Own nothing. Control everything.

A phrase commonly attributed to both Rothschild and Rockefeller.

Now, let me tell you how they’ve almost managed to pull it off.

Contemporary global governance focuses on a few key strategies. We have the key objective of ‘subsidiarity’, which in short describes how everything should be ‘decentralised to the lowest appropriate extent’. Trouble, however, is — to what extent is appropriate when it comes to alleged global matters?

Subsidiarity describes distributing responsibility along the hierarchical structure. Global matters (United Nations) supercede regional (such as the EU, or United Kingdom), which in turn supercede national (France as part of the EU, or Scotland as part of the UK), followed by area/state, and then local. Sure, they tell you that all ‘decision-making’ is ‘decentralised’, but should you go against the grain, the ‘decision-taking’ conveniently is controlled top-down, meaning all decisions can be overridden by those above in the hierarchy — though they’ll claim this is due to ‘the best available scientific consensus’ which conveniently was only recently updated.

Beyond structural hierarchy lies the question of governance type itself. And this governance type — call it the Third Way, the Third System, the New Economic Policy, the Trisectoral Network… Fabian guild socialism, tripartite governance, corporatism… it really does not matter one bit. It’s all the same. And it was brought in through the United Nations system via Agenda 21, and it fundamentally revolves around a public-private-partnership for the common good. It’s just a matter who gets to define what the common good is. But in contemporary settings, we’re speaking of Civil Society Organisations or General Consultative Status NGOs — entirely outside democratic capacity.

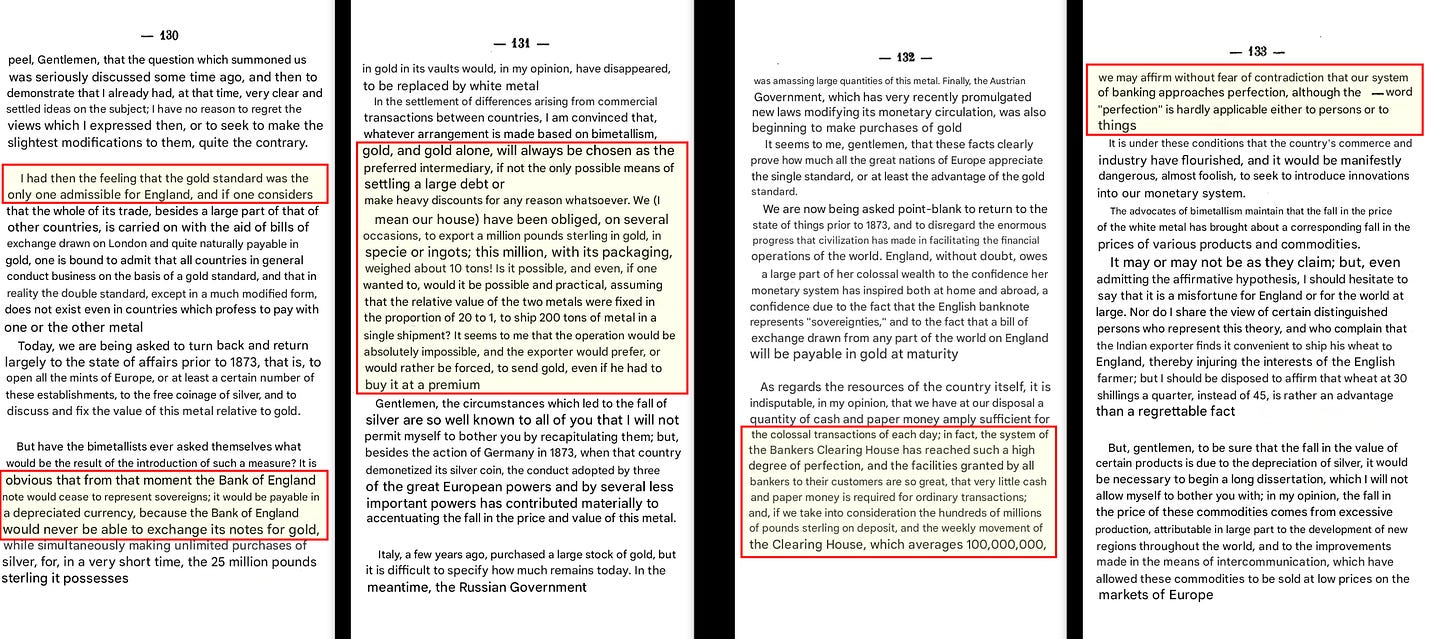

In a more contemporary setting, we hear much talk of Inclusive Capitalism. This revolves around the Marxist revisionist Eduard Bernstein's 1899 application of Julius Wolf's 1892 international gold-clearance settlement function, which landed in the BIS upon its founding. See, while Wolf described a public-private partnership which centres around units of currency with an associated international clearing function, Eduard Bernstein reframed this mechanism around social justice, and thus fundamentally — ethics.

What Bernstein described was public-private cooperation for the common good, almost exactly what Tony Blair described in his 1991 article in Marxism Today (see: The Third Way).

At the time of the Bank for International Settlements' founding, the model they used was that outlined by Julius Wolf, though that's only part of the story. The real significance lies not in the hyper-convenient timing — the BIS being negotiated exactly as markets crashed in 1929 — but in what took place between 1892 and 1930, and more importantly, in the years leading up to Wolf's book

This is exceptionally important because the plan is a global coup d'état. Not just because of where we're heading via the Financial Stability Board, with the Fabians' In Tandem being particularly problematic, but because of how we got here.

The third aspect of contemporary global governance relates to cosmopolitanism, which can be broadly understood through the lens of contemporary Western leaders, who appear to care less about their own citizens, as opposed to those terribly marginalised people who illegally crossed the channel and are now put in five-star hotels at taxpayer expense1 — while retirees who spent their lives paying into the system now see their benefits cut2.

Cosmopolitanism, thus, means living in adherence to whatever Eduard Bernstein decides is the global, common good. Consequently, the three combined relate to the hierarchical structure, the governance mechanism, and the expected, passive obedience by the people. And these three mark almost exactly the spot of the Fabian Society. And that's certainly no coincidence, not least because Rosa Luxemburg and other hardline Marxists derogatorily described Bernstein as a 'German Fabian'3.

On May the 17th, 2005, the Bank for International Settlements celebrated4 the release of Gianni Toniola’s new book, Central Bank Cooperation at the Bank for International Settlements5. And though I’ve read a great deal of documents on the6 BIS7, that book is one I missed.

We skip to page 16, which sets the stage. The First World War led to the suspension of gold-backed currencies all over Europe. But the book quickly establishes that while WW1 was won through economic might as opposed to military, the United Kingdom was practically bankrupt by 1917:

In 1916, President Strong of the New York Fed spent almost three months in Europe, mostly between London and Paris, in order to establish formal agreements between the two central banks and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York for maintaining preferential accounts with each, for the purchasing of bills, and for the earmarking of gold.

Essentially, allocating gold for clearance — resonating directly with Wolf's proposal.

It was during Benjamin Strong's wartime visits to London that he established the close personal relationship with Montagu Norman then a member of the Court of the Bank of England, that was to provide intellectual leadership with regard to the development of central banking and lead to some practical cooperative results in currency stabilisation.

This is particularly significant because it was Benjamin Strong and Montagu Norman who were in charge of their respective central banks during the 1929 BIS negotiations (see Black Tuesday above).

It was in the immediate postwar period that Norman’s ideas about the role of central banks in restoring a viable monetary system received wide attention and that earlier proposals about the establishment of an international bank tound their way into official documents

To remind, it was Julius Wolf who suggested the conceptual mechanism in 1892. However, before we get there:

Whatever the relative weight of the advantages and disadvantages of floating rates, the majority of European public opinion regarded them as an unmitigated disaster.

That, for instance, is not what contemporary economic history will tell you. In fact, contemporary books will typically tell you that the gold standard was a disaster. Either way, what the insiders were angling for, was a return to the London-centric financial system which existed before the war.

… the position ol Keynes, Hawtrey, Cassell, and others who recommended fixing the new gold parties at levels consistent with the current purchasing power of each national currency…

And that is also noteworthy. Because if you read contemporary literature, it will tell you one thing beyond all: Keynes was a major opponent and vocal critic of the gold standard, though personally, I think he was an opportunist, with ulterior motives.

And it carries on by detailing that central bankers along with private bankers played a major part in post-war negotiations, adding:

Early in 1921, Norman issued a kind of central bank manifesto… Norman stressed independence from national governments.

Again, that's news to me. But let's finish this document before addressing this.

As for Wolf…

Luigi Luzzatti, a Venetian and a prominent Italian political figure, is largely credited with developing in 1907 the first ideas about an international body for central bank cooperation. In fact, the issue had been on the agenda since the International Monetary Conference of 1881, and in 1892 Julius Wolff, a professor at the University of Breslau, submitted at the Brussels International Monetary Conference a project for the creation of an international currency, to be used for emergency lending to central banks, backed by gold reserves contributed by the central banks themselves and to be issued by a joint institution based in a neutral country.

Et voila. Confirmation. We’re back to Julius Wolf again, though implemented through Luigi Luzzatti8. And what I find interesting in that regard, more than anything, is the year. See, this was the year of the Second Hague Peace Conference9, which very much fused ethical values into peace affairs.

But Luzzatti pushed Wolf's idea to its logical conclusion:

Rather than being occasional and dictated by extreme emergencies, Luzzatti argued, lending amongst monetary authorities should become the norm. An international commission endowed with ‘fiduciary powers’ should coordinate action for the achievement of international monetary peace.

Which, of course, came through the BIS…

Several of the ideas developed before the Great War resurfaced at the 1920 Brussels Economic Conference… Frank Vanderlip, former president of the National City Bank, suggested reorganising the European central banks following the model of the Federal Reserve System in the United States.

… which Vanderlip suggested should follow the model of the Federal Reserve.

… the Financial Commission also passed a resolution - apparently inspired by Hawtrey. Keynes, and Home - reccommending the creation of an association or permanent understanding for cooperation amongst central banks, not necessarily limited to Europe, to coordinate credit policies… the commission called for a conference of central bankers and also suggested its agenda…

Keynes himself served as an inspiration? That's interesting, not least because beyond being a major architect of the financial system, he — along with Leonard S Woolf10 — was also a prominent member of the Cambridge Apostles, whose membership in the early 1930s was almost exclusively composed of scientific socialists, including members of the Cambridge Five spy ring11. And their favourite gathering spot just coincidentally happened to be Victor Rothschild’s flat in central London.

We could carry on with the report, but we have what we need. First, let's examine the Central Bank manifesto. Here it is — in Richard Sydney Sayers' 1976 book titled The Bank of England 1891-194412.

And it's certainly… familiar. Because it's not a million miles off what JP Morgan requested in that infamous cable, sent exactly as the markets crashed in 1929.

Here’s the link again so that you can check for yourself.

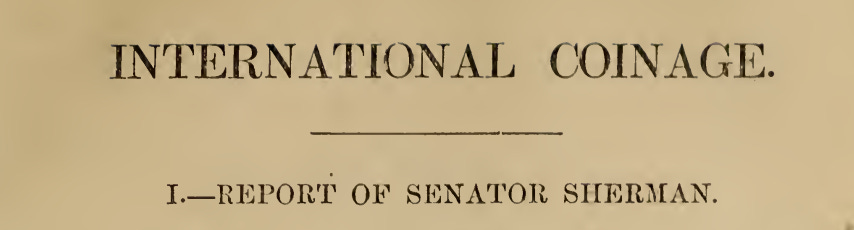

But there’s a second trail in the above document, and it’s the International Monetary Conferences13, with an interesting one from the first event to be found over here14.

See, in 1868, the U.S. Senate released a comprehensive report on international coinage, proposing a harmonised gold standard — not as some abstract utopia, but as a practical solution to frictionless exchange between nations. This wasn’t just about convenience, but about interoperability, clearing, and a shared system of measurement — a quasi-clearinghouse architecture. They even proposed that these coins — though nationally distinct — would be legal tender across borders.

And that somewhat sticks out, especially in light of the Bank Charter Act of 184415, which not only granted the Bank of England a monopoly on currency issuance, but also anchored that currency in gold. In other words, what the British centralised nationally, the Americans were suggesting to globalise — and this, crucially, at a time when the United States didn’t even have a central bank.

Most people today believe the gold standard to be a dusty economic relic. A shiny pet rock, and not much more. But historically, it served as a primary mechanism of financial control — clearance, settlement, and dependency.

A.P. Wooldridge16, speaking to the Texas Bankers' Association in 1898, claimed that gold emerged through 'natural selection' — like the electric light or the modern plough. His argument centres on the idea that all nations conveniently and simultaneously decided to adopt gold as their monetary standard. Meanwhile, Horace White — addressing the 1893 Congress of Bankers and Financiers in Chicago17 — detailed how England's supposedly 'natural' shift to gold was actually a response to monetary crises caused by rigged ratios between silver and gold.

But Baron von Kardorff-Wabnitz18, writing in 1880, warned that demonetising silver wouldn't merely change the currency. It would reduce liquidity, centralise control, and economically paralyse those outside the network. And that's precisely what took place. Silver was discarded not because it failed, but because it worked — and wasn't centrally controllable.

In digging through the most interesting documents, I located a healthy cache which — though fascinating — would make this post incredibly long should I cover them all. So let me instead link these for those who seek to investigate further on the 1881 conference 19202122232425, along with miscellaneous but contextually related material on currency, banking, and politics2627282930313233343536.

This allows us to focus on the primary event — the one taking place in 1892. But let's get a few other links from that event out of the way first373839. As a side note — a common conversation at the time related to bimetallic currencies, backed by not merely gold, but typically silver too40.

But the document we're looking for is the official proceedings from 1892, titled Le problème monétaire et la Conférence monétaire internationale de Bruxelles 41. As the document is written in French, I ran it through several translation services to ensure accuracy.

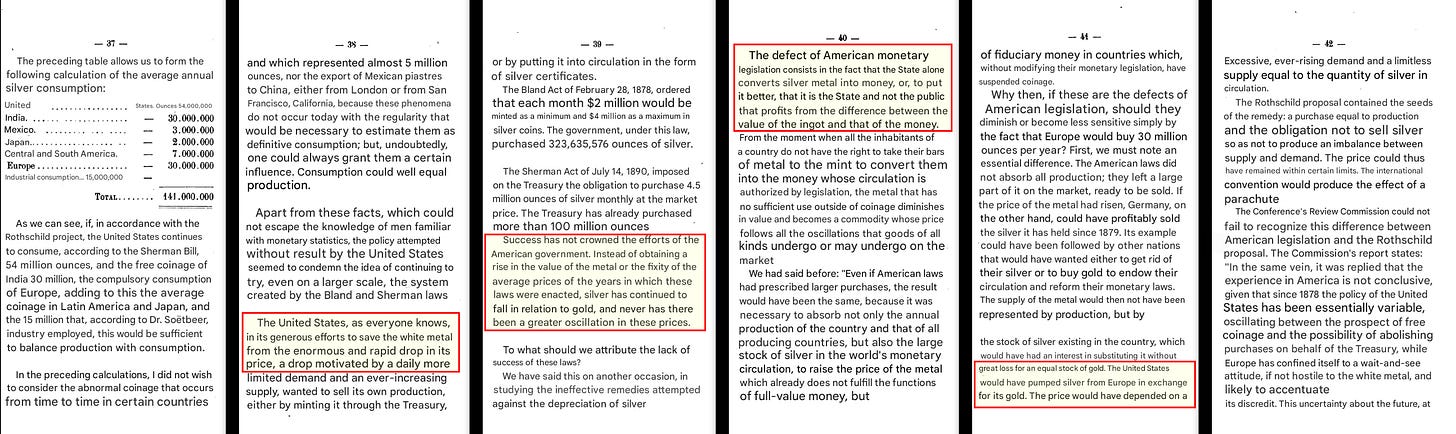

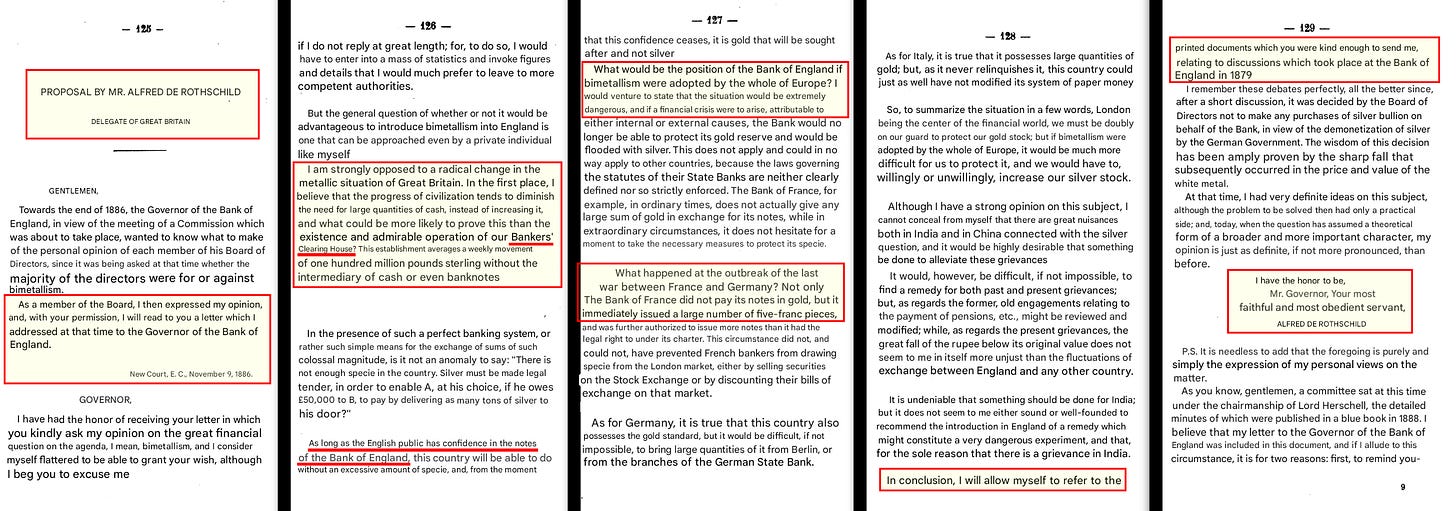

Chapter 3 outlines Alfred de Rothschild's suggested project, which was ultimately rejected. See, Rothschild was strongly in favour of a monometallic currency — in this case, gold.

The United States at the time used silver as currency. But as silver had suffered a collapse in prices, this naturally spilled into the value of the currency. To address this, the American government supported its currency by buying up vast quantities of silver for monetisation purposes. But to the shock of, well, no-one with a grain of economic sense, this didn't work. It certainly didn't have the desired effect of stabilising the currency.

But what was this proposal actually about? Well… it's a very interesting one. The proposal begins with Alfred de Rothschild42 including a paper of his own from 1886 (in his capacity as Director of the Bank of England) — incidentally, the exact year Wolf is supposed to have first spoken of his gold clearance idea — addressed to the governor of the Bank of England:

I am strongly opposed to a radical change in the metallic situation of Great Britain. In the first place, I believe that the progress of civilization tends to diminish the need for large quantities of cash, instead of increasing it, and what could be more likely to prove this than the existence and admirable operation of our Bankers' Clearing House? This establishment averages a weekly move of one hundred million pounds sterling without the intermediary of cash or even banknotes

That's… really interesting. A banker's clearinghouse?

He continues, describing the impossibility of introducing silver into the equation, before once again returning to the clearinghouse:

… in fact, the system of the Bankers Clearing House has reached such a high degree of perfection, and the facilities granted by all bankers to their customers are so great, that very little cash and paper money is required for ordinary transactions; and, if we take into consideration the hundreds of millions of pounds sterling on deposit, and the weekly movement of the Clearing House, which averages 100,000,000, we may affirm without fear of contradiction that our system of banking approaches perfection, although the word "perfection" is hardly applicable either to persons or to things

Incidentally, this clearinghouse is described by Alfred de Rothschild as nothing short of perfection itself!

Rothschild then turns to the American suggestion:

Setting aside all other considerations, it seems to me impossible to arrive at an international agreement on the question of a universal monetary circulation, since no two countries are alike in their wealth, their receipts, or their expenditures.

This could be accepted as a valid point. But it's equally self-serving, as the American suggestion centred on physical coinage, whereas Rothschild's solution involved paper certificates representing quantities of metal.

It took a few documents to locate a decent description of this system. But The London Banking and Bankers' Clearing House System43 by Ernest Seyd, in short, a fantastic source which describes it in detail. And given its pivotal status, it's probably fairly important we cover it properly.

In 19th-century Britain, the banking system evolved into a sophisticated, hierarchical architecture that supported both domestic commerce and global finance. At its base were thousands of local and regional banks serving individuals, farmers, and small businesses. Local banks were customer-facing, and at the end of the day, whatever they had taken in through cheques had to be netted with what they had paid out. And that differential would then be paid (or received) via accounts these banks held with larger, London Clearing House banks.

The London clearing banks formed the operational core of the British monetary system. As members of the Clearing House — limited to around two dozen — they settled vast volumes of cheques and bills, not only for their own clients but also on behalf of regional and merchant banks. These clearing banks, in turn, held settlement accounts with the Bank of England, which ensured balanced daily net positions across the system. Acting as wholesale liquidity hubs, the clearing banks coordinated the flow of funds and credit throughout the national economy.

Above this operational layer sat the merchant banks — houses like Rothschilds — firms which didn't engage in retail banking or clearing. Instead, they specialised in sovereign lending, trade finance, infrastructure investment, and the placement of international securities. Despite their global reach and financial clout, merchant banks relied on clearing banks for routine monetary settlement, maintaining accounts through which they moved funds and cleared obligations. Their detachment from day-to-day operations enabled them to focus on high-level financial diplomacy and capital coordination.

So by this point we have local banks and merchant banks, which both held accounts with clearing house banks. And clearing house banks in turn held accounts with the Bank of England.

This hierarchical arrangement allowed the British financial system to scale both nationally and globally without sacrificing stability. Local banks served the productive economy; clearing banks ensured systemic liquidity and payment integrity; and merchant banks projected British financial power abroad. Anchoring the structure, the Bank of England provided finality and institutional trust. The result was a system decentralised in operation but centralised in settlement — an architecture that underpinned Britain's dominance in global finance well into the twentieth century.

In other words — we have the Bank of England on top. Then we have the clearing house banks. And then we have the local banks. And operational functionality has been decentralised to the lowest appropriate extent? That's subsidiarity, in short.

So here we see subsidiarity in its original form. Each tier employed distributed responsibility, with authority exercised at the lowest competent level, and higher tiers intervening only for stabilisation and settlement. Distributed sovereignty designed to manage complexity without collapsing into outright centralisation — but with ultimate control flowing upward when needed. This system was fully operational by 1860-1870, with the Bank of England — established in 1694 — serving as the cornerstone of the entire British banking hierarchy. 40 years before the Fabian Socialists, Arthur Penty44 and GDH Cole4546, began writing about much the same principles, but in capacity of governance.

What made the model enduring wasn't just its technical efficiency, but its mediating institutions — clearing houses, correspondent relationships, and central bank accounts — that served as trust-based conduits between otherwise autonomous actors. These mechanisms foreshadowed today's 'mediator model' of governance, where state, market, and civil society get coordinated through stakeholder councils, public-private partnerships, and international standards bodies. Rather than impose control from above, these systems employ layered coordination — akin to guild socialism, corporatism, and contemporary SDG governance, where stakeholders 'balance' the system from within.

Julius Wolf’s 1892 Sozialismus und kapitalistische Gesellschaftsordnung47 offers an early articulation of subsidiarity at the global scale. His proposal for internationally issued, gold-backed certificates wasn't just monetary innovation — it was a blueprint for mediating between private capital and public need. Gold, in Wolf's vision, functioned not merely as a commodity but as an ethical constant: a universal measure of value capable of transcending national divisions. The certificates represented not just claims on bullion, but claims on the legitimacy of exchange itself, administered by supranational institutions accountable to both market logic and public oversight.

Wolf's framework anticipated later institutions like the IMF's Special Drawing Rights, the Bank for International Settlements, and contemporary ESG-aligned central banking — all claiming to balance capital mobility with regulatory and ethical coherence.

But Wolf's logic — layered, mediated, and functionally distributed — can trace both its intellectual and institutional lineage to the British banking system. Local, clearing, and central banks coordinated economic life through nested tiers of trust and responsibility, each level mediating the complexity below it.

Julius Wolf's 1892 proposal extended this model onto the international plane, offering an institutional framework for reconciling private capital with public need through ethical mediation via gold-backed certificates. This anticipated the recursive logic of today's global financial governance — where supranational coordination is grounded in shared standards and layered accountability. But Wolf's architecture wasn't original — it replicated exactly the logic of the British clearing system already operating under the Bank of England, where Alfred de Rothschild served as director.

This logic of layered mediation soon expanded beyond finance into law and politics through the Hague Conventions, which introduced voluntary international norms centred on ethical, humanitarian law. Wolf's approach was further institutionalised through the League of Nations and later the United Nations — both adopting nested sovereignty where states retained formal independence while delegating coordination functions to global secretariats, councils, and agencies. These institutions mirrored financial clearing banks: trusted intermediaries tasked with stabilising competing claims under shared procedural and ethical frameworks.

Eduard Bernstein's revisionist Marxism48 played a critical role in legitimising this shift. By reinterpreting socialism as gradual integration of capitalist structures into ethically responsive institutions, Bernstein offered the political philosophy that complemented Wolf's technical vision. Where Wolf proposed gold-backed certificates to mediate cross-border capital flows, Bernstein advocated embedding such mechanisms within a broader framework of social justice and moral accountability. Together, they outlined the foundation for a system where public and private cooperation could be harmonised for a shared purpose through layered mediation — all while claiming democratic legitimacy for a fundamentally undemocratic architecture.

Today, this architecture defines the operational logic of global governance. Institutions like the IMF, BIS, and United Nations don't govern through law, but through webs of algorithmic indicators49, certificates, and metrics — each serving as a proxy for ethical legitimacy50 and systemic balance. Authority flows through international standards, performance benchmarks, and multilateral agreements, shaped by expert stakeholders with democratic accountability nowhere in sight.

The 19th-century British banking structure was the prototype. Just as London's clearing banks intermediated between thousands of local institutions and the Bank of England, today's supranational bodies act as clearing mechanisms between national governments, global finance, and UN agencies. The Federal Reserve System follows the same pattern: primary dealers51 channel liquidity and policy between the Fed and the broader financial ecosystem — a hierarchical structure mirroring the layered subsidiarity of the British system. A system implemented after the 1907 panic, supposedly triggered by currency and gold hoarding52 — precisely the problem Wolf's gold receipt system promised to solve.

Julius Wolf's 1892 proposal internationalised this architecture, while Eduard Bernstein's ethical revisionism provided its moral justification. Together, they articulated the foundations of a post-sovereign regime: neither command-and-control nor laissez-faire, but an order of mediated, layered responsibility — without a hint of democratic principle in sight.

In its contemporary form, this architecture has converged into algorithmic governance. Global objectives — such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals — get translated into thousands of quantifiable indicators, continuously tracked and modelled through digital twin simulations of human and ecological systems. These real-time, cybernetic models feed into resilience frameworks, enabling policymakers to simulate crises, forecast systemic stresses, and adjust regulations preemptively across health, finance, environment, and infrastructure — all for Bernstein's promised public-private partnership for the common good. What began as layered financial mediation has evolved into a planetary feedback system, where governance gets driven less by public vote and more by the outputs of nested, technocratic simulations claiming to represent global equilibrium.

This model ceased being theoretical in 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic activated this infrastructure at scale: real-time dashboards, behavioural modelling, cross-border data pipelines, and outcome-based public-private governance — all operating largely outside traditional legal and democratic oversight. With the WHO Pandemic Treaty, this logic has been codified into binding international law: a cybernetic model of sovereignty where health security serves as the prototype for programmable, indicator-led governance. What once passed through clearinghouses now flows through algorithms — still mediated, still layered, but increasingly abstracted from the public in whose name it claims to act.

Inclusive Capitalism completes the arc. By embedding social justice, environmental stewardship, and ethical governance into the instruments of capital allocation, it enshrines Bernstein's revisionist ethic within a planetary framework. ESG ratings, SDG-linked bonds, and stakeholder governance mechanisms now function as levers of moral certification, binding private investment to public purpose. This convergence gets further developed through initiatives like the Fabian Society's In Tandem proposal, which explicitly calls for integration of fiscal and monetary policy via a new Economic Policy Coordinating Committee — a model that would transfer fiscal policy powers to the Bank of England, once again entirely outside democratic capacity.

In short, it's a coup d'état under the guise of a unified ethical-economic mandate. Wolf's gold-backed certificates have evolved into algorithmically scored financial instruments, while Bernstein's social democracy becomes the moral justification for total economic orchestration. The result is a post-sovereign regime where ethics, policy, and capital no longer merely interact — they coalesce into a single, cybernetic system of global moral governance.

And it all began with the London Bankers Clearing House, which settled through the Bank of England — the institution granted a currency monopoly in 1844, establishing the template the Federal Reserve would replicate in 1913. These two central banks, built on identical clearing house architecture, dominated the negotiations that created the Bank for International Settlements in 1930 — scaling their model to the global level just as markets conveniently collapsed.

But this model — stakeholder mediation masquerading as decentralisation — was systematically deployed across every domain. Julius Wolf pioneered it through international finance. Eduard Bernstein wrapped it in socialist ethics. Tobias Asser at the Hague Peace Conferences embedded it in international law. Leonard Woolf institutionalised it in international politics through International Government. Alfred Zimmern and Lionel Curtis architected it into global governance and international social justice through the Third British Empire. And Norbert Wiener made it computational through cybernetics.

Now digital infrastructure completes the circuit through 'computational ethics'53 — where complex human relations reduce to algorithmic scores. Your calculation determines your moral position: negative makes you the oppressor, positive the oppressed. No nuance, no context, no appeal. The eternal struggle of opposing forces, mediated by those who control the algorithm, who define the variables, who set the thresholds.

Every previous iteration required human intermediaries. This time, the mediation is automated, scaled, inescapable. Democracy was excluded by design from the start.

But beneath all of it — the clearing systems, the layered governance, the ethics by algorithm — lies deeper intellectual architecture. Hermann Cohen's neo-Kantian system of 'infinite mediation' provided the framework: a world where opposing forces never directly confront each other but get perpetually reconciled through abstract intermediaries. Paul Carus's 'Religion of Science'54 made this digestible by promising that ethics itself could become scientific — universal principles discoverable through reason, applicable across all cultures, measurable and manageable. No longer messy human values but clean mathematical functions.

And while Carus called for an integration of religion and science through ethics, Cohen saw no use for the former, instead seeing it as a channel of moral encoding55.

But not only should ethics per Carus relate to science — truth should further be viewed from the perspective of the eternal.

And that then prompts the question — who decides what is ‘eternal’?

Between philosophy and implementation lay Alexander Bogdanov's Tektology56 — the 'universal organisational science' conceptual front-runner of General Systems Theory, which showed how to operationalise this vision across any domain. Where Cohen provided infinite mediation and Carus promised scientific ethics, Bogdanov delivered the mechanics: dynamic equilibrium through continuous adaptation, systems maintaining themselves through perpetual adjustment. What we now call 'adaptive management'57 is this trinity made technocratic. Perpetual adjustment without resolution. Continuous monitoring through intermediary metrics. Feedback loops that never close, only iterate. The crisis never ends because the system is designed for permanent crisis management — with those who control the parameters of adaptation permanently positioned as indispensable mediators.

But Bogdanov in 1909 further delivered us empiriomonism58, which applied exactly the ‘eternal’ collectively-subjective perspective to scientific truth Paul Carus called for.

And for that he was booted from the Bolshevik Party he co-founded with Lenin in 190359. Lenin spotted that empiriomonism, in essence, embraces and extends materialist monism, which lies at the heart of Marxist ideology60.

It's not a coincidence. It's Cohen's vision made operational through Carus's scientific ethics, Bogdanov's organisational science and empiriomonistic perspective: permanent mediation without resolution, governance without democracy, ethics without politics. The clearing house doesn't just clear transactions — it creates systemic dependence on the clearer.

This is why the same three-tier clearing house structure replicates perfectly from Britain (Bank of England → clearing banks → local banks) to America (Federal Reserve → regional Fed banks → member banks) to the world (BIS → central banks → national systems). Each iteration scales up the identical architecture, each crisis perfectly timed to justify the next expansion. The 1907 panic created the 'need' for the Fed, implementing Wolf's solution to gold hoarding. The 1929 crash — negotiated during BIS formation — created the 'need' for international coordination. COVID activates the full algorithmic version.

A pattern later repeated through the Club of Rome, IIASA, IPCC and others leading to the digital age — meaning that this is an established template, rolled out repeatedly. In fact, we already examined it.

It’s Dialectics by Design.

And now we arrive at the logical endpoint: Inclusive Capitalism. Where every previous iteration required crisis to justify expansion, this final form needs no crisis — it IS the crisis. Climate, inequality, health, justice — all reframed as 'planetary boundaries' within an overarching 'meta-crisis' where every issue interconnects with every other, where solving one problem allegedly worsens another, where only perpetual mediation can maintain the balance. The meta-crisis can never be resolved because it's designed to be irreducible — a permanent state of emergency requiring permanent management. Each domain becomes a clearing function for a moral economy61 where every transaction must be ethically mediated, every investment must clear through ESG ratings, every corporate decision must settle against stakeholder capitalism's ledger.

Nine planetary boundaries create infinite vectors for intervention. The meta-crisis ensures the interventions never end.

Adaptive management as the total system.

Cohen promised a system of pure ethics, beyond the messiness of democratic politics. Carus made it scientific. Bogdanov made it organisational. Franz Boas made it culturally sensitive62, and Tabara developed that into a framework. The planetary boundaries made it urgent.

The meta-crisis will make it permanent.

Inclusive Capitalism delivers their collective vision: not just financial clearing, but moral clearing — where every human exchange must pass through ethical algorithms, every local variation must map to global standards, every crisis must feed the next crisis. Those who position themselves as mediators of 'the common good' intermediate everything, always one layer removed from accountability, never required to ask the common people what they think is good. The system adapts to everything except the possibility of its own dissolution.

The clearing house never owned the assets — it just controlled the clearing. The mediators own nothing — they control everything. That's the beauty of the model: no property to defend, no territory to protect, no accountability to enforce. Just pure control through pure process.

You'll own nothing because ownership requires clearing.

They'll be happy because they control the clearing.

And, sure, the claim will be that it was merely coincidence. But all but pure faith would accept that the same architectural template — subsidiarity through clearing house mediation — somehow spontaneously emerged across finance, law, politics, and ethics without coordination. And the same figures appear at every critical juncture: Rothschild directing the Bank of England when Wolf presents his clearing proposal; Strong and Norman orchestrating both wartime gold arrangements and BIS negotiations; Keynes inspiring central bank cooperation whilst positioning himself as gold standard opponent; Bernstein reframing Wolf's mechanism through social justice exactly as Fabians were developing stakeholder governance. The intellectual framework isn't coincidental either — Cohen's infinite mediation, Carus's scientific ethics, Bogdanov's organisational science all converging in the 1890s-1900s just as these institutional templates were being implemented. The pattern is too consistent, the timing too convenient, the outcomes too beneficial to the same interests.

Either we're witnessing the most improbable series of coincidences in institutional history, or this was planned. In fact, a fitting term here appears to be — Conscious Evolution.

The pattern is irrefutable: 130 years of system replication across finance, ethics, law, politics, systems theory63, and governance. When the same template (subsidiarity + mediation + crisis leverage) reappears across epochs with identical architects, 'coincidence' is a theological excuse.

Conscious evolution is the only framework that explains

Why the London Clearing House (1850s) and the BIS (1930) share identical operational DNA,

Why Bernstein's 'ethical socialism' (1899) and the UN's SDGs (2015) identically fuse morality with capital allocation,

Why every systemic crisis since 1907 has expanded, never reduced, centralised mediation.

And why Inclusive Capitalism is the ideological endpoint.

The central bankers made it operational. The stakeholder ‘capitalists’ made it total. The philosophers made it seem inevitable.

And that was the plan all along.