‘… had another far-reaching aim, nothing less than to create a world system of financial control in private hands able to dominate the political system of each country and the economy of the world as a whole. This system was to be controlled in a feudalistic fashion by the central banks of the world acting in concert, by secret agreements arrived at in frequent meetings and conferences.

The apex of the systems was to be the Bank for International Settlements in Basel, Switzerland, a private bank owned and controlled by the worlds central banks which were themselves private corporations’

‘Each central bank... sought to dominate its government by its ability to control Treasury loans, to manipulate foreign exchanges, to influence the level of economic activity in the country, and to influence co-operative politicians by subsequent economic rewards in the business world‘ —Caroll Quigley, Tragedy and Hope, page 32412.

But we all know that’s conspiracy theory… right?

1. Philosophical Foundations

The roots of modern global governance can be traced to the philosophies of the ancient Greeks—Plato, Socrates, and Aristotle. Each contributes distinct principles that form the bedrock of current governance structures:

Plato: His concept of the philosopher king provides the hierarchical framework for leadership in global governance. Plato’s vision of enlightened rulers parallels contemporary efforts to centralize decision-making within global institutions. His ideal society, described in The Republic, envisions a structured system where rulers, guided by wisdom, govern for the benefit of all. This concept resonates strongly with modern global frameworks where ethics and governance3 are driven by specialized elites.

Socrates: His dialectical method underpins legal and ethical reasoning. Socratic questioning seeks to uncover universal truths through reasoned dialogue, forming the basis for legal systems focused on justice and accountability. The Neo-Kantians, particularly Hermann Cohen4 of the Marburg School, and Paul Carus5 of the Neo-Friesian, advanced these principles by embedding them into frameworks that prioritize justice, equity, and ethical deliberation, influencing modern international law.

Aristotle: His golden mean and Nicomachean Ethics offer a practical guide to balance and virtue. Aristotle’s emphasis on moderation as a virtue has deeply influenced ethical decision-making frameworks. His ideas have been further developed by Hans Jonas, who emphasized responsibility in the context of technology and the environment, Hans Küng, who integrated ethics6 into global dialogues7, and Ken Wilber8, who aligned hierarchical ethics with sustainability and the broader integration of human systems.

Together, these philosophies form the intellectual bedrock for the hierarchical structures, ethical imperatives, and justice-oriented systems seen in modern global governance.

2. From Neo-Kantianism to Tektology

The Baden Neo-Kantian school’s focus on culture intersects with Alexander Bogdanov’s Tektology9, a precursor to systems theory. Tektology conceptualizes society as a ‘human super-organism’10 that can be managed through organizational science. This perspective introduced the idea that systems—whether biological, social, or technological—function according to universal principles. Bogdanov’s work laid the foundation for a systematic approach to governance and management. However, conceptualizing society as a super-organism risks reducing individuals to mere components of a machine, stripping them of autonomy.

This idea evolves into general systems theory11, pioneered by Ludwig von Bertalanffy, and structured hierarchically by Kenneth Boulding12, which seeks to understand the interconnections and feedback loops within complex systems13. The fusion of Bogdanov’s tektology with Proletkult gave rise to Churchman’s systems approach. Churchman’s work extended systems thinking to ethical and organizational decision-making, forming a critical component of modern adaptive management frameworks.

3. Systems Approach and Cybernetic Control

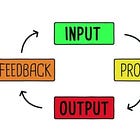

The systems approach emphasizes interconnectedness and feedback mechanisms, forming the backbone of active adaptive management14. Its application in global governance involves the integration of multiple domains, including resource management15, health16, and environmental sustainability. Key elements include:

Input-Output (I/O) Analysis17: Flow analysis of global resources, enabling real-time tracking18 and optimization of energy, water, and material use.

Digital Twins19: Virtual representations of planetary systems that integrate global surveillance20, predictive analytics, and modeling to simulate outcomes and guide policy.

Cybernetic Control: Closed-loop feedback systems enabling real-time adjustments to governance frameworks based on data-driven insights21. Cybernetics, as proposed by Norbert Wiener, focuses on the regulation of systems through feedback and control mechanisms.

Examples of such frameworks include:

Ecosystem Approach22: Top-down land23 and resource management24 that balances ecological health with human needs25.

One Health26: A holistic focus on biosphere health, recognizing the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental well-being.

These frameworks are governed by planetary ethics27, which act as normative inputs into the systems approach28. This raises an urgent question: Who determines these ethical norms, and how are dissenting voices included?

4. Planetary Ethics and the Circular Economy

Planetary ethics provide a moral compass for managing the Earth as a closed system. This perspective aligns with the concepts of:

Spaceship Earth29: Viewing the planet as a finite, self-contained system that requires careful stewardship. Popularized by Buckminster Fuller, this idea emphasizes the need for a sustainable, holistic approach to planetary management30.

Circular Economy31: A sustainable model emphasizing resource efficiency, waste reduction, and the continuous reuse of materials. This approach challenges traditional linear economic models and promotes regenerative systems that align with planetary boundaries32.

Planetary ethics ensure that these approaches are implemented in ways that prioritize long-term sustainability over short-term gains. Nevertheless, they must address the potential for ethical frameworks to be co-opted by powerful actors, turning them into instruments of control rather than empowerment.

5. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

The SDGs33 serve as a dynamic framework outlining global priorities. Adopted by the United Nations in 2015, they address critical issues such as poverty, inequality, climate change34, and biodiversity35 loss. These goals guide ethical, cultural, and educational paradigms, shaping policies and initiatives at local, national, and global levels36.

The SDGs are not static; they will evolve over time to address emerging challenges. Proposed ‘A Long-term Vision for 2050’37 will likely build on the current framework, incorporating advancements in technology, shifts in societal values, and new scientific insights.

6. Control of Agenda-Setting

The ability to place items on the global agenda is a powerful tool. Per A/53/170, General Consultative NGOs hold significant influence over international decision-making38. Key players include:

IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature)39: Defines global conservation priorities, influencing policies on biodiversity, climate, and ecosystem management.

ISC (International Science Council)40: Conducts foundational research, providing the scientific basis for policy and governance.

Collegium International41: Converts scientific findings into ethical frameworks, bridging the gap between knowledge and action.

UNESCO42: Guides education and cultural alignment, ensuring that ethical principles are embedded in societal norms.

WAAS (World Academy of Art and Science): Ensures that artistic and creative endeavors align with global ethical and cultural goals.

The Parliament of the World’s Religions: Uses religion as a tool for moral encoding, as seen in the Vatican’s43 Laudato Si44.

While these organizations serve important roles, their influence risks sidelining democratic processes, raising concerns about accountability and representation.

7. Codification of Ethics

A universal moral framework requires codification into global legislation. The Institute of Noahide Code45, granted General Consultative Status in 2021, emerges as a candidate for this task. Its stated objective is the codification of global ethics, providing a legal foundation for planetary governance. While this initiative seeks to create a cohesive moral framework, its potential for misuse as a tool for centralized control cannot be ignored46.

8. Economic Governance

Economic governance follows a trajectory shaped by the ‘mediator approach’ introduced by Julius Wolf and Eduard Bernstein. This approach evolves through:

League of Nations47: Early international coordination, setting the stage for multilateral48 governance49 for the alleged ‘common good’50.

BIS (Bank for International Settlements)51: A clearing mechanism rooted in Wolf’s pivotal work, facilitating international financial stability.

Keynesian Economics52: Introduced counter-cyclical fiscal policy to mitigate economic volatility.

Monetarism (Friedman): Focused on monetary and fiscal inductance to stabilize economies.

MMT (Modern Monetary Theory): Advocates debt-driven quantitative easing as a tool for economic resilience.

The recent alleged pandemic was almost entirely financed through quantitative easing. And ‘In Tandem’, The Fabian Society’s recent report suggest granting central banks influence over fiscal policy, potentially centralizing power within unelected bodies like the Bank of England53 - an influential member of the BIS. This shift could have profound implications for global economic governance, enabling more coordinated responses to financial crises - but raising concerns about a vast accumulation of power with the few54, entirely outside of principles of democracy.

9. Carroll Quigley’s Vision

Carroll Quigley’s observation on the centralization of power by financial capitalism aligns with this trajectory55. Institutions like the BIS operationalize global goals set by entities such as the IUCN, embedding ethical priorities within economic governance. Quigley’s insights highlight the interplay between financial systems, governance structures, and ethical imperatives56.

10. From Greeks to Global Systems

This synthesis traces a cohesive path from ancient philosophy to modern global governance. Key elements include:

Philosophical foundations (Plato, Socrates, Aristotle).

Neo-Kantian influence and tektology.

Systems theory and cybernetics.

Planetary ethics and resource management.

Agenda-setting by influential NGOs.

Codification of ethics into global legislation.

Economic governance shaped by historical precedents.

11. The Future of Governance

As global priorities evolve, the systems approach will continue to adapt. The integration of ethics, resource management, and economic governance ensures a dynamic yet cohesive framework capable of addressing future challenges. However, this adaptability comes with significant risks. Chief among these is the potential for governance systems to become overly centralized, granting disproportionate power to a small group of institutions and individuals57. This raises profound questions about accountability, and the preservation of democratic ideals.

One critical issue is the reliance on data-driven systems like digital twins and cybernetic control, which are susceptible to manipulation and misuse. As these tools become more sophisticated, they enable the potential for systemic discrimination - without even an opportunity to appeal, as an algorithm will call the shots.

The process of codifying ethics into global legislation also poses challenges. While a universal moral framework aims for cohesion, it has historically justified arbitrary rule and led to some of the darkest periods in history. Ethical norms, once enshrined in law, risk becoming rigid instruments of control rather than flexible guides for coexistence.

Moreover, the increasing influence of NGOs and institutions like the IUCN and ISC in setting the global agenda raises concerns about accountability. While they play roles in research, their unelected nature means they are not directly accountable to the populations they affect, risking a governance model that prioritizes technocratic efficiency over democratic participation.

Economic governance further complicates this picture. The centralization of fiscal policy in institutions like the BIS risks creating a system where financial decisions are made without public oversight. Recent proposals to grant central banks influence over taxation and spending amplify these concerns, potentially leading to a global economic system that is both opaque and unaccountable.

Conclusion

Carroll Quigley, in Tragedy and Hope, famously warned of the consolidation of power within financial capitalism, where an elite few could dominate global systems under the guise of efficiency and progress. His insights resonate deeply with the current trajectory of global governance. Quigley highlighted the tendency of such centralized systems to operate without transparency, often bypassing democratic processes to serve the interests of a narrow oligarchy58.

The frameworks described here carry the risk of fulfilling Quigley’s dire prediction. Institutions like the BIS, operating alongside influential NGOs, exemplify the potential for technocratic governance that prioritizes centralized control over public accountability. The codification of ethics, the use of cybernetic systems, and the reliance on data-driven decision-making further amplify these risks.

Quigley’s insights highlight the need for vigilance against centralized power. While integrating systems theory, planetary ethics, and economic governance offers opportunities to tackle global challenges - legitimate or not59 - it also raises questions about global leaders' commitment to democratic principles.

It is hard to describe Quigley's writing as a warning when he states that he agrees with it except for the fact that it wishes to remain secret and that he feels that it should be put out there.

QE1 or QE2???