Agents for the Rothschilds

In 2016, the publisher De Gruyter released an essay by Rainer Liedtke titled Agents for the Rothschilds: A Nineteenth-Century Information Network1.

Drawing on the Rothschild Archive London — correspondence from over one hundred business agents working for the various Rothschild houses — Liedtke documented a recruitment and intelligence operation that spanned the European continent and reached into Latin America for most of the nineteenth century.

The paper describes a system in which agents were placed in locations where the Rothschild banks did not maintain a permanent presence. These agents carried out business transactions, gathered political and economic intelligence, and forwarded information that enabled the family to make decisions ahead of competitors and, frequently, ahead of even governments.

Liedtke notes that what we now would consider insider trading ‘was commonplace in nineteenth-century finance and part of the salary package of employees of financial institutions’. The agents were not merely tolerated in this practice — they were compensated through it.

The recruitment criteria tell their own story. Trust was paramount, and two principal routes existed for earning it: being a relation of the family, or having worked within one of the houses for a considerable period. Marriage was the preferred option, and these marriages ensured that important business locations were ‘covered in the long run by trustworthy representatives’.

Liedtke is explicit about one boundary:

… such men never gained access to the decision-making circle of the family but instead maintained their own business interests separately, albeit profiting significantly from contacts to the Rothschild network.

The agents were operationally essential, but they remained permanently outside the core. Only born Rothschilds were fully trusted. The ‘quintessential criterion’ for whether a Rothschild bank existed in a given city was whether a Rothschild was willing to move there.

He also documents a deliberate policy of heterogeneity. Despite being Jewish, the Rothschilds employed non-Jewish agents as a matter of strategy. A homogeneous network, Liedtke explains, would be ‘self-referential’ — limited to the social circles its members already moved in.

Diversity of background expanded the network’s reach into drawing rooms, ministries and trading floors that a uniformly Jewish network could not access. Agents sent to locations where they had no prior ties were valuable precisely because they lacked local loyalties — their ‘foreignness’ meant their primary allegiance remained with the principals abroad, uncompromised by existing relationships in the places where they operated.

Liedtke records a shift over time in what the principals expected. In the early decades, the network’s value lay in raw market data — commodity prices, exchange rates, shipping movements. After the telegraph commoditised this kind of information in the mid-nineteenth century, the agents’ importance shifted towards strategic political assessment: who was likely to form a government, which minister could be cultivated, what policy was being contemplated before it was announced.

Only one vulnerability recurs in the archive. August Schönberg, dispatched to New York and later known as August Belmont, declared himself the Rothschild agent on Wall Street without authorisation. The distance between New York and London made control impossible. Belmont could not be dislodged, and the family was forced to tolerate an agent who had, in effect, gone rogue.

Liedtke treats Belmont as the system’s one significant failure.

Fritz Stern’s Gold and Iron2 (1977) provides the most detailed case study of the template in action. Gerson von Bleichröder — whose family bank functioned as a ‘branch office in Berlin of the Rothschild banking house’ — became Bismarck’s personal financial agent, managed his portfolio, bribed officials on his behalf, financed wars while bypassing parliamentary opposition, and served as intermediary between European finance and the Prussian state. Bleichröder’s ‘remarkable and long-running relationship with the Rothschilds made his services doubly worthwhile to both Bismarck and Germany’.

Yet Bleichröder was never admitted to the inner circle of power. After Bismarck’s death, he ‘dropped out of German historiography like a stone in water’ — the agent vanished while the principal endured.

The consequences of Bleichröder’s agency extended well beyond Bismarck’s portfolio. Following the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, Bismarck sent Bleichröder to Versailles as his financial adviser to negotiate the terms of the French indemnity. Bleichröder advised on the amount — he had recommended four billion francs; the final figure was five billion, roughly a quarter of French GDP — and subsequently handled the technical processing of reparation payments on the German side. For these services he received the Iron Cross, a military decoration awarded to a banker.

On the French side, it was Alphonse de Rothschild, head of the Paris house, who led the syndicate that raised the bonds to pay the indemnity3. Bleichröder’s own firm then organised a German syndicate to purchase those French bonds. The Rothschild network profited from both ends of a five-billion-franc transaction that reshaped the European balance of power.

The humiliation of the 1871 terms drove France’s demands at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, which opened on the 18th of January — the anniversary of Wilhelm I’s proclamation at Versailles in 1871. Clemenceau sought explicit revenge. The resulting reparations of 132 billion gold marks wrecked the German economy, and it was those reparations that created the institutional justification for the Bank for International Settlements, established in 1930 to administer the payment schedule.

The BIS, however, was modelled on more than the reparations problem. At the Brussels International Monetary Conference of 1892, Julius Wolf, a professor at the University of Breslau, had submitted a project for internationally issued, gold-backed clearing certificates administered by a joint institution in a neutral country — in effect, a globalisation of the clearing house architecture.

At the same conference, Alfred de Rothschild, a former Director of the Bank of England, presented his own paper advocating the London Bankers’ Clearing House as a system approaching ‘perfection’ and arguing against a physical coinage solution in favour of paper certificates representing quantities of metal.

Wolf’s proposal extended onto the international plane exactly the architecture Alfred de Rothschild was championing domestically. The Rothschild agent who shaped the 1871 terms thus set in motion a chain of consequences — the humiliation, the revenge, the reparations, the institution — that landed on a design presented alongside Alfred de Rothschild’s own advocacy at the same table.

The function the BIS was designed to perform — clearing sovereign obligations between states, intermediating capital flows across borders — had previously been performed by multinational merchant banks, the Rothschilds foremost among them. Bleichröder processing reparation payments on the German side while Alphonse de Rothschild raised the bonds on the French side was the BIS function carried out by private agents.

When the institution was constituted in 1930, its founding governance reflected this lineage. The entire American share subscription went not to the Federal Reserve but to a consortium of private banks led by JP Morgan. Parts of the Belgian and French issues also went to private shareholders. In the 1930s, nearly a third of all issued capital was privately held. The corporate form was explicitly chosen, in the words of the Oxford handbook entry, to ‘insulate the Bank from governmental interference’.

An internal Federal Reserve Bank of New York memo from 1929 warned that the bankers’ plan ‘suggests too great of power conferred on private stockholders’ and that private ownership ‘introduces the pressure of profits as opposed to the motive of public service’. The US government did not ratify Federal Reserve board membership until 1994; private shareholders were not bought out until 2001–2005, and only after an arbitration fight.

For over seventy years, the central bank of central banks had private banking interests sitting in its equity.

The clearing house template also migrated into international politics.

In 1916, Leonard Woolf — commissioned by the Fabian Society and a close friend of Keynes — published International Government, which applied the same layered mediation to relations between states: voluntary associations intermediating between governments, permanent secretariats above them, subsidiarity distributing responsibility downward while authority flowed upward.

International organisations would progressively siphon sovereignty off individual states.

The League of Nations was built on this blueprint, and the United Nations inherited it. The same architecture was deployed across both finance and politics within a single generation — and frequently by the same people.

The period during which Liedtke’s archival coverage begins to thin — the late nineteenth and early twentieth century — coincides precisely with this institutional migration. The private functions the agent network had performed for a century were being absorbed into formal organisations: the BIS for sovereign clearing, the League and later the UN for political mediation, the CFR and Chatham House for transatlantic policy coordination. Cecil Rhodes’s vision for the latter — a network of elite influence bridging the Anglo-American world — ran through Rothschild financing from its inception.

The agent network did not disappear, but its function changed. Where the nineteenth-century agents had managed the family’s direct business, the twentieth-century successors would manage the institutional architecture that replaced it — operating not within the Rothschild banks but within the sovereign and multilateral bodies that now performed the Rothschild banks’ historical role at a vastly larger scale.

The family’s reach extended into state intelligence as well.

Victor Rothschild served in MI5 during the Second World War, and his London flat functioned as a gathering point for fellow members of the Cambridge Apostles — a secretive Cambridge society whose membership in the early 1930s, according to MI5’s own files, was ‘nearly all’ communist. Several of those who frequented the flat, including Anthony Blunt and Guy Burgess, were later exposed as Soviet agents.

Woolf and Keynes were also Apostles — as documented in declassified MI5 records and published accounts by former intelligence officers.

Victor later served as research director of Shell, where in 1966 he commissioned James Lovelock to write an essay titled 'Some thoughts on the year 2000'. Lovelock has acknowledged that this work was instrumental in setting him on the intellectual journey that produced his Gaia hypothesis — the view of Earth as a self-regulating organism that would, decades later, provide the conceptual foundation for planetary-scale environmental governance.

Niall Ferguson’s two-volume The House of Rothschild4 (1998–1999), written with unprecedented access to the family archives, documents the broader pattern: a transnational business partnership ‘preserved over five generations through family loyalty, written agreements, and intrafamily marriage’. Between 1824 and 1877, fifteen of twenty-one Rothschild marriages were between direct descendants.

Adam Kuper — who analysed Ferguson’s archive material in a 2001 paper for Social Anthropology5 — arrived at a similar figure: more than 70 percent of marriages in this period were with a father’s brother’s daughter or father’s brother’s son’s daughter, arranged specifically to sustain the partnership between branches. Kuper concluded that the Rothschilds were likely ‘the only banking family who had such an explicit strategy of endogamy’. He also found that the pattern ceased abruptly when the rise of joint-stock companies changed the banking environment — the family could no longer staff every node with born Rothschilds, and the role of marriage recruits and external agents became correspondingly more important.

Thus, across four independent academic studies the method is clear: agents placed where the family requires presence but does not wish to reside, recruited through marriage or long service, compensated through access rather than salary, deliberately heterogeneous, publicly visible and socially prestigious by association, but permanently excluded from the family’s decision-making core.

What these sources collectively describe is a private intelligence operation — one that enabled the family to act ahead of competitors and governments for the better part of a century.

The question is whether this method continued into the late twentieth century.

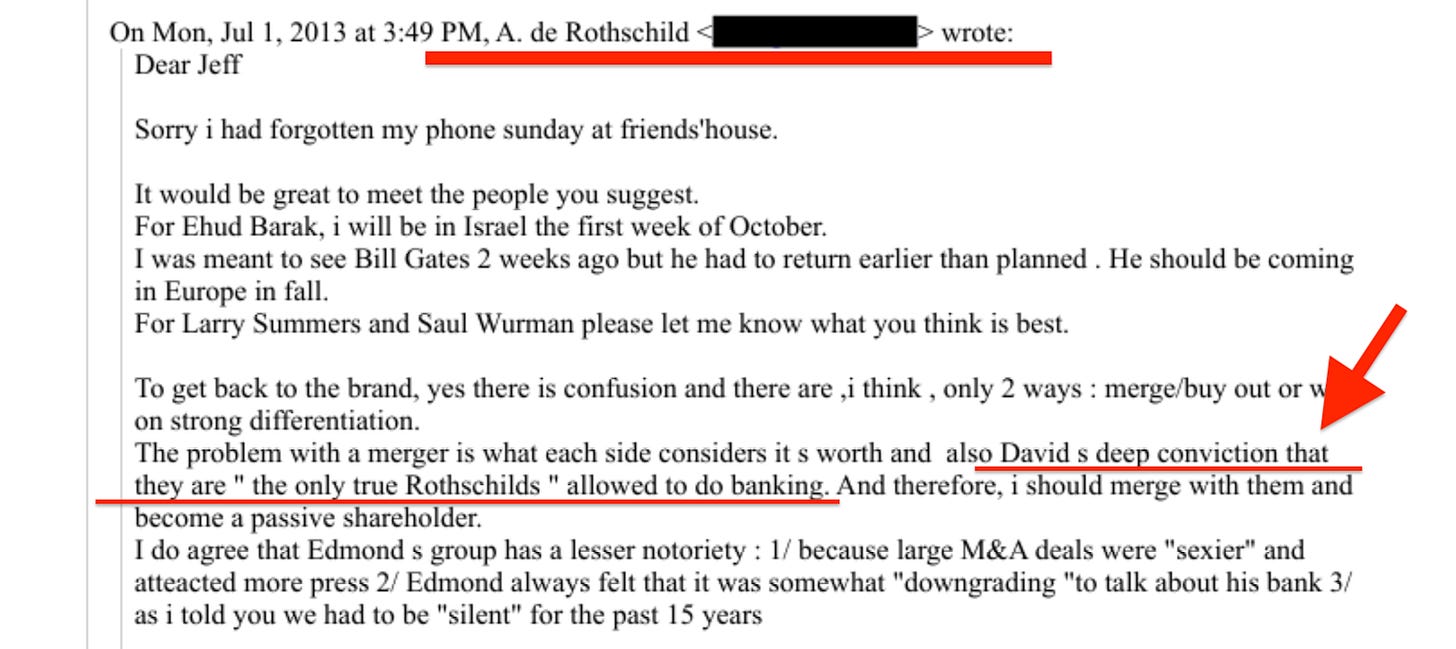

The Epstein Correspondence

The three Epstein essays published on this Substack over the past week traced a network of connections radiating outward from Jeffrey Epstein to figures associated with the Rothschild family. The correspondence released following the US Virgin Islands litigation and the January 2026 DOJ release — over six million pages in total — provides a considerable documentary record.

The most extensively documented relationship is with Ariane de Rothschild, who appears in approximately 5,500 documents in the archive, a volume exceeded by only a handful of figures. Born Ariane Langner in San Salvador, she married Benjamin de Rothschild of the Edmond branch in 1999 — and later became the first person without Rothschild lineage to head a Rothschild-branded financial institution. In Liedtke’s terminology she is a marriage recruit, though the correspondence shows her operating as considerably more.

As documented in the third essay of this series, the correspondence establishes a three-tier reporting line running from Jacob Rothschild through Ariane to Epstein.

Jacob initiates — drafting family governance letters, brokering introductions, offering to raise acquisition opportunities with bank CEOs.

Ariane executes and reports — every significant Jacob communication forwarded to Epstein’s inbox, usually with a one-line reaction.

Epstein manages downward — Ehud Barak, Larry Summers, the operational network — and reports upward to Ariane, who defers upward to Jacob.

The $25 million contract, the DOJ coordination through a former White House Counsel, and the systematic forwarding of confidential intra-family correspondence all run in the same direction: the family principal visible only through the intermediary’s forwards, the intermediary operationally present and signing contracts, the agent below managing intelligence and operations.

When Epstein was asked, he denied. On 30 August 2016, Boris Nikolic emailed him a two-word question: ‘Jacob Rothschild?’ Epstein replied: ‘No’. He denied knowing Jacob, yet sat on large amounts of Jacob’s forwarded emails.

Parallels

The parallels with Liedtke’s framework are visible in almost every element of the documented network.

Epstein was positioned in locations — New York, the US Virgin Islands, Paris — where the Rothschild banks did not maintain direct operational control but had significant interests. He gathered intelligence of the most privileged kind: Treasury meeting minutes forwarded by Peter Mandelson while serving as Business Secretary, advance notice of the €500 billion Euro bailout, strategic assessments of Rothschild inter-branch dynamics relayed to him by Ariane herself.

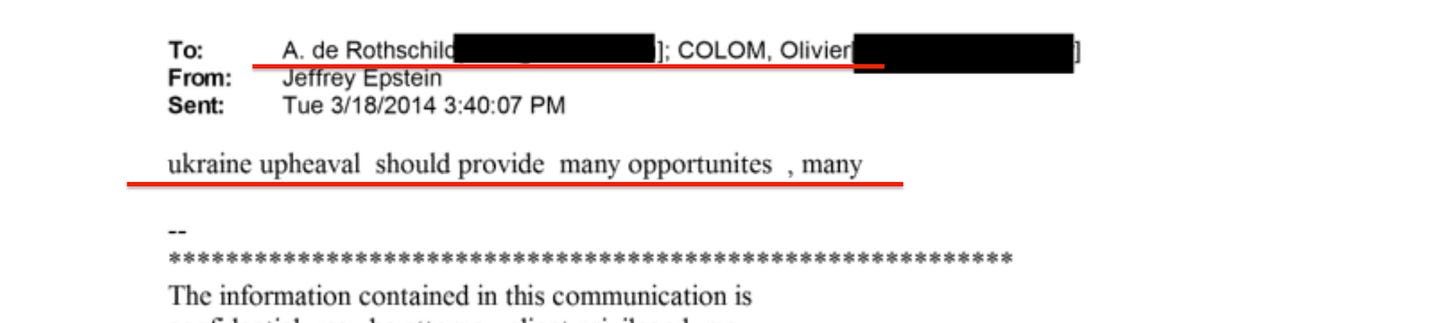

In March 2014, Ariane told Epstein she wanted to discuss Ukraine in an upcoming meeting; he replied that the upheaval ‘should provide many opportunites, many’6. This was the kind of political assessment that Liedtke describes as having replaced raw market data once the telegraph made commodity prices universally available.

He was compensated through access to deal flow and investment opportunities rather than a salary. The $25 million Rothschild contract was ostensibly for ‘risk analysis’ and ‘algorithm-related services’, with payment explicitly linked to outstanding matters between the Edmond de Rothschild group and US authorities. The $158 million in Leon Black advisory fees and the Wexner property transfer followed the same logic — each was payment for services within a specific domain.

The compensation model also functioned as a control mechanism. If an agent’s income depends entirely on continued access to the network’s deal flow, withdrawal of that access is equivalent to financial annihilation. The agent does not need to be explicitly threatened. The structure of the compensation ensures loyalty automatically, which is why disloyalty was, as Liedtke notes, ‘an extremely rare occurrence, because almost nobody wanted to put a usually profitable relation with the foremost financial dynasty of its time at risk’. The profitable dependency is the leash.

The first essay in this series described his funding model as deliberately distributed: ‘Ariane cannot use him if he belongs to Jacob. Summers cannot use him if he belongs to Ariane’. An agent funded by multiple parties and owned by none could route between them. Liedtke describes the identical arrangement in the nineteenth century: agents who were ‘open for offers from all bidders and not steeped in local intrigues’.

His lack of institutional affiliation served the same function as the ‘foreignness’ Liedtke identifies. Epstein held no government office, ran no bank, led no intelligence agency, held no academic post. His allegiance ran to the network, not to any national or corporate body within it.

The network around him was remarkably heterogeneous: Israeli military intelligence, British royalty, American Treasury secretaries, Silicon Valley founders, Yale network scientists, Latvian cryptographers, Mongolian presidents, Gulf sovereign wealth. Each node gave access to institutions and individuals the others struggled to reach — precisely the rationale Liedtke identifies for the Rothschilds’ deliberate recruitment across social, religious and national lines.

And the boundary held. Epstein was operationally essential, but he was never part of the inner circle — someone who ‘profited significantly from contacts to the Rothschild network’ while maintaining ‘business interests separately’.

The Belmont Problem

The Belmont problem also has its modern counterpart. When Epstein was denied his fee on the Gates-JPMorgan impact investing vehicle he had helped design, the correspondence shows his shift in behaviour. Draft emails appear in the archive containing allegations about Gates’s personal conduct and a fabricated resignation letter written in the voice of Boris Nikolic, Gates’s chief science adviser, confessing to complicity. Whether these were sent is secondary — their existence demonstrates Liedtke's identified vulnerability — the system's single recurring failure: the agent who accumulates enough independent knowledge to threaten the principals.

Belmont emancipated himself through distance. Epstein attempted to leverage himself through disclosure. The switchboard that knew what each node had done — because it had facilitated the connections — turned on the network when denied its fee.

Johann Rupert, the South African billionaire in direct business partnership with the Rothschild family since 1997, has stated publicly that Ariane ‘hid her relationship’ with Epstein from family business partners — the precondition for exactly the kind of leverage a disgruntled agent might attempt.

The attempt was never completed. On 29 July 2019, Epstein’s lawyers met with FBI and SDNY prosecutors and raised, in general terms, the possibility of their client’s cooperation. A cooperating Epstein would not have been a peripheral witness. He would have been the routing table documenting itself — every introduction, every strategic instruction, every intelligence flow mapped from the only position that saw all of them simultaneously. Twelve days later, he was found dead in his cell at the Metropolitan Correctional Center.

Belmont, operating at a distance that made control impossible, was tolerated. Epstein, operating at a distance that made cooperation possible, was not. The nineteenth-century resolution of the agent vulnerability was exile. The twenty-first-century resolution was permanent.

The Marriage Recruits

The marriage-recruit pattern documented by Liedtke, Kuper and Ferguson for the nineteenth century has direct contemporary parallels beyond Ariane de Rothschild.

Lynn Forester married Sir Evelyn de Rothschild in 2000, with the introduction reportedly facilitated by Henry Kissinger at the Bilderberg conference. She has since maintained an extraordinary public profile — from the Council for Inclusive Capitalism to the Vatican partnership with Pope Francis — operating as Liedtke describes: a link between the family’s interests and the institutions those interests seek to influence.

The correspondence between Lynn Forester de Rothschild and Hillary Clinton, documented in the Podesta and Clinton server emails, shows a reporting pattern similar to the Ariane-Epstein channel.

Marcus Agius is perhaps the cleanest example of the template in plain sight. In 1971, he married Katherine de Rothschild, daughter of Edmund Leopold de Rothschild of the English branch — a Roman Catholic marrying into the Jewish banking dynasty, matching the deliberate cross-religious recruitment Liedtke documents. After 34 years at Lazard, rising to chairman of the London branch and deputy chairman of Lazard LLC, Agius became chairman of Barclays in 2007.

Simultaneously, he served as chairman of the British Bankers’ Association, which administered LIBOR, as senior non-executive director of the BBC’s executive board, and as one of only three trustees of the Bilderberg Group. The scale of what a single marriage-recruit placement controlled warrants emphasis. LIBOR was the benchmark interest rate for an estimated $350 trillion in financial instruments globally — mortgages, derivatives, corporate loans, sovereign debt. Agius chaired both the bank that rigged the rate and the association that administered it7. A marriage recruit, living on the family estate at Exbury in Hampshire, occupied the position that set the price of global money while simultaneously chairing the body responsible for the integrity of the rate-setting process. He resigned as Barclays chairman in July 2012 following the manipulation scandal. His country home remains Exbury. The Rothschild Archive’s own website files his wife under her maiden name.

Hillary Clinton’s behaviour suggests a similar position — positioned on both sides of the impact investing pipeline, setting the standards, approving the OPIC tranche, and benefiting from the flow.

Stern’s Bleichröder ran a branch office in Berlin of the Rothschild banking house while serving as Bismarck’s personal financial agent. Agius chaired Barclays while living at the family estate. The marriage, the placement at a major financial institution, the accumulation of positions across finance, media and transatlantic policy, and the residence on Rothschild property are all matters of public record.

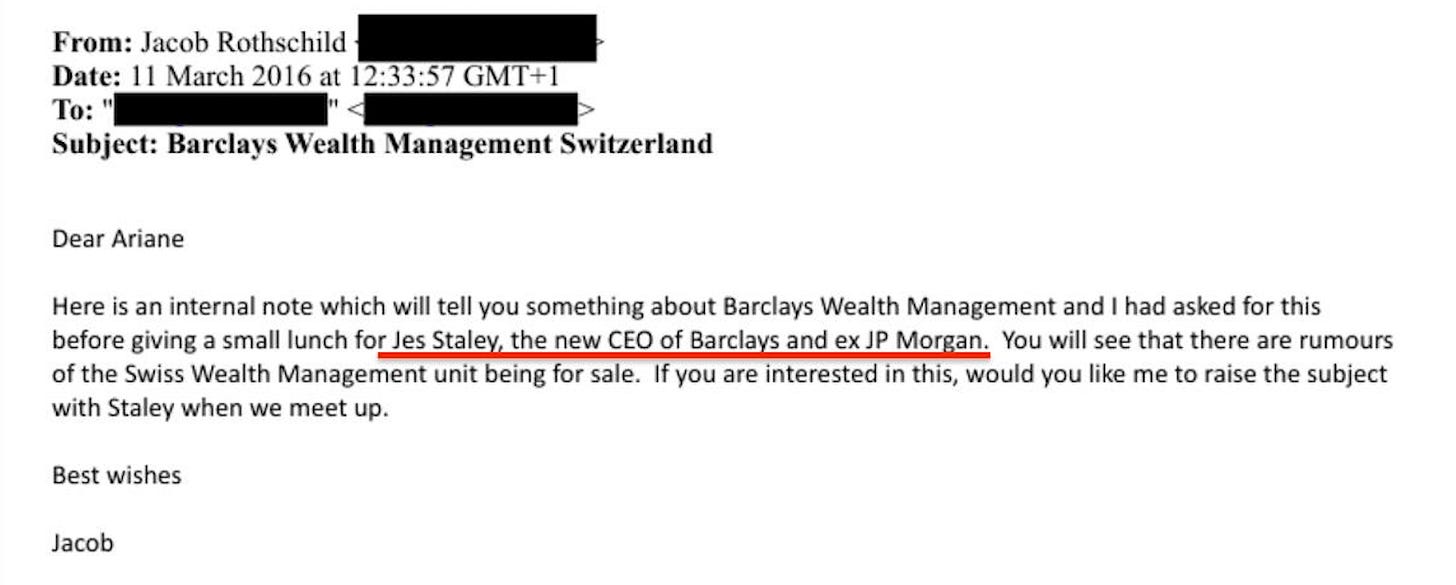

Jacob Rothschild also maintained a direct relationship with Barclays leadership independently of the Agius connection — his March 2016 email to Ariane mentions lunching with Jes Staley8, who became Barclays CEO in 2015 — suggesting redundant paths into the same institution across different periods. The redundancy is consistent with the method. You verify assets you do not fully control by maintaining more than one route to them.

The Long-Service Path

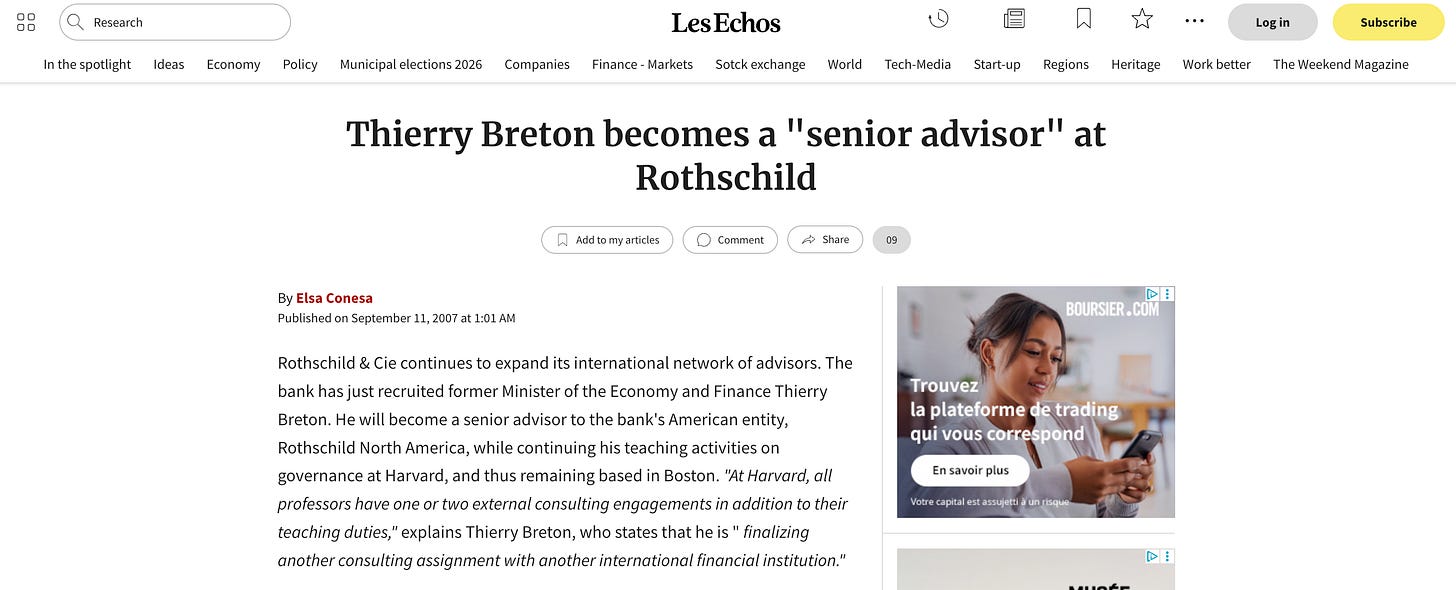

Marriage, however, was only one of Liedtke’s two recruitment paths. The second — long service within the house — also has contemporary candidates. Wilbur Ross spent twenty-four years at Rothschild Inc. in New York before becoming US Commerce Secretary9. Emmanuel Macron worked at Rothschild & Cie Banque before entering the Élysée and the presidency10. Thierry Breton served as a senior adviser at Rothschild & Cie — a detail he omitted from his EU Commissioner CV — before taking charge of the European Commission’s internal market portfolio11.

In Britain, John Redwood moved from head of Margaret Thatcher’s Policy Unit to a directorship at N.M. Rothschild12; Oliver Letwin followed the same path, succeeding Redwood before returning to government as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster13. The Spectator noted the pattern as early as 1988, listing Rothschild alumni across Downing Street and the Treasury and observing that the bank’s privatisation expertise14 — developed advising the British government — was then exported to Spain, Malaysia, Singapore, Chile and Turkey.

And the heterogeneity criterion has its own specimen. Klaus Mangold, a German industrialist with no family ties, chaired both Rothschild GmbH and Rothschild Russia & CIS for more than a decade while serving as Honorary Consul of the Russian Federation15. Known in the German press as ‘Mr Russia’, he facilitated the Paks II nuclear project between Hungary and Rosatom, entering rooms in Moscow and Budapest that no Rothschild could.

The firm’s public alumni roster lists, among others, a former French president, a former German chancellor, a former governor of the Bank of England, and a former US commerce secretary.

The nineteenth-century agents operated within the family’s private banking network. Their twentieth and twenty-first-century successors operate within the institutional architecture that absorbed and replaced it — the central banks, the multilateral bodies, the regulatory commissions, the sovereign governments that now perform at state level what the Rothschild houses once performed privately. Ross at Commerce, Macron at the Élysée, Breton at the European Commission — these are not placements into the family’s business. They are placements into the institutions that now carry out the family’s historical function at sovereign scale. The agent register, it would appear, has not grown shorter with time16.

The Living Statement

David de Rothschild has stated publicly that he is the only Rothschild permitted to conduct banking17. This is not a historical observation. It is a living member of the family restating Liedtke’s core finding — that only born Rothschilds were fully trusted and that the essential criterion for a Rothschild bank existing in a given location was whether a born Rothschild was willing to be there — in the present tense, as current policy. That is not a parallel with the nineteenth-century method. It is continuity, stated by the family itself.

The marriage recruits, however prominent, remain outside.

The Recurring Architecture

The three-tier structure Liedtke documents — inner circle, trusted agents, everyone else — is not unique to the Rothschild network. It recurs with striking consistency across every governance architecture examined in this series, and its recurrence across such different domains suggests something more fundamental than coincidence or imitation.

In the system of ratification theatre, technical committees write the rules, finance ministers and secretariats transmit them, and elected leaders rubber-stamp what has already been decided. The technical committees never answer to the general assembly. The general assembly never rewrites the technical standards.

In the Noahide framework documented in Cohen’s Religion of Reason and developed in Laitman’s teachings, the structure is explicitly not ethnic. Laitman redefines ‘Israel’ as a state of consciousness achieved through correction of egoism — anyone who completes the process becomes ‘Israel’ regardless of ethnicity or geography.

Most actual Israelis would not qualify under his definition. The top tier consists of only those who fully internalise the governing ethic, the second tier of those who accept the basic code, and the third of those who refuse both and are excluded from ‘inclusive capitalism’.

In Burstein and Negoita’s Kabbalah System Theory — applied in artificial intelligence research as a model for layered decision-making — the cognitive layer defines standards and truth, the evaluative layer assesses compliance, and the behavioural layer executes.

The evaluative layer rarely reaches the cognitive layer. It generally only applies what has been handed down. Issue a ‘complex global shock’ predicted by ‘black box’ modelling under the UN Emergency Platform, and all feedback is eliminated.

The switch to top-down emergency governance is automatic.

The pattern holds at every scale. The inner circle sets the standard. The middle tier operates within it and enforces it. The outer tier complies or faces exclusion. The critical boundary — the one that rarely opens — sits between the first tier and the second.

The significance of this lies in what happens when you observe the architecture remaining constant while the governing ethic changes. From religious law to environmental stewardship to sustainable development to financial stability to public health — the ethic rotates, but the structure does not. If the architecture persists while the content it governs is interchangeable, then the content is not the point. What matters is who occupies the cognitive position: the translation layer that converts whichever ethic prevails into operational standards that the tiers below must follow.

The climate scientist genuinely believes they are preventing catastrophic warming. The AI researcher genuinely believes they are making disclosure more efficient. The central banker genuinely believes programmable payments serve financial inclusion. They need only see their own component. The people who see the full assembly operate through informal channels that produce no working papers, publish no documentation, and answer to no parliament.

What the Sources Say

None of this constitutes proof of a direct, conscious replication of the Liedtke model. The Rothschild Archive has not released correspondence from the late twentieth century, and the family’s contemporary operations are conducted through corporate structures rather than the personal networks Liedtke documented.

What can be said, on the basis of published academic research, is that the Rothschild family operated an agent network for over a century using a method with a clearly defined structure — and that the network visible around Jeffrey Epstein exhibits those same characteristics in considerable detail.

The recruitment, the intelligence, the compensation, the heterogeneity, the public visibility, and the permanent exclusion from the inner circle all align. So does the single recurring vulnerability: the agent who knows too much. And so does the resolution of that vulnerability — though the modern version is considerably more final than anything Liedtke detailed in the archive.

Liedtke concludes his paper with an observation about loyalty:

… very few business partners or agents dared to cross the Rothschilds. Disloyalty was an extremely rare occurrence, because almost nobody wanted to put a usually profitable relation with the foremost financial dynasty of its time at risk.

Jeffrey Epstein is not around to give evidence. But the method — documented across two centuries by four independent academic studies — requires no speculation at all.

It is simply what the sources say.

The Cockpit

In October 2019, CNN profiled David de Rothschild — son of Sir Evelyn, whose wife Lynn Forester runs the Council for Inclusive Capitalism and the Vatican partnership with Pope Francis — as the navigator of ‘Spaceship Earth’. An environmental explorer. A sustainability advocate. Founder of a lifestyle brand. Ambassador for the UK government’s Year of Green Action. Working with the UN, National Geographic, the World Economic Forum. ‘I think, predominantly, I’m just David’.

In December 2025, the Network for Greening the Financial System announced an ‘independent’ scientific advisory committee to oversee the climate scenarios that calibrate global banking capital requirements. No members were named and no terms of reference were published.

The scenarios it will validate are produced by a consortium funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies and the ClimateWorks Foundation. The disclosure framework that created demand for those scenarios was chaired by Michael Bloomberg. ClimateWorks sits on the advisory council that organises scenario production for the IPCC. The same philanthropic entities fund the science, the disclosure standards, the research network, and the regulatory guidance — and through programmable CBDC pilots now operational in over a hundred countries, the architecture extends from scenario to individual transaction.

The governing ethic of the moment is sustainability. The structure is the three-tier architecture documented across two centuries by four independent academic studies. The navigator is in plain sight, and so is the cockpit.

Liedtke’s framework leaves only one question open — whether the passengers were ever told where the ship is going.

Makes every spy story written since Buchan's--not Hitchcock's--*39 Steps* look naive.

You're going for it now aren't you.

A systems analyst, reverse engineering a vampire operation is not going to be short on systemic planning himself.

Well planned.

Your previous essays are stakes being sharpened. Your anonymity a garlic necklace.

Fucking loving this esc.