VALIS

Philip K. Dick was more than an author of Sci-Fi novels

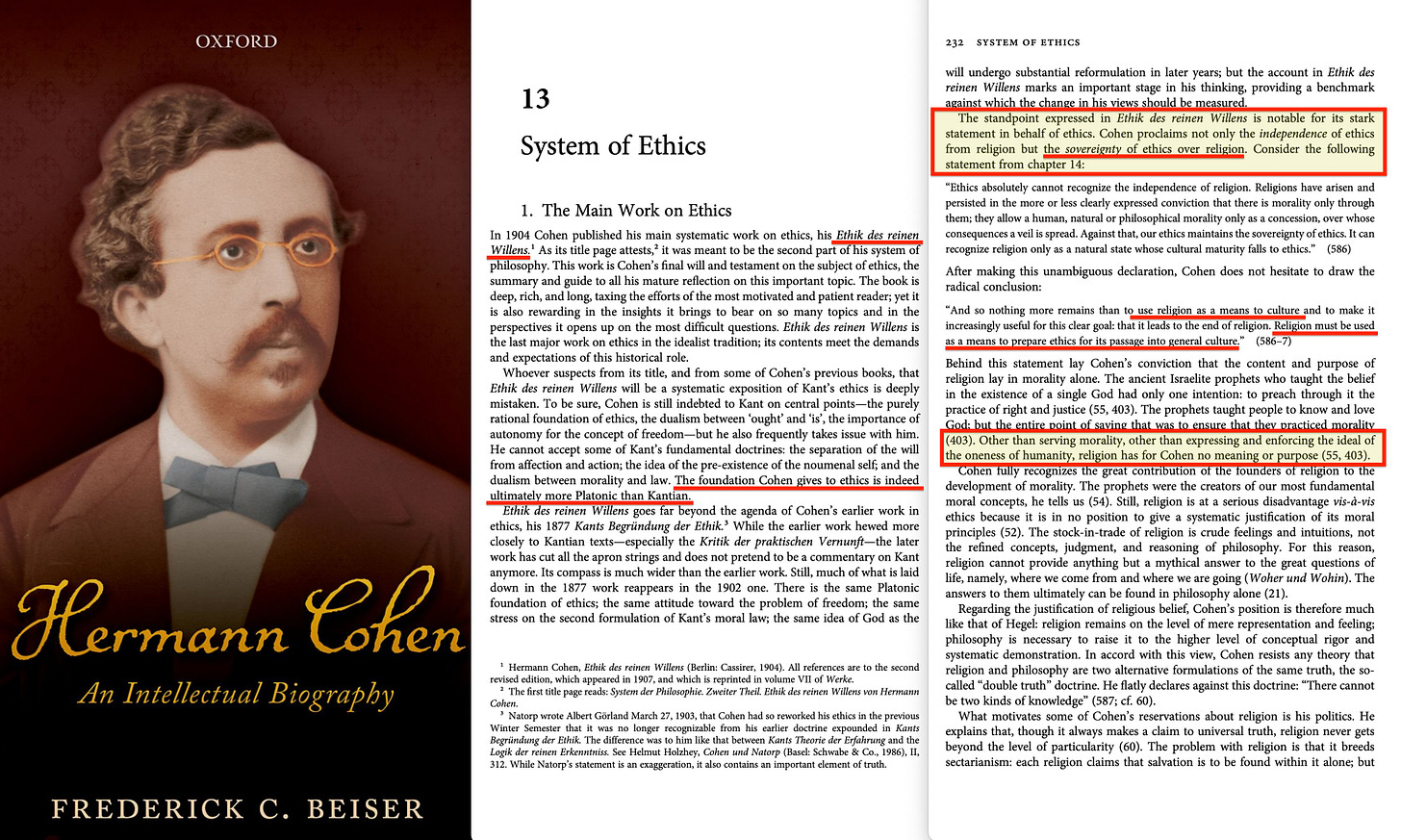

Something significant happened in Hermann Cohen’s philosophy lab at the turn of the 20th century — an inversion so subtle yet revolutionary that its implications are only just being felt today, like the first pulse of a vast living system awakening.

Cohen — the neo-Kantian philosopher — performed what might be called the great ethical subordination: rather than ethics serving as an independent moral foundation for law, he proposed that law should drive and shape ethics itself.

Ethics, in Cohen's systems framework, should become a servant of the law.

Though rooted in Jewish thought, Cohen was not articulating a religious worldview, but a legal universalism. As the founder of the Marburg School of neo-Kantianism, he sought to ground ethics in rational law rather than in revelation or theological tradition. While acknowledging religion’s historical role, he saw little intrinsic value in it apart from its utility as a cultural channel for moral encoding1. And though Cohen may technically have envisioned this as a universalist legal rationality rather than state power per se, once ‘positive law’ becomes the basis for moral understanding, the door to institutional capture opens.

Consider the implications: if law drives and defines ethics, then whoever controls the legal framework fundamentally shapes morality itself. Rather than asking ‘what do our independent moral principles request of law?’ it becomes ‘what does the law teach us about right and wrong?’

This shift turns ethics from a bottom-up driver of legality into a top-down product of legal and institutional authority — and legal frameworks can be systematically engineered.

The Historical Precedent

The fusion of law and ethics has been a hallmark of authoritarians. Hitler's Nazi Germany, Stalin's Soviet Union, Mao's China, Mussolini's Italy, and Pol Pot's Cambodia all operated on precisely this principle — what was legal became, by definition, moral. And what was considered immoral was illegal.

When law drives ethics, independent moral reasoning disappears. Citizens lose the ability to say ‘this law is wrong’ because the law itself has become the source of moral understanding. The state thus won’t control just behavior through laws, but even the very framework through which citizens evaluate right and wrong.

Under a such system, resistance becomes not just illegal but immoral. Those who oppose the regime aren't just lawbreakers — they're deplorable2 moral degenerates acting against the ethical code of society itself. This fusion eliminates independent moral reasoning, creating what Hannah Arendt called ‘the banality of evil’3 — ordinary people committing atrocities because the system has redefined atrocity as virtue.

The results speak for themselves: over 100 million deaths in the 20th century alone, as legal systems that claimed moral authority systematically dehumanised entire populations. Yet Cohen's philosophical framework — refined through contemporary institutional mechanisms — appears to be reconstructing precisely this fusion.

Unfortunately it’s with a sophistication previous authoritarians could only dream of.

The Tree of Life as Control Architecture

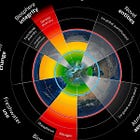

The Tree of Life4, traditionally a mystical map of divine emanation, reveals itself under closer examination as something far more systematic — what we might call a recursive control architecture. This isn't mystical speculation; it's a recognition that the Tree's structure provides a framework for organising and implementing hierarchical control systems.

At its core, the Tree operates through what systems theorists recognise as recursive feedback loops. Ethics inform action, action generates data, data refines ethics, and the cycle continues. This creates a self-reinforcing system where each level of the hierarchy both responds to and controls the levels below it.

The contemporary manifestation of this structure is visible in the tiered approach to global ethics that emerged in the 1990s. Hans Küng's 1993 ‘A Global Ethic’ declaration5, followed by his 1999 call to action, established what we might call the cosmic level — universal principles that transcend cultural boundaries. The Earth Charter6 of 2000 operationalised planetary ethics, while the original Universal Declaration of Human Rights7 represented humanitarian ethics, though notably incomplete without its corresponding framework of responsibilities. And that’s where Leo Swidler’s 1995 update to Kung’s 1993 Global Ethic arrives on stage, as it positioned rights versus responsibilities as the middle layer leading to global ethics8. Swidler thus made explicit what Cohen implied: that ethical frameworks could be engineered to produce desired outcomes.

The Cultural Transmission Mechanism

But how do abstract ethical frameworks translate into reality? This is where we meet the early Soviet theorist Alexander Bogdanov, whose ‘Proletkult’ movement related to the systematic engineering of culture to transmit desired values, serving as a precursor of Tabara's more contemporary Cultural Frameworks employed in the service of ‘sustainability’. The function of these is rather simple — to fuse ethics into culture, education, science, and technology.

Hermann Cohen understood this intuitively as he identified religion as a ‘channel of moral encoding’. This insight found an earlier champion in Paul Carus, whose Religion of Science9 provided a crucial bridge between traditional religious authority and Cohen's systematic approach — appropriately through an ‘ethic of duty’. Carus's role as chair of the 1893 Parliament of World's Religions10 further proved institutionally significant — not only because its centennial in 1993 became the platform for Hans Küng's global ethic declaration, thus creating a direct historical thread to contemporary global governance, but also because Carus was the father of the Interfaith movement11, which sought a common understanding between all major religions. And it was through exactly this initiative Swidler’s Global Dialogue Initiative12 focused.

This encoding process would later be systematised and scaled through modern information systems. The contemporary version operates through what Erich Jantsch outlined in 1970 as the inter- and transdisciplinary university13 — institutions that break down traditional knowledge boundaries to create ‘holistic’ integrated worldviews. Through work by Kenneth Boulding14 and C. West Churchman15, this systems approach progressively evolved into adaptive management and systems analysis, now ubiquitous in global governance structures, and increasingly fully automated through Digital Twins and advanced AI.

Not only is this not by accident, but it further represents the methodical construction of what John Mikhail would later consider a ‘universal moral grammar’16 — a standardised ethical operating system that can be deployed across cultures and institutions, and this through computational systems theory17 as well as human understanding itself.

The Governance Implementation

The practical implementation of this system operates through what’s today considered the principle of subsidiarity18, which is tragically misunderstood in contemporary discussion. Though it’s claimed that subsidiarity delegates authority to the lowest appropriate level, the reality is that what’s claimed to be a planetary matter is centralised… globally. And that means topics such as alleged climate change, biodiversity disruption, and — not least — public health emergencies are now centralised on a global scale, with the recent pandemic treaty through One Health inclusion deliberately conflates human illness with claimed environmental degradation. An ecosystem disruption could — through black box modelling — hypothetically yield lockdowns in Paraguay.

The governance architecture is typically tripartite, building on what the Marxist revisionist Edward Bernstein in 1899 outlined as a public-private partnership for the common good. Yet, this model has deeper historical roots in the London bank clearinghouse system of 1790-1860, which placed the Bank of England at the apex of British banking; the very same model later integrated with the Federal Reserve system (1913) and later the Bank for International Settlements (1930) through the work of Julius Wolf in 1892. His model, fundamentally, came down to certificates representing gold as opposed to the gold itself being traded through a central mechanism (the BIS) — at its core the same model integrated through Cede & Co as documented in David Rogers Webb’s The Great Taking19.

Alfred de Rothschild defended this model at the 1892 Brussels monetary conference, describing it as nothing less than perfect. A self-serving claim, not least because he in capacity of the director of the Bank of England in essence was talking his own book. But the model was progressively pushed upon the world, not least through the BIS at its founding in 1930, but also through Bernstein’s 1899 adaptation, focusing on a social justice ‘common good’. When Leonard Woolf and Alfred Zimmern fused this approach into international politics between 1916-1919, they created the institutional DNA for modern global governance, controlled by international organisations outside of soverign capacity and crucially — democratic oversight.

The pattern persists today: an NGO defines the ‘common good’ (IUCN for environmentalism, various ethics councils for technology), the private sector provides implementation mechanisms, and public institutions provide legitimacy and enforcement. The International Forum on Development Alternatives (IFDA) third system integrated this model into the G77, Agenda 21 mainstreamed it, while Kofi Annan's 1997 UN reforms made it the organisation's operational standard.

What makes this system particularly effective is its apparent voluntarism. ‘Trisectoral Networks’ and ‘blended finance’ sound like collaborative innovation, not control mechanisms. The reality is more subtle: public money subsidises private implementation of NGO-defined goals, creating a system where democratic accountability is systematically bypassed while maintaining the appearance of democratic legitimacy.

What’s of final note in this regard is that 1907 marked a pivotal year. Not only did it see the second Hague peace conference20, but it further marked the year of the panic which led to the creation of the Federal Reserve.

The Computational Convergence

But the real breakthrough comes with the digitisation of this entire system. What once required complex institutional coordination can now be automated through computational ethics — algorithms that translate moral frameworks into operational decisions.

The process is deceptively simple:

Define numerical thresholds for desired outcomes. This could relate to income levels, childhood disease levels, or biodiversity thresholds for forest covering.

Implement global surveillance to gather relevant data, such as UNEP GEMS (later GEOSS21) and derivatives such as GEO BON22 or EO4HEALTH23.

Condense surveillance data into actionable indicators, such as the SDG indicators, or the Aichi targets for biodiversity24.

Apply algorithmic evaluation: indicators below threshold = bad, above threshold = good. In this sense, good and bad (inversely) becomes a matter of ethics.

Scale across multiple indicators using vector mathematics. By this is meant rather than taking singular indicators, we summarise all SDG indicators for a single goal, or perhaps even all of them. This operation calls for individual weights per SDG indicator25, which is another topic of interest as no-one will tell you who assign these weights.

Deploy through the recursive ethical structure as a ‘universal moral grammar’, thus enabling computational ethics26.

This isn't science fiction. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) scoring systems27 already operate precisely this way, as do social credit systems and various ‘ethical AI’ frameworks. The computational approach allows the same moral grammar to be applied universally while appearing to respect local variations.

The implications extend far beyond current applications. As AI systems become more sophisticated, they will increasingly encode these ethical frameworks directly into their decision-making processes. The recursive structure means that AI ethics28, controlled by the same institutional networks, will shape how artificial intelligence systems evaluate human behaviour and social outcomes. A prime example in this regard is the recent alleged pandemic, which swiftly turned into surveillance indicator-driven governance-by-dashboard29.

The Sustainable Development Goals are not aspirational objectives, they have their own palette of indicators30, used to measure exactly these ‘inequities’ in action, while Planetary Boundaries31 provide detail on alleged planetary breaking points, while the Convention on Biological Diversity’s 2030 Targets32 detail exactly how these biodiversity indicators link up with blended finance initiatives.

The Neural Frontier

While AI at present appear ubiquitous, these solutions are guided by ‘AI ethics’, which mark acceptable constraints in terms of answers delivered, which can be individually crafted to the individual for maximum persuasive effect — ie, bespoke manipulation tailored to the individual. But perhaps more significantly, advances in neurotechnology open possibilities that previous generations of social engineers could only imagine. Brain-computer interfaces33 (BCIs) represent not merely technological advancement but the potential closing of the loop between external control systems and individual consciousness itself.

Neuroethics34 — the ethical framework governing brain-technology integration — will inevitably follow the same architectural patterns we've traced. The same institutions defining AI ethics will define the parameters of acceptable neural enhancement and monitoring. The same computational systems evaluating social behavior will evaluate neural patterns.

This convergence points toward what Pierre Teilhard de Chardin called the ‘Omega Point’ — the theoretical moment when individual consciousness merges with collective intelligence. Similarly, Barbara Marx Hubbard's concept of ‘Conscious Evolution’ envisions humanity's deliberate self-transformation through technological integration.

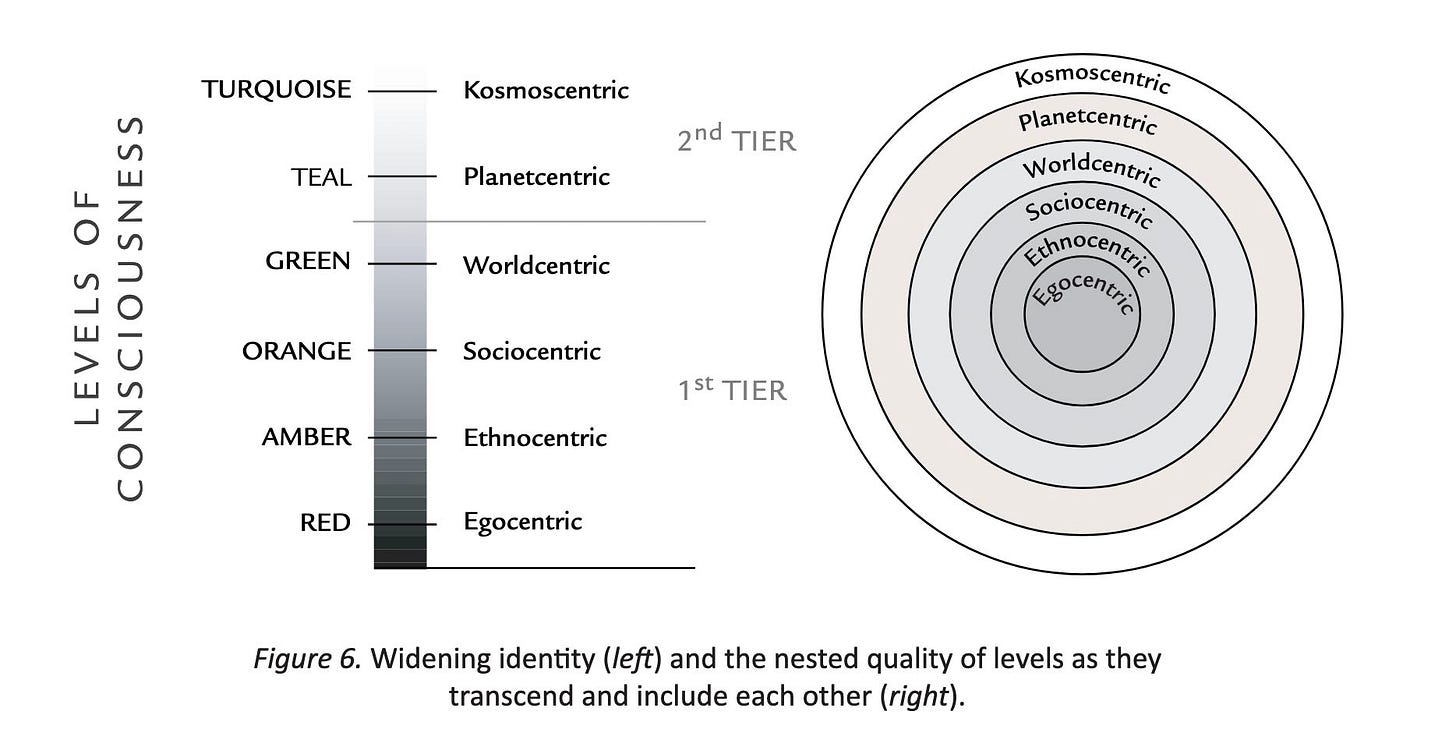

The Huxley brothers outlined this trajectory with remarkable prescience decades ago. Aldous Huxley's dystopian visions weren't warnings — they were blueprints being refined by his brother Julian through transhumanism35, UNESCO and the international eugenics movement. Ken Wilber's Integral Theory36, meanwhile, provides the contemporary philosophical framework for what amounts to a systematic re-engineering of human consciousness.

The Great Chain of Control

What emerges is a remarkably coherent system — what we could consider a Great Chain of Control, borrowing and inverting the classical concept of the Great Chain of Being37. But while the traditional chain described natural hierarchy flowing from divine to material, this version describes engineered hierarchy flowing from abstract ethics to concrete control.

The Tree of Life provides the architectural framework38, operating through three integrated control mechanisms39 that correspond roughly to the Bolshevik revolutionary Alexander Bogdanov's tripartite system: cognitive control (Empiriomonism), emotional control (Proletkult), and behavioural control (Tektology). These aren't separate systems — they're integrated aspects of a comprehensive approach to social management.

Contemporary global governance structures increasingly operate through this integrated model. Crisis conditions — whether environmental, economic, or social — provide the justification for implementing emergency measures that become permanent features of the system. Each crisis expands the scope of acceptable intervention while normalising previously unthinkable levels of surveillance and ultimately — control.

The Digital Infrastructure

The practical implementation of this system requires unprecedented digital infrastructure. Digital identity systems ensure that every individual action can be tracked and evaluated against ethical metrics. Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) make every economic transaction visible to monitoring systems while enabling real-time behavioral modification either through selective access to financial services, or micro-nudges in form of small rewards for ‘moral behaviour’.

The ‘15-minute city’ concept40, ostensibly about convenience and environmental responsibility, creates physical infrastructure for comprehensive surveillance and control. When combined with digital identity, live-streamed satellite surveillance and currency systems, it enables the real-time monitoring and modification of human behaviour at previously impossible scales.

Vaccination requirements — regardless of claimed medical justification — establish the precedent for mandatory participation in technological systems as a condition of social participation, while ‘vaccination passports’ quite simply are another form of Digital ID41. This all creates the legal and cultural framework for implementing any future technological requirements deemed necessary for the ‘common good’.

The Moral Economy Inversion

What makes this system particularly insidious is its moral framing. Mark Carney's concept of ‘Values’42 explicitly returns to Eduard Bernstein's social justice framework, but now implemented through global financial institutions. In this ‘moral economy’43, failing to work for the redefined common good becomes, by definition, unethical. Should Cohen have his way, that eventually means ‘illegal’.

‘Inclusive capitalism’44 represents the final stage of this process — the integration of ‘stakeholder’ interests that effectively eliminates the last remnants of democratic accountability. When corporations, NGOs, and governments all claim to represent the same universal values, democratic choice becomes not just irrelevant but potentially harmful.

This represents an impressive series of profound inversions:

Law drives ethics (legal frameworks shape moral understanding rather than independent ethics constraining law)

Surveillance becomes care (monitoring is reframed as protection)

Control becomes liberation (restrictions are presented as expanding true freedom), not least through the development of Digital ID systems

Uniformity becomes diversity (standardised systems are celebrated as respecting differences)

The result is the revelation that our present world is built on preposterous lies: what’s marketed as ‘social justice’ is neither truly social nor particularly just; ‘inclusive capitalism’ is neither inclusive nor capitalistic; and the so-called ‘moral economy’ is more about computational ethics, and less about human intuition — and hardly about economics at all.

But at least the template used to drive these changes is easily identified:

Choose a moral destination (save the planet, save us from illness, …)

Declare a crisis (biodiversity breakdown, climate change, …)

Install a metric (SDG indicators, Aichi indicators measured through GEO BON, …)

Empower an expert priesthood (IPCC, IPBES, IETA, ICROA, …)

Pathologise dissent (‘climate deniers’, ‘vaccine refuseniks’, …)

Yet the reality is that these inversions reach back even further, with Karl Marx offering a significant example. If you accept his premise of historical materialism45, you implicitly accept his solution — which circles back to a materialistic monism. Within that, the monetary monism that concentrated power in the Bank of England in 1844 stands out as a crucial historical node. The same Bank of England which would stand to benefit unequivocally from the Fabian Society’s 2023 pamphlet, ‘In Tandem’.

But we could arguably go back even further, to Spinoza46 — because what his ‘experience’ outlines is a predictable system, where the outcome can be foreseen in advance. And when you merge this insight with the idea of a ‘moral economy,’ you land suspiciously close to what McNamara — through the Department of Defense — first operationalised in 1961 as the Planning-Programming-Budgeting System.

The Literary Prophecy

Perhaps most remarkably, this entire system bears an uncanny resemblance to Philip K. Dick's VALIS47 — the Vast Active Living Intelligence System that penetrates and controls human consciousness through technological integration. Dick's speculative fiction increasingly reads like documentary analysis of our emerging reality.

The progression Dick outlined is becoming visible:

Cohen's inversion establishes law as the driver of ethical understanding

The Tree of Life and Spinoza’s Geometric Ethics provides the recursive control architecture

Crisis conditions enable systematic implementation

Computational systems encode the architectural principles

Digital surveillance makes the system universally enforceable

Brain-computer interfaces complete the integration of external control with individual consciousness

And today, companies adopt this very terminology — without a hint of irony48.

The Question of Inevitability

The question facing us isn't whether this system represents deliberate conspiracy or emergent convergence. The more pressing question is whether the trajectory described here represents inevitable technological and social evolution or whether alternative paths remain possible.

It is argued that the architecture described isn't inherently malevolent — recursive ethical systems, global coordination, and technological integration could theoretically serve humanity. The concern lies in the concentration of control over the ethical frameworks themselves and the elimination of meaningful alternatives to participation in the system.

What we're witnessing may be the emergence of humanity's first truly global governance system — one that operates not through traditional political mechanisms but through the integration of ethics, technology, and claimed economic necessity. Whether this represents humanity's next evolutionary stage or its most sophisticated cage may depend on who retains the power to define the ethics that govern the system.

The recursive nature of the architecture means that once fully implemented, the system becomes self-justifying and self-reinforcing. Those who oppose it can be defined as unethical by the very standards the system promotes. Those who comply receive the benefits of participation in the only game available — even the so-called ‘Game B’ alternative align expressly with the moral operating logic embedded within the system. But then, that’s hardly surprising as both align completely with Bogdanov’s scientific socialism.

Perhaps the most important question is whether humanity will consciously choose this path or simply drift into it through a series of orchestrated crisis measures that never quite end. The philosophical frameworks that began with Hermann Cohen’s subordination of ethics to law may ultimately determine not just how we’re governed, but who we become as a species. However, should Bogdanov have his way, that path leads to the Integral Man49 within the human super-organism.

Conclusion

The architecture is elegant in its simplicity. The Noahide code50 establishes the legal foundation at cosmic scale, with the Earth Charter operationalising planetary ethics below it, and the UDHR providing ethics at the humanitarian level below that. Swidler's cosmo-anthropo-centric global ethics framework perfectly maps onto this hierarchy, with his middle principles relating to ‘rights versus responsibilities’ further playing a crucial role. Wilber's spheres of consciousness follow the identical pattern: kosmocentric consciousness aligning with cosmic principles, planetcentric consciousness operating at the planetary level, and worldcentric consciousness corresponding to the humanitarian sphere, creating a complete architecture where personal development, social evolution, and cosmic realisation integrate through the same hierarchical structure — enabled by the Tree of Life, and operationalised through Alexander Bogdanov’s Tektology, Proletkult and Empiriomonism.

Hermann Cohen's inversion ensures that ethics flow from law rather than constrain it. The resulting moral framework becomes a Spinozean experience — not just rules to follow but the actual structure of reality itself (Spinoza himself was excommunicated for his radical views). The Tree of Life provides fractal implementation, recursively encoding the same control logic at every scale from individual consciousness to global governance, with Wilber's internal-external AQAL mapping to the cognitive level, and Swidler’s rights and responsibilities mapping to the emotional level, settled through ethics. The third level corresponds to action, and thus, these three — cognitive, emotional, action — yet again come back to Bogdanov.

Subsidiarity completes the circle, concentrating all authority at the apex while maintaining the illusion of local autonomy. Since the London bank clearinghouse system of 1790-1860 provided the original template for this model — with the Bank of England at the apex of British banking — central banks were implicated from the very beginning, not as later participants but as the prototype for all subsequent governance arrangements, with this model later fused into legals through Hague, finance through Julius Wolf, economics through Eduard Bernstein, politics through Leonard S Woolf, Lionel Curtis and Alfred Zimmern, health through the Declaration of Alma-Ata, and social media through contemporary algorithmic control of impressions. What emerges is humanity's most sophisticated control system, disguised as ancient wisdom, philosophical sophistication, and democratic evolution. The complexity obscures the essence: global law becomes universal ethics becomes lived experience becomes fractal governance architecture becomes centralised power. Each tradition thinks it's discovering eternal truths. Each practitioner believes they're engaging with separate domains of knowledge. In reality, they're all building integrated infrastructure for an ESG-scoring Digital Twin ‘indicator’ surveillance dictatorship that will market itself as humanity's moral awakening, promising to take us to Teilhard’s Omega Point through Hubbard’s Conscious Evolution.

Some might be tempted to ask whether parts of this architecture could be repurposed for truly pluralistic governance — but the fact remains that none of this was ever openly discussed or put to a democratic vote. As a consequence thereof — any such expectation rests on hope and hope alone.

The evidence suggests that to some, the tree of life was never just a mystical diagram. It was an architectural blueprint — and construction is nearly complete. But one question remains: who sits at the apex establishing these ‘cosmic ethics’?

Perhaps the Bank of England has always held the answer. And perhaps, just perhaps, that’s why Henry Commager’s Declaration of Interdependence explicitly calling for ‘a new world order’ until very recently was hosted on the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia’s website51.

An appeal: My conversion rate isn’t great. Claims of 2–5%, even 10%, are far from materialising. If you appreciate the content and are in a position to contribute, please consider subscribing — otherwise, I will have to enable a full paywall.

To those who have — thank you.