Ethica

In the spring of 2000, the Earth Charter1 was launched at the Peace Palace in The Hague. It reads like a planetary constitution, a statement of shared values for a world facing ecological crisis. ‘We stand at a critical moment in Earth’s history’, it begins, calling for ‘a sustainable way of life’ grounded in ‘respect for nature, universal human rights, economic justice, and a culture of peace’.

Behind those words lies a three-century philosophical lineage that begins with Baruch Spinoza’s Ethica2: the belief that ethics can be derived from an immanent nature, not imposed from the outside.

But Spinoza’s world is based on predictability, and that leaves a question: is it possible to retain free will in a world based on Spinoza’s Ethics?

What’s remarkable is not just what it says, but how it came to be possible to say it. Behind the Earth Charter lies a centuries-long philosophical project: the construction of ethical monism3, the idea that there is one reality, knowable by one method, yielding one overarching framework for how we ought to live. This is not mysticism or totalitarian thinking, but a belief that ethics can be grounded in how the world actually works, that morality can be immanent rather than imposed from outside, and that humanity can discover shared principles not by decree but by understanding our place in nature.

The story of how we got here winds through three centuries of philosophy, science, and systems thinking. It begins with a lens grinder in 17th-century Amsterdam and ends with global governance frameworks for the 21st century. Along the way, it touches radical thinkers, revolutionary movements, cybernetics labs, and interfaith dialogues. This is the story of ethical monism.

Executive Summary

The contemporary architecture of planetary governance traces a direct lineage from Baruch Spinoza’s 17th-century philosophy to today’s operational systems. Spinoza collapsed the distinction between God and Nature, arguing that ethics could be derived from understanding reality itself rather than imposed by external authority. This vision of ‘immanent ethics’ — morality emerging from within the natural order — evolved through three centuries of intellectual development. Paul Carus anchored it to scientific method in the 1890s, arguing that universal ethics could be grounded in scientifically knowable law. Alexander Bogdanov provided the organisational framework through his ‘tektology’, claiming that principles governing system health could dictate how human societies should organise. The systems theorists of the mid-20th century (Bertalanffy, Boulding, Churchman) delivered the analytical methods, while cyberneticians (Leontief, Beer, Forrester) built the computational infrastructure. This culminated in the Earth Charter (2000), a planetary constitution grounding ethics in scientific understanding of ecological limits.

This philosophical vision now operates as concrete infrastructure. The International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) produces integrated assessment models that trace how policy choices cascade through interconnected planetary systems. The Planetary Boundaries framework defines nine ‘safe operating space’ thresholds, claiming six have already been transgressed. Multi-regional input-output tables track global supply chains down to individual transactions. These models inform binding international frameworks: the UN’s Pact for the Future coordinates responses to ‘Global Complex Shocks’, the proposed Emergency Platform would trigger coordinated interventions based on model-identified crises, efforts to criminalise ‘EcoCide’ through the International Criminal Court would prosecute environmental harm, and proposals to eliminate Security Council veto power would enable global military enforcement. Simultaneously, programmable central bank digital currencies are being designed to enforce compliance at the transaction level — your payment clears only when validators confirm alignment with sustainability requirements. The same ethical imperatives that justify Security Council resolutions are being embedded into money itself.

The architecture concentrates power while eliminating accountability. Climate models simulate a minuscule fraction of atmospheric particles and repeatedly fail to predict regional weather patterns, yet their outputs drive trillion-dollar policies. When models are wrong no one faces consequences. Modelers claim failures prove insufficient surveillance data, politicians defer to ‘best available science’, funders invoke ‘humanitarian necessity’, and religious authorities frame compliance as sacred duty. Each actor deflects responsibility to another part of the system. The models are opaque ‘black boxes’ requiring specialised expertise to audit — expertise concentrated in the same institutions producing them. Dissent becomes functionally impossible when ‘the science’ is embodied in simulations only credentialed experts can interpret, and those experts work for the institutions claiming emergency authority.

This represents administrative monism with no possibility of appeal. When the same ethical framework embedded at every scale there exists no institutional layer outside the system for contestation. Spinoza’s philosophical determinism becomes operational reality: choice is removed by design, understanding becomes irrelevant because the architecture decides for you, and human judgment is displaced by algorithmic processing.

The system eliminates free will not through philosophical argument but through infrastructure — automated compliance where ‘knowledge of nature’ has been monopolised by institutions that define nature through unverifiable models, then enforce their definitions through protocols operating below conscious deliberation.

Whether this architecture emerged through intentional design or institutional evolution matters less than recognising what constrains it once fully operational:

Nothing.

Bringing God Inside the World

Baruch Spinoza, working in the Netherlands in the 1660s and 70s, collapsed the distinction between God and Nature. For Spinoza, there was no divine lawgiver standing outside creation, handing down commandments. Instead, God and Nature were the same thing, a single substance expressing itself in infinite ways. Humans were not separate from this order but part of it — modes of Nature itself.

This had explosive implications. If there’s no external authority, where does morality come from? Spinoza’s answer: from within the system. Every being has ‘conatus’, a drive to persist and flourish. Human flourishing comes through reasoning, with a clear understanding of how we fit into the larger order. When we understand our nature properly, we experience joy and what Spinoza called ‘the intellectual love of God’, which is really love of reality itself. Cooperation and peace become rational because they increase our power of acting in the world.

This is immanent ethics: moral authority located inside the world rather than imposed from outside. There’s still a gradient, still a direction for improvement, but it’s built into the nature of things. You don’t need revelation; you need understanding. This is the foundation of ethical monism, the idea that how we ought to live can be derived from how things actually are.

Carus and the Religion of Science

Two centuries later, in the 1890s America, a German-born philosopher named Paul Carus took Spinoza’s project and gave it a new anchor. Carus ran the Open Court Publishing Company in Illinois, a remarkable operation that translated Eastern philosophy, published scientific monographs, and hosted interfaith dialogues4. The 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions5 met in Chicago, bringing together Buddhists, Hindus, Christians, and free-thinkers in unprecedented conversation. Carus was at the center of it all.

His idea was what he called ‘The Religion of Science’6. Carus wanted to keep the religious function — the sense of unity, meaning, and ethical purpose — but root it in scientifically knowable law rather than divine revelation. He wasn’t alone in this: Ernst Haeckel’s Monist League in Germany and Auguste Comte’s positivism in France had already been pushing similar visions of scientific naturalism as moral foundation. But Carus gave it a distinctive interfaith dimension. Ethics becomes living in alignment with reality as disclosed by systematic inquiry. This is still Spinoza’s immanence, but now the anchor has shifted from ‘God or Nature’ to ‘Nature as revealed by Science’.

This carries significant implications. If science is universal, and ethics flows from scientific understanding, then ethics becomes universal too. One reality, one method of knowing it, one overarching framework for living well. This is ethical monism with a modern infrastructure: not religious dogma but scientific consensus as the arbiter of how things are, and therefore of how we should act.

Carus’s project intersected with other movements of his era. Marx and Engels’ Scientific socialism claimed to have discovered the laws of historical development, suggesting that human emancipation meant aligning with history’s scientifically graspable direction7. The progressive movement sought to apply rational planning to social problems. All shared the conviction that clear understanding of reality could yield clear guidance for action.

Bogdanov’s Organisational Turn

In revolutionary Russia, another thinker was pushing ethical monism in a radical new direction. Alexander Bogdanov, a physician, philosopher, and Bolshevik who later broke with Lenin, developed what he called ‘empiriomonism’ and ‘tektology’89. These unwieldy terms concealed a powerful insight.

Bogdanov argued that truth wasn’t a mirror of some external reality but a collectively organised experience, shaped by practice and labor. What we call ‘facts’ are really stable coordination points for human activity. This sounds abstract, but it had an ethical punch: if truth is organised experience, then the good is whatever organisation increases collective power and viability. Ethics becomes organisational ethics.

Tektology, Bogdanov’s later project, was meant to be a universal science of organisation10. How do complex systems maintain themselves? How do they adapt and grow? What principles govern the organisation of everything from cells to economies? Bogdanov believed you could extract general laws that applied across nature and society, and these laws would tell you how to organise human affairs for maximum flourishing.

This was Carus’s scientific monism, but now it had a method. You could study how systems actually work and derive principles for how human systems should work. The Proletkult11, Bogdanov’s educational movement, aimed to train workers in this kind of systems thinking — it was pedagogy and praxis, not a moral code but a way of cultivating the perception and judgment needed to navigate organised complexity. The goal was creating a new kind of cognitive and ethical subject capable of managing an increasingly complex world.

Bogdanov never completed his synthesis. He died in 1928 from a blood transfusion experiment on himself12. But his ideas about organisation, systems, and collective coordination seeded what would become the cybernetic and systems movements of the mid-20th century.

The Systems Tradition

After World War II, a new intellectual constellation emerged around the idea of systems. Ludwig von Bertalanffy, an Austrian biologist, proposed General Systems Theory13: the idea that you could find common patterns across disciplines. Open systems, feedback loops, homeostasis — these concepts appeared in biology, engineering, economics, and psychology. Maybe there really was a universal science of organisation.

Kenneth Boulding — an economist and Quaker, who later penned ‘The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth‘14 — added structure to this vision with his ‘Skeleton of Science’ hierarchy of system levels15. From static frameworks to clockworks to thermostats to cells to plants to animals to humans to social systems to transcendental systems — each level had its own logic, but you could see a hierarchical continuity. This gave ethical monism a scaffold. We’re not just imposing human values on the world; we’re recognising different kinds of complexity and figuring out which principles apply where.

Another important development came from C. West Churchman, a systems philosopher who insisted that ethics had to be built into systems practice from the start16. Churchman developed what he called ‘the sweep-in’: when you design a system, you have to keep expanding your boundary to include everyone affected by it. You can’t draw arbitrary lines around ‘the problem’. Every system design is an ethical choice about who counts and what values you’re serving.

Here’s the issue: systems will now encode the ethics of their parent systems. A corporate supply chain inherits the values embedded in trade law; a city’s water system reflects national infrastructure priorities; an AI model encodes the objectives of its training regime. This creates a hierarchy of ethics. If systems affecting the world need coherent ethics to avoid contradiction and conflict, those ethics must be set at the global level. This is the architectural drive toward ethical monism at the systems level — not just a philosophical preference, but a structural necessity for planetary coordination. One interconnected system requires one ethical framework at the top, embedded into every application of systems theory and hence into every application of adaptive management.

Finally, Erich Jantsch, an Austrian astrophysicist and systems theorist, made the structure explicit. In his 1970 work on the ‘Inter- and Transdisciplinary University’17, Jantsch laid out a four-level hierarchy: empirical at the bottom (natural sciences), pragmatic above it (social sciences), normative next (ethics and standards), and purposive at the top. This is the architecture of ethical monism rendered as a Thomistic, institutional design. Purpose leads to ethics; ethics leads to systems theory; systems theory governs application. The normative layer doesn’t emerge from the empirical — it flows down from purpose. This inverts the usual story that ‘science discovers facts, then we decide what to do with them’. Instead we set purpose, derive ethics, then deploy systems thinking to achieve those ends. Jantsch gave ethical monism its operating manual.

The Infrastructure: Making It Concrete

While philosophers were developing systems theory, others were building the concrete infrastructure that would make planetary-scale ethical thinking possible. This is where the abstract ideas touched ground.

Wassily Leontief, a Russian-American economist, developed input-output analysis18, a way of mapping how resources flow through an economy. Every industry uses inputs from other industries and produces outputs that others use. Leontief showed you could capture this in matrices and trace ripple effects through the whole system. The intellectual genealogy runs deep here — from Quesnay’s Tableau Économique19 through Walras’s general equilibrium and Marx’s reproduction schemas20 — but Leontief made it operational and empirical. This was accounting for interconnection, and it turned out to be incredibly powerful.

Input-output analysis became foundational for global modeling. Extended to multi-regional input-output (MRIO) tables21, you could trace supply chains across borders: your smartphone’s cobalt from Congo, its assembly in China, its shipping emissions, the electricity for data centers — MRIO reveals the full consumption-based footprint. You could track carbon emissions, water use, labor hours through global production networks. You could model planetary boundaries and resource limits. Suddenly the abstract systems concepts had numbers attached. You could see the interdependence Spinoza and Carus had talked about, rendered in quantities and flows.

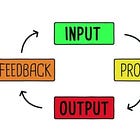

At the same time, cybernetics — the science of communication and control in systems — provided the feedback machinery. Norbert Wiener22 and W. Ross Ashby23 showed how systems maintain stability through information flows. The key insight: feedback loops everywhere. Build more road lanes to ease congestion, and induced demand brings more traffic. Subsidise a resource, and consumption rises to meet the cheaper price. These aren’t bugs; they’re how systems work. Stafford Beer applied this to organisations with his Viable System Model24, showing how autonomy and coordination could coexist in recursive structures. Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela developed autopoiesis25, the idea that living systems are fundamentally self-creating and self-maintaining.

Jay Forrester and Donella Meadows brought systems thinking to global challenges with system dynamics and the famous Limits to Growth report in 197226. For the first time, you could build computer models of planetary systems and ask: what happens if we keep growing like this? The answer was perhaps sobering, but the methodology was powerful. You could make immanent ethics concrete: here are the boundaries reality imposes, here’s how the system responds to different choices.

This infrastructure converged in institutions like the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA)27, where integrated assessment models — MESSAGEix for energy systems28, GLOBIOM for land use29 — became the workhorses that turn systems theory, input-output accounting, and feedback loops into actual policy pathways. These models integrate climate, energy, land, and food systems, tracing how choices in one domain cascade through others: how energy choices affect food systems, how land-use changes influence climate, how different scenarios play out across decades. They’re the machinery that makes ethical monism operational: one reality, mapped in detail, yielding concrete trade-offs for decision-makers. Planetary Boundaries would later define risk thresholds; these integrated assessment models supposedly determine whether we’re within limits.

From Interfaith to Global Ethics

While all this scientific and systems infrastructure was developing, something else developed in the cultural sphere. The interfaith movement that Carus had participated in didn’t disappear30. It evolved into a broader search for shared values across cultures and traditions.

Remarkably, 1893 — the year of Carus’s World’s Parliament of Religions — also saw Thomas Henry Huxley deliver his famous Romanes Lecture on ‘Evolution and Ethics’31. Darwin’s great champion was grappling with the same question from another angle: if humans are products of evolution, how do we ground morality? The Huxley family would return to this problem across three generations. Aldous Huxley, T.H.’s grandson, wrote ‘The Perennial Philosophy’32 in 1945, an early attempt to distill universal wisdom from diverse spiritual traditions — proto-global ethic.

Julian Huxley, another grandson and a biologist who became UNESCO’s first Director-General, carried the project into institutional form. He founded the International Humanist and Ethical Union33 in 1952, creating an organisational home for scientific humanism as a global ethical framework. He wrote the foreword to Teilhard de Chardin’s ‘The Phenomenon of Man’34, championing Teilhard’s vision of cosmic evolution toward greater consciousness and unity. The Huxleys kept circling back: how do you build ethics from evolutionary understanding? How do you find universal principles in a world of change?

Teilhard represents the spiritual flank of this whole project. A Jesuit paleontologist, he recast Spinoza’s immanence as cosmic evolution, moving from matter to life to consciousness to what he called the ‘noosphere’ — a collective mind layer emerging from the biosphere — and ultimately toward an ‘Omega Point’ of unity and integration35. This is ethical monism with a narrative arc: not just ‘here’s how things work’ but ‘here’s where things are going’. The noosphere gives planetary coordination a motivating story, a telos emerging from within evolution rather than imposed from outside. Ethics becomes responsibility for the ascent, stewardship of consciousness itself. Through Julian Huxley’s UNESCO and the broader evolutionary humanism movement, Teilhard’s vision bled into postwar thinking about global cooperation and shared human destiny.

In 1993, exactly one hundred years after Carus had helped convene the original World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago, the centennial Parliament gathered again. Two scholars, the Catholic theologian Hans Küng and the interfaith pioneer Leonard Swidler, brought forward a Declaration Toward a Global Ethic36. Küng had been working on this for years, convinced that ‘no peace among the nations without peace among the religions’. Swidler extended the work in his 1995 report37, building a layered structure: a global ethic at the top, rights balanced against responsibilities in the middle layer, and collectivism as the foundational principle. This was architectural thinking applied to ethics itself.

The 1993 Declaration identified commitments that appeared across traditions: non-violence, justice, truthfulness, respect between genders — recognising that different traditions had arrived at overlapping principles because they were all grappling with the same human realities. The direct line from Carus’s 1893 gathering to Küng and Swidler’s 1993 work shows how the interfaith project had matured: from dialogue and mutual understanding to articulating shared ethical foundations.

The Earth Charter38, launched in 2000, represented the culmination of this parallel track. It brought together the systems perspective and the interfaith ethical work. Its four pillars — respect and care for the community of life, ecological integrity, social and economic justice, and democracy, nonviolence, and peace — weren’t arbitrary. They reflected both scientific understanding of how planetary systems work and normative consensus about what mattered across cultures.

The Earth Charter is ethical monism made practical. It assumes one universal, interconnected reality (the scientific picture), derives principles from that reality (respect for nature’s limits), and articulates these as universal values (human rights, ecological responsibility, economic fairness, peace). It’s Spinoza’s immanent ethics plus Carus’s scientific foundation plus Bogdanov’s organisational logic plus the systems tradition’s analytical power, all wrapped in language that speaks across cultures.

Contemporary proposals like the Global Pact for the Environment39 — still advancing through international negotiations with partial uptake — aim to take the next step: elevating these principles from aspirational charter into binding international law, sometimes described as building blocks toward a planetary constitution40.

The Power and the Risk

By 2009, Earth system scientists had formalised what these models were targeting: the Planetary Boundaries framework41. Nine (supposedly) critical thresholds — climate change, biodiversity loss, nitrogen cycles, ocean acidification, and others — define a ‘safe operating space for humanity’, and never mind that they in 2015 knew ‘novel entities’ were significant beyond thresholds without being fully quantified. Updated assessments in 2023 claim we’ve (supposedly) already transgressed six of nine boundaries. That same year, the Earth Commission42 pushed further with ‘safe and just’ boundaries that account for human wellbeing alongside ecological limits43.

This is where the architecture becomes precarious. These boundaries are extraordinarily difficult to determine with any certainty — they rest on global models like IIASA’s integrated assessments, which operate as opaque ‘black box’ systems without democratic oversight. Responsibility diffuses into complex model assumptions, parameter choices, and scenario definitions that few can scrutinise. The boundaries provide a risk canvas — a quantified Abyss — but one that could easily be manipulated. Who sets the thresholds? Who validates the models? Who tunes the epsilons? Who decides what counts as ‘transgression’? The models trace pathways; the boundaries mark supposed cliff edges. But the cliff edges themselves are model outputs with major imprecision issues — not observable facts.

The governance logic that emerges follows what environmental scientists call adaptive management — the cycle of measure → model → act → learn formalised by CS Holling and colleagues in the 1970s44. But see how the pieces fit together: general systems theory supplies the model, global surveillance provides the data for input-output analysis, and policy response closes the cybernetic loop. You don’t solve these problems once; you continuously iterate, updating policy as new data arrives. This justifies treating planetary coordination as an ongoing process rather than a one-shot fix — adaptive management, in effect. This also justifies continuous monitoring, measurement, and intervention — adaptive management as permanent supervision.

At the administrative level, McNamara’s PPBS embodies this as plan → program elements → budget → evaluate → reprogram — with immanent correction through metrics and policy feedback, not external decree.

This lineage delivered a framework for planetary coordination grounded in purported understanding rather than imposed authority. When nations negotiate climate treaties, when scientists model tipping points, when civil society groups demand environmental justice, they draw on this synthesis.

There’s one atmosphere, one set of biogeochemical cycles, one reality we all inhabit. Science can map that reality, systems thinking can model its dynamics, and ethical principles can be derived from those constraints — or so the ‘experts’ claim.

But this carries inherent risks. The architecture enables ‘one reality, one method, one ethic’ to harden into ‘one right answer, administered by experts, with no room for dissent’. Science can assert we’re exceeding planetary boundaries, but it cannot determine how to distribute the costs of staying within them. Models can project potential futures, but they cannot judge accurately between different visions of what a good life entails. Liberty, equality, prosperity, even duration of life itself — these values often conflict, and no amount of systems modeling resolves the tension.

The neo-Kantian Hermann Cohen argued for universal ethics grounded in reason45. His ‘Ethics of the Pure Will’ insists that the ‘ought’ cannot be read off from the ‘is’. Ethics is primary, a legislative act of practical reason, not an inference from data. Meanwhile, Cohen frames justice as an ‘infinite task’, an unending approach to the ethical ideal that can never be finally achieved, but rather requires a continuous synchronisation of law and ethics.

But does this constrain the architecture, or legitimise it? If the systems models, data infrastructure, and institutional power remain unchanged, adding ‘we need practical reason to legislate’ provides philosophical cover without altering power distribution. Cohen’s ‘infinite judgment’46 could justify permanent iteration — continuous modeling, monitoring, adjustment — rather than limiting the framework’s reach.

The Earth Charter presents itself as open and pluralistic, acknowledging individual rights and collective responsibility, economic development and ecological limits, cultural diversity and universal principles47. Yet the openness is carefully bounded. The paths all operate within the same systems architecture, use the same modeling infrastructure, accept the same planetary boundaries as given.

Rival models require funding, expertise, and institutional legitimacy — all concentrated in the same global modeling centers. Rights constraints are typically reinterpreted when ‘planetary emergencies’ are invoked48. The framework has learned to absorb critique, presenting flexibility as evidence of legitimacy rather than a limitation of power. What appears as ‘mature ethical monism’ appears to be a more sophisticated version that has learned to accommodate dissent without relinquishing control of the architecture itself.

Conclusion

The path from Spinoza to the Earth Charter is the story of ethics relocating from heaven to questionable scientific inquiry. It’s the belief that we can ground our values in how things suppoedly work, that cooperation and care are fundamentally rational.

Three hundred and fifty years after Spinoza wrote his Ethica, we have tools he couldn’t have imagined: global data networks, climate models, input-output matrices, systems dynamics software. We can see the whole Earth system in ways that would have astounded Carus and thrilled Bogdanov. We can model futures, track flows, measure feedback, and even program computers to respond automatically without the need of a human operator.

And now the architecture is operationalising. The United Nations’ Pact for the Future49, adopted in 2024, represents the latest attempt to retool global governance around shared risks — climate disruption, public health, biodiversity collapse, the rights of future generations. But how the pieces happen to assemble tells its own story:

Models determine a crisis. IIASA’s assessments predict incoming catastrophe. Planetary Boundaries mark transgression points. Pope Francis’s Laudato Si’50 (2015) and Laudate Deum51 (2023) frame ecological crisis in language that echoes these scientific models — translating global ‘black box’ modelling outputs into moral imperatives for 1.3 billion Catholics.

Emergency authorities are being constructed. The UN’s proposed Emergency Platform would integrate ‘Global Complex Shocks’52 — the very scenarios ‘black box’ models produce — into grounds for declaring emergencies and triggering coordinated responses. The framework presents itself as reactive, responding to crises, rather than as the architecture that defines what even counts as crisis.

Enforcement mechanisms are being established. The push to recognise Ecocide as an international crime53 prosecutable by the International Criminal Court54 would criminalise large-scale environmental harm. Proposals to integrate this with the Security Council55 would enable the prescription of military force against nations deemed to be destroying nature. Concurrent efforts to eliminate the Security Council veto56 would remove the ability of major powers to block such interventions.

The ‘Right to a Healthy Environment’57 guarantees environments that are ‘ecologically healthy, regardless of direct impacts on people’58. This is a remarkable shift: rights for nature independent of human use, enforceable through the same institutional machinery. Nature overriding the needs of humans, as predicted by ‘black box’ models.

Health authorities create parallel powers. The Pandemic Treaty59 operates through One Health60 provisions that explicitly conflate environmental health with human health. This means environmental conditions defined by ‘black box’ models can trigger public health emergencies under claims of ‘zoonotic’ pandemic potentials, modelled by more ‘black box’ models, in theory justifying lockdowns, school closures, movement restrictions, resource controls — as witnessed during Covid. The architecture doesn’t just respond to pandemics; it gains authority to manage the environmental conditions it claims produce them.

The IIASA models identify thresholds → Emergency Platform declares crisis → One Health provisions enable health emergency powers → Ecocide prosecution criminalises resistance → Security Council (without veto61) authorises force. Each piece appears reasonable in isolation, but together they form an architecture where model outputs can cascade into emergency authorities and ultimately enforcement — and should any nation object, the Security Council could hypothetically prescribe the use of force.

But the system doesn’t stop at traditional state power. The same ethical imperatives — the same planetary boundaries, the same sustainability requirements, the same claimed moral necessities — are being simultaneously embedded into money itself. Through the language of ‘inclusive capitalism’ — Lynn Forrester de Rothschild’s Council for Inclusive Capitalism with the Vatican62 — and the infrastructure of programmable central bank digital currencies, the Bank for International Settlements and major central banks are building payment systems where transactions clear only when validators confirm compliance with these same ethical objectives.

Carbon credentials verified through CBAM, digital product passports checked, conditions met. The payment either completes or it doesn’t, automatically, at the protocol level. All, pretending to be about ‘ethics’.

This is the ‘moral economy’ operationalised: a unified control apparatus where the same ethical framework can soon justify Security Council resolutions authorising military force, financial protocols that decline your transaction, and religious authorities issuing moral imperatives to comply.

State power, market access, emergency authorities, everyday commerce, papal encyclicals and financial infrastructure — all governed by the same ‘black box’ model outputs, all enforcing the same claimed ‘ethical’ imperatives derived from modelling known to be less than precise.

The system wraps itself in ethics — planetary stewardship, human rights, collective responsibility, care for creation — while building enforcement mechanisms at every level from international law right down to individual purchases through CBDCs. Religious leaders provide the moral legitimisation, politicians defer to ‘the science’, modelers claim insufficient capacity, funders act ‘for the common good’, and the financial system executes automatically.

No emergency is even needed for the latter. Just silent, automated denial of economic access, blessed by religious authority and justified by the same moral language that legitimises everything above it.

But observe what this system actually does. The models are imprecise. Atmospheric simulations model a minuscule fraction of the total particles on the planet, and they repeatedly fail to predict hurricanes6364, never mind tornados.

Climate projections rest on assumptions about feedback loops, tipping points, and system responses that remain poorly understood. The models are frequently wrong — yet when they are, no one is accountable. They can destroy lives and enterprise, yet there is no mechanism for holding modellers responsible when predicted catastrophes — such as those predicted by Neil Fergusons dubious source code — fail to materialise, or when interventions based on their outputs cause direct harm.

The accountability vacuum is carefully maintained. Modellers claim imprecision results from insufficient surveillance data, using failures as justification for more infrastructure — streaming satellite surveillance65, mobile phone data collection, PCR lab results, citywide IoT sensors, or perhaps more computational power for Digital Twin simulations. Politicians claim they merely ‘follow the best available science’, deferring to experts while disclaiming responsibility for outcomes.

Funders — foundations, development banks, multilateral agencies — claim they act ‘for the common good’, placing their interventions beyond scrutiny by appealing to humanitarian necessity. Religious leaders issue calls to ‘care for the planet’ as demanded by sacred texts, framing compliance as moral duty and resistance as sin against creation. Each actor deflects responsibility to another part of the system.

The models need better data, the politicians follow the models, the funders support what the politicians request, the religious authorities provide moral cover — no one is accountable when it goes wrong.

What the architecture accomplishes is the monopolisation of power under claimed emergencies that exist only in computer models. These models cannot be realistically examined or challenged by those who will live under the policies they justify. The models are opaque, the assumptions are buried in code and parameters not available to the public, the expertise required to scrutinise them is concentrated in the same institutions that produce them. Dissent becomes functionally impossible when ‘the science’ is embodied in ‘black box’ simulations that only credentialed experts can interpret — and those experts all happen to work for the institutions claiming emergency authority.

This is ethical monism realised through infrastructure, administration, and raw power. Spinoza gave us immanence — ethics inside nature. Carus gave us the scientific anchor — one reality, knowable by method. Bogdanov gave us organisational logic — coordination as the good. Küng and Swidler gave us the Global Ethic declaration. Stephen Rockefeller and Maurice Strong gave us the Earth Charter — the concepts crystallised into institutional framework. Systems theorists (Bertalanffy, Boulding, Churchman) delivered us the methods. Cyberneticians (Leontief, Beer, Ashby) gave us the tools.

And now we see what it means to live inside a world where ethics claims to be derived from nature, nature is defined by models, models are controlled by institutions, and institutions are building the authority to enforce what the models prescribe — with no accountability when the models are wrong, and no mechanism for those affected to verify or contest the emergency.

What emerges is administrative monism with no possibility of appeal: when the same ethical framework is embedded at every scale — from the payment protocol declining your transaction to the Security Council resolution authorising force — there is no institutional layer outside the system to which one can turn, because the ethic has become the infrastructure itself.

Spinoza’s system in its contemporary implementation eliminates free will.

Automated compliance where choice is removed by design, where understanding becomes irrelevant because the architecture decides for you. This is Yuval Noah Harari’s dataism operationalised66: the algorithm knows better than you do, processes more information than you can, and therefore optimised you out of the loop.

Human choice becomes obsolete when the data processing system is superior — or, at least, claims to be.

Because after all, it’s not as though you can realistically appeal, now is it?