Lionel Curtis, Alfred Zimmern, Leonard Woolf, and John Maynard Keynes — these were the lead architects of the Third British Empire.

But they didn’t act alone.

They operated within a larger framework — an elite network spanning think tanks, ministries, and monetary institutions. The Royal Institute of International Affairs and the Council on Foreign Relations served as long-term strategy hubs, while the Fabian Society translated vision into domestic policy. Behind them all, a deeper structure emerged: the growing empire of central banks, coordinated not from London or Washington, but from Basel.

And then there’s the Cambridge Apostles…

Key people contributing to the development of the Third British Empire include:

Lionel Curtis – Institutional structure

Designed federation model; co-founded the RIIA.Alfred Zimmern – Moral-institutional logic

Framed empire as global duty; League of Nations architect.Leonard Woolf – Technocratic machinery

Blueprinted agency-based governance; Fabian executor.John Maynard Keynes – Economic operating system

Embedded fiscal/monetary coordination into global order.H.G. Wells – Mythmaking and futurism

Envisioned a world state led by planners and scientists.G.B. Shaw – Rhetoric and propaganda

Justified rational planning and elite moral authority.Bertrand Russell – Philosophy and epistemics

Advocated for rule by experts; scientific governance.

But several others deserve a mention:

Arnold Toynbee – Civilizational narrative

Historical legitimation of elite-led renewal.Julian Huxley – Evolutionary planning/ethics

UNESCO, PEP, eugenics, scientific globalism.Philip Kerr (Lord Lothian) – Round Table imperialism

Bridged imperial federalism and American globalism.Montagu Norman – Central bank governance

Co-founded the BIS; extended the Bank of England’s reach.Otto Niemeyer – Imperial fiscal control

Austerity missions to colonies; fiscal conditionality.Joseph Needham – Science & world systems

Global science governance; Sino-British synthesis.Ramsay Muir – Liberal imperialist ethics

Morally framed administrative empire.Geoffrey Crowther – Financial media & planning

Advocated managed capitalism; interface between elites and public.C.E.M. Joad – Moral philosophy and public ethics

Popularized scientific-ethical governance.

And we could carry on. Because once you start looking at the periphery, you realise there’s really rather a lot of overlap with other organisations we’ve previously discussed. The next batch of names practically nominates itself:

Max Nicholson (WWF, PEP), John Boyd Orr (UNFAO), J.D. Bernal (scientific socialism), J.B.S. Haldane (Marxist biologist), Hugh H. Smith (Rockefeller), Maurice Dobb (Marxist economist), Miriam Rothschild (IUCN), A.E. Margolis (Marxist engineer), and others.

And those not formally listed as founders were often the ones who supplied the blueprint. Bernal didn’t just theorise scientific socialism — he drafted the model that would later shape UNESCO, ICSU, and WAAS. Haldane and Dobb weren’t institution builders, but they defined the ideological architecture that UNESCO and UNCTAD would later adopt wholesale. Smith helped turn Rockefeller health grants into the operational backbone of what became WHO. Rothschild sat at the intersection of science, ecology, and elite philanthropy — helping normalise conservation biology as a technocratic imperative. And Margolis? He was less visible but no less formative, pushing Soviet-style systems planning into British engineering discourse just as Nicholson and Woolf were laying the groundwork for domestic technocracy.

And if those faces look familiar, it’s because they all contributed to the 1941 Science and World Order conference — which was, in essence, a promotional vehicle for scientific socialism. Its follow-up, the 1942 exchange Science and Ethics, was even more explicit: the goal was no longer just to plan the world materially, but to define its moral direction.

And there was overlap still with another network — one quietly launched back in 1931: Political and Economic Planning (PEP). Technocrats with Fabian roots and Marxist sympathies, PEP wanted nothing less than a centrally planned economy — not just for Britain, but for the empire.

It was, in essence, an intellectual smorgasbord of the finest ethical socialists (Fabians) and scientific socialists (Marxists) of the time — many of whom worked for, or at least fully cooperated with, organisations such as the RIIA and the CFR.

But there’s a major organisation missing from this picture. And it’s one of the most secretive of the lot — a kind of philosophical priesthood that revolved around the intellectual centre of gravity that was Cambridge.

They called themselves the Apostles.

They weren’t a political party, or a formal society. They didn’t publish manifestos or hold public conferences, yet their influence was everywhere. Members included Bertrand Russell, John Maynard Keynes, Leonard Woolf, G.E. Moore, E.M. Forster, and later Anthony Blunt and Guy Burgess. Economists, philosophers, novelists, and — notably — spies.

And this is where we turn to Richard Deacon’s 1985 book, The Cambridge Apostles1, to shed some light on this highly secretive society.

It was the brothers Goncourt who first made the observation that if two men who both spoke the English language were to be cast away on an uninhabited islane, their first consideration would be the formation or a club.

In Britain at the time, clubs were more than social conveniences — they were the architecture of power. And nowhere was this more true than in Cambridge.

… society of the Apostles… the influence of its members has been considerable on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean and in all spheres of life from administration…

This was less of a debating society. Its alumni sat at the highest levels of finance, intelligence, and governance, framing not just policy but the very terms of political legitimacy across the Anglo-American sphere.

With the Cambridge Apostles it was caused by the revelations between 1979 and 1982 that some members of the Society had been agents of the Soviet Union.

The deeper revelation is actually structural, as the same network responsible for building Western institutions also commonly harboured dual loyalties.

… the Apostles was a society with a membership of some few hundreds over a period of 165 years, including… Bertrand Russell, Lytton Stratchey and Roger Fry in an earlier age, and in more recent times Lord Keynes, Lord Rothschild, Lord Annan, Peter Shore and Dr Jonathan Miller. Not to mention scores of others who, though less well known, had made important contributions to politics, the arts, science and medicine

In other words, this was the recruiting pool for global governance before the term existed. The Apostles supplied not just brains, but belief: that the world must be run by those capable of discerning its highest moral direction — ie, themselves.

I have been supplied with lists of members and secretaries of the Society in great detail up to about 1950. Prior to that there have only been a few rather puzzling gaps in the lists (almost as though they have been censored).

Ie, the closer one gets to the formation of the postwar order — Bretton Woods, the UN, the rise of global scientific planning — the hazier the Apostolic record becomes. And likely not because no one was involved, but rather because everyone was.

Undoubtedly the revelations made about Soviet agents among the membership have caused the Society to wish to avoid publicity for some years to come.

A convenient silence — not just for the Apostles themselves, but for the many institutions downstream of their worldview.

Since World War I there have been other close associations between the Apostles and the United States and Canada. This has been particularly true from the end of the 1930s

Which is exactly when global governance began to shift westward. But the ideas — the ethical socialism, the elite tutelage, the conviction that planning must supersede politics — those had already been seeded. By the time Bretton Woods convened, the Apostles’ gospel had crossed the Atlantic.

Henry Sidgwick… became a disciple of John Stuart Mill’s utilitarianism, and thus Mill took the place of Coleridge as the Apostles’ chief inspiration from outside the Society… his major work, Methods of Ethics, published in 1874, won him a considerable reputation outside the university just as much as in it. In 1883 he was elected professor of moral philosophy, a post he held until his death…

In many ways, Sidgwick turned the Apostles from a poetic salon into a moral laboratory — replacing Coleridge’s spiritual idealism with Mill’s secular universalism.

‘Sidgwick himself thought that the Apostles ‘absorbed and dominated’ him, but Leonard Woolf made the point that this was ‘not quite the end of the story…‘

Woolf, who in 1916 penned International Government, understood what Sidgwick perhaps did not: the Apostles didn’t just absorb their members into a members’s list — they embedded them within the future global governance structure.

The society helped shape and sharpen minds, and then placed them where influence would matter most in the future of tomorrow.

‘Among other prominent members of the Society in the sixties and seventies of the last century were… Sir Frederick Pollock, Robin Mayor and the Balfour brothers, Francis and Gerald.‘

This was the incubation phase. Not yet the high technocracy of the twentieth century, but the laying of civilisational pipework: law, science, and early elite administration, who would later populate the governing spine of Britain’s key professional and political classes.

Pollock was called to the Bar in 1871 and then appointed professor of jurisprudence at University College, London, also finding time to produce a life of Spinoza. Mayor… His daughter, Teresa, eventually married another Apostle and became Lady Rothschild.

The marriage of philosophy and finance overlapped at every level: intellectual, bureaucratic, even through family. They were interfacers between legacy aristocracy and emerging professional elites, though the former would probably have objected had they understood where this ultimately took them.

Family links in the society were fairly frequent. Apart from the Trevelyans, the Lytteltons, the Balfours… some assert that Arthur James Balfour, later Earl Balfour and the creator of the Balfour Declaration on Palestine, was a member of the Society… But while A. J. Balfour’s name appears on one list of early members, it is omitted on two others, …

Quite the omission, it has to be said2.

As for Balfour:

‘However, though there now seems to be little prospect of proving it, further research suggests that A. J. Balfour may well have been a member, albeit as briefly as Henry Roby. Educated at Eton and Trinity, of which college he was made an honorary Fellow in 1902, Arthur Balfour was, of course, a leading light in that other small and elite society called the Souls…‘

All Souls at Oxford, incidentally, was the prime recruiting ground of the Round Tables, ie Rhodes3.

Thus, even if his Apostolic credentials remain ambiguous, he still moved in the same ideological culture.

The late Guy Burgess, himself an Apostle in the 1930s and unfortunately now best known for his defection to the Soviet Union with Donald Maclean in 1951, has stated that ‘Arthur Balfour was selected as a member for the Society, but owing to very special circumstances was allowed to withdraw from it.’

An early example of plausible deniability, perhaps, but Balfour's proximity to the Apostles was close enough to matter — yet distant enough to be denied.

‘Dr Whitehead came from a family of clergymen and his chief influence in the Society was as a spotter of talent and a recruiter of new members. He started out in life as a mathematician and then became a philosopher, finding himself more at home in that field than in religion.‘

Like Sidgwick before him, Whitehead helped reframe the club’s function to become a mechanism for intellectual filtration.

‘Meanwhile Sidgwick had not helped the cause in which he believed by establishing contacts with the notorious Madame Blavatsky, who in her time appeared as a remarkably sincere medium to some and an outrageous fraud to others‘

In the late Victorian intellectual world, science, ethics, and metaphysics were still part of the same project: finding an epistemic foundation for human governance. Blavatsky just took it to its theosophical extreme4.

‘Perhaps his occasional waspish remarks did not commend him to his fellow Apostles, as hardly any of them, except Bertrand Russell in a later age, had anything to say about him. Russell, who owed his nomination to the Society to Whitehead, was hardly complimentary about his mentor‘

The Apostle tradition wasn’t immune to generational betrayal. Whitehead mentored Russell, Russell mocked Whitehead. Yet both remained loyal to the core idea.

‘… the French economist, Proudhon, were sometimes cited in debates, but the man who captured the imagination of some Apostles was Prince Peter Kropotkin… Kropotkin was at that time weighing up his chances of finding support for his socialist-anarchist theories in Victorian England.‘

And Kropotkin found it — not among the proletarians, but among Cambridge’s intellectual elite.

Even revolution had its limits when filtered through a Cambridge lens:

‘But even those Apostles who supported Kropotkin soon found that they were themselves not ready to embark on quite so violent and provocative a programme as he suggested, which was ‘to attain ... the annihilation of all rulers, ministers of State, nobility, the clergy, the most prominent capitalists and other exploiters, any means are permissible, and therefore great attention should be given specially to the study of chemistry and the preparation of explosives, as being the most important weapons‘

The Apostles were happy to host radical ideas — just not to act on them. Kropotkin offered total system reset; yet the Apostles preferred soft capture, a view aligned with that of contemporary Fabians.

And there was a considerable overlap between Apostles and Fabian membership. More on that soon.

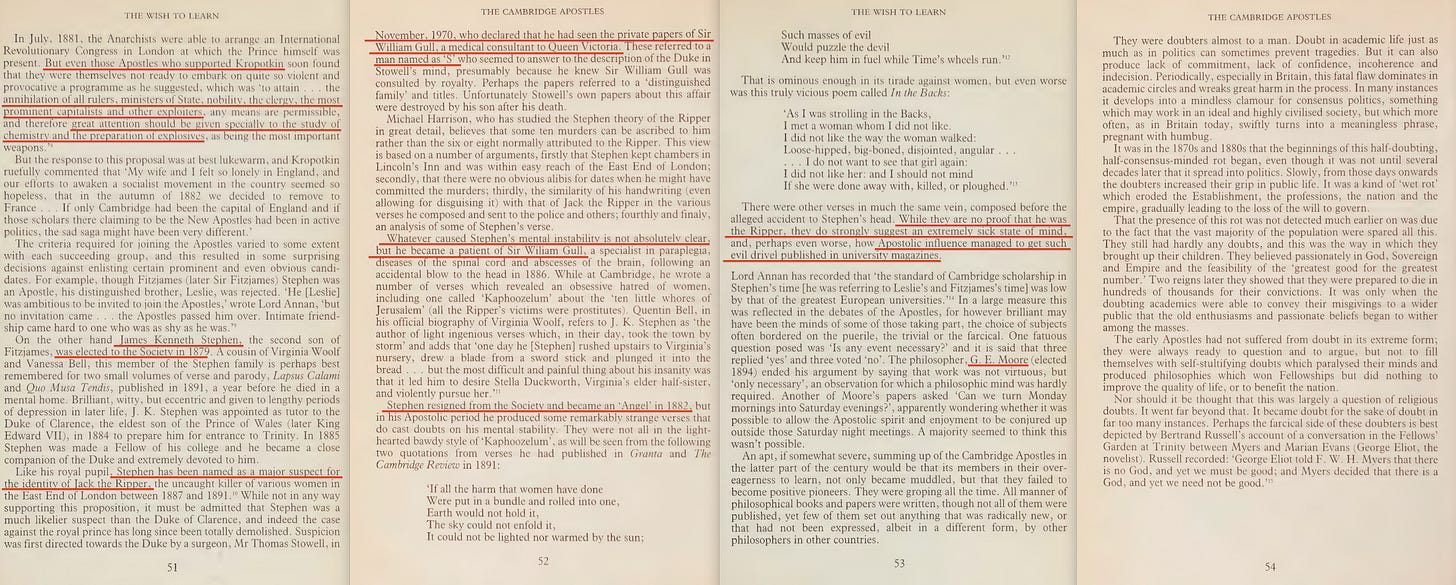

‘James Kenneth Stephen, the second son of Fitzjames, was elected to the Society in 1879… Stephen has been named as a major suspect for the identity of Jack the Ripper…‘

And this should hint at the ideological elasticity of the group.

Yet, this was a time of change:

‘The Edwardian age is generally seen today as one in which all classes managed to enjoy themselves in the belief that the British Empire would last forever.‘

Though the second empire was already beginning to fracture, the elite remained serenely oblivious.

‘As far as the educated classes were concerned, Bertrand Russell expressed this complacency rather differently. He said that he noticed a great change in the Apostles from the generation ten years junior to his son. ‘We are still Victorian,’ he remarked, but, referring to the Keynes and Strachey generation, they ‘aimed rather at a life of retirement…‘

The new ideal was quiet domination — moral superiority expressed through taste, irony, and… governance by cleverness.

Yet even the Apostles themselves failed to grasp the deeper shifts beneath their feet:

‘It was that early Edwardian failing of the Apostles trying to be clever for the sake of being clever and often when there was nothing to be clever about. They thought they were the equal of the German philosophers, yet none of them were in the same class…‘

And this proved a spectacular miscalculation. Because over the long term, it was the ideas of those German philosophers that prevailed.

‘Bertrand Russell has paid his own tribute to the Apostles… It is by way of being secret in order that those who are being considered for election may be unaware of the fact… there were to be no taboos, no limitations, nothing considered shocking, no barriers to absolute freedom of speculation.‘

While the Apostles would eventually promote a public-facing ethic of social justice, they applied a very different principle to their own, exclusive circle: unconstrained speculation among the elect.

‘It would be unjust to John Ellis McTaggart not to make reference to his part in a debate on socialism at the Cambridge Union in November, 1889... How, under a socialist ideal, he asked, could a central government, which muddles even the little it has to do at present, control such vast affairs, including business? ‘And could an emotional democracy attain the hardness of head required in a man of business?’‘

This is the core dilemma of technocratic governance: democracy may inspire belief, but only a trained and trusted elite can be relied upon to govern.

‘… later caused Forster to make that controversial statement that ‘If I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country.‘

The Apostolic code held that loyalty to persons — especially those within the circle — outweighed loyalty to political structures. Only between enlightened friends could governance be justified.

‘Roger Fry, the painter and art critic, was also at King’s, and elected an Apostle in 1887. Fry was… a main link with the Bloomsbury Group… New scientific systems'?‘

By the early 20th century, the line from Apostles to Bloomsbury5 was clear: aesthetic judgment became a moral compass; emotional refinement replaced political legitimacy. Art and culture became the new theology.

But planning — scientific, moral, global — was waiting in the wings. And it would soon recruit culture to do its bidding, aided by a considerable overlap in membership.

And soon, a key architect came to join:

‘After Lytton Strachey probably the dominant influence in the Society for many years was John Maynard Keynes. A product of Eton, where he displayed a great contempt for his examiners even though they regarded him highly, he brought to Cambridge a high degree of arrogance and assertion of personal superiority over his contemporaries.‘

Keynes didn’t just join the Apostles — he bent them into a staging ground for elite managerialism.

‘Keynes became secretary of the Society only two years after his election in 1903, when there was only one undergraduate member…‘

With the club in decline, Keynes revived it — by centralising its authority.

‘Professor Arthur Pigou, of King’s, an economist who in many ways rivalled Keynes, never became an Apostle, partly because Keynes wished to keep the Apostolic fishpond free from other economists as far as possible. Scientists were also disfavoured… Leonard Woolf controlled the literary pages of The Nation, Desmond MacCarthy did much the same with the New Statesman while Strachey’s uncle was at the helm of The Spectator.‘

Economists not aligned with Keynes were excluded, and scientists were broadly unwelcome. Literary and editorial influence, meanwhile, was consolidated to serve a single ideological trajectory.

‘Though Keynes was anti-Fabian, Fabianism became a vital topic in Apostolic circles. A Fabian Society had been formed at the University: Hugh Dalton (later to become Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Attlee government of 1945-50) was one of its earliest presidents, and in 1909 he was succeeded by Rupert Brooke‘

Despite Keynes’s disdain for Fabian gradualism, the overlap in ambition was unmistakable: rule the world through technocratic vision — cloaked in the language of democracy and social justice.

‘Both Brooke and Gerald Shove were briefly secretaries of the Society, and it was about this time that the two foreigners of some distinction were elected - Ludwig Wittgenstein and Ferenc Istvan Denes Gyula Bekassy. They were elected in the same year, 1912…‘

And by 1912, the Society was no longer merely British. It was becoming a moral vanguard for transnational governance.

Yet the future cosmopolitan order didn’t arrive without its battle:

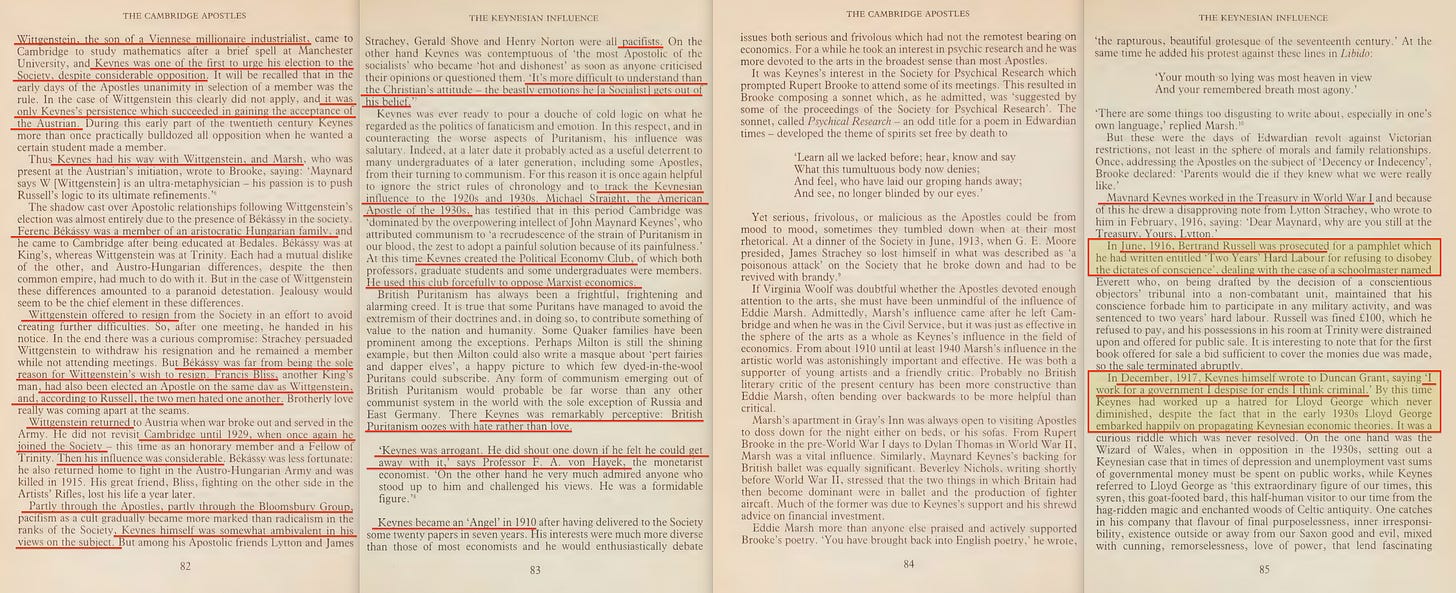

Wittgenstein, the son of a Viennese millionaire industrialist, came to Cambridge to study mathematics after a brief spell at Manchester University, and Keynes was one of the first to urge his election to the Society, despite considerable opposition

Wittgenstein was brilliant, foreign, and temperamentally volatile — everything the Apostles both feared and quietly admired. But his time among them was not marked by pure success.

But Bekassy was far from being the sole reason for Wittgenstein’s wish to resign. Francis Bliss, another King’s man, had also been elected an Apostle on the same day as Wittgenstein, and, according to Russell, the two men hated one another.

Personal animosities often masked deeper ideological rifts. In this case, the frictions between nation, class, and temperament nearly undid the cosmopolitan project.

Wittgenstein returned to Austria when war broke out and served in the Army. He did not revisit Cambridge until 1929, when once again he joined the Society - this time as an honorary member and a Fellow of Trinity. Then his influence was considerable

By the time Wittgenstein returned, the world had changed — and so had Cambridge.

‘… track the Keynesian influence to the 1920s and 1930s. Michael Straight, the American Apostle of the 1930s, has testified that in this period Cambridge was ‘dominated by the overpowering intellect of John Maynard Keynes’, who attributed communism to ‘a recrudescence of the strain of Puritanism in our blood, the zest to adopt a painful solution because of its painfulness.’ At this time Keynes created the Political Economy Club, of which both professors, graduate students and some undergraduates were members. He used this club forcefully to oppose Marxist economics.‘

This would appear, at first glance, to contradict Keynes’s later legacy. But what he wrote in 1936 would enable an almost identical outcome.

The ultimate destination was identical, but it was ethical socialism which won the day, amd not revolutionary Marxism, as the latter was considered ill-suited for the empire at the time, and especially Britain itself. A realisation with which the Fabians happened to agree.

Maynard Keynes worked in the Treasury in World War I and because of this he drew a disapproving note from Lytton Strachey… In June, 1916, Bertrand Russell was prosecuted for a pamphlet which he had written…

The entire Apostolic milieu, though elite, was thick with tangents and sympathies that diverged sharply from the official ethos of the British Empire.

‘In December, 1917, Keynes himself wrote to Duncan Grant, saying ‘I work for a government I despise for ends I think criminal.’ By this time Keynes had worked up a hatred for Lloyd George which never diminished, despite the fact that in the early 1930s Lloyd George embarked happily on propagating Keynesian economic theories…‘

And yet Keynes kept working — because he had a different objective. His allegiance was not to the government, but to the system which after all had to be steered… in a different direction, eventually.

And a different direction indeed was required to pull this off:

‘The truth is that the kind of Keynesian plan which Lloyd George had proposed could only have been achieved by drastic controls and a socialist economy.‘

And that is precisely what came later — not through popular will, but through institutional capture.

‘The Keynesian programme on which Lloyd George went to the polls in 1929 was a technocrat’s blueprint without the positive co-ordination of state and private enterprise measures for putting it into action…‘

The vision was in place, but the coordination between government, industry, and finance was still under construction. But not for long.

‘Keynes himself was not always consistent in this era. He opposed Britain returning to the Gold Standard, yet argued against devaluation; while sometimes urging an agreed policy of reducing some incomes, he dismissed any suggestion in cuts in wages; finally, Keynes, the Free Trader, for a brief period argued in favour of some tariffs.‘

And this is revealing. Keynes was not ideologically rigid, but tactically adaptive. Whatever position best served the structure he aimed to build — that was the one he took.

‘Apostolic influence in World War I was minimal… the pacifist members of the society - Lytton and James Strachey, Dickinson, Hardy, Norton, Sanger, Sydney-Turner, Bertrand Russell, Woolf and Keynes - were against the war in varying degrees‘

Most Apostles opposed the war not out of anti-imperial conviction, but because they believed empire should be governed differently… from behind the curtain.

Yet:

The others who joined the Society in this period were Julian Bell, son of Clive Bell (who had never been an Apostle); Francis Crusoe, Anthony Blunt and Henry John Bevin Lintott.

Blunt, of course, would later be unmasked as a Soviet agent.

Outside the Society there was widespread evidence of a leftward-cult which extended from serious support for socialism on the one hand to a commitment to a ritualistic Marxism at the other extreme.

And it wasn’t merely ideological. It was aesthetic, moral, and institutional — a mood among the intellectual elite that veered from reformist planning to veiled devotion to Soviet power, observed through especially the Science and World Order conference in London in 1941.

The fact that a number of its members allowed themselves to become either deliberately conscious agents of the USSR, or to find themselves duped into serving the Soviet Union, was due in no small measure to the anti-Establishment traditions of the Apostles. It all began in the last century with the Society's desire to undermine the dominating position of the Church of England in university life.

Over time, the Church of England was replaced with the Church of Scientific Socialism, and praise of a model which saw widespread calamity in the East.

It was among the scientist dons that pro-soviet pronaganda was most marked in this period. Those who lent close support to the National Association of Scientific Workers included Blackett, Crowther and Needham. Long before the 'thirties this had produced results beneficial to the Soviet cause. The physicist Crowther, chief of all fellow-travelling British scientists, had made seven trips to Russia in as many years, and, as a result, became one of the leading exponents of the USSR as being the embodiment of scientific progress.

The Soviet model appealed especially to those who believed in planned economies and technocratic control. Of course, those also commonly believed they were the ones who should plan on the behalf of others.

Needham was that very dangerous combination - a scientist and a Christian Marxist… There was one essay of his, published in 1932, in which he discussed nude bathing and religion… addressing the Modern Churchmen's Union in 1937… ‘we owe it largely to the genius of no other than Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin

The counterargument here is that Needham was unaware of the atrocities committed under Stalin, which accelerated especially after 1936.

But this claim simply does not hold up to water, as Julian Huxley and others certainly were aware of the conditions in the Soviet Union at the time.

It would be totally wrong to suggest that the Apostles had gradually turned subversive, or pro-communist.

This comment appear particularly unfortunate, given what comes next:

In Society meetings in this period papers read were 'discussed rather than debated,' according to Michael Straight.

Because Michael Straight wasn’t just any Apostle. He was an actual Soviet spy6.

So at this stage, it should be fairly clear — the Cambridge Apostles gradually centralised its authority, and Leonard S. Woolf, Lord (Victor) Rothschild, and Keynes were key members when this took place. The society gradually came to be riddled with future spies and what appears to have been a gravitational influence exerted by scientific socialism.

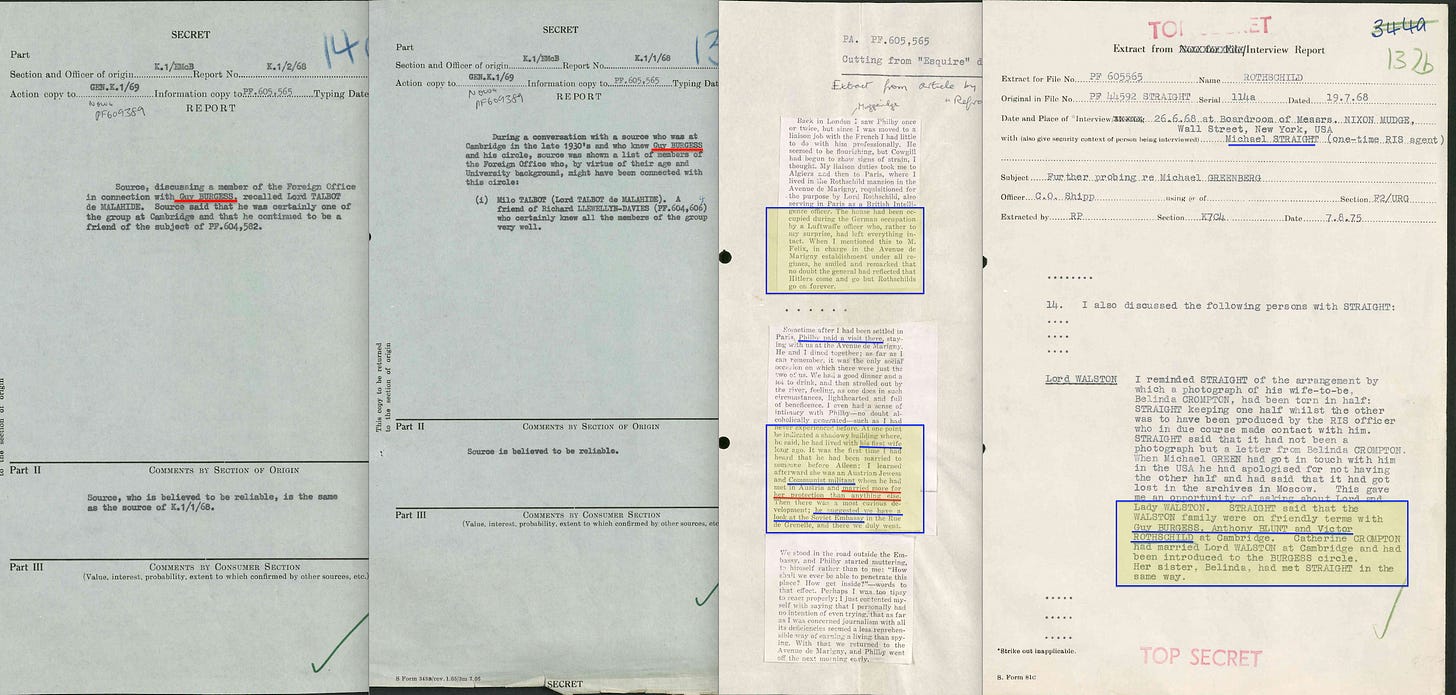

But how riddled, and how influenced? Well, that’s where MI5 archive itself adds further, clarifying detail, not least through a 148 page report on Victor and Teresa Rothschild7:

According to MI5 reports, Lord Talbot de Malahide was identified by a reliable source as ‘certainly one of the group at Cambridge’ — referring to individuals of aristocratic and academic background, some of whom ‘might have been communists’. Talbot remained closely connected to other key figures, including Richard Brooman-White, and reportedly knew all members of this group ‘very well’. This aligns with further testimony describing how, years later, figures like Victor Rothschild found themselves surrounded in Paris by members of the same circle — among them Michael Straight, Anthony Blunt, and Guy Burgess.

As for the matter of Marxist infiltration during the war — Rothschild himself offered a telling remark:

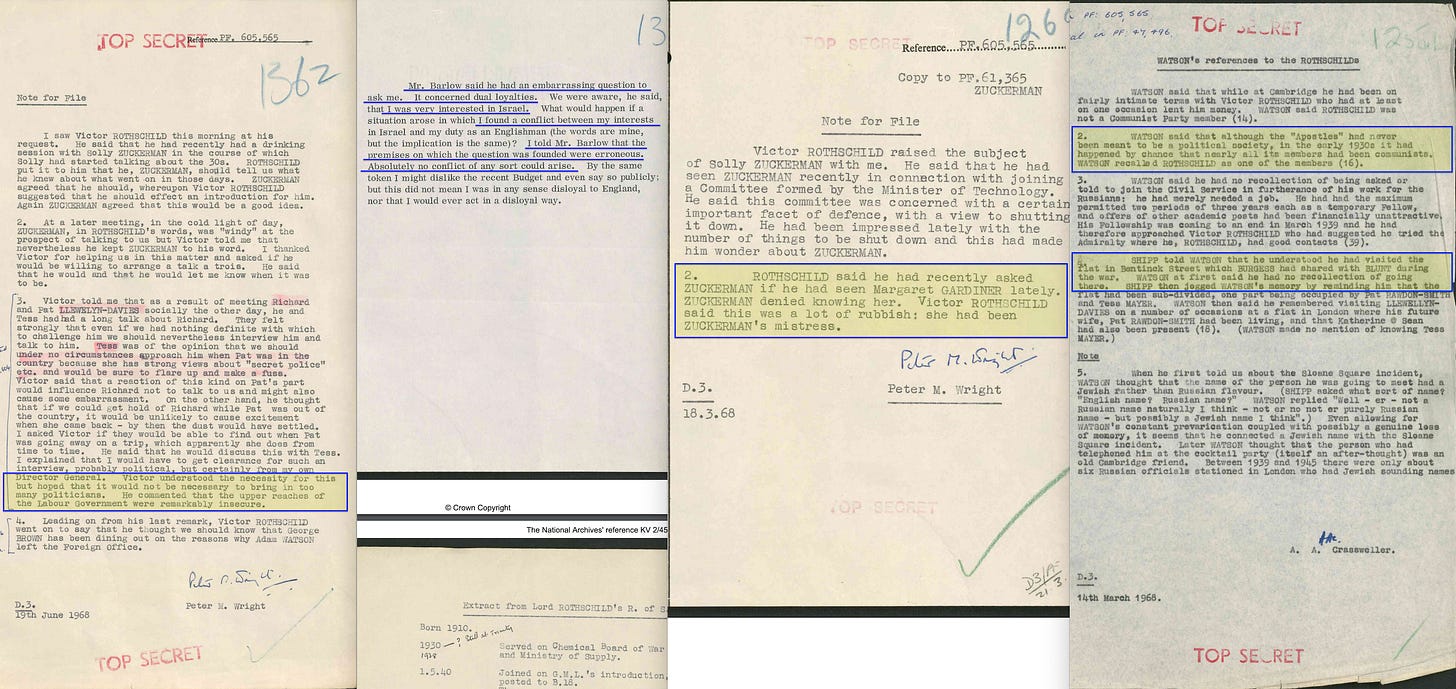

Victor understood the necessity for this but hoped that it would not be necessary to bring in too many politicians. He commented that the upper reaches of the Labour Government were remarkably insecure…

Which is precisely why permanent control required something beyond electoral politics. Stability had to be engineered.

‘Mr. Barlow said he had an embarrassing question to ask me. It concerned dual loyalties. We were aware, he said, that I was very interested in Israel. What would happen if a situation arose in which 1 found a conflict between my interests in Israel and my duty as an Englishman (the words are mine, but the implication is the same)? I told Mr. Barlow that the premises on which the question was founded were erroneous. Absolutely no contlict or any sort could arise.‘

A flat denial — yet the core issue of dual-purpose service was not denied, merely reframed. But as for the key question — how riddled, and how influenced:

‘WATSON said that although the ‘Apostles’ had never been meant as a political society, in the early 1930s it had happened by chance that nearly all its members had been communists. WATSON recalled ROTHSCHILD as one of its members‘

The official line is that this was simply a reflection of Cambridge’s prevailing ideology at the time, eventually spilling into Science and World Order in 1941. In reality, it was less a coincidence and more an indirect confirmation: the Apostles had ceased to be a debating society and had become an incubator of communism.

As for Victor Rothschild himself — he suddenly found himself on the receiving end of undesired attention later in the 1970s.

An episode of the BBC’s 24 Hours aired allegations that linked him to espionage, prompting MI5 to review his background. The context? A growing unease within the security services that Rothschild had long been surrounded by individuals now known to have spied for the USSR — including Anthony Blunt, Guy Burgess, and Kim Philby. What had once been a private matter among an elite network was now seeping into public discourse.

Rothschild, for his part, continued to deny any wrongdoing — and was never formally charged.

But what actually took place at the time?

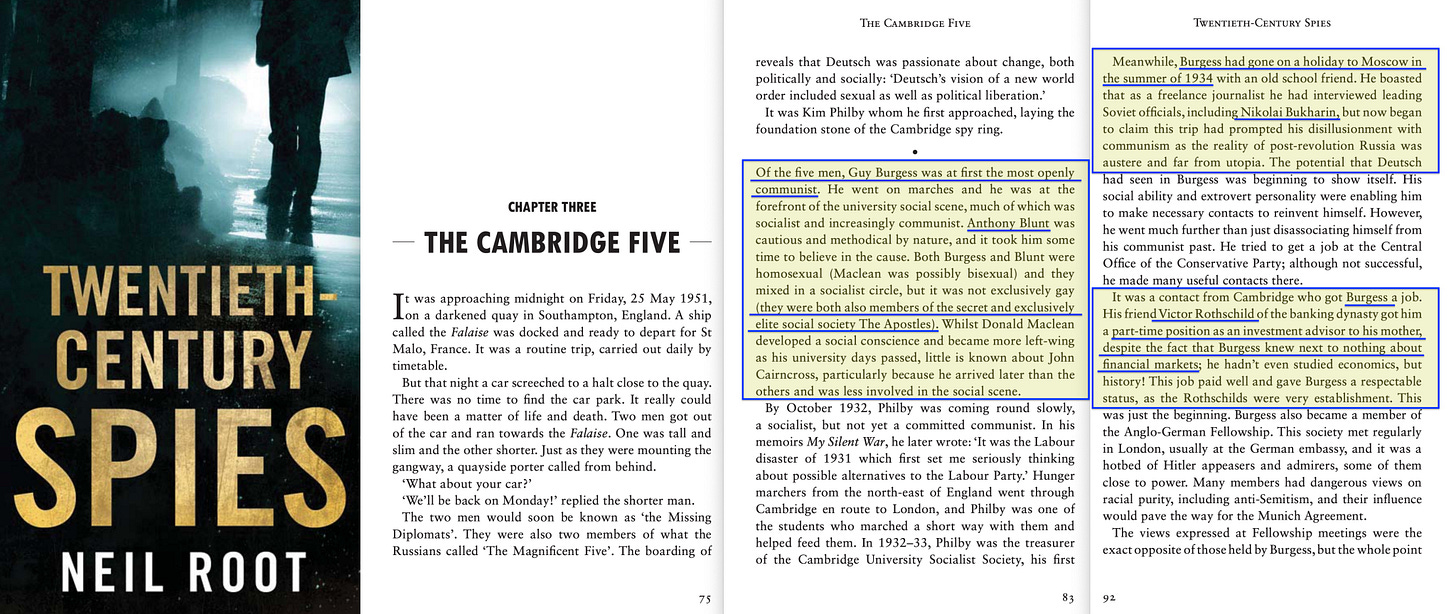

Neil Root’s Twentieth-Century Spies8 incidentally includes a chapter on the Cambridge Five. And setting aside contemporary thoughts on ‘alternate lifestyles’, back in the 1930s it was far from broadly accepted. Yet, both Burgess and Blunt were openly gay, with Maclean possibly bisexual — all of them deeply embedded in socialist circles, and crucially, all of them were members of the Cambridge Apostles.

By 1934, under Stalin’s tightening regime, Burgess took a ‘holiday’ to the Soviet Union. There, he interviewed Nikolai Bukharin — the very same Bukharin who had helped introduce Bogdanov’s Tektology to the West, and who served as a pivotal intellectual bridge between Eduard Bernstein’s revisionist Marxism and Lenin’s New Economic Policy. Burgess’s trip was far more than ideological tourism; it marked an intensifying identification with the Soviet experiment.

And the most remarkable part of the chapter? Despite having no qualifications in finance — never having studied economics or worked in the field — Burgess was given a well-paid position as an ‘investment adviser’ to none other than Victor Rothschild’s mother. The potential implications should be obvious, though this too will, of course, be dismissed as mere coincidence.

We have frequently discussed Golitsyn. His Perestroika Deception outlined a long-term strategy initiated under Khrushchev — one aimed at a managed convergence between the Soviet bloc and the capitalist West through a reconfigured, NEP-style framework. That strategy, Golitsyn argued, would culminate decades later with Gorbachev’s Perestroika — a simulated liberalisation designed to secure global synthesis, not collapse. Whether or not one accepts his thesis in full, the credibility of parts of his account becomes more difficult to dismiss when viewed in light of concurrent developments, especially the rise of global governance during the same period.

I personally find it credible — especially when considered not only in the context of the environmentalism that took hold during this period (a campaign that could hardly have been anything but outright fraudulent — see: The Missing Link) but also in light of Gorbachev’s own speeches in the late 1980s.

According to Peter Wright’s Spy Catcher9, in 1968 Soviet defector Anatoliy Golitsyn was granted access to MI5’s most sensitive personnel files in an effort to identify spies potentially exposed by the VENONA decrypts. After months of meticulous review, Golitsyn made a stark declaration: ‘Your spies are here’, he said, pointing to two specific files. ‘They belonged to Victor and Tess Rothschild’. While Wright and others in the Service objected — noting that Victor was considered one of MI5’s most trusted allies — Golitsyn remained firm. His methodology, he claimed, had uncovered deep and previously undetected infiltration.

And per JD Bernal’s book, The Sage of Science10, Victor Rothschild lived in a basement flat just off Oxford Street:

‘Sage himself, on at least one night during the Blitz, took shelter in the basement of a flat owned by Lord Rothschild at 5 Bentnick Street, just off Oxford Street. Two of Rothschild’s tenants were the Cambridge communists, Anthony Blunt and Guy Burgess, who gave the premises ‘the air of a rather high-class disorderly house, in which one could not distinguish between the staff, the management and the clients. Burgess was working at the War office and Blunt in MI5, alongside Rothschild who had recruited him.’

In the middle of wartime London, the Cambridge network — including Blunt and Burgess — was operating openly from a shared residence, embedded inside the War Office, MI5, and foreign intelligence, with Victor Rothschild’s home as the node that tied it together.

’Malcolm Muggeridge, also working as a wartime intelligence officer, was taken to the flat once and found ‘John Strachey, J.D. Bernal, Anthony Blunt and Guy Burgess, a whole revolutionary Who’s Who’. Muggeridge, ever the sharp-eyed moralist, felt a visceral repulsion for this millionaire’s nest, …‘

Even Muggeridge — no stranger to espionage — was disturbed by the sheer concentration of Marxist influence, and Rothschild’s proximity to it.

‘The irresistible question arises as to whether there was any intrigue going on between Sage and Blunt and Burgess, who were later exposed as spies and were passing information to the Soviets during the war.’

Naturally, this will be dismissed as circumstantial. But the number of “coincidences” here borders on statistical impossibility. The flat appears to have functioned as a semi-clandestine salon of ideological convergence — a logistical and intellectual hub for the wartime left.

’Sage had known Rothschild since the latter became a Fellow of Trinity in 1935. Rothschild was a member of the Apostles, and he, Burgess and Blunt would all have been aware of Sage as one of Cambridge’s leading communists. The flat was therefore a natural meeting place for like-minded Cambridge men, and there were even two left-wing Cambridge women living there, who might have been responsible for Sage’s presence‘

This was no ordinary wartime bunkhouse. It was an intentional gathering point structured around shared ideology — under the watch and apparent approval of Victor Rothschild.

‘Recent publication of the Venona decrypts has exposed both J.B.S. Haldane and Ivor Montagu as secret agents, who actively passed information to the Soviets early in the war, but there has been no suggestion that Sage was involved. He had detailed knowledge of civil defence and bomb disposal,‘

Even Haldane — long regarded as an intellectual titan — was ultimately confirmed to have been a Soviet agent. That this detail appears in a book about Bernal — himself a committed Marxist and Soviet sympathiser — only strengthens the argument.

‘Goronwy Rees, a journalist friend of Burgess who had joined the Army in 1939, recalled that visitors to Bentinck Street ‘all appeared to be employed in jobs of varying importance, some of the highest, at various ministries; some were communists or ex-communists‘

In sum, 5 Bentinck Street was no ordinary address. It was a wartime convergence point of ideology, espionage, and administrative access — a salon for a new elite whose shared conviction appears to not have been patriotism, but a belief in the inevitable global ascendancy of scientific socialism.

Roland Perry goes a step further in his book, The Fifth Man11. Acorrding to this controversial book, Rothschild was not simply a financier dabbling in science, but a man who — according to multiple ex-KGB sources — operated at the core of one of the most consequential espionage networks of the 20th century. During World War II, while officially acting as MI5’s scientific adviser, he was reportedly also supplying the KGB with comprehensive intelligence on radar, sonar, uranium enrichment, and bomb detonation technologies. More than a passive conduit, he had access to virtually every major military research site in Britain — including Porton Down — and was allegedly able to remove classified material from labs and forward it to the Soviets without being caught. His supposed espionage even extended to sabotaging internal investigations: no scientist ever reported suspicions, and he never failed a security inspection.

What makes this even more striking is Rothschild’s proximity to the core Soviet agents themselves. His three-story London flat doubled as a salon for fellow Apostles-turned-operatives: Anthony Blunt, Guy Burgess, Kim Philby, and their couriers. Tess Mayor, later Lady Rothschild, was also entangled in these circles, and her cousin-in-law Malcolm Muggeridge came to openly question Rothschild’s allegiances after a chilling dinner in 1944 where Rothschild openly dismissed Allied intelligence superiority. Rothschild’s reach wasn’t limited to Britain — he made intelligence trips to Moscow, cultivated connections in the US nuclear establishment, and was instrumental in transferring the Enigma-derived Bletchley Park intercepts directly to Stalin. Even after the war, he maintained these networks under commercial and scientific pretenses, reportedly embedding himself in Nafta, Shell, and the Atomic Energy Commission while continuing covert relations with KGB liaisons across Europe.

Most explosively, Perry alleges the network delved into more than technical espionage: blackmail, psychological manipulation, and sexual leverage were part of the operational toolkit. Rothschild’s flat was described as a decadent haven — where ‘at times two or more would combine’ — a setting where ideological and strategic bonds overlapped, reinforcing group cohesion and loyalty. His supposed spymastering was not motivated by money, but by Marxist conviction: a belief that Communism would — and should — triumph over capitalist democracies.

According to Perry, Rothschild’s ultimate aim was not sabotage for its own sake — but to help shape the postwar world order itself by ensuring a scientific elite, liberated from national loyalty, would take control of history.

And when Yuri Modin published his 1994 French-language account of the Cambridge Five, Mes Camarades de Cambridge, he was reportedly astonished to discover that key detail had been altered in the English translation12.

As for Leonard S. Woolf — whose 1916 report International Government became the blueprint for the League of Nations — he too was reportedly a friend of Victor Rothschild13.

Keynes, of course, went on to become a key architect of the new global financial order — the very system Alfred Zimmern leveraged to advance his vision of a Third British Empire, one inspired by international social justice and British in name only.

Keynes — whose General Theory largely codified what central banks had already implemented through RIIA-backed research — had earlier been involved in the founding of the BIS and played a central role at the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference, which established the tripartite global financial order now being consolidated through the BIS offshoot, the Financial Stability Board.

A global financial order now aims to consolidate fiscal and monetary macroeconomic policy—entirely outside democratic representation. It’s framed more palatably, of course, but any future politician who dares to object will be Truss’ed without delay. And with that initiative firmly in motion, the next step becomes rather obvious:

Positive money. A system in which the creation and direction of credit is no longer mediated by private banks or parliaments, but entirely at the discretion of unelected central banking planners — guided by claims of ‘price stability’, ‘resilience’, and elements of Zimmern’s international social justice posing as the ‘common good’.

And this initiative does appear to be in an early stage of development, with a 2021 discussion paper detailing14:

Implications for monetary and financial stability arise because commercial banks, and the money they create through lending, are an important part of the economy. By offering people an alternative to commercial bank money, new forms of digital money could affect the cost and availability of borrowing from banks. All else equal, that could make it more difficult for monetary policy to ease financial conditions. Against that, new forms of digital money could increase the resilience of payments.

An ‘alternative to commercial bank money’ need not be created through private lending at all — it could be a currency with 100% central bank backing, exactly as proposed by the Positive Money framework. A fully public trading currency, insulated from private leverage.

At that stage, the system advances toward coupling these dual CBDCs to a designated store of value — initially, this could take the form of carbon emission permits. These initiatives, incidentally, are also already well underway.

Should you seek further information on the main storyline, then Roland Perry also wrote a book on Michael Straight15, while Miranda Carter16 and Barrie Penrose17 focused on Anthony Blunt. Nigel West later covered Soviet infiltration within MI518.

But I have only one final comment:

Ultimately, none of the Cambridge Five were ever prosecuted. And though it will be claimed that the statute of limitations had expired, it begs one question in particular: who, exactly, did that benefit?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The price of freedom is eternal vigilance. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.