Stranded Assets

The formulas that already price your mortgage, your car loan, your business line of credit are being extended to include climate and ecosystem variables.

The question is not whether this will affect you. It is when, and by how much.

Executive Summary

What follows is technical, but the mechanism is straightforward.

In the early 2000s, two fund managers asked a simple question: what happens to fossil-fuel companies if governments actually enforce their climate commitments? Their answer was that reserves currently treated as assets would have to be written off.

They called these ‘stranded assets’, and their thesis reframed climate change as a problem for investors rather than environmentalists.

The argument proved remarkably successful. The Bank for International Settlements now warns that climate-related financial crises could destabilise the entire system. The BIS considers these ‘Green Swan’ crises certain to occur — the only uncertainty is timing.

That certainty deserves scrutiny. The institutions warning of the coming crisis also control the policy levers that would trigger it. Assets become stranded when regulators enforce carbon budgets. The models forecasting instability are produced by the same network that sets the supervisory parameters determining how banks must respond — and the same models feed into the IPCC and IPBES assessments that define the ‘scientific consensus’ justifying the carbon budgets in the first place.

Central bankers call for anticipatory action to prevent the crisis — while simultaneously engineering the conditions under which it occurs.

The outcome is governance by coefficient. Elected parliaments never voted on which assets should be stranded or which industries should survive. Those decisions are being made through risk weights adjusted in Basel, stress-test scenarios produced by the NGFS, and capital formulas that most voters have never heard of.

This essay documents who built this architecture, how the pieces connect, and why the financial infrastructure preceded the treaties it claims to implement.

I. Introduction

In 1845 Moses Hess called circulating money the ‘social blood’ of the economy. Marx pushed it further: if credit is blood, the central bank is the heart, and whoever controls it commands the entire circulatory system. Lenin drew the operational conclusion — a single state bank would provide ‘universal accounting and control’.

Bogdanov through Tektology established the model, while Wassily Leontief created input-output analysis, tracing every flow of goods through every sector, making the vision computable. Flip Leontief from mapping production to mapping dependencies, and the whole economy becomes a system that can be monitored, stress-tested, and controlled.

PPBS implemented at macro in 1961, but what was missing was infrastructure at micro — to make individual transactions conditional on centrally defined criteria. That build-out is now underway through Central Bank Digital Currencies.

The stated rationale is environmental.

II. The Intellectual Trail

In October 2006, the UK Treasury published the Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change1 — commissioned by Gordon Brown (Chancellor), delivered to Tony Blair (Prime Minister).

Led by Nicholas Stern, former Chief Economist of the World Bank2, the 700-page report made a simple argument: the benefits of strong, early action on climate change outweigh the costs of inaction.

It framed climate change not as an environmental problem but as an economic one — and therefore a problem for finance ministries, not just environment ministries.

Stern later became Chair of the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics3 — the same Grantham Institute that would partner with Carbon Tracker4, produce the path-dependence research for the New Climate Economy initiative5, and co-found INSPIRE6 as the NGFS’s research stakeholder7.

The intellectual lineage runs directly from Labour’s UK Treasury to LSE Grantham to the central-banking network.

The disclosure infrastructure was even older. In 2000, Paul Dickinson and Tessa Tennant founded the Carbon Disclosure Project8 (CDP) with a simple premise: investors could use their leverage to encourage companies to disclose environmental information. The first year, 35 investors signed CDP’s request for climate data; 245 companies responded. By 2024, nearly 25,000 organisations disclosed through CDP, backed by over 740 financial institutions with more than $130 trillion in assets9.

CDP’s significance is that it created the norm of voluntary disclosure before regulators made it mandatory. When the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) was launched in 201510, it was not building from scratch — it was formalising and standardising what CDP had pioneered for fifteen years.

CDP’s questionnaires are now fully aligned with TCFD recommendations. The same pipeline that carried the stranded-asset thesis from advocacy to regulation — voluntary norm → regulatory expectation → supervisory requirement — had already been tested on disclosure itself.

III. The Stranded Asset Thesis

In the early 2000s, two fund managers at Henderson Global Investors — Nick Robins and Mark Campanale — developed an argument that would eventually reshape global finance11. Their thesis was simple: if governments ever enforced carbon budgets consistent with stated climate targets, the bulk of fossil-fuel reserves already on corporate balance sheets would become unburnable. Assets treated as valuable today would have to be written off tomorrow.

Climate risk was financial risk.

Decades of moral advocacy had failed to shift capital at scale. Robins and Campanale recast the problem in the language of portfolio management — stranded assets, unbooked liabilities, systemic mispricing.

The term itself was not new. In March 2000, the European Commission published a Green Paper on greenhouse gas emissions trading12. Discussing how new market entrants would fare under a trading regime, the document noted that newcomers ‘will have no costs to bear in respect of ‘stranded assets’ (investments made without the knowledge of subsequent policy instruments)’.

The concept was already present in EU climate-policy vocabulary — eleven years before Carbon Tracker’s first report.

By 2007, the vocabulary had migrated into energy-infrastructure planning. That May, the IEA Greenhouse Gas R&D Programme published a technical study on ‘CO2 Capture Ready Plants’13. The report’s stated rationale: ‘The aim of building plants that are capture ready is to reduce the risk of stranded assets and ‘carbon lock-in.’’

The phrasing linked stranded assets to Gregory Unruh’s ‘carbon lock-in’ concept — an academic framework, published in Energy Policy in 200014, arguing that industrial economies had become locked into fossil-fuel systems through path-dependent co-evolution of technology and institutions.

The IEA report warned that new coal plants built without provisions for carbon capture risked becoming stranded if regulatory or economic drivers later required CO₂ abatement. Four years before Carbon Tracker’s first publication, the stranded-asset concept was already operational guidance in OECD energy-policy circles1516.

What Robins and Campanale did was operationalise it at the level of financial markets.

In 2009, with seed funding from the Rockefeller Brothers Fund17, they founded Carbon Tracker. Their 2011 report, ‘Unburnable Carbon’18, attached the stranded-asset concept to specific reserve data and introduced the term ‘carbon bubble’.

If markets were pricing fossil-fuel reserves as fully extractable, and those reserves could never be burned, then valuations were fundamentally wrong.

The thesis gained traction fast. In 2012, Bill McKibben’s Rolling Stone article — ’Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math’19 — translated Carbon Tracker’s analysis for a mass audience. Divestment campaigns proliferated. By 2014, the Rockefeller Brothers Fund announced it would divest from fossil fuels entirely20.

But to move capital at scale, the thesis had to enter financial regulation.

IV. The Network Emerges

In April 2013, Carbon Tracker partnered with the Grantham Research Institute at the London School of Economics to publish ‘Unburnable Carbon 2013: Wasted Capital and Stranded Assets’21. The report revealed that despite fossil-fuel reserves already exceeding any plausible carbon budget, $674 billion had been spent the previous year developing new potentially stranded assets.

It called on financial regulators to require disclosure of embedded CO₂ emissions and urged finance ministers to incorporate climate change into systemic-risk assessment. By the time of publication, the analysis was already being used by HSBC, Citigroup, and Standard & Poor’s to inform valuation scenarios.

That same month — April 2013 — a separate intellectual project was taking shape. The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate22, chaired by former Mexican president Felipe Calderón, began assembling research for what would become the New Climate Economy initiative23.

In November 2014, the Grantham Research Institute delivered a key contributing paper: ‘Path dependence, innovation and the economics of climate change’24. The paper provided the theoretical foundation for why stranded assets mattered. Economies were locked into dirty-technology trajectories; innovation itself was path-dependent; delay would compound costs.

The authors cited Ben Caldecott’s Oxford Stranded Assets Programme25 and a 2012 World Bank working paper on stranded assets and capital transition.

The economic theory supporting the stranded-asset framework was being built in parallel with the empirical analysis — not iteratively, as science proceeds, but coordinated, as engineering requires.

Meanwhile, the United Nations climate apparatus was not waiting for central bankers to act.

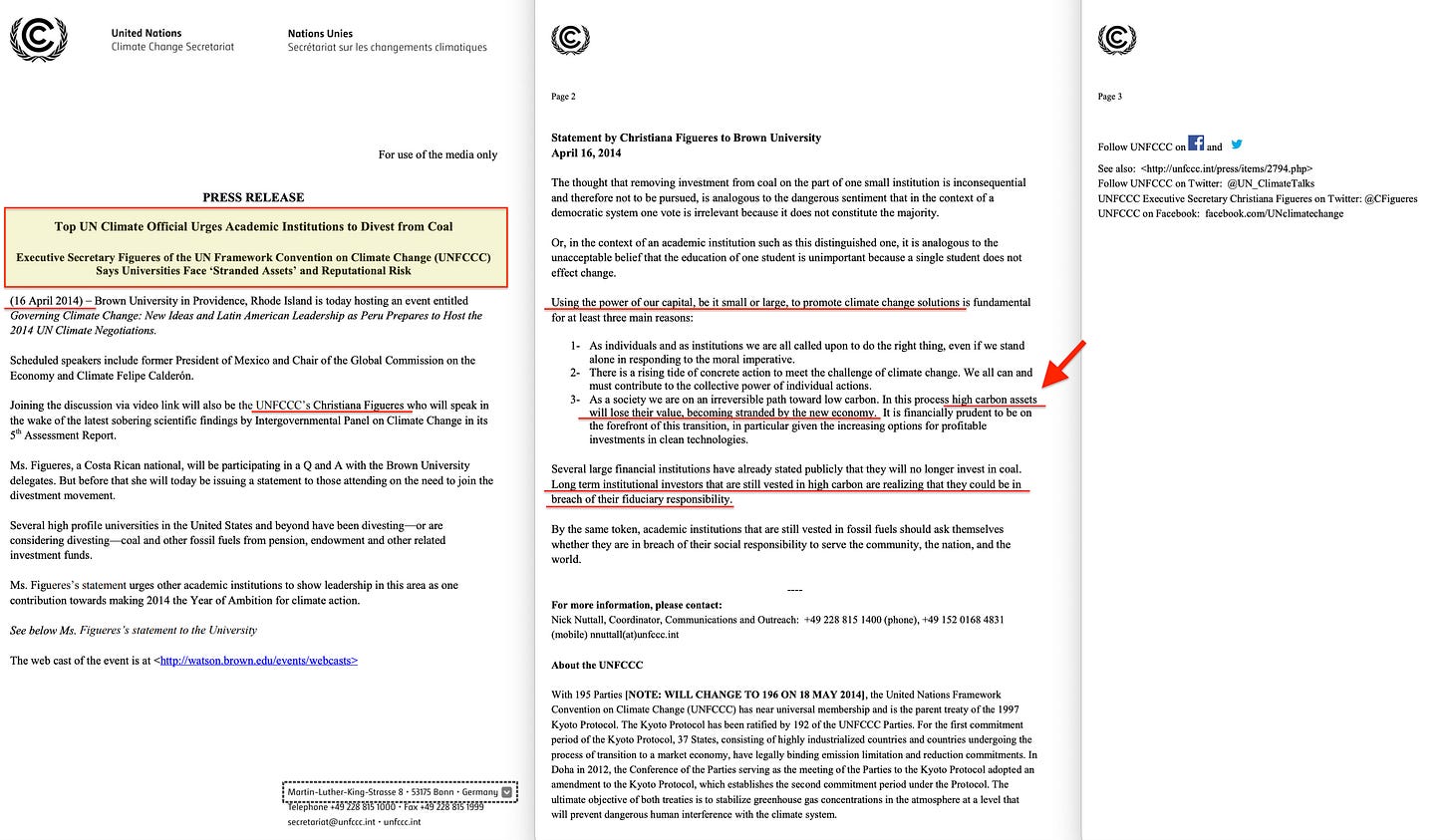

In April 2014 — eighteen months before Bank of England Governor Mark Carney’s celebrated ‘Tragedy of the Horizon’ speech — Christiana Figueres, Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, issued a statement to Brown University urging academic institutions to divest from coal26. The UNFCCC press release carried the headline:

Top UN Climate Official Urges Academic Institutions to Divest from Coal — Executive Secretary Figueres Says Universities Face ‘Stranded Assets’ and Reputational Risk27.

Figueres was explicit:

As a society we are on an irreversible path toward low carbon. In this process high carbon assets will lose their value, becoming stranded by the new economy. It is financially prudent to be on the forefront of this transition… long-term institutional investors that are still vested in high carbon are realizing that they could be in breach of their fiduciary responsibility.

The scheduled speaker at that same Brown University event was Felipe Calderón — chair of the commission for which Grantham was producing the path-dependence research.

V. From Advocacy to Regulation

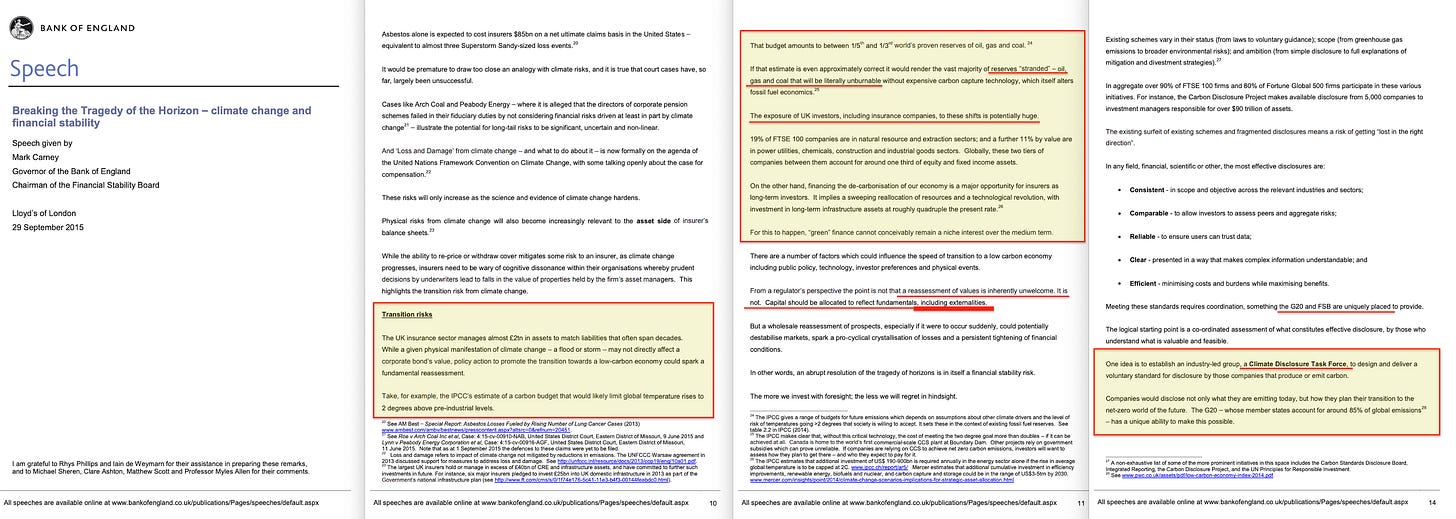

September 2015 brought the pivot from advocacy to regulatory infrastructure. Mark Carney, then Governor of the Bank of England and Chair of the Financial Stability Board, delivered his ‘Tragedy of the Horizon’ speech at Lloyd’s of London28. The title named the problem: climate damages would materialise beyond the typical horizons of central bankers, politicians, and corporate executives.

The solution was to bring future risk into present balance sheets.

Carney warned that meeting a 2°C target would render the remaining fossil-fuel reserves unburnable. He announced the creation of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), to be chaired by Michael Bloomberg29.

Two months later, the coordinated nature of the rollout became visible. At COP21 in Paris — the conference that produced the Paris Agreement — François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France, delivered a speech using identical vocabulary30.

He framed the central question as ‘how to prevent a misallocation of capital to carbon-intensive sectors or stranded assets’. He cited Carney’s ‘tragedy of the horizon’ formulation. He announced that the Financial Stability Board, ‘with the support of the recent G20 in Antalya’, would establish ‘very shortly — by the beginning of 2016 — another dedicated task force’ whose work ‘should be completed within one year in order to rapidly ensure the effective disclosure on climate risk’.

Villeroy’s speech laid out three categories of climate-related financial risk that would become canonical: direct physical risks, liability risks, and:

… macroeconomic risks related to the transition between two production models, which can result in disorderly adjustments in sectors too heavily exposed to global warming or that become unviable.

He observed that:

… the market value of most carbon-intensive industries has already been impacted. And re-pricing may occur rapidly and abruptly’

By the time Carney and Villeroy spoke, Carbon Tracker had already presented to a Financial Stability Board session. The concepts were not new to the audience — they were being given regulatory form.

The TCFD published its recommendations in June 201731, establishing a voluntary but increasingly standard framework for climate-risk disclosure.

In December 2017, French President Emmanuel Macron convened the One Planet Summit in Paris32 — co-hosted by the United Nations and the World Bank — on the second anniversary of the Paris Agreement. The summit’s stated purpose was to accelerate climate finance commitments.

At that summit, eight central banks and supervisors announced the formation of the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS)33. The NGFS was not an independent initiative by cautious technocrats discovering a new risk category; it was launched at a political event designed to align financial flows with treaty commitments.

By January 2026, NGFS membership had grown to 149 institutions34.

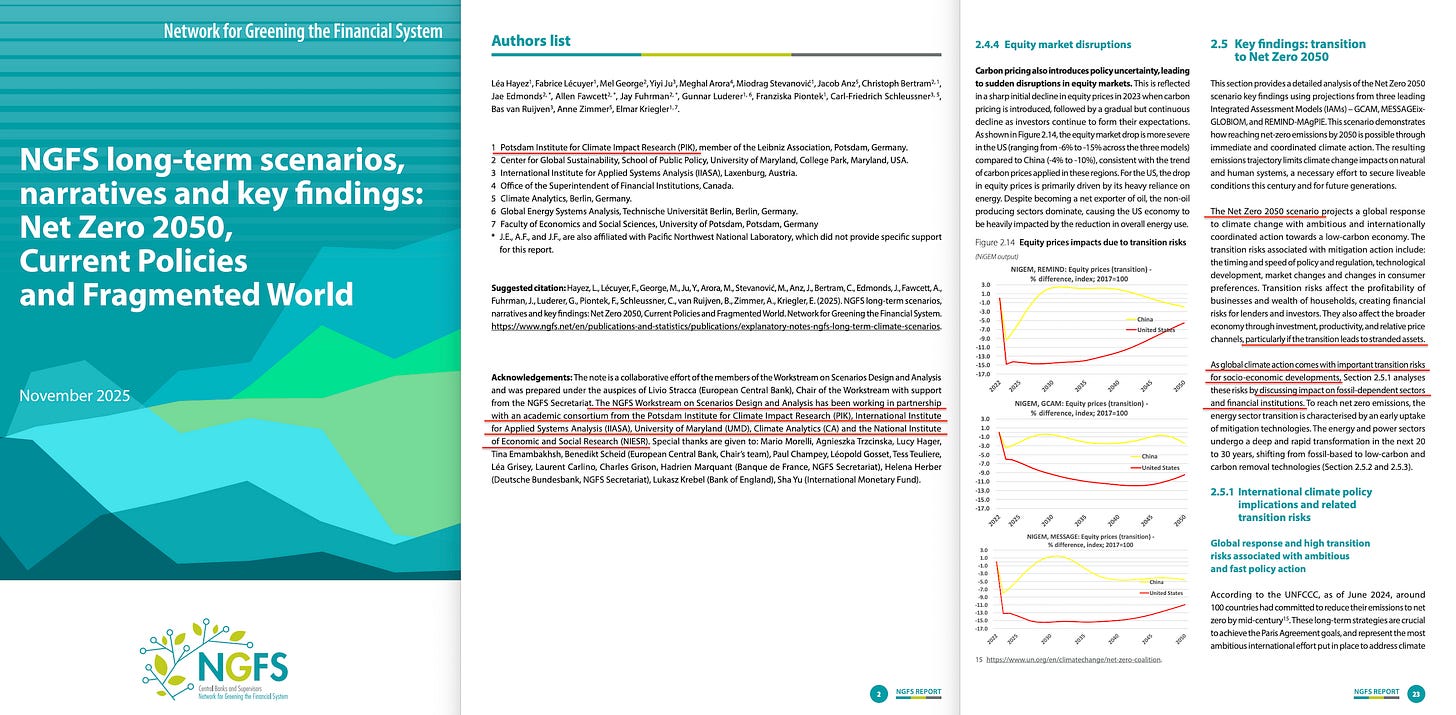

The scenario work underpinning NGFS stress tests was not produced by central banks themselves. It was built by an academic consortium — the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research35, IIASA, the University of Maryland, Climate Analytics, and NIESR — whose funding came from Bloomberg Philanthropies and ClimateWorks Foundation.

ClimateWorks, launched in 2008 with backing from the Hewlett, Packard, and McKnight foundations, has disbursed over $2 billion in grants. Its strategy is explicit: help regulators fold net-zero analysis into supervisory frameworks. In 2019, ClimateWorks partnered with the LSE Grantham Research Institute to create INSPIRE36 — now the NGFS’s designated ‘research stakeholder’.

INSPIRE’s advisory committee is chaired by Nick Robins37.

VI. The Asset Management Pivot

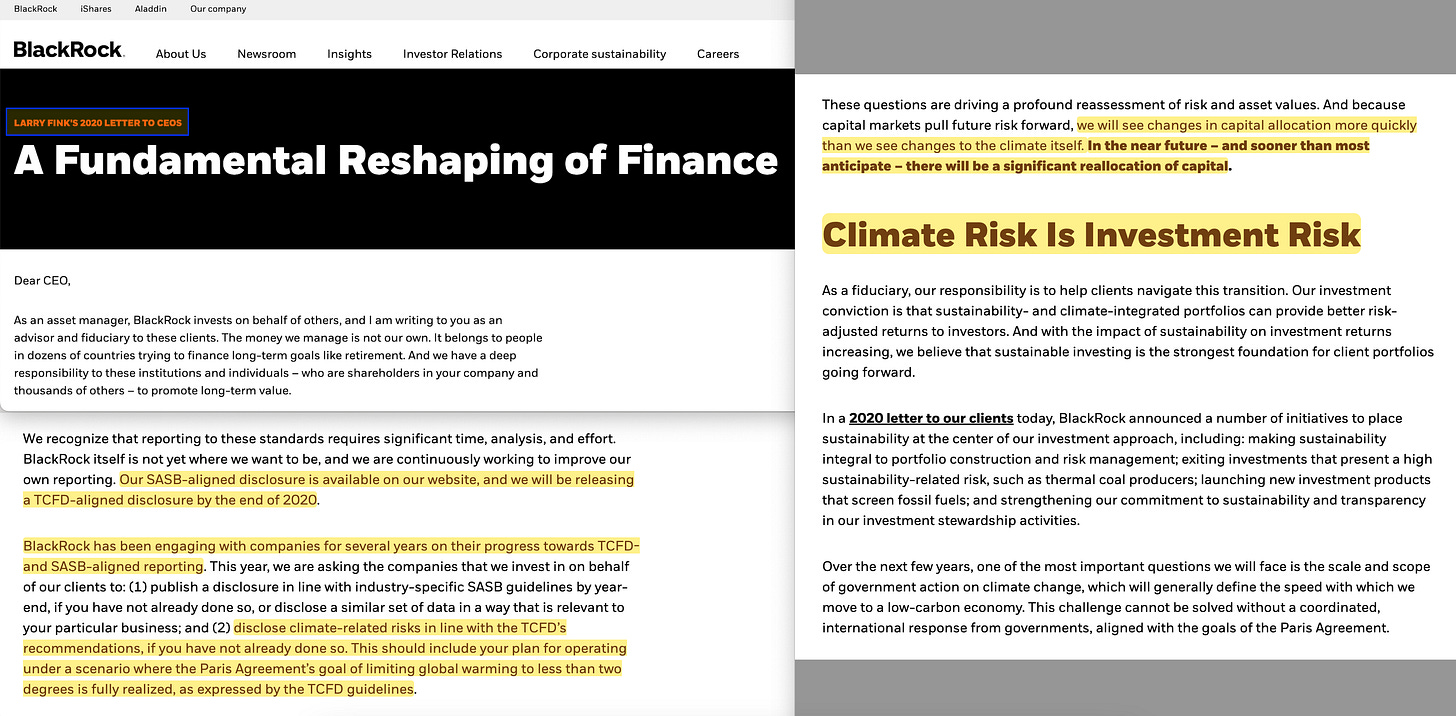

In January 2020, Larry Fink — CEO of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager with roughly $10 trillion under management — published his annual letter to CEOs. The message was blunt: ‘Climate risk is investment risk’38.

The letter announced that BlackRock would exit investments presenting high sustainability-related risk, including thermal coal producers. It called for companies to disclose climate risks in line with TCFD recommendations and to publish SASB-aligned sustainability information. Fink warned that:

… because capital markets pull future risk forward, we will see changes in capital allocation more quickly than we see changes to the climate itself. In the near future — and sooner than most anticipate — there will be a significant reallocation of capital.

When the world’s largest asset manager made TCFD-aligned disclosure a condition of engagement, the stranded-asset framework became a de facto requirement for public companies seeking capital.

That same year, the European Union enacted the Taxonomy Regulation (2020/852), entering into force in July 202039. The regulation created a classification system defining which economic activities qualify as ‘environmentally sustainable’ across six objectives: climate change mitigation, climate change adaptation, sustainable use of water and marine resources, transition to a circular economy, pollution prevention, and protection of biodiversity.

The taxonomy criteria — developed by a Technical Expert Group with representation from the same network — determine which investments can be marketed as ‘green’ in Europe. Activities that fail to meet taxonomy criteria face disclosure requirements that translate into higher cost of capital.

The stranded-asset thesis had become European law. Not as a prohibition, but as a classification — a system that sorts economic activities into taxonomies and attaches differential capital costs to each category.

But the regulation was never limited to environmental criteria. Recital 6 states:

Further guidance on activities that contribute to other sustainability objectives, including social objectives, might be developed at a later stage.

The infrastructure was designed from the start to extend to any criteria the operators choose to add.

Climate was merely the pilot.

In April 2021, Mark Carney — now UN Special Envoy for Climate Action and Finance40 — launched the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ)41 alongside the UNFCCC COP26 presidency. GFANZ was designed as an umbrella coalition, uniting the Net-Zero Banking Alliance, Net-Zero Asset Managers Initiative42, Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance43, and Net-Zero Insurance Alliance44 under one strategic forum. By November 2021, more than 450 firms representing $130 trillion in assets had joined.

GFANZ reports periodically to the Financial Stability Board45 — the same FSB that Carney had chaired when he launched TCFD. The architecture is circular: the regulatory body that created the disclosure framework receives reports from the private-sector coalition implementing it, co-chaired by the same person who launched the regulatory initiative.

In June 2022, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision46 — the body that writes the global standards for bank capital regulation — published ‘Principles for the effective management and supervision of climate-related financial risks’47. The document’s eighteen principles covered corporate governance, internal controls, risk assessment, and management reporting.

Principle 6 stated that banks should ‘identify, monitor and manage all climate-related financial risks that could materially impair their financial condition’. Principle 12 required that climate risk be incorporated into credit risk assessment, capital planning, and stress testing.

The Basel Committee’s publication was framed as principles-based guidance, not binding rules. But the committee ‘expects implementation of the principles as soon as possible’ and announced it would ‘monitor progress across member jurisdictions’.

The progression was visible: voluntary guidance → supervisory expectation → monitored implementation → eventual integration into capital requirements.

VII. The Green Swan

In January 2020, the Bank for International Settlements and the Banque de France published The Green Swan: Central Banking and Financial Stability in the Age of Climate Change48. The book marked the moment when the stranded-asset thesis became official BIS doctrine.

The report’s opening pages read like a jurisdictional claim. ‘Climate change therefore falls under the remit of central banks, regulators and supervisors, who are responsible for monitoring and maintaining financial stability’. The authors called for an abandonment of traditional backward-looking risk models in favour of forward-looking scenario analysis. Traditional models ‘merely extrapolate historical trends’; climate requires something new.

The report warned that climate-related risks could trigger ‘green swan’ events — systemic financial crises analogous to black swans but with a crucial difference: their eventual occurrence was not merely possible but certain. The question was timing and form, not probability.

Black swans are unpredictable precisely because no one controls the conditions that produce them. Green swans are ‘certain’ because the institutions issuing the warning also control the policy levers that would trigger the event. Assets become stranded when regulators enforce carbon budgets.

The ‘certainty’ is not a climate forecast; it is a statement of policy intent.

The report itself acknowledges the impossibility of prediction:

… integrating climate-related risk analysis into financial stability monitoring is particularly challenging because of the radical uncertainty associated with a physical, social and economic phenomenon that is constantly changing and involves complex dynamics and chain reactions.

Radical uncertainty — yet certain outcomes. The only way both statements can be true is if the certainty derives not from climate science but from the policy response the authors themselves are designing.

The stranded-asset mechanism was central to their analysis. The report warned that if fossil-fuel reserves were to become unburnable due to a rapid low-carbon transition, the result could be an ‘archetypal fire sale’ as stranded assets suddenly lost value — ‘potentially triggering a financial crisis’. In the worst case, ‘green swan events may force central banks to intervene as ‘climate rescuers of last resort’ and buy large sets of devalued assets, to save the financial system’.

The report named this possibility a ‘climate Minsky moment’ — a systemic crisis triggered by an abrupt change of sentiment regarding the ability to repay climate liabilities.

The same institutions that define the carbon budgets, embed them in supervisory frameworks, and thereby create the stranding conditions also position themselves as the buyer when the fire sale arrives.

The ‘rescue’ is the transfer mechanism. Assets move from private balance sheets to central bank balance sheets under the banner of financial stability. The crisis is not a risk to be avoided; it is the event that consolidates the architecture.

But the Green Swan did more than translate Carbon Tracker’s thesis into central-bank vocabulary. It assigned central banks a coordinating role that extended well beyond traditional mandates. ‘Central banks must also be more proactive in calling for broader and coordinated change’.

The report called for ‘exploring new policy mixes’ combining fiscal, monetary, and prudential tools. In 2023, the Fabian Society’s ‘In Tandem’ report provided the operational blueprint, detailing how Treasury and Bank of England should coordinate on precisely such an expanded mandate. The principle stated in 2020 was being institutionalised by 2023.

The report also called for ‘considering climate stability as a global public good’, for ‘integrating sustainability into accounting frameworks at the corporate and national level’, and for reforms of the international monetary and financial system Jean-Claude Trichet had outlined a decade earlier49.

The scope was explicit:

Financial and climate stability could be considered as two interconnected public goods, and this consideration can be extended to other human-caused environmental degradation such as the loss of biodiversity.

Much like in the case with the EU Taxonomy, climate was merely the entry point. The framework was designed to absorb whatever came next.

The Green Swan acknowledged the limits of central bank action. It cautioned that ‘relying too much on central banks would be misguided’ and that central banks ‘cannot (and should not) simply replace governments and private actors’. But the operational implication was clear: if governments failed to act, central banks would face pressure to expand their interventions — or accept responsibility for financial instability they had identified but failed to prevent.

The Green Swan is the closest thing to an outright confession the architecture has produced. It was published in January 2020 — immediately prior to COVID, before the discourse around it became politically contentious — when the authors presumably thought no one outside the central banking community was paying attention.

VIII. The UNFCCC as Distribution Channel

The UNFCCC did not wait for central banks to finish their work before amplifying the stranded-assets framework.

In August 2015, France submitted its National Low-Carbon Strategy to the UNFCCC50. The document called on policymakers to ‘raise awareness among investors about the fact that certain assets are susceptible to depreciation, and should not be prioritised in an investment portfolio’. It urged ‘operational consideration of ‘carbon risk’’. The stranded-asset thesis was embedded in official national policy before the Paris Agreement was even signed51.

In September 2016, the UNFCCC’s newsroom promoted a Carbon Tracker report directly52, headlining research that concluded renewable energy was now cheaper than fossil fuels and that ‘planning for business-as-usual load factors and lifetimes for new coal and gas plants is a recipe for stranded assets’.

In January 2018, the UNFCCC promoted a Potsdam Institute study53 finding that ‘implementation of the Paris Agreement and related climate policies will lead to divestment from coal and other fossil fuels’ — with investors divesting from coal ‘ten years prior to the implementation of climate policies, realizing that future policies will shorten the profitability of coal power plants’.

In June 2019, the UNFCCC promoted a CDP report warning of potential $250 billion in stranded-asset losses, structured around TCFD recommendations54.

In 2019, the UN University Institute for Natural Resources in Africa published a 42-page report titled ‘Africa’s Development in the Age of Stranded Assets’55, citing Carbon Tracker and Grantham directly.

In 2021, the UNFCCC’s Climate Action Pathway56 embedded stranded assets as operational guidance for policymakers, banks, and investors — recommending that financial institutions ‘evaluate alignment with net zero emissions by 2040s and corresponding risks of stranded assets’ and ‘exclude from mandates investment linked to new exploration of oil/gas/coal... to minimize risk of new stranded assets’.

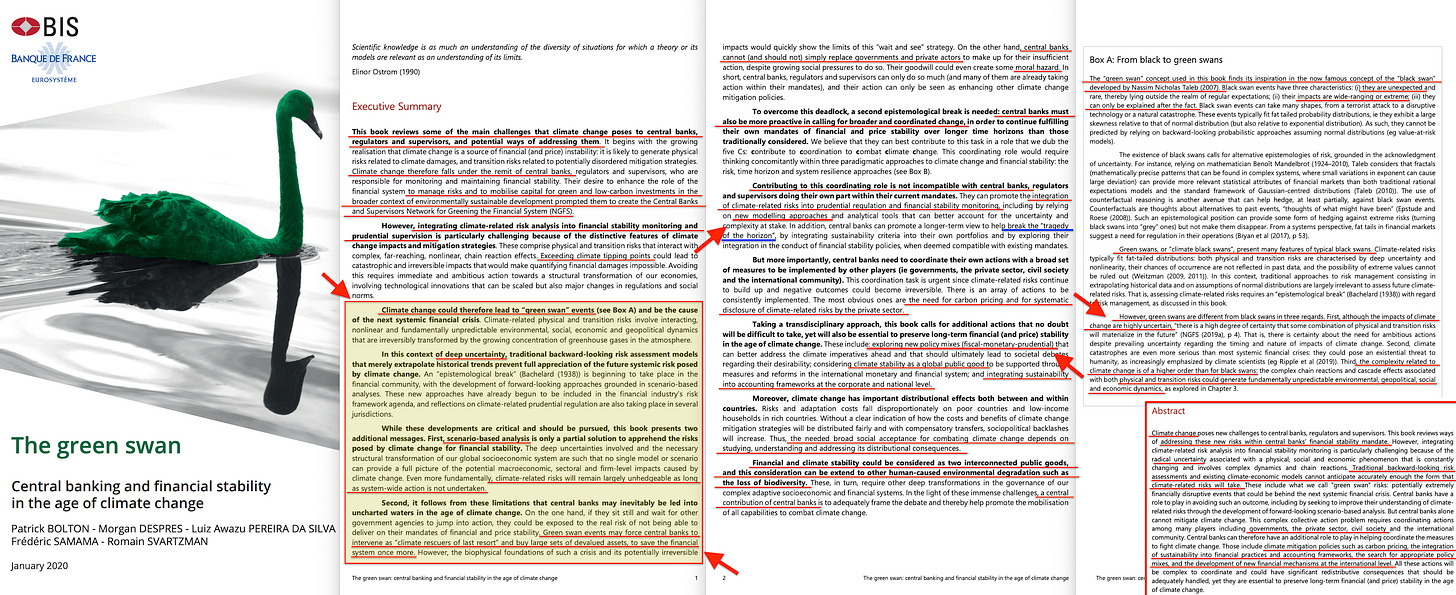

In 2023, the Foreword to the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report57 — signed by the heads of the World Meteorological Organization and UN Environment Programme — cited stranded assets as a risk of delayed climate action.

A thesis coined by two fund managers had become the canonical vocabulary of global climate governance — eighteen months before the Paris Agreement was even signed.

The financial architecture preceded the treaty, exactly as the GEF — first proposed by France in 198958 — preceded the UNFCCC and CBD. France hosted COP21 where the Paris Agreement was signed59, then the One Planet Summit where NGFS launched60.

The Banque de France co-published the Green Swan.

IX. Personnel

Nick Robins never held elected office. He never sat on a central bank board. But he appears at nearly every node where ideas become ‘best practice’.

He coined the stranded-asset concept with Campanale at Henderson Global Investors. He moved to HSBC, where he founded the bank’s Climate Change Centre of Excellence (2007–2014). He joined the UN Environment Programme’s Inquiry into the Design of a Sustainable Financial System61 (2014–2018). In 2018, he joined the LSE Grantham Research Institute62, where he co-founded INSPIRE and co-chaired the NGFS-INSPIRE study group on biodiversity and financial stability. He advises the UK government on green finance. He sits on the board of Carbon Tracker. He co-founded Planet Tracker, which extends the stranded-asset methodology to natural capital.

The structure is a feedback loop: Grantham and INSPIRE package research; NGFS circulates it as guidance; supervisors convert guidance to expectations; expectations harden into requirements. Robins sits at the centre, connecting think tanks, academic institutes, UN bodies, and regulatory networks.

Mark Carney’s trajectory is different — visible, credentialed, and ultimately political. After thirteen years at Goldman Sachs, he became Governor of the Bank of Canada63 (2008–2013), then Governor of the Bank of England64 (2013–2020) — the first non-Briton to hold the position. He simultaneously chaired the Financial Stability Board 65(2011–2018), where he launched TCFD; served as First Vice-Chair of the European Systemic Risk Board66 (2013–2020); and chaired the Global Economy Meeting of the Bank for International Settlements67 (2018–2020).

In December 2019, as his Bank of England term ended, Carney was appointed UN Special Envoy for Climate Action and Finance68. In April 2021, he launched GFANZ69. Simultaneously, he became Vice Chair of Brookfield Asset Management, where he heads transition investing for a $15 billion Global Transition Fund that finances wind farms, green hydrogen, and grid upgrades. He joined the boards of Stripe70, Bloomberg Philanthropies, and the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

In March 2025, Carney became Prime Minister of Canada71.

One person spans Goldman Sachs → Bank of Canada → Bank of England → FSB → BIS → UN → private asset management → political office.

At each node, he advanced the same framework: climate risk is financial risk; financial risk requires disclosure; disclosure enables pricing; pricing allocates capital. The framework is now embedded in the supervisory infrastructure of every major jurisdiction — including the one he now governs.

X. From Climate to Nature

In April 2021, the NGFS and INSPIRE launched a joint Study Group on Biodiversity and Financial Stability, co-chaired by Ma Jun of the People’s Bank of China and Nick Robins72. In 2022, the group published ‘Central banking and supervision in the biosphere’73. The mechanics are familiar: swap CO₂ budgets for ecosystem-service dependencies — water, pollination, flood protection, soil quality — using databases like ENCORE and EXIOBASE374.

The report also names the enforcement layer:

… environmental crime, and how biodiversity risks are transmitted through international financial flows and trade. Central banks and supervisors need to consider their role in addressing these factors.

The same FATF machinery built for terrorist financing — updated in 2021 to cover environmental crimes — now extends to biodiversity.

The organisational node carrying the methodology across domains is Planet Tracker75 — co-founded by Mark Campanale and Nick Robins. Carbon Tracker translated carbon limits into stranded assets. Planet Tracker does the same for fisheries, plastics, water, land use. The analytical machinery built for climate is being extended to the entire biosphere.

In December 2025, the European Central Bank published Occasional Paper 380: ‘Nature at risk’76. The paper introduces Nature Value-at-Risk — a methodology for converting ecosystem conditions into portfolio-denominated risk metrics. Finding: roughly 72% of euro-area non-financial corporations are highly dependent on at least one ecosystem service; 75% of corporate bank lending flows to these firms.

The paper calls for mapping Nature Value-at-Risk into standard credit-risk parameters: probability of default, loss given default, exposure at default. If supervisors adopt the framework, ecosystem conditions will feed into capital requirements, which will feed into lending costs across the economy.

The mathematics underneath is Leontief — inverted. Where the original input-output tables asked ‘how much steel does a car factory need?’, the ECB’s model asks ‘how much does this sector’s output depend on pollination, or flood protection, or water purification?’ The entire economy becomes a matrix of ecosystem dependencies. Degradation anywhere propagates through the system as quantified risk.

This was predictable. The ECB paper was published around the same time I speculated about inverting Leontief. Once you understand the destination, the route becomes easier to decipher.

XI. Stranded Assets as Modeled Parameter

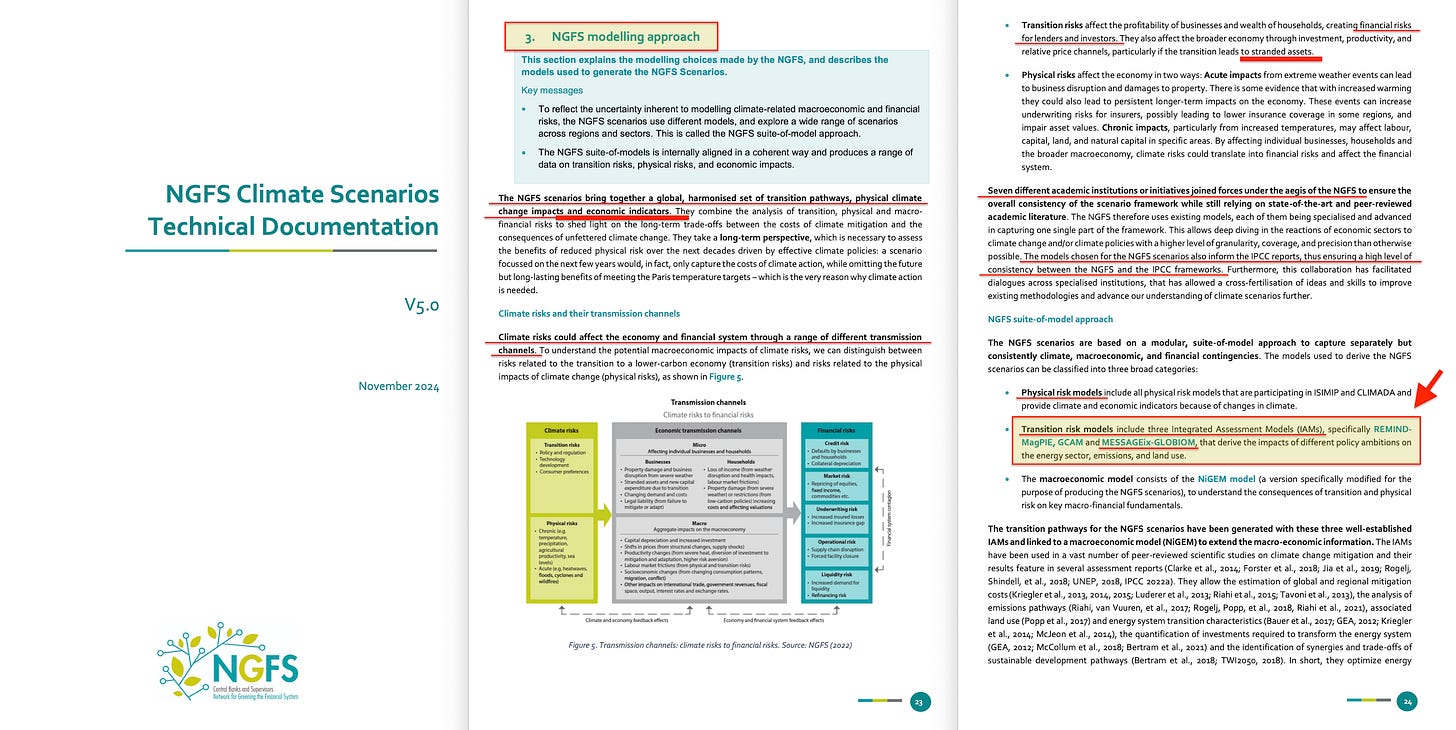

By November 2025, stranded assets had moved from thesis to calibrated variable. The NGFS’s fifth vintage of long-term climate scenarios77 — produced by the same Potsdam-IIASA-Maryland-Climate Analytics consortium — explicitly models stranded assets as a transmission channel through which transition risks affect the macroeconomy and financial system.

The November 2025 NGFS scenarios document states that global climate action ‘comes with important transition risks for socio-economic developments’ and dedicates analysis to ‘discussing impact on fossil-dependent sectors and financial institutions’ — ‘particularly if the transition leads to stranded assets’. The coal sector’s transformation into a stranded asset is modeled as a specific financial risk.

The short-term scenario framework, published in May 2025, includes ‘financial turmoil due to stranded assets’ as one of the named disorderly-transition pathways central banks use for stress testing78.

When central banks run supervisory stress tests, they are modeling stranded-asset fire sales as a quantified transmission mechanism — complete with sector-level default probabilities and GDP impact estimates.

The thesis Robins and Campanale articulated in the early 2000s is now a parameter in the models that determine capital requirements.

XII. The Mathematics of Control

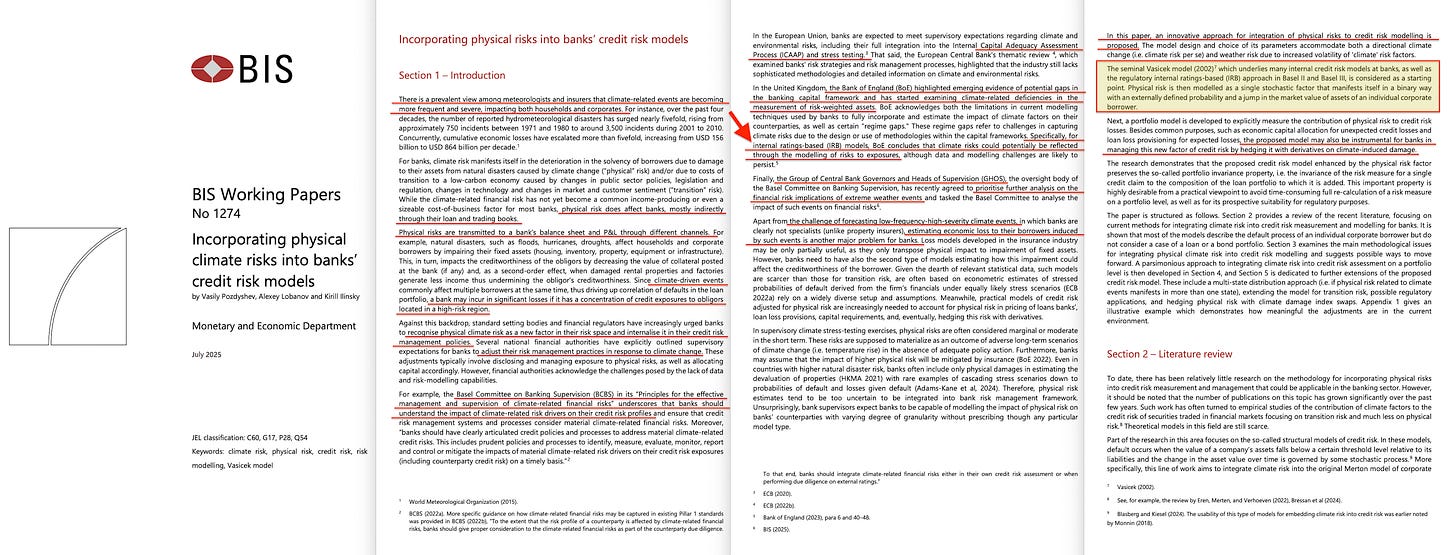

In July 2025, the BIS published Working Paper 1274: ‘Incorporating physical climate risks into banks’ credit risk models’79. The paper provides what had been missing: the mathematical machinery for embedding climate risk into the core formulas that determine bank capital requirements.

The Vasicek model underlies the Basel Internal Ratings-Based (IRB) approach — the framework that translates credit risk into required capital. Working Paper 1274 extends this model to include physical climate risk as an additional systematic factor, alongside the traditional market-risk factor. The extension preserves the ‘portfolio invariance’ property that makes the IRB approach computationally tractable: capital requirements for individual loans can be calculated without reference to the full portfolio.

The timing is revealing. This methodology is being developed for internal models at the exact moment Basel 3.1 is eliminating internal models in favour of standardised risk weights controlled from Basel.

Under Basel 3.1, banks must use a lookup table maintained by the Basel Committee — commercial real estate carries one risk weight, corporate bonds rated BBB carry another.

Regulators already know exactly what sits on each bank’s balance sheet through granular reporting requirements and stress test submissions. The research provides the justification; the standardised approach provides the enforcement. Climate parameters developed through working papers will be hardcoded into the lookup table that all banks must use.

The power to define what counts as risky is the power to decide which assets are viable to hold — and therefore which institutions are even allowed to exist.

The mechanics are technical but the implications are not. The paper models physical risk as a ‘jump’ in asset value — a sudden loss triggered by climate events — with probability q (supplied by meteorological models) and magnitude α (derived from damage functions). These parameters feed into adjusted calculations for probability of default and loss given default. The output is a climate-adjusted risk-weighted asset (RWA) figure.

The paper’s illustrative example is concrete: for a BBB-rated company with commercial real estate in Mobile, Alabama, incorporating hurricane risk at the 95% confidence level increases risk-weighted assets by approximately 20%. This is not a scenario exercise. It is a demonstration of how climate conditions convert into capital costs — and therefore into the price and availability of credit for a business that has done nothing except occupy a particular geography.

The same mechanism that makes one bank’s commercial property exposure suddenly untenable can make another bank’s fossil-fuel exposure suddenly unviable. No public intervention, no headline, no parliamentary debate. Just a technical recalibration in Basel.

The paper also discusses hedging: a proposed ‘climate damage index swap’ that would allow banks to offload physical risk, with the swap spread explicitly appearing in the capital formula. If such instruments develop, climate risk becomes not just measurable but tradeable — a new asset class derived from the stranded-asset framework.

The Vasicek model is the mathematical foundation of bank capital regulation worldwide. Extending it to include climate risk means that ecosystem conditions can, in principle, flow through the same channels that currently transmit credit risk into lending decisions.

In short, a small business in a flood zone will see its interest rates skyrocket, not because its financials are weak, but because an Austrian computer model changed its geography risk weight.

XIII. The Supervisory Turn

Adoption is now underway.

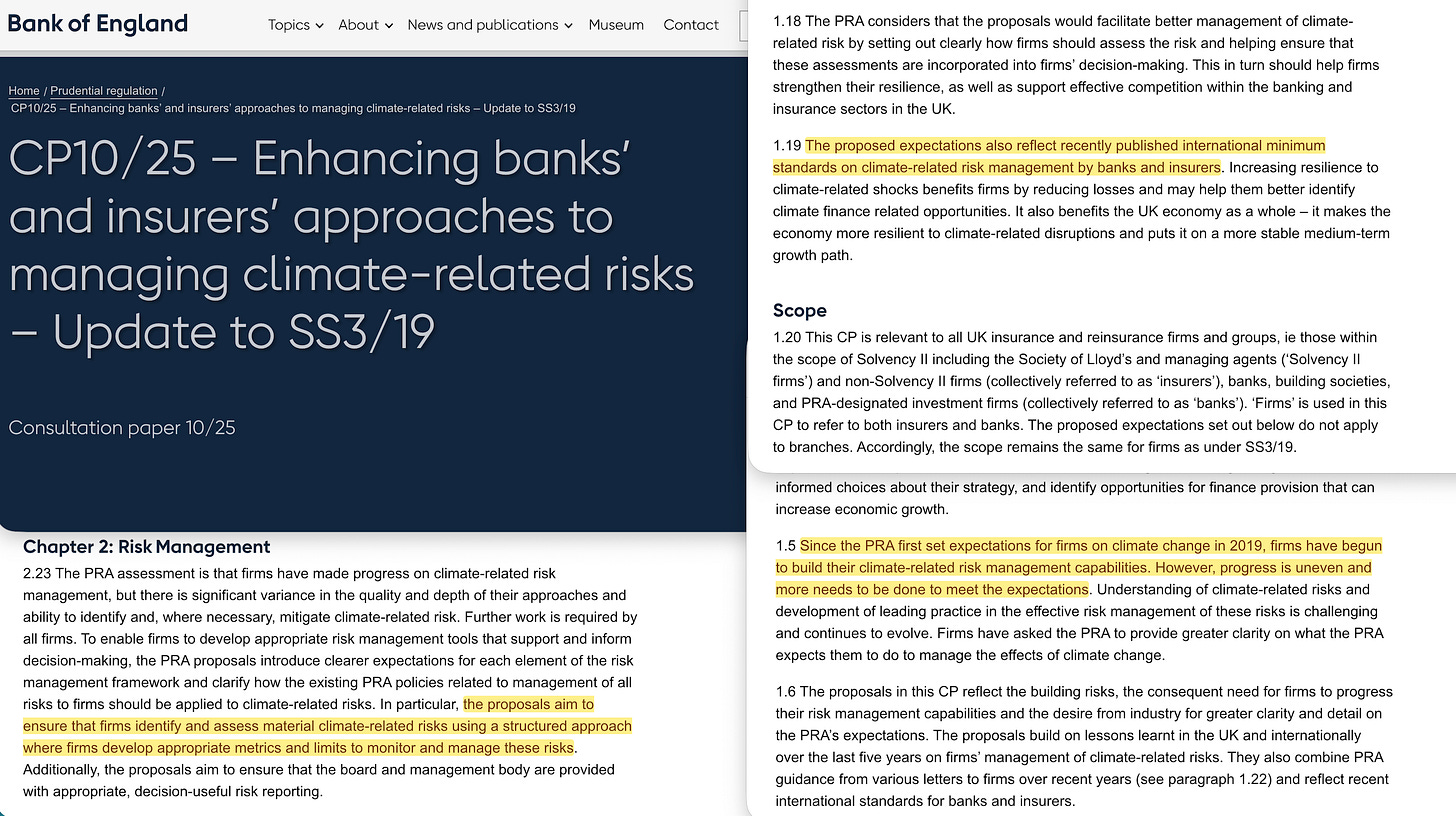

In April 2025, the Bank of England’s Prudential Regulation Authority published Consultation Paper 10/25: ‘Enhancing banks’ and insurers’ approaches to managing climate-related risks’80. The document proposed to update the supervisory expectations first issued in 2019, converting them from high-level principles into detailed, examination-ready requirements.

The consultation paper is explicit about the progression:

Since the PRA first set expectations for firms on climate change in 2019, firms have begun to build their climate-related risk management capabilities. However, progress is uneven and more needs to be done to meet the expectations.

The proposals ‘reflect recently published international minimum standards’ — the Basel Committee’s 2022 Principles — and aim to ensure that firms ‘identify and assess material climate-related risks using a structured approach’ with ‘appropriate metrics and limits to monitor and manage these risks’.

The transmission mechanisms are spelled out. For banks: climate risk must be integrated into Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process (ICAAP)81, Internal Liquidity Adequacy Assessment Process (ILAAP)82, credit risk frameworks, and market risk management. Climate scenario analysis must inform capital adequacy assessments. For insurers: climate risk must be incorporated into the Own Risk and Solvency Assessment (ORSA)83 and reflected in solvency capital requirements across underwriting, reserving, market, credit, and operational risk categories.

The PRA frames this as risk management, not climate policy: ‘Climate-related risks arise through two primary channels—physical risks and transition risks’. But the operational detail reveals the scope. The consultation document warns that:

… transition risks can arise from the adjustment towards a low-emission economy. This could prompt a reassessment of the value of a large range of assets for banks, other lenders and insurers as costs and opportunities from the transition become apparent.

The document acknowledges the stranded-asset mechanism directly:

Transition risk similarly can affect banks through their lending and investment portfolios. A high-emission manufacturer might suffer a loss of business or increased cost from climate-related regulation, reducing its ability to repay a loan (credit risk). Likewise, a utility heavily invested into coal might face a cost of refitting its plants or transitioning into another generation medium, reducing its share price (market risk).

This is now supervisory expectation — the layer where guidance becomes capital requirement through examination.

The Bank of England that Mark Carney led from 2013 to 2020 is now proposing to embed his framework into the supervisory infrastructure that determines which loans get made and at what price.

XIV. The Completion

In November 2025, the OECD published compilation guidance for the 2025 System of National Accounts84 — the international statistical standard for measuring GDP. The update treats depletion of natural resources as a cost of production. Under the 2008 SNA, resource depletion was recorded as an accounting adjustment85. Under the 2025 SNA, it reduces Net Domestic Product, Net National Income, and Net Savings86. The change, the OECD noted, is ‘important to provide better signals to policy makers whether current levels of economic growth are sustainable’.

The infrastructure now extends from financial regulation to national accounting. The scenario work underpinning NGFS stress tests was built by an academic consortium including IIASA, the Potsdam Institute, the University of Maryland, Climate Analytics, ETH Zurich, and the National Institute of Economic and Social Research — funded by grants from Bloomberg Philanthropies and ClimateWorks Foundation.

The NGFS scenarios explicitly list ‘stranded assets’ as a transmission channel through which transition risks affect the economy87. The NGFS technical documentation is explicit:

The models chosen for the NGFS scenarios also inform the IPCC reports, thus ensuring a high level of consistency between the NGFS and the IPCC frameworks.

The transition risk models include IIASA’s MESSAGEix-GLOBIOM — the same integrated assessment model that feeds IPBES biodiversity assessments and CBD treaty frameworks. One model, multiple outputs.

The politician reads the IPCC report; the central banker reads the NGFS scenario; the biodiversity specialist reads the IPBES assessment. Each appears to validate the others.

They are the same model runs, reformatted for different audiences.

By 2017, the same IIASA and Potsdam researchers were publishing in Science. Their paper, ‘A roadmap for rapid decarbonization’88, called for ‘an immediate moratorium on investment in new unabated coal-based energy’ to ‘minimize future stranded assets’. It proposed a ‘carbon law’ of halving emissions every decade. It urged that ‘climate stabilization must be placed on par with economic development, human rights, democracy, and peace’ and that ‘the design and implementation of the carbon roadmap should therefore take center stage at the UN Security Council’.

The authors who build the models also write the policy prescriptions.

In December 2025, the OECD published guidance on ‘Future-Proofing Real Estate Investment’89, applying NGFS scenarios and stranded-asset analysis to a sector worth USD 111 trillion in OECD countries — nearly double total GDP. The vocabulary developed by two fund managers now structures how regulators assess risk across the built environment.

The OECD guidance does not operate in isolation. The Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change has developed ARESI90 — a framework for assessing real estate against sustainability indicators — translating the same NGFS scenarios into portfolio-level screening criteria.

Regulatory guidance from above; investor coalition pressure from below.

The property owner gets caught in between.

XV. The Execution Layer

The Bank for International Settlements is building the infrastructure that could make all of this enforceable at the level of individual transactions.

In its 2023 Annual Economic Report, the BIS outlined the concept of a ‘Unified Ledger’91 — a new type of financial market infrastructure bringing central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), tokenised commercial bank deposits, and other financial claims onto a single programmable platform. The report describes how such a ledger would enable ‘atomic settlement’ — simultaneous exchange of assets where ‘the transfer of one occurs only upon transfer of the other’.

The key capability is programmability. As BIS General Manager Agustín Carstens explained in a November 2023 address92:

A smart contract is a computer program that executes conditional ‘if/then’ and ‘while’ commands. Composability means that many smart contracts, covering a huge variety of transactions and situations, can be bundled together, like ‘money lego.’ With these new functionalities, any sequence of transactions in programmable money and digital assets could be automated and seamlessly integrated.

The BIS blueprint specifies that payments on a unified ledger could be made ‘conditional on some real-world contingency’ — and that such contingency information ‘would also be included’ in the execution environment. Settlement becomes programmable: transactions complete only if conditions are satisfied.

The BIS Innovation Hub93 is not merely theorising. Projects Helvetia94, Jura95, and Mariana96 have tested cross-border settlement of tokenised assets in wholesale CBDC. The Regulated Liability Network proof-of-concept97, developed with the New York Innovation Centre, explored how tokenised central bank money and commercial bank deposits from multiple jurisdictions could operate on shared infrastructure. Carstens has indicated the BIS hopes to extend this work to include tokenised securities.

This is the Hess-Marx-Lenin-Bogdanov-Leontief vision, finally implemented.

The ‘social blood’ becomes executable code. The accounting is no longer retrospective but prospective. Transactions can be validated against whatever criteria operators load into the system.

In his 1858 Fragment on Machines98, Marx described how the ‘general intellect’ — society’s accumulated knowledge — would become embedded in fixed capital, in the machine system itself. The fragment is now realised across two layers: artificial intelligence absorbs the general intellect — the sum of human textual output, reasoning patterns, behavioral data — and processes it into scenarios and parameters; the Unified Ledger enforces those parameters at settlement.

The dictatorship of the proletariat was always supposed to be transitional — the state would ‘wither away’ once control was embedded in social relations.

It finally withers… into technological infrastructure.

The current criteria are framed as sustainability and planetary stewardship. But the infrastructure is indifferent to content. Once built, it will enforce whatever rules it is given. Governance shifts from punishment after the fact to prevention before execution. Violations do not result in fines — they result in failed settlement. The transaction never happens.

This is ‘inclusive capitalism’ — the term favored by the Vatican’s Council and Lynn Forester de Rothschild’s coalition of Guardians. Inclusion sounds generous until you notice it is conditional. You are included if you comply. The conditions are set by coefficients derived from models.

The models are produced by institutions accountable to no electorate.

Fail the criteria and you are not punished, not imprisoned, not explicitly excluded. You just cannot engage in economic transactions.

The legal infrastructure is already in place.

Post-2008 resolution frameworks give authorities power to write down claims and convert deposits to equity over a weekend, without court orders. The 1994 revision of UCC Article 8 replaced ownership of specific securities with ‘security entitlements’ — contractual claims against intermediaries in pooled structures where derivatives counterparties have priority. The 2017 UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Transferable Records, now being adopted globally, makes ownership of digital assets depend on system-recognised control: lose control, lose ownership.

The same BIS that is building the Unified Ledger coordinates the legal harmonisation through which possession is being replaced by control — and control can be reassigned at settlement speed, with no possibility of appeal.

XVI. Closing the Exits

The architecture is not complete without closing alternative rails.

In December 2022, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision finalised its ‘Prudential treatment of cryptoasset exposures’ (SCO60)99, with implementation beginning January 2025. The framework assigns unbacked cryptoassets — Bitcoin, Ethereum, most tokens — a 1250% risk weight.

Banks must hold capital equal to the full exposure value. A bank holding $100 million in Bitcoin must hold $100 million in capital against it.

This is not regulation through prohibition, but prohibition through capital cost. At a 1250% risk weight, the economics of holding unbacked cryptoassets become impossible at institutional scale.

The same Basel framework that is being extended to incorporate climate risk weights simultaneously forecloses the exit to alternative settlement rails.

The architecture thus operates on three axes simultaneously:

Make ‘brown’ assets expensive to hold through elevated risk weights and disclosure requirements

Make ‘green’ assets cheap to hold through favorable taxonomy treatment and reduced capital charges

Close the exit door to alternative rails that might allow capital to escape the classification system entirely

Capital does not merely flow only toward approved activities — it becomes trapped in the system where these rules apply.

XVII. The Explicit Statement

The architects were not subtle about the design.

In April 2019, Sarah Breeden — then Executive Director of International Banks Supervision at the Bank of England — announced that the UK had become ‘the first regulator in the world to publish supervisory expectations’ on climate risk100. Her speech at the Official Monetary & Financial Institutions Forum cited stranded-asset losses of ‘$1tn–$4tn when considering fossil fuels alone, or up to $20tn when looking at a broader range of sectors’. She warned of ‘a climate Minsky moment, where asset prices adjust quickly with negative feedback loops to growth’101.

The operational logic was explicit: scenario analysis ‘should incentivise financial firms to seek to pull forward the transition so that they are ahead of and in control of it — directing their capital to those that are resilient and avoiding those that are not’.

Eight months later, at COP25 in Madrid, Mark Carney stated the design principle in the clearest possible terms102:

Firms that align their business models with the transition to net zero will be rewarded handsomely. Those that fail to adapt will cease to exist.

He described the Bank of England’s forthcoming stress test as revealing ‘the banks — and by extension companies — that are preparing for the transition to net zero as well as those who have not yet developed strategies’. The test would model ‘the late policy action — or climate Minsky moment — scenario that could bring a sudden recognition of the scale of stranded assets’.

And he named the mechanism:

As countries build their policy track records and their credibility grows, the financial system will amplify the impact of those policies and pull forward adjustment to the net zero carbon future.

The financial system as amplifier. Adjustment pulled forward.

Firms that fail to adapt cease to exist.

XVIII. Why Central Banks

This can only be the central banks. No other institution occupies the junction.

The Financial Stability Board sets international standards for financial stability.

The Basel Committee writes the capital formulas — the risk weights, probability-of-default parameters, and loss-given-default assumptions that determine how much capital a bank must hold against any given asset.

The Network for Greening the Financial System produces the climate scenarios that feed into those formulas.

Together, they control the cost of capital.

But pricing is not enforcement. That function belongs to the Financial Action Task Force. FATF sets the global standards for anti-money-laundering and counter-terrorist-financing compliance — the infrastructure that allows authorities to freeze accounts, block transactions, and exclude institutions from correspondent banking.

In 2021, FATF updated its guidance to explicitly cover proceeds from environmental crimes: illegal logging, wildlife trafficking, waste trafficking, illegal mining. The same compliance machinery built to track terrorist financing can now flag ‘environmental crime’ proceeds. The enforcement layer was already in place. It simply needed new predicate offenses.

Central banks thus sit at the intersection of two capabilities no other institution possesses: the power to set the price of capital through prudential regulation, and the power to enforce compliance through the AML/CFT network.

Legislatures can pass laws. Regulators can write rules. But only central banks — through the FSB-Basel-NGFS nexus and the FATF enforcement layer — can make capital itself conditional on criteria they define.

XIX. The Legitimacy Bridge

The authority to define those criteria flows through a parallel institutional chain.

IIASA (the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, founded in 1972) and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research build the Integrated Assessment Models103. These models calculate emissions pathways, carbon budgets, and transition scenarios.

The same IIASA-Potsdam consortium that produces NGFS scenarios104 for central banks also supplies the modelling for the IPCC and IPBES.

The IPCC synthesises the models into assessment reports105. Those reports define the scientific consensus: how much carbon can be emitted within a given temperature target, how fast emissions must fall, which sectors must transform. The IPCC does not make policy. It defines the parameters within which policy is made.

The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change converts IPCC findings into treaty commitments. The Paris Agreement’s temperature targets106, nationally determined contributions107, and global stocktake108 all derive from IPCC carbon budgets, measured through indicators (normalised surveillance data)109. UNFCCC provides the legal architecture110 — the framework of obligations that governments invoke when they impose transition requirements on their economies.

The biodiversity chain runs parallel. The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)111 synthesises ecosystem science into assessment reports112 — the biodiversity equivalent of the IPCC. The Convention on Biological Diversity113 converts those findings into treaty commitments: the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework114, adopted in December 2022, commits parties to protect 30% of land and ocean by 2030115 and to align financial flows with biodiversity goals.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature provides the operational classifications — the Red List116 that defines which species are threatened, the protected-area categories117, the ‘Nature-based Solution’ standards118.

As the stranded-asset methodology expands from carbon to ecosystems, this chain supplies the authoritative boundaries.

One pipeline, multiple outputs. The same modeling institutes that tell central banks how to price transition risk also tell IPCC and IPBES what the planetary boundaries are.

‘Scientific consensus’ and financial parameters emerge from the same source.

The legitimacy to define environmental boundaries flows from IIASA/Potsdam through IPCC and UNFCCC for climate, and through IPBES and CBD for biodiversity.

Both conventions rely on the GEF as their financial mechanism, which utilises blended finance to leverage private capital.

That private capital is itself steered by supervisory frameworks flowing from the same modeling institutes through NGFS to central banks and Basel.

Public and private financing channels lock into the same underlying architecture.

The two chains converge in supervisory frameworks that make lending conditional on criteria derived from models most people have never heard of.

The end product is a ‘Nature-based Solution’119.

XX. The Next Phase

The next phase is already visible.

If the stranded-asset thesis made carbon reserves into financial risk, the inverse-Leontief model makes ecosystems into financial dependencies.

In December 2025, the ECB published the methodology for Nature Value-at-Risk120 — a framework for converting ecosystem conditions into portfolio-denominated risk metrics. The formula is Hazard × Exposure × Vulnerability, computed across eighteen ecosystem services using the same input-output architecture Leontief developed in the 1930s. The paper states its purpose plainly:

… to lay down the foundations for embedding nature-related risks into supervisory assessments and macroprudential frameworks.

The pathway is explicit. First, internal risk models. Then supervisory review. Then binding requirements — stress-test templates, Pillar 2 expectations, collateral eligibility rules. The ECB has announced that its next step will be ‘the development of a nature-related stress test for euro area banks’.

When NVaR outputs map into probability of default, loss given default, and exposure at default, ecosystem conditions will feed into capital requirements, which will feed into the price of credit across the economy.

The interest rate on a mortgage, the credit line available to an employer, the price of goods on supermarket shelves — all shaped by a coefficient most people have never heard of.

The question now is not whether the methodology moves from occasional paper to supervisory expectation. It is how fast — and what happens when the validation fields in a programmable ledger start checking not just carbon coefficients, but ecosystem-dependency scores.

The documented chain is complete:

Stern Review (2006)

→ CDP disclosure norm (2000–present)

→ Robins/Campanale stranded-asset thesis (2000s)

→ Grantham path-dependence economics

→ Carbon Tracker data (2011)

→ Carney/Villeroy 2015 regulatory pivot

→ TCFD disclosure framework (2017)

→ BlackRock capital-access conditions (2020)

→ EU Taxonomy classification (2020)

→ Green Swan BIS doctrine (2020)

→ GFANZ coordinated commitment (2021)

→ Basel Committee climate principles (2022)

→ Basel Committee SCO60 crypto prohibition (2022)

→ NGFS stress-test parameters (2025)

→ BIS capital-formula mathematics (2025)

→ Bank of England supervisory expectations (2025)

→ Unified Ledger programmable settlement (2023–present).

Each node performed its function. The output is infrastructure that can condition economic life on criteria set outside democratic contest.

The convergence was not organic. Organic intellectual development proceeds through disagreement before consensus, theory tested against data over time, independent researchers discovering each other’s work after arriving at similar conclusions.

What the record shows is different:

Theory and data built in parallel by adjacent institutions drawing from the same funders.

Identical vocabulary appearing in central bankers’ speeches across jurisdictions within weeks.

Disclosure norms pre-constructed and waiting to be formalised.

Personnel rotating through every node of the network.

Financial architecture preceding the treaties it claims to implement — exactly as the GEF preceded the UNFCCC and CBD.

The pattern is not discovery — it is project management. And it’s no longer just about climate.

But then, as the EU told us back in 2020 through its Taxonomy, and the BIS through its ‘Green Swan’ — it never was.

This essay maps primarily to the UNFCCC. The next essay will discuss how similar research is currently progressing in the field of biological diversity.

Find me on Telegram: https://t.me/escapekey

Find me on Gettr: https://gettr.com/user/escapekey

Bitcoin 33ZTTSBND1Pv3YCFUk2NpkCEQmNFopxj5C

Ethereum 0x1fe599E8b580bab6DDD9Fa502CcE3330d033c63c

Too long. Too much assumption of prior knowledge. Too many embedded posts. Why not write 5 or 10 minute (max) summaries and then link to the 40 minute read for those that want to dive deeper?

“We redistribute de facto the world’s wealth by climate policy”

Ottmar Edenhofer UN IPCC official