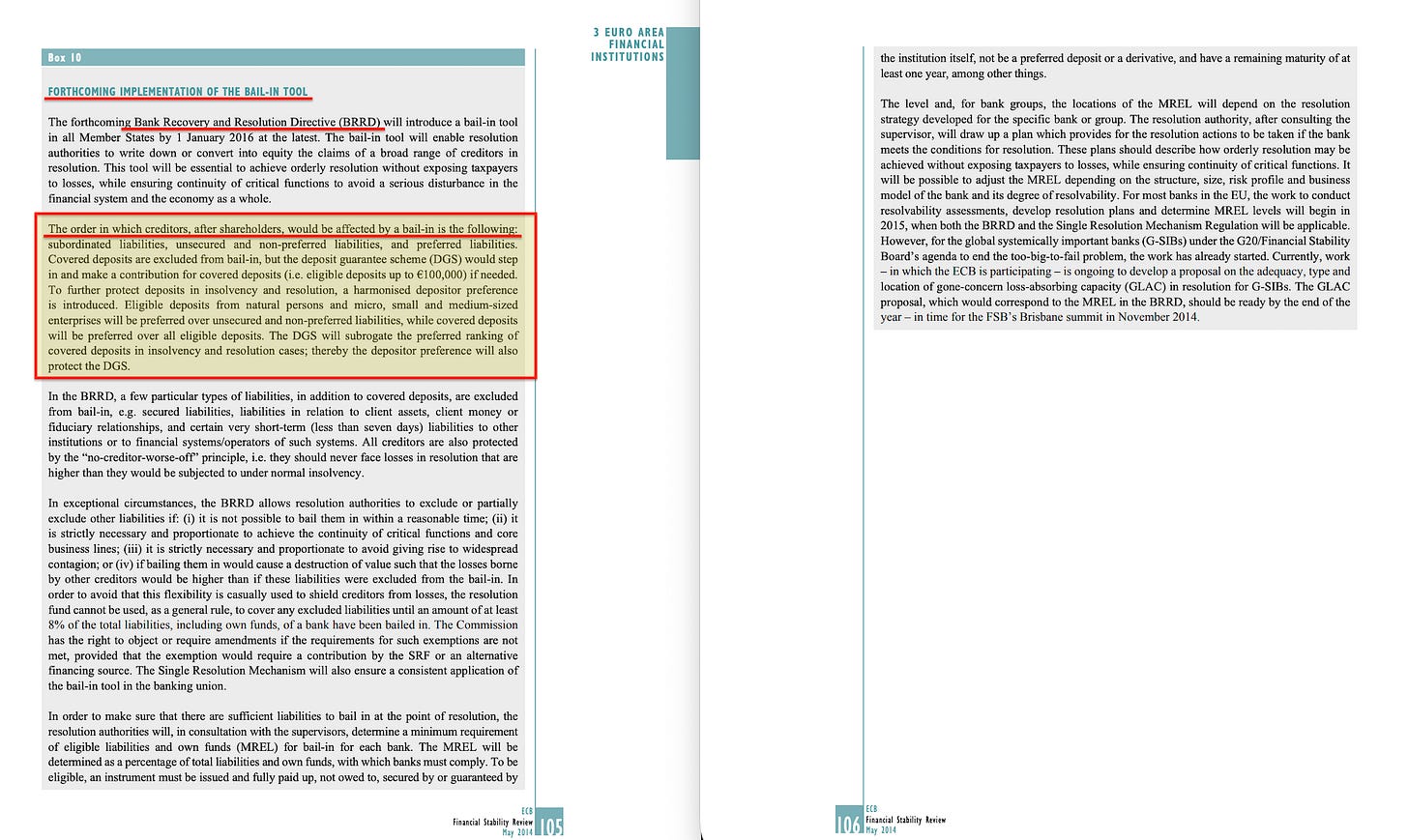

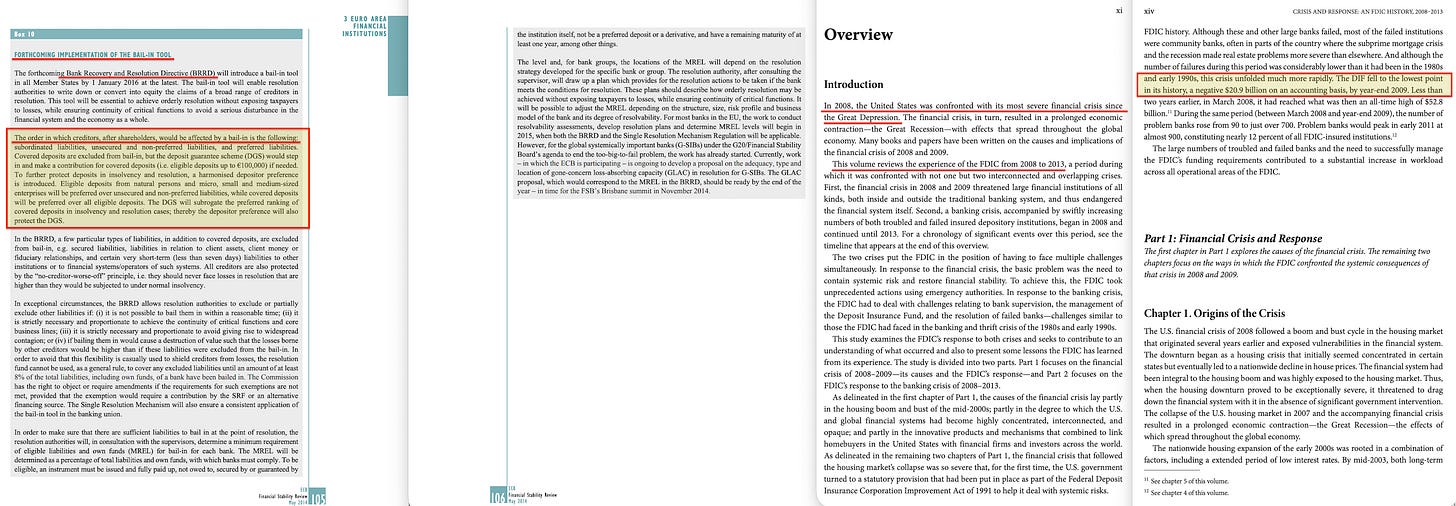

Modern bank resolution frameworks spell out the hierarchy. When a systemically important bank fails, losses are allocated in sequence4: shareholders get wiped out first, then various tiers of bonds and capital instruments, then senior unsecured creditors, then uninsured deposits from large corporations, then uninsured deposits from individuals and small businesses, and finally insured deposits.

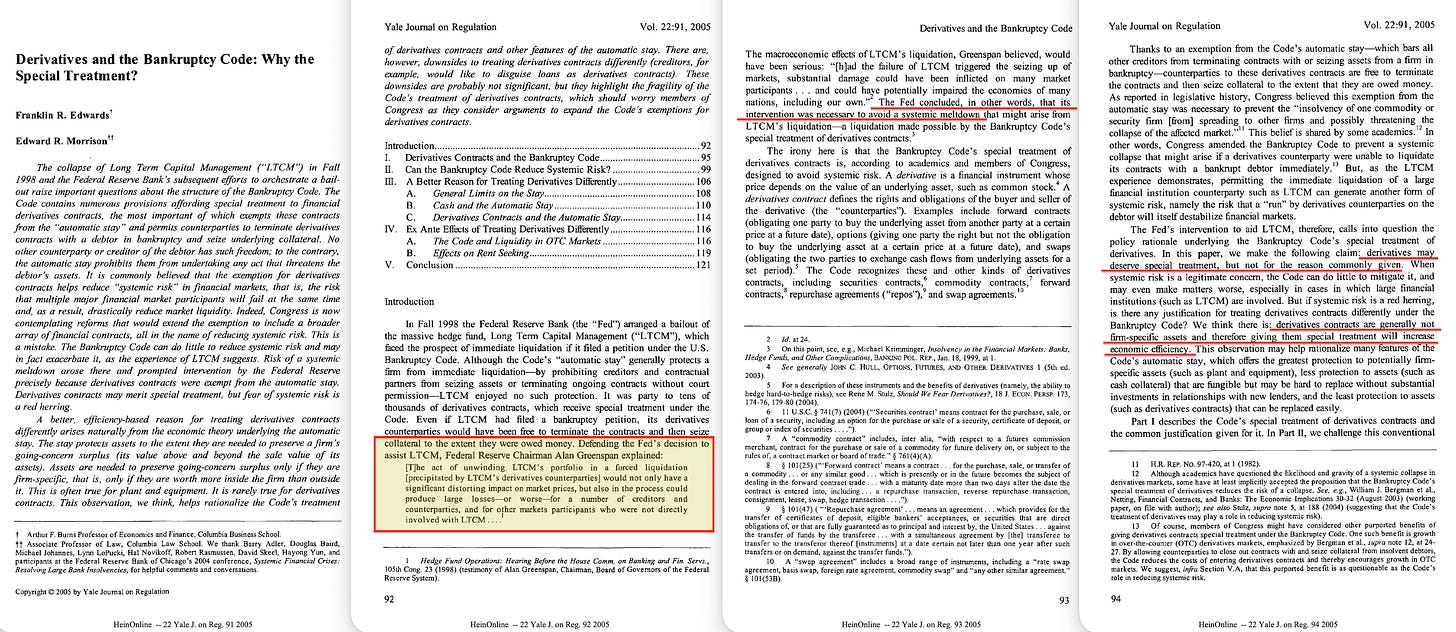

Derivatives counterparties occupy a special position outside this sequence: under safe harbour provisions in both British and American bankruptcy law, they can seize collateral and close out their positions before the normal process even begins5. The policy rationale is that letting derivatives unwind quickly prevents contagion spreading through the financial system. The practical result is that a bank’s trading positions rank ahead of your savings account.

In other words, the ‘efficiency’ argument is not about protecting depositors or ordinary customers. It’s about protecting the dealer network — the institutions on the other side of the derivatives book. The rule is justified as system stability, but its practical effect is priority: it creates a fast lane for large counterparties while everyone else — including you — waits in the normal queue.

The bail-in framework

After the 2008 financial crisis6, the G20 decided that taxpayer-funded bailouts had become politically toxic7. The alternative they chose was the bail-in8: instead of injecting public money to save a bank, authorities would recapitalise the failing institution by imposing losses on its shareholders and creditors.

The framework was coordinated internationally through the Financial Stability Board’s Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes9, first published in 2011 and updated in 2014. It became law through the EU Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive10, amendments to the UK Banking Act 200911, and Title II of the US Dodd-Frank Act12.

A joint paper published by the FDIC and the Bank of England in 2012, titled ‘Resolving Globally Active, Systemically Important Financial Institutions’13, put it plainly: losses would fall on shareholders and unsecured creditors.

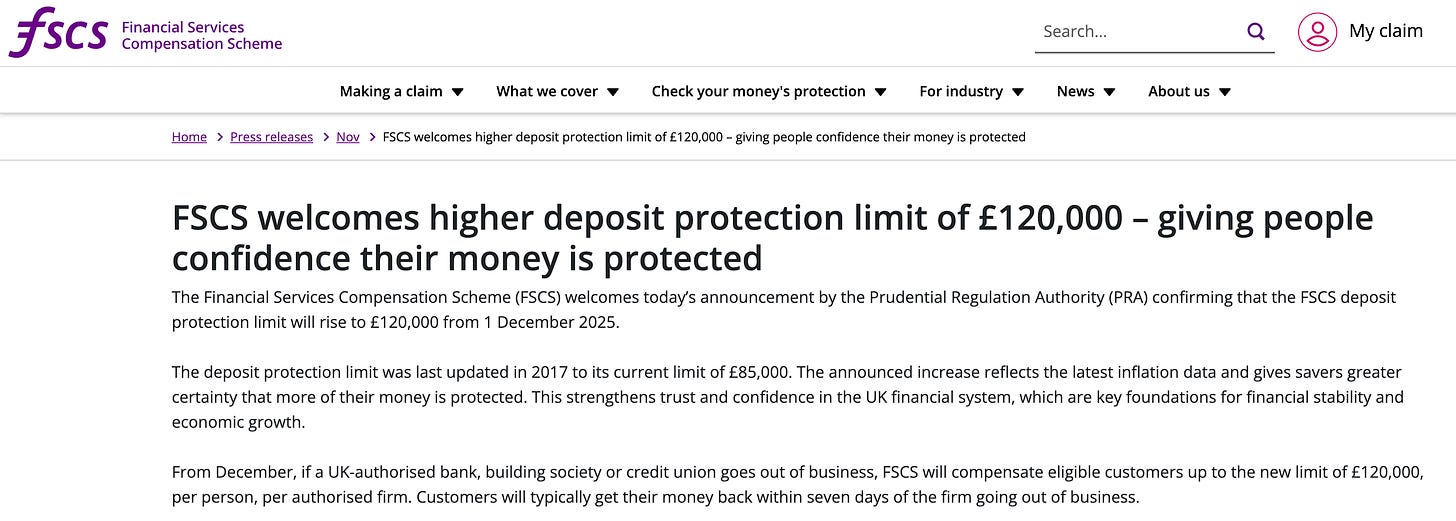

Depositors are unsecured creditors of the bank. In the UK, the FSCS covers deposits only up to £120,000 per eligible person per authorised firm14; balances above that cap are uninsured and therefore exposed to loss.

The powers granted to resolution authorities under these laws are sweeping and do not require a judge. They can seize control of a failing bank and fire its management, transfer assets and operations to a bridge bank, impose stays that prevent counterparties from terminating their contracts and withdrawing funds, write down the value of unsecured liabilities, and convert those liabilities into equity.

No trial, no vote among creditors. Judicial review, where the law allows it at all, happens after the fact.

Here is how it would work in practice. On a Friday evening after markets close, the resolution authority takes control. A stay prevents depositors and other creditors from withdrawing. The authority calculates how much capital the bank needs to survive, writes down claims in order of the hierarchy until that amount has been absorbed, converts remaining claims into shares in a restructured institution, and reopens the bank on Monday morning under new ownership15.

The depositor who went to bed on Friday believing they had cash wakes up on Monday holding equity in a bank they never chose to invest in. Their money has been used to absorb losses that would otherwise have fallen on bondholders or taxpayers.

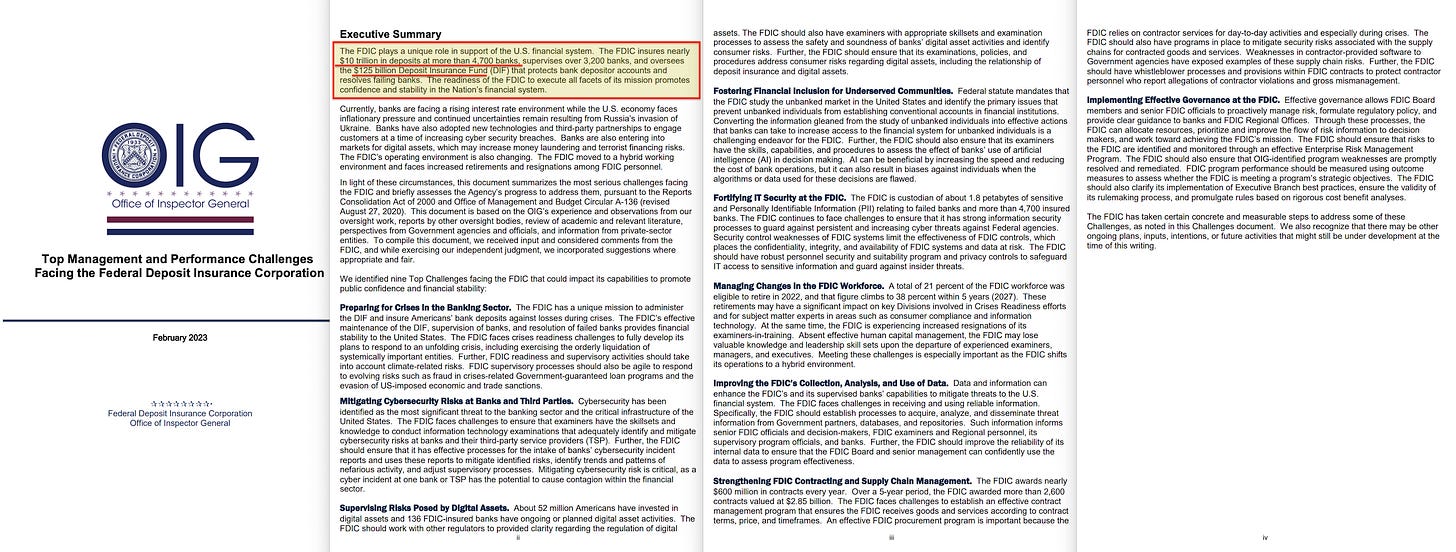

Deposit insurance schemes offer some protection, but the maths do not work in a systemic crisis. The FDIC holds roughly $125 billion in its insurance fund against roughly $10 trillion in total US deposits (2023)16 — coverage of around one percent. The FSCS faces similar numbers. In 2009, the FDIC's fund went negative to the tune of $21 billion17; it was only the implicit Treasury backstop that kept depositors whole.

These funds exist for isolated bank failures, where the rest of the system stays healthy enough to absorb the shock.

If multiple major institutions fail at the same time, the insurance runs out almost immediately, and even insured depositors find themselves holding claims in the resolution queue.

The same pattern in securities

When you buy shares through a broker, you probably believe you own specific securities held in your account. The legal reality is more complicated. Since the 1970s, most securities in the United States have been held through a central depository: the Depository Trust Company18 (DTC) holds the actual securities, and its nominee Cede & Co19 is the registered owner on the books of the issuing companies20.

Your broker has an account at the DTC, and you have an account with your broker. What you actually own is not specific shares but a ‘security entitlement’ — a bundle of contractual rights against your broker, giving you a claim to whatever quantity of that security your broker holds in an unallocated, pooled structure.

The 1994 revision of Article 8 of the Uniform Commercial Code21, drafted by the American Law Institute and the Uniform Law Commission, locked this arrangement into law. The revised Article 8 distinguishes between direct holding, where an investor owns specific identified securities, and indirect holding, where an investor owns a claim against an intermediary. Almost all retail investors, and most institutional investors, now hold indirect claims.

The implications in insolvency mirror those of bank deposits.

If your broker fails, you are not asserting a property right to specific securities that can be pulled out of the wreckage. You assert a contractual claim, and you share with other claimants in whatever remains after secured creditors have taken their cut.

The Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 200522 gave derivatives counterparties super-priority status23, letting them seize collateral from a failing institution without going through bankruptcy proceedings at all. In a crisis severe enough to threaten the central clearing infrastructure, the collateral pool backing derivatives exposures includes the securities nominally held for people like you through the DTC.

David Rogers Webb, a former hedge fund manager, laid out this architecture in his 2023 book The Great Taking2425. He points out that the DTCC holds roughly $3.5 billion in capital against a securities pool measured in tens of trillions of dollars, and argues that this undercapitalisation is a feature rather than a bug: the system is built so that in a severe enough crisis, secured creditors can sweep the collateral pool before beneficial owners see a penny.

Whether you accept his full thesis or not, the underlying legal mechanics are not in dispute. Most investors hold entitlements rather than property, and entitlements get paid according to a hierarchy where retail investors do not come first.

The same priority logic — private takes senior, public absorbs first losses — is being replicated in climate and development finance under the label ‘blended finance’.

From possession to control

Digitisation creates a problem for legal systems built around possession. You can possess a gold coin or a paper share certificate in a way that the law recognises and protects. You cannot possess an electronic record in the same way. The record exists as data on a system run by someone else, and your relationship to it depends entirely on what that system lets you do.

Commercial law has dealt with this by swapping possession for control. If you can enjoy the benefit of an electronic record, stop others from enjoying it, and transfer it to someone else, you have control — and control now counts as the legal equivalent of ownership.

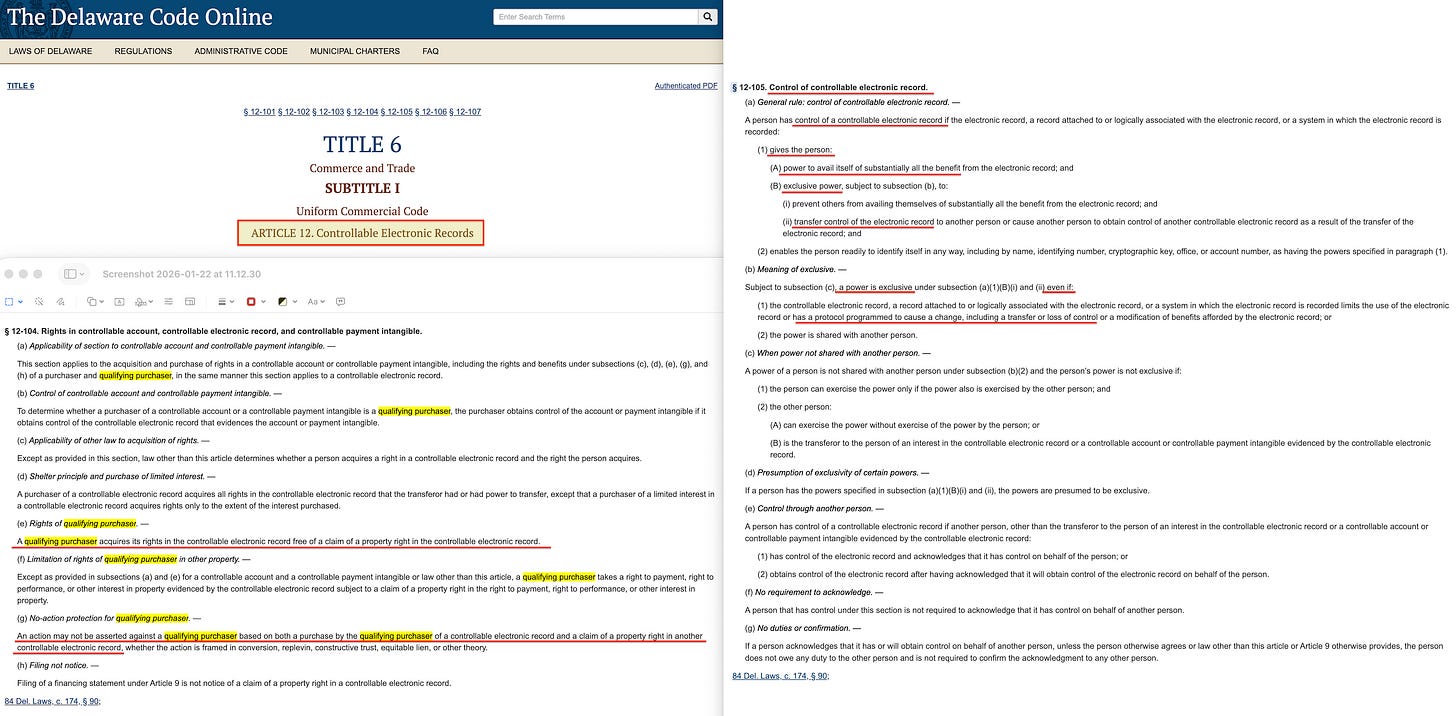

This idea first appeared in the 1994 revision of UCC Article 8, applied to indirectly held securities26. It spread to electronic chattel paper in the 1998 revision of Article 927. And in 2022, it was extended to all digital assets through Article 12, which covers what the drafters called ‘controllable electronic records’28.

The definition is functional: you have control if the system gives you certain powers. The flip side is that if the system takes those powers away, you have lost control, and losing control now means losing the ownership claim that goes with it. The asset still exists, but your claim of ownership no longer follows it.

Article 12 also creates the ‘qualifying purchaser’ rule. Someone who gets control of a digital asset for value, in good faith, and without knowing about competing claims takes the asset free of those claims. In a bank resolution: when an authority takes control of assets using statutory powers, they have taken control for value (the equity conversion counts) and in good faith (they are doing what the law tells them to).

Your prior claim becomes an ‘adverse claim’, and the statute wipes it out. You cannot sue to get the asset back because the law says your claim does not follow it.

Taking control global

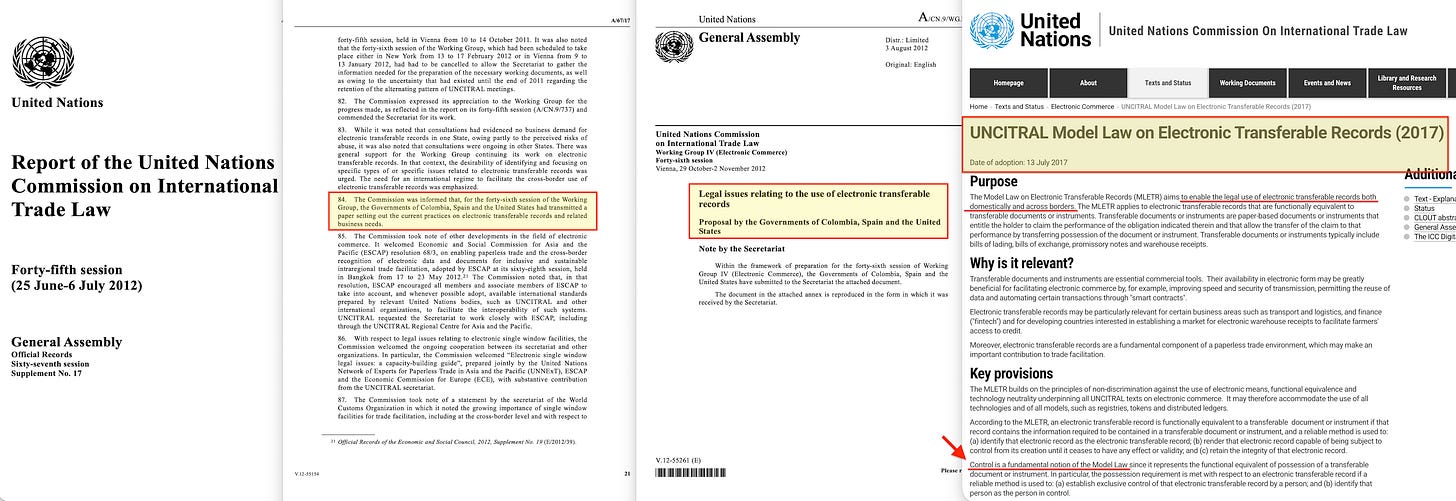

The control concept was invented in the United States by two private bodies: the American Law Institute and the Uniform Law Commission. It did not stay American.

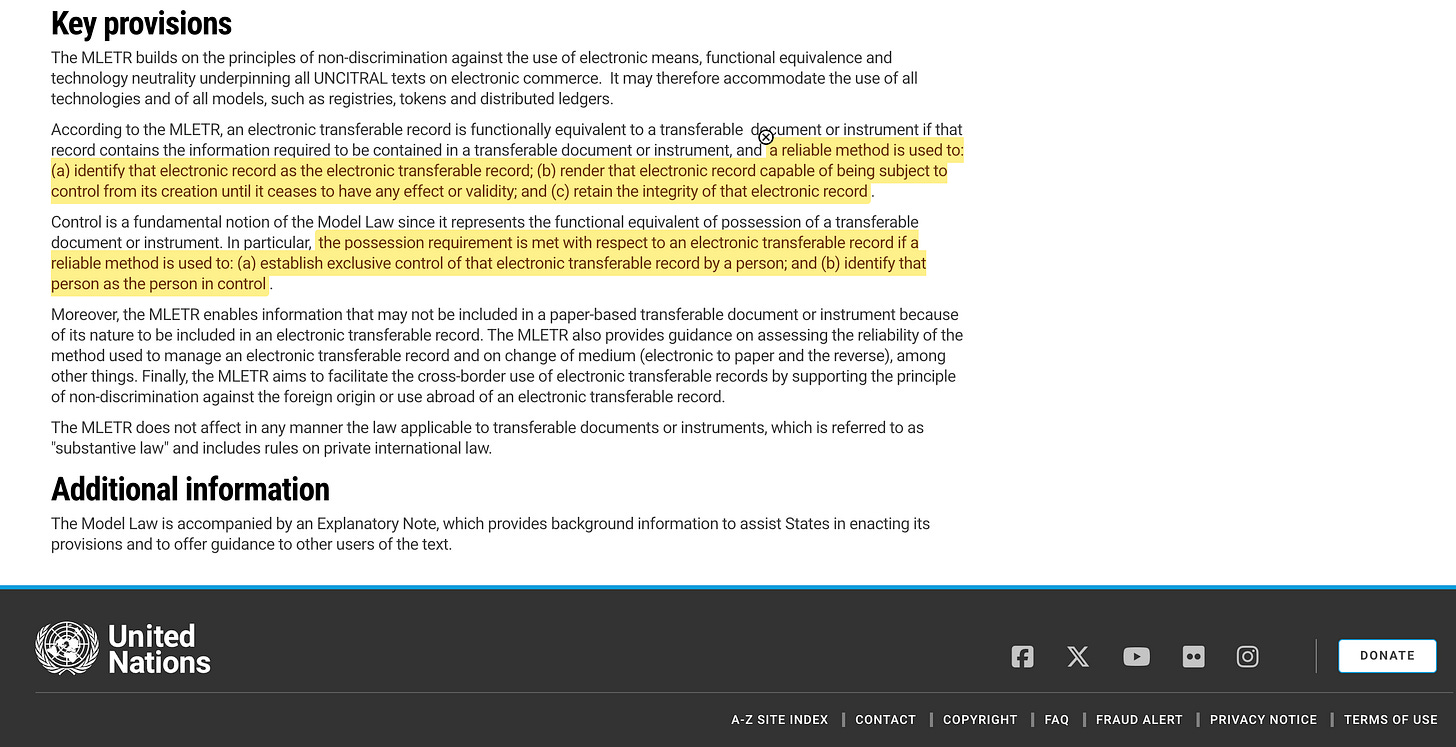

In 2011, the governments of Colombia, Spain, and the United States submitted a joint proposal to UNCITRAL Working Group IV29, the United Nations body that develops international trade law. The proposal, documented as A/CN.9/WG.IV/WP.119, dealt with ‘legal issues relating to the use of electronic transferable records’30. Over six years, the Working Group turned it into the Model Law on Electronic Transferable Records (MLETR), adopted in 201731.

MLETR takes the control concept from American commercial law and makes it the global standard for electronic trade documents and transferable records. Under the Model Law, an electronic record counts as legally equivalent to a paper document only if a ‘reliable method’ shows that an identifiable person has exclusive control.

That phrase ‘reliable method’ hands power to a gatekeeper. The law does not say which technologies or systems qualify. Regulators in each country decide that, and regulators will naturally approve the systems they run or supervise — central bank systems and systems that plug into them.

Assets held through systems that regulators do not bless may have uncertain legal status. The framework does not outlaw alternatives; it just refuses to recognise them.

The International Chamber of Commerce, through its Digital Standards Initiative32, has become the main promoter of MLETR adoption worldwide33. The G7 endorsed the Model Law at Carbis Bay in 202134. The United Kingdom passed it into law through the Electronic Trade Documents Act 202335. Singapore amended its Electronic Transactions Act in 202136. France, Germany, and Japan have legislation in the works. The ICC runs adoption programmes in dozens of countries across Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, and the Pacific37.

The result is a globally harmonised legal framework where ownership of electronic records depends on system-defined control. Different parliaments pass different laws in different years, but they all put the same concept into effect.

The person the system recognises as having control is effectively the owner. The person the system does not recognise has an adverse claim that will not stand up against a qualifying purchaser.

The institutional geography

The harmonisation of financial regulation and commercial law across countries does not happen by accident. It is coordinated through a specific set of institutions, and understanding how they connect shows why separate legal changes in different countries produce the same outcomes.

The Bank for International Settlements, founded in Basel in 1930 on a model proposed by the economist Julius Wolf at the 1892 Brussels International Monetary Conference38, sits at the centre of global financial coordination.

This model is derived from the London Bankers Clearinghouse which placed the Bank of England at the apex; a system which Alfred de Rothschild at the 1892 conference called ‘perfect’.

The BIS calls itself the ‘central bank of central banks’, and it hosts several of the bodies behind the frameworks discussed in this article.

The Financial Stability Board, created by the G20 in 200939, wrote the Key Attributes that define the global bail-in framework. The FSB secretariat is physically located inside the BIS building in Basel. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, which sets the capital rules known as Basel III, operates under the BIS umbrella. The Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures, which coordinates payment system standards and links national systems together, is also a BIS committee.

The BIS Innovation Hub40, with centres in Hong Kong, Singapore, London, Stockholm, Toronto, and elsewhere, is building the technical plumbing for central bank digital currencies and tokenised settlement.

Legal harmonisation runs through different channels but serves the same architecture. UNCITRAL in Vienna drafts the model laws41. The Uniform Law Commission42 and American Law Institute43 in Chicago and Philadelphia draft the UCC amendments. The FATF sets anti-money laundering standards that define access to the system44, now with even ‘financial inclusion’ on its remit45 (onboarding those outside the control structure, typically ‘underserved’ people in developing nations).

The ICC in Paris pushes for adoption. The G7 and G20 provide political cover. National parliaments pass the laws.

The letterheads differ. The outcomes converge.

The technical infrastructure

The BIS has described its ‘unified ledger’46 — a shared programmable platform where central bank digital currencies, tokenised commercial bank deposits, and tokenised assets — securities, bonds, likely property — coexist and settle atomically.

That vision is being built through a series of Innovation Hub47 projects. Project mBridge48 handles wholesale central bank digital currency settlement across borders and reached minimum viable product status in 2024 before being handed to participating central banks to run. Project Nexus49 links domestic instant payment systems internationally and went live in 2024. Project Rosalind50 built the API layer connecting private sector applications to central bank ledger infrastructure — enabling payment conditionality.

Project Mandala51 is building an automated compliance engine that bakes regulatory rules into transaction processing, so that transactions which break those rules simply cannot settle. Project Aurora52 applies machine learning to spot unusual patterns in transaction data.

These systems are designed to talk to each other through common data standards, particularly ISO 2002253, a messaging format that carries not just payment amounts but metadata describing the purpose of the transaction, where it came from, and its compliance status.

The projects were developed separately in different countries, which meant they avoided the scrutiny that a single announced ‘global central bank digital currency on a unified ledger including all tokenised assets’ would have attracted.

They share standards precisely so they can plug together.

Meanwhile, UNCITRAL Working Group IV is developing a Model Law on Identity Management and Trust Services54. Control over assets requires knowing who is exercising control.

The ledger must know who you are.

Programmable money

Central bank digital currencies differ from both physical cash and bank deposits in one crucial respect: they can carry rules that restrict how they may be used.

A banknote does not know where it has been or where it is going. Once you hold it, you can spend it on anything — legal or not — give it to anyone, or even keep it forever. A digital token on a central bank ledger can be programmed with conditions: an expiry date after which it becomes worthless if not spent, geographic limits on where it can be used, restrictions on what it can buy, caps on how much can move in a given period, or blocks on transfers to certain addresses.

The same infrastructure that enables instant settlement enables instant enforcement of these conditions. The unified ledger does not just make payments faster. It makes restrictions on payments enforceable at the moment you try to transact, before settlement happens, with no way to get around them.

Whether such restrictions will be imposed is a policy question that different countries will answer differently. That they can be imposed is a technical fact built into the architecture.

What this means in practice

Consider what happens when you put these pieces together.

Your bank deposit is legally a claim against the bank, not property in your possession. Resolution frameworks give authorities administrative power to write down that claim or convert it to equity without your consent and without going to court. Your securities are not property you own but contractual entitlements against intermediaries who hold everything in a pooled structure where secured creditors have priority during a time of crisis.

Digital assets — including CBDCs, tokenised securities, deposits, and potentially property — are governed by a legal framework where ownership means system-recognised control, and losing control means losing ownership. The systems that grant or deny control are run by or supervised by central banks. Those central banks are building infrastructure that settles transactions atomically and can embed compliance rules that stop non-qualifying transactions from going through at all.

In the paper-based systems that came before, taking assets required physical action: seizing documents, freezing accounts through manual processes, getting court orders, serving notices. These steps were slow, and the slowness was not just inefficient — it gave people time to to fight back. The friction was protective.

The new architecture treats that friction as delay to be engineered out. The language around these developments talks about efficiency, modernisation, resilience, and financial stability. And there is a reasonable regulatory view that instant resolution capability genuinely does protect the financial system from the kind of chaotic collapse that followed Lehman Brothers in 200855.

But efficiency for the system is exposure for the individual inside it. The same capability that lets authorities stabilise a failing bank quickly lets them take depositor assets quickly. The same legal framework that gives commercial certainty for transactions in electronic records guarantees that your claim gets wiped out when control passes to a qualifying purchaser.

This is the architecture that will be in place when the next crisis hits. Not paper records that take days to seize, but tokenised claims that can be rewritten in microseconds with no possibility of appeal. The question is not whether the tools will be used, but how fast — and against whom.

Then comes the crisis.

Conclusion

Look, none of this is some brand-new ‘conspiracy’. It’s been building for well over a century.

1892 (Julius Wolf, Brussels): park assets inside a central institution (gold in central bank vaults, in his case), and let people trade claims (receipts) against the pool while the institution keeps control of the underlying assets.

1930 (BIS): the model scales up into the ‘central bank of central banks’.

1970s (DTCC/CeDe): securities settlement gets rebuilt around the same pooled-claim structure.

2005 (BAPCPA): the derivatives ‘safe harbour’ gets expanded — big counterparties can unwind and enforce collateral immediately, while everyone else is stuck in the slower lane.

Post-2008 (resolution regimes): authorities get the power to restructure banks over a weekend; covered deposits are protected up to the cap, uninsured balances sit in the hierarchy.

2017- (MLETR): the principle goes global: for electronic records, ‘ownership’ boils down to who the system recognises as having control.

In simple terms: you don’t own the underlying asset — you own a claim. In a crisis, the big players move first, and everyone else waits in line, hoping there’s still something left.

The asset might be yours on paper. But in a crisis, it’s whoever the system says controls it. And the system carries out its verdict in a microsecond with no possibility of appeal.

The trick hasn’t changed. What’s changed is the speed.

Gold used to take weeks to move. Share trades went from T+5 to T+3 to T+2 to T+1. What’s being built now settles instantly — atomically and irreversibly — faster than any human review, legal challenge, or political pushback can keep up with.

And in a real crisis, as large banks fail, the story likely won’t be ‘markets recover’, but ‘assets get pulled toward the only backstop left: the central banks’.

Resolution rules let authorities transfer assets and liabilities into bridge structures and rewrite claims over a weekend — no court drama required. Central banks step in as lender of last resort to keep the game going, but only against collateral they control, on their terms. Tokenisation tightens the loop: if ‘ownership’ is basically whatever the system recognises as ‘control’, then whoever runs the settlement layer can freeze, transfer, net, or swap positions at software speed.

That’s what ‘financial stability’ means in practice: private balance sheets blow up, and the central bank balance sheet becomes the warehouse that ends up holding — and controlling — the clean assets.

The 1980s Latin American debt crisis is a good reality check. The major American banks were sitting on roughly $500 billion of underperforming LatAm56 debt57, realistically worth around 20 cents on the dollar, and backed by only about $150 billion of net equity. That’s the whole problem in two numbers.

If they’d taken the losses, Wall Street would have crashed.

So they didn’t. They slowed the clock — rollovers, restructurings, regulatory ‘forbearance’ — anything to stop the losses landing all at once. The S&L crisis kept public attention elsewhere58. And it wasn’t just delay. There were backdoor bailouts too: ‘debt relief’ packages that looked like forgiveness for the countries, but in practice helped make the banks mostly whole, by repackaging the loans and leaning on the taxpayer.

Now imagine the same kind of imbalance again, but this time on tokenised rails. When it breaks, it breaks fast — possibly even in microseconds, while you’re asleep. Collateral is grabbed first, claims are rewritten, and the only thing that keeps payments and settlement running is the central bank stepping in. But that support isn’t charity — it comes with strings: collateral, control, and terms set at the top. That’s the punchline.

In a crisis, the system doesn’t protect your claim; it protects the core. And the way it does that is by pulling assets up to the backstop.

And that backstop is the central bank.

Find me on Telegram: https://t.me/escapekey

Find me on Gettr: https://gettr.com/user/escapekey

Bitcoin 33ZTTSBND1Pv3YCFUk2NpkCEQmNFopxj5C

Ethereum 0x1fe599E8b580bab6DDD9Fa502CcE3330d033c63c

Perfect timing you have Esc Key.

I have been educating on The Going Direct Reset since 2021. I didn't read The Great Taking until last year and it was the catalyst for me. I've done a lot of research that supported what David Rogers Webb said.

Beyond the Great Taking, we have The Globalist Purge (Archive.org; 3 part series). Other substacks have been discussing the mass population control and logistical infrastructure arrangements commentors have seen.

The hit piece/psyop "Sovereign" by Universal Studios lies from end to end about the Sovereign Citizen movement in the USA. People here want OUT, and are trying very hard to figure out how to do it. The so called Silent Majority in the USA is now having kids outside of the system, not enrolling them in Social Security, schools, etc. No greedy, murderous pediatricians killing their newborns with SIDS for a few more shekels. One of the Sovereign Citizen participants told me that the DOJ has declared the Sovereign Citizen movement to be the #1 terrorist organization... That an entire, grossly inaccurate, big budget movie was made about it seems to support that, but I have to verify.

The cognitive dissonance introduced by the billionare controlled US administration laying claim to Greenland and Canada is MASSIVE. Nobody (with an intact and fully functioning brain) in the USA wants to impinge on any other country's sovereignty. Nobody on any side.

I recently read The Great Taking and this article really brings it into focus - much more clear and succinct. Thank You. After reading The Great Taking I asked ChatGPT whether the thesis of the book was accurate. The answer was emphatically No, only securities that have been contractually and specifically committed as collateral(ie, debt collateral) would be subject to any type of “clearing sweep” after an insolvency. Chat pointed to the FDIC as protective of ordinary depositors but admitted the reserve limitation(1-2%). Chat clearly showed its programming limitations and inability to think.

So they have done the same thing to our money that they did to our bodies during Covid(and they are still doing). Legal legerdemain, secrecy and emergency engineering allow the powers that be to do whatever they want to us, all in violation of our rights and against all principles of democratic government, due process and Constituituonal law. We must wake up and shake our brain fog or it will very soon be too late.