From Bellagio to Basel

Impact Investing

Between 2008 and 2017, a new kind of financial system quietly took shape. Looking back, what were sold as separate trends — the rise of sustainable finance, the momentum behind impact investing, surprising shifts in central bank policy — were actually connecting parts of a single machine.

That machine, now almost fully operational, holds immense power.

It decides which industries get loans, what assets sit on bank balance sheets, and which transactions are even allowed to clear. And the rules it follows were written almost entirely out of public view, far from any democratic debate.

This system wasn’t built by accident. It didn’t grow organically from the market or from scientific agreement. In fact, the policy blueprints were drawn up before the ‘science’ was ‘settled’. The tools to measure ‘good’ investments were already in place before most people were even using the language. And if you trace its development, you see the same names again and again — a consistent cast of families, foundations, and institutions at every turning point.

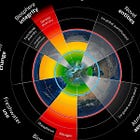

The real revelation is in the structure. The same machinery created to funnel money toward ‘positive’ impact is now being used to starve other assets of capital. Impact investing and the creation of stranded assets are two sides of the same coin — one pulls money in, the other pushes it out. The taxonomy that labels an activity ‘green’ automatically defines everything else as ‘brown’.

It’s the same system, the same wiring. Only the current has been reversed.

The Coordinated Development of Climate Finance

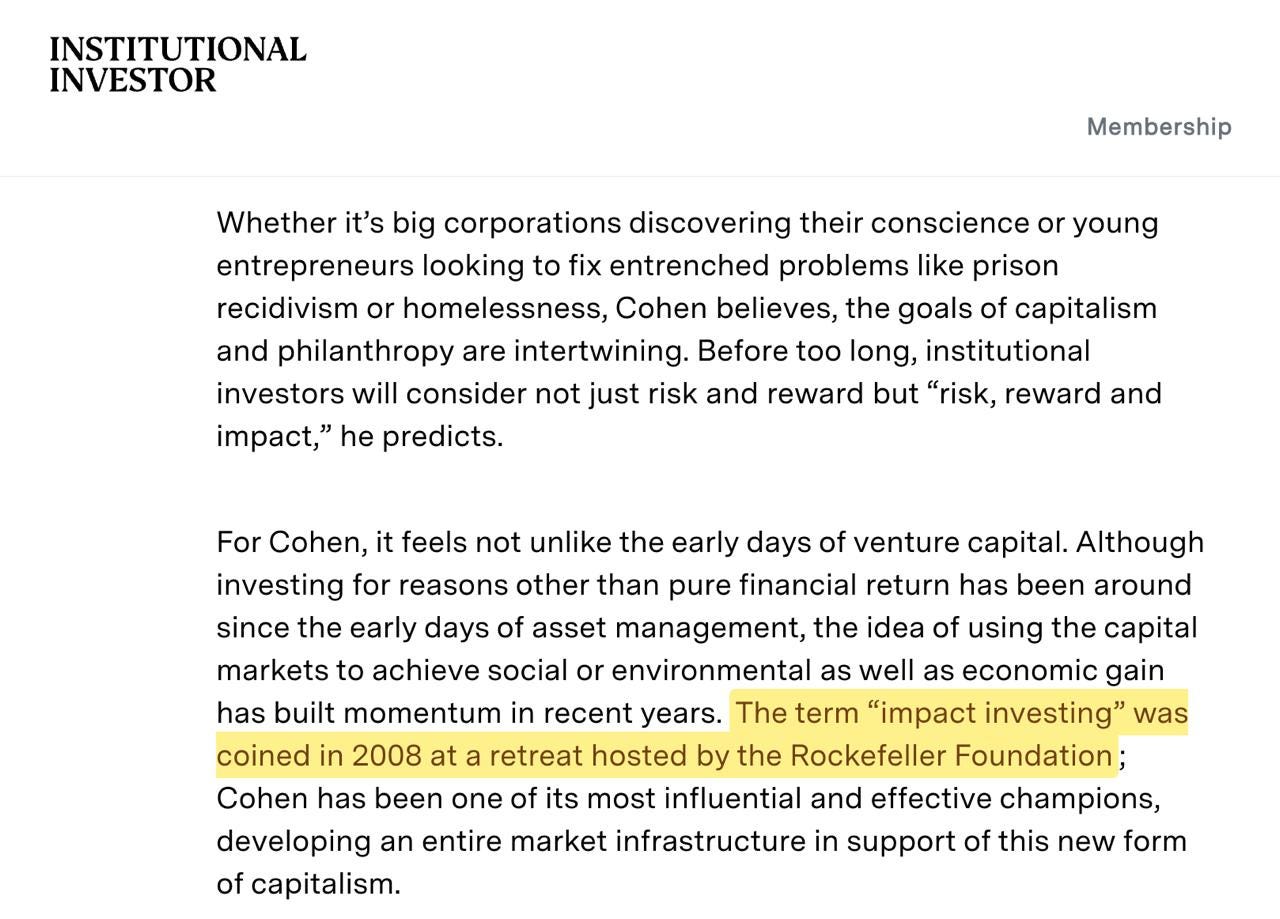

In 2008, a quiet gathering at the Rockefeller Foundation’s Bellagio Centre in Italy gave a name to an idea: ‘impact investing’. The premise was that capital could pursue financial returns while also producing measurable social or environmental good. But to make that idea real, something crucial was missing — a standardised way to measure those non-financial impacts and hardwire them into financial decisions.

Four years later, a parallel effort began at the University of Oxford. The Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment launched its Stranded Assets Programme, funded by the Rothschild Foundation. Key meetings were held at Waddesdon Manor, the Rothschild estate in Buckinghamshire. There, between 2014 and 2017, contributors developed the framework that would define ‘stranded assets’ — initially fossil fuel reserves destined to become worthless due to regulatory or market changes.

The sequence here is important. The 2014 forum at Waddesdon Manor set the stage. A year later, in September 2015, Mark Carney, then Governor of the Bank of England, stood at Lloyd’s of London and issued a watershed warning: up to a third of the world’s fossil fuel reserves might be unburnable — stranded. His speech echoed the Waddesdon framework nearly word for word, explicitly citing the ‘unburnable carbon’ analysis from the Carbon Tracker Initiative. Within a few years, that conceptual warning had become official policy, as the Bank baked climate risk scenarios into its stress tests for banks and insurers.

This momentum converged at the Paris One Planet Summit in December 2017. There, Carney helped launch the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS). What started with eight central banks has since grown into a powerful consortium of 134 members, creating a shared playbook for climate risk.

The scenarios they now produce directly shape the rules of finance — determining how much capital banks must hold, where they can lend, and what assets institutional investors are effectively permitted to buy.

The Evidence of Coordination

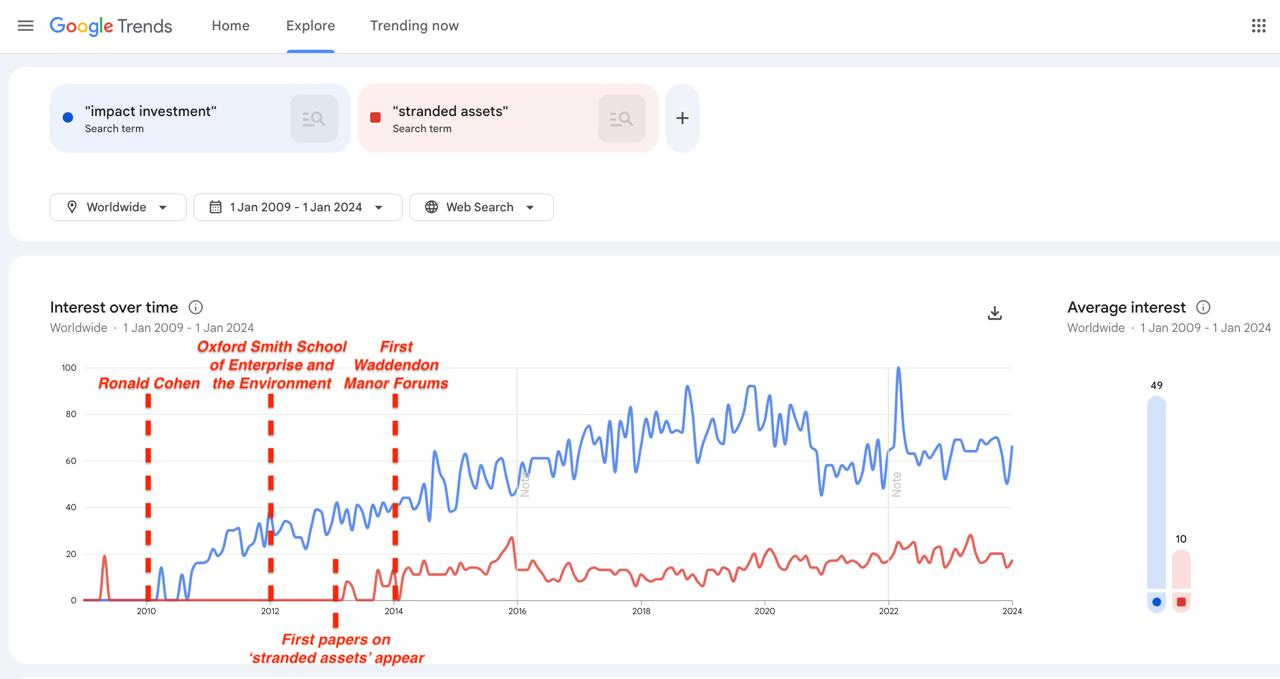

Looking at the search data, the timeline feels too precise to be accidental. From 2009 onward, Google Trends shows a telling pattern. ‘Impact investing’ begins its climb around 2010 — right after the term was coined at that Rockefeller retreat. Similarly, searches for ‘stranded assets’ appear from nowhere in 2012, the exact year Oxford launched its programme on the subject.

These two curves don’t just rise — they move in lockstep. Interest in both terms ticks upward together through 2014, the year of the first Waddesdon Manor forum, and then accelerates in tandem after that.

This isn’t the chart of ideas bubbling up from public debate. It reads more like a coordinated rollout.

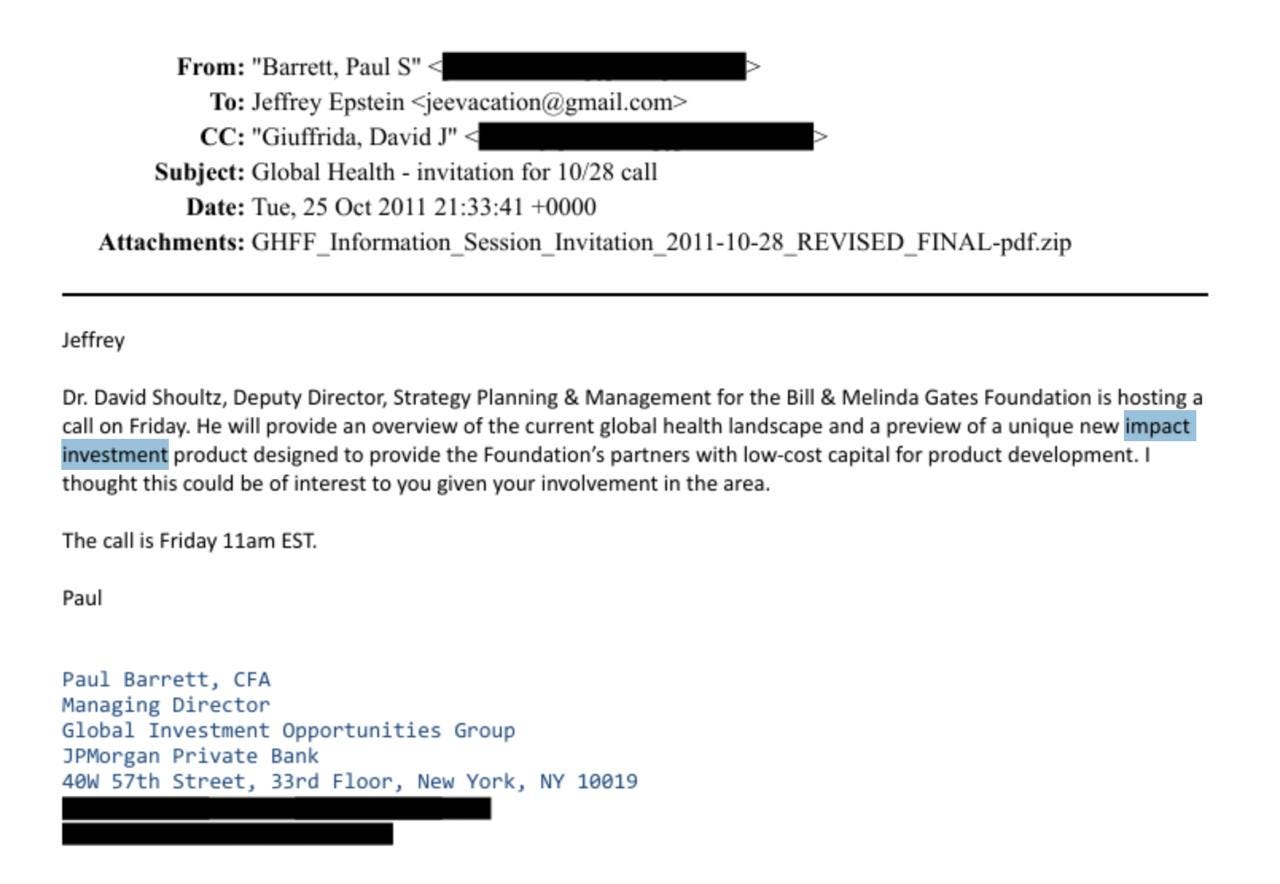

The plans were being drawn up in private long before they entered the public conversation. An email dated 25 October 2011, from Paul Barrett of JPMorgan Private Bank’s Global Investment Opportunities Group to Jeffrey Epstein1, invited him to a call hosted by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation concerning ‘a unique new impact investment product designed to provide the Foundation’s partners with low-cost capital for product development’.

The terminology and mechanisms were circulating within elite networks three years before stranded assets entered mainstream discussion and six years before the NGFS coordinated central bank adoption.

By early 2012, the framework had already reached the highest levels of government. In April, then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton hosted a conference on impact investing at the State Department, using her keynote to champion the model. That same year, across the Atlantic, Big Society Capital launched in the United Kingdom with £600 million in committed funds.

The rollout was transatlantic and governmental from the start, with Washington and London moving in lockstep a full year before Ronald Cohen’s G8 Taskforce formalised the international coordination2.

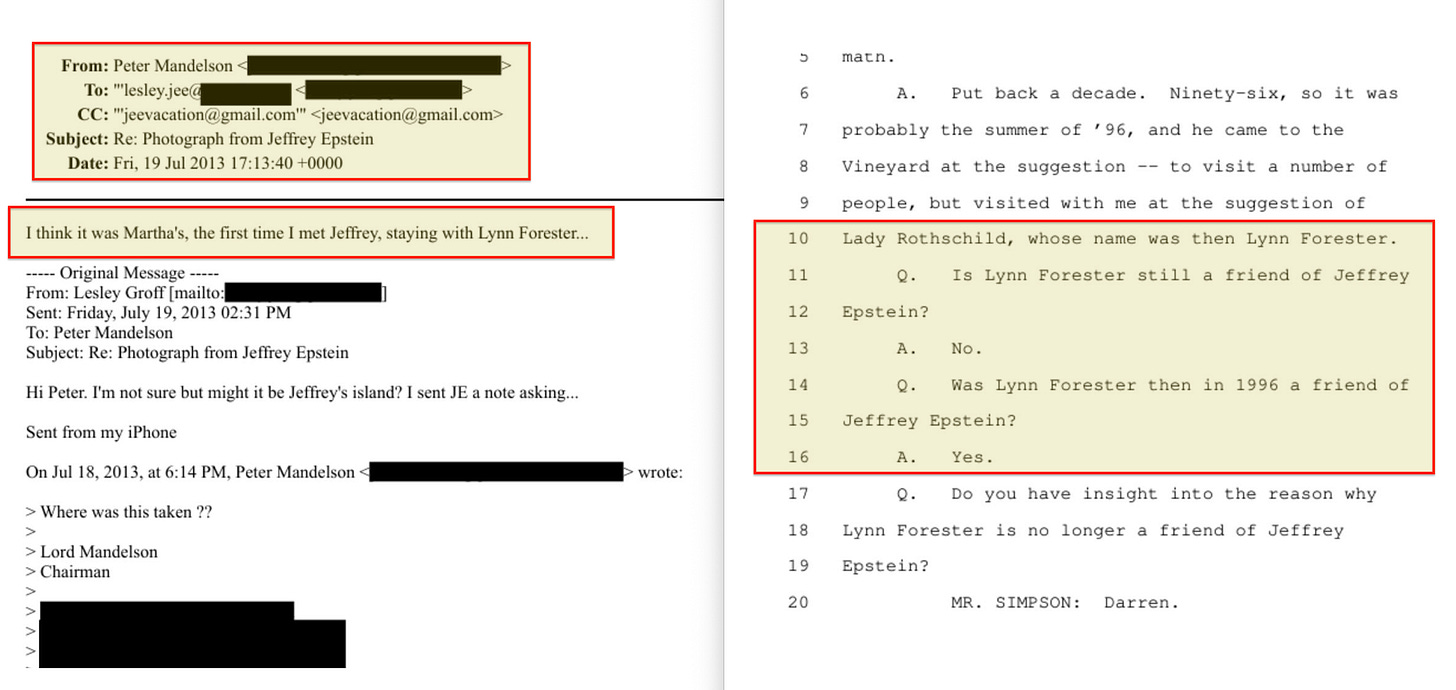

The networks connecting these developments are documented in legal proceedings. Deposition testimony confirms that Jeffrey Epstein visited Martha’s Vineyard in the summer of 1996 ‘at the suggestion of Lady Rothschild, whose name was then Lynn Forester’3. A July 2013 email from Peter Mandelson, then a Labour peer and former European Commissioner for Trade, recalls first meeting Epstein while ‘staying with Lynn Forester’4.

Lynn Forester de Rothschild would subsequently found the Coalition for Inclusive Capitalism in 20125 and co-found the Council for Inclusive Capitalism with the Vatican in 20196, meaning the social networks preceded the institutional architecture by decades7.

The Division of Labour

The blueprint for this system didn’t appear by chance. Its development reveals a consistent thread of coordination, woven through institutions and across generations of the same influential families.

The Rockefeller network, in particular, supplied much of the American groundwork. Their interests funded the Conservation Foundation from its start in 1948. Later, Laurance Rockefeller helped shape the Council on Environmental Quality under President Nixon — the very body that brokered the 1972 US-USSR environmental agreement.

That pact did more than foster cooperation; it essentially merged American and Soviet policy frameworks, creating a template for international climate governance. Rockefeller philanthropy continued to bankroll climate science for decades, setting the stage for the family’s foundation to later convene the 2008 Bellagio retreat. It was there they coined the term ‘impact investing’, effectively rebranding this longstanding architecture for the modern financial era8.

Ronald Cohen was the figure who translated this framework into concrete policy. His work began in Britain, where as chairman of the UK Social Investment Task Force starting in 20009, he helped build the legal and financial plumbing that would eventually create Big Society Capital in 201210.

Having cemented the model at home, he then took it global. From 2013, he chaired the G8 Social Impact Investment Taskforce, tasked with scaling the British blueprint across the world’s largest economies11.

The Rothschild influence unfolded through distinct family branches over more than a century, each contributing a critical piece.

In 1892, Alfred de Rothschild, a former director of the Bank of England representing the United Kingdom, addressed the Brussels International Monetary Conference. There, Julius Wolf proposed a gold-backed clearing house mechanism, a scaled version of the very model which placed the Bank of England at its apex — and it was this concept which would later provide the foundational template for the Bank for International Settlements, the institution presently developing a next-generation financial ‘Unified Ledger’.

In a different sphere, Walter Rothschild embodied another form of systematisation. He was the naturalist who built a global taxonomic infrastructure to classify the world’s species12. He was also the named recipient of the 1917 Balfour Declaration13 — biology and territory fused in a single figure.

Miriam Rothschild continued this lineage of influence at the intersection of science and governance. In 1942, she contributed to the ‘Science and Ethics’ correspondence, a follow-on from ‘Science and World Order’ which was a 1941 conference promoting nothing short of scientific socialism.

Just a few years later, in 1948, she co-founded the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) — the organisation that continues to draft the global legal frameworks designating protected lands worldwide.

Meanwhile, the Cambridge Apostle Victor Rothschild, as Vice-Chairman of Shell Research in the 1960s, presided over the corporate lab environment where James Lovelock first developed the Gaia hypothesis. This conception of Earth as a single, self-regulating organism has since evolved from a scientific theory into a cornerstone of modern planetary governance.

The legacy is direct: the hypothesis now lends its name to the Bank for International Settlements’ own ‘Project Gaia’, a system for automated climate risk analysis14.

In 1977, Edmond de Rothschild addressed the first World Wilderness Congress, arguing for the integration of economics and banking into the conservation agenda. This proposal set in motion a process that would lead, a decade later, to the 1987 proposal for a World Conservation Bank. That concept would evolve into the Global Environment Facility, established in 1991 — the financial backbone of the UNFCCC and Convention on Biological Diversity which now structures blended finance deals, which commonly transfer management of ecosystems from indebted nations to international organisations.

Parallel to this, Evelyn de Rothschild helped develop the Interfaith Declaration on Business Ethics, crafting a moral framework alongside figures like the Duke of Edinburgh. Following the Enron collapse, the principles of this declaration were widely embedded into corporate social responsibility codes around the world.

Meanwhile, Emma Rothschild served on Ted Turner’s UN Foundation board during the period when the stakeholder model was being institutionalised, overseeing the shift from shareholder to stakeholder capitalism first trialled via the ‘World Commission on Dams’ which creates governance structures where all affected parties have voice while no one retains a deciding vote.

Jacob Rothschild, through the Rothschild Foundation, directly funded the intellectual core: the Oxford partnership and the formative Waddesdon Manor forums that crystallised the stranded assets theory.

Separately, Lynn Forester de Rothschild mobilised capital through the Coalition for Inclusive Capitalism, convening executives who controlled over $30 trillion in assets to develop the standardised ESG metrics that now govern investment.

Meanwhile, David de Rothschild shapes the narrative itself, promoting the ‘Spaceship Earth’ metaphor and carrying the systems theory language of thinkers like Kenneth Boulding into mainstream environmental advocacy15.

These were not scattered interests. They were ten distinct tracks, pursued by the same family across more than a century, all converging to build a single, coherent system.

The Ideological Lineage

The intellectual architecture being finalised today reaches back to the 1840s. In 1845, the philosopher Moses Hess described money as ‘the social blood’ — the vital circulatory system that allows society to function as a single, integrated organism.

For Hess, this was supposedly meant as a critique. He saw money as an alienating force, turning human creativity into commodity and severing people from the value of their own work. His proposed solution was to abolish money entirely.

Yet a critique can become a blueprint. To dismantle a system, you must first understand it — and in doing so, you provide a map for anyone who wants to rebuild it. Hess mapped how money integrates society, coordinates behavior, and makes individuals dependent on the whole. Those who wished to construct rather than destroy could read his work as an instruction manual.

Karl Marx then drew out the institutional implications. The fifth plank of the Communist Manifesto called for the ‘centralisation of credit in the hands of the state, by means of a national bank with state capital and an exclusive monopoly’. This wasn’t pure theory; the Bank Charter Act of 1844 was already consolidating currency under the Bank of England. Marx was describing an architecture already under construction.

Lenin made the vision operational. His concept of ‘universal accounting and control’ envisioned managing society through total surveillance of production and distribution — every transaction recorded, every resource flow monitored, every allocation planned. He defined socialism as ‘merely state-capitalist monopoly which is made to serve the interests of the whole people’.

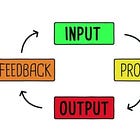

Finally, Alexander Bogdanov systematised the approach through tektology, a ‘universal science of organisation’. In his view, all systems — biological, social, or technical — function by the same principles. Society becomes another organism to be managed through measurement, feedback, and coordination.

The critique of the machine had become an engineering schematic.

Wassily Leontief made the economy’s inner flows visible. His input-output analysis, which won the Nobel Prize in 1973, tracked every material and financial movement through a society, rendering the metabolism of the social organism into spreadsheets. This became the bedrock of national accounting worldwide.

Kenneth Boulding then expanded the frame to a planetary scale. His 1966 essay, ‘The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth’, presented the planet as a closed system — a vessel with measurable inputs and exhausts. Such a system isn’t just observed; it can be modeled, monitored, and managed through feedback.

Today, that logic is reaching its operational form. The Bank for International Settlements is building what it terms the Unified Ledger: a programmable platform designed to merge central bank reserves, commercial bank deposits, and tokenised assets (which is to say, everything, unless stopped). Here, transactions can be made ‘programmable’ — conditional on compliance with metrics for ‘planetary stewardship’ and ‘social inclusion’.

The vision has come full circle — from Hegel’s philosophical concept of organic unity to the technical specifications being drafted in Basel.

The Environmental Pretext

The environmental movement provided a powerful narrative, one that delivered three crucial things: scientific authority, a compelling moral urgency, and a problem of such global scale that it demanded global governance.

But a closer look at the timeline reveals something counterintuitive: at key moments, the policy cart came before the scientific horse. Take the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), founded in 1972 as a bridge between East and West. It published its first paper on carbon pricing in 1975. Yet the very next year, Bert Bolin — who would go on to chair the IPCC — testified before the US Congress that scientists still knew very little, if anything at all about how the climate system worked.

Meanwhile, the educational framework was being laid. UNESCO’s 1975 Belgrade Charter called for environmental education to be woven into all levels of schooling to foster a ‘global ethic’. The curriculum was being designed before the scientific textbook was fully written.

This pattern continued. The focus of the first World Climate Conference in 1979 wasn’t to settle the debate on human-caused warming. Instead, it was to start planning the future on the assumption that it was real. Guiding much of that planning was Soviet systems theorist Nikita Moiseev, whose own IIASA models had led him to conclude that accurate long-term climate prediction was impossible.

The planning proceeded anyway.

The Soviet Union’s own environmental record makes the instrumental nature of this narrative difficult to ignore. In 1963, Khrushchev classified environmental data as a state secret. The ongoing ecological catastrophe at Lake Baikal was systematically concealed through official resolutions well into 1975.

The man who oversaw this cover-up as head of the USSR’s Hydrometeorological Service was Yuri Izrael. In a striking turn, he was elected Vice-Chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 1992, a position he held for sixteen years while being praised internationally for his ‘scientific excellence’.

This context makes the 1972 US-USSR Agreement on Environmental Protection particularly revealing. It created formal cooperation between two superpowers whose actual environmental practices were worlds apart. The United States possessed satellite imagery exposing the true scale of Soviet pollution, yet the agreement moved forward regardless.

As Zbigniew Brzezinski had earlier identified, ecology served as the ‘common concern’ that could facilitate global integration. Here, the environment provided the pretext — while the construction of the international mechanism itself was always the goal. Brzezinski went on to co-found the Trilateral Commission.

The process operates like a closed circuit. Climate models function as a black box: data goes in, projections come out, and those projections are immediately translated into ‘ethical imperatives’ for action. The technical output becomes a moral obligation. Once that shift happens, questioning the model’s assumptions is no longer an empirical debate — it’s treated as moral failing.

The term ‘denier’ completes this move. It assigns a character flaw, placing the skeptic outside the bounds of reasonable conversation.

This protective shield then extends to the financial architecture built upon the science. Question the Basel Committee’s capital requirements, and you’re referred to the NGFS climate scenarios. Question the NGFS scenarios, and you’re directed back to the underlying climate science. Question the climate science, and you’re branded a denier.

It’s a perfect loop. The chain of justification ends in a model that answers to no one, is validated by its own predictions, and is effectively immune to falsification. Yet its outputs are now rewriting the rules of the global financial system.

The scientific black box establishes the moral emergency; the financial black box is the mechanism that enforces it.

Regional Branding

The core financial architecture remains the same, but its public-facing narrative shifts to match the audience.

In the United Kingdom, it was branded the ‘Big Society’ — a story of community empowerment and local solutions filling the gap left by a retreating state. Big Society Capital, launched in 2012 with £400 million from dormant bank accounts and another £200 million from major banks, became its engine. It funnels private investment into social services through outcome-based contracts, effectively replacing public provision with private finance.

In the United States, the terminology softens into the language of ‘impact investing’ — the idea of doing well by doing good. This frame of conscious capitalism and stakeholder value aligns with American optimism and Silicon Valley’s disruptor ethos. It was this model that Ronald Cohen, having established it in the UK, brought across the Atlantic through the G8 Taskforce he chaired starting in 2013.

At the United Nations level, the jargon becomes ‘blended finance’ — a technical term for mobilising private capital to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. The $100 billion annual climate finance pledged at Copenhagen in 2009 now flows through instruments like green bonds and multilateral development banks. The catch is that this capital comes with strings attached: developing nations must adopt Western ESG frameworks to qualify.

The system is universal; only its labels change.

The European Union frames it in the clinical language of ‘sustainable finance’ and ‘taxonomy’ — a science-based, technocratic vision of market efficiency. Laws like the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive and the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism hardwire compliance into the legal code, with enforcement increasingly delegated to algorithmic verification.

The Vatican, in contrast, supplies the moral vocabulary of ‘inclusive capitalism’ — markets that ethically care for creation and the poor. This framing received papal blessing in 2019 through the Council for Inclusive Capitalism, co-founded by Lynn Forester de Rothschild. Here, moral authority aligns with and reinforces regulatory power.

Despite the different branding — technocratic in Brussels, spiritual in Rome — the underlying structure is identical. Public capital de-risks private investment, socialising losses while privatising gains. Political debates are converted into technical metrics to be optimised, not discussed. Surveillance expands to feed the data needed for compliance. And ultimately, access to the financial system itself depends on adhering to the metrics.

The labels change, but the machinery does not.

The BIS Innovation Hub

The Bank for International Settlements Innovation Hub is constructing this system piece by piece. Its laboratories, scattered across financial centers from Basel to Hong Kong to Toronto, are each developing modular components. When combined, they form a complete architecture for programmable money and automated compliance.

Projects like mBridge, Dunbar, Nexus, and Icebreaker are building the rails for cross-border payments, directly linking the digital currencies of central banks across Asia and the Middle East.

Meanwhile, the compliance layer is being baked directly into the transaction process. Project Mandala embeds regulatory rules into payment flows, and Project Aurora uses AI for instantaneous AML screening. Enforcement becomes invisible and pre-emptive, stopping transactions before they happen rather than auditing them after the fact.

The critical piece is Project Rosalind, developed with the Bank of England. It creates the integration layer for a retail digital currency, implementing a ‘three-party lock’ mechanism. This allows conditions — policy rules, identity checks, or even environmental criteria — to be embedded directly into a payment. The transaction only executes if it satisfies all pre-set requirements.

This is the endpoint: programmable compliance governing every individual purchase.

Under traditional law, enforcement follows the crime: you break a rule, you face investigation, a trial, and a penalty. Programmable finance flips this logic on its head. It operates through prevention — transactions that don’t meet the rules are simply blocked from ever happening. There’s no violation to prosecute because non-compliance is filtered out at the source.

This is the architecture now being assembled. Project Helvetia integrates a wholesale digital currency with securities settlement. Project Mariana experiments with decentralised finance protocols for central bank money. Project Genesis tokenises green bonds, wiring climate finance directly into the payment layer.

All of these components converge in what the BIS calls the Unified Ledger — a single programmable platform where every transaction must pass through checkpoints defined by the official taxonomy. What counts as ‘green’, what qualifies as ‘inclusive’, what meets the criteria for system access — these aren’t just guidelines. They become hard-coded gates in the financial infrastructure itself.

The Basel Enforcement Mechanism

The final piece is enforcement, and it arrives through Basel 3.1 — the updated banking regulations set to take effect in January 2027.

Here’s how it works: banks must hold capital as a buffer against potential losses. The riskier the asset, the more capital they need to set aside. Under the new rules, the Basel Committee assigns standardised risk weights through a simple lookup table. A loan to a renewable project gets one weight; a loan to a fossil fuel company gets a much heavier one. That number directly determines how expensive it is for a bank to keep that asset on its books.

Banks already report their holdings in extreme detail through regulatory filings. Supervisors know exactly who holds what. So when the Committee raises the risk weight for a specific asset class — say, coal infrastructure — every bank exposed to it suddenly needs to find more capital. The adjustment appears neutral, but its impact is highly targeted: a bank with heavy exposure is squeezed, while competitors are left untouched.

The affected bank is then forced into a corner. It must raise expensive new capital, sell assets quickly (often at a loss), or shrink its lending. No public announcement targets a specific industry. No parliamentary vote is held. It’s just a technical update to a spreadsheet in Switzerland.

This is the mechanism that actually strands assets. Climate risk models generate scores; those scores feed into the Basel risk-weight table; the table dictates capital requirements; and those requirements determine whether financing flows or stops. The taxonomy developed years ago at Waddesdon Manor becomes enforceable policy through Basel. The data supplied by monitoring systems like Climate TRACE provides the justification. And a committee meeting in Switzerland quietly sets the weights that determine which industries survive.

The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

The system operates in a closed loop: it creates the very conditions it claims only to predict. Regulators label certain assets as climate risks, leading to higher capital requirements, reduced lending, and investor retreat. This triggers underinvestment, which causes supply constraints and price volatility — thereby appearing to confirm the original risk assessment.

The prophecy fulfills itself.

The process follows a clear chain. First, satellite systems like Climate TRACE generate asset-level emissions data, using AI to estimate — or effectively fabricate16 — figures for facilities that don’t report. This data feeds into climate risk models that produce risk scores. Those scores then populate the Basel Committee’s risk-weight tables.

Higher risk weights mean higher capital costs for banks. When lending becomes too expensive, credit dries up. Loan covenants are triggered, insurance coverage may void, and capital fleets. The asset is stranded not because the underlying resource lost value, but because the financial system withdrew its lifeline.

This bypass was intentional. With carbon taxes repeatedly rejected at the ballot box, the stranded assets framework offered what participants called a ‘second-best’ solution: reallocating capital through financial regulation instead of legislation. Voters never approve the taxonomy, never elect the modelers — the capital simply moves according to rules they had no say in creating.

The scope is widening. Research has already mapped over 100,000 farms globally for potential ‘stranding’ based on emissions and water use17. Debt-for-nature swaps and sovereign sustainability metrics are extending the architecture from energy to agriculture, land ownership, and national fiscal policy.

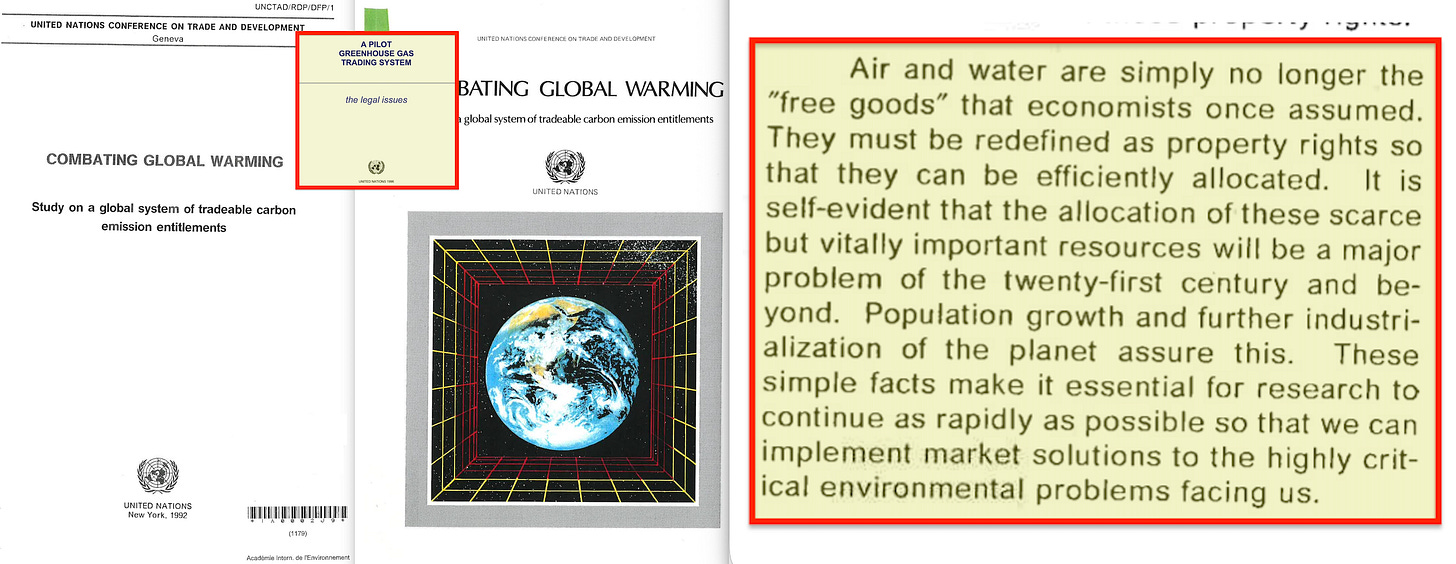

On the other side of the mechanism sits revenue extraction through carbon credits and ecosystem services. The blueprint dates to 1992, when a UNCTAD study co-authored by Michael Grubb and Richard Sandor plainly stated the goal: air and water must be ‘redefined as property rights so that they can be efficiently allocated’.

What was declared a commons must become a commodity — managed, measured, and traded within the very system that declared the crisis.

The mechanism operates on two fronts, each reinforcing the other. First, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change creates artificial scarcity by placing a cap on allowable emissions. Then, the Convention on Biological Diversity expands the supply of carbon sinks — through restored forests and wetlands — that can offset that scarcity.

This is where finance takes over. The Global Environment Facility structures blended deals where public funds absorb the risk, private investors take the senior position, and the resulting ‘ecosystem services’ are packaged into assets. These can be held by corporations and even floated on stock exchanges in the form of Natural Asset Companies. Much of the inventory comes from the same forests designated under UNESCO’s Biosphere Reserve programme — an area comparable in size to Australia — transforming preserved land into a monetisable ledger entry.

So one part of the architecture withdraws capital from emitters, while the other extracts rent from them. They appear to be separate instruments, but both are engineered to move toward the same end.

Conclusion

What is being built today is the technical fulfillment of a vision outlined almost two hundred years ago. Moses Hess saw money as the integrating force of social life — control its circulation, and you control the organism. Marx identified the institutional lever, Lenin operationalised total surveillance, Bogdanov created a universal science of organisation, Leontief made economic flows calculable, and Boulding scaled the logic to a planetary system.

The environmental narrative was merely the latest vehicle. Global crises demand global governance; scientific complexity calls for technocratic management; moral urgency overrides democratic hesitation. In this frame, the planet becomes a patient, and the specialists who treat it cannot be questioned.

In the end, whether climate change poses the specific risks assigned to it is almost beside the point. The architecture would have been built regardless. The stranded assets framework, the impact investing infrastructure, blended finance, central bank coordination, and programmable money all serve the same function — whatever the validity of their environmental justification.

The system that labels an investment ‘impactful’ is the same system that labels an asset ‘stranded’. The taxonomy that attracts capital is the taxonomy that withholds it. The machinery is singular. Only the direction of the current changes.

The entire apparatus will soon function as a seamless, automated whole. The frameworks developed in closed-door forums, the scenario models synchronised across central banks, the technical components built in innovation labs — all converge in the Unified Ledger, forming a single, integrated operating system for global finance.

Only the interface changes by region. In London, it’s branded as the Big Society; in New York, as impact investing; in Geneva, as blended finance; in Brussels, as sustainable taxonomy; in Rome, as inclusive capitalism. The language is localised, but the underlying code is identical. State authority does not disappear here — it becomes the ledger itself. Power is embedded within infrastructure, automated and invisible, dressed as mere technological advancement, much like Marx’s Fragment on Machines predicted it would.

The mechanism is self-justifying. Label an asset a climate risk, withdraw capital, observe its decline, and then point to that failure as proof of the original risk. Expand the classification; next follows agriculture, power plants, factories, even homes built in ‘endangered ecosystems’ per the IUCN or ‘potential future flood plains’ assuming a 2 degree rise in temperatures.

No conspiracy is required — the incentives are aligned, the metrics are standardised, and the exits are systematically closed. Should the label ‘stranded asset’ be associated with your home, you can forget about selling or insuring it. The mechanism is general purpose, and almost impossible to audit or appeal.

In the end, the global financial system is being fundamentally reorganised according to the outputs of a ‘black box’ model that answers to no one, is validated by its own predictions, and is shielded from all challenge. This isn’t even speculative; when a pivotal paper was recently retracted, the NGFS Scenarios it led to were not. Capital is currently priced on the basis of a model which they know is flawed.

The only institutional response has been to outsource future scenarios to a new Scientific Advisory Committee — a body about which almost nothing is publicly known, and an ideal refuge for the self-proclaimed Navigators of Spaceship Earth.

The future is not just predicted but prescribed, one transaction at a time. Moses Hess, writing in 1845, let us in on the objective:

Selfishness is the disease. Integration is the cure. Money is the medium through which the cure is administered.

And the transaction that does not meet the criteria — whether in London, New York, or Nairobi — simply does not occur, because the CBDC won’t allow it.

Find me on Telegram: https://t.me/escapekey

Find me on Gettr: https://gettr.com/user/escapekey

Bitcoin 33ZTTSBND1Pv3YCFUk2NpkCEQmNFopxj5C

Ethereum 0x1fe599E8b580bab6DDD9Fa502CcE3330d033c63c

Methinks this might be starting to unravel. The impetus for the unraveling is when the foundations of the system begin to crack, leading eventually to a phenomenon much seen in history called “every man for himself”. When this final stage begins there is no stopping the disintegration. The global financial architecture so well described here is tottering. We saw the “sway” on Friday with the coordinated massive sell off of gold, silver and precious metals, all now a serious threat to fiat systems, especially the USD, and the pointed destruction of the middle class and subjugation of the masses.

There is an old saying in aviation that says, “no matter what happens, fly the airplane”. That works unless the wings fall off.